Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS) affects 40% of patients following spine surgery with estimated costs of $20 billion to the US health care system. The aim of this study was to assess the cost differences across the different insurance providers for FBSS patients.

METHODS

A retrospective longitudinal study was performed using the Truven MarketScan® database to identify FBSS patients from 2001 to 2012. Patients were grouped into Commercial, Medicaid, or Medicare cohorts. We collected 1-year prior to FBSS diagnosis (baseline), then at year of SCS-implantation and 9-year post-SCS implantation cost outcomes.

RESULTS

We identified 122,827 FBSS patients, with 117,499 patients who did not undergo an SCS-implantation (Commercial: n=49,075, Medicaid: n=23,180, Medicare: n=45,244) and 5,328 who did undergo an SCS implantation (Commercial: n=2,279, Medicaid: n=1,003, Medicare: n=2,046). Baseline characteristics were similar between the cohorts, with the Medicare-cohort being significantly older. Over the study period, there were significant differences in overall cost metrics between the cohorts who did not undergo SCS implantation with the Medicaid-cohort had the lowest annual median [IQR] total cost (Medicaid: $4530.4 [$1,440.6, $11,973.5], Medicare: $7292.0 [$3,371.4, $13,989.4], Commercial: $4944.3 [$363.8, $13,294.0], p<0.0001). However, when comparing the patients who underwent SCS implantation, the Commercial-cohort had the lowest annual median [IQR] total costs (Medicaid: $4,045.6 [$1,146.9, $11,533.9], Medicare: $7,158.1 [$3,160.4, $13,916.6], Commercial: $2,098.1 [$0.0, $8,919.6], p<0.0001).

CONCLUSIONS

Our study demonstrates a significant difference in overall costs between various insurance providers in the management of FBSS, with Medicaid-insured patients having lower overall costs compared to Commercial- and Medicare-patients. SCS is cost-effective across all insurance groups (Commercial > Medicaid > Medicare) beginning at 2 years and continuing through 9-year follow-up. Further studies are necessary to understand the cost differences between these insurance providers, in hopes of reducing unnecessary health care expenditures for patients with FBSS.

Keywords: Insurance Disparities, FBSS, SCS, Medicare, Medicaid, Cost

INTRODUCTION

Chronic low back pain (cLBP) is rising as one of the most expensive conditions to manage, with approximately 37% of adults affected and annual costs ranging from 12.2–90.6 billion health care dollars.1–3 It is estimated that 10–40% of patients have persisting pain after surgical treatment for cLBP and are diagnosed with Failed Back Surgery Syndrome (FBSS), with estimated health care costs of up to $20 billion dollars annually.1–4 First line therapy for patients with FBSS is conventional medical management (CMM), followed by spinal cord stimulation (SCS) in select patients where CMM has failed and re-operation is undesirable.5–7 While there are studies comparing the outcome and cost differences between CMM and SCS, efforts in identifying other factors that may lessen the burden of the soaring healthcare costs are necessary.8,9

In particular, a disparity in insurance providers is one contributing factor that is readily marginalized. Recently, insurance claims and hospital reimbursements have increasingly become more complex and have profound effects on healthcare management and overall costs in treatment plans. Prior studies have found differences between healthcare utilization and insurance providers in patients with FBSS. Important to note, Medicare is predominantly for elderly patients 65 years and older, while Medicaid is for low-income families or individuals of any age. In a retrospective analysis of 16,455 patients with FBSS, Lad et al. found that Commercial- and Medicare-insured patients were more likely to undergo lumbar reoperation, with significantly more Medicaid patients undergoing SCS implantation.10 However, the effect of different insurance providers on overall costs in managing patients with FBSS is relatively unknown.

The aim of this study was to assess the cost differences for patients undergoing SCS implantation as well as those who did not, across different insurance providers for patients with FBSS.

METHODS

Patients were retrospectively queried from the Truven Reuters MarketScan® database to identify patients with a history of FBSS from 2001 to 2012. The MarketScan database consists of patient-specific data on clinical utilization, including inpatient, outpatient, medication, and laboratory information from insurance enrollment and costs. Patients were grouped into Commercial, Medicaid, or Medicare cohorts based on the patients’ insurance claims.

