Abstract

Fibrotic remodeling is a hallmark of most forms of cardiovascular disease and a strong prognostic indicator of the advancement towards heart failure. Myofibroblasts, which are a heterogeneous cell-type specialized for extracellular matrix (ECM) secretion and tissue contraction, are the primary effectors of the heart’s fibrotic response. This review is focused on defining myofibroblast physiology, its progenitor cell populations, and the core signaling network that orchestrates myofibroblast differentiation as a way of understanding the basic determinants of fibrotic disease in the heart and other tissues.

Keywords: Myofibroblast, Fibrosis, Differentiation, Actin Cytoskeleton, TGFβ, Mitogen Activated Protein Kinases, TRP Channels, RNA Binding Proteins

1. Introduction

Fibrosis is a hallmark of heart disease independent of its etiology. Managing cardiac fibrosis is a major clinical concern given its correlation to a heightened risk of ventricular arrhythmias, sudden cardiac death, and rapid progression towards failure [1-4]. After an ischemic insult or myocardial infarction fibrotic remodeling is a critical phase of physiologic wound healing because the enhanced secretion of ECM structurally supports the injured myocardium. However, permanent fibrotic scarring ensues due to the heart’s limited regenerative capacity. Similarly, with chronic injury that is associated with hypertension, aging, diabetes, or primary genetic disease, fibrotic matrix accumulates in perivascular and interstitial spaces without myocyte necrosis and further impairs myocardial function.

Decades of work have identified the myofibroblast as the major cellular effector of the fibrotic response [5-8]. To date research in the fibrosis field is dominated by studies from in vitro experimentation. However, the development of multi-dimensional biomaterials for cell culture studies that better mimic a tissue’s microenvironment makes it clear that physical surroundings markedly influence the molecular determinants of a myofibroblast precursor cell’s fate [9-13]. Moreover, new fate mapping strategies have evolved that allow a deeper understanding of the complexities of identifying myofibroblast phenotypes and the regulatory networks governing this process. Together these factors likely contribute to the plethora of confounding data regarding key molecular pathways and cell populations responsible for fibrosis. Hence, this review places special emphasis on curating these data into a refined molecular signaling network based on in vivo validation as well as emphasized genetic fate mapping efforts as a means of understanding how cellular heterogeneity impacts myofibroblast function and hence fibrotic outcomes in response to various cardiac injuries.

2. The Myofibroblast Identity

2.1 Characteristics of the Myofibroblast

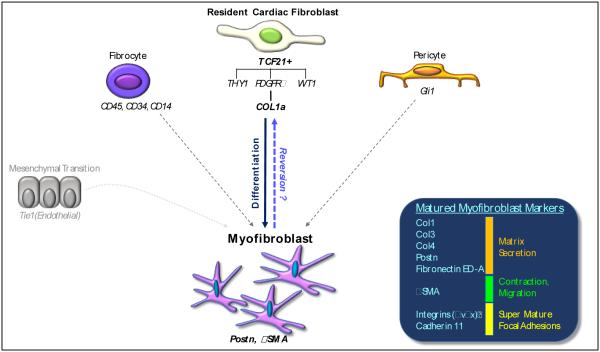

Myofibroblasts are typically found in the interstitium of the injured heart with spindle shaped appearance, dendritic processes, and expanded golgi and endoplasmic reticulum organelles. Contractile bodies in myofibroblasts are electron dense and contain embryonic smooth muscle myosin and α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) [14]. Occasionally alternative skeletal myosin isoforms have also been detected in myofibroblasts [15]. The emergence of αSMA stress fibers is the primary marker for a fully matured myofibroblast, and αSMA underlies the ability of the myofibroblast to contract, migrate, and impart traction forces onto the ECM. Along with acquiring contractile function, myofibroblasts can secrete large amounts of matrix specialized for reinforcing the structural integrity of the heart including variants of Collagen 1 (Col1a1), Collagen 3, Collagen 4, Periostin (Postn), and Fibronectin (Figure 1). During the activation process TGFβ initiates the incorporation of the ED-A splice variant into the matrix, which in is required for both latent TGFβ activation and the incorporation of αSMA into stress fibers that together creates a feed-forward loop for reinforcing the myofibroblast phenotype [16-18]. Indeed, mice lacking the ED-A variant have reduced numbers of αSMA+ myofibroblasts and fibrosis after myocardial infarction [19].

Figure 1.

Cellular progenitors of cardiac myofibroblasts. Fate mapping approaches have identified that locally residing TCF21 positive epicardially derived fibroblasts are responsible for the majority of myofibroblasts that secrete collagen (Col1a) and periosten (Postn) and express αSMA. A majority of TCF21 fibroblasts are also positive for PDGFRα and can also express THY1 and/or WT1. Circulating fibrocytes that are hematopoietic (CD45+, CD34+, CD14+) and GLI1+ pericytes can also give rise to myofibroblasts in the heart, but their contribution to the myofibroblast population seems to be primarily associated with ischemic injury. Endothelial and epithial to mesenchymal transition has also been proposes as a mechanism for myofibroblast formation although recent studies suggest that less than 5% of Col1a+ myofibroblasts come from this population in response to aortic banding.

Myofibroblasts physically connect to the ECM through integrins that are linked to highly developed focal adhesions. These focal adhesions are 4-5 times longer than those observed in quiescent fibroblasts [20]. Increased expression of factors like αvβ3 or αvβ5 integrin, cadherin 11, vinculin, tensin, paxillin, and activated focal adhesion kinase (FAK) can also be used to discriminate between myofibroblast and other cell types [10, 20, 21]. Myofibroblast maturation is marked by the appearance of “supermature” focal adhesions in tandem with αSMA incorporation into stress fibers [10, 20, 21]. The dual expression of these two structures in a myofibroblasts sustains contractile tension, which potentiates wound closure [20]. These unique functional properties can be quantified with various mechanical assays or by assessing wound closure rates in vivo [18, 20, 22].

Myofibroblast differentiation goes through multiple stages in which intermediate phenotypes or proto-myofibroblasts form. At this stage stress fibers containing β-cytoplasmic actin, rather than αSMA, appear with underdeveloped focal adhesions [10]. Proto-myofibroblasts, while structurally immature, synthesize new matrix components like fibronectin ED-A, which are necessary for the final transition into the fully differentiated state [6, 7]. To date signals that mature proto-myofibroblasts and the relative contribution of mature versus immature myofibroblast to fibrotic remodeling has not been defined. Moreover, the challenge of defining the cellular underpinnings of fibrosis is surely impacted by the coexistence of both immature and mature myofibroblasts.

2.2 Sources of the Myofibroblast

Healthy tissue is normally devoid of myofibroblasts, but injury or stress induces their appearance. Diverse sources of cardiac myofibroblasts have been proposed including: locally residing fibroblasts [23-27], circulating fibrocytes of a hematopoietic lineages [5, 28-32], and tissue resident cells undergoing endothelial (EndoMT) or epithelial (EMT) to mesenchymal transition (Figure 1) [33-35]. As we discuss the data for these sources below, it is important to note several limitations to fate mapping studies of fibroblasts. First, all of these cells are derived from multiple developmental sources, and thus they carry many markers that might be passed down to myofibroblast such as: TCF21 (POD1 or Epicardin), platelet-derived growth factor α receptor (PDGRα), thymus antigen 1 (THY1, CD-90), Wilm’s tumor gene 1 (WT1). However, many of these factors fail to extensively mark or solely identify the heart’s fibroblast population [23-27]. For instance, after aortic banding only a small fraction of WT1+ fibroblasts co-label with Col1a and even more rarely with αSMA [26, 36]. Similarly, THY1+ fibroblasts can co-express Col1a, but again only a fraction become αSMA positive in response to hypertensive injury suggesting that these cells rarely differentiate into myofibroblasts at least in response to pressure overload (Figure 1) [24, 26]. There is still another fibroblast population labeled by Col1a, PDGFRα, in addition to TCF21, which is a transcription factor required for ventricular fibroblast development that robustly marks a majority of ventricular fibroblasts in the adult heart [23].

