Abstract

Importance

Adequate management of menstrual hygiene is taken for granted in affluent countries; however, inadequate menstrual hygiene is a major problem for girls and women in resource-poor countries, which adversely affects the health and development of adolescent girls.

Objective

The aim of this article is to review the current evidence concerning menstrual hygiene management in these settings.

Evidence Acquisition

A PubMed search using MeSH terms was conducted in English, supplemented by hand searching for additional references. Retrieved articles were reviewed, synthesized, and summarized.

Results

Most research to date has described menstrual hygiene knowledge, attitudes, and practices, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Many school-based studies indicate poorer menstrual hygiene among girls in rural areas and those attending public schools. The few studies that have tried to improve or change menstrual hygiene practices provide moderate to strong evidence that targeted interventions do improve menstrual hygiene knowledge and awareness.

Conclusion and Relevance

Challenges to improving menstrual hygiene management include lack of support from teachers (who are frequently male); teasing by peers when accidental menstrual soiling of clothes occurs; poor familial support; lack of cultural acceptance of alternative menstrual products; limited economic resources to purchase supplies; inadequate water and sanitation facilities at school; menstrual cramps, pain, and discomfort; and lengthy travel to and from school, which increases the likelihood of leaks/stains. Areas for future research include the relationship between menarche and school dropout, the relationship between menstrual hygiene management and other health outcomes, and how to increase awareness of menstrual hygiene management among household decision makers including husbands/fathers and in-laws.

Target Audience

Obstetricians and gynecologists, family physicians.

Learning Objectives

After completion of this educational activity, the obstetrician/gynecologist should be able to define what is meant by “adequate menstrual hygiene management,” identify the challenges to adequate menstrual hygiene management that exist in resource-poor countries, and describe some of the intervention strategies that have been proposed to improve menstrual hygiene management for girls and women in those countries.

Menstruation is a normal biological process experienced by millions of women and girls around the world each month. Menarche signifies the start of a female’s reproductive years and often marks her transition to full adult female status within a society. Age at menarche tends to be slightly later in resource-poor countries than in higher-income countries,1 yet an apparent decline in age at menarche has been documented in both developed2,3 and developing countries4 over the past few decades. One challenge of menstruation that is taken for granted in affluent countries is the simple question of how to manage or contain the menstrual flow and what happens to a girl or woman who is not able to do this successfully. The United Nations defines adequate menstrual hygiene management as “women and adolescent girls using a clean menstrual management material to absorb or collect blood that can be changed in privacy as often as necessary for the duration of the menstruation period, using soap and water for washing the body as required, and having access to facilities to dispose of used menstrual management materials.”5 Particularly in poor countries, girls and women face substantial barriers to achieving adequate menstrual management.

Gender equity in education has long been heralded as a cornerstone for social and economic development. The education of girls and women holds a prominent position in both the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals and in the recently adopted Sustainable Development Goals.6 Although much progress has been made since 2000, in many countries (especially in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa) a large number of girls either never attend school or attend only a few years of primary school before dropping out.7 Furthermore, the number of out-of-school girls is rising again after years of improvement.7

Earlier menarche and a greater emphasis on education mean that many adolescent girls are in school while menstruating. With a typical menstrual cycle lasting 25 to 30 days within which bleeding occurs for 4 to 6 days,8 postmenarcheal girls will experience menstrual bleeding on at least some school days every month. Menstrual hygiene management is therefore an increasingly important (yet often unrecognized) issue that is heavily intertwined with girls’ education, empowerment, and social development.

EVIDENCE ACQUISITION AND EXTRACTION

As part of an ongoing program of menstrual hygiene management research and intervention in Ethiopia (www.dignityperiod.org), we carried out a systematic review of the published literature on menstrual hygiene management to understand the current state of knowledge and gaps in evidence surrounding these practices in resource-poor countries. We searched PubMed with the help of a reference librarian for English-language articles published through December 2015 using the MeSH search terms hygiene or menstrual hygiene products and menstruation. The PubMed search included the following: (("Hygiene"[MeSH] OR "Menstrual Hygiene Products"[MeSH]) AND English[lang]) AND ("Menstruation"[MeSH] AND English[lang]) AND (Journal Article[ptyp] AND English[lang]).