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, [ICD-9] codes were used to select patients with a diagnosis of FBSS. The following codes were used: 72283, 3382, and 3384. FBSS patients were defined as having the ICD code 77283, or a chronic pain diagnosis code of 3382 or 3384 with a prior lumbar spine surgery procedure code of 63005, 63012, 63017, 63030, 63042, or 63047. Patients with a history of SCS were defined by the presence of the procedure code 63685 and one of the following codes: 63650 or 63655. Only patients with a minimum of one year of continuous data were included.

Baseline characteristics were collected for all patients including patient age, gender, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), and date of claim. Cost data were collected for all patients one year prior to the first diagnosis of FBSS, as well as annual costs following the initial diagnosis. Descriptive statistics were reported at the time of SCS implantation, and post-implantation for the SCS patients, as well as for the non-SCS implanted patients. Negative and extremely large values were removed by excluding the highest and lowest 1% of values to account for outliers. The data included total costs of all medical expenses, pain-related procedure costs, pain prescription costs, medication costs, number of pain-related encounters, and number of pain prescriptions.

A longitudinal analysis was used to model the value of log(cost) in each one year interval using a generalized estimating equations (GEE) linear regression model to account for the correlation of the same patient’s cost in multiple years. Each model includes sex, age, charlson score, insurance, an indicator of received SCS this year, an interaction between indicator of received SCS this year and the normalized surgery calendar year, an interaction between indicator of received SCS this year and insurance, an interaction between indicator of post-SCS and post-SCS years, an interaction between indicator of post-SCS year, post-SCS years and insurance. All the GEE models assumed an exchangeable correlation structure for patients with multiple years of data. All analyses and data processing were conducted using SAS software, V9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.

RESULTS

We identified 122,827 FBSS patients (Commercial: n=51,354, Medicaid: n=24,183, Medicare: n=47,290) with 117,499 patients who did not have SCS-implantation (Commercial: n=49,075, Medicaid: n=23,180, Medicare: n=45,244) and 5,328 who had an SCS-implantation (Commercial: n=2,279, Medicaid: n=1,003, Medicare: n=2,046). Baseline characteristics were different amongst the cohorts, with the Medicare patient population being older in age and having higher median CCI score than the other cohorts (Commercial: 1.0 vs. Medicaid: 1.0 vs. Medicare: 2.0, p<0.0001), Table 1. There were more females than males in each of the cohort (Commercial: 54.8%, Medicaid: 65.5%, Medicare: 55.9%) and the year 2009 had the highest number of insurance claims than the other years (44.1%), Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Years of Claims

| Variable | Commercial (51,354) | Medicare (47,290) | Medicaid (24,183) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCS Implantation n(%) | ||||

| No SCS SCS |

49075 (95.6%) | 45244 (95.7%) | 23180 (95.9%) | 0.1862 |

| 2279 (4.4%) | 2046 (4.3%) | 1003 (4.1%) | ||

| Gender n(%) | ||||

| Male Female |

23235 (45.2%) | 20849 (44.1%) | 8332 (34.5%) | <0.0001* |

| 28119 (54.8%) | 26441 (55.9%) | 15851 (65.5%) | ||

| Age Median[IQR] | 51.0 [44.0, 57.0] | 72.0 [67.0, 78.0] | 50.0 [42.0, 59.0] | <0.0001* |

