Abstract

The anthropological study of human biology, health, and child development provides a model with potential to address the gap in population-wide mental health interventions. Four key concepts from human biology can inform public mental health interventions: life history theory and tradeoffs, redundancy and plurality of pathways, cascades and multiplier effects in biological systems, and proximate feedback systems. A public mental health intervention for former child soldiers in Nepal is used to illustrate the role of these concepts in intervention design and evaluation. Future directions and recommendations for applying human biology theory in pursuit of public mental health interventions are discussed.

BACKGROUND

The burden of disease attributable to mental illness is rising rapidly, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs): the global burden of disease attributable to depression rose 37% from the 15th to the 11th leading cause of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) from 1990 to 2010 (Murray et al., 2012). The future projected rise is greatest in LMICs. Mental and behavioral disorders not only carry independent mortality risk, they also contribute to increased mortality and morbidity for a host of other health problems: maternal and reproductive health, child development, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and recovery from infectious disease (Prince et al., 2007). Mental illness, especially during childhood and adolescence, predicts poorer outcomes for educational and economic success and increased engagement with legal and justice systems in adulthood (Copeland et al., 2009; Danese et al., 2009; Lynam et al., 2007; Moffitt et al., 2011).

Despite increasing attention to global mental health, there is a dearth of mental health promotion models that have demonstrable population-wide effects in LMICs. What public health interventions could reduce the global burden of mental illness? Psychiatric epidemiology provides many clues to potential targets for intervention and prevention. Some of the most robust evidence comes from childhood exposure to chronic stressors and traumatic events. From a prevention and mental health promotion perspective, promising work has been conducted examining the impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) on adult physical and mental health outcomes. Across cohorts in United States with birth periods ranging from the 1930s to 1970s, each unit increase in ACE associated with a unit increase in depressed affect, sexually transmitted diseases, and suicide (Dube et al., 2003). In other samples, ACE associated with increased depression (Chapman et al., 2004), suicide (Dube et al., 2001), ischemic heart disease (Dong et al., 2004), and poor reproductive health outcomes including independent associations with both adolescent pregnancy and fetal death (Hillis et al., 2004). Among persons with mental illness, ACE associate with greater likelihood of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), number of depressive episodes, and suicide attempts (Chapman et al., 2007). Overall, persons with high levels of ACE die 20 years earlier than persons without ACE (Brown et al., 2009). Similarly, psychiatric genetics literature has demonstrated that childhood adverse events strongly contribute to vulnerability to depression and PTSD (Gillespie et al., 2009; Lupien et al., 2009). While interaction with genetic polymorphisms contributes to differential degrees of vulnerability, childhood adverse events are consistently a dominant contributor to mental health problems across all populations studied (Kohrt, 2014).

These findings suggest that reducing exposure to adverse childhood experiences has dramatic potential for improving population-wide mental health outcomes. In Western high-income countries, there are a range of initiatives to reduce childhood exposure to chronic stressors and traumas (MacMillan et al., 2009). While targeted interventions exist for high-risk families and families with legal requirements for intervention based on a history of child abuse, public health models are also needed to have population-wide effect comparable to the advances in sanitation and hygiene that reduce exposure to infectious disease (O’Donnell et al., 2008). The work of psychologist Uri Bronfenbrenner (1977, 1979, 1994, 2005) is attuned to this later approach by placing child development with a social ecology ecosystem that incorporates the range of risk and protective factors including families, peers, schools, communities, nations, and broader economic, cultural, and political processes. Developmental psychologists have applied the ecological transactional model to reducing risk of child maltreatment (Belsky, 1980; Cicchetti and Lynch, 1993; Cicchetti et al., 2000). However, few interventions actually engage with multiple ecological levels. Most are limited to only domain such as school settings, parents, or primary care (Freisthler et al., 2006; Zielinski and Bradshaw, 2006). Interventions that do engage with multiple levels, such as “wrap-around services” are limited to children already identified with risk and do not include primary prevention services (Suter and Bruns, 2009). This is true for most interventions identified as being “ecological,” they do not actually engage with multiple ecological levels (Kohrt, 2013).

We argue that ecological population-wide approaches to reducing childhood exposure to chronic stressors and trauma is a potential public health intervention to promote mental health. While beneficial developmental conditions are not a panacea for all mental health problems, both longitudinal prospective studies and gene-by-environment studies suggest that reducing exposure to stress and trauma during development can have a dramatic impact on mental health across a range of conditions (Franklin et al., 2014). The conceptual framework of Bronfenbrenner and others provides a way of viewing the multiple factors that lead to risk for maltreatment. Their ecological approaches are well complimented by theoretical frameworks from the anthropological field of human biology. Conceptual frameworks such as life-history theory, trade-offs, system cascades, and proximal and distal feedback processes (Blackwell et al., 2010; Brewis, 2012; Decaro et al., 2010; Nyberg et al., 2012; Stormer, 2011; Wells, 2012; Worthman and Kuzara, 2005; Worthman, 2009) all have relevance to design of prevention and intervention programs to reduce childhood exposure to stressors and trauma as well support treatment for those already exposed. Human biology theory is useful at both a metaphorical level to conceptualize social-ecological systems, and human biology is important as it lays out mechanisms and pathways by which experience “gets under the skin” to move from stressful exposure to mental health problems and illness (Worthman, 2009; Worthman and Costello, 2009).