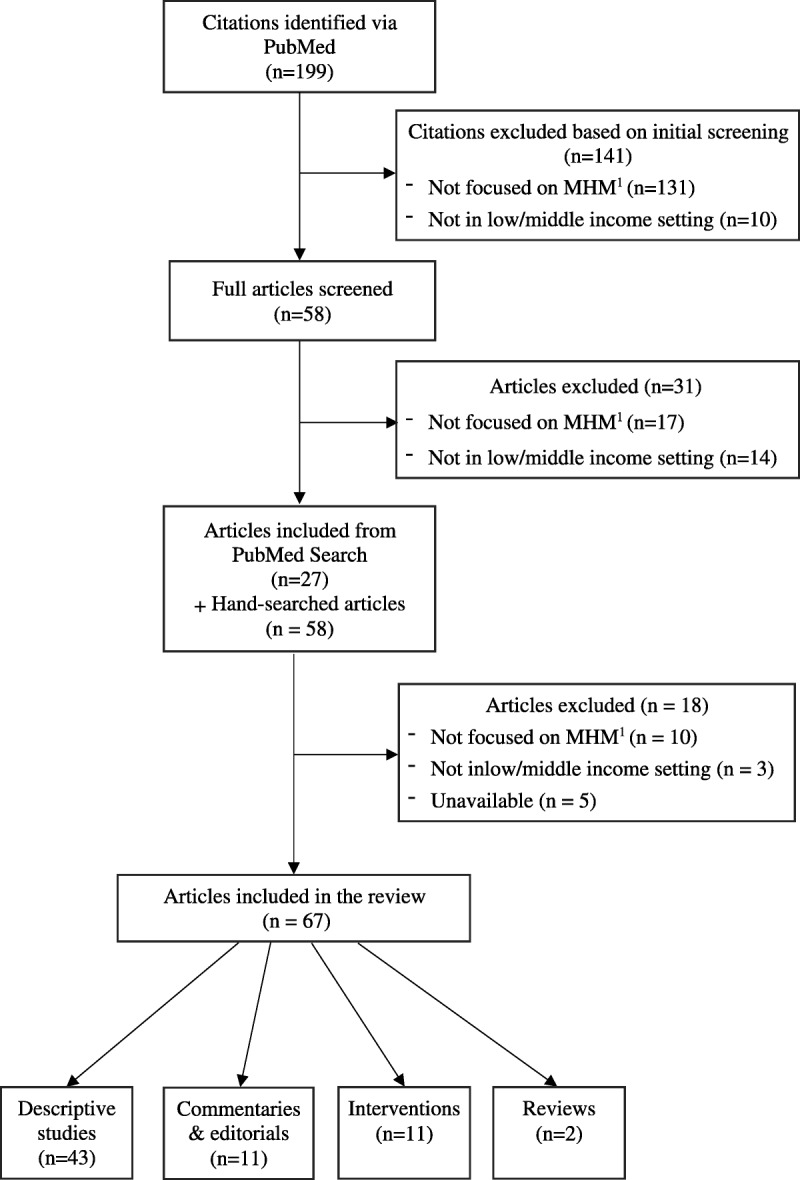

Our electronic search identified 199 unique citations that we then screened for relevance based on title and abstract (Fig. 1). Full-text screening was conducted of 58 articles, of which 27 were retained for inclusion and data extraction. We hand searched the reference lists of these articles plus key background articles to identify an additional 58 citations for screening. From the combined electronic and hand search, we identified 67 articles for inclusion that met the dual criteria of focusing on menstrual hygiene management in the setting of a low- or middle-income country.9 These 67 articles include 43 descriptive studies, 11 intervention evaluation studies, 11 commentaries/editorials, and 2 review articles. For each included article, we extracted essential information into a spreadsheet to facilitate analysis. Extracted information for all articles included bibliographic information, research question or purpose, and information on the setting or location in which it was carried out. For descriptive studies, intervention evaluations, and review articles, we also extracted information on study design, sample characteristics, results, and limitations. We also extracted a description of the intervention that was used in those evaluation studies.

FIG. 1.

Article identification flowchart. MHM, menstrual hygiene management.

THE CURRENT STATUS OF MENSTRUAL HYGIENE MANAGEMENT IN RESOURCE-POOR COUNTRIES

Most of the existing literature is descriptive in nature, explaining menstrual hygiene practices, knowledge, and attitudes—including beliefs and cultural taboos—and where girls get their information about menstruation. There are also observational studies that look at the associations between menstrual hygiene management practices and various sociodemographic and contextual characteristics (eg, lack of privacy, water, and/or proper sanitary disposal at school). Many of these studies are school based and often compare urban versus rural schools and/or private versus public schools. These articles frequently conclude that menstrual hygiene management is worse for girls in rural areas and for those who attend public schools (which tend to serve families of lower socioeconomic status). Studies are heavily concentrated in a handful of sub-Saharan African countries and the South Asia region. Very little is published in English from Latin America, North Africa and the Middle East, or Central Asia. The academic literature has recently been paying more attention to issues surrounding menstrual hygiene management. Only 10 of the 67 articles included in this review were published prior to 2000.