Given this genetic diversity, uniformly labeling mature myofibroblasts is extremely challenging. Col1a has been used extensively to mark both quiescent and activated (myofibroblast) cardiac fibroblast populations [23-25, 37]. However, with pressure overload only 15% of Col1a+ fibroblasts fully matured into αSMA+ myofibroblasts indicating that a hypertrophic stimulus only mildly induces myofibroblast differentiation or another myofibroblast precursor may exist that is not labeled by Col1a [24]. To overcome this limitation, several labs use the matricellular protein periostin (Postn) (Figure 1) [38]. Postn is vital for the development and organization of the ECM and is a hallmark of myofibroblast differentiation [38, 39]. During embryonic development Postn is strongly expressed in cardiac fibroblasts from the TCF21 lineage as well as in some of the valves [38]. With the transition to adulthood Postn is expressed in the periosteum, periodontal ligament, metastatic cancer cells, cells undergoing mesenchymal transition, injured valves, and ~10% of quiescent cardiac fibroblasts [25, 38, 40]. In areas of injury, Postn is robustly expressed in cardiac fibroblasts [25, 41, 42] and corresponds with conversion to a myofibroblast phenotype [22, 41, 43]. Postn-Cre transgenic mice have been extensively used in several organs including the heart to either label or manipulate myofibroblast genes [25, 38, 40, 43-45].

Despite the strong indication that resident fibroblasts are the primary source for myofibroblasts [23-27], there is evidence that other cells contribute to the myofibroblast pool. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition was implicated in contributing to both development and injury repair in the heart [34], although recent studies by independent labs indicate that <5% of myofibroblasts come from this mechanism during pressure overload (Figure 1) [23-26]. Bone-marrow derived circulating fibrocytes can also adopt characteristics of the myofibroblast in response to ischemia-reperfusion injury [31, 46]. These cells retain the hematopoietic markers CD45, CD34 and CD14 while taking on myofibroblast characteristics. Lineage-traced bone marrow transplant studies confirmed bone marrow as a source for myofibroblast-like cells in ischemic injury and a neurohumoral overload models of fibrosis [29]. By contrast transplantation-parabiosis studies indicated hematopoietic fibrocytes do not contribute to the myofibroblast population following pressure overload [26].

As perivascular fibrosis is commonly observed with many cardiac diseases including hypertension, myocarditis and ischemia, many groups have sought out a source for myofibroblasts in the perivascular niche. Pericytes are located near the endothelial basement membrane and express chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (NG2) and PDGFRα. These cells act as a support structure for the endothelium in the vasculature. Pericytes have been associated with fibrosis in the kidney, lungs, and liver (stellate cells) [47, 48]. In the heart, direct expansion of pericytes into myofibroblasts was shown in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy [47]. Recently glioma associated oncogene-1 (Gli1) was found as a marker of resident perivascular stem cells in kidney, lung, liver, and heart (Figure 1) [48]. After pressure overload injury Gli1+ cells differentiated into αSMA+ myofibroblasts that were causal for fibrosis. In this same model fibrogenesis was blocked by ablating Gli1+ cells; providing convincing evidence that this population contributes fibrotic remodeling in hypertensive injury.

As is clear from the data described above the mixed developmental origins of fibroblast presents a huge hurdle for singularly targeting cardiac fibroblasts in vivo. This is reminiscent of the heterogeneity described in fibroblasts populations of other organs like the skin where fibroblasts isolated from various anatomical locations have distinct genetic profiles [49]. Furthermore, we have yet to understand how the genetic profile of myofibroblast progenitors change during differentiation, how genetic heterogeneity affects myofibroblast function, and whether specific types of injury recruit particular populations.

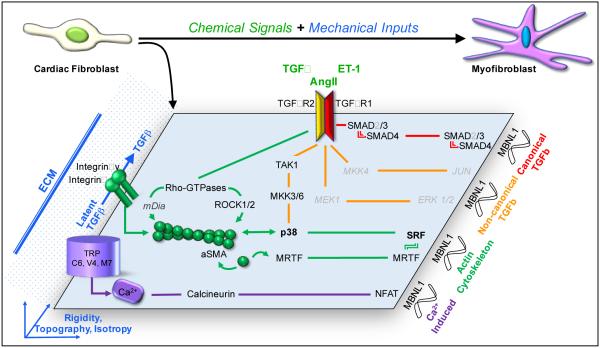

3. The Myofibroblast Differentiation Regulatory Network

The injured myocardium is extremely dynamic as the cellular, chemical, and mechanical milieu fluctuates with the stages of wound healing. These environmental changes activate the programed differentiation of resident fibroblasts into myofibroblasts (Figure 2). Their appearance is triggered by several cytokines, chemokines, neurohumoral factors, and vasoactive peptides circulating throughout the injured environment. These chemical signals include profibrotic (TGFβ) and inflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL-1 and IL-6), as well as the heart failure hormones angiotensin II (AngII) and endothelin-1 (ET-1). The changing mechanical environment also induces fibroblasts to differentiate. To date researchers are still trying to discover how these environmental signals are integrated within the fibroblast and transduced into the differentiation and persistence of myofibroblasts in the heart. Our current knowledge these mechanisms fall under 4 fundamental signaling branches of a regulatory network that are reviewed below and illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The signaling network orchestrating fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation. Injury-induced chemical (TGFβ, AngII, ET-1 and others) and mechanical stimuli (tissue rigidity, shear and tensile forces, and matrix isotropy) activate 4 potent signaling axes: canonical TGFβ (red), non-canonical TGFβ-MAPK (orange), actin cytoskelal (green), and Ca2+-pathways (purple) to induce myofibroblast gene transcription. MBNL1 selectively matures transcripts of the myofibroblast differentiation transcriptome including most components of all 4 axes listed above. Several signaling arms converge on p38 and the transcription factor SRF, suggesting their nodal role in this differentiation process. The combinatorial activation of these regulators potentiate and reinforce the transition of a fibroblast into a myofibroblast. *Factors in gray have links to these pathways but have not been directly proven as regulators myofibroblast conversion.

3.1 Canonical and Non-canonical TGFβ Signaling

TGFβ and its downstream effectors encompass one of the most potent regulatory cascades of myofibroblast differentiation and the fibrotic response. Several cell populations including fibroblasts, inflammatory cells, and resident mesenchymal cells, contribute to the enhanced levels of extracellular TGFβ after an injury. Typically, cells secrete TGFβ in its latent form where it pools in the matrix and becomes activated by enzymatic cleavage events or through mechanical liberation [50]. With injury the heart attains a level of stiffness necessary for activating TGFβ prior to incorporating αSMA into the actin cytoskeleton of differentiating myofibroblasts [20]. This mechanism creates a positive feedback loop that maintains TGFβ in its active state thereby reinforcing the differentiation signal. There are 3 TGFβ ligands; however, TGFβ1 is the most highly studied in the context of fibrosis. Indeed silencing of TGFβ receptor type 1 (TGFβR1) blocks myofibroblast differentiation in vitro [22]. TGFβ1 binds to its heteromeric receptor made up of TGFβ receptor type 1 (TGFβR1) and 2 (TGFβR2), which activate canonical SMAD or non-canonical signaling cascades [51]. In the canonical pathway SMAD2/3 is phosphorylated by TGFβR1, which permits complex formation with SMAD4 and and the transcription of myofibroblast target genes. There’s growing evidence in the literature to suggest that SMAD2 is not a mediator of cardiac fibrosis [52, 53]; whereas, SMAD3 regulates of the secretory phenotype of myofibroblasts including the following ECM genes: Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a1, Col5a2, Col6a1, Col6a3, Fibronectin and TIMP-1 [54]. Furthermore, adenoviral overexpression of inhibitory SMADS 6 and 7,which are specific to canonical SMAD 2/3 signaling, fails to block TGFβ-dependent αSMA stress fiber formation in isolated cardiac fibroblasts [22]. These data are consistent with the attenuated fibrotic scarring observed in heart in SMAD3 knockout mice after myocardial infarction without a decrease in αSMA+ myofibroblast numbers [54]. However, the αSMA promoter contains SMAD3 binding sites and TGFβ response elements suggesting that SMAD signaling regulates the transition to a contractile αSMA+ myofibroblast. In vitro SMAD3 deficient fibroblasts fail to form αSMA-stress fibers, contract, or migrate in response to TGFβ [54], and recent in vivo evidence has demonstrated that fibroblast-specific loss of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) hyper-activates SMAD3 signaling causing cardiac fibroblasts to become αSMA+ and promote fibrotic scar expansion [55]. Moreover, this phenotype could be blocked by treating these mice with small molecule inhibitors of SMAD3 [55] supporting the notion that SMAD3 is involved either directly or indirectly with regulating several features of the myofibroblast phenotype.

