Abstract

Purpose

Early perceived pubertal timing and faster maturation have been linked to increased risk of adolescent substance use, particularly for girls, but the mechanisms underlying this association are not well understood. We sought to replicate and extend findings from Westling et al. (2008) showing that peer deviance mediates the link between early puberty and substance use with stronger pathways in the context of low parental knowledge of adolescents’ whereabouts and activities.

Methods

Participants (n=1,023; 52% female; 24% non-White; 12% Hispanic) were recruited through middle schools. Pubertal timing and tempo were derived from repeated measures of perceived pubertal development. Specific sources of parental knowledge included child disclosure and parental solicitation. Two measures of peer deviance (problem behaviors and substance use) were obtained. Use of any substances (alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, other illicit drugs) was coded from all assessments.

Results

For girls, earlier pubertal timing was associated with higher likelihood of substance use but only in girls who disclosed less. For boys, slower tempo predicted greater substance use, equally across parental knowledge groups. Pubertal timing and tempo were generally not associated with peer deviance; however, we detected a significant indirect effect such that peer problem behavior mediated the association between girls’ early pubertal timing and substance use. Parental knowledge did not moderate this effect.

Conclusions

Peer deviance was not strongly supported as a mechanism underlying atypical pubertal risk for substance use (supported in one of eight models). Parental knowledge appears to serve as a contextual amplifier of pubertal risk, independent of peer influences.

Keywords: puberty, pubertal timing, pubertal tempo, substance use, peer, parental knowledge

The pubertal transition is a key biological and social process of change during adolescence, and is associated with changes in social environments and increased behavior problems, including substance use (1). Complex models for how puberty and social environments together impact the development of substance use have become more common in the literature, but are rarely replicated and thus may be sample-specific. The goal of this study is to replicate and extend one such model presented by Westling and colleagues (2008), described in more detail below.

Findings regarding the associations between pubertal timing and substance use are mixed. Early and faster pubertal maturation has been linked to increased risk for substance use in adolescence, particularly in girls (2–4), although sometimes later and/or slower pubertal maturation marks increased risk for substance use in boys (5–7). According to the developmental readiness hypothesis, youth with earlier pubertal timing may be emotionally or physiologically unprepared for the physical and social changes associated with puberty and therefore be at greater risk for mental health problems, substance initiation, and substance use (8, 9). Early developing youth may also seek out or be invited into friend groups who are more mature and engage in more mature activities (e.g., substance use). According to the maturation compression hypothesis (10), these potential consequences of earlier timing may also develop when pubertal milestones are experienced in a compressed timeframe (faster tempo), as the timing of subsequent milestones occurs earlier and earlier. Yet, later timing and/or slower tempo may also index risk: youth (especially boys) who appear younger for longer periods of time relative to their peers may engage in more mature activities (e.g., substance use) to compensate for their younger physical appearance in an attempt to increase status. Further, experimental studies in animals show that early initiation of substance use may delay or slow pubertal maturation in boys, with some supporting evidence in humans (6, 11). Here, we examine both timing and tempo of pubertal maturation in relation to substance use in boys and girls.

There has been increasing interest in understanding how contextual factors may mediate, strengthen, or weaken the association between atypical pubertal maturation and substance use. Two of the most salient contextual factors are peer influences, specifically peer deviance and peer substance use; and parenting, specifically the extent of parents’ knowledge of adolescents’ whereabouts and activities (12–14). Peer characteristics are often considered as a mediator of puberty-substance use associations: peer deviance, risky behaviors, and perceived and actual substance use of peers can mediate associations between pubertal risk and substance use (15–17). Parental knowledge has been shown to moderate associations of pubertal risk and substance use such that lower levels of knowledge exacerbate (and higher levels diminish) associations between atypical pubertal maturation and substance use (13), a finding we observed in our earlier work in this sample (5). Further, low parental knowledge has also been shown to exacerbate the influence of peer deviance on substance use (18, 19). Together, this literature suggests that parents and peers together may be implicated in how adolescents’ pubertal maturation marks risk for substance use (19, 20).

Westling and colleagues (2008) proposed and tested a moderated mediation pathway such that peer deviance (in 6th/7th grade) would mediate the link between early puberty (in 4th/5th grade for girls, 6th/7th grade for boys) and substance use (alcohol and cigarette use in 7th/8th grade), and that both mediation pathways (to and from peer deviance) would be strengthened in the context of low parental knowledge (in 6th/7th grade). For boys, early pubertal timing predicted alcohol use only in the context of low/average (not high) parental knowledge. For girls, affiliation with deviant peers partially mediated the association of early pubertal timing with cigarette use, and parental knowledge moderated the association of early pubertal timing and affiliation with deviant peers such that mediation was found only for girls in the context of low parental knowledge. Our goal was to replicate and extend findings from Westling et al. (2008). We expand upon Westling et al., (2008) by using a larger sample, including tempo, and timing*tempo interactions in addition to timing, and investigating specific sources of parental knowledge (child disclosure and parental solicitation) as moderators of, and aspects of peer deviance (problem behaviors and substance use) as mechanisms of associations of pubertal maturation and substance use.

Present Study

We hypothesized that peer deviance would mediate the association of pubertal timing and tempo with substance use, and that parental knowledge would moderate these pathways, given evidence that parental knowledge moderates associations of pubertal risk and substance use (5), and peer deviance and substance use (19, 20), and to replicate the pattern of results from Westling et al., (2008). Given our earlier findings (5), we tested distinct communicative sources of parental knowledge (child disclosure and parental solicitation). Boys and girls were examined separately given prior evidence of sex differences in pubertal maturation and associations of puberty with peer, parenting, and substance use outcomes (13).

