Abstract

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the most lethal gynaecological malignancy worldwide. Development of chemoresistance and peritoneal dissemination of EOC cells are the major reasons for low survival rate. Targeting signal transduction pathways which promote therapy resistance and metastatic dissemination is the key to successful treatment. Members of the ErbB family of receptors are over-expressed in EOC and play key roles in chemoresistance and invasiveness. Despite this, single-targeted ErbB inhibitors have demonstrated limited activity in chemoresistant EOC. In this report, we show that dacomitinib, a pan-ErbB receptor inhibitor, diminished growth, clonogenic potential, anoikis resistance and induced apoptotic cell death in therapy-resistant EOC cells. Dacominitib inhibited PLK1-FOXM1 signalling pathway and its down-stream targets Aurora kinase B and survivin. Moreover, dacomitinib attenuated migration and invasion of the EOC cells and reduced expression of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers ZEB1, ZEB2 and CDH2 (which encodes N-cadherin). Conversely, the anti-tumour activity of single-targeted ErbB agents including cetuximab (a ligand-blocking anti-EGFR mAb), transtuzumab (anti-HER2 mAb), H3.105.5 (anti-HER3 mAb) and erlotinib (EGFR small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor) were marginal. Our results provide a rationale for further investigation on the therapeutic potential of dacomitinib in treatment of the chemoresistant EOC.

Introduction

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death among women worldwide and accounts for the highest mortality rate of all gynaecological malignancies. Each year, over 22000 women are diagnosed with EOC in the United States an estimated 14000 patients die from this disease1. Late-stage diagnosis, peritoneal metastasis and development of chemoresistance restrain improvements in overall survival rate. Despite debulking surgery and aggressive platinum/taxane-based chemotherapy regimens, the majority of patients relapse after achieving a complete clinical response2, 3. Inherent and acquired resistance to chemotherapeutics are responsible for treatment failure in EOC4. Patients with the recurrent disease are treated with gemcitabine and bevacizumab (anti-VEGFA mAb) but clinical trials report that the median overall survival is still dismal5, 6. Therefore, there is a pressing need to establish more effective therapies against chemoresistant EOC.

The ErbB or epidermal growth factor (EGF) family of receptor tyrosine kinases consists of four closely related members including EGFR, HER2, HER3 and HER47. This family plays key roles in tumour growth, metastasis and therapy resistance through activation of down-stream pathways such as Ras/MAPK and PI3K/AKT8, 9. Evidence indicates that the ErbB family members are overexpressed in EOC which correlates with poor survival10. EGFR is overexpressed in 30–98% of EOC in all histologic subtypes11, 12. Enhanced expression of EGFR and its ligands correlate with advanced-stage disease, lack of therapeutic response and decreased recurrence-free survival13–15. HER2 gene amplification and over-expression are found in different subtypes of EOC and associate with a higher recurrence frequency16, 17. Moreover, HER3 is up-regulated in EOC clinical samples which correlates with a worse prognosis18, 19.

The ErbB family is thought to drive malignant progression in EOC20, 21. EGFR and HER2 promote growth and chemoresistance22, 23. Moreover, HER3 and its ligand heregulin (HRG) play a central role in hematogenous dissemination of EOC cells to the omentum. HER3 is highly expressed in omental metastases in EOC patients and its knockdown impairs this organotropism in vivo 24. Altogether, these studies highlight the importance of the ErbB network in promoting growth, chemoresistance and metastatic progression in EOC and suggest that therapeutically disabling this family may hinder growth, survival and motility of EOC cells.

Despite the importance of EGFR in malignant progression in EOC, clinical trials with single-targeted agents such as cetuximab (anti-EGFR mAb), gefitinib and erlotinib (EGFR small molecule inhibitors) have demonstrated limited activity25–27. Trials of EGFR-directed therapies in combination with chemotherapeutics or other targeted therapies such as bevacizumab have also shown limited clinical benefit28–30. Furthermore, HER2-targeted therapies including trastuzumab and pertuzumab have proven to be of no benefit in EOC patients31, 32. Refinement of the ErbB-targeted therapeutics is therefore warranted to address resistance and maximize potential benefit in EOC patients.

Dacomitinib (Pfizer) is an irreversible second-generation pan-ErbB inhibitor33. A phase I study in patients with advanced solid tumours has demonstrated well-tolerated doses with significant antitumor activity34. Dacomitinib has shown promising clinical activity in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients who progressed on platinum therapy and were previously treated with erlotinib35, 36. In vitro studies have reported significant anti-tumour activity of dacomitinib in gefitinib-resistant lung cancer as well as breast cancer cell lines which are resistant to trastuzumab and lapatinib (a dual HER2 and EGFR inhibitor)37, 38. In the present study, we examined the mechanistic activity of dacomitinib in chemoresistant EOC cells.

Results

Chemosensitivity of the EOC cell lines

The chemoresponsiveness of a panel of EOC cell lines to certain chemotherapeutics and targeted therapies were determined by MTT assay and are summarized in Table 1. These data show that OVCAR3, SKOV3 and A2780CP cells exhibit resistance to carboplatin, doxorubicin and cetuximab, as compared to A2780S and Caov4 cells (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Chemosensitivity of a panel of EOC cell lines to certain chemotherapeutics and targeted therapies.

| Chemosensitivity (IC50)a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | Cisplatin (μg/mL) | Carboplatin (μg/mL) | Paclitaxel (μg/mL) | Doxorubicin (ng/mL) | Vincristine (ng/mL) | Gemcitabine (ng/mL) | Erlotinib (μM) | Cetuximab (μg/mL) |

| OVCAR3 | 1.025 | 797.2 | 1.894 | 432.2 | >1000 | 153.9 | 64.13 | >100 |

| SKOV3 | 5.799 | 71.32 | 5.355 | 696.1 | >1000 | 24.14 | 113.6 | >100 |

| A2780CP | 1.145 | 50.61 | 1.358 | 598.9 | 37.01 | 26.56 | 10.30 | >100 |

| A2780S | 0.8634 | 4.594 | 0.2092 | 4.063 | 32.25 | 15.87 | 5.244 | 82.31 |

| Caov4 | 0.3427 | 2.661 | 0.1155 | 5.102 | 3.430 | 4.560 | 2.635 | 43.89 |

Data represent the average of IC50 values and were collected from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. IC50 is the concentration of drug that caused a 50% reduction in proliferation compared to the vehicle-treated cells.