Non-canonical TGFβ signaling, which works through activated TGFβR2 (rather than 1 [56-59]) has also been strongly implicated as a regulator of myofibroblast differentiation [60]. TGFβR2 recruits intermediate factors that turn on several downstream signaling cascades including mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), Rho-GTPase-Actin, phosphoinostitide 3 kinase (PI3K) / protein kinase B (PKB or AKT), and TNF Receptor-Associated Factor (TRAF) 4 and 6 [60]. The best characterized non-canonical pathways for myofibroblast differentiation are activated downstream by TGFβ receptor kinase 1 (TAK1), which phosphorylates several intermediate MAPKs and then activates p38 or c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling [22, 61-68]. Using alternative signaling intermediates, TGFβR2 can also induce classical MAPK-extracellular related kinase (ERK) or Rho-GTPase-actin cytoskeletal signaling. While not tested directly in the cardiac fibroblast, activating TAK1 in the heart exacerbates cardiac hypertrophy and induces fulminant interstitial fibrosis [69, 70]; whereas, genetic ablation of TGFβR2 does the opposite in a pressure overload model underscoring the importance of non-canonical TGFβ signaling to cardiac remodeling [56]. Dual specificity MAPK Kinases 3 and 6 (MKK3 and MKK6) transduce the signal from TAK1 to p38, and in kidney fibroblasts TAK1 overexpression activated MKK3 and p38 resulting in enhanced ECM gene expression [71, 72]. By contrast the expression of a dominant negative TAK1 mutant or genetic ablation of MKK3 reduced p38 activity causing a down-regulation of collagen genes [71]. While markers for the fully matured myofibroblast were not examined in these studies, expressing constitutively active variants of MKK6 or p38 in rodent fibroblasts induces αSMA transcriptional activity and αSMA+ stress fibers [22, 68]. Notably, MKK6-mediated myofibroblast differentiation occurs independent of TGFβR1 activity demonstrating that the MKK6-p38 signals reside downstream of the TGFβ receptor [22]. More proximal targeting of the p38 pathway has been performed using specific pharmacologic inhibitors of p38 itself. This strategy dramatically blocked the fibrotic response in injured hearts, lung and kidneys coinciding with a reduction in both collagen and αSMA immunoreactivity [65, 73, 74]. Moreover, p38 inhibition in cardiac fibroblasts or genetic ablation of MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MK2), which is a downstream target of p38 blocked αSMA stress fiber formation, suggesting that p38-mediated myofibroblast transformation is causal for the fibrotic response [22]. However, bleomycin-induced lung injury in MK2 knockout mice causes a fulminant fibrotic response in the absence of αSMA+ myofibroblasts. In this case MK2 regulated contractility and motility through αSMA+ stress fiber formation [75, 76]. These data indicate that various p38 targets modulate select phenotypic characteristics and underscore that the components of these molecular networks likely control independent myofibroblast functions. To date we do not fully understand how myofibroblast contractility and ECM secretion independently alter wound healing and fibrosis, or the ramifications of singularly blocking one function or the other. Because TGFβ signaling is not confined to SMAD-dependent or MAPK signaling, many other pathways and their interactions have yet to be explored with respect to myofibroblast differentiation and the heart’s fibrotic response. The dynamic interplay between these pathways and their temporal activation will ultimately determine the fibroblast’s differentiated state.

3.2 Ca2+-dependent Signaling

There is a growing list of transient receptor potential (TRP) cation channels associated with cellular differentiation including the conversion of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. These channels are part of a family composed of several subtypes that include the following classifications: TRPC (canonical), TRPM (melastatin) TRPV (vanilloid), TRPP (polycystin), TRPA (Ankyrin), and TRPML (mucolipin). Most of the TRP channels are activated by a variety of ligands, the mechanical environment, and/or changes in internal Ca2+ stores. Three different laboratories have demonstrated that cardiac fibroblasts utilize a Ca2+ signal from these channels to transform quiescent fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Of those channels TRPM7, TRPV4, and TRPC6 have been linked to myofibroblast differentiation. TRPM7 appears to be highly specific to human atrial fibroblasts where it represents the dominant source of Ca2+ initiated during TGFβ-dependent myofibroblast differentiation [77]. TRPV4 appears to act as a mechanosensor in ventricular fibroblasts as loss of TRPV4-mediated Ca2+ entry blocked TGFβ and tension-dependent myofibroblast transformation [78]. These particular TRP channel mechanisms have not been tested in the intact heart, but TRPV4 deficient lungs fail to fibrose in response to toxi stimuli like bleomycin [79]. Moreover, loss of TRPV4 in this lung injury model impaired actin cytoskeletal reorganization suggesting that fibroblasts failed to activate and transform.

TRPC6 was identified in a genome-wide screen for regulators of fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation [22]. This result was validated in cardiac fibroblasts by overexpressing TRPC6 and several other TRPC channels [22]. Interestingly, TRPC6 alone was the only TRPC channel that robustly induced both myofibroblast target gene expression (αSMA, fibronectin ED-A, periostin, and Col1a) and contractile activity [22]. These phenotypic changes were absent or extremely weak with the overexpression of other TRPC family members suggesting that TRPC6 has unique properties beyond Ca2+ entry that may facilitate myofibroblast differentiation. Moreover, fibroblasts derived from TRPC6 null mice were unable to differentiate when stimulated with various profibrotic agonists including TGFβ and AngII demonstrating a requirement for TRPC6 in this process [22]. These agonists through a p38 mechanism cause a coordinated increase in TRPC6 gene expression and store-operated Ca2+ entry, which is absent in TRPC6 null fibroblasts explaining their impaired ability to differentiate [22]. Accordingly, TRPC6 null mice have poor dermal wound healing and high mortality rates post myocardial infarction due to reduced matrix deposition and a lack of differentiated myofibroblasts [22].

TRP channels create spatially discrete microenvironments with distinct Ca2+-dependent signaling [80]. Several potent signaling factors have been associated with TRP channels including Rho-GTPase, protein kinase C, receptor for activated C kinase-1, calmodulin, and calcineurin. Calcineurin signaling via nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) is the predominant pathway regulating fibroblast differentiation by TRPC6. This was proven independently by genetic ablation of calcineurin activity, overexpressing genetic calcineurin-NFAT inhibitors, and treatments with pharmacologic inhibitors of calcineurin activity like cylosporin-A (CSA) and FK506, which all impaired matrix formation, αSMA transcription, and antagonized TRPC6-dependent myofibroblast transformation. In the converse experiment expressing constitutively active calcineurin variants in fibroblasts converted them into myofibroblasts independent of a Ca2+ signal. NFAT’s role in myofibroblast differentiation is further supported by data demonstrating that TGFβ induces its nuclear translocation in fibroblasts from several sources and its requirement for pulmonary myofibroblast contraction [15, 22]. These data suggest that NFAT alone is capable of initiating the transcriptional cascade causal for the myofibroblast phenotype at least in vitro. More striking evidence of the impact of the TRPC6-Calcineurin-NFAT signaling axis was observed in vivo as the topical delivery of adenovirus expressing constitutively active calcineurin rescued the poor dermal wound healing of TRPC6 null animals [22]. Together these data demonstrate that TRPC6-Calcineurin-NFAT signaling is a critical branch of the molecular network governing myofibroblast differentiation. Ca2+-sensitive signaling mechanisms are just now being rigorously explored with respect to the fibrotic response in vivo and elucidating Ca2+-transcriptional coupling in myofibroblast progenitors could provide exciting new pathways for modulating fibrosis.

