Abstract

Obesity is associated with increased risk for infections and poor responses to vaccinations, which may be due to compromised B-cell function. However, there is limited information about the influence of obesity on B-cell function and underlying factors that modulate B-cell responses. Therefore, we studied B-cell cytokine secretion and/or antibody production across obesity models. In obese humans, B-cell IL-6 secretion was lowered and IgM levels were elevated upon ex vivo anti-BCR/TLR9 stimulation. In murine obesity induced by a high fat diet, ex vivo IgM and IgG were elevated with unstimulated B-cells. Furthermore, the high fat diet lowered bone marrow B-cell frequency accompanied by diminished transcripts of early lymphoid commitment markers. Murine B-cell responses were subsequently investigated upon influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/34 infection using a Western diet model in the absence or presence of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA3). DHA, an essential fatty acid with immunomodulatory properties, was tested since its plasma levels are lowered in obesity. Relative to controls, mice consuming the Western diet had diminished antibody titers whereas the Western diet + DHA improved titers. Mechanistically, DHA did not directly target B-cells to elevate antibody levels. Instead, DHA increased the concentration of the downstream specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators (SPMs) 14-HDHA, 17-HDHA, and protectin DX. All three SPMs were found to be effective in elevating murine antibody levels upon influenza infection. Altogether, the results demonstrate that B-cell responses are impaired across human and mouse obesity models and show that essential fatty acid status is a factor influencing humoral immunity, potentially through an SPM-mediated mechanism.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is associated with impaired immunity, which contributes toward a variety of co-morbidities (1–4). Many factors compromise innate and adaptive immunity in the obese population, which include oxidative stress, hormonal imbalances, and nutrient overload (5–7). A considerable amount of work has defined the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which obesity promotes an inflammatory profile, particularly in adipose tissue (8, 9). In contrast, far less is known about how obesity influences humoral immunity. This is an essential gap in knowledge to address given that obesity is associated with increased susceptibility to infections and poor responses to vaccinations (10–13).

There is some evidence that humoral immunity is impaired in the obese, although there is no clear consensus. For example, hemagglutination inhibition titers (HAI), a standard assay used to determine antibody levels to influenza virus, were reported normal 30 days post-vaccination but were lowered 12 months post-vaccination in obese humans compared to non-obese subjects (13). In another study, the ability to mount influenza-specific IgM and IgG responses 8 weeks after influenza vaccination was normal in obese humans compared to lean controls, although the antibody response was diminished relative to an obese diabetic cohort (14). Mouse models also suggest that obesity impairs antibody production (15). For instance, murine HAI titers were lowered 7 days post-infection (p.i) upon influenza infection and were completely blunted by 35 days p.i. (16). Moreover, the effects of obesity are not just limited to viral infection since obese mice also have diminished antibody production upon Staphylococcus aureus infection (17).

There is strong evidence that B-cells, which have a central role in humoral immunity, regulate adipose tissue inflammation in obesity (18–21). For instance, in obese mice, IgG2c is elevated in adipose tissue and the B regulatory/B1 subsets improve adipose-tissue inflammation (22–25). In contrast, much less is known about the influence of obesity on B-cell cytokine secretion and antibody production outside of the context of adipose tissue inflammation (26). There are some conflicting reports suggesting that B-cell activity could be impaired with type II diabetes, a co-morbidity associated with obesity (20, 27). In obese type II diabetic mice, B-cells secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, similar to diabetic and/or obese patients with elevated fasting glucose (20, 28). On the other hand, newly diagnosed diabetics have suppressed B-cell inflammatory cytokines upon stimulation whereas antibody production is reported to be normal upon influenza vaccination (27, 29).

If B-cell function is potentially compromised in the obese, then it is essential to define those factors that modulate B-cell activity. Essential fatty acid status is a neglected variable in studies of humoral immunity. Essential long chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) are of interest given their immunomodulatory properties (30). Furthermore, plasma levels of long chain n-3 PUFAs are low in obese individuals compared to lean controls, which could contribute toward impairments in humoral immunity (31–33). The two major long chain n-3 PUFAs of interest are eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic (DHA) acids, which can have anti-inflammatory effects but their influence on B-cell activity is far less known (30). Our lab, in addition to other investigators, have recently discovered that n-3 PUFAs, particularly DHA, may improve B-cell driven responses, warranting more in-depth studies (34, 35).

The objectives of this study were to investigate if obesity impairs B-cell responses across three models and if essential fatty acid status has a role in modulating antibody levels. B-cell cytokine secretion and antibody production upon ex vivo stimulation were first investigated in a cohort of obese humans relative to lean controls. We next examined if a high fat (HF) diet-induced model of obesity impaired murine ex vivo antibody production and B-cell frequency in the bone marrow. Subsequently, the effects of a murine Western diet (WD) model (that provides moderate levels of fat) in the absence or presence of DHA was tested on antibody responses to influenza infection. Influenza infection, which allowed for the stimulation of B-cells in vivo, is a significant burden in the obese population (4, 36). Finally, select mechanistic underpinnings by which DHA could improve primary B-cell responses in obese mice upon influenza infection were investigated. We focused on downstream D-series specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators (SPMs) that have potent immune enhancing properties on B-cells (37, 38).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human subjects and PBMC/B-cell analyses

Human blood samples were procured after informed consent and under approval by the East Carolina University Institutional Review Board. Cells from peripheral blood were analyzed from non-obese (BMI <25 kg/m2) and obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) male subjects (Table I). The cohort included subjects that were non-smokers with exclusion criteria to be free of chronic inflammatory/autoimmune disease, not taking supplements enriched in n-3 PUFAs, and free of infection over the past month. Subjects were fasted overnight before obtaining blood.

Table I.

Patient characteristicsa.

| Parameters | Lean (n=10) | Obese (n=10) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean and range) | 34.54 (22–57) | 37.63 (22–65) |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean and range) | 24.0 (21.7–28.8) | 39.6 (30.0–65.7)**** |

| Race n (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 9 (90%) | 7 (70%) |

| African American | - | 3 (30%) |

| Indian | 1 (10%) | - |

| Medications n(%) | ||

| NSAID | 1 (10%) | - |

| PDE5 inhibitor | 1 (10%) | - |

| Phenethylamine | 1 (10%) | - |

| SSRI | 1 (10%) | 1 (10%) |

| Vitamin | 1 (10%) | - |

| ACE Inhibitor | - | - |

| Benzodiazepine | - | 3 (30%) |

| Beta Blocker | - | 1 (10%) |

| Cyclopyrrolone | - | 1 (10%) |

| HMG CoA Reductase Inhibitor | - | 1 (10%) |

| Proton Pump Inhibitor | - | 3 (30%) |

| Sulonylurea | - | 1 (10%) |

| Testosterone | - | 1 (10%) |

Subject that consumed NSAID does not have a chronic inflammatory condition.

Peripheral blood taken in vacutainer tubes was diluted 1:1 in PBS followed by separation of PBMCs using Ficoll Paque (GE Healthcare, Washington NC) gradient centrifugation. All fluorophore antibody markers used were obtained from Biolegend (San Diego CA) or Miltenyi Biotech (San Diego, CA) and consisted of: Zombie NIR, CD45 (PE), CD3 (Pacific Blue), CD4 (FITC), CD8 (PE-Cy5), CD14 (FITC), and CD19 (APC). Isolated PBMCs from gradient centrifugation were stained for viability using Zombie NIR. The following subsets were analyzed using a BDLSRII flow cytometer: CD45+CD3+CD4+, CD45+CD3+CD8+, CD45+CD3-CD14+, CD45+CD14-CD19+.

B-cells were isolated from PBMCs using a B-cell isolation kit II (Miltenyi Biotec) with a resulting purity of >99%. Purified human B-cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 5% FBS, 2mM L-glutamine, 5 × 10−5 M 2-ME, 10mM HEPES, and 50μg/ml gentamicin at a concentration of 3 × 106 cells/mL. B-cells were stimulated with: 1) CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) 2395 (a TLR9 agonist) at 1 μg/mL plus BCR stimulation using rabbit anti-human IgM Ab fragment at a concentration of 2 μg/mL; 2) PAM3CSK4 (a TLR1/2 agonist) at a concentration of 10 μg/ml. B-cells were plated in round bottom inert grade 96-well plates and cultured in duplicate for differing time points after activation. Supernatant IL-6, IL-10, and TNFα were measured using Luminex Assay kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Supernatant IgM and IgG were measured using ELISAs (Abcam, Cambridge MA) as per manufacturer’s instructions.