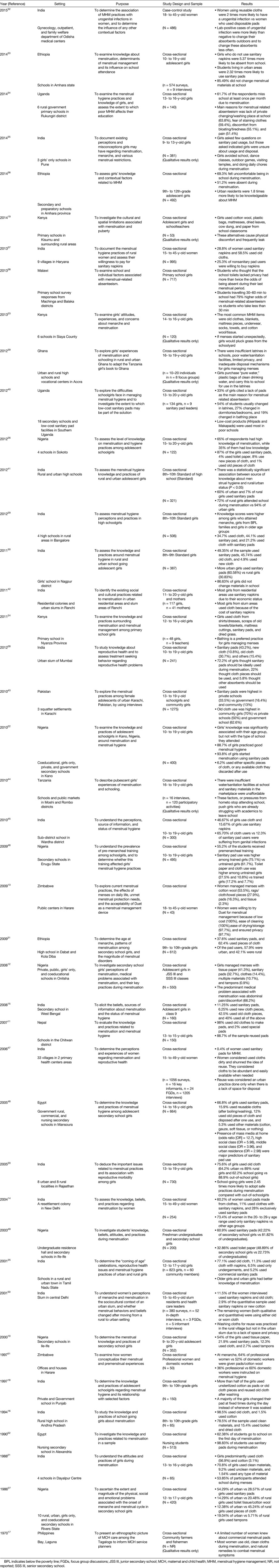

Girls in resource-poor countries around the world tend to use old cloths, tissue paper, cotton or wool pieces, or some combination of these items to manage their menstrual bleeding10–31 (Table 1). Egypt appears to be an exception to this pattern, where a large majority of girls report using commercially produced sanitary pads or napkins instead of homemade menstrual hygiene devices.48,52 Qualitative studies indicate that girls who know about commercial sanitary products may prefer these products because they are seen as more comfortable and less likely to leak, but for many girls such products are usually unavailable and/or unaffordable.13,19,24,40,44

TABLE 1.

Summary Results of Descriptive Articles Included in the Review

Use of commercially produced sanitary pads is reported more commonly among girls in private schools, which typically serve wealthier families43; among those in urban areas41; and among girls who have received explicit training in how to use commercial sanitary products.46 The evidence is mixed, however, from urban slums where some studies report higher use of sanitary pads,28 whereas others report higher use of old cloths.42 Furthermore, knowledge about menstruation and menstrual hygiene tends to be higher in girls from urban areas compared with rural girls25,36,41 and in older as compared with younger adolescent girls.22,25,29

Girls from resource-poor countries around the world attribute frequent school absences to difficulties managing their menses. In a Ugandan study of rural schoolgirls, nearly two-thirds said they miss school at least once per month because of menstruation.34 In India, only 54% of girls reported attending school while menstruating.21 In Egypt, more than one-third of girls in an urban secondary school reported staying home from school on the first day of menstruation.52 Similarly, in Amhara province, Ethiopia, more than half of girls in secondary and preparatory schools reported being absent during menstruation,36 and those who did not use sanitary pads were more than 5 times as likely to be absent.33 Even if girls are not absent and manage to attend school during menstruation, they report being distracted, unable to concentrate, and less willing to participate because, for example, standing to answer questions is the custom in many schools, and writing on a blackboard in front of the class may expose them revealing menstrual stains, leakage, or odors.19,23,24,33,34

Absenteeism appears to be closely associated with lack of privacy and limited availability of water and sanitation facilities at schools. In Malawi, girls who reported that school toilets lacked privacy were more than twice as likely to be absent during their menstrual periods than girls at schools where more privacy was available.38 In Uganda, girls cited a lack of privacy and washing space, fear of leakage and stains, discomfort, and a lack of pads as reasons for school absences during menstruation.34,40 Given the opportunity to design their ideal toilet for school, girls emphasize the need for better lighting in latrines to be able to spot leaks and clean themselves34,40; more privacy including doors on latrines and functioning locks for the doors34,39,44; a water supply within the latrine in order to wash soiled hands, legs, or clothes34,39,44; lack of soap34,39,44 and toilet paper34; and no disinfectant or cleaning supplies to clean latrines after use.39,44

While only a few studies have tested the relationship between infections and the type of material or product used to manage menstrual bleeding, those that have done so suggest that reusing old cloths may increase the risk of urogenital infections. In a case-control study from India, women with urogenital infections were twice as likely to have been using reusable cloths instead of disposable sanitary pads.32 In another study of schoolgirls in India, 65.7% of homemade menstrual cloth users reported urogenital infections compared with only 12.3% of those using sanitary pads.45 Qualitatively, women and girls recognize that the way they manage their menstrual blood may be unhygienic, but they do not have better alternatives. For example, women in Zimbabwe expressed concerns about reusing old cloths and know that ironing or drying the cloths in the sun would be best, but they often avoid doing this because of embarrassment, a desire for secrecy, and/or a lack of electricity or coal to heat an iron.13 Other girls feel they must store or hide cloths in places they know are unhygienic so that they are readily available when they need them.20 Some women also insert newspaper or tissue paper into their vaginas to reduce the chance of menstrual leakage despite their concerns that this might not be safe and that the newspaper ink might cause cancer.13

The qualitative studies provide strikingly insightful information about women’s and girls’ perspectives on menstrual hygiene. These studies complement the evidence from quantitative studies. Girls realize that their menses may lead to school absences or even to their leaving school altogether.35,44 Water and sanitation facilities at school are often so inadequate for menstrual hygiene management that some girls report carrying plastic bags of drinking water to use in the school latrines.39,44 Nonetheless, girls are often highly resourceful at making sanitary “pads” out of whatever materials are available if menses start unexpectedly while they are at school, often resorting to the emergency use of leaves or grass.19,23 These homemade options are often uncomfortable, leak frequently, and cause distress.19 Especially in rural areas, women and girls may not even know about the existence of commercially manufactured sanitary products,17 do not know how to use or dispose of them,35 and/or perceive these products to be unaffordable.44 In India, female residents of urban slums report particular challenges in dealing with their menses. They do not have the space to dispose of soiled cloths or other materials47; neither do they have sufficient privacy to wash and dry used cloths as they would be able to do in rural areas.50 In some cases, girls even report exchanging sex for money so they can purchase commercial sanitary products.19,23