| CCI | 1.0 [0.0, 1.0] | 2.0 [1.0,3.0] | 1.0 [1.0,3.0] | <0.0001* |

| Year of Claim n(%) | ||||

| 2001 | 836 (1.6%) | 667 (1.4%) | 806 (3.3%) | <0.0001* |

| 2002 | 1409 (2.7%) | 1695 (3.6%) | 993 (4.1%) | |

| 2003 | 2250 (4.4%) | 3333 (7.0%) | 2293 (9.5%) | |

| 2004 | 3491 (6.8%) | 3333 (7.0%) | 2293 (9.5%) | |

| 2005 | 5016 (9.8%) | 4379 (9.3%) | 2387 (9.9%) | |

| 2006 | 5073 (9.9%) | 3927 (8.3%) | 2210 (9.1%) | |

| 2007 | 7523 (14.6%) | 4415 (9.3%) | 1512 (6.3%) | |

| 2008 | 8479 (16.5%) | 4473 (9.5%) | 1629 (6.7%) | |

| 2009 | 11986 (23.3%) | 5519 (11.7%) | 2202 (9.1%) | |

| 2010 | 3149 (6.1%) | 3750 (7.9%) | 1890 (7.8%) | |

| 2011 | 952 (1.9%) | 5714 (12.1%) | 3132 (13.0%) | |

| 2012 | 1190 (2.3%) | 7075 (15.0%) | 3154 (13.0%) | |

Cost at Baseline, 1-Year Prior to FBSS Diagnosis

At baseline, there were significant differences in overall cost metrics between the cohorts. Compared to the Commercial and Medicare cohorts, the Medicaid-cohort had the lowest median [IQR]: (1) total costs (Medicaid: $5,464.3 [$2,045.1, $12,434.4], Medicare: $8,262.7 [$4,083.8, $15,035.9], Commercial: $10,072.8 [$4,347.8, 19,260.08], p<0.0001); and (2) cost of medications (Medicaid: $1555.5 [$115.6, $4762.6], Medicare: $3189.3 [$1529.2, $5428.0], Commercial: $1884.7 [$550.0, 4217.9], p<0.0001) Table 2.

Table 2.

Cost at Baseline, 1-Year Prior to Diagnosis of FBSS

| Variable – Median[IQR] Mean (SD) | Commercial | Medicare | Medicaid | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cost | 10072.8 [4347.8, 19260.0] | 8262.7 [4083.8, 15035.9] | 5464.3 [2045.1, 12434.4] | <0.0001* |

| 14371.0 (15624.9) | 11742.2 (12634.6) | 9453.3 (14252.7) | ||

| Pain Prescriptions Costs | 251.9 [45.7, 893.9] | 207.6 [35.1, 775.4] | 238.8 [7.7, 956.0] | <0.0001* |

| 794.8 (1402.8) | 615.2 (1060.6) | 852.0 (1550.5) | ||

| Medication Costs | 1884.7 [550.0, 4217.9] | 3189.3 [1529.2, 5428.0] | 1555.5 [115.6, 4762.6] | <0.0001* |

| 2964.1 (3341.6) | 3863.6 (3173.0) | 3145.6 (4067.9) | ||

| Number of Pain Prescriptions | 10.0 [4.0, 22.0] | 7.0 [3.0, 14.0] | 17.0 [4.0, 29.0] | <0.0001* |

| 14.5 (14.2) | 9.8 (9.8) | 19.4 (17.9) |

Medicare patients had lower number of pain prescriptions (Medicaid: 17.0 [0.0, 30.0], Medicare: 7.0 [5.0, 19.0], Commercial: 10.0 [8.0, 29.0], p<0.0001), and lower median pain prescription cost (Medicaid: $238.8 [$7.7, 956.0], Medicare: $207.6 [$35.1, 775.4], Commercial: $251.9 [$45.7, $893.9], p<0.0001), compared to the other insured cohorts, Table 2.

Annual Cost for Non-SCS Patients over 12-Year Study Period

Over the 12-year period, there were significant differences in overall cost metrics between the cohorts who did not undergo SCS implantation. Compared to the Commercial and Medicare cohorts, the Medicaid-cohort had the lowest median [IQR]: (1) total costs (Medicaid: $4530.4 [$1,440.6, $11,973.5], Medicare: $7292.0 [$3,371.4, $13,989.4], Commercial: $4944.3 [$363.8, $13,294.0], p<0.0001); (2) pain prescription cost (Medicaid: $32.2 [$0.0, $688.7], Medicare: $153.4 [$14.9, $725.9], Commercial: $204.7 [$15.3, $948.4], p<0.0001); and (3) cost of medications (Medicaid: $351.8 [$21.4, $3,989.7], Medicare: $3309.9 [$1,587.8, $5,652.4], Commercial: $2,118.9 [$614.3, $4,714.5], p<0.0001), Table 3.

Table 3.

Annual Cost for Non-SCS Patients 12-Year Study Period

| Variable – Median[IQR] Mean (SD) | Commercial | Medicare | Medicaid | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cost | 4944.3 [363.8, 13294.0] | 7292.0 [3371.4, 13989.4] | 4530.4 [1440.6, 11973.5] | <0.0001* |

| 9714.2 (14406.3) | 11058.7 (13291.3) | 9038.2 (12851.1) | ||

| Pain Prescriptions Costs | 204.7 [15.3, 948.4] | 153.4 [14.9, 725.9] | 32.2 [0.0, 688.7] | <0.0001* |

