Abstract

The formation of annular abscess and fistulous communication, the most devastating complication of destructive aortic valve endocarditis, requires extensive surgical débridement.

Five men experienced destructive native aortic valve endocarditis in association with congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association functional class IV) and hemodynamic deterioration that developed from severe aortic regurgitation. To eradicate the aortic valve endocarditis, we performed (from July 1998 through November 2002) aortic annular skeletonization by dissecting all infectious and necrotic tissue within the abscess cavity and the fistula between the ventriculoarterial junction and the sinotubular junction. The completely resected annular area was covered with a glutaraldehyde-treated autologous pericardial patch that was sutured firmly to fibrous tissue, for a secure proximal anastomosis. Reconstruction of the aortic root was followed by implantation of a Freestyle® stentless bioprosthesis, using the aortic root replacement technique.

There were no deaths after surgery, nor is there record of a permanent complication due to a loss of conduction tissue. All 5 patients were in New York Heart Association functional class I or II during follow-up (range, 8–56 months). Echocardiography showed no signs of valve dysfunction, recurrent endocarditis, or fistulation.

Annular skeletonization and reconstruction of the aortic annulus with glutaraldehyde-treated autologous pericardium permits radical removal of infected tissue and effective treatment of aortic annular abscess, with less risk of valve dehiscence from the fragile aortic annulus.

Key words: Aortic diseases/surgery; endocarditis, bacterial/surgery; bioprosthesis; debridement; pericardium/transplantation; retrospective studies

The formation of annular abscess and fistulous communication is the most devastating complication of destructive aortic valve endocarditis (AVE) and requires extensive surgical débridement.1,2 Patients with destructive AVE have more prolonged fever before diagnosis and longer persistence of the fever after initiation of therapy, together with significantly higher rates of embolic events and death, and greater need of surgical re-intervention.2 Once an aortic root abscess is detected, urgent surgery is required, because antibiotics alone will fail to control the infection, and surgery is usually curative. Débridement of all infected and necrotic tissue is the mainstay of the surgical treatment of aortic root abscess. Varying degrees of annular involvement present a substantial challenge in restoring the anatomic and functional integrity of the cardiac structures after removal of infected tissue. Several different surgical techniques have been advocated, including closure of the defect with a patch,3 aggressive débridement of the abscess and surrounding tissue accompanied by reconstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract with autologous or bovine pericardium,1,4 translocation of the aortic valve,5 and extra-anatomic bypass of the aortic root.6

We present the results of our retrospective study of radical débridement using annular skeletonization with resection of all infectious and necrotic tissue regardless of the cardiac structures involved, followed by restoration of aortic continuity using a glutaraldehyde-treated autologous pericardial patch.

Patients and Methods

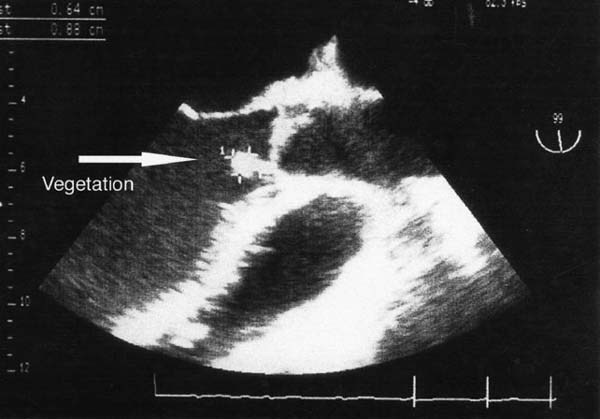

From July 1998 through November 2002, 5 men between the ages of 29 and 51 years (mean, 42.4 ± 8.7 years) with destructive native AVE were admitted to our institution with congestive heart failure and hemodynamic deterioration as a consequence of severe aortic regurgitation. All 5 patients were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class IV. The diagnosis of AVE was made on the basis of physical examination, laboratory findings, blood cultures, and transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography. All patients had fevers greater than 38 °C. Conduction anomalies were not detected. Echocardiographic examination revealed valvular vegetation, annular abscess, fistula, and enlargement of the aortic root in all patients (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Transthoracic echocardiogram shows the long-axis view of the left ventricle and aortic outflow tract. The arrow points to the vegetation arising from the aortic root abscess at the base of the interventricular septum.

The preoperative aortic valve conditions were determined to be rheumatic calcification (3 patients), congenital bicuspid aortic stenosis (1 patient), and congenital calcified bicuspid aortic stenosis (1 patient), complicated in all cases by poststenotic dilatation or aneurysm of the ascending aorta that required root replacement. All patients had received antibiotic therapy before surgery for a period ranging between 6 and 14 days (Table I).