INTERVENTIONS TO IMPROVE MENSTRUAL HYGIENE MANAGEMENT IN RESOURCE-POOR COUNTRIES

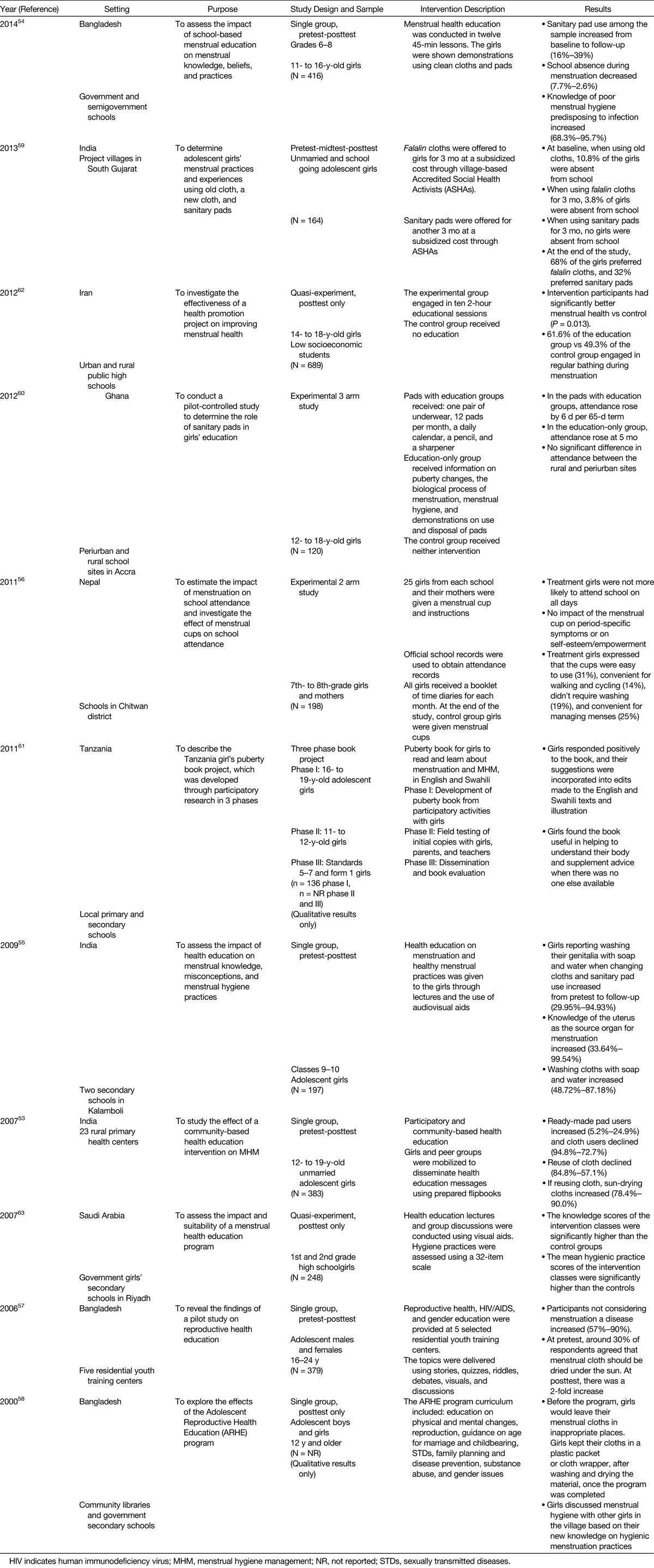

We found only 11 studies evaluating interventions that tried to improve menstrual hygiene management or change menstrual hygiene practices. All of the interventions evaluated have been published since 2000. Seven of these studies were conducted in South Asia,53–59 whereas the other studies were done in Ghana,60 Tanzania,61 Iran,62 and Saudi Arabia63 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Summary Results of Intervention Articles Included in the Review

Nearly all of the interventions were purely educational in nature, most of them taking place in or through the school setting. The 2 quasi-experimental educational interventions both reported better menstrual health62 and hygiene practices63 among the intervention groups. The studies that assessed menstrual hygiene knowledge and practice on a pretest-posttest basis within a single intervention group all reported some improvements, ranging from an increase in knowledge54,57,58 and implementation of hygienic practices (such as drying cloths in the sun and washing with soap and water)53,55 to an increased use of sanitary pads (either disposable or reusable) instead of old homemade cloths.53,54 One study also reported that school absenteeism during menses decreased between the pretest and posttest evaluations.54 Overall, there is moderate evidence that education-based interventions can improve menstrual hygiene knowledge and practices among schoolgirls in resource-poor countries.