3.3 Actin Cytoskeleton & Mechanotransduction Mechanisms

Fibroblasts are highly sensitive to the physical stimuli present in their microenvironment. Changes in tissue rigidity, shear forces, and strains are mechanical cues sensed by fibroblasts and transduced into new phenotypes. For instance, fibroblasts cultured on silicone membranes and subjected to repeated bouts of cyclical strains convert into myofibroblasts in the absence of any secondary soluble growth factors, demonstrating the fibroblast’s sensitivity to mechanical cues [81, 82]. In fact the rigidity of standard tissue culture plates can induce a fraction of otherwise quiescent fibroblasts to activate. Hence, multi-dimensional bioactive matrices (e.g. synthetic hydrogels or silicone substrates) and micro/nano-patterned surfaces provide improved in vitro methods for recapitulating a tissue’s physical environment. For instance, culturing fibroblasts, hepatic stellate cells, or mesenchymal cells in matrices of different elastic moduli demonstrate a positive correlation between tissue rigidity and myofibroblast differentiation. These in vitro data correspond to the finding that an injured tissue stiffens prior to signs of histopathologic fibrosis or matrix deposition, and likely precedes the emergence of fully differentiated myofibroblasts [83]. While a certain level of tissue stiffness must be achieved before αSMA incorporates into filamentous actin bundles, other quiescent fibroblast markers, like vimentin, are unresponsive to changes in the mechanical environment [10, 12, 84]. In comparison, culturing differentiated myofibroblast in compliant matrices that mimic healthy tissue causes partial reversion to a quiescent mesenchymal state [12, 13]. Fate-mapping studies in two different hepatic injury models revealed that myofibroblasts revert back to their original cell fate, but with a modified genetic signature permissive of accelerated conversion to a fibrotic myofibroblast upon additional injury [37]. These data suggest that myofibroblasts dedifferentiate to their original progenitor phenotype in response to trauma rather than regress by apoptotic mechanisms as previously proposed, suggesting they have genetic memory of their previous mechanical environment [37, 85].

Beyond direct manipulations of tissue mechanics, fibroblasts also respond to changes in matrix architecture, which has only recently been uncovered through nano-patterned scaffolds. Here matrices fabricated as an array of ridges that vary in depth, spacing, and directionality mimic the environmental topography created by the ECM. Scaffolds with densely packed grooves directed along a single axis, which is analogous to injury-induced ECM, increased focal adhesion maturity, cytoskeletal organization and migration speeds in fibroblasts [86-88]. Notably the ECM after infarct varies in terms of maturity but also isotropic organization [89], and these data suggest that the varied topography of the ECM impacts the maturation and density of differentiated myofibroblasts found in the injured myocardium.

Clearly, fibroblasts sense and interpret their mechanical surroundings. Uncovering how these signals integrate and transduce into their biologic outcome is an area of active research. The fibroblast’s physical interaction with the extracellular environment occurs via a contiguous structural complex comprised of the ECM, integrin-associated focal adhesions, and the actin cytoskeleton. These interactions convey multi-dimensional geometric information. Relative to chemical signaling, mechanical inputs can last for longer durations and extend over longer distances, often overriding chemical inputs that are also present [90]. In the context of myofibroblast differentiation, the actin cytoskeleton is a hub for integrating mechanical inputs into transcriptional events. Rho GTPases like Rho, Rac, and CDC42 reorganize the actin cytoskeleton into stress fibers that, in a myofibroblast, contain smooth muscle isoforms. They are activated by a number of profibrotic ligand-receptor complexes including TGFβR2, G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), Integrins, PDGFRα, and possibly TRP channels [91]. Rho factors, particularly RhoA, appear to govern αSMA stress fiber formation in fibroblasts and other mesenchymal cells, although targeted genetic approaches directed at RhoA, B, and C have not yet been used to support this hypothesis. A single study in human atrial fibroblasts found that the SMAD3-dependent myofibroblast transformation works through RhoB leaving undetermined which Rho-GTPase actually promotes a myofibroblast phenotype [92]. Downstream of Rho are 2 regulatory branches mediated by the Rho associated kinases (ROCK1 & 2) and the diaphanous family of formins (mDia), which are both required for polymerization and bundling stress fibers. RNAi-mediated knockdown of mDia in fibroblasts blocks tension-dependent αSMA transcription and myofibroblast differentiation [93]. Similarly, pharmacologic inhibition of ROCK blocks cytoskeletal remodeling and matrix gene expression in TGFβ stimulated fibroblasts [94-96]. Moreover, ischemic hearts from ROCK1 knockout mice fail to form myofibroblasts and have less fibrosis [97].

The Rho-GTPases and actin itself are directly linked to myofibroblast gene expression through SRF. SRF’s primary DNA target sequences are CArG boxes (CC(AT)6GG), which are found in many myofibroblast gene promoters including αSMA and Col1a [96, 98]. SRF-mediated myofibroblast gene transcription is sensitive to actin dynamics. Lantrunculin-B inhibits actin filament formation in response to profibrotic stimulants due to a loss of SRF transcriptional activity [95]. Both myocardial infarction and bleomycin lung injury in mice increase SRF expression. Accordingly, when mimicking this result in vitro, SRF overexpression has been shown to promote the differentiation of cardiac, lung, and esophageal fibroblasts into αSMA+ myofibroblasts [22, 43, 99, 100]. Conversely, SRF deletion from cardiac fibroblasts and MEFs blocks AngII and TGFβ-mediated myofibroblast conversion [43]. Beyond its actin-sensing mechanism SRF is a nodal convergence point for many of the signaling networks described above. In fact, the induction of Ca2+-Calcineurin-NFAT signaling by TGFβ requires SRF-mediated transcription of TRPC6 [22], yet surprisingly the ectopic expression of TRPC6 or a constitutively activate form of calcineurin in fibroblasts lacking SRF can still induce myofibroblast differentiation despite the loss of such a powerful transcription factor [22]. Notably, αSMA expression in smooth muscle cells requires a cooperative interaction between NFAT and SRF, which could be applicable to myofibroblast development. Recently, SRF was excised specifically in TCF21+ cardiac fibroblasts in vivo. At baseline the loss of SRF was innocuous [43]; however, myocardial infarction caused cardiac rupture in a substantial fraction of these mice, while those receiving a milder ischemic injury survived with nearly a 30% reduction in total myocardial fibrosis [43]. In a separate model, SRF was deleted in Postn+ dermal fibroblasts, which significantly delayed wound closure kinetics and elicited dermal rupture in some mice creating a larger wound [43].

SRF’s transcriptional activity is potently enhanced by the myocardin related transcription factor family (MRTF). MRTF-A (MAL or MKL1) and MRTF-B (MAL16 or MKL2) are widely expressed and directly regulated by actin cytoskeletal dynamics. MRTFs bind to G-actin monomers, which sequester them in the cytosol, but as F-actin bundles into stress fibers, the G-actin monomer pool depletes, thereby freeing MRTFs to translocate to the nucleus. Once in the nucleus MRTF-A and B bind SRF, which potentiates SRF target gene transcription. Overexpression of MRTF-A converts cardiac fibroblasts into αSMA+ myofibroblasts [96]. Similarly mechanical induction of myofibroblast transformation correlates with the nuclear accumulation of MRTF-A [101]. Conversely, myofibroblast differentiation is significantly blocked by knocking down MRTF-A or pharmacologically inhibiting actin regulators like the Rho-GTPases [96, 102]. In line with these data the global loss of MRTF-A in mice antagonizes fibrotic scarring after myocardial infarction and chronic neurohumoral stimulation [96]. Tissue collected from the border zone of infarcted MRTF-A null mice have reduced ECM (Col1a, Col3a, and Elastin) and contractile gene expression (αSMA and SM-22) [96]. The sensitivity of this pathway to actin dynamics suggests that Rho/MRTF-SRF signaling predominate during late myofibroblast differentiation, perhaps to reach full maturation when compared to TGFβ signaling which appears more critical to induction. This hypothesis could explain why MRTF-A null mice are not susceptible to cardiac rupture after myocardial infarction MI [96, 103]. Because TGFβ and Rho signaling rely on SRF mediated myofibroblast gene transcription, these pathways likely run in parallel to reinforce each others signals.