Method

Participants

Study participants were 1,023 students recruited from six middle schools (52% female; 24% non-White; 12% Hispanic); at time of enrollment, students were equally distributed across 6th (33%), 7th (32%), and 8th (35%) grades. See Jackson, Colby (21) for study/procedure details. The sample was largely representative of the schools from which it was drawn with regard to sex and grade distribution, although our sample is more racially diverse but less disadvantaged than the school populations (http://infoworks.ride.ri.gov/).

Procedure

Participants were recruited through schools; study information and consent forms were both distributed at schools and mailed to students’ homes. Consent forms were returned to schools by 39% of students; 65% of those returned allowing for participation. Interested youth who had written informed parental consent (88%) attended a two-hour inperson group orientation that included a 45-minute computerized baseline survey as well as explanation of study procedures.

Over four years, participants completed a series of web-based follow-up surveys. The first five surveys were administered on a semi-annual basis (6 months apart over 2 years); the sixth was administered one year later. At that point the survey design was modified as part of a new funding cycle, and assessments were administered on a quarterly basis (data collection is ongoing). The present study draws from data from the first six assessments (W1–6; MageW1=12.66, SD=0.94; MageW2=13.15, SD=0.93; MageW3=13.64, SD=0.92; MageW4=14.16, SD=0.92; MageW5=14.64, SD=0.93; MageW6=15.63, SD=0.91), and a seventh assessment (W7; Mage=16.61, SD=0.89) taken from the quarterly survey (the timing of which varied across school cohort) that fell one year after W6.

Response rates for a given semi-annual survey ranged from 92% (W2) to 79% (W7). Over 76% of the sample had valid data on substance use at W7 (n=785). Kruskal-Wallace tests showed that youth with and without valid substance use data did not differ on most demographic variables (e.g. parents’ marital status, income, mother age, qualifying for free/reduced school lunches), p’s>.05. Exceptions were that youth who had slightly younger fathers and whose parents had lower education were less likely to have substance use data (χ2=4.46–9.95, p’s<.05). Youth who disclosed less to parents at W1 were less likely to have substance use data (χ2=15.72, p<.05), but there were no differences between youth with and without valid substance use data on other study-related variables. All procedures were approved by the university institutional review board and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from NIAAA to preserve participant confidentiality.

Measures

Pubertal Timing and Tempo

Children’s perceived pubertal development was assessed at each Wave using the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS, 22), which assesses secondary sex characteristic development by youth self-report. As typically done, average scores across 5 items were used in data analysis. Retention was good; 85% of the sample had at least 5 (of 7) assessments of the PDS (n=869); only 9% of the sample was missing 4+ assessments (n=97).

Perceived pubertal timing and tempo scores were obtained from the repeated measures of the PDS and age (measured continuously) using logistic growth curves (23, 24); see Marceau, Abar (5) for equation and model details. The estimates for individuals’ perceived timing [intercept, age at the midpoint of development, consistent with prior studies] and tempo of puberty [change, in number of stages per year at the midpoint of development] were extracted from the models to be used in hypothesis testing. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. The majority of the sample had an estimated age at mid-puberty earlier than their age at the W6 assessment (>94%); few youth had an estimated age at mid-puberty later than their age at the W6 assessment (5.5% of girls, 3.8% of boys). Values for timing and tempo of puberty were set to missing for those individuals who reached the midpoint of puberty later than their W6 assessment in order to maintain fidelity of temporal sequence in hypothesis testing.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for study variables

| Boys | Girls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pubertal Maturation (midpoint of development) |

M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Timing | 13.68 | 0.85 | 12.27 | 1.48 | ||

| Tempo | 0.40 | 0.19 | 0.42 | 0.21 | ||

| Parental Knowledge (W6) | M | SD | % in ‘high’ category | M | SD | % in ‘high’ category |

| Child Disclosure | 3.64 | 0.86 | 40% | 3.63 | 0.93 | 41% |

| Parental Solicitation | 3.01 | 1.07 | 35% | 3.14 | 1.13 | 43% |

| Peer Deviance (W6) | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range |

| Peer Problem Behaviors | 0.69 | 1.56 | 0–10 | 0.97 | 1.78 | 0–11 |

| Peer Substance Use | 0.56 | 1.22 | 0–6 | 0.94 | 1.50 | 0–6 |

| Adolescent Substance Use (by W7) | N ‘yes’ | N ‘no’ | % initiated | N ‘yes’ | N ‘no’ | % initiated |

| Any Substance Use | 145 | 199 | 42% | 255 | 185 | 58% |

Note. Adolescent substance use reflects ever/lifetime use.

Parental Knowledge

Specific sources of parental knowledge were assessed using youth self-report on the Parental Knowledge scale from Kerr and Stattin (25) at W6. Five-point (Never-Sometimes-Half the time-More than half-Always) scales corresponding to child disclosure (e.g., how much the adolescent tells parents of his/her activities; 5 items, α=.74) and parental solicitation (e.g., how much parents ask about adolescent’s activities; 5 items, α=.88) were correlated r=.61. We dichotomized each knowledge variable using mean splits for multiple-group moderation analyses.