The 3 interventions that distributed sanitary products—either pads of various materials59,60 or menstrual cups56—to schoolgirls all evaluated these interventions using quasi-experimental designs. In Ghana, a 3-arm trial showed that both in the pad-with-underwear-distribution-plus-education arm and in the education-only arm attendance improved significantly over the control subjects who received neither pads nor education; however, attendance rose more quickly in the pad-plus-education arm than in the education-only arm of the study.60 In India, an intervention provided schoolgirls with falalin cloth—a short, absorbent, woven cloth—for 3 months, followed by sanitary pads for 3 months. Absenteeism was highest when girls were using old traditional cloths. Absenteeism decreased when falalin cloth was available, but there were no absences among girls when using commercially produced sanitary pads.59 Interestingly, however, a greater proportion of the girls preferred the falalin cloths to the commercial sanitary pads.59 In Nepal, an intervention that distributed menstrual cups to schoolgirls and their mothers in the treatment group and education booklets to all girls failed to find an impact on school attendance. The majority of the girls did not report that the cups were convenient or easy to use.56 There is limited (but mixed) evidence to suggest that distribution of sanitary products may reduce school absenteeism among girls.

The study from Nepal is the only one we found that evaluated outcomes beyond menstrual hygiene management practices and school attendance. This study did not find any effect of the menstrual cup intervention on test scores, cramps, premenstrual symptoms, or self-esteem/empowerment indicators; however, actual use of the menstrual cups within the intervention group was relatively low.56

ADDITIONAL PERSPECTIVES

Eight of the 11 commentaries and editorials on menstrual hygiene management were penned in the last decade, demonstrating how this issue has started to gain prominence. One commentary summarizes a history of menstrual hygiene products,64 and another focuses on differences in menstrual hygiene management between Western nations and other countries, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa.65 Another commentary compares experiences across cultures, albeit between countries in different regions, noting that old cloths and naturally absorbent substances are the most common materials used in menstrual hygiene management, although a few cultures utilize menstrual huts or otherwise exclude women from their usual social interactions during menstruation.66

India and Kenya have received attention over the last few years as these countries have moved to subsidize commercial sanitary products for rural girls and to remove the value-added tax on menstrual hygiene products, respectively. In India, the subsidy plan faces potential pitfalls due to the lack of knowledge and awareness of family members, teachers, and health care providers; lack of water and sanitation facilities available in schools; and lack of sufficient solid-waste disposal in villages.50 Other authors have called attention to the disconnect between focusing on menstrual hygiene management when there is still a serious lack of access to water and sanitation facilities in schools, especially in the South Asia region.67

Sommer68 has written 4 of these commentaries and has become a voice of advocacy for improved menstrual hygiene management for girls in low-resource environments. She has advocated for adding menstrual hygiene management to the agenda of access to clean water and improved sanitation in schools68 and to including menstrual hygiene management as part of the response to humanitarian emergencies.69 She and her colleagues have also argued that menstrual hygiene management should be part of any educational agenda for school-aged girls5 and should be promoted more broadly as a general public health issue.70

The findings from our review are consistent with and expand upon the other review articles that we found on this topic. One review that focused on water and sanitation in schools found that the availability of water and sanitation facilities in schools is a key determinant of girls’ school attendance in general and that lack of such facilities increases the challenges girls face with respect to managing menstrual hygiene.71 Studies included in this review reported that girls often experience discomfort at school during menstruation, have special concerns about privacy when handling menstrual issues, fear teasing from peers (both male and female), lack mechanisms for the proper disposal of menstrual products, and have insufficient water for cleaning themselves while menstruating.71

One other review focused more directly on menstrual hygiene management, but found it difficult to define this term given the variation in definitions used across the included articles.72 Education interventions were found to improve knowledge, awareness, and some menstrual hygiene practices, but documenting the effect of menstrual hygiene management on school attendance and dropout rates is much more difficult, given how poorly records are often kept and the often-ambiguous reasons for school absences.72

We limited our search to peer-reviewed articles published in English. There may be additional interventions reported to improve menstrual hygiene management among adolescent girls in resource-poor countries that have not been published in the peer-reviewed English literature. This may account for the disproportionate number of articles originating from countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In addition, the lack of consistency between studies in terms of how “good” menstrual hygiene management is defined and measured makes it challenging to compare studies and generate accurate summaries. Because menstrual hygiene management is a relatively new (but vitally important) topic for research and advocacy, we expect these definitions and measurements will become more standardized as the field evolves and our understanding of the issue improves.

FUTURE RESEARCH AND ADVOCACY DIRECTIONS

The existing literature on menstrual hygiene management in resource-poor settings highlights common challenges experienced across different cultures. Major barriers to improved menstrual hygiene among girls include a lack of awareness and support from teachers, many of whom are male; lack of familial support; lack of cultural acceptance of certain menstrual hygiene products; limited economic resources to purchase commercially produced products; inadequate water and sanitation facilities at school with concurrent concerns about washing, privacy, and menstrual pad disposal; cramps, pain, and discomfort associated with menstruation irrespective of the menstrual hygiene products used; and travel difficulties to/from school, which can extend time away from home and increase the likelihood of leaks/stains, embarrassment, and discomfort. Fear of embarrassment from menstrual accidents and teasing by peers is a common thread in many qualitative studies.