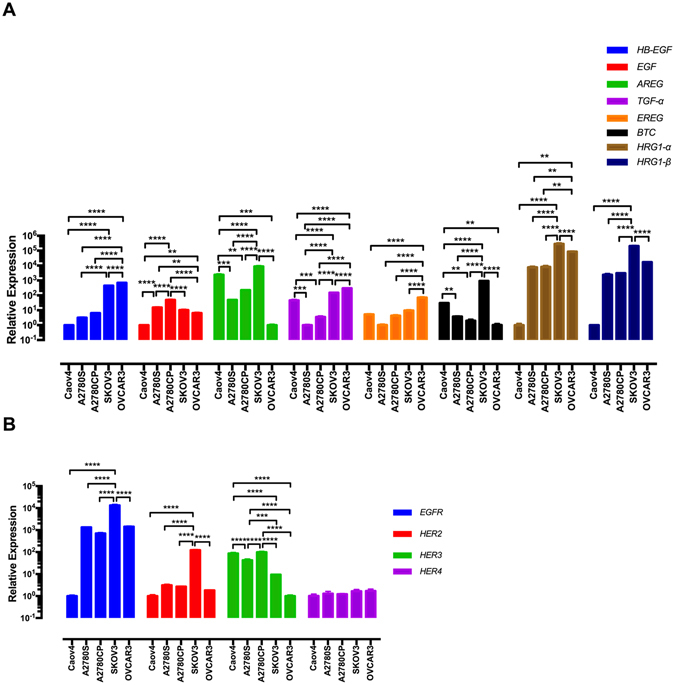

Expression of the ErbB family in the EOC cells

The expression of the ErbB family in chemoresistant versus sensitive EOC cells is not yet examined. To determine potential association between chemoresponsiveness and expression of the ErbB family, their relative expression was investigated by qRT-PCR. Using Tukey’s post hoc analysis, we found no difference in the expression of the ErbB family between the two groups of the EOC cells (Fig. 1A,B).

Figure 1.

Expression of the ErbB family in the EOC cells. (A,B) The mRNA levels of the ErbB family in the EOC cell lines were determined by qRT-PCR. The data were evaluated in triplicate and collected from three independent experiments. Gene expression levels were normalised to B2M in each cell line. Data were analysed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test and are shown as mean ± SD. Statistically significant values of *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001 were determined.

The ErbB family contributes to cisplatin resistance

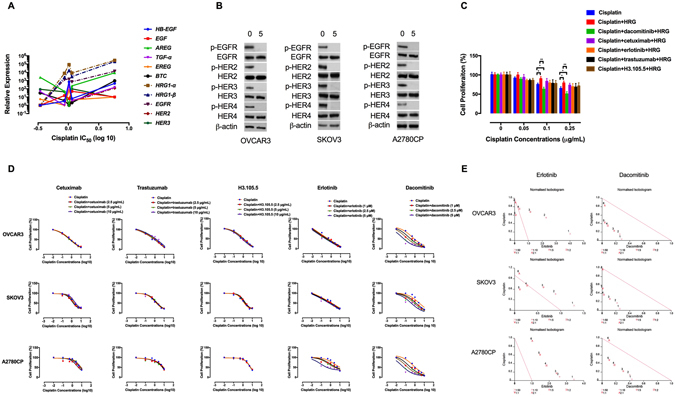

In an attempt to examine possible correlation between the mRNA levels of the ErbB family and chemoresponsiveness, we found that higher expression of HRG1-α and HRG1-β are significantly associated with resistance to cisplatin by Pearson’s correlation (Fig. 2A). The correlation coefficient (r) between the expression of HRG1-α and HRG1-β and cisplatin IC50 values is 0.9058 (P = 0.034) and 0.8997 (P = 0.037), respectively. In addition, our data demonstrated positive correlation between cisplatin resistance and higher expression of EGFR and HER2 (Fig. 2A). We found no significant association between the ErbB family expression and resistance to carboplatin, paclitaxel, doxorubicin, gemcitabine and erlotinib (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The ErbB family contributes to cisplatin resistance. (A) Correlation of expression of HRG1-α, HRG1-β, EGFR and HER2 with resistance to cisplatin. EOC cell lines with higher expression of HRG1-α, HRG1-β, EGFR and HER2 showed significantly higher cisplatin IC50 values. The correlation coefficient (r) between the expression of EGFR and HER2 and cisplatin concentrations was 0.917 (P = 0.0281) and 0.890 (P = 0.0341), respectively. (B) Dacomitinib inhibits ErbB activation. The effect of dacomitinib (5 μM) on ErbB activation was determined by Western blot analysis. Protein lysates were subjected to Western blotting and probed with the indicated antibodies. β-actin was used as the loading control. The blots are representative of three independent experiments with similar results. (C) The effects of the ErbB inhibitors on HRGβ-1-induced proliferation in cisplatin-treated Caov4 cells were shown by MTT assay. The cells were pre-treated with the anti-ErbB agents for 4 h, followed by treatment with HRGβ-1 for 48 h. (D) The effects of the ErbB inhibitors-cisplatin therapy on cell proliferation were investigated by MTT assay after 48 h of treatment and the data are shown by IC50 shift analysis. The concentrations of cisplatin were 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5 and 10 μg/mL. (E) Normalised isobolograms of combination of erlotinib (5 μM) and dacomitinib (5 μM) with cisplatin. The data were analysed using the CalcuSyn software. The connecting line represents additivity. Data points located below the line indicate a synergistic drug-drug interaction and data points above the line indicate an antagonistic interaction. The numbers under the isobolograms indicate the concentrations of the drugs in combination. Data shown represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Statistically significant values of *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 were determined compared with the control.

Expression of both HRG1-α and HRG1-β has been observed in 30–83% of EOC cell lines and tumour samples39. After binding to HRG, HER3 heterodimerises with the other ErbB receptors, which activates down-stream pro-survival pathways40. HRG1-β binds to HER3 with more affinity and induces greater activation of the ErbB receptors than HRG1-α41, 42. We therefore explored the effects of exogenous HRGβ-1 on proliferative response of the chemosensitive Caov4 cells to cisplatin. The resulting data show that pre-treatment with HRGβ-1 (10 ng/mL) decreased cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity, a process abrogated when the cells were pre-treated with dacomitinib but not single-targeted ErbB inhibitors including cetuximab, erlotinib, trastuzumab and H3.105.5 (a ligand-blocking anti-HER3 antibody) (Fig. 2C).