Additional signaling pathways that transduce mechanical stimuli into myofibroblast differentiation are continuing to emerge. For instance, the transcriptional coactivators of the HIPPO pathway yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional coactivator with a PDZ domain (TAZ) translocate to the nucleus in response to mechanical stimuli [85]. In lung fibroblasts from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis there is enhanced nuclear localization of both factors [104]. Conversely, knockdown of YAP or TAZ in skin, liver, and kidney fibroblasts decreases TGFβ and αSMA expression [105-107]. Similarly, TAZ deficient mice have a blunted fibrotic response to bleomycin-induced lung injury [108], while pharmacologic inhibition of YAP impairs liver stromal cells from activating and becoming fibrotic in response to toxic stimuli [106]. The role of YAP and TAZ has not been examined specifically in cardiac fibroblasts, but loss of YAP/TAZ function in myocytes promotes fibrosis [109, 110].

Other mechanically sensitive factors include several MAPK family members like ERK, JNK, and p38 that were reviewed earlier. Passively stretching rodent cardiac fibroblasts activates ERK and JNK; whereas, p38 is activated by perpendicular tractions forces that are transmitted through the integrin-actin cytoskeletal complex [67]. These forces send p38 to the nucleus where it synergizes with transcription factors to promote actin expression. Conversely, p38 inhibitors block the tension-dependent actin remodeling that is characteristic of myofibroblast transformation. In non-fibroblast cell types, p38 regulates actin polymerization and stress fiber formation, suggesting a global role for p38 in transducing mechanical signals into cytoskeletal changes [111-114]. Taken together, p38 and SRF appear to be the primary integrators of signals from several growth factors and mechanically-activated pathways that drive myofibroblast differentiation (Figure 2). The PI3K/AKT pathway is also mechanically responsive in VICs, which like fibroblasts, convert into myofibroblasts when cultured in stiff matrices [13]. This response is antagonized by preventing PI3K/AKT signaling. In lung tissue, focal-adhesion mediated myofibroblast differentiation also depends on AKT signaling, supporting the role of PI3K/AKT in fibroblast mechanotransduction [115].

3.4 Transcriptome Regulation by RNA Binding Proteins

RNA binding proteins (RBPs) have emerged as potent downstream components of signaling networks that regulate disease and differentiation. RBPs regulate all facets of RNA maturation including alternative splicing, stability, polyadenylation, and transcript localization [116-118]. This function coupled with having pleitropic RNA targets make RBPs powerful differentiation factors as they can completely alter a cell’s phenotype just through modulating their activity or expression. Until recently mechanisms involving RNA maturation have not been associated with fibrosis or the myofibroblast. However, genome wide screening for regulators of myofibroblast differentiation uncovered the RBP, muscleblind-like 1 (MBNL1)[43]. MBNL1 is part of a conserved family of proteins encoded by 3 different genes that use zinc finger domains to interact with CUG repeat regions of RNAs [119, 120]. When MBNL1 proteins are functionally sequestered from their normal RNA targets inappropriate maturation of gene products ensue resulting in myotonic dystrophy [121, 122], blocking cardiac myocyte maturation [123], or inhibition of embryonic stem cell differentiation [124].

In the cardiac fibroblast MBNL1 is normally expressed at extremely low levels, but with myocardial infarction or profibrotic agonists MBNL1 expression markedly increases [43]. Overexpression of MBNL1 in a variety of fibroblasts promotes myofibroblast differentiation as defined by αSMA+ stress fibers, contractility, and ECM gene transcription; whereas, MBNL1 null fibroblasts fail to differentiate in response to TGFβ treatment [43]. Moreover, MBNL1 knockout mice have impaired dermal wound healing and poor survivability in response to myocardial infarction [43]. Post-mortem examination revealed that MBNL1 null mice had a markedly diminished fibrotic response and significantly fewer myofibroblasts when compared to their injured wild-type littermates. To directly examine whether MBNL1 underlies myofibroblast differentiation in vivo, an MBNL1 transgene was conditionally overexpressed in TCF21+ cardiac fibroblasts, which caused mild fibrosis to develop in otherwise healthy hearts [43]. With chronic AngII infusion the fibrotic area nearly doubled when compared to non-transgenic controls demonstrating that MBNL1 is a bona fide promoter of myofibroblast differentiation. Notably, TCF21+ interstitial cells are also in the kidney and lung, and like the heart these organs turned fibrotic with MBNL1 overexpression. MBNL1-regulated transcripts were identified by RNA-immunoprecipitation (RIP) and RNAseq. Here MBNL1 interacted with ~2500 transcripts that clustered into functional pathways associated with chemokine signaling, TGFβ signaling, MAPK signaling, actin cytoskeletons, focal adhesion, adheren junctions and cell cycle regulation [43]. Molecular constituents of several of these pathways were already known as fundamental regulators of myofibroblast differentiation [39]. MBNL1 promoted myofibroblast differentiation in part by stabilizing several of those known transcripts including TGFβR2, SRF, and calcineurin. Interestingly, MBNL1 stabilized all of the spliced variants of calcineurin, one of which is constitutively active. As discussed above activated calcineurin is sufficient for converting fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, which was reconfirmed in this study [43]. Given the important role SRF plays in myofibroblast differentiation the regulation of SRF mRNA by MBNL1 was also examined in greater depth. TGFβ and MBNL1-mediated myofibroblast differentiation was occurring through a distal MBNL1 binding site in SRF’s 3’ UTR that stabilizes the SRF transcript [43]. These results defined an entirely new regulatory mechanism involving the maturation of select transcripts that serve as integral effectors within the key signaling networks orchestrating myofibroblast differentiation. MBNL1’s regulation of the fibroblast transcriptome represents a rapid mechanism for simultaneously activating several nodal signaling axes that transition fibroblasts into the myofibroblast cell fate.

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

Fibrosis is the pathologic consequence of a chronically active wound healing response that is a universal signature of disease in most organs. Despite this tissue diversity, myofibroblast function is a unified determinant of fibrosis regardless of the inciting stimulus for disease. Our understanding of the cellular and molecular underpinnings of cardiac fibrosis is still in its infancy with many important questions regarding the basic tenets of fibroblast and myofibroblast biology left unknown. While it’s now clear that the genetic signature or lineage of a fibroblast varies within tissues including the heart, how this heterogeneity effects their function and potential to differentiate into myofibroblasts has yet to be studied leaving open the question of whether all fibroblast populations contribute to the fibrotic response. Myofibroblast differentiation also invokes a powerful feed forward loop that reinforces the fibrotic response through recurring bouts of tissue stiffening and matrix deposition. Whether this recurrent stiffening of the heart causes fibroblasts to terminally differentiate particularly in an environment like the myocardium where the functional tissue fails to renew is still unknown, but underscores the importance of temporally defining in vivo the stages of myofibroblast differentiation in response to different cardiac pathologies. Along this same line the heart’s fibrotic response varies by injury in which pathologies like hypertension, diabetes, and aging cause reactive interstitial fibrosis versus ischemia and myocardial infarction, which cause replacement fibrosis and scarring. The basis for this differential fibrotic response has not been rigorously studied, but is important to understand for translating basic research into clinically viable therapies for fibrosis. As for now manipulating the existence of myofibroblasts through promoting or eliminating regulators of its cell fate in vivo demonstrates that targeting this cell effectively modulates wound closure kinetics and the fibrotic response providing strong rational for studying myofibroblast biology and identifying therapies directed at halting myofibroblast formation or regressing myofibroblasts back into its precursor once the initial injury response has subsided. Here we detailed 4 key branches of the myofibroblast differentiation network, and at any of these points pharmacologic inhibition would be expected to entirely short circuit external cues to differentiate and secrete fibrotic matrix. Several of the molecular regulators discussed here are already pharmacologically tractable and include p38, MRTF, ROCK1/2, Calcineurin, and TRPC6. Despite these prospective targets cellular specificity as well as myocyte renewal remain confounding variables when considering targeting these pathways for clinically managing fibrosis in patients with cardiovascular disease or heart failure.

Highlights.

Myofibroblasts are primarily derived from resident fibroblasts.

MAPK signaling regulates fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation.

Ca2+ signals from the TRP channel family initiates myofibroblast differentiation.

The cytoskeleton senses the environment and imparts signals to differentiate.

RNA binding proteins mature the transcriptome to promote differentiation.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported with funds from the National Institute of Health (R00HL119353-01 & HL108806-04).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

None.