Our review identified several important gaps in the existing evidence base concerning menstrual hygiene management. First, there is a lack of knowledge around the household decision-making process for school enrollment. How is this decision made for postmenarcheal girls and by whom? What is the level of knowledge and awareness around menstrual hygiene management among those who are making these decisions? We found 1 intervention that targeted menstrual hygiene education at mothers in addition to schoolgirls,56 but we did not find any that also targeted fathers, in-laws, and/or community leaders who might be influential in valuing (or hindering) girls’ access to education. Considering how culturally and religiously embedded beliefs and practices about menstruation are, it is important to understand better the decision-making process for girls’ school enrollment and to extend intervention efforts beyond female relatives only to include all of those involved in the decision-making process. Increasing male understanding of menstruation and the importance of menstrual hygiene management is likely to emerge as a key consideration in improving both school attendance and the availability of suitable water and sanitation facilities at schools in poor countries.

Second, most intervention studies have been school based and focused on the absenteeism of girls who are already enrolled in school. Few studies have looked at girls who are out of school and whether education and awareness efforts with these girls and their families before menarche might reduce the number of girls who drop out around the time menstruation begins. Postmenarcheal girls who are still enrolled in school are likely to be from families who are more supportive of girls’ education. Once a girl drops out of school, getting her reenrolled may be difficult, even if the menstrual hygiene management situation improves.

Third, except for the trial from Nepal that reported low use of provided menstrual cups and few significant findings,56 there are almost no studies looking at outcomes other than absenteeism in schoolgirls. No studies have looked at girls’ school performance or their absenteeism rates with respect to absenteeism among boys. A few qualitative studies identify fear, embarrassment, and pain as important barriers to attending school during menstruation, but these are measured quantitatively less frequently. Other outcomes such as school performance, self-confidence/self-esteem, empowerment, quality of life, and genitourinary infections are almost entirely absent from the reporting. While many of these are culturally constructed and can be difficult to measure, improvements in these areas have the potential to confer important benefits on girls.

Finally, the literature on water and sanitation regarding schools in resource-poor countries is currently disconnected from the literature on menstrual hygiene management. Much of the menstrual hygiene literature mentions the importance of having good access to water and sanitation in schools, but few menstrual hygiene interventions actually attempt to address these issues. Conversely, menstrual hygiene management does not appear to be a significant outcome measure in studies in the literature on water and sanitation. We did not identify a single intervention that tried to improve menstrual hygiene management by focusing on what seems to be the important triad of (1) improved education regarding menstrual hygiene for girls, teachers, parents, and other decision makers; (2) adequate menstrual hygiene supplies; and (3) clean water and improved sanitation in schools. The ability of girls and women to manage their menses hygienically and without disruption of their daily activities is taken for granted in affluent countries. In these countries, access to menstrual hygiene supplies is generally easy and affordable. This is not the case for women and girls in resource-poor countries. We suspect that this is also true in impoverished parts of the United States and other seemingly resource-rich nations. We are learning that poor menstrual hygiene management may have serious health and developmental consequences for adolescent girls. This seems to be an important factor in hindering the education and empowerment of women in the world’s poor countries. Because these issues affect half of the world’s people, they merit increased attention by educators, policy makers, and government officials. Improved menstrual hygiene management needs to be on the health agendas of all resource-poor countries, particularly as those countries strive to train large cadres of teachers and community-based/primary-care health workers.

In the United States and other high-income countries, we must also strive to increase the awareness of the importance of menstrual hygiene management among clinicians so that they can better serve their patients, particularly those who are recent immigrants from resource-poor countries where menstrual hygiene management may be a serious issue. Lack of adequate menstrual hygiene management may also be present in the poorest parts of affluent countries, where access to menstrual supplies is taken for granted and where these problems may easily be overlooked. Clinicians everywhere should be active partners in promoting better access to menstrual hygiene products, better water and sanitation in schools, and better knowledge within local communities concerning the basic biology of menstruation and how to manage the problems that may arise with it. Finally, we seek to make clinical researchers aware of the existing knowledge gaps concerning menstrual hygiene management among the world’s poor, especially gaps in our knowledge concerning the relationship between menstrual hygiene management and health outcomes such as genitourinary infections, healthy social development, and sound mental health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Donghua Tao, reference librarian at Saint Louis University, for her assistance in developing and implementing the search strategy in PubMed.

Footnotes

Dr. Wall has disclosed that he is the President of Dignity Period, a not-for-profit charity in Tigray, Ethiopia. He and his spouse have no financial relationships with, or financial interests in, any commercial organizations pertaining to this educational activity.

The remaining authors, faculty, and staff in a position to control the content of this CME activity and their spouses/life partners (if any) have disclosed that they have no financial relationships with, or financial interests in, any commercial organizations pertaining to this educational activity.

Lippincott CME Institute has identified and resolved all conflicts of interest concerning this educational activity.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thomas F, Renaud F, Benefice E, et al. International variability of ages at menarche and menopause: patterns and main determinants. Hum Biol. 2001;73:271–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDowell MA, Brody DJ, Hughes JP. Has age at menarche changed? Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talma H, Schönbeck Y, van Dommelen P, et al. Trends in menarcheal age between 1955 and 2009 in the Netherlands. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pathak PK, Tripathi N, Subramanian SV. Secular trends in menarcheal age in India—evidence from the Indian human development survey. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sommer M, Sahin M. Overcoming the taboo: advancing the global agenda for menstrual hygiene management for schoolgirls. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1556–1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform [SDG Web site]. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs. Accessed August 12, 2016.