We next compared the effects of the ErbB inhibitors on potentiation of the anti-tumour effects of cisplatin in the chemoresistant EOC cells. Combination of dacomitinib with cisplatin had a synergistic effect on growth inhibition. In comparison, erlotinib-cisplatin therapy was antagonistic (Fig. 2D,E; Supplementary Tables 1, 2). Altogether, these findings suggest that the ErbB family might contribute to cisplatin resistance and a pan-ErbB inhibition strategy is required to augment cisplatin efficacy in the chemoresistant EOC cells.

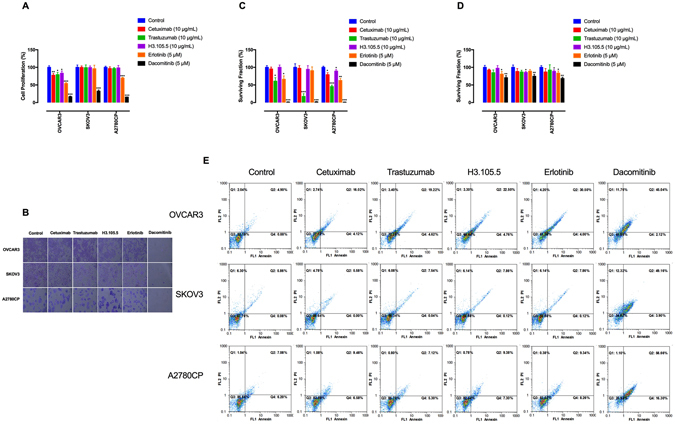

Dacomitinib inhibits cell viability and induces apoptosis

MTT assay was performed to estimate anti-proliferative effects of the anti-ErbB agents on the chemoresistant EOC cells. Treatment with dacomitinib inhibited cell growth (Fig. 3A,B). Clonogenic capacity represents the renewal potential and a long-term response of cells after treatment. The results of a colony formation assay demonstrate that both trastuzumab and dacomitinib reduced clonogenic survival (Fig. 3C). In immortalized cells, detachment from the extracellular matrix induces anoikis, a special type of apoptosis43. Acquisition of resistance to anoikis is a prerequisite for EOC cells to survive in ascites before forming metastatic foci44. Our data show that dacomitinib diminished anoikis resistance (Fig. 3D). Moreover, dacomitinib but not the single-targeted agents induced apoptotic cell death, as demonstrated by Annexin V staining (Fig. 3E). These data suggest that dacomitinib had stronger anti-proliferative efficacy compared to the single-targeted ErbB inhibitors (Fig. 3A–E).

Figure 3.

Dacomitinib inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis. (A) The effects of the ErbB inhibitors on cell proliferation were estimated by MTT assay after 48 h of treatment. (B) The effects of the anti-ErbB agents on cell viability were demonstrated by crystal violet staining. The cells were treated with the ErbB inhibitors for 48 h, then stained with crystal violet and imaged by an inverted microscope (images acquired at 10x magnification). (C) Clonogenic assay was conducted to evaluate the effects of the ErbB inhibitors on clonal proliferation. (D) Anoikis resistance assay was performed with cell culture on poly-HEMA–coated culture dishes for 48 h and the proportion of viable cells was measured by MTT assay. (E) The effects of the anti-ErbB agents on induction of apoptosis were determined by annexin V staining. Annexin V-positive cells are considered early apoptotic, whereas PI uptake indicates necrosis. Cells positive for both stains are considered late apoptotic. The graphs are representative of three independent experiments with similar outcomes. Data shown represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Statistically significant values of *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 were determined compared with the control.

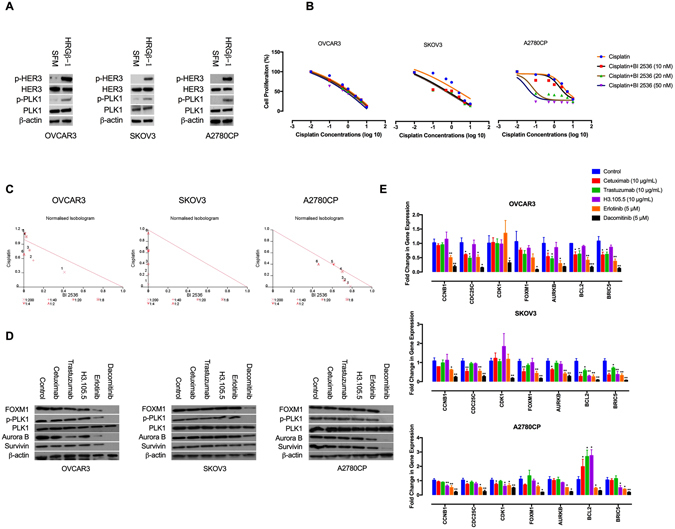

Dacomitinib inhibits PLK1-FOXM1 signalling

Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) is a serine/threonine protein kinase which plays a central role in mitotic progression and its elevated expression in EOC correlates with histological grade45. PLK1 induces forkhead box protein M1 (FOXM1), a member of FOX family of transcription factors that regulates expression of a wide range of genes such as PLK1, survivin (encoded by BIRC5), cyclin B1 (encoded by CCNB1) and Aurora kinase B (encoded by AURKB)46, 47. The FOXM1-target genes participate in different cellular functions including cell growth, metastatic dissemination and therapy resistance48, 49.

PLK1 has been shown to mediate resistance to chemotherapeutics including cisplatin50. To determine if the ErbB family activates PLK1 in the EOC cells, the cells were serum-starved for 24 h and then treated with HRGβ-1 (10 ng/mL) for 30 min. Immunoblotting analysis showed that HRGβ-1 stimulation resulted in activation of PLK1 (Fig. 4A). This is in consistency with previous reports that the ErbB receptors activate the PLK1-FOXM1 axis51, 52. We next sought if dacomitinib-induced sensitisation to cisplatin is through inhibition of PLK1 pathway. To achieve this, the cells were treated with cisplatin in combination with BI 2536, a highly selective PLK1 inhibitor. Our findings demonstrate that BI 2536 had synergistic activity with cisplatin on inhibition of cell growth (Fig. 4B,C; Table 2), suggesting that PLK1 blockade enhances sensitivity to cisplatin.