Obesity mouse models

Murine experiments fulfilled the guidelines established by the East Carolina University for euthanasia and humane treatment. Male C57BL/6 mice, approximately 5–7 weeks old, were fed experimental diets (Envigo, Indianapolis IN) for 15 weeks. In the first murine model, animals were fed a control (10% of total kcal from lard) or high fat diet (Research diets, New Brunswick NJ) (60% of total kcal from fat) for 15 weeks. In the second murine model, mice were fed a low fat control diet, a WD, or a WD supplemented with DHA (WD+DHA) ethyl esters (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA) of greater than 93% purity as previously described (39). The WD provided 45% of total kilocalories from milkfat. DHA accounted for 2% of total energy, which is easily achievable for humans through intake of over-the-counter or prescription supplements (40). The composition of the experimental diets is provided in Suppl. Table I.

Infection model

Animals were infected intranasally with 0.03 HAU of influenza A/PR/8/34 virus. All experiments with mice were in accordance with the guidelines set forth by East Carolina University. Mice were euthanized with CO2 inhalation followed by cervical dislocation. Tissues were harvested following euthanasia.

SPM studies in vivo

SPMs were prepared for as described (41). Six week-old C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were lightly anesthetized with isoflurane and then vaccinated with A/California/04/2009 (pdmH1N1) vaccine in the absence or presence of 1μg D-series SPMs (Cayman Chemical). Three weeks following vaccination, mice were bled and serum was analyzed for HAI and microneutralization titers against pdmH1N1 virus. In other studies, mice were given 1μg D-series SPMs in PBS/ethanol concomitant with 0.03 HAU of influenza A/PR/8/34 virus. PBS/ethanol alone served as the vehicle control.

Metabolic studies

Mice were fasted for 6 hours and the baseline glucose value was established with a glucometer. An i.p. injection provided 2.5g dextrose (Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL) per kg lean mass and glucose measurements were made from the tail vein. The HOMA-IR index was calculated as previously described (42). Echo-MRI was used as previously shown for fat/lean mass (43).

PCR

qRT-PCR analysis was conducted on total bone marrow cells and B-cells as previously described (39). The fold change from the control was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences used in the study are provided in Suppl. Table II. For PCR analyses, total RNA was isolated from sorted splenic B220+ cells using a B220+-FITC (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) antibody. 0.5μg of cDNA was synthesized using the Invitrogen First Strand Synthesis Kit (Carlsbad, CA). Both random hexamer and oligonucleotide primers were used in the reaction. Following synthesis of cDNA, PCR was conducted in a 50μL reaction mix using Invitrogen Platinum PCR SuperMix High Fidelity (Carlsbad, CA). A 300nM concentration of primer solutions was used followed by the addition of cDNA. PCR products were visualized on a 1% agarose gel.

Flow cytometry

Bone marrow was extracted as previously demonstrated (39). For consistency, the left leg was used for each mouse. The fluorescently labeled antibodies were obtained from Biolegend and consisted of: CD19 (PerCP-Cy5.5), CD43 (APC), CD24 (Pacific Blue), IgM (PE), IgD (APC), and CD138 (APC). The following B-cell subsets were analyzed: CD19-CD43+CD24− IgM− (pre-pro), CD19+CD43+CD24+IgM− (pro), CD19+CD43-CD24+IgM− (pre), CD19+CD24+IgM+IgD− (immature), CD19+IgM+IgD+ (mature), and CD19+CD138+ (plasma cells).

ELISAs, HAI, and microneutralization assays

IgM and IgG levels (Abcam, Cambridge MA) were analyzed from serum with ELISAs (34). For the HAI assay, serum was treated overnight with receptor destroying enzyme (RDE; Denka Seiken Campbell CA), followed by heat inactivation for one hour and then diluted 1:10 in PBS (16). Hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assays were performed according to WHO guidelines (Global Influenza Surveillance Network Manual for the laboratory diagnosis and virological surveillance of influenza). RDE-treated sera were incubated with 4 HAU influenza virus for 15 minutes at room temperature followed by a 1 hour incubation at 4 °C with 0.5% turkey red blood cells. HAI was calculated by taking the reciprocal of the highest dilution of serum that completely inhibited hemagglutination of the turkey red blood cells (16).

For microneutralization assays, RDE-treated sera were diluted in microneutralization media (DMEM, 2 mM glutamine, 1% bovine serum albumin) at a 1:2 dilution. Sera were then incubated with 100 TCID50 virus for 1 h at 37 °C on white polystyrene plates. Following incubation, 3×104 MDCK cells were added to each well and plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight. The bulk of the media was removed and plates were frozen for at least 30 min at −80 °C. Luminescence was determined by adding 25 μl Nano-Glo substrate solution (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the plates were placed in a Synergy H1 Hybrid Reader. Neutralization was considered to be any well below half the luminescence generated by a well infected with 100 TCID50 A/Puerto Rico/8/34 NLuc virus (44).

Lipidomic sample preparation

All standards and internal standards used for LC/MS/MS analysis were purchased from Cayman Chemical. All solvents were HPLC grade or better. Tissue homogenate samples were pretreated for solid phase extraction as follows. Briefly, a volume of tissue homogenate equivalent to 500μg was brought to a volume of 1 ml in 10% methanol along with 10μl of 10pg/μl internal standard solution (100pg total/each of 5(S)-HETE-d8, 8-iso-PGF2α-d4, 9(S)-HODE-d4, LTB4-d4, LTD4-d5, LTE4-d5, PGE2-d4, PGF2α-d9 and RvD2-d5 in ethanol).

Serum samples were pretreated for solid phase extraction. Proteins were precipitated from 50μl of serum by adding 200μl of ice cold methanol and 10μl of the internal standard solution, followed by vortexing and then incubating on ice for 15 minutes. The samples were then placed in a microcentrifuge for 10 minutes at 4°C at 14,000 RPM. A 200μl portion of the supernatant was diluted to 10% methanol by adding 1.4ml of water. Lipid mediators were isolated from the pretreated samples by solid phase extraction as described (45). Lipid mediators were extracted using Strata-X 33um 30mg/1ml SPE columns (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) on a Biotage positive pressure SPE manifold. Columns were washed with 2ml of methanol followed by 2ml of H2O. After applying the sample, the columns were washed with 1ml of 10% methanol and the lipid mediators were then eluted with 1ml of methanol directly into a reduced surface activity/maximum recovery glass autosampler vial. The methanol solvent was then evaporated to dryness under a steady stream of nitrogen directly on the SPE manifold. The sample was immediately reconstituted with 15–20μl of ethanol and analyzed immediately or stored at −70°C until analysis for no more than 1 week.

Lipid mediators in whole spleen samples were isolated as described by Yang et al (46). Spleen samples were pre-weighed and transferred into a 1.5ml microcentrifuge tube. 1ml of methanol and 10μl of internal standard solution was added and then the sample was vortexed and stored overnight at −20°C. The sample was transferred to a DUALL all glass size 21 tissue homogenizer and ground until completely homogenized. The homogenate was transferred to a 1.5ml centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 14,000 RPM for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was diluted to 10ml with water adjusted to pH 3.5. The samples were then applied to Hypersep C18 500mg/6mL SPE columns (Thermo-Fisher) that were prewashed with 20ml of methanol followed by 20ml of water. The SPE columns were washed with 10ml of water followed by 10ml of hexane. Lipid mediators were eluted with 8ml of methyl formate (eicosanoids and docosanoid fraction) followed by 10ml of methanol (cysteinyl leukotriene fraction). Both fractions were dried under a stream of nitrogen and reconstituted with ethanol and combined into a reduced surface activity/maximum recovery glass autosampler vial analyzed immediately or stored at −70°C until analysis for no more than 1 week.

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

Quantitation of lipid mediators was performed using 2 dimensional reverse phase HPLC tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS). The HPLC system consisted of an Agilent 1260 autosampler (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara CA), an Agilent 1260 binary loading pump (pump 1), an Agilent 1260 binary analytical pump (pump 2) and a 6 port switching valve. Pump 1 buffers consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and 9:1 v:v acetonitrile:water with 0.1% formic acid (solvent B). Pump 2 buffers consisted of 0.01% formic acid in water (solvent C) and 1:1 v:v acetonitrile:isopropanol (solvent D).