- 7.UNESCO Institute of Statistics. A growing number of children and adolescents are out of school as aid fails to meet the mark [Internet]. Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002336/233610e.pdf. Accessed August 12, 2016.

- 8.Reed BG, Carr BR. The normal menstrual cycle and the control of ovulation. In: de Groot LJ, Beck-Peccoz P, Chrousos G, et al., eds. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups [World Bank Web site]. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups. Accessed August 12, 2016.

- 10.Abioye-Kuteyi EA. Menstrual knowledge and practices amongst secondary school girls in Ile Ife, Nigeria. J R Soc Promot Health. 2000;120:23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adhikari P, Kadel B, Dhungel SI, et al. Knowledge and practice regarding menstrual hygiene in rural adolescent girls of Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2007;5:382–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adinma ED, Adinma JI. Perceptions and practices on menstruation amongst Nigerian secondary school girls. Afr J Reprod Health. 2008;12:74–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Averbach S, Sahin-Hodoglugil N, Musara P, et al. Duet for menstrual protection: a feasibility study in Zimbabwe. Contraception. 2009;79:463–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baridalyne NR, Reddaiah VP. Menstruation knowledge, beliefs and practices of women in the reproductive age group residing in an urban resettlement colony of Delhi. Health Popul Perspect Issues. 2004;27:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dasgupta A, Sarkar M. Menstrual hygiene: how hygienic is the adolescent girl? Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drakshayani DK, Raiah V. A study on menstrual hygiene among rural adolescent girls. Indian J Med Sci. 1994;48:139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iocano FL. Maternal and child care among the Tagalogs in Bay, Laguna, Philippines. Asian Stud. 1970;8:277–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James A. Menstrual hygiene. A study of knowledge and practices. Nurs J India. 1997;88:221–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jewitt S, Ryley H. It’s a girl thing: menstruation, school attendance, spatial mobility and wider gender inequalities in Kenya. Geoforum. 2014;56:137–147. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khanna A, Goyal RS, Bhawsar R. Menstrual practices and reproductive problems: a study of adolescent girls in Rajasthan. J Health Manage. 2005;7:91–107. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar R. KAP of high school girls regarding menstruation in rural area. Health Popul Perspect Issues. 1988;11:96–100. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawan UM, Yusuf NW, Musa AB. Menstruation and menstrual hygiene amongst adolescent school girls in Kano, Northwestern Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010;14:201–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mason L, Nyothach E, Alexander K, et al. ‘We keep it secret so no one should know’—a qualitative study to explore young schoolgirls attitudes and experiences with menstruation in rural western Kenya. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMahon SA, Winch PJ, Caruso BA, et al. ‘The girl with her period is the one to hang her head’. Reflections on menstrual management among schoolgirls in rural Kenya. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2011;11:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narayan KA, Srinivasa DK, Pelto PJ, et al. Puberty rituals, reproductive knowledge and health of adolescent schoolgirls in South India. Asia Pac Popul J. 2001;16:225–238. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oche MO, Umar AS, Gana GJ, et al. Menstrual health: the unmet needs of adolescent girls in Sokoto Nigeria. Sci Res Essays. 2012;7:410–418. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osujih M. Menstruation problems in Nigerian students and sex education. J R Soc Health. 1986;106:219–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prateek B, Saurabh S. A cross sectional study of knowledge and practices about reproductive health among female adolescents in an Urban Slum of Mumbai. J Fam Reprod Health. 2011;5:117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shanbhag D, Shilpa R, D’Souza N, et al. Perceptions regarding menstruation and practices during menstrual cycles among high school going adolescent girls in resource limited settings around Bangalore city, Karnataka, India. Int J Collab Res Intern Med Public Health. 2012;4:1353–1362. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thakre SB, Thakre SS, Reddy M, et al. Menstrual hygiene: knowledge and practice among adolescent school girls of Saoner, Nagpur District. J Clin Diagn Res. 2011;5:1027–1033. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zegeye DT, Megabiaw B, Mulu A. Age at menarche and the menstrual pattern of secondary school adolescents in northwest Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health. 2009;9:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das P, Baker KK, Dutta A, et al. Menstrual hygiene practices, WASH access and the risk of urogenital infection in women from Odisha, India. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tegegne TK, Sisay MM. Menstrual hygiene management and school absenteeismamong female adolescent students in Northeast Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boosey R, Prestwich G, Deave T. Menstrual hygiene management amongst schoolgirls in the Rukungiri district of Uganda and the impact on their education: a cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;19:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chothe V, Khubchandani J, Seabert D, et al. Students’ perceptions and doubts about menstruation in developing countries: a case study from India. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15:319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gultie T, Hailu D, Workineh Y. Age of menarche and knowledge about menstrual hygiene management among adolescent school girls in Amhara province, Ethiopia: implication to health care workers & school teachers. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Misra P, Upadhyay RP, Sharma V, et al. A community-based study of menstrual hygiene practices and willingness to pay for sanitary napkins among women of a rural community in northern India. Natl Med J India. 2013;26:335–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grant MJ, Lloyd CB, Mensch BS. Menstruation and school absenteeism: evidence from rural Malawi. Comp Educ Rev. 2013;57:260–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sommer M, Ackatia-Armah NM. The gendered nature of schooling in Ghana: hurdles to girls’ menstrual management in school. J Cult Afr Women Stud. 2012;20:63–79. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crofts T, Fisher J. Menstrual hygiene in Ugandan schools: an investigation of low-cost sanitary pads. J Water Sanitation Hyg Dev. 2012;2:50–58. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salve SB, Dase RK, Mahajan SM, et al. Assessment of knowledge and practices about menstrual hygiene amongst rural and urban adolescent girls—a comparative study. Int J Recent Trends Sci Technol. 2012;3:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar A, Srivastava K. Cultural and social practices regarding menstruation among adolescent girls. Soc Work Public Health. 2011;26:594–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ali TS, Rizvi SN. Menstrual knowledge and practices of female adolescents in urban Karachi, Pakistan. J Adolesc. 2010;33: 531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sommer M. Where the education system and women’s bodies collide: the social and health impact of girls’ experiences of menstruation and schooling in Tanzania. J Adolesc. 2010;33: 521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mudey AB, Kesharwani N, Mudey GA, et al. A cross-sectional study on awareness regarding safe and hygienic practices amongst school going adolescent girls in rural area of Wardha District, India. Global J Health Sci. 2010;2:225–231. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aniebue UU, Aniebue PN, Nwankwo TO. The impact of pre-menarcheal training on menstrual practices and hygiene of Nigerian school girls. Pan Afr Med J. 2009;2:9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh AJ. Place of menstruation in the reproductive lives of women of rural North India. Indian J Community Med. 2006;31:10–14. [Google Scholar]