| 872.8 (1597.8) | 624.8 (1150.3) | 715.5 (1510.8) | ||

| Medication Costs | 2118.9 [614.3, 4714.5] | 3309.9 [1587.8, 5652.4] | 351.8 [21.4, 3989.7] | <0.0001* |

| 3254.2 (3580.8) | 4019.6 (3295.9) | 2641.6 (4126.8) | ||

| Number of Pain Prescriptions | 9.0 [2.0, 20.0] | 6.0 [2.0, 13.0] | 12.0 [0.0, 26.0] | <0.0001* |

| 12.9 (13.6) | 8.8 (9.5) | 15.8 (17.2) |

Medicare patients had lower number of pain prescriptions (Medicaid: 12.0 [0.0, 26.0], Medicare: 2.0 [0.0, 13.0], Commercial: 9.0 [2.0, 20.0], p<0.0001) compared to Commercial- and Medicaid-insured patients, Table 3.

Cost at Year of SCS Implantation

At the year of SCS implantation, there were significant differences in overall cost metrics between all the cohorts. Compared to the Commercial and Medicare cohorts, the Medicaid-cohort had the lowest median [IQR]: (1) total costs (Medicaid: $8,085.2 [$4,572.8, $14,272.9], Medicare: $12,303.6 [$8,221.7, 19,847.3], Commercial: $16,402.7 [$10,835.6, 24,508.9], p<0.0001); (2) pain-procedural costs (Medicaid: $1,446.0 [$209.7, $3,372.7], Medicare: $2475.1 [$1,188.4, 5,232.73], Commercial: $4866.1 [$2,186.3, $8,931.1], p<0.0001); (3) pain prescription costs (Medicaid: $7.7 [$0.0, $385.8], Medicare: $419.1 [$103.4, $1,217.3], Commercial: $687.9 [$189.0, $2,018.6], p<0.0001); (4) total medication costs (Medicaid: $98.3 [$2.9, $2,459.38], Medicare: $4,215.7 [$2,161.0, $6,829.9], Commercial: $3,664.8 [$1,483.7, $6,831.4], p<0.0001); and (5) number of pain prescriptions (Medicaid: 8.0 [0.0, 26.0], Medicare: 11.0 [5.0, 19.0], Commercial: 18.0 [9.0, 28.0], p<0.0001), Table 4.

Table 4.

Cost at Year of SCS Implantation

| Variable – Median[IQR] Mean (SD) | Commercial | Medicare | Medicaid | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cost | 16402.7 [10835.6, 24508.9] | 12303.6 [8221.7, 19847.3] | 8085.2 [4572.8, 14272.9] | <0.0001* |

| 19773.5 (14046.5) | 16037.7 (13676.9) | 11110.3 (9919.7) | ||

| Pain Procedural Costs | 4866.1 [2186.3, 8931.1] | 2475.1 [1188.4, 5232.7] | 1446.0 [209.7, 3372.7] | <0.0001* |

| 6247.6 (5748.6) | 3945.8 (4325.2) | 2217.1 (2505.8) | ||

| Pain Prescription Cost | 687.9 [189.0, 2018.6] | 419.1 [103.4, 1217.3] | 7.7 [0.0, 385.8] | <0.0001* |

| 1475.3 (1911.9) | 957.3 (1357.3) | 613.0 (1401.2) | ||

| Medication Costs | 3664.8 [1483.7, 6831.4] | 4215.7 [2161.0, 6829.9] | 98.3 [2.9, 2459.3] | <0.0001* |

| 4690.6 (4170.9) | 4883.3 (3638.1) | 2068.1 (3962.1) | ||

| Number of Pain Encounters | 20.0 [9.0, 35.0] | 16.0 [8.0, 30.0] | 21.0 [7.0, 36.0] | <0.0001* |

| 25.4 (23.0) | 21.7 (20.4) | 25.2 (23.4) | ||

| Number of Pain Prescriptions | 18.0 [9.0, 28.0] | 11.0 [5.0, 19.0] | 8.0 [0.0, 26.0] | <0.0001* |

| 20.0 (14.4) | 13.3 (10.5) | 14.8 (17.6) |

Medicare patients had lower number of pain-related encounters (Medicaid: 21.0 [7.0, 36.0], Medicare: 16.0 [8.0, 30.0], Commercial: 20.0 [9.0, 35.0], p<0.0001), Table 4.