10μl of extracted sample was injected onto an Agilent SB-C18 2.1X5mm 1.8um trapping column using pump 1 at 2ml/min for 0.5 minutes with a solvent composition of 97% solvent A: 3% solvent B. At 0.51 minutes the switching valve changed the flow to the trapping column from pump 1 to pump 2. The flow was reversed and the trapped lipid mediators were eluted onto an Agilent Eclipse Plus C-18 2.1X150mm 1.8um analytical column using the following gradient at a flow rate of 0.3mls/min: hold at 75% solvent A: 25% solvent D from 0–0.5 minutes, then a linear gradient from 25–75% D over 20 minutes followed by an increase from 75–100% D from 20–21 minutes, then holding at 100% D for 2 minutes. During the analytical gradient pump 1 washed the injection loop with 100% B for 22.5 minutes at 0.2ml/min. Both the trapping column and the analytical column were re-equilibrated at starting conditions for 5 minutes before the next injection.

Mass spectrometric analysis was performed on an Agilent 6490 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer in negative ionization mode. The drying gas was 250°C at a flow rate of 15ml/min. The sheath gas was 350°C at 12mls/min. The nebulizer pressure was 35psi. The capillary voltage was 3500V. Data for lipid mediators was acquired in dynamic MRM mode using experimentally optimized collision energies obtained by flow injection analysis of authentic standards. Calibration standards for each lipid mediator were analyzed over a range of concentrations from 0.25–250pg on column. Calibration curves for each lipid mediator were constructed using Agilent Masshunter Quantitative Analysis software. Tissue and serum samples were quantitated using the calibration curves to obtain the column concentration, followed by multiplication of the results by the appropriate dilution factor to obtain the concentration in pg/μg of protein (tissue homogenates) or pg/ml (serum).

Proliferation assays

B-cell pellets were stored for a minimum of 24 hours at −80°C. A CyQUANT cell proliferation assay kit (Eugene, OR) was used to quantify number of cells per well and as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vitro studies

Mouse splenic B-cells were plated in 96 well plates at 1×106/ml and activated with: 1) 1μg/ml CpG 1826 (Novus Biologicals, Littleton CO) plus 2μg/ml anti-IgM (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Baltimore Pike PA) or 2) 1μg/ml LPS (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis MO). Cells were also treated with 5μM Rosiglitazone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO) or 5μM DHA (Cayman Chemical) and then activated thirty minutes later with 1μg/ml CpG 1826 plus 2μg/ml anti-IgM. DHA stocks were conjugated to BSA as previously described (47).

Statistics

All murine results are from multiple cohorts of mice. Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism version 5.0b. IgM and IgG levels assayed in human studies were fit using linear regression analysis. Most data sets displayed normalized distributions as determined by a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Statistical significance for human studies, in vitro experiments, and those experiments comparing lean versus HF fed mice were analyzed with a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. All other analyses relied on one-way or two-way ANOVAs followed by a post-hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison tests. Those data sets that did not display normalized distributions were analyzed with a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparison test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

B-cell IL-6 secretion is lowered and IgM levels are elevated in obese humans

We first studied B-cell responses in a cohort of age-matched non-obese and obese males that considerably differed in body mass index (BMI, Table 1). Flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Fig. 1A) generally revealed an increased percentage of B-cells (P=0.05) in obese individuals with no effect on monocytes, CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1B). When B-cells were enumerated with trypan blue exclusion upon purification of the cells, there was a significant increase in B-cell frequency in the obese subjects compared with non-obese controls (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. B-cell IL-6 secretion and IgM production are modified in human obesity.

(A) Sample flow cytometry data showing the percentage of B-cells, monocytes, helper CD4+, and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. (B) Quantification of the percentage of CD45+ cells in PBMCs. (C) Frequency of B-cells isolated via negative selection from non-obese and obese subjects and enumerated with trypan blue exclusion. (D) Purity of B-cells as measured by CD19/CD14 staining with flow cytometry. (E) B-cell cytokine secretion upon CpG-ODN + anti-IgM or PAM3CSK4 stimulation. Correlation plots of (F) IgM and (G) IgG upon stimulation with CpG-ODN+anti-IgM with BMI. Data are average ± S.E.M. N=10 lean and 10 obese subjects for B,D and N=16 subjects for F–G. *P<0.05, by unpaired Student’s t test (B,C,E). Correlation plots (F–G) relied on linear regression analyses.

Highly purified B-cells, as assessed by CD14 and CD19 staining (Fig. 1D), were used for measuring cytokine and antibody production. IL-6 secretion in response to activation with CpG-ODN (TLR9 agonist)+anti-IgM (for BCR engagement) was ~35–40% lower in B-cells from obese relative to non-obese subjects with no significant effect on TNFα or IL-10 secretion (Fig. 1E, left panel). B-cell cytokine secretion from obese subjects was not affected upon targeting of TLR1/2 with PAM3CSK4 relative to controls (Fig. 1E, right panel). Cytokine secretion was not detectable in the absence of CpG-ODN+anti-IgM or PAM3CSK4 stimulation (data not shown). Activation of B-cells with CpG-ODN+anti-IgM revealed a correlation between increasing IgM levels (Fig. 1F) and increasing BMI, with no correlation between IgG levels and BMI (Fig. 1G). Thus, the studies with human subjects showed obesity dysregulated B-cell cytokine secretion and antibody production upon CpG-ODN+anti-IgM stimulation.

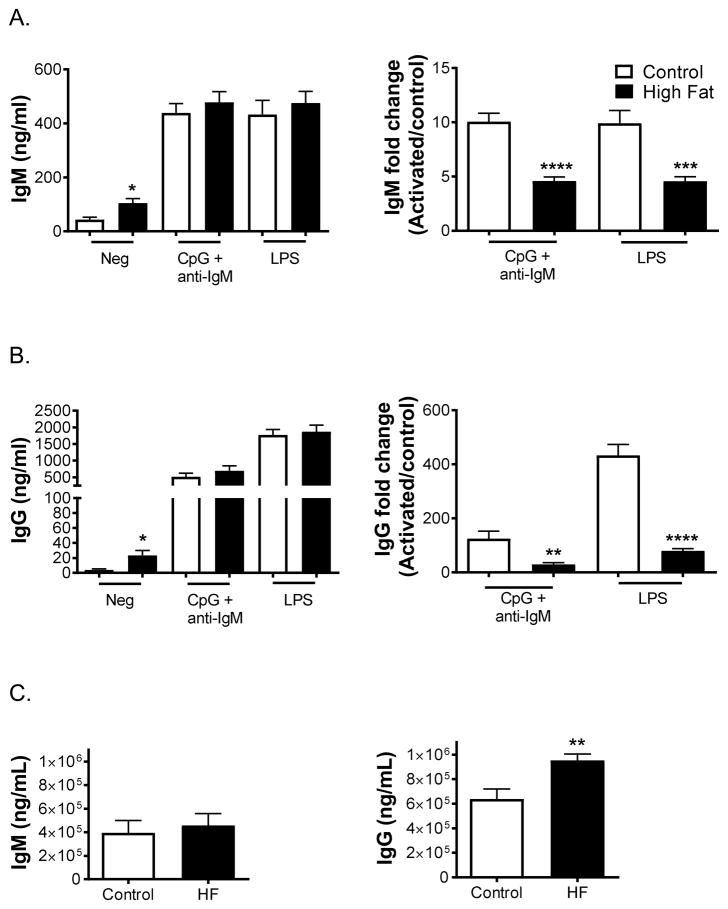

B-cell IgM and IgG levels are elevated in the absence of stimulation for mice consuming a high fat diet

Experiments were next conducted in a mouse model to determine if murine B-cell activity was also impaired in response to diet-induced obesity. Ex vivo splenic B-cell antibody production was measured using lean and HF diets. Mice consuming the HF diet displayed elevated levels of ex vivo IgM (Fig. 2A, left panel) and IgG (Fig. 2B, left panel) in the absence of stimulation. There was no absolute change in IgM (Fig. 2A, left panel) or IgG (Fig. 2B, left panel) production with the HF diet upon stimulation with either CpG-ODN+anti-IgM or LPS. However, relative to the negative controls, the increase in IgM (Fig. 2A, right panel) and IgG (Fig. 2B, right panel) levels for obese mice upon stimulation with either CpG-ODN+anti-IgM or LPS were diminished by 2-fold or greater relative to the control mice. Circulating IgM (Fig. 2C, left panel) and IgG (Fig. 2C, right panel) levels were also assayed and there was a significant increase in the levels of IgG with obese mice.

Figure 2. B-cell IgM and IgG levels are elevated in the absence of stimulation with mice consuming high fat diets.

(A) IgM and (B) IgG levels from splenic B-cells in the absence and presence of CpG-ODN+anti-IgM or LPS stimulation. Fold changes in IgM and IgG relative to the negative control are depicted to the right. Circulating (C) IgM and IgG levels for mice consuming a lean control or high fat diet. Mice were fed experimental diets for 15 weeks. Data are average ± S.E.M. N=6–7 mice per diet. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 by unpaired Student’s t test.