- 48.El-Gilany AH, Badawi K, El-Fedawy S. Menstrual hygiene among adolescent schoolgirls in Mansoura, Egypt. Reprod Health Matters. 2005;13:147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Irinoye OO, Ogungbemi A, Ojo AO. Menstruation: knowledge, attitude and practices of students in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2003;12:43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garg R, Goyal S, Gupta S. India moves towards menstrual hygiene: subsidized sanitary napkins for rural adolescent girls-issues and challenges. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16: 767–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McMaster J, Cormie K, Pitts M. Menstrual and premenstrual experiences of women in a developing country. Health Care Women Int. 1997;18:533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.el-Shazly MK, Hassanein MH, Ibrahim AG, et al. Knowledge about menstruation and practices of nursing students affiliated to University of Alexandria. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 1990;65:509–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dongre AR, Deshmukh PR, Garg BS. The effect of community-based health education intervention on management of menstrual hygiene among rural Indian adolescent girls. World Health Popul. 2007;9:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haque SE, Rahman M, Itsuko K, et al. The effect of a school-based educational intervention on menstrual health: an intervention study among adolescent girls in Bangladesh. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nemade D, Anjenaya S, Gujar R. Impact of health education on knowledge and practices about menstruation among adolescent school girls of Kalamboli, Navi-Mumbai. Health Popul Perspect Issues. 2009;32:167–175. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oster E, Thorton R. Menstruation, sanitary products, and school attendance: evidence from a randomized evaluation. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2011;3:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rahman L, Rob U, Bhuiya I, et al. Achieving the Cairo Conference (ICPD) goal for youth in Bangladesh. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2005;24:267–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rashid SF. Providing sex education to adolescents in rural Bangladesh: experiences from BRAC. Gend Dev. 2000;8: 28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shah SP, Nair R, Shah PP, et al. Improving quality of life with new menstrual hygiene practices among adolescent tribal girls in rural Gujarat, India. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21:205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Montgomery P, Ryus CR, Dolan CS, et al. Sanitary pad interventions for girls’ education in Ghana: a pilot study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sommer M. An early window of opportunity for promoting girls’ health: policy implications of the girl’s puberty book project in Tanzania. Int Electron J Health Educ. 2011;14:77–92. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fakhri M, Hamzehgardeshi Z, Hajikhani Golchin NA, et al. Promoting menstrual health among persian adolescent girls from low socioeconomic backgrounds: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fetohy EM. Impact of a health education program for secondary school Saudi girls about menstruation at Riyadh City. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2007;82:105–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jones IH. Menstruation: the history of sanitary protection. Nurs Times. 1980;76:407–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moseley S. Practical protection. Nurs Stand. 2008;23:24–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Milligan A. Nursing Aid. Lifting the curse. Nurs Times. 1987;83:50–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mahon T, Fernandes M. Menstrual hygiene in South Asia: a neglected issue for WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) programs. Gend Dev. 2010;18:99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sommer M. Putting “menstrual hygiene management” into the school water and sanitation agenda. Waterlines. 2010;29:268–278. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sommer M. Menstrual hygiene management in humanitarian emergencies: gaps and recommendations. Waterlines. 2012;31:83–104. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sommer M, Hirsch JS, Nathanson C, et al. Comfortably, safely, and without shame: defining menstrual hygiene management as a public health issue. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1302–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jasper C, Le TT, Bartram J. Water and sanitation in schools: a systematic review of the health and educational outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:2772–2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sumpter C, Torondel B. A systematic review of the health and social effects of menstrual hygiene management. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]