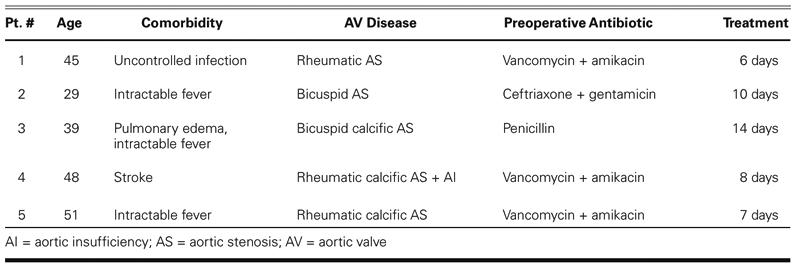

TABLE I. Preoperative Data on Patients

Surgical Technique

All patients underwent moderate (28 °C) hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass by means of bicaval cannulation with cannulation of either the ascending aorta (4 patients) or the femoral artery (1 patient). The left ventricle was vented through the right superior pulmonary vein. Isothermic blood cardioplegic solution was administered retrograde during aortic cross-clamping.

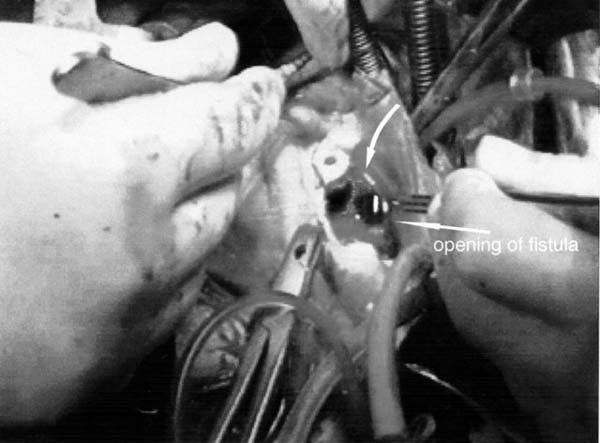

All patients presented with acute necrotizing endocarditis with valvular vegetation, destruction of the annulus, and annular abscess. All patients had fistulae entering the cardiac chambers (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 The tract of the fistula extends from the right atrium to the noncoronary sinus. The arrows point to the tract (top) and to the opening of the fistula.

For eradication of the AVE, aortic annular skeletonization was performed by resecting all infected and necrotic tissue around the annulus and within the abscess and fistula between the ventriculoarterial junction and the sinotubular junction. All vegetations were removed; in Patient 1, an additional vegetation, 0.5-cm in diameter, was resected from the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve.

Approaches to the fistulae were via a right atriotomy or (in Patient 3) a combined transseptal–superior left atriotomy. The aortotomy incision was extended to the noncoronary commissure, then this line was extended again until it met the left atrial incision line. These combined incisions enabled us to resect the whole abscess with its fistulous communication and to close the tract of the fistula from both sides with pericardial pledgeted sutures.

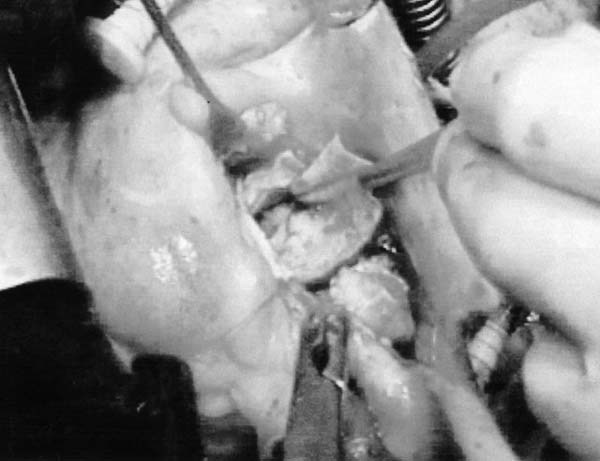

Before cardiopulmonary bypass, a patch was harvested from the pericardium, stabilized with 0.62% glutaraldehyde solution for 5 minutes, and rinsed thoroughly with 0.9% saline solution. The pericardial strip, trimmed to a length of 1.5 cm, was sutured continuously with 5-0 polypropylene, beginning either at the level of the base of the sinus of Valsalva (ventriculoarterial junction) or at the commissural level of the annulus (sinotubular junction) (Fig. 3). The completely resected annular area was covered with the glutaraldehyde-treated autologous pericardial patch sutured to firm, fibrous tissue for a secure proximal anastomosis. The interior aortic wall, including the interleaflet triangles, was covered with glutaraldehyde-treated pericardium, effectively excluding from the circulation all aortic abscess cavities and fistulous communications.

Fig. 3 Reconstruction of the aortic annulus with glutaraldehyde-treated autologous pericardium.