Figure 4.

Dacomitinib inhibits PLK1-FOXM1 pathway. (A) HRG/HER3 loop activates PLK1. The effects of HRGβ-1 on PLK1 activation was determined by Western blot analysis. Protein lysates from serum-starved and HRGβ-1-treated cells were subjected to Western blotting and probed with the indicated antibodies. The blots are representative of three independent experiments with similar outcomes. (B) PLK1 blockade increases cisplatin sensitivity. The effects of BI 2536-cisplatin therapy on cell proliferation were investigated by MTT assay and shown by IC50 shift analysis. The cultures were treated with BI 2536 (20 nM) and cisplatin (0.1, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5 and 10 μg/mL) for 48 h. (C) Normalised isobolograms of combination of BI 2536 and cisplatin. (D) The effects of cetuximab (10 μg/mL), trastuzumab (10 μg/mL), H3.105.5 (10 μg/mL), erlotinib (5 μM) and dacomitinib (5 μM) on PLK1-FOXM1 pathway and its down-stream targets were determined by Western blot analysis. The blots are representative of three independent experiments with similar outcomes. (E) The effects of the anti-ErbB agents on the expression of PLK1-FOXM1 targets genes were determined by qRT-PCR analysis. Data shown represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Statistically significant values of *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 were determined compared with the control. SFM, serum-free media; CCNB1, cyclin B1; CDC25C, cell division cycle 25C; CDK1, cyclin-dependent kinase 1; FOXM1, Forkhead box M1; AURKB, Aurora kinase B; BIRC5, survivin.

Table 2.

Combination index (CI) and dose reduction index (DRI) of BI 2536 and cisplatin combination in OVCAR3, SKOV3 and A2780CP cells.

| Concentrations | fa | CI | DRI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI 2536 (nM) | Cisplatin (μg/mL) | BI 2536 | Cisplatin | ||

| OVCAR3 | |||||

| 20 | 0.1 | 0.23 | 0.724 | 2.442 | 3.181 |

| 20 | 0.5 | 0.42 | 0.658 | 10.405 | 1.780 |

| 20 | 1 | 0.51 | 0.832 | 17.559 | 1.290 |

| 20 | 2.5 | 0.64 | 1.083 | 41.129 | 0.944 |

| 20 | 5 | 0.75 | 1.136 | 100.142 | 0.888 |

| 20 | 10 | 0.90 | 0.693 | 529.397 | 1.448 |

| SKOV3 | |||||

| 20 | 0.1 | 0.45 | 0.049 | 424.093 | 21.290 |

| 20 | 0.5 | 0.46 | 0.229 | 624.218 | 4.393 |

| 20 | 1 | 0.49 | 0.402 | 2972.447 | 2.491 |

| 20 | 2.5 | 0.62 | 0.640 | 7.8e + 005 | 1.562 |

| 20 | 5 | 0.79 | 0.627 | 5.39e + 009 | 1.594 |

| 20 | 10 | 0.84 | 0.944 | 1.83e + 011 | 1.060 |

| A2780CP | |||||

| 20 | 0.1 | 0.55 | 0.797 | 1.278 | 70.538 |

| 20 | 0.5 | 0.57 | 0.818 | 1.327 | 15.428 |

| 20 | 1 | 0.59 | 0.836 | 1.389 | 8.592 |

| 20 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 0.974 | 1.426 | 3.661 |

| 20 | 5 | 0.66 | 1.012 | 1.629 | 2.511 |

| 20 | 10 | 0.76 | 0.863 | 2.172 | 2.483 |

DRI represents the order of magnitude of dose reduction that is allowed in combination for a given degree of effect as compared with the dose of each drug alone. “fa” denotes fraction affected.

We therefore evaluated the effects of dacomitinib on PLK1-FOXM1 signalling. Our data show that dacomitinib, but not the single-targeted agents, inhibited p-PLK1 (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, dacomitinib reduced the mRNA and protein levels of FOXM1, survivin and Aurora kinase B. Conversely, the inhibitory effects of the single-targeted agents were marginal (Fig. 4D,E). Altogether, these data suggest that PLK1 blockade is a mechanism for dacomitinib-induced sensitisation to cisplatin and that a comprehensive ErbB inhibition strategy is required for blockade of PLK1-FOXM1 pathway and its down-stream targets.