Peer Deviance

Peer deviance was measured at W6 using a set of 19 binary items assessing past 12-month deviant behavior of respondents’ close friends, taken from several sources (26–28). We computed two count indicators, one including 6 peer substance use items (α=.81), and the other including 13 peer problem behavior items (e.g., cheated on tests in school; vandalized private property; used or threatened to use a weapon, α=.80) that were correlated r=.58. Scores were skewed, and thus log-transformed to normalize.

Substance Use

We scored whether the respondent reported ever using any substance by W7. For girls, 58% reported ever use of any substance. Specifically, 52% reported having a full drink, 34% reported heavy drinking (3+ drinks in an occasion), 30% reported marijuana use, 4% reported use of other drugs, 16% reported smoking at least a puff. For boys, 42% reported ever use of any substance. Specifically, 37% reported having a full drink, 24% reported heavy drinking (3+ drinks in an occasion) 15% reported marijuana use, 3% reported use of other drugs, 19% reported smoking at least a puff. Any substance use (SU) was examined as the primary outcome. However, given sufficient baserates for drinking, heavy drinking, puffing a cigarette, and marijuana use, we also conducted sensitivity analyses with each of these outcomes to determine whether the use of one or more specific substance(s) drove the findings.

Analytic Strategy

Hypotheses were tested using a series of multiple-group (low and high knowledge) path models in which timing, tempo, and timing*tempo predicted peer deviance, and then peer deviance, timing, tempo, and timing*tempo predicted SU, using Mplus V7.3 (29). Additionally, age and cohort were entered as controls for peer deviance and SU. A weighted least squares mean variances estimator was used because SU was categorical. Missing data was accommodated using fullinformation maximum likelihood. Four models were run within each gender, including 1) child disclosure as the grouping (moderator) variable, and peer problem behavior as the peer deviance (mediator) variable, 2) child disclosure as the moderator, and peer substance use as the mediator, 3) parental solicitation as the moderator, and peer problem behavior as the mediator, 4) parental solicitation as the moderator, and peer substance use as the mediator.

Indirect effects from timing, tempo, and timing*tempo to SU via peer deviance were tested using the MODEL INDIRECT command which utilizes the delta method to test significance of the mediated effect (30). In each multiplegroup analysis, we first tested a model where high and low knowledge groups were allowed to vary on path estimates, means and variances (results in Tables). Then we systematically tested models in which each hypothesis-testing path estimate was constrained to be equal across high and low knowledge groups, one at a time. If the constrained model showed a significant decrement in model fit, then we concluded that parental knowledge moderated that pathway. Finally, we constructed a “most parsimonious” model wherein paths that could be constrained to be equal across high and low knowledge groups were constrained, but those that differed significantly were allowed to vary (results in Figures). In all cases the most parsimonious model fit the data well, and not worse than the unconstrained model based on χ2 difference tests (using the DIFFTEST command). Only findings important for hypotheses are discussed in text.

Results

Correlations (Supplemental Table) showed that timing and tempo of puberty were generally not associated with peer deviance for boys or girls, r’s=−.06–.02, p’s>.05. Early timing, r=−.12, and faster tempo, r=.11, of puberty was associated with more child disclosure for boys, p’s>.05, and slower tempo of puberty was associated with higher rates of SU, r’s<−.12, p’s<.05, except puffing cigarettes, r=−.04, p’s>.05. For boys, peer problem behaviors and peer SU were associated with less child disclosure, r’s<−.21, p’s<.05. For girls, faster tempo of puberty was associated with more child disclosure and parental solicitation, r’s>.13, p’s<.05, and earlier timing of puberty was associated with SU across all measures, r’s<−.12, p’s<.05. Peer problem behavior and SU were associated with less child disclosure and parental solicitation, r’s<−.15, p’s<.05. Timing and tempo of puberty were associated for girls, r=.50, but not boys, r=.02.