Reconstruction of the aortic root was followed by implantation of a Freestyle® stentless aortic bioprosthesis (Medtronic, Inc.; Minneapolis, Minn) in the left ventricular outflow tract; the repaired annulus was attached tightly to the pericardial cuff with 3-0 polypropylene running suture. In all patients, reimplantation of the coronary ostia was performed by means of the button technique, with 5-0 polypropylene suture. The distal anastomosis between the xenograft and the ascending aorta was performed with 4-0 polypropylene running suture.

The mean perfusion time was 338 min (range, 214–440 min), and the mean aortic cross-clamping time was 164 min (range, 146–225 min).

Results

There was no early or late mortality. Two of the 5 patients needed to be weaned from cardiopulmonary bypass with intra-aortic balloon pump support. None required reoperation for bleeding. Two patients needed temporary pacing, for 6 and 15 days. There is no record of a permanent complication in these patients due to conduction tissue injury.

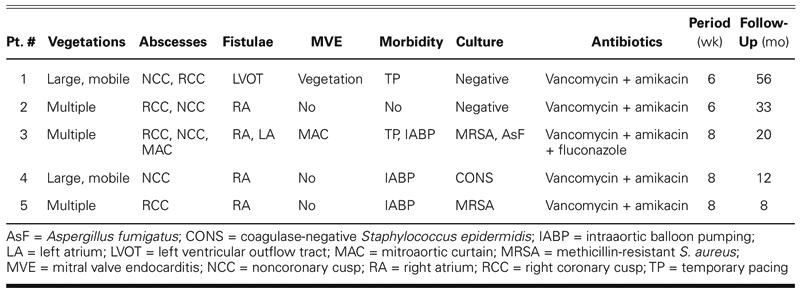

Specimens taken from resected tissue revealed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in 1 patient and coagulase-negative S. epidermidis in 2 patients. Aspergillus fumigatus was found on aortic valve tissue in 1 patient. (One of these patients had multiple pathogens.) Tissue cultures from the remaining 2 patients were negative due to the antibiotic therapy given empirically at the onset of fever before blood cultures were obtained. Intravenous combined antibiotic therapy was continued for 6 or 8 weeks postoperatively in all patients, in accordance with their antibiograms (Table II).

TABLE II. Operative and Postoperative Data on Patients

At follow-up 8 to 56 months (mean, 25.8 months) after surgery, 3 patients were in New York Heart Association functional class I, and 2 patients were in NYHA functional class II. Echocardiography showed no signs of valve dysfunction, recurrent endocarditis, or fistulation.

Discussion

Aortic valve endocarditis with destruction of the aortic annulus and abscess formation is a grave condition, and an aggressive combined surgical and medical approach is essential for effective treatment.1,2,7,8 Intracardiac fistulization, hemodynamic deterioration due to severe aortic regurgitation, and the high risk of cerebral embolization are conditions that usually need urgent surgical intervention.1 Due to the patients' preoperative conditions as a result of sepsis, treatment of complex AVE is a surgical challenge, with a reported mortality rate that ranges from 9% to 23%.9 Early aggressive surgical therapy is more successful than delayed surgery in treating active infective aortic root endocarditis with periannular abscesses.7,8

Annular abscesses or intracardiac fistulae increase the technical difficulties and risks associated with surgical treatment.7,10,11 To minimize the risk of recurrent endocarditis, and thereby improve late survival, complete débridement of all infected tissue is mandatory. A curative result can be achieved only by means of a very radical surgical approach, which results in extensive defects of the aortic annulus and the left ventricular outflow tract.1,8 Adequate débridement also causes difficulty in securely affixing rigid or stented replacement prostheses, which can result in recurrent endocarditis or valve dehiscence.

The use of biological prosthetic material has clear advantages. Bioprotheses have displayed the lowest levels of recurrent infection. The aortic homograft has been used for endocarditis because of its several advantages, including excellent hemodynamic performance and resistance to reinfection;7,8 but homografts are in short supply, so alternative conduits are needed. Stentless conduits provide an alternative when no suitable homograft is available.12,13

Stentless porcine aortic valves have a design similar to that of an aortic homograft and use a minimum of nonbiologic material. The Freestyle bioprosthesis offers several advantages over traditional prostheses.14,15 Among these are superior hemodynamics, laminar flow patterns, lack of need for anticoagulation, and perhaps improved durability. At 8 years, freedom from thromboembolic complications was reported to be 83.3%, freedom from postoperative endocardi-tis was 96.9%, and freedom from reoperation was 100%.15 The Freestyle bioprosthesis can be inserted alone in the subcoronary position in patients with an infected aortic annulus, but total root replacement may be needed when the root abscess is at the level of the annulus or above.