References

- [1].Bruder O, Wagner A, Jensen CJ, Schneider S, Ong P, Kispert EM, et al. Myocardial scar visualized by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging predicts major adverse events in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010;56:875–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Elliott PM, Poloniecki J, Dickie S, Sharma S, Monserrat L, Varnava A, et al. Sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: identification of high risk patients. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000;36:2212–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Spirito P, Casey SA, Bellone P, Gohman TE, et al. Epidemiology of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-related death: revisited in a large non-referral-based patient population. Circulation. 2000;102:858–64. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.8.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].O'Hanlon R, Grasso A, Roughton M, Moon JC, Clark S, Wage R, et al. Prognostic significance of myocardial fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010;56:867–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Galli A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast: one function, multiple origins. Am. J. Pathol. 2007;170:1807–16. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:349–63. doi: 10.1038/nrm809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast in wound healing and fibrocontractive diseases. J. Pathol. 2003;200:500–3. doi: 10.1002/path.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sun Y, Weber KT. Infarct scar: a dynamic tissue. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000;46:250–6. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hinz B. Tissue stiffness, latent TGF-beta1 activation, and mechanical signal transduction: implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of fibrosis. Current rheumatology reports. 2009;11:120–6. doi: 10.1007/s11926-009-0017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hinz B. The myofibroblast: paradigm for a mechanically active cell. J. Biomech. 2010;43:146–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Muthusubramaniam L, Zaitseva T, Paukshto M, Martin G, Desai T. Effect of collagen nanotopography on keloid fibroblast proliferation and matrix synthesis: implications for dermal wound healing. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2014;20:2728–36. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wang H, Haeger SM, Kloxin AM, Leinwand LA, Anseth KS. Redirecting valvular myofibroblasts into dormant fibroblasts through light-mediated reduction in substrate modulus. PloS one. 2012;7:e39969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wang H, Tibbitt MW, Langer SJ, Leinwand LA, Anseth KS. Hydrogels preserve native phenotypes of valvular fibroblasts through an elasticity-regulated PI3K/AKT pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110:19336–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306369110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Suzuki J, Isobe M, Aikawa M, Kawauchi M, Shiojima I, Kobayashi N, et al. Nonmuscle and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain expression in rejected cardiac allografts. A study in rat and monkey models. Circulation. 1996;94:1118–24. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.5.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rice NA, Leinwand LA. Skeletal myosin heavy chain function in cultured lung myofibroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 2003;163:119–29. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Serini G, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Ropraz P, Geinoz A, Borsi L, Zardi L, et al. The fibronectin domain ED-A is crucial for myofibroblastic phenotype induction by transforming growth factor-beta1. J. Cell Biol. 1998;142:873–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.3.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].White ES, Muro AF. Fibronectin splice variants: understanding their multiple roles in health and disease using engineered mouse models. IUBMB Life. 2011;63:538–46. doi: 10.1002/iub.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hinz B. Masters and servants of the force: the role of matrix adhesions in myofibroblast force perception and transmission. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2006;85:175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Arslan F, Smeets MB, Riem Vis PW, Karper JC, Quax PH, Bongartz LG, et al. Lack of fibronectin-EDA promotes survival and prevents adverse remodeling and heart function deterioration after myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 2011;108:582–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.224428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hinz B. Formation and function of the myofibroblast during tissue repair. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2007;127:526–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hinz B, Pittet P, Smith-Clerc J, Chaponnier C, Meister JJ. Myofibroblast development is characterized by specific cell-cell adherens junctions. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:4310–20. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-05-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Davis J, Burr AR, Davis GF, Birnbaumer L, Molkentin JD. A TRPC6-dependent pathway for myofibroblast transdifferentiation and wound healing in vivo. Dev. Cell. 2012;23:705–15. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Acharya A, Baek ST, Huang G, Eskiocak B, Goetsch S, Sung CY, et al. The bHLH transcription factor Tcf21 is required for lineage-specific EMT of cardiac fibroblast progenitors. Development. 2012;139:2139–49. doi: 10.1242/dev.079970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Moore-Morris T, Guimaraes-Camboa N, Banerjee I, Zambon AC, Kisseleva T, Velayoudon A, et al. Resident fibroblast lineages mediate pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:2921–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI74783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Furtado MB, Costa MW, Pranoto EA, Salimova E, Pinto AR, Lam NT, et al. Cardiogenic genes expressed in cardiac fibroblasts contribute to heart development and repair. Circ. Res. 2014;114:1422–34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ali SR, Ranjbarvaziri S, Talkhabi M, Zhao P, Subat A, Hojjat A, et al. Developmental heterogeneity of cardiac fibroblasts does not predict pathological proliferation and activation. Circ. Res. 2014;115:625–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Pinto AR, Ilinykh A, Ivey MJ, Kuwabara JT, D'Antoni M, Debuque RJ, et al. Revisiting Cardiac Cellular Composition. Circ. Res. 2015 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Crawford JR, Haudek SB, Cieslik KA, Trial J, Entman ML. Origin of developmental precursors dictates the pathophysiologic role of cardiac fibroblasts. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2012;5:749–59. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9402-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Haudek SB, Cheng J, Du J, Wang Y, Hermosillo-Rodriguez J, Trial J, et al. Monocytic fibroblast precursors mediate fibrosis in angiotensin-II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Haudek SB, Trial J, Xia Y, Gupta D, Pilling D, Entman ML. Fc receptor engagement mediates differentiation of cardiac fibroblast precursor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:10179–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804910105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Haudek SB, Xia Y, Huebener P, Lee JM, Carlson S, Crawford JR, et al. Bone marrow-derived fibroblast precursors mediate ischemic cardiomyopathy in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:18284–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608799103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Moeller A, Gilpin SE, Ask K, Cox G, Cook D, Gauldie J, et al. Circulating fibrocytes are an indicator of poor prognosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit.Care Med. 2009;179:588–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1534OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:1420–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zeisberg EM, Kalluri R. Origins of cardiac fibroblasts. Circ. Res. 2010;107:1304–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zeisberg EM, Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M, Dorfman AL, McMullen JR, Gustafsson E, et al. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat. Med. 2007;13:952–61. doi: 10.1038/nm1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhou B, Honor LB, He H, Ma Q, Oh JH, Butterfield C, et al. Adult mouse epicardium modulates myocardial injury by secreting paracrine factors. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:1894–904. doi: 10.1172/JCI45529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kisseleva T, Cong M, Paik Y, Scholten D, Jiang C, Benner C, et al. Myofibroblasts revert to an inactive phenotype during regression of liver fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2012;109:9448–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201840109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Snider P, Standley KN, Wang J, Azhar M, Doetschman T, Conway SJ. Origin of cardiac fibroblasts and the role of periostin. Circ. Res. 2009;105:934–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.201400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Davis J, Molkentin JD. Myofibroblasts: trust your heart and let fate decide. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014;70:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Takeda N, Manabe I, Uchino Y, Eguchi K, Matsumoto S, Nishimura S, et al. Cardiac fibroblasts are essential for the adaptive response of the murine heart to pressure overload. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:254–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI40295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Oka T, Xu J, Kaiser RA, Melendez J, Hambleton M, Sargent MA, et al. Genetic manipulation of periostin expression reveals a role in cardiac hypertrophy and ventricular remodeling. Circ. Res. 2007;101:313–21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.149047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Shimazaki M, Nakamura K, Kii I, Kashima T, Amizuka N, Li M, et al. Periostin is essential for cardiac healing after acute myocardial infarction. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:295–303. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Davis J, Salomonis N, Ghearing N, Lin SC, Kwong JQ, Mohan A, et al. MBNL1-mediated regulation of differentiation RNAs promotes myofibroblast transformation and the fibrotic response. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:10084. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Qian L, Huang Y, Spencer CI, Foley A, Vedantham V, Liu L, et al. In vivo reprogramming of murine cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2012;485:593–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].VanDusen NJ, Vincentz JW, Firulli BA, Howard MJ, Rubart M, Firulli AB. Loss of Hand2 in a population of Periostin lineage cells results in pronounced bradycardia and neonatal death. Dev. Biol. 2014;388:149–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chu PY, Mariani J, Finch S, McMullen JR, Sadoshima J, Marshall T, et al. Bone marrow-derived cells contribute to fibrosis in the chronically failing heart. Am. J. Pathol. 2010;176:1735–42. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ieronimakis N, Hays AL, Janebodin K, Mahoney WM, Jr., Duffield JS, Majesky MW, et al. Coronary adventitial cells are linked to perivascular cardiac fibrosis via TGFbeta1 signaling in the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2013;63:122–34. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kramann R, Schneider RK, DiRocco DP, Machado F, Fleig S, Bondzie PA, et al. Perivascular Gli1+ progenitors are key contributors to injury-induced organ fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:51–66. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Chang HY, Chi JT, Dudoit S, Bondre C, van de Rijn M, Botstein D, et al. Diversity, topographic differentiation, and positional memory in human fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99:12877–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162488599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Wipff PJ, Rifkin DB, Meister JJ, Hinz B. Myofibroblast contraction activates latent TGF-beta1 from the extracellular matrix. J. Cell. Biol. 2007;179:1311–23. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Leask A, Abraham DJ. TGF-beta signaling and the fibrotic response. Faseb J. 2004;18:816–27. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1273rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Hecker L, Vittal R, Jones T, Jagirdar R, Luckhardt TR, Horowitz JC, et al. NADPH oxidase-4 mediates myofibroblast activation and fibrogenic responses to lung injury. Nat. Med. 2009;15:1077–81. doi: 10.1038/nm.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Bonniaud P, Kolb M, Galt T, Robertson J, Robbins C, Stampfli M, et al. Smad3 null mice develop airspace enlargement and are resistant to TGF-beta-mediated pulmonary fibrosis. J. Immunol. 2004;173:2099–108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Dobaczewski M, Bujak M, Li N, Gonzalez-Quesada C, Mendoza LH, Wang XF, et al. Smad3 signaling critically regulates fibroblast phenotype and function in healing myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 2010;107:418–28. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.216101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Lal H, Ahmad F, Zhou J, Yu JE, Vagnozzi RJ, Guo Y, et al. Cardiac fibroblast glycogen synthase kinase-3beta regulates ventricular remodeling and dysfunction in ischemic heart. Circulation. 2014;130:419–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Koitabashi N, Danner T, Zaiman AL, Pinto YM, Rowell J, Mankowski J, et al. Pivotal role of cardiomyocyte TGF-beta signaling in the murine pathological response to sustained pressure overload. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:2301–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI44824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Watkins SJ, Jonker L, Arthur HM. A direct interaction between TGFbeta activated kinase 1 and the TGFbeta type II receptor: implications for TGFbeta signalling and cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006;69:432–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Yu L, Hebert MC, Zhang YE. TGF-beta receptor-activated p38 MAP kinase mediates Smad-independent TGF-beta responses. The EMBO journal. 2002;21:3749–59. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zhang YE. Non-Smad pathways in TGF-beta signaling. Cell Res. 2009;19:128–39. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Akhurst RJ, Hata A. Targeting the TGFbeta signalling pathway in disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012;11:790–811. doi: 10.1038/nrd3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Bakin AV, Rinehart C, Tomlinson AK, Arteaga CL. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for TGFbeta-mediated fibroblastic transdifferentiation and cell migration. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:3193–206. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.15.3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Meyer-Ter-Vehn T, Gebhardt S, Sebald W, Buttmann M, Grehn F, Schlunck G, et al. p38 inhibitors prevent TGF-beta-induced myofibroblast transdifferentiation in human tenon fibroblasts. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47:1500–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Meyer-Ter-Vehn T, Katzenberger B, Han H, Grehn F, Schlunck G. Lovastatin inhibits TGF-beta-induced myofibroblast transdifferentiation in human tenon fibroblasts. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008;49:3955–60. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Sato M, Shegogue D, Gore EA, Smith EA, McDermott PJ, Trojanowska M. Role of p38 MAPK in transforming growth factor beta stimulation of collagen production by scleroderma and healthy dermal fibroblasts. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2002;118:704–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Stambe C, Atkins RC, Tesch GH, Masaki T, Schreiner GF, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. The role of p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in renal fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004;15:370–9. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000109669.23650.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Vepachedu R, Gorska MM, Singhania N, Cosgrove GP, Brown KK, Alam R. Unc119 regulates myofibroblast differentiation through the activation of Fyn and the p38 MAPK pathway. J. Immunol. 2007;179:682–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Wang J, Chen H, Seth A, McCulloch CA. Mechanical force regulation of myofibroblast differentiation in cardiac fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003;285:H1871–81. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00387.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Wang J, Fan J, Laschinger C, Arora PD, Kapus A, Seth A, et al. Smooth muscle actin determines mechanical force-induced p38 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:7273–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Liu Q, Busby JC, Molkentin JD. Interaction between TAK1-TAB1-TAB2 and RCAN1-calcineurin defines a signalling nodal control point. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:154–61. doi: 10.1038/ncb1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Zhang D, Gaussin V, Taffet GE, Belaguli NS, Yamada M, Schwartz RJ, et al. TAK1 is activated in the myocardium after pressure overload and is sufficient to provoke heart failure in transgenic mice. Nat. Med. 2000;6:556–63. doi: 10.1038/75037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Kim SI, Kwak JH, Zachariah M, He Y, Wang L, Choi ME. TGF-beta-activated kinase 1 and TAK1-binding protein 1 cooperate to mediate TGF-beta1-induced MKK3-p38 MAPK activation and stimulation of type I collagen. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F1471–8. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00485.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Wang L, Ma R, Flavell RA, Choi ME. Requirement of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3 (MKK3) for activation of p38alpha and p38delta MAPK isoforms by TGF-beta 1 in murine mesangial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:47257–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Kompa AR, See F, Lewis DA, Adrahtas A, Cantwell DM, Wang BH, et al. Long-term but not short-term p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition improves cardiac function and reduces cardiac remodeling post-myocardial infarction. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 2008;325:741–50. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.133546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].See F, Thomas W, Way K, Tzanidis A, Kompa A, Lewis D, et al. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition improves cardiac function and attenuates left ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction in the rat. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004;44:1679–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Liu T, Warburton RR, Guevara OE, Hill NS, Fanburg BL, Gaestel M, et al. Lack of MK2 inhibits myofibroblast formation and exacerbates pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2007;37:507–17. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0077OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Sousa AM, Liu T, Guevara O, Stevens J, Fanburg BL, Gaestel M, et al. Smooth muscle alpha-actin expression and myofibroblast differentiation by TGFbeta are dependent upon MK2. J. Cell. Biochem. 2007;100:1581–92. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Du J, Xie J, Zhang Z, Tsujikawa H, Fusco D, Silverman D, et al. TRPM7-mediated Ca2+ signals confer fibrogenesis in human atrial fibrillation. Circ. Res. 2010;106:992–1003. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Adapala RK, Thoppil RJ, Luther DJ, Paruchuri S, Meszaros JG, Chilian WM, et al. TRPV4 channels mediate cardiac fibroblast differentiation by integrating mechanical and soluble signals. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2013;54:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Rahaman SO, Grove LM, Paruchuri S, Southern BD, Abraham S, Niese KA, et al. TRPV4 mediates myofibroblast differentiation and pulmonary fibrosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:5225–38. doi: 10.1172/JCI75331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Ambudkar IS, Bandyopadhyay BC, Liu X, Lockwich TP, Paria B, Ong HL. Functional organization of TRPC-Ca2+ channels and regulation of calcium microdomains. Cell Calcium. 2006;40:495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Wang JH, Thampatty BP, Lin JS, Im HJ. Mechanoregulation of gene expression in fibroblasts. Gene. 2007;391:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Kessler D, Dethlefsen S, Haase I, Plomann M, Hirche F, Krieg T, et al. Fibroblasts in mechanically stressed collagen lattices assume a "synthetic" phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:36575–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101602200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Georges PC, Hui JJ, Gombos Z, McCormick ME, Wang AY, Uemura M, et al. Increased stiffness of the rat liver precedes matrix deposition: implications for fibrosis. Am. J. Phys.Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G1147–54. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00032.