Boys

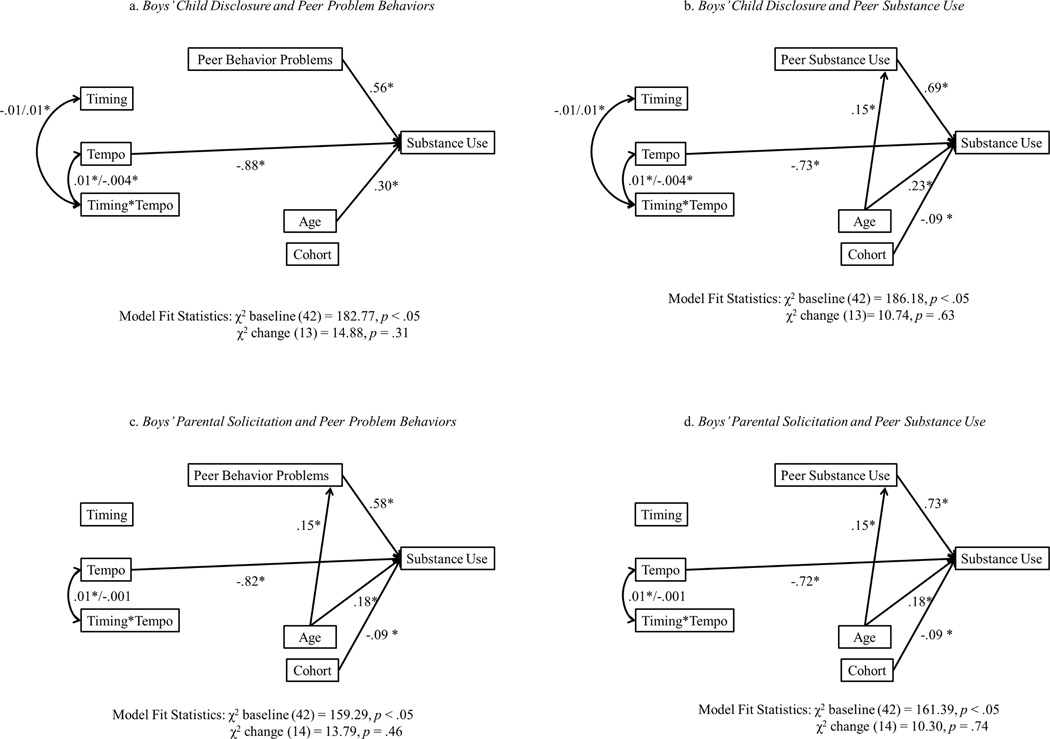

For boys, none of the hypothesis-related paths differed for low versus high child disclosure groups (Figure 1a, 1b; Table 2, top panel) or for low versus high parental solicitation groups (Figures 1c, 1d; Table 2, bottom panel). Peer problem behaviors, peer SU, and slower tempo each predicted higher likelihood of SU, equally in high and low child disclosure and parental solicitation groups. However, consistent with the correlations, pubertal measures did not predict peer deviance. Thus, our tests of moderation and mediation did not yield hypothesized effects.

Figure 1. Most Parsimonious Models for Boys.

Unstandardized parameter estimates from the best-fitting, most parsimonious model, wherein all paths that could be constrained to equality across high and low knowledge groups were constrained, are presented (hence, the parameter estimates may differ somewhat from the results for the full model presented in Tables). Only significant paths are depicted. Results from all four models for boys are presented: models including child disclosure as a moderator are presented in the top panel (1a, 1b), and models including parental solicitation as a moderator are presented in the bottom panel (1c, 1d). Models including peer behavior problems as the measure of peer deviance are presented on the left (1a, 1c) and models including peer substance use as the measure of peer deviance are presented on the right (1b, 1d). When paths show significant moderation, the low disclosure group is on the left of the / and the high disclosure group is on the right. * p < .05. Paths with a single estimate were constrained across groups without a decrement in model fit. Timing and tempo were assessed from repeated measures across all waves (the mid-point of development occurring prior to W6). Peer deviance and parental knowledge measures were assessed at W6, and substance use was assessed at W7.

Table 2.

Parameters for Models of Puberty, Parental Knowledge (Child Disclosure and Parental Solicitation), Peer Deviance (Problem Behaviors and Peer Substance Use), and Substance Use for Boys.

| Outcome | Puberty | Peer Problem Behavior Model | Peer Substance Use Model | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tempo | Timing × Tempo | Peer Deviance | Substance Use | Peer Deviance | Substance Use | |||||||

| CHILD DISCLOSURE AS MODERATOR | ||||||||||||

| Predictor | Low CD |

High CD |

Low CD |

High CD |

Low CD |

High CD |

Low CD |

High CD |

Low CD |

High CD |

Low CD |

High CD |

| Timing | .00 (.01) |

.02 (.01) |

−.01 (.01) |

.01* (.004) |

−.03 (.06) |

−.01 (.03) |

.02 (.11) |

.08 (.14) |

−.004 (.05) |

.02 (.04) |

.01 (.11) |

.06 (.13) |

| Tempo |

.01* (.002) |

−.004* (.001) |

−.02 (.25) |

.12 (.20) |

−.37 (.44) |

−1.36* (.70) |

−.05 (.21) |

−.31 (.25) |

−.35 (.39) |

−1.13 (.70) |

||

| Timing × Tempo | .21 (.32) |

−.07 (.25) |

−.67 (.62) |

.13 (.95) |

−.01 (.27) |

−.33 (.31) |

−.52 (.56) |

.34 (.92) |

||||

| Peer Problem Behavior Model |

.70* (.11) |

.25 (.24) |

||||||||||

| Peer Substance Use Model |

.80* (.17) |

.68* (.21) |

||||||||||

| PARENTAL SOLICITATION AS MODERATOR | ||||||||||||

| Predictor | Low PS | High PS | Low PS | High PS | Low PS | High PS | Low PS | High PS | Low PS | High PS | Low PS | High PS |

| Timing | .01 (.01) |

.01 (.01) |

.001 (.01) |

−.004 (.004) |

.02 (.05) |

−.06 (.05) |

−.04 (.10) |

.25* (.13) |

.04 (.04) |

−.03 (.04) |

−.05 (.10) |

.23 (.13) |

| Tempo |

.01* (.002) |

−.001 (.001) |

.07 (.21) |

.02 (.17) |

−.48 (.41) |

−1.84* (.65) |

−.05 (.18) |

−.26 (.27) |

−.40 (.38) |

−1.64* (.66) |

||

| Timing × Tempo | −.07 (.26) |

.34 (.23) |

−.39 (.56) |

−.54 (.65) |

−.19 (.24) |

.04 (.33) |

−.29 (.53) |

−.36 (.67) |

||||

| Peer Problem Behavior Model |

.62* (.15) |

.60* (.18) |

||||||||||

| Peer Substance Use Model |

.72* (.15) |

.76 * (.22) |

||||||||||

Note. Parameter estimates are from the full model, wherein means, variances, and path estimates were allowed to vary across high and low knowledge groups. Effects of covariates (age and cohort) are excluded here for ease of interpretation, but see Figures. This table summarizes four separate models (two with child disclosure as the moderator, top panel; and two with parental solicitation as the moderator, bottom panel). The two measures of peer deviance (problem behavior – middle two columns, and substance use – last two columns) were each included in separate models. Associations of measures of puberty were modeled as covariances and are identical in both models including the same moderator but different peer deviance measures, and thus is presented once for each measure of peer deviance. CD = child disclosure. PS = parental solicitation.

p < .05.