The frequency of bone marrow B-cell subsets is lowered in mice consuming a high fat diet

In parallel with the ex vivo studies, we probed for potential defects in B-cell development (Fig. 3). The percentage (Fig. 3A, left panel) and frequency (Fig. 3A, right panel) of B-cells in the bone marrow were lowered with the HF diet relative to the lean control by ~2-fold. B-cell subsets were further analyzed with flow cytometry (Fig. 3B). There was attenuation in the percentage of CD19+IgM-CD43-CD24+ cells with mice consuming the HF diet compared to the control (Fig. 3C, left panel). The frequency of all the major B-cell subsets were lowered with the HF diet relative to the control (Fig. 3C, right panel). In addition, CD138+ B-cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 3D). The percentage (Fig. 3E, left panel) and frequency (Fig. 3E, right panel) of CD138+ B-cells in the bone marrow were lowered with the HF diet compared to the control by 1.7–2-fold. B-cell proliferation was not influenced by the HF diet relative to the lean control (data not shown).

Figure 3. The frequency of bone marrow B-cell subsets is lowered in mice consuming a high fat diet accompanied by diminished early lymphoid commitment markers.

(A) Percentage and frequency of total B-cells in the bone marrow of mice consuming control and high fat diets. (B) Sample gating strategy for analyzing B-cell subsets in the bone marrow. (C) Percentage and frequency of B-cell subsets in the bone marrow. (D) Sample gating strategy for analyzing CD138+ B-cells in the bone marrow. (E) Percentage and frequency of CD138+ B-cells for lean and obese mice. (F) Transcript levels of key early, intermediate, and late B-cell development markers assayed on total bone marrow cells. Mice were fed a control or a high fat diet for 15 weeks. Data are average ± S.E.M. N=5–7 mice per diet for A,C,E and 10–11 mice per diet for F. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 by unpaired Student’s t test.

To explain the reduction in the proportion of B-cells in the bone marrow, select markers relevant to early lymphoid commitment were assayed at the mRNA level from isolated bone marrow cells (Fig. 3F). We specifically focused on the early lymphoid commitment markers IL7-Rα, IL-7, and STAT5 (Fig. 3F) (48, 49). With mice consuming the high fat diet relative to lean controls, bone marrow transcripts of IL7-Rα and IL-7 were decreased by ~2-fold, whereas STAT5 showed a trend toward being lowered (P=0.08). Markers of intermediate (PAX5 and OCT2) and late B-cell development (Blimp1) were also assayed (50, 51). These markers, which may reflect the decrease in B-cell subset frequency, were also lowered by 2-fold or greater in the bone marrow of mice on a HF diet compared to controls (Fig. 3F).

The antibody response is decreased in a murine WD model and improved by DHA upon influenza infection

The next set of studies focused on how a moderate WD model in the absence or presence of DHA would influence primary B-cell responses, which was assayed in response to a mouse-adapted influenza stain (18). DHA was specifically used since essential fatty acid levels are lowered in obesity (31). The composition of the diets was routinely verified to ensure the absence of DHA in the WD compared to WD+DHA and diets were also continuously monitored for the lack of oxidation prior to and during the course of the study (data not shown). Prior to infection, body weights were elevated for both Western diets compared to the control (Fig. 4A), which was driven by an increase in fat mass and not lean mass (Fig. 4B). The HOMA-IR index, a measure of glucose/insulin sensitivity, was elevated for mice fed both Western diets relative to the lean mice (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. A Western diet suppresses antibody titers, which are improved with the essential fatty acid DHA.

(A) Body weights of mice prior to infection after 15 weeks of dietary intervention. (B) Lean and fat mass as measured by Echo-MRI. (C) HOMA-IR index calculated from fasting glucose/insulin. Mice were fasted for 6 hours prior to measurements. (D) HAI titers for C57BL/6 mice that were fed a control, Western diet, or Western diet + DHA diets for 15 weeks followed by influenza infection. (E) Percentage of mice showing HAI antibodies at day 7 p.i. (F) Microneutralization titers for C57BL/6 mice that were fed a control, Western diet, or Western diet + DHA diets for 15 weeks followed by influenza infection for 21 days. (G) Absolute weight loss and (H) percent weight loss as a function of time. Data are average ± SEM. N=4–9 mice per diet for A–F and 15–20 mice per diet for G–H. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-test (A,B,C, F) or a two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-test (D,G,H).

Infection studies revealed that on day 7 post-infection (p.i.), the WD fed mice tended to have lower HAI titers, similar in magnitude to those from a previous report (16). Inclusion of DHA in the diet increased the HAI titers relative to the WD by 4-fold (Fig. 4D). HAI titers were not assessed on day 14 p.i. given that mice consuming a WD show no impairment in antibody production at this time point (16). Notably, on day 7 p.i., only 66% of the mice consuming the WD had measurable HAI titers (Fig. 4E), consistent with previous work (16). On day 21 p.i., HAI titers were lowered in mice fed the WD by ~43% compared to the lean control (Fig. 4D). DHA improved the titers compared to the WD by 25% but not to the same level as the control (Fig. 4D). Given that DHA showed a modest effect on HAI titers at 21 days p.i., we further investigated using a microneutralization assay. This assay revealed that the WD lowered titers (p=0.06) by 2.6-fold relative to the lean control and the inclusion of DHA in the diet improved titers by 3.7-fold relative to WD (Fig. 4F).

Recovery of the mice in response to the infection was also measured. Mice consuming the WD did not have a significant difference in recovery, as measured by the total loss of body mass, compared to the control diet in the early part of the time course; however, on day 14 p.i. the body mass of mice on the WD was significantly lower compared to the control and WD + DHA (Fig. 4G). When calculated as the percent weight loss, the WD+DHA modestly improved recovery relative to the WD at days 7–10 p.i. (Fig. 4H). The results from this model further established compromised B-cell responses with obesity and highlighted the importance of essential fatty acid status.

DHA is not directly targeting B-cells suggesting a role for downstream SPMs

The next objective was to establish how DHA could enhance antibody titers. We first focused on DHA binding the G-protein coupled receptor (GPR)120, a sensor for DHA reported to be on the surface of macrophages but not investigated with B-cells (52). PCR analysis of sorted B-cells showed very low abundance of GPR120 compared to epididymal adipose tissue and activation of B-cells with GPR120 agonists did not promote antibody production (data not shown).

A second possibility was DHA directly targeting B-cells to increase antibody levels, potentially by binding PPARγ. Activation of B-cell PPARγ with agonists boosts antibody levels in human B-cells although less is known about mouse B-cells (53). Thus, to first determine that PPARγ activation promotes antibody production in mouse cells, splenic B-cells were pre-treated with 5μM Rosiglitazone, a PPARγ agonist. Stimulation in the presence of Rosiglitazone with CpG-ODN+anti-IgM increased IgG but not IgM levels after 3 days (Suppl. Fig. 1A) and both IgM and IgG were elevated after 6 days (Suppl. Fig. 1A). The increase in antibody levels was not driven by an increase in the proliferation of the B-cells (Suppl. Fig. 1B) as reported for human B-cells (53). Given that PPARγ stimulation enhanced antibody production in mouse B-cells, we next tested the effects of in vitro treatment with DHA, a known PPARγ agonist. When B-cells were treated with 5μM DHA for 3 days, IgM and IgG levels were dramatically lowered (Fig. 5A) in parallel with a decrease in B-cell proliferation (Fig. 5B) compared to a bovine serum albumin (BSA) control. This ruled out that DHA was having a direct effect on the B-cells as a PPARγ agonist. Conversely, the results suggested DHA by itself lowered B-cell proliferation and activity.

Figure 5. DHA is not directly targeting B-cells to boost antibody production suggesting a role for D-series SPMs.

(A) IgM and IgG levels upon treatment of splenic B-cells with 5μM DHA. DHA was added 30 minutes prior to activation with CpG-ODN+anti-IgM and was further added each day for 3 days. BSA served as a control since DHA was complexed to BSA. (B) Proliferation of B-cells in response to DHA treatment. (C) Pathway by which DHA promotes production of downstream SPMs. LOX is for lipoxygenase. (D) HAI and (E) microneutralization titers of mice after vaccination with pdmH1N1 vaccine in response to vehicle control or SPM injection. (F) Sample PCR data showing mRNA expression of ALX/FPR2, ChemR23, and BLT1 for sorted splenic and bone marrow B-cells. Peritoneal macrophages were used for comparative purposes. (G) Quantification of mRNA expression of ALX/FPR2, ChemR23, and BLT1. Data are average ± S.E.M. N=3–5 independent experiments except F, which is a single experiment representative of 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 by unpaired Student’s t test (A) or two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-test (B), or a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparison test (D–E).