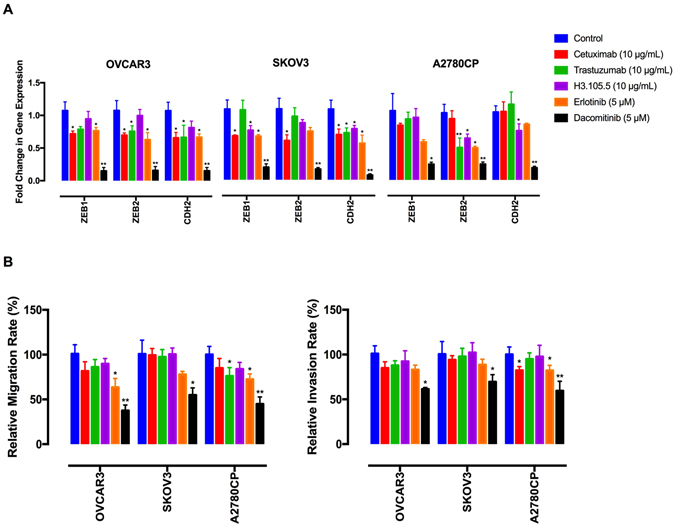

Dacomitinib reduces migration and invasion

Ovarian cancer metastasis includes tumour cells detachment from the primary site followed by their spread to the peritoneum and omentum53. The degree of peritoneal dissemination associates with poor prognosis54. Detachment of EOC cells from the primary site and their local invasion is driven by an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)55. EMT is triggered by down-regulation of cell adhesion molecules by transcriptional repressors ZEB1, ZEB2 and Snail56. It is thought that EMT contributes to loosening of intercellular adhesions and shedding of EOC cells into ascites57. We next determined the effects of dacomitinib on expression of the EMT markers ZEB1, ZEB2 and CDH2 (which encodes N-cadherin). The resulting data indicate that dacomitinib had stronger inhibitory effects on the expression of the EMT markers, as compared to the single-targeted agents (Fig. 5A). Moreover, these data show that dacomitinib hindered migration and invasion of the EOC cells through matrigel (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Dacomitinib inhibits migration and invasion. (A) The effects of the anti-ErbB agents on expression of EMT markers were determined by qRT-PCR analysis. (B) The effects of the ErbB inhibitors on cell migration and invasion. The cells were placed into 8-μm porous culture inserts, treated with the drugs and allowed to migrate for 48 h. The migrated cells on the lower surface of the inserts were quantified by crystal violet staining. For invasion assay, the cells were placed into matrigel-coated inserts and allowed to invade through the matrigel layer for 48 h. Data shown represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Statistically significant values of *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 were determined compared with the control.

Discussion

There is evidence that the ErbB signalling network contributes to chemoresistance in EOC. EGFR drives resistance to cisplatin through induction of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-258. HER2 promotes resistance to taxane chemotherapies and its depletion enhances chemosensitivity59. Moreover, activation of HER3 has been demonstrated to drive chemoresistance in EOC cells via activation of AKT pathway60. These findings suggest that the ErbB family is a potential therapeutic target in the chemoresistant EOC and its blockade might inhibit tumour growth and induce chemosensitisation61.

During ovarian carcinoma metastasis, epithelial cells lose E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell interactions, up-regulate N-cadherin and undergo EMT62. Evidence indicates that EMT correlates with a poor prognosis in EOC63, 64. Moreover, EMT is thought to drive a chemoresistant behaviour65, 66. Induction of EMT promotes peritoneal dissemination and reversing the EMTed phenotype is believed to be a novel strategy to hamper intraperitoneal metastasis67. Targeting signalling pathways contributing to EMT is a potential therapeutic approach in order to hinder invasiveness of EOC cells68. Both EGFR and HER2 downregulate E-cadherin expression, induce an EMTed phenotype and increase motility of EOC cells69, 70. The results of the present study suggest that blocking the ErbB receptors by dacomitinib is an effective strategy in order to reduce the expression of the EMT markers and hamper invasive capability of the chemoresistant EOC cells.

Single-targeted ErbB agents have shown minimum response in chemoresistant ECO patients26, 31, 71. Compensatory activation of the other ErbB receptors sustains the activation of common downstream pro-survival pathways72. Targeting all the ErbB receptors is therefore a more effective treatment strategy, especially when resistance to a single-targeted ErbB agent has occurred73. For instance, breast cancer patients who experienced tumour progression after treatment with trastuzumab have demonstrated response to the dual EGFR and HER2 inhibitor lapatinib74. Furthermore, cetuximab-resistant colorectal and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells are sensitive to pan-ErbB inhibitors75–77. In consistency, our data show that the inhibitory effects of the single-targeted ErbB inhibitors on viability and invasiveness of the chemoresistant EOC cells were marginal. Conversely, dacomitinib exerted pronounced anti-tumour activity, suggesting that it may have potential for treatment of the EOC patients who ultimately have developed resistance after initial response.

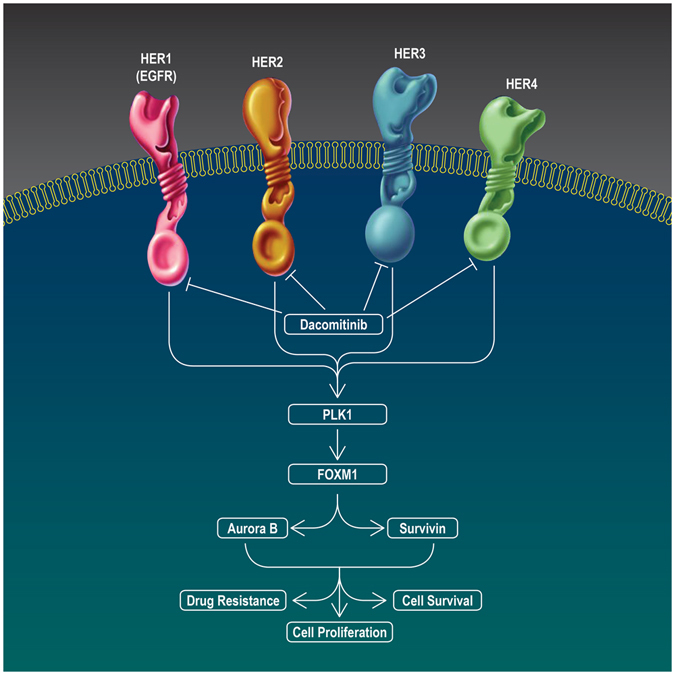

Taken together, the results of the present study provide new insight into the mechanistic activity of dacomitinib through inhibition of the PLK1-FOXM1 axis (Fig. 6). These findings also indicate that dacomitinib-mediated blockade of the ErbB receptors provides advantages over single-targeted ErbB inhibitors and thus offer a novel and promising treatment strategy to address chemoresistance in EOC. Further in vivo investigations are warranted to explore the anti-tumour activity of dacomitinib in therapy-resistant EOC.

Figure 6.

Schematic illustration of the anti-tumour effects of dacomitinib on the EOC cells. Dacomitinib inhibited cell growth, induced apoptosis and restored cisplatin sensitivity through blockade of the PLK1/FOXM1 axis and its downstream targets Aurora B and survivin.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and chemicals

Antibodies were obtained as follows: Aurora B (Abcam); EGFR, HER2, HER3 (clone 2F12) and HER3-neutralising monoclonal antibody (clone H3.105.5) (Millipore); p-EGFR (Tyr1068), p-HER2 (Tyr1248), p-HER3 (Tyr1289; clone 21D3), p-HER4 (Tyr1284; clone 21A9) and p-PLK1 (Thr210) (Cell Signalling Technology); HER4 (clone C-7), PLK1 (clone F-8), FOXM1 (clone C-20), survivin (clone FL-142) and β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Dacomitinib and BI 2536 (a specific inhibitor of polo-like kinase 1) were purchased from Adooq Bioscience (Irvine, CA, USA) and were dissolved in DMSO. The final concentrations of DMSO did not exceed than 0.1% [v/v] in all the treatments. Erlotinib (EGFR small molecule inhibitor) was obtained from Chemietek (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Cetuximab (a ligand-blocking anti-EGFR mAb), trastuzumab (anti-HER2 mAb), cisplatin and doxorubicin (DNA-damaging drugs), paclitaxel (a taxane inhibitor of microtubule disassembly), vincristine (a mitosis-blocking agent), carboplatin (an alkylating agent) and gemcitabine (a nucleoside analogue which inhibits DNA synthesis) were purchased from the pharmacy of Shariati hospital (Tehran, Iran). Poly-hydroxyethylmethacrylate polymer (poly-HEMA) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Recombinant HRGβ-1 was purchased from Peprotech.