Underlined text indicates significant difference in parameter estimates between low and high groups. Unstandardized beta-weights are presented. Standard errors are presented in parentheses. The analytic sample was 391 for models including CD and 389 for models including PS. Timing and tempo were assessed from repeated measures across all waves (the mid-point of development occurring prior to W6). Peer deviance and parental knowledge measures were assessed at W6, and substance use was assessed at W7.

Girls

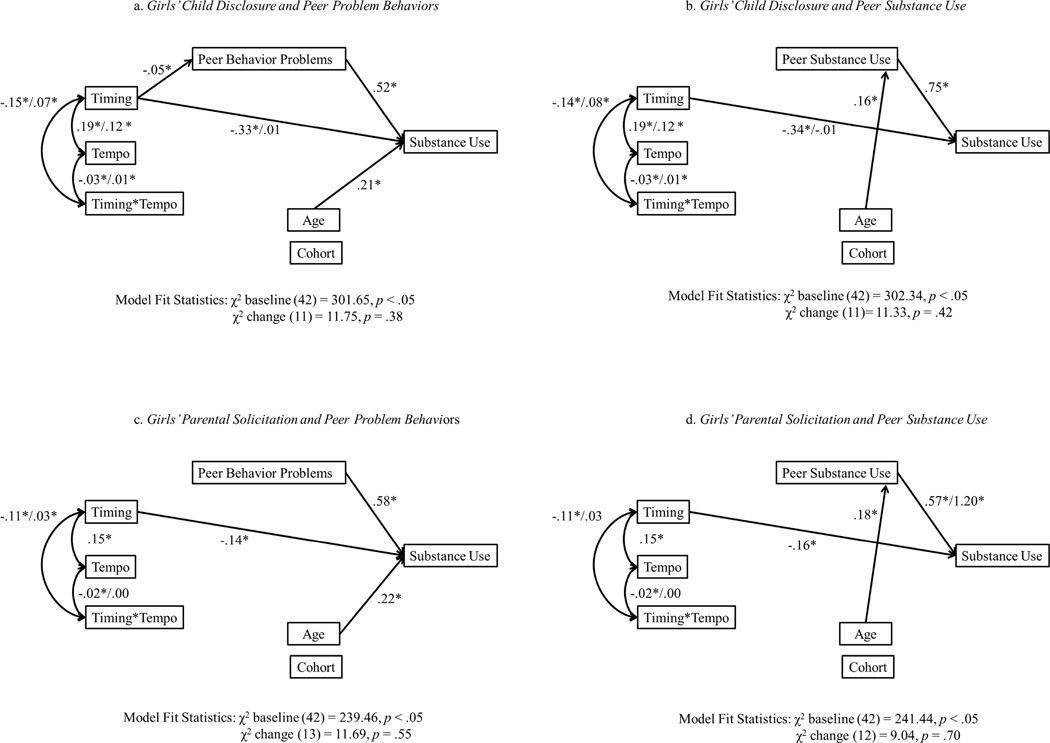

For girls, the association of pubertal timing and SU was moderated by child disclosure. Earlier timing was associated with higher likelihood of SU in girls who disclosed less, β=−.34, SE=.06, but not in girls who disclosed more, β=−.01, SE=.06 (Figure 2a, 2b; Table 3, top panel). However, earlier timing was associated with a higher likelihood of SU in girls equally in low and high parental solicitation groups (Figure 2c, 2d; Table 3, bottom panel). More peer problem behaviors (Figure 2a, 2c) were each associated with a higher likelihood of SU, equally in high and low child disclosure and parental solicitation groups. Peer SU was associated with a higher likelihood of SU equally in low and high disclosure groups (Figure 2b) but surprisingly was significantly stronger for girls who reported experiencing higher parental solicitation, β=1.0, SE=.11 than for girls who experienced lower solicitation, β=.69, SE=.11 (Figure 2d). Finally, in the model considering child disclosure as a moderator, earlier timing was associated with more peer problem behaviors which in turn were associated with a higher likelihood of SU (Figure 2a). This indirect effect was significant, β=−.03, SE=.01, p<.05, but was not moderated by child disclosure. Thus, results supported the hypothesized mediated effect in only one model.

Figure 2. Most Parsimonious Models for Girls.

Unstandardized parameter estimates from the best-fitting, most parsimonious model, wherein all paths that could be constrained to equality across high and low knowledge groups were constrained, are presented (hence, the parameter estimates may differ somewhat from the results for the full model presented in Tables). Only significant paths are depicted. Results from all four models for boys are presented: models including child disclosure as a moderator are presented in the top panel (2a, 2b), and models including parental solicitation as a moderator are presented in the bottom panel (2c, 2d). Models including peer behavior problems as the measure of peer deviance are presented on the left (2a, 2c) and models including peer substance use as the measure of peer deviance are presented on the right (2b, 2d). When paths show significant moderation, the low disclosure group is on the left of the / and the high disclosure group is on the right. * p < .05. Paths with a single estimate were constrained across groups without a decrement in model fit. Timing and tempo were assessed from repeated measures across all waves (the mid-point of development occurring prior to W6). Peer deviance and parental knowledge measures were assessed at W6, and substance use was assessed at W7.