We then tested the possibility that D-series SPMs synthesized from DHA could boost antibody production (Fig. 5C). The SPM 17-HDHA is reported to increase antibody levels in vitro and in a pre-clinical model of vaccination (41, 54). Given that DHA would likely give rise to multiple SPMs in vivo, several D-series SPMs downstream of 17-HDHA were tested. We used a pre-clinical vaccination model used for 17-HDHA in order to directly compare our results (54). HAI titers (Fig. 5D) were significantly elevated, compared to the vehicle control, with resolvin D1 (RvD1), resolvin D2 (RvD2), and protectin DX (PDX). Microneutralization titers revealed a similar trend with the exception of RvD2 in boosting antibody levels (Fig. 5E).

We confirmed that B-cells express multiple receptors that could respond to differing SPMs (Fig. 5F). Sorted splenic and bone marrow B-cells expressed the SPM receptors ALX/FPR2 and ChemR23 at the mRNA level (Fig. 5G). In comparison, transcript levels of BLT1, the receptor for LTB4 and RvE1 was robustly expressed at the mRNA level in B-cells (Fig. 5G). Splenic B-cell transcripts of ALX/FPR2 and ChemR23 were notably lower than peritoneal macrophages, which were used as a control since they expressed high levels of the SPM receptors (37).

DHA increases D-series SPMs in the WD model accompanied by an increase in the frequency of CD138+ cells

The next set of experiments tested the possibility that DHA would increase downstream SPMs in mice consuming the WD at 7 days p.i. Lipid mediators (Figs. 6A–D) were first assayed in serum to assess circulatory levels. SPMs were not significantly elevated in serum in response to DHA in the diet (Fig. 6E). Since there is debate as to whether SPMs are measurable in circulation (55, 56), levels of D-series SPMs were also measured in the spleen. In the spleen, the WD+DHA increased the levels of 14-HDHA and 17-HDHA by up to 2-fold compared to the WD and/or the control (Fig. 6F). PDX levels were lowered by 50% with the WD compared to the control. RvD2 levels trended (p=0.07) in a downward fashion with the WD compared to the control (Fig. 6F). PDX and RvD2 levels were generally restored to control levels with WD+DHA (Fig. 6F). The increase in D-series SPMs, particularly in spleen, were accompanied by a reduction in a range of n-6 PUFA derived mediators, notably those derived from arachidonic acid (Suppl. Fig. 2A–B) with some additional changes in linoleic acid-derived mediators with both Western diets (Suppl. Fig. 2C–D).

Figure 6. DHA enhances downstream D-series SPM levels of mice consuming a Western diet.

Extracted ion chromatograms (A and C) and product ion spectra (B and D) for 10(S),17(S)-DiHDoHE (protectin DX – PDX) in mouse serum (A and B) and authentic standard (C and D). Specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators synthesized from DHA in murine (E) serum and (F) spleen at 7 days p.i. upon consuming a control, Western diet, or Western diet + DHA for 15 weeks. N=5–10 mice per diet. Samples for serum analyses required the pooling of 2 mice per experiment. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-test.

Since 17-HDHA is reported to increase antibody production by increasing the frequency of bone marrow CD19+CD138+ plasma cells (41, 54), and DHA elevated 17-HDHA, we determined if DHA elevated the production of CD19+CD138+ cells at day 21 p.i. The frequency of B-cells was slightly lowered by the WD relative to the control (Fig. 7A). There was no change in the percentage (Fig. 7B, left panel) or frequency (Fig. 7B, right panel) of the major B-cell subsets with either Western diet. Upon flow cytometry analysis of the CD138+ population (Fig. 7C), the WD diet tended (p=0.07) to lower the percentage of CD138+ cells relative to the control (Fig. 7D, left panel). The percentage (Fig. 7D, left panel) and frequency (Fig. 7D, right panel) of CD138+ cells increased with the WD+DHA compared to the WD. Thus, the phenotyping data revealed that DHA enhanced the frequency of CD138+ cells in the bone marrow, further suggesting a mechanism mediated by 17-HDHA (41, 54).

Figure 7. DHA increases the frequency of bone marrow CD138+ plasma cells in mice consuming a Western diet.

(A) Number of isolated B-cells in bone marrow for mice consuming a control, Western diet, or Western diet + DHA for 15 weeks. (B) Percentage and frequency of B-cell subsets. (C) Sample flow cytometry data of long-lived CD138+ plasma cells in bone marrow for mice consuming a control, Western diet, and Western diet + DHA. (D) Percentage and frequency of CD138+ plasma cells in bone marrow. The results are from 21 days post-infection. Data are average ± S.E.M. N= 7–8 mice per diet. *P<0.05 by one-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-test.

Administration of D-series SPMs after infection boosts antibody titers

The next set of experiments tested the possibility that 17-HDHA and perhaps other D-series SPMs would boost antibody titers. Mice were injected with 17-HDHA 24 hours after the administration of the influenza virus and antibody titers were assayed at 14 days p.i. Given that the lipidomic data showed DHA elevated 14-HDHA and PDX, these molecules were also specifically tested. HAI (Fig. 8A, left panel) and microneutralization (Fig. 8A, right panel) titers were elevated with 14-HDHA, 17-HDHA, and PDX. Body weight analysis over the course of the infection showed no effect of 14-HDHA, 17-HDHA, or PDX on murine recovery compared to the vehicle control (data not shown).

Figure 8. 14-HDHA enhances antibody titers accompanied by an increase in CD138+ cells upon influenza infection.

(A) HAI and microneutralization titers upon administering select D-series SPMs 24 hours post-infection. (B) HAI and microneutralization titers upon administering select D-series SPMs in parallel with influenza infection. HAI and microneutralization titers were assayed in A–B at 14 days p.i. (C) Sample flow cytometry plots of CD138+ cells on day 21 p.i. for mice treated with 14-HDHA, 17-HDHA, or PDX. (D) Average percentage and frequency of CD138+ cells. Data are average ± S.E.M. N= 3–5 mice per treatment. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 by unpaired Student’s t test.

14-HDHA administered with infection enhances antibody titers accompanied by an increase in the frequency of CD138+ cells

We finally tested if administration of the three SPMs had the same effect when administered in parallel with the infection. Surprisingly, HAI (Fig. 8B, left panel) and microneutralization (Fig. 8B, right panel) titers were only elevated with 14-HDHA, but not 17-HDHA or PDX. We further probed if 14-HDHA was selectively promoting the production of CD138+ cells in the bone marrow at day 21 p.i. (Fig. 8C). Flow cytometry analyses revealed a 2-fold or greater elevation in the percentage (Fig. 8D, left panel) and frequency (Fig. 8D, right panel) of CD138+ cells with 14-HDHA but no effect of 17-HDHA or PDX. Thus, these results showed that SPMs have differing effects on antibody production depending on the time of the administration and notably, 14-HDHA increased antibody levels accompanied by an increase in CD138+ cells.

DISCUSSION

B-cell activity is modified across obesity models

The results of our study demonstrate that B-cell cytokine secretion and/or antibody production are modified across mouse and human obesity models. Few studies in humans have directly investigated whether B-cell function is impaired with obesity; therefore, this was first addressed by testing how ex vivo B-cell cytokine secretion and antibody production were influenced in obese subjects. Notably, IL-6 secretion was lowered upon BCR/TLR9 activation, which agrees with a report revealing that B-cell cytokine secretion can be suppressed in early stage diabetics (27). However, the cytokine data were not in complete agreement with results showing LPS enhances some pro-inflammatory cytokines in obesity from human or mouse B-cells upon ex vivo stimulation (28). We hypothesize that this is likely driven by differences in signaling pathways (i.e. TLR4 compared to BCR/TLR9) and our human subjects were mostly free of a diagnosis of type II diabetes and therefore may not display elevated B-cell cytokines. An additional finding with human subjects was an increase in the frequency of B-cells, which was consistent with data showing an enhanced percentage of B-cells in obese and type II diabetic patients (14).