Human ovarian carcinoma cell lines

Human ovarian carcinoma cell lines were obtained from National Cell Bank of Iran (NCBI, Tehran, Iran). These include A2780CP, A2780S, Caov4, OVCAR3 and SKOV3. All the cell lines were authenticated by STR profiling and were routinely checked for mycoplasma infection. Cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator and cultured according to NCBI recommendations.

Chemosensitivity assay

The EOC cells were seeded at 2 × 103 per well in 96-well plates and treated with the chemotherapeutics for 48 h. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay. Vehicle-treated cells were used as the control group. Chemosensitivity was shown as IC50 values calculated from full dose–response curves.

Median-effect analysis for treatment synergy

To determine the efficacy of combination of cisplatin with the anti-ErbB agents, the cells were treated with 0 to 10 μg/mL of cisplatin and different concentrations of the ErbB inhibitors for 48 h. Survival fractions in each treatment were determined by MTT assay and combination index (CI) was computed using the method developed by Chou and Talalay78 and the computer software CalcuSyn (Biosoft, Cambridge, UK). CI < 1, CI = 1 and CI > 1 represent synergism, additive effects and antagonism of the two drugs, respectively.

Crystal violet staining

The cells were plated at a density of 6 × 104 cells in 6-well plates and treated with the drugs for 48 h. The cultures were then washed with PBS, fixed with ice-cold methanol and stained with crystal violet (0.5% w/v). The images were acquired with an inverted microscope.

Colony formation assay

Single-cell suspensions were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 500 cells/well. Once adhered, the cells were treated with the desired concentrations of the drugs for 48 h. The plates were further incubated for 10 d and colonies were stained with 0.5% crystal violet and counted under an inverted microscope. Plating efficiency (PE) and survival fraction (SF) were calculated using the following formula: PE = number of colonies/number of cells seeded; SF = number of colonies/number of cells seeded × PE and plotted graphically to obtain survival curves.

Anoikis resistance assay

For anoikis evaluation, 96-well plates were coated with poly-HEMA (20 mg/mL in 95% ethanol) and dried in a tissue culture hood. The cells were trypsinised into a single cell suspension and seeded in poly-HEMA-coated plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well. The cell suspension cultures were treated with the desired concentrations of the drugs for 48 h. Cell viability was estimated by MTT assay.

Analysis of gene expression by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR

The quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis was performed on a LightCycler 96 instrument (Roche Molecular Diagnostics) using RealQ-PCR Master Mix kit (Ampliqon, Copenhagen, Denmark). The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 3. The target gene expression levels were normalised to beta-2-microglobulin (B2M) levels in the same reaction. For calculations, 2−ΔΔC T formula was used, with ΔΔCT = (CT target − CT B2M) experimental sample – (CT target − CT B2M) control samples, where CT is cycle threshold79.

Western blot analysis

The cells were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and 0.1% SDS) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay. A total of 50 to 100 μg of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Membrane Solutions, TX, USA). Membranes were blocked and blotted with the relevant antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were detected with a BM chemiluminescence detection kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). β-actin was used as the loading control. All antibody dilutions were 1:500 except for the β-actin antibody, which was used at a dilution of 1:5000.

Annexin V/PI staining

Cells were stained with PI and FITC-conjugated Annexin V, as provided by Annexin-V-FLUOS Staining Kit (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The results were analysed using a Partec PAS III flow cytometer (Partec GmbH) and WindowsTM FloMax software (Partec).

Cell migration and invasion

Transwell cell migration and invasion assays were carried out as described earlier80.

Statistical analysis

All data were evaluated in triplicate against vehicle-treated control cells and collected from three independent experiments. Data were graphed and analysed by GraphPad Prism Software 7.0a using one-way ANOVA and the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from Haematology/oncology and Stem Cell Transplantation Research Centre, Shariati hospital, School of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Author Contributions

M.M. designed the research; M.M., G.Z., F.M., A.P., G.S., A.Z., S.M., F.E., H.E., F.B., Z.S., Z.A. and H.Y. conducted the research; M.M., R.G., L.D., D.B., A.R.D., J.T., K.A. and A.G. analysed the data; M.M. wrote the paper; S.H.G. had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Majid Momeny and Ghazaleh Zarrinrad contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-04147-0