Table 3.

Parameters for Models of Puberty, Parental Knowledge (Child Disclosure and Parental Solicitation), Peer Deviance (Problem Behaviors and Peer Substance Use), and Substance Use for Girls.

| Outcome | Puberty | Peer Problem Behavior Model | Peer Substance Use Model | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tempo | Timing × Tempo | Peer Problem Behavior |

Substance Use | Peer Deviance | Substance Use | |||||||

| CHILD DISCLOSURE AS A MODERATOR | ||||||||||||

| Predictor | Low CD |

High CD |

Low CD |

High CD |

Low CD |

High CD |

Low CD |

High CD |

Low CD |

High CD |

Low CD |

High CD |

| Timing |

.19* (.03) |

.12* (.02) |

−.15* (.02) |

.08* (.02) |

−.01 (.04) |

−.06* (.03) |

−.32* (.06) |

−.01 (.07) |

.02 (.04) |

−.02 (.03) |

−.33 (.06) |

−.03 (.06) |

| Tempo |

−.03* (.004) |

.01* (.002) |

.17 (.27) |

−.14 (.24) |

.23 (.42) |

.68* (.52) |

.22 (.25) |

−.19 (.27) |

.16 (.39) |

.76 (.50) |

||

| Timing × Tempo | −.11 (.14) |

.03 (.13) |

−.27 (.18) |

.06 (.32) |

−.07 (.13) |

.13 (.15) |

−.28 (.16) |

−.02 (.32) |

||||

| Peer Problem Behavior Model |

.59* (.10) |

.53* (.18) |

||||||||||

| Peer Substance Use Model |

.78* (.11) |

.78* (.13) |

||||||||||

| PARENTAL SOLICITATION AS A MODERATOR | ||||||||||||

| Predictor | Low PS | High PS | Low PS | High PS | Low PS | High PS | Low PS | High PS | Low PS | High PS | Low PS | High PS |

| Timing | .18* (.03) |

.14* (.02) |

−.12 (.02) |

.03 (.02) |

−.05 (.04) |

.00 (.03) |

−.19* (.07) |

−.08 (.07) |

−.01 (.04) |

.03 (.03) |

−.21* (.06) |

−.11 (.06) |

| Tempo |

.02* (.003) |

.00 (.002) |

.26 (.28) |

−.23 (.22) |

.32 (.45) |

.07 (.48) |

.10 (.27) |

−.02 (.21) |

.40 (.43) |

−.05 (.43) |

||

| Timing × Tempo | −.09 (.15) |

−.09 (.09) |

−.11 (.17) |

.18 (.29) |

−.05 (.12) |

−.03 (.14) |

−.12 (.17) |

.16 (.24) |

||||

| Peer Problem Behavior Model |

.56* (.10) |

.60* (.17) |

||||||||||

| Peer Substance Use Model |

.68* (.11) |

.90* (.12) |

||||||||||

Note. Parameter estimates are from the full model, wherein means, variances, and path estimates were allowed to vary across high and low knowledge groups. Effects of covariates (age and cohort) are excluded here for ease of interpretation, but see Figures. This table summarizes four separate models (two with child disclosure as the moderator, top panel; and two with parental solicitation as the moderator, bottom panel). The two measures of peer deviance (problem behavior – middle two columns, and substance use – last two columns) were each included in separate models. Associations of measures of puberty were modeled as covariances and are identical in both models including the same moderator but different peer deviance measures, and thus is presented once for each measure of peer deviance. CD = child disclosure. PS = parental solicitation.

p < .05.

Underlined text indicates significant difference in parameter estimates between low and high groups. Unstandardized beta-weights are presented. Standard errors are presented in parentheses. The analytic sample was 391 for models including CD and 389 for models including PS. Timing and tempo were assessed from repeated measures across all waves (the mid-point of development occurring prior to W6). Peer deviance and parental knowledge measures were assessed at W6, and substance use was assessed at W7.

Sensitivity Analyses

Results for sensitivity analyses examining each of the SU variables (sipping, consuming a full drink, heavy drinking, cigarette puffing, smoking a full cigarette, and marijuana use) separately are available upon author request. Generally, for boys, there was consistency in paths from peer behaviors for all substances, and consistency for the effects for tempo (except cigarette puffing) and timing. Moderation findings for child disclosure were also consistent, and moderation findings for parental solicitation differed only for marijuana use. For girls, again there was consistency in paths from peer behaviors, timing, and tempo for all substances. Parent solicitation was no longer a moderator for all substances, and there were some minor differences for child disclosure as a moderator (for consumption of a full drink, a new effect for tempo; for puffing, a new effect for timing by tempo and no longer a significant effect for timing, the indirect effect was only a trend for drinking variables).

Discussion

The present study built on research investigating the contextual processes underlying the association between pubertal risk and substance use outcomes. We sought to replicate and extend work by Westling et al., (2008), using a more nuanced assessment of both puberty and context (both peer and parent-related). Except in one case, we failed to detect an association between pubertal timing or tempo and peer deviance for boys or girls. Like Westling and colleagues, we detected a significant indirect effect such that greater W6 peer problem behavior (although not peer substance use) mediated the association between girls’ perceived early pubertal timing and substance use by W7. Contrary to hypotheses, we did not observe moderation of this effect by W6 parental knowledge. It is unclear why a more general measure of problem behavior was more instrumental than a specific measure of substance use, as prior work (focused on peer alcohol use) has supported mediated effects via peer substance use (13, 16, 31).