The human and mouse models of obesity revealed several changes in B-cell antibody production. In humans, IgM but not IgG levels positively correlated with increasing BMI upon BCR/TLR9 stimulation. In contrast, the HF diet elevated murine IgM and IgG levels prior to BCR/TLR9 stimulation, suggesting hyperstimulated B-cells that did not respond efficiently to BCR/TLR9 or TLR4 stimulation when comparing antibody levels between the stimulated and unstimulated conditions. This result supports the emerging notion that hyperstimulated B-cells function sub-optimally (20, 57). The differences in antibody production between the human and mouse data were not entirely surprising given differing model systems. One clear set of distinctions between mice and humans was that diet was not controlled for in the human studies and the human population is genetically diverse. Future studies will need to address differences in B-cell responses between mouse and human models.

The mechanism(s) by which obesity impairs B-cell production of antibody is likely pleiotropic. Upon affinity maturation, B-cells differentiate into plasma cells that are responsible for secretion of high affinity class-switched antibodies, which are essential for prolonged protective immunity. In the HF diet model, there was a clear reduction in the percentage of bone marrow CD138+ B-cells and a similar trend was observed in the WD model. Furthermore, in the HF diet model, there was a decrease in B-cell frequency and subsequent PCR analyses revealed a decrease in key transcripts for early lymphoid commitment, which was likely driven by defects in the bone marrow environment (58). To exemplify, mRNA levels of IL-7 were lowered, which is important since IL-7 is secreted by stromal cells in the bone marrow and is a key growth factor for commitment toward the lymphoid lineage (59). A decrease in IL-7 levels would then impair signaling through IL7-Rα and downstream activation of STAT5 (48). The decrease in plasma cells could be attributed to the reduction of Blimp1, a transcription factor necessary for plasma cell generation (51). Alternatively, the reduction in Blimp1 and other markers that were assayed for intermediate B-cell development in bone marrow mRNA may simply reflect the reduction in the frequency of bone marrow CD19+ cells driven by decreased IL7-Rα signaling.

The hyperstimulation of B-cells observed with the HF diet may be driven by several factors. Recent data suggest that circulating leptin, which is elevated in obesity, may be driving hyperstimulation of B-cells (20). Specifically, B-cells from obese individuals have elevated levels of intracellular TNFα, which negatively correlates with their functional capacity (20). Therefore, leptin could be a potential factor that could be promoting antibody production under basal conditions from the B-cells of obese mice. These could also be other factors in obesity such elevated fasting insulin or glucose that could be influencing antibody production.

A key mechanism that could impair B-cell antibody production could be through the loss of essential fatty acids and thereby SPMs in obesity. There is evidence demonstrating that obese children and adults have low levels of circulating essential fatty acids including DHA, which could then impair many aspects of innate and adaptive immunity (30–33, 60). The reduction in DHA levels in obese subjects could be driven by low consumption of essential fatty acids in the diet and/or potential genetic modifications to key enzymes that metabolize DHA (33). We did not assay for circulating levels of essential fatty acids in this study. However, we did measure plasma D-series SPM concentration between lean and obese humans but SPM levels were at the lower limit of detection (data not shown), which could be due to sample degradation during the course of the clinical study.

The lipidomic data from the mice consuming the WD showed PDX levels were lowered in mice consuming the WD relative to the control, and RvD2 levels showed a strong trend to be diminished compared to the lean control. Suppressed levels of PDX and other SPMs (which were not probed for such as E-series SPMs or the PDX isomer PD1) could be driving the inability to mount effective antibody responses to influenza (61). There is precedence for the lowering of specific SPM precursors and SPMs in mouse and human obesity in select adipose tissue depots (62–64). For instance, the levels of PD1, 14-HDHA, and 17-HDHA are lowered in adipose tissue of obese mice, relative to controls, which contributes toward chronic inflammation (62, 65). Furthermore, 14-HDHA and 17-HDHA have also been shown to be decreased upon wound closure in obese diabetic mice (66). Therefore, future studies will need to address how lowering of circulating D-series SPM levels, potentially through a decrease in DHA levels or in essential fatty acid metabolism, could impair B-cell responses such as class switching and production of antibodies.

DHA’s action through SPMs

Ramon et al. demonstrated 17-HDHA boosted antibody production driven by the production of CD138+ plasma cells in the bone marrow (54). Therefore, we investigated if DHA was enhancing the production of CD138+ plasma cells and indeed observed a modest increase in this B-cell population. Contrary to our expectations, when we tested the effects of administering 17-HDHA, 14-HDHA, and PDX during the onset of infection, 14-HDHA enhanced antibody titers accompanied by an increase in the frequency of CD138+ cells. However, 14-HDHA, similar to DHA, did not improve the body weights of the mice after infection. We also found no effect of DHA on survival upon infection in a preliminary study (data not shown). This suggests that perhaps the dose of DHA in the diet or a single injection of 14-HDHA are insufficient to improve body weights upon infection. Furthermore, DHA may be enhancing the production of antibodies in obese mice without conferring protection. Indeed, a recent study showed that obese mice, despite generating neutralizing and non-neutralizing antibodies upon adjuvanted influenza vaccination, failed to be protected upon challenge with influenza virus (67).

The effects of DHA are probably not just through 14-HDHA. Given that DHA promoted higher levels of other SPMs, the effects of DHA are likely driven by a combination of several SPMs, which may exert their effects at differing time points. This is relevant given that when 17-HDHA, 14-HDHA, and PDX were administered 24 hours after the infection, antibody titers were also elevated. Furthermore, the studies with RvD1, RvD2, and PDX showed that all tested SPMs enhanced HAI titers in a pre-clinical vaccination model. Thus, future studies will likely require testing of combinations of SPMs to boost antibody production in obese mice. In addition, subsequent experiments using B-cell specific knockouts and knockdowns of SPM receptors will need to be generated to establish cause-and-effect of DHA. This will require investigating if there are additional B-cell SPM receptors besides the ones analyzed here that may be responsive to differing SPMs. Furthermore, the effects of DHA through SPM production are likely not just through B-cells but may be targeting many other cell types such follicular helper T cells (TFH) that would ultimately influence antibody production.

Several SPMs generated from DHA may also exert potential beneficial effects within the lungs where viral transcript levels were lowered upon infection in the presence of DHA (data not shown). This was not surprising given a report showing that influenza virus levels in a mouse model were lowered with PDX (68). Inclusion of DHA in the diet also promoted robust changes with n-6 PUFA derived mediators, particularly in the spleen where arachidonic acid derived mediators were lowered. Collectively, the lipidomic results provide a roadmap for future studies on how select lipid mediators from n-6 fatty acids could also target humoral immunity in obesity. As an example, when PGE2 is knocked down, responses to influenza infection are improved (69). Therefore, how DHA and/or SPMs target PGE2 is of relevance given its role in influenza infection. Thus, the results open the door for screening additional lipid mediators that may regulate the humoral immune response (70).

A striking and unexpected finding came from the in vitro experiments with DHA. DHA in culture robustly lowered antibody production from B-cells and this finding was consistent with the notion that DHA is generally immunosuppressive when directly interacting with dendritic cells or helper CD4+ T cells (71, 72). These results suggest DHA’s mechanism of action in vivo is not directly due to DHA acting on the B-cells. It is likely that there are competing effects of DHA and its downstream mediators on B-cell activity. There is literature precedence to show differing effects of DHA-derived lipid mediators on B-cell responses. For instance, 17-HDHA boosts B-cell antibody production by promoting the formation of long lived plasma cell but dampens differentiation of naïve B-cells into IgE-secreting cells (73).

Essential fatty acid status is not well controlled for in immuno-metabolism studies

A notable conclusion from these studies is that essential fatty acid status influences humoral immunity and needs to be controlled for in mouse and human studies. In fact, various dietary fat sources are employed in high fat diets and typically the fat source is lard in addition to the use of coconut oil, palm oil, milkfat and/or soybean oil (74). Therefore, the use of different fat sources for immunological studies raises the concern that functional and mechanistic outcomes could be confounded by variations in the composition of the fat, such as essential fatty acids, provided to the rodent or human subject. A recent study even shows differences in immunological outcomes between a low fat diet and mice consuming a normal mouse chow. Mice consuming a low fat diet were more susceptible to death from influenza infection compared to mice on a normal chow (75). Therefore, it is essential to avoid confounding results by standardizing treatment regimes in relation to fat composition.