There have been recent reports9,13 of successful treatment of destructive aortic valve endocarditis with the Freestyle stentless bioprosthesis, as a substitute for the aortic homograft. According to Müller and colleagues,9 among 10 consecutive patients with extensive abscess formation who underwent Freestyle aortic root xenograft implantation, 1 had a preoperative septic ventricular septal defect and fistula into the right atrium, with tricuspid valve endocarditis. Müller stressed that 7 patients in the series were observed to have no signs of valve dysfunction, recurrent fistulation, or endocarditis. Fukui and colleagues13 reported that 5 patients with complex aortic root infection underwent aortic root replacement with Freestyle stentless bioprostheses, without early or late death or evidence of recurrent endocarditis.

In using the Freestyle bioprosthesis for AVE, we believe that the fabric covering the ventricular site might possibly act as a nidus for recurrent infection. Therefore, we prefer to cover the annulus with an autologous pericardial patch anchored within the left ventricular outflow tract; this enables broad and secure attachment of the sewing cuff of the bioprosthesis, in order to avoid paravalvular leakage and to provide a barrier against recurrent infection. The glutaraldehyde-treated autologous pericardial patch molds well to the fragile infected aortic annulus and reduces the risk of valve dehiscence from the annulus.

In conclusion, reconstruction of the aortic annulus with pericardium in destructive AVE makes possible adequate débridement of all infected tissue and enables secure placement of the bioprosthesis.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Dr. Nilgun Bozbuga, Kosuyolu Heart and Research Hospital, Kosuyolu, 81020 Istanbul, Turkey

E-mail: nbozbuga@kosuyolu.gov.tr

References

- 1.d'Udekem Y, David TE, Feindel CM, Armstrong S, Sun Z. Long-term results of operation for paravalvular abscess. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;62:48–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Knosalla C, Weng Y, Yankah AC, Siniawski H, Hofmeister J, Hammerschmidt R, et al. Surgical treatment of active infective aortic valve endocarditis with associated periannular abscess—11 year results. Eur Heart J 2000;21:490–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Fiore AC, Ivey TD, McKeown PP, Misbach GA, Allen MD, Dillard DH. Patch closure of aortic annulus mycotic aneurysms. Ann Thorac Surg 1986;42:372–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.David TE, Komeda M, Brofman PR. Surgical treatment of aortic root abscess. Circulation 1989;80(3 Pt 1):I269–74. [PubMed]

- 5.Endo M, Nishida H, Imamura E, Koyanagi H. Sutureless aortic valve replacement for periannular abscess due to active bacterial endocarditis: a new translocation technique. Ann Thorac Surg 1988;45:568–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Bove EL, Parker FB Jr, Marvasti MA, Randall PA. Complete extra-anatomic bypass of the aortic root: treatment of recurrent mediastinal infection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1983;86:932–4. [PubMed]

- 7.Yankah AC, Klose H, Petzina R, Musci M, Siniawski H, Hetzer R. Surgical management of acute aortic root endocarditis with viable homograft: 13-year experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002;21:260–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Niwaya K, Knott-Craig CJ, Santangelo K, Lane MM, Chandrasekaran K, Elkins RC. Advantage of autograft and homograft valve replacement for complex aortic valve endocarditis. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67:1603–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Muller LC, Chevtchik O, Bonatti JO, Muller S, Fille M, Laufer G. Treatment of destructive aortic valve endocarditis with the Freestyle Aortic Root Bioprosthesis. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:453–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Aagaard J, Andersen PV. Acute endocarditis treated with radical debridement and implantation of mechanical or stented bioprosthetic devices. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;71:100–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kameyama T, Ando F, Okamoto F, Hanada M, Sasahashi N. A brimmed valved conduit in repair of fibrous skeleton abscess. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;66:2108–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Siniawski H, Lehmkuhl H, Weng Y, Pasic M, Yankah C, Hoffmann M, et al. Stentless aortic valves as an alternative to homografts for valve replacement in active infective endocarditis complicated by ring abscess. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:803–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Fukui T, Suehiro S, Shibata T, Hattori K, Hirai H, Aoyama T. Aortic root replacement with Freestyle stentless valve for complex aortic root infection. J Thorac and Cardiovasc Surg 2003;125:200–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Bach DS, Cartier PC, Kon ND, Johnson KG, Deeb GM, Doty DB; Freestyle Valve Study Group. Impact of implant technique following Freestyle stentless aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;74:1107–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Kon ND, Riley RD, Adair SM, Kitzman DW, Cordell AR. Eight-year results of aortic root replacement with the Freestyle stentless porcine aortic root bioprosthesis. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;73:1817–21. [DOI] [PubMed]