A significant mediated effect for peer problem behavior was evident for girls but not boys, which suggests that the mechanisms underlying pubertal timing and substance use seemingly differ for boys and girls. This finding contradicts prior work (16) showing no gender difference for weekly drinking, a more severe outcome than examined here. Our study was focused on early milestones in the progression of substance use; future research should examine these processes with subsequent milestones such as regular use, heavy use, and dependence. Our finding that for girls, perceived early pubertal timing was associated with a higher likelihood of substance use in mid-adolescence supports the developmental readiness hypothesis (9) and replicates prior findings by other researchers (8, 32) and our own work using a subset of this data (5). This association was particularly pronounced for youth reporting low parental knowledge, as indexed by both parental solicitation and child-driven knowledge, supporting a contextual amplification hypothesis whereby influential contexts may magnify the influence of pubertal maturation on adolescent problem behavior (33). In addition, in boys, slower perceived pubertal tempo was associated with greater substance use, consistent with some studies examining other behavior problems in adolescence (5–7).

Youth reporting greater peer substance use were more likely to endorse having used substances themselves; unexpectedly, this was particularly true for girls who reported greater parental solicitation of their whereabouts and activities, which contradicts prior work showing weaker peer influence effects on substance use in positive family environments (34). These findings add to the body of work showing that positive parental influence mitigates the link between deviant peer association and adolescent substance use (19). Concerned parents may seek to increase their knowledge in response to adolescent risk behavior, and by extension associating with substance-using friends, as in an evocative effects framework (35). In general, the degree to which parental monitoring buffers the detrimental influence of peer deviance on adolescent substance use is unclear, with mixed findings in the literature (19); future work may need to better resolve these contextual processes before this framework is integrated into questions about pubertal development and substance use.

Limitations

Because pubertal timing and tempo were assessed via self-reported data, findings may reflect perceptions and/or actual physiological mechanisms. We also relied on participant report of substance use, peer behavior, and parenting, which may have introduced some bias due to misperception (36, 37), although self-report measures of substance use can be valid in youth (38), particularly when using web-based data collection (39). Our measures of peer problem behavior and substance use were taken from W6 in order to preserve the temporal ordering between pubertal timing/tempo and substance use; however, future research may consider peer behavior in a more developmental framework (e.g., as a timevarying covariate). Future research also might consider peer behavior as an additional potential amplifying factor (moderator) for the pubertal timing effect (40, 41), rather than as a mediator. Our study sample was drawn from a regional set of middle schools and is thus not representative of the U.S. Additionally, the attrition of relatively more non-disclosing adolescents further limits generalization of findings and may restrict the range in the moderator and inhibit the likelihood of finding moderation.

Summary

The relations between pubertal risk profiles and parent and peer contexts for substance use is complex and dynamic. Although this study showed that peer context partially mediated associations of early pubertal timing and substance use in girls in one model (of four), our data generally failed to support hypotheses. The failure to replicate specific mechanistic findings (13) here may reflect differences in the samples, or real differences in how different aspects of parenting (e.g., disclosure vs. solicitation) and peer contexts (general behavior problems vs. substance use) act across puberty. We supported the role of parental knowledge as a contextual amplifier or pubertal risk, and the largely independent role of peers for adolescent substance use. Our findings have implications for the prevention of addiction: 1) pubertal risk is an important but understudied area that can help identify at-risk youth who would benefit from prevention efforts, and 2) girls identified as at-risk through their pubertal profiles would particularly benefit from intervention seeking specifically to increase communication with their parents –both in terms of self-disclosure and solicitation– of their whereabouts and activities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the many youths and their parents who willingly participated in iSAY, as well as the team of investigators. This manuscript was written with funding support through the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA016838 and K02 AA021761, Jackson). Manuscript preparation was also supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (T32 DA016184, K01 DA039288 Marceau).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no other interests to declare.

Implications and Contribution: Low parental knowledge contextually amplified pubertal risk for adolescent substance use; the role of peers was largely independent. Girls identified as at-risk through pubertal profiles may benefit from interventions that increase bi-directional communication of their whereabouts/activities with parents. Peer groups remain important regardless of youths’ pubertal profiles and parenting environment.