Annual Cost for post-SCS Patients over 12-Year Study Period

Over the 12-year period, there were significant differences in overall cost metrics between the cohorts who underwent SCS implantation. Compared to the Medicaid and Medicare cohorts, the Commercial-cohort had the lowest median [IQR] total costs (Medicaid: $4,045.6 [$1,146.9, $11,533.9], Medicare: $7,158.1 [$3,160.4, $13,916.6], Commercial: $2,098.1 [$0.0, $8,919.6], p<0.0001), Table 5.

Table 5.

Annual Cost Over 9-Year Period Post-SCS

| Variable – Median[IQR] Mean (SD) | Commercial | Medicare | Medicaid | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cost | 2098.1 [0.0, 8919.6] | 7158.1 [3160.4, 13916.6] | 4045.6 [1146.9, 11533.9] | <0.0001* |

| 6813.5 (12390.1) | 11151.3 (20420.0) | 8164.3 (10283.7) | ||

| Pain Procedural Costs | 0.0 [0.0, 100.9] | 0.0 [0.0, 322.8] | 0.0 [0.0, 133.9] | <0.0001* |

| 711.2 (2705.7) | 640.8 (2089.8) | 439.6 (1978.3) | ||

| Pain Prescription Cost | 552.1 [103.3, 1875.2] | 341.4 [54.4, 1188.4] | 2.1 [0.0, 23.7] | <0.0001* |

| 1390.1 (1995.6) | 970.9 (1524.0) | 342.2 (1106.6) | ||

| Medication Costs | 3596.3 [1373.2, 6860.0] | 3979.3 [1916.4, 6709.8] | 61.0 [0.0, 233.6] | <0.0001* |

| 4734.2 (4418.0) | 4723.2 (3718.4) | 1309.2 (3540.6) | ||

| Number of Pain Encounters | 0.0 [0.0, 1.0] | 0.0 [0.0, 4.0] | 0.0 [0.0, 9.0] | <0.0001* |

| 4.3 (12.3) | 4.9 (11.8) | 8.6 (25.3) | ||

| Number of Pain Prescriptions | 14.0 [6.0, 25.0] | 9.0 [3.0, 17.0] | 4.0 [0.0, 20.0] | <0.0001* |

| 17.0 (13.9) | 11.4 (10.4) | 11.7 (15.9) |

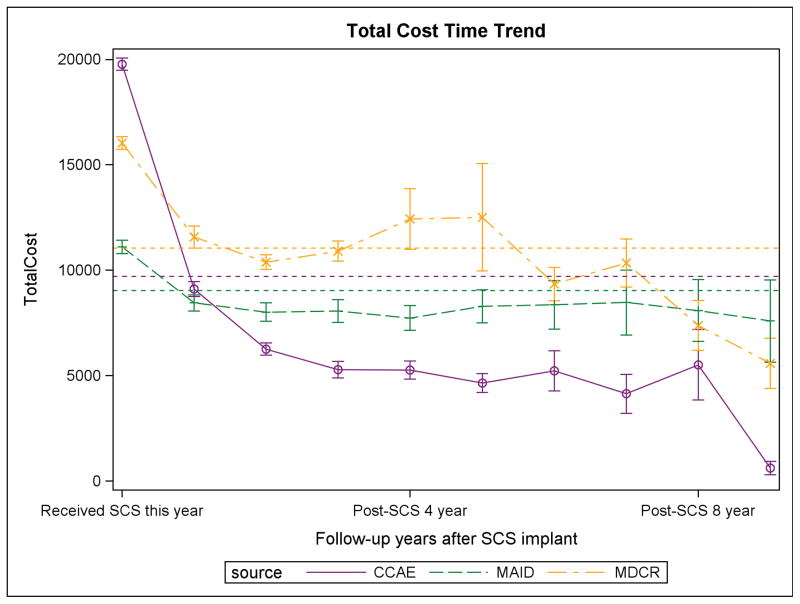

Compared to the Commercial and Medicare cohorts, the Medicaid-cohort had the lowest median [IQR]: (1) pain prescription costs (Medicaid: $2.1 [$0.0, $23.7], Medicare: $341.4 [$54.4, $1,188.4], Commercial: $552.1 [$103.3, $1,875.2], p<0.0001) and (2) medication costs (Medicaid: $61.0 [$0.0, $233.6], Medicare: $3,979.3 [$1,916.4, $6,709.8], Commercial: $3,596.3 [$1,373.2, $6,860.0], p<0.0001), Table 5. The overall 9-year total costs is depicted, Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mean (SD) total cost by insurance type up to 9 years following SCS implant. The dashed line represents the average annual total cost for the non-SCS patients in each insurance group. SCS is cost-effective across all insurance groups (Commercial>Medicaid>Medicare) beginning at 2 years and continuing through 9-year follow-up.