Conclusions

The results across model systems provide evidence that B-cell cytokine secretion and/or antibody production, outside of the context of adipose tissue inflammation, are modulated in obesity. Modifications to B-cell function may be a major contributing factor toward the poor response to infections and vaccinations in the obese. Furthermore, the data show that essential fatty acid status, which is dysregulated in obesity, is an important variable in influencing antibody production in obese mice upon influenza infection, potentially through an SPM-mediated mechanism. This has implications for further investigating intervention strategies with a range of essential fatty acids and D-series SPMs for select clinical populations such as the obese or even the aged that have diminished humoral immunity.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by: NIH R01AT008375 (S.R.S), Brody Brothers Foundation Award (S.R.S), Foundation Award from Caroline Raby (S.R.S), the North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute 550KR51320 (S.R.S.), NIH R01DK096907 (P.D.N), NIH S10RR026522 (N.R.), NIH UL1TR001082 (N.R.), NIH R01AI078090 (M.B.), NIH P30DK056350 (M.B), American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC) (S.S.-C), and NIH NIAID contract HHSN272201400006C (S.S.-C).

Abbreviations: AA, arachidonic acid; BMI, body-mass index; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid, HF, high fat; HAI, hemagglutination inhibition titers; LA, linoleic acid; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; pi, post-infection; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; SPM, specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators; WD, Western diet.