References

- 1.Susman E, Dorn L. Puberty: Its role in development. In: Lerner R, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 3. New York: Wiley; 2009. pp. 116–151. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JS, McCarty CA, Ahrens K, King KM, Vander Stoep A, McCauley EA. Pubertal Timing and Adolescent Substance Initiation. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2014;14(3):286–307. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cance JD, Ennett ST, Morgan-Lopez AA, Foshee VA, Talley AE. Perceived pubertal timing and recent substance use among adolescents: a longitudinal perspective. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2013;108(10):1845–1854. doi: 10.1111/add.12214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castellanos-Ryan N, Parent S, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE, Seguin JR. Pubertal development, personality, and substance use: a 10-year longitudinal study from childhood to adolescence. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2013;122(3):782–796. doi: 10.1037/a0033133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marceau K, Abar C, Jackson K. Parental Knowledge is a Contextual Amplifier of Associations of Pubertal Maturation and Substance Use. J Youth Adolescence. 2015;44(9):1720–1734. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0335-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis EM, Peck JD, Peck BM, Kaplan HB. Associations between early alcohol and tobacco use and prolonged time to puberty in boys. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2015;41(3):459–466. doi: 10.1111/cch.12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendle J, Ferrero J. Detrimental psychological outcomes associated with pubertal timing in adolescent boys. Developmental Review. 2012;32(1):49–66. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendle J, Turkheimer E, Emery RE. Detrimental psychological outcomes associated with early pubertal timing in adolescent girls. Developmental Review. 2007;27(2):151–171. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ge X, Natsuaki MN. In Search of Explanations for Early Pubertal Timing Effects on Developmental Psychopathology. Current Directions in Pscyhological Science. 2009;18(6):327–331. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendle J, Harden KP, Brooks-Gunn J, Graber JA. Development's tortoise and hare: Pubertal timing, pubertal tempo, and depressive symptoms in boys and girls. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(5):1341–1353. doi: 10.1037/a0020205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dees WL, Hiney JK, Srivastava VK. Alcohol alters hypothalamic glial-neuronal communications involved in the neuroendocrine control of puberty: In vivo and in vitro assessments. Alcohol. 2015;49(7):631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Windle M, Spear LP, Fuligni AJ, Angold A, Brown JD, Pine D, et al. Transitions Into Underage and Problem Drinking: Developmental Processes and Mechanisms Between 10 and 15 Years of Age. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Supplement 4):S273–S289. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westling E, Andrews JA, Hampson SE, Peterson M. Pubertal Timing and Substance Use: The Effects of Gender, Parental Monitoring and Deviant Peers. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42(6):555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haynie DL. Contexts of Risk? Explaining the Link between Girls' Pubertal Development and Their Delinquency Involvement. Social Forces. 2003;82(1):355–397. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stattin H, Klackenberg-Larsson I. The relationship between maternal attributes in the early life of the child and the child's future criminal behavior. Development and psychopathology. 1990;2:99–111. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schelleman-Offermans K, Knibbe RA, Kuntsche E. Are the effects of early pubertal timing on the initiation of weekly alcohol use mediated by peers and/or parents? A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49(7):1277–1285. doi: 10.1037/a0029880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Negriff S, Brensilver M, Trickett PK. Elucidating the mechanisms linking early pubertal timing, sexual activity, and substance use for maltreated versus nonmaltreated adolescents. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2015;56(6):625–631. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood MD, Read JP, Mitchell RE, Brand NH. Do parents still matter? Parent and peer influences on alcohol involvement among recent high school graduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(1):19. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marschall-Levesque S, Castellanos-Ryan N, Vitaro F, Seguin JR. Moderators of the association between peer and target adolescent substance use. Addictive behaviors. 2014;39(1):48–70. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simons-Morton BG, Farhat T. Recent findings on peer group influences on adolescent smoking. The journal of primary prevention. 2010;31(4):191–208. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0220-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson KM, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Abar CC. Prevalence and correlates of sipping alcohol in a prospective middle school sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29(3):766–778. doi: 10.1037/adb0000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peterson AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity and initial norms. J Youth Adolescence. 1988;17(2):117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marceau K, Ram N, Houts RM, Grimm KJ, Susman EJ. Individual differences in boys' and girls' timing and tempo of puberty: Modeling development with nonlinear growth models. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(5):1389–1409. doi: 10.1037/a0023838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beltz AM, Corley RP, Bricker JB, Wadsworth SJ, Berenbaum SA. Modeling pubertal timing and tempo and examining links to behavior problems. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50(12):2715–2726. doi: 10.1037/a0038096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerr M, Stattin Hk. What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(3):366–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Health NLSoA. Delinquency Scale. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zucker RA. Peer Behavior Profile. Michigan Longitudinal Study [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arthur MW, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Pollard JA. Student survey of risk and protective factors and prevalence of alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use. Social Development Research Group, University of Washington; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables: User'ss Guide. Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Negriff S, Trickett PK. Peer substance use as a mediator between early pubertal timing and adolescent substance use: Longitudinal associations and moderating effect of maltreatment. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2012;126(1):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skoog T, Stattin H. Why and Under What Contextual Conditions Do Early-Maturing Girls Develop Problem Behaviors? Child Development Perspectives. 2014;8(3):158–162. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ge X, Brody GH, Conger RD, Simons RL, Murry VM. Contextual amplification of pubertal transition effects on deviant peer affiliation and externalizing behavior among African American children. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(1):42–54. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nash SG, McQueen A, Bray JH. Pathways to adolescent alcohol use: Family environment, peer influence, and parental expectations. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sameroff A. Transactional Models in Early Social Relations. Human Development. 1975;18(1–2):65–79. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perkins HW. MISPERCEPTIONS OF PEER SUBSTANCE USE AMONG YOUTH ARE REAL. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2012;107(5):888–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reynolds EK, MacPherson L, Matusiewicz AK, Schreiber WM, Lejuez CW. Discrepancy Between Mother and Child Reports of Parental Knowledge and the Relation to Risk Behavior Engagement. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40(1):67–79. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.533406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Goldman MS. Self-reported drinking and alcohol-related problems among early adolescents: dimensionality and validity over 24 months. Journal of studies on alcohol. 1995;56(4):383–394. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent Sexual Behavior, Drug Use, and Violence: Increased Reporting with Computer Survey Technology. Science. 1998;280(5365):867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Costello EJ, Sung M, Worthman C, Angold A. Pubertal maturation and the development of alcohol use and abuse. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2007;88(Supplement 1(0)):S50–S59. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biehl MC, Natsuaki MN, Ge X. The Influence of Pubertal Timing on Alcohol Use and Heavy Drinking Trajectories. J Youth Adolescence. 2006;36(2):153–167. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.