Multivariate Longitudinal Regression GEE Model

Table 6 is the estimated cost ratio comparing patients’ records after an SCS to those without an SCS in different insurance groups. For the baseline total cost, Commercial insurance is 0.1 times (90% lower) than Medicaid, while Medicare is 52% higher than Medicaid. Using Medicaid patients as the reference group, Medicaid patient records in the year they received SCS are expected to have a total cost 1.42 times that of records of non-SCS patients, (42% increase). For Medicare patients, patient records in the year they received SCS are expected to have a total cost 1.19 times that of records of non-SCS patients (19% increase) and 0.84 times that of Medicaid patients (16% decrease). For Commercial-insured patients, patient records in the year they received SCS are expected to have a total cost 33.6 times that of records of non-SCS patients and 23.7 times of Medicaid patients. For each unit increase of post-SCS years, Medicaid patients save 8% in total cost, while Medicare patients save 2.5%, and CCAE patient save 62% compared to the non-SCS patients. Therefore, Medicare patients are expected to have 6% higher and Commercial patients are expected to have 58% lower cost than Medicaid patients in the post-SCS period.

Table 6.

Multivariate Longitudinal Regression GEE Model

| Variable | Level | Cost Ratio | CR 5% CL | CR 95% CL | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCHRLSON | 1.21 | 1.21 | 1.22 | <.0001 | |

| Receive SCS this year | 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | . |

| 1 | 1.42 | 1.25 | 1.62 | <.0001 | |

| SEX | 1-Male | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.84 | <.0001 |

| 2-Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | . | |

| AGE | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | <.0001 | |

| Post-SCS*Post-Years | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.97 | 0.0011 | |

| PostSCS*PostYears*Insurance | Commercial | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.46 | <.0001 |

| Medicaid | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | . | |

| Medicare | 1.06 | 1.01 | 1.13 | 0.0284 | |

| Received SCS this year *(calendar year-2000) | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.07 | <.0001 | |

| insurance | Commercial | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.10 | <.0001 |

| Medicaid | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | . | |

| Medicare | 1.52 | 1.46 | 1.59 | <.0001 | |

| insurance*Receive SCS this year | Commercial | 23.7 | 21.6 | 26.0 | <.0001 |

| Medicaid | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | . | |

| Medicare | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.92 | 0.0002 |

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that Medicaid-insured patients have lower overall annual costs compared to Commercial- or Medicare-insured patients with FBSS not undergoing SCS implantation. However, Commercial-insured patients have lower overall annual costs compared to Medicaid- or Medicare-insured patients with FBSS post-SCS implantation.

Previous studies in spine-based disorders have found disparities in health care management based on patients’ insurance providers. In a case-control study of 38,092 patients with the same principle diagnoses, Ialynytchev et al. found that patients with commercial insurance were significantly associated with lumbar fusion surgery, where as Medicaid patients were negatively associated with surgery.11 Similarly, in a retrospective review of 228,882 lumbar-spine surgery patients, Jancuska et al. showed that at high volume hospitals, there are significantly more privately insured patients undergoing lumbar fusion than are Medicare and Medicaid-insured patients.12 Additionally, the authors found that Medicaid-insured patients are over-represented at low-volume centers where access to care is lower than high-volume hospitals.12 Specifically for insurance disparities in patients undergoing SCS implantation, Huang et al. found in a retrospective study of 13,774 patients that commercially insured patients had significantly higher overall costs, compared to Medicaid-insured patients, with no significant differences in complication rates.13

Analogously, our study also found that Medicaid-insured patients with FBSS had lower overall costs than Commercial- and Medicare-insured patients with FBSS and non-SCS medical therapy. These baseline cost differences could be due to the reduced number of treatment options provided to Medicaid patients who present with FBSS. However, Commercial-insured patients with FBSS undergoing SCS implantation had a lower median total cost post-SCS implantation than the Medicaid- and Medicare-insured patients. Interestingly, these findings may suggest that patients with Commercial insurance limit their need for continuous follow-up clinic visits or hospital admissions. Conversely, these differences may be due to the treatment disparities offered to the different insurance populations.