The authors have declared there are no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.McGill HC, McMahan CA, Herderick EE, Zieske AW, Malcom GT, Tracy RE, Strong JP PDAY Research Group. Obesity accelerates the progression of coronary atherosclerosis in young men. Circulation. 2002;105(23):2712–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000018121.67607.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quante M, Dietrich A, ElKhal A, Tullius SG. Obesity-related immune responses and their impact on surgical outcomes. Int J Obes. 2015;39:877–883. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allott EH, Hursting SD. Obesity and cancer: mechanistic insights from transdisciplinary studies. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22(6):R365–R86. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karlsson EA, Beck MA. The burden of obesity on infectious disease. Exp Biol Med. 2010;235(12):1412–24. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y, Nakayama O, Makishima M, Matsuda M, Shimomura I. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(12):1752–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixit VD. Adipose-immune interactions during obesity and caloric restriction: reciprocal mechanisms regulating immunity and health span. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:882–892. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0108028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishra AK, Dubey V, Ghosh AR. Obesity: An overview of possible role(s) of gut hormones, lipid sensing and gut microbiota. Metab Clin Exp. 2016;65:48–65. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee BC, Lee J. Cellular and molecular players in adipose tissue inflammation in the development of obesity-induced insulin resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2014;1842:446–462. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW., Jr Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber DJ, Rutala WA, Samsa GP, Santimaw JE, Lemon SM. Obesity as a predictor of poor antibody response to hepatitis b plasma vaccine. J Am Med Assoc. 1985;254(22):3187–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huttunen R, Syrjanen J. Obesity and the risk and outcome of infection. Int J Obes. 2013;37:333–340. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genoni G, Prodam F, Marolda A, Giglione E, Demarchi I, Bellone S, Bona G. Obesity and infection: two sides of one coin. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;173:25–32. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheridan PA, Paich HA, Handy J, Karlsson EA, Hudgens MG, Sammon AB, Holland LA, Weir S, Noah TL, Beck MA. Obesity is associated with impaired immune response to influenza vaccination in humans. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012;36:1072–1077. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhai X, Qian G, Wang Y, Chen X, Lu J, Zhang Y, Huang Q, Wang Q. Elevated B cell activation is associated with type 2 diabetes development in obese subjects. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;38(3):1257–66. doi: 10.1159/000443073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arai S, Maehara N, Iwamura Y, Honda SI, Nakashima K, Kai T, Ogishi M, Morita K, Kurokawa J, Mori M, et al. Obesity-associated autoantibody production requires AIM to retain the immunoglobulin M immune complex on follicular dendritic cells. Cell Rep. 2013;3(4):1187–98. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milner JJ, Sheridan PA, Karlsson EA, Schultz-Cherry S, Shi Q, MA Diet-induced obese mice exhibit altered heterologous immunity during a secondary 2009 pandemic H1N1 infection. J Immunol. 2013;191(5):2474–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farnsworth CW, Shehatou CT, Maynard R, Nishitani K, Kates SL, Zuscik MJ, Schwarz EM, Daiss JL, Mooney RA. A humoral immune defect distinguishes the response to staphylococcus aureus infections in mice with obesity and type 2 diabetes from that in mice with type 1 diabetes. Infect Immun. 2015;83(6):2264–74. doi: 10.1128/IAI.03074-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothaeusler K, Baumgarth N. B-cell fate decisions following influenza virus infection. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:366–377. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaikh SR, Haas KM, Beck MA, Teague H. The effects of diet-induced obesity on B cell function. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015;179(1):90–9. doi: 10.1111/cei.12444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frasca D, Ferracci F, Diaz A, Romero M, Lechner S, Blomberg BB. Obesity decreases B cell responses in young and elderly individuals. Obesity. 2016;24:615–625. doi: 10.1002/oby.21383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ying W, Tseng A, Chang RC, Wang H, Lin YL, Kanameni S, Brehm T, Morin A, Jones B, Splawn T, Criscitiello M, Golding MC, Bazer FW, Safe S, Zhou B. miR-150 regulates obesity-associated insulin resistance by controlling B cell functions. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20176. doi: 10.1038/srep20176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winer D, Winer S, Shen L, Wadia P, Yantha J, Paltser G, Tsui H, Wu P, Davidson M, Alonso M, Leong H, Glassford A, Caimol M, Kenkel J, Tedder T, McLaughlin T, Miklos D, Dosch HM, Engleman E. B cells promote insulin resistance through modulation of T cells and production of pathogenic IgG antibodies. Nat Med. 2011;17:610–617. doi: 10.1038/nm.2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen L, Yen Chng MH, Alonso MN, Yuan R, Winer DA, Engleman EG. B-1a lymphocytes attenuate insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2014;64(2):593–603. doi: 10.2337/db14-0554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harmon DB, Srikakulapu P, Kaplan JL, Oldham SN, McSkimming C, Garmey JC, Perry HM, Kirby JL, Prohaska TA, Gonen A, et al. Protective role for B-1b B cells and IgM in obesity-associated inflammation, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(4):682–91. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishimura S, Manabe I, Takaki S, Nagasaki M, Otsu M, Yamashita H, Sugita J, Yoshimura K, Eto K, Komuro I, et al. Adipose natural regulatory B cells negatively control adipose tissue inflammation. Cell Metab. 2013;18(5):759–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholas DA, Nikolajczyk BS. B cells shed light on diminished vaccine responses in obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016;24:551. doi: 10.1002/oby.21429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madhumitha H, Mohan V, Kumar NP, Pradeepa R, Babu S, Aravindhan V. Impaired toll-like receptor signalling in peripheral B cells from newly diagnosed type-2 diabetic subjects. Cytokine. 2015;76:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeFuria J, Belkina AC, Jagannathan-Bogdan M, Snyder-Cappione J, Carr JD, Nersesova YR, Markham D, Strissel KJ, Watkins AA, Zhu M, Allen J, Bouchard J, Toraldo G, Jasuja R, Obin MS, McDonnell ME, Apovian C, Denis GV, Nikolajczyk BS. B cells promote inflammation in obesity and type 2 diabetes through regulation of T-cell function and an inflammatory cytokine profile. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:5133–5138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215840110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheridan PA, Paich HA, Handy J, Karlsson EA, Schultz-Cherry S, Hudgens M, Weir S, Noah T, Beck MA. The antibody response to influenza vaccination is not impaired in type 2 diabetics. Vaccine. 2015;33:3306–3313. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calder PC. Marine omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: Effects, mechanisms and clinical relevance. Biochim Biophys Acta - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2015;1851:469–484. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Micallef M, Munro I, Phang M, Garg M. Plasma n-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids are negatively associated with obesity. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:1370–1374. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509382173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu Y, Cai Z, Zheng J, Chen J, Zhang X, Huang XF, Li D. Serum levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids are low in Chinese men with metabolic syndrome, whereas serum levels of saturated fatty acids, zinc, and magnesium are high. Nutr Res. 2012;32:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Albert BB, Derraik JG, Brennan CM, Biggs JB, Smith GC, Garg ML, Cameron-Smith D, Hofman PL, Cutfield WS. Higher omega-3 index is associated with increased insulin sensitivity and more favourable metabolic profile in middle-aged overweight men. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6697. doi: 10.1038/srep06697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teague H, Fhaner CJ, Harris M, Duriancik DM, Reid GE, Shaikh SR. n-3 PUFAs enhance the frequency of murine B-cell subsets and restore the impairment of antibody production to a T-independent antigen in obesity. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:3130–3138. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M042457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gurzell EA, Teague H, Harris M, Clinthorne J, Shaikh SR, Fenton JI. DHA-enriched fish oil targets B cell lipid microdomains and enhances ex vivo and in vivo B cell function. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;93(4):463–70. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0812394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong JY, Kelly H, Cheung CM, Shiu EY, Wu P, Ni MY, Ip DKM, Cowling BJ. Hospitalization fatality risk of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182(4):294–301. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Serhan CN. Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature. 2014;510:92–101. doi: 10.1038/nature13479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buckley CD, Gilroy DW, Serhan CN. Proresolving lipid mediators and mechanisms in the resolution of acute inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teague H, Harris M, Fenton J, Lallemand P, Shewchuk B, Shaikh SR. Eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid ethyl esters differentially enhance B-cell activity in urine obesity. J Lipid Res. 2014;55(7):1420–33. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M049809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bradberry JC, Hilleman DE. Overview of omega-3 fatty acid therapies. P T. 2013;38(11):681–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramon S, Gao F, Serhan CN, Phipps RP. Specialized proresolving mediators enhance human B cell differentiation to antibody-secreting cells. J Immunol. 2012;189(2):1036–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kane DA, Lin CT, Anderson EJ, Kwak HB, Cox JH, Brophy PM, Hickner RC, Neufer PD, Cortright RN. Progesterone increases skeletal muscle mitochondrial H2O2 emission in nonmenopausal women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300(3):E528–E35. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00389.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rockett BD, Harris M, Shaikh SR. High dose of an n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid diet lowers activity of C57BL/6 mice. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2012;86(3):137–40. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karlsson EA, V, Meliopoulos A, Savage C, Livingston B, Mehle A, Schultz-Cherry S. Visualizing real-time influenza virus infection, transmission and protection in ferrets. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6378. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deems R, Buczynski MW, Bowers-Gentry R, Harkewicz R, Dennis EA. Detection and quantitation of eicosanoids via high performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. 2007;432:59–82. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)32003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang Y, Cruickshank C, Armstrong M, Mahaffey S, Reisdorph R, Reisdorph N. New sample preparation approach for mass spectrometry-based profiling of plasma results in improved coverage of metabolome. J Chromatog A. 2013;1300:217–226. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shaikh SR, Rockett BD, Salameh M, Carraway K. Docosahexaenoic acid modifies the clustering and size of lipid rafts and the lateral organization and surface expression of MHC class I of EL4 cells. J Nutr. 2009;139:1632–1639. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.108720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mazzucchelli R, Durum SK. Interleukin-7 receptor expression: intelligent design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:144–154. doi: 10.1038/nri2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goetz CA, I, Harmon R, O’Neil JJ, Burchill MA, Johanns TM, Farrar MA. Restricted STAT5 activation dictates appropriate thymic B versus T cell lineage commitment. J Immunol. 2005;174:7753–7763. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matthias P, Rolink AG. Transcriptional networks in developing and mature B cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:497–508. doi: 10.1038/nri1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shapiro-Shelef M, Lin KI, Savitsky D, Liao J, Calame K. Blimp-1 is required for maintenance of long-lived plasma cells in the bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1471–1476. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oh DY, Talukdar S, Bae EJ, Imamura T, Morinaga H, Fan W, Li P, Lu WJ, Watkins SM, Olefsky JM. GPR120 is an omega-3 fatty acid receptor mediating potent anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing effects. Cell. 2010;142:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garcia-Bates TM, Baglole CJ, Bernard MP, Murant TI, Simpson-Haidaris PJ, Phipps RP. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligands enhance human B cell antibody production and differentiation. J Immunol. 2009;183:6903–6912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramon S, Baker SF, Sahler JM, Kim N, Feldsott EA, Serhan CN, Martínez-Sobrido L, Topham DJ, Phipps RP. The specialized proresolving mediator 17-HDHA enhances the antibody-mediated immune response against influenza virus: A new class of adjuvant? J Immunol. 2014;193:6031–6040. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Colas RA, Shinohara M, Dalli J, Chiang N, Serhan CN. Identification and signature profiles for pro-resolving and inflammatory lipid mediators in human tissue. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;307(1):C39:54. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00024.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Skarke C, Alamuddin N, Lawson JA, Ferguson JF, Reilly MP, FitzGerald GA. Bioactive products formed in humans from fish oils. J Lipid Res. 2015;56(9):1808–20h. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M060392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Landin AM, Blomberg BB. High TNF-alpha levels in resting B cells negatively correlate with their response. Exp Gerontol. 2014;54:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chan ME, Adler BJ, Green DE, Rubin CT. Bone structure and B-cell populations, crippled by obesity, are partially rescued by brief daily exposure to low-magnitude mechanical signals. FASEB J. 2012;26:4855–4863. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-209841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clark MR, Mandal M, Ochiai K, Singh H. Orchestrating B cell lymphopoiesis through interplay of IL-7 receptor and pre-B cell receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:69–80. doi: 10.1038/nri3570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burrows T, Collins CE, Garg ML. Omega-3 index, obesity and insulin resistance in children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6:e532–539. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2010.549489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Balas L, Guichardant M, Durand T, Lagarde M. Confusion between protectin D1 (PD1) and its isomer protectin DX (PDX). An overview on the dihydroxy-docosatrienes described to date. Biochimie. 2014;99:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clària J, Dalli J, Yacoubian S, Gao F, Serhan CN. Resolvin D1 and resolvin D2 govern local inflammatory tone in obese fat. J Immunol. 2012;189:2597–2605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spite M, Clària J, Serhan CN. Resolvins, Specialized proresolving lipid mediators, and their potential roles in metabolic diseases. Cell Metab. 2014;19:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Titos E, Rius B, Lopez-Vicario C, Alcaraz-Quiles J, Garcia-Alonso V, Lopategi A, Dalli J, Lozano JJ, Arroyo V, Delgado S, Serhan CN, Claria J. Signaling and immunoresolving actions of resolvin D1 in inflamed human visceral adipose tissue. J Immunol. 2016;197:3360–3370. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Neuhofer A, Zeyda M, Mascher D, Itariu BK, Murano I, Leitner L, Hochbrugger EE, Fraisl P, Cinti S, Serhan CN, Stulnig TM. Impaired local production of proresolving lipid mediators in obesity and 17-HDHA as a potential treatment for obesity-associated inflammation. Diabetes. 2013;62:1945–1956. doi: 10.2337/db12-0828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tang Y, Zhang MJ, Hellmann J, Kosuri M, Bhatnagar A, Spite M. Proresolution therapy for the treatment of delayed healing of diabetic wounds. Diabetes. 2013;62:618–627. doi: 10.2337/db12-0684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Karlsson EA, Hertz T, Johnson C, Mehle A, Krammer F, Schultz-Cherry S. Obesity outweighs protection conferred by adjuvanted influenza vaccination. mBio. 2016:7. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01144-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morita M, Kuba K, Ichikawa A, Nakayama M, Katahira J, Iwamoto R, Watanebe T, Sakabe S, Daidoji T, Nakamura S, et al. The lipid mediator protectin D1 inhibits influenza virus replication and improves severe influenza. Cell. 2013;153(1):112–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Coulombe F, Jaworska J, Verway M, Tzelepis F, Massoud A, Gillard J, Wong G, Kobinger G, Xing Z, Couture C, Joubert P, Fritz JH, Powell WS, Divangahi M. Targeted prostaglandin E2 inhibition enhances antiviral immunity through induction of type I interferon and apoptosis in macrophages. Immunity. 2014;40(4):554–68. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tam VC, Quehenberger O, Oshansky CM, Suen R, Armando AM, Treuting PM, Thomas PG, Dennis EA, Aderem A. Lipidomic profiling of influenza infection identifies mediators that induce and resolve inflammation. Cell. 2013;154(1):213–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yog R, Barhoumi R, McMurray DN, Chapkin RS. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids suppress mitochondrial translocation to the immunologic synapse and modulate calcium signaling in T cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:5865–5873. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Teague H, Rockett BD, Harris M, Brown DA, Shaikh SR. Dendritic cell activation, phagocytosis and CD69 expression on cognate T cells are suppressed by n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Immunology. 2013;139:386–394. doi: 10.1111/imm.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim N, Ramon S, Thatcher TH, Woeller CF, Sime PJ, Phipps RP. Specialized proresolving mediators (SPMs) inhibit human B-cell IgE production. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46:81–91. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hariri N, Thibault L. High-fat diet-induced obesity in animal models. Nutr Res Rev. 2010;23:270–299. doi: 10.1017/S0954422410000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Milner JJ, Rebeles J, Dhungana S, Stewart DA, Sumner SCJ, Meyers MH, Mancuso P, Beck MA. Obesity increases mortality and modulates the lung metabolome during pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection in mice. J Immunol. 2015;194:4846–4859. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.