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Sandbo N, Dulin N. Actin cytoskeleton in myofibroblast differentiation: ultrastructure defining form and driving function. Transl. Res. 2011;158:181–96. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Yang C, Tibbitt MW, Basta L, Anseth KS. Mechanical memory and dosing influence stem cell fate. Nature Materials. 2014;13:645–52. doi: 10.1038/nmat3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Biela SA, Su Y, Spatz JP, Kemkemer R. Different sensitivity of human endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts to topography in the nano-micro range. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:2460–6. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Kim DH, Han K, Gupta K, Kwon KW, Suh KY, Levchenko A. Mechanosensitivity of fibroblast cell shape and movement to anisotropic substratum topography gradients. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5433–44. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Chaterji S, Kim P, Choe SH, Tsui JH, Lam CH, Ho DS, et al. Synergistic effects of matrix nanotopography and stiffness on vascular smooth muscle cell function. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2014;20:2115–26. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Clarke SA, Richardson WJ, Holmes JW. Modifying the mechanics of healing infarcts: Is better the enemy of good? J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Janmey PA, Wells RG, Assoian RK, McCulloch CA. From tissue mechanics to transcription factors. Differentiation. 2013;86:112–20. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Olson EN, Nordheim A. Linking actin dynamics and gene transcription to drive cellular motile functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:353–65. doi: 10.1038/nrm2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Porter KE, Turner NA, O'Regan DJ, Balmforth AJ, Ball SG. Simvastatin reduces human atrial myofibroblast proliferation independently of cholesterol lowering via inhibition of RhoA. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004;61:745–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Chan MW, Chaudary F, Lee W, Copeland JW, McCulloch CA. Force-induced myofibroblast differentiation through collagen receptors is dependent on mammalian diaphanous (mDia) J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:9273–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.075218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Akhmetshina A, Dees C, Pileckyte M, Szucs G, Spriewald BM, Zwerina J, et al. Rho-associated kinases are crucial for myofibroblast differentiation and production of extracellular matrix in scleroderma fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2553–64. doi: 10.1002/art.23677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Sandbo N, Kregel S, Taurin S, Bhorade S, Dulin NO. Critical role of serum response factor in pulmonary myofibroblast differentiation induced by TGF-beta. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2009;41:332–8. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0288OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Small EM, Thatcher JE, Sutherland LB, Kinoshita H, Gerard RD, Richardson JA, et al. Myocardin-related transcription factor-a controls myofibroblast activation and fibrosis in response to myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 2010;107:294–304. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Haudek SB, Gupta D, Dewald O, Schwartz RJ, Wei L, Trial J, et al. Rho kinase-1 mediates cardiac fibrosis by regulating fibroblast precursor cell differentiation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009;83:511–8. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Luchsinger LL, Patenaude CA, Smith BD, Layne MD. Myocardin-related transcription factor-A complexes activate type I collagen expression in lung fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:44116–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.276931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Chai J, Norng M, Tarnawski AS, Chow J. A critical role of serum response factor in myofibroblast differentiation during experimental oesophageal ulcer healing in rats. Gut. 2007;56:621–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.106674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Yang Y, Zhe X, Phan SH, Ullenbruch M, Schuger L. Involvement of serum response factor isoforms in myofibroblast differentiation during bleomycin-induced lung injury. Am J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2003;29:583–90. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0315OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Shiwen X, Stratton R, Nikitorowicz-Buniak J, Ahmed-Abdi B, Ponticos M, Denton C, et al. A Role of Myocardin Related Transcription Factor-A (MRTF-A) in Scleroderma Related Fibrosis. PloS one. 2015;10:e0126015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Huang X, Yang N, Fiore VF, Barker TH, Sun Y, Morris SW, et al. Matrix stiffness-induced myofibroblast differentiation is mediated by intrinsic mechanotransduction. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012;47:340–8. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0050OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Small EM. The actin-MRTF-SRF gene regulatory axis and myofibroblast differentiation. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2012;5:794–804. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Wada K, Itoga K, Okano T, Yonemura S, Sasaki H. Hippo pathway regulation by cell morphology and stress fibers. Development. 2011;138:3907–14. doi: 10.1242/dev.070987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Liu F, Lagares D, Choi KM, Stopfer L, Marinkovic A, Vrbanac V, et al. Mechanosignaling through YAP and TAZ drives fibroblast activation and fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2015;308:L344–57. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00300.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Mannaerts I, Leite SB, Verhulst S, Claerhout S, Eysackers N, Thoen LF, et al. The Hippo pathway effector YAP controls mouse hepatic stellate cell activation. J. Hepatol. 2015;63:679–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Piersma B, de Rond S, Werker PM, Boo S, Hinz B, van Beuge MM, et al. YAP1 Is a Driver of Myofibroblast Differentiation in Normal and Diseased Fibroblasts. Am. J. Pathol. 2015;185:3326–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Mitani A, Nagase T, Fukuchi K, Aburatani H, Makita R, Kurihara H. Transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif is essential for normal alveolarization in mice. Am. J. Respir. Crit.Care Med. 2009;180:326–38. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200812-1827OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Lin Z, von Gise A, Zhou P, Gu F, Ma Q, Jiang J, et al. Cardiac-specific YAP activation improves cardiac function and survival in an experimental murine MI model. Circ. Res. 2014;115:354–63. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Xin M, Kim Y, Sutherland LB, Murakami M, Qi X, McAnally J, et al. Hippo pathway effector Yap promotes cardiac regeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110:13839–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313192110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Garcia JG, Wang P, Schaphorst KL, Becker PM, Borbiev T, Liu F, et al. Critical involvement of p38 MAP kinase in pertussis toxin-induced cytoskeletal reorganization and lung permeability. Faseb. J. 2002;16:1064–76. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0895com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Wang J, Zohar R, McCulloch CA. Multiple roles of alpha-smooth muscle actin in mechanotransduction. Experimental cell research. 2006;312:205–14. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Cui X, Zhang X, Yin Q, Meng A, Su S, Jing X, et al. Factin cytoskeleton reorganization is associated with hepatic stellate cell activation. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014;9:1641–7. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Yu L, Yuan X, Wang D, Barakat B, Williams ED, Hannigan GE. Selective regulation of p38beta protein and signaling by integrin-linked kinase mediates bladder cancer cell migration. Oncogene. 2014;33:690–701. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Kulkarni AA, Thatcher TH, Olsen KC, Maggirwar SB, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. PPAR-gamma ligands repress TGFbeta-induced myofibroblast differentiation by targeting the PI3K/Akt pathway: implications for therapy of fibrosis. PloS one. 2011;6:e15909. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Wang ET, Cody NA, Jog S, Biancolella M, Wang TT, Treacy DJ, et al. Transcriptome-wide regulation of pre-mRNA splicing and mRNA localization by muscleblind proteins. Cell. 2012;150:710–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Besse F, Ephrussi A. Translational control of localized mRNAs: restricting protein synthesis in space and time. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:971–80. doi: 10.1038/nrm2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Batra R, Charizanis K, Manchanda M, Mohan A, Li M, Finn DJ, et al. Loss of MBNL leads to disruption of developmentally regulated alternative polyadenylation in RNA-mediated disease. Mol. Cell. 2014;56:311–22. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Ho TH, Charlet BN, Poulos MG, Singh G, Swanson MS, Cooper TA. Muscleblind proteins regulate alternative splicing. EMBO J. 2004;23:3103–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Teplova M, Patel DJ. Structural insights into RNA recognition by the alternative-splicing regulator muscleblind-like MBNL1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:1343–51. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Lin X, Miller JW, Mankodi A, Kanadia RN, Yuan Y, Moxley RT, et al. Failure of MBNL1-dependent post-natal splicing transitions in myotonic dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:2087–97. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Miller JW, Urbinati CR, Teng-Umnuay P, Stenberg MG, Byrne BJ, Thornton CA, et al. Recruitment of human muscleblind proteins to (CUG)(n) expansions associated with myotonic dystrophy. EMBO J. 2000;19:4439–48. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Kalsotra A, Xiao X, Ward AJ, Castle JC, Johnson JM, Burge CB, et al. A postnatal switch of CELF and MBNL proteins reprograms alternative splicing in the developing heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:20333–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809045105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Han H, Irimia M, Ross PJ, Sung HK, Alipanahi B, David L, et al. MBNL proteins repress ES-cell-specific alternative splicing and reprogramming. Nature. 2013;498:241–5. doi: 10.1038/nature12270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]