Additionally, studies suggest insurance type may also dictate the surgical approach that is performed. In the retrospective study of 13,774 who underwent SCS implantation by Huang et al., there was a significant difference the type of initial surgery performed between the cohorts, with a greater proportion of Commercially-insured patients undergoing percutaneous lead than the Medicaid-insured patient cohort (p<0.0002).13 While there is a paucity of data demonstrating differences within the SCS patient-population, there are several studies in other surgical sub-specialties that have demonstrated the impact of insurance status on surgical approach. In a retrospective study of 23,274 patients undergoing either minimally invasive surgery (MIS) or open surgery for rectal cancer, Turner et al. demonstrated in a multivariate analysis that insurance status was an independent predictor of whether a patient would receive MIS or not.14 The authors found that compared to the uninsured and Medicare/Medicaid patients, privately insured patients had significantly higher odds of receiving MIS.14 Similarly, in a retrospective study of 125,869 patients who underwent vaginal vault suspension of any type, Fack et al. found that patients with private insurance or Medicare were at significantly increased odds of undergoing robot-assisted surgery than patients with Medicaid as their primary payer.15 Furthermore, the authors found that private insurance was associated with increased reimbursement and that robot-assisted surgery was associated with $4,825 increase in hospital costs.15 Such studies suggest differences in surgical approach, combined with differences in treatment options, may explain the lower costs in Medicaid-insured patients compared to Commercial- and Medicare-insured patients in a variety of surgical disciplines.

There have also been few studies demonstrating differences in outpatient resources based on insurance provider, such as medication costs and clinic visits. In a retrospective study identifying expenditures for over-the-counter opioid prescriptions by insurance type, Zhou et al. found that Medicare spends significantly more on opioid pain relievers than does Medicaid or private insurers.16 In a epidemiologic study of 5,103 patients, Shmagel et al. demonstrated that patients with cLBP covered by government-sponsored insurance plans (Medicaid and Medicare) visit healthcare providers more frequently; thus, increasing healthcare spending.17 Analogous to these studies, our study found that along with overall costs, Medicaid patients had lower pain-related costs, pain prescription costs, and medication costs than Commercial- and Medicare-insured patients.

In efforts to reduce health care expenditures for patients with FBSS, further studies are necessary to identify the factors within each facet of healthcare management that are driving these cost differences between patients based on insurance provider. For example, Medicare costs may be proportionately increased due to the increased complexity in managing multiple co-morbidities represented in the aging population. The degree to which patients are willing and able to seek care for their FBSS might further explain the expenditure differences. Commercial-insured patients might be more willing to seek care because of their socioeconomic status, whereas patients on government-sponsored insurance plans maybe less likely to seek further care due to financial constraints. Therefore, there are many variables that may contribute to the differences in healthcare costs in FBSS patients and more studies are necessary to better identify those factors.

This is the first study to show significant differences in overall costs between insurance providers in the management of FBSS. This study, however, has limitations that have possible implications for its interpretation. First, this data was acquired retrospectively from a national database and limited by the data that was available. Second, baseline clinical states and other patient-related factors including the underlying etiology of FBSS could not be determined. Third, the patients’ specific insurance plans within their insurance package could not be discerned, which may skew the costs of care. Lastly, with most studies selecting patients using diagnosis and procedure codes, some miscoding may be present.

Despite these limitations, the comprehensive and inclusive nature of the MarketScan database provides a useful trend. This study demonstrates a significant difference in overall costs between various insurance providers in management of FBSS, with Medicaid-insured patients having lower overall costs compared to Commercial- and Medicare-patients with 5-year longitudinal data. Follow-up studies are required to delineate factors driving this difference in costs, and measures that may be taken to address existing deficits in quality of care across insurance providers.

CONCLUSION

Our study demonstrates a significant difference in overall costs between various insurance providers in the management of FBSS, with Medicaid-insured patients having lower overall costs compared to Commercial- and Medicare-patients. SCS is cost-effective across all insurance groups (Commercial > Medicaid > Medicare) beginning at 2 years and continuing through 9-year follow-up. Further studies are necessary to understand the cost differences between these insurance providers, in hopes of reducing unnecessary health care expenditures for patients with FBSS.