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannistra SA. Cancer of the ovary. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2519–2529. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korkmaz T, Seber S, Basaran G. Review of the current role of targeted therapies as maintenance therapies in first and second line treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer; In the light of completed trials. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2016;98:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dinh P, Harnett P, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Awada A. New therapies for ovarian cancer: cytotoxics and molecularly targeted agents. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2008;67:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrandina G, et al. Phase III trial of gemcitabine compared with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in progressive or recurrent ovarian cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:890–896. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.6606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burger RA, Sill MW, Monk BJ, Greer BE, Sorosky JI. Phase II trial of bevacizumab in persistent or recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer or primary peritoneal cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:5165–5171. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baselga J, Swain SM. Novel anticancer targets: revisiting ERBB2 and discovering ERBB3. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2009;9:463–475. doi: 10.1038/nrc2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arteaga CL, Engelman JA. ERBB receptors: from oncogene discovery to basic science to mechanism-based cancer therapeutics. Cancer cell. 2014;25:282–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tebbutt N, Pedersen MW, Johns TG. Targeting the ERBB family in cancer: couples therapy. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2013;13:663–673. doi: 10.1038/nrc3559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheng Q, Liu J. The therapeutic potential of targeting the EGFR family in epithelial ovarian cancer. British journal of cancer. 2011;104:1241–1245. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gui T, Shen K. The epidermal growth factor receptor as a therapeutic target in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer epidemiology. 2012;36:490–496. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garces ÁHI, Dias MSF, Paulino E, Ferreira CGM, de Melo AC. Treatment of ovarian cancer beyond chemotherapy: Are we hitting the target? Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2015;75:221–234. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2581-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lassus H, et al. Gene amplification, mutation, and protein expression of EGFR and mutations of ERBB2 in serous ovarian carcinoma. Journal of molecular medicine. 2006;84:671–681. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudson LG, Zeineldin R, Silberberg M, Stack MS. Activated epidermal growth factor receptor in ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;149:203–226. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-98094-2_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Psyrri A, et al. Effect of epidermal growth factor receptor expression level on survival in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11:8637–8643. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berchuck A, et al. Overexpression of HER-2/neu is associated with poor survival in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer research. 1990;50:4087–4091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujimura M, et al. HER2 is frequently over-expressed in ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma: possible novel treatment modality using recombinant monoclonal antibody against HER2, trastuzumab. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2002;93:1250–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2002.tb01231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leng J, Lang J, Shen K, Guo L. Overexpression of p53, EGFR, c-erbB2 and c-erbB3 in endometrioid carcinoma of the ovary. Chinese medical sciences journal=Chung-kuo i hsueh k’o hsueh tsa chih/Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. 1997;12:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ocana A, et al. HER3 overexpression and survival in solid tumors: a meta-analysis. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2013;105:266–273. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies S, et al. High incidence of ErbB3, ErbB4, and MET expression in ovarian cancer. International journal of gynecological pathology: official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists. 2014;33:402–410. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lafky JM, Wilken JA, Baron AT, Maihle NJ. Clinical implications of the ErbB/epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor family and its ligands in ovarian cancer. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2008;1785:232–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Granados ML, Hudson LG, Samudio-Ruiz SL. Contributions of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor to Acquisition of Platinum Resistance in Ovarian Cancer Cells. PloS one. 2015;10:e0136893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song X, Sun K, Hu J, Zhou J. Suppression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 via interference increases the chemosensitivity of ovarian carcinoma. Oncology letters. 2016;11:3028–3032. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pradeep S, et al. Hematogenous metastasis of ovarian cancer: rethinking mode of spread. Cancer cell. 2014;26:77–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Secord AA, et al. Phase II trial of cetuximab and carboplatin in relapsed platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer and evaluation of epidermal growth factor receptor expression: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecologic oncology. 2008;108:493–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schilder RJ, et al. Phase II study of gefitinib in patients with relapsed or persistent ovarian or primary peritoneal carcinoma and evaluation of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and immunohistochemical expression: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11:5539–5548. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vergote IB, et al. Randomized phase III study of erlotinib versus observation in patients with no evidence of disease progression after first-line platin-based chemotherapy for ovarian carcinoma: a European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Gynaecological Cancer Group, and Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup study. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:320–326. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siwak DR, et al. Targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor in epithelial ovarian cancer: current knowledge and future challenges. Journal of oncology. 2010;2010:568938. doi: 10.1155/2010/568938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blank SV, et al. Erlotinib added to carboplatin and paclitaxel as first-line treatment of ovarian cancer: a phase II study based on surgical reassessment. Gynecologic oncology. 2010;119:451–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Annunziata CM, et al. Vandetanib, designed to inhibit VEGFR2 and EGFR signaling, had no clinical activity as monotherapy for recurrent ovarian cancer and no detectable modulation of VEGFR2. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16:664–672. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bookman MA, Darcy KM, Clarke-Pearson D, Boothby RA, Horowitz IR. Evaluation of monoclonal humanized anti-HER2 antibody, trastuzumab, in patients with recurrent or refractory ovarian or primary peritoneal carcinoma with overexpression of HER2: a phase II trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:283–290. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordon MS, et al. Clinical activity of pertuzumab (rhuMAb 2C4), a HER dimerization inhibitor, in advanced ovarian cancer: potential predictive relationship with tumor HER2 activation status. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:4324–4332. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzales AJ, et al. Antitumor activity and pharmacokinetic properties of PF-00299804, a second-generation irreversible pan-erbB receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1880–1889. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janne PA, et al. Phase I dose-escalation study of the pan-HER inhibitor, PF299804, in patients with advanced malignant solid tumors. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:1131–1139. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramalingam SS, et al. Randomized phase II study of dacomitinib (PF-00299804), an irreversible pan-human epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor, versus erlotinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:3337–3344. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.9433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramalingam SS, et al. Dacomitinib versus erlotinib in patients with advanced-stage, previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (ARCHER 1009): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1369–1378. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70452-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Engelman JA, et al. PF00299804, an irreversible pan-ERBB inhibitor, is effective in lung cancer models with EGFR and ERBB2 mutations that are resistant to gefitinib. Cancer research. 2007;67:11924–11932. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalous O, et al. Dacomitinib (PF-00299804), an irreversible Pan-HER inhibitor, inhibits proliferation of HER2-amplified breast cancer cell lines resistant to trastuzumab and lapatinib. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:1978–1987. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilmour LM, et al. Neuregulin expression, function, and signaling in human ovarian cancer cells. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2002;8:3933–3942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tzahar E, et al. A hierarchical network of interreceptor interactions determines signal transduction by Neu differentiation factor/neuregulin and epidermal growth factor. Molecular and cellular biology. 1996;16:5276–5287. doi: 10.1128/MCB.16.10.5276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Breuleux M. Role of heregulin in human cancer. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS. 2007;64:2358–2377. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7120-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiss, F. U., Wallasch, C., Campiglio, M., Issing, W. & Ullrich, A. Distinct characteristics of heregulin signals mediated by HER3 or HER4. Journal of cellular physiology173, 187–195, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Chiarugi P, Giannoni E. Anoikis: a necessary death program for anchorage-dependent cells. Biochemical pharmacology. 2008;76:1352–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sher I, Adham SA, Petrik J, Coomber BL. Autocrine VEGF-A/KDR loop protects epithelial ovarian carcinoma cells from anoikis. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2009;124:553–561. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takai N, et al. Expression of polo-like kinase in ovarian cancer is associated with histological grade and clinical stage. Cancer letters. 2001;164:41–49. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(00)00703-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fu Z, et al. Plk1-dependent phosphorylation of FoxM1 regulates a transcriptional programme required for mitotic progression. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1076–1082. doi: 10.1038/ncb1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laoukili J, et al. FoxM1 is required for execution of the mitotic programme and chromosome stability. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:126–136. doi: 10.1038/ncb1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koo CY, Muir KW, Lam EW. FOXM1: From cancer initiation to progression and treatment. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2012;1819:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu N, et al. FoxM1 mediated resistance to gefitinib in non-smallcell lung cancer cells. Acta pharmacologica Sinica. 2012;33:675–681. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tyagi S, et al. Polo-like kinase1 (Plk1) knockdown enhances cisplatin chemosensitivity via up-regulation of p73α in p53 mutant human epidermoid squamous carcinoma cells. Biochemical pharmacology. 2010;80:1326–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McGovern UB, et al. Gefitinib (Iressa) represses FOXM1 expression via FOXO3a in breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:582–591. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Francis RE, et al. FoxM1 is a downstream target and marker of HER2 overexpression in breast cancer. International journal of oncology. 2009;35:57–68. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lengyel E. Ovarian cancer development and metastasis. The American journal of pathology. 2010;177:1053–1064. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blechschmidt K, et al. The E-cadherin repressor Snail is associated with lower overall survival of ovarian cancer patients. British journal of cancer. 2008;98:489–495. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahmed N, Thompson EW, Quinn MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal interconversions in normal ovarian surface epithelium and ovarian carcinomas: an exception to the norm. Journal of cellular physiology. 2007;213:581–588. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elloul S, et al. Snail, Slug, and Smad‐interacting protein 1 as novel parameters of disease aggressiveness in metastatic ovarian and breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:1631–1643. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Symowicz J, et al. Engagement of collagen-binding integrins promotes matrix metalloproteinase-9–dependent E-cadherin ectodomain shedding in ovarian carcinoma cells. Cancer research. 2007;67:2030–2039. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yue P, et al. Hyperactive EGF receptor, Jaks and Stat3 signaling promote enhanced colony-forming ability, motility and migration of cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene. 2012;31:2309–2322. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ueno NT, et al. E1A-mediated paclitaxel sensitization in HER-2/neu-overexpressing ovarian cancer SKOV3.ip1 through apoptosis involving the caspase-3 pathway. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2000;6:250–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bezler M, Hengstler JG, Ullrich A. Inhibition of doxorubicin-induced HER3-PI3K-AKT signalling enhances apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells. Molecular oncology. 2012;6:516–529. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chan JK, et al. Suppression of ovarian cancer cell tumorigenicity and evasion of Cisplatin resistance using a truncated epidermal growth factor receptor in a rat model. Cancer research. 2005;65:3243–3248. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ahmed N, Thompson EW, Quinn MA. Epithelial–mesenchymal interconversions in normal ovarian surface epithelium and ovarian carcinomas: an exception to the norm. Journal of cellular physiology. 2007;213:581–588. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoshihara K, et al. Gene expression profiling of advanced‐stage serous ovarian cancers distinguishes novel subclasses and implicates ZEB2 in tumor progression and prognosis. Cancer science. 2009;100:1421–1428. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01204.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang RY, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal gene expression signature defines clinically relevant subtypes in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer research. 2012;72:2979–2979. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2012-2979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park S-H, Cheung LW, Wong AS, Leung PC. Estrogen regulates Snail and Slug in the down-regulation of E-cadherin and induces metastatic potential of ovarian cancer cells through estrogen receptor α. Molecular endocrinology. 2008;22:2085–2098. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rosanò L, et al. Acquisition of chemoresistance and EMT phenotype is linked with activation of the endothelin A receptor pathway in ovarian carcinoma cells. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17:2350–2360. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huang RY, Chung VY, Thiery JP. Targeting pathways contributing to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in epithelial ovarian cancer. Curr Drug Targets. 2012;13:1649–1653. doi: 10.2174/138945012803530044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yun-Ju Huang R, Yee Chung V, Paul Thiery J. Targeting pathways contributing to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in epithelial ovarian cancer. Current drug targets. 2012;13:1649–1653. doi: 10.2174/138945012803530044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Comamala M, et al. Downregulation of cell surface CA125/MUC16 induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and restores EGFR signalling in NIH: OVCAR3 ovarian carcinoma cells. British journal of cancer. 2011;104:989–999. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cheng J-C, Qiu X, Chang H-M, Leung PC. HER2 mediates epidermal growth factor-induced down-regulation of E-cadherin in human ovarian cancer cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2013;434:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kaye SB, et al. A randomized phase II study evaluating the combination of carboplatin-based chemotherapy with pertuzumab versus carboplatin-based therapy alone in patients with relapsed, platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:145–152. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Britten CD. Targeting ErbB receptor signaling: a pan-ErbB approach to cancer. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2004;3:1335–1342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kruser TJ, Wheeler DL. Mechanisms of resistance to HER family targeting antibodies. Experimental cell research. 2010;316:1083–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Geyer CE, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2733–2743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ather F, et al. Dacomitinib, an irreversible Pan-ErbB inhibitor significantly abrogates growth in head and neck cancer models that exhibit low response to cetuximab. PloS one. 2013;8:e56112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Khelwatty SA, Essapen S, Seddon AM, Fan Z, Modjtahedi H. Acquired resistance to anti-EGFR mAb ICR62 in cancer cells is accompanied by an increased EGFR expression, HER-2/HER-3 signalling and sensitivity to pan HER blockers. British journal of cancer. 2015;113:1010–1019. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Francis DM, et al. Pan-HER Inhibitor Augments Radiation Response in Human Lung and Head and Neck Cancer Models. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2016;22:633–643. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chou TC. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer research. 2010;70:440–446. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Momeny M, et al. Blockade of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors by tivozanib has potential anti-tumour effects on human glioblastoma cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44075. doi: 10.1038/srep44075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Momeny M, et al. Heregulin-HER3-HER2 signaling promotes matrix metalloproteinase-dependent blood-brain-barrier transendothelial migration of human breast cancer cell lines. Oncotarget. 2015;6:3932–3946. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.