Footnotes

Authorship Statement: Mr. Elsamadicy and Dr. Lad designed the study. Dr. Xie and Ms. Yang conducted the study and provided the statistical analysis for analyzing the data and had complete access to the study data. We would like to

Authorship Statement: Mr. Elsamadicy, Mr. Farber, Mr. Hussaini, Ms. Murphy, Ms. Sergesketter, Mr. Surydevara prepared the manuscript draft and results with important input from Drs. Lad, Pagadala and Ms. Parente. Dr. Xie and Ms. Yang conducted the study and provided the statistical analysis for analyzing the data and had complete access to the study data. Mr. Elsamadicy, Mr. Farber, Mr. Hussaini, Ms. Murphy, Ms. Sergesketter, Mr. Surydevara provided interpretation of the data. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement: Shivanand Lad, MD, PhD, has received fees for serving as a speaker and consultant for Medtronic Inc., Boston Scientific, and St. Jude Medical. He serves as the Director of the Duke Neuro-outcomes Center, which has received research funding from NIH KM1 CA 156687, Medtronic Inc. and St. Jude Medical. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Schmidt CO, Raspe H, Pfingsten M, et al. Back pain in the German adult population: prevalence, severity, and sociodemographic correlates in a multiregional survey. Spine. 2007;32(18):2005–2011. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318133fad8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel AT, Ogle AA. Diagnosis and management of acute low back pain. American family physician. 2000;61(6):1779–1786. 1789–1790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dagenais S, Caro J, Haldeman S. A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the United States and internationally. The spine journal: official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2008;8(1):8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan CW, Peng P. Failed back surgery syndrome. Pain medicine. 2011;12(4):577–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor RS, Ryan J, O’Donnell R, Eldabe S, Kumar K, North RB. The cost-effectiveness of spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of failed back surgery syndrome. The Clinical journal of pain. 2010;26(6):463–469. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181daccec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.North RB, Kidd DH, Farrokhi F, Piantadosi SA. Spinal cord stimulation versus repeated lumbosacral spine surgery for chronic pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(1):98–106. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000144839.65524.e0. discussion 106–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Buyten JP. Neurostimulation for chronic neuropathic back pain in failed back surgery syndrome. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2006;31(4 Suppl):S25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman SD, Mackey S. Spinal cord stimulation compared with medical management for failed back surgery syndrome. Current pain and headache reports. 2009;13(1):1–2. doi: 10.1007/s11916-009-0001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollingworth W, Turner JA, Welton NJ, Comstock BA, Deyo RA. Costs and cost-effectiveness of spinal cord stimulation (SCS) for failed back surgery syndrome: an observational study in a workers’ compensation population. Spine. 2011;36(24):2076–2083. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31822a867c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lad SP, Babu R, Bagley JH, et al. Utilization of spinal cord stimulation in patients with failed back surgery syndrome. Spine. 2014;39(12):E719–727. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ialynytchev A, Sear AM, Williams AR, Langland-Orban B, Zhang N. Factors associated with lumbar fusion surgery: a case-control study. European spine journal: official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4591-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jancuska JM, Hutzler L, Protopsaltis TS, Bendo JA, Bosco J. Utilization of Lumbar Spinal Fusion in New York State: Trends and Disparities. Spine. 2016 doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang KT, Hazzard MA, Babu R, et al. Insurance disparities in the outcomes of spinal cord stimulation surgery. Neuromodulation: journal of the International Neuromodulation Society. 2013;16(5):428–434. doi: 10.1111/ner.12059. discussion 434–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner M, Adam MA, Sun Z, et al. Insurance Status, Not Race, is Associated With Use of Minimally Invasive Surgical Approach for Rectal Cancer. Annals of surgery. 2016 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flack CK, Monn MF, Patel NB, Gardner TA, Powell CR. National Trends in the Performance of Robot-Assisted Sacral Colpopexy. Journal of endourology/Endourological Society. 2015;29(7):777–783. doi: 10.1089/end.2014.0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou C, Florence CS, Dowell D. Payments For Opioids Shifted Substantially To Public And Private Insurers While Consumer Spending Declined, 1999–2012. Health affairs. 2016;35(5):824–831. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shmagel A, Foley R, Ibrahim H. Epidemiology of chronic low back pain in US adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2010. Arthritis care & research. 2016 doi: 10.1002/acr.22890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]