In this article, we use a prevention and intervention program with child soldiers in Nepal as an example of an ecological intervention that draws upon human biology theoretical concepts. In public health terms, this was a combined “primary prevention” and “secondary prevention” intervention. The primary prevention component was to prevent exposure of children to stressful and traumatic life events. The secondary prevention component was to reduce risk of mental health problems and reverse mental health problems among those already exposed. (In contrast, “tertiary prevention” in mental health interventions refers to symptom reduction without reversal of disease status.) First, we describe the context of child soldiers in Nepal. There are unique factors related to the nature of the conflict and culture in Nepal that are distinct from experiences of child soldiers in Africa, who represent the typical model used to frame child soldier experiences. Second, we describe the development and content of the intervention, which resulted in a community-based engagement program. Third, we describe how the intervention was informed and implemented with key human biology theoretical concepts in mind: life history theory and trade-offs; redundancy and plurality of pathways in ecological systems; cascades and multiplier effects in biological systems; and reliance upon proximal feedback systems. We conclude by recommending that these concepts be considered in pursuit of public mental health promotion interventions in the context of child development.

CONTEXT: CHILD SOLDIERS IN NEPAL

Nepal is a landlocked country north of India and south of the Tibetan autonomous region of China, with a population of approximately 28 million. In 1996, the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoists), CPN (M), presented demands to the government of Nepal to address economic and social injustices, abolish the monarchy, and establish a constituent assembly. When the government refused to address these demands, the CPN (M) began an agrarian revolution. Government security forces and Maoists killed over 17,000 people during the People’s War, which lasted 11 years; with the majority of deaths at the hands of the Royal Nepal Army and the government’s police force (INSEC, 2008). The war ended in November of 2006, when the CPN (M) signed a peace treaty with the government. During 2008 elections, the CPN (M) won a two-thirds majority but later abandoned their top government positions.

In the humanitarian field, child soldiers are referred to as “children associated with armed forces or armed groups” (CAAFAG). The 2007 Paris Principles define CAAFAG as, any person below 18 years of age who is or who has been recruited or used by an armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to children, boys, and girls used as fighters, cooks, porters, messengers, spies, or for sexual purposes. It does not only refer to a child who is taking or has taken a direct part in hostilities (UNICEF, 2007).

In the context of Nepal, humanitarian organizations, United Nations organizations, and international and local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) define “child” as anyone under 18 years of age. In Nepal, full adult franchise occurs at the age of 18 years (Government of Nepal, 2006; His Majesty’s Government, 2003). In the context of this article, we therefore refer to “child” and “child soldier” by these conventions. However, our ethnographic research in Nepal has revealed that conceptual “child” versus “adult” distinctions with regard to both Nepali language terms and social expectations are not age-bound but related to developmental milestones and maturity (Kohrt and Maharjan, 2009). This discrepancy between institutional (international and national organizations) definitions and cultural expectations is a shortcoming of intervention selection and implementation that introduces potential unintended consequences, which we have discussed elsewhere (Kohrt and Maharjan, 2009).

During the war, the CPN (M)’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the Royal Nepal Army conscripted children as soldiers, sentries, spies, cooks, and porters (Human Rights Watch, 2007; United Nations, 2006). Local groups estimate that at the conclusion of the war approximately 9,000 members—one-third of the PLA—comprised 14- to 18-year olds with 40% being girls (Human Rights Watch, 2007). An estimated 10% of the Royal Nepal Army during the conflict was below the age of 18 (Singh, 2004).

Among the sample of child soldiers we have studied, 11% had joined under age 10, 44% joined between age 11 and 13, and 45% joined between the ages of 14 of 16 (Kohrt et al., 2008a). In this same sample, 18% were associated for fewer than 3 months, 44% for 3 to 6 months, 16% for 7 to 12 months, and 23% for more than 1 year. Twenty-one percent were part of a military regiment, and 51% had direct combat exposure. At the time of the study, all child soldiers were under 18 years of age. Mean age of boy soldiers was 15.96 years (95% CI 15.57–16.34) and for girl soldiers it was 15.56 (95% CI 15.18–15.90).

While the war affected child psychosocial wellbeing, it is important to consider the broader historical processes that affect child wellbeing. Poverty and discrimination, for example, are major influences on child wellbeing that predate the conflict and continue to exist since its resolution. Nepal’s history represents a legacy of political, economic, and cultural processes that have marginalized large sectors of the population, who then became the backbone of the Maoist revolution. Two dominant forces of marginalization are gender-based and caste-based discrimination. At the conclusion of the war, Nepal’s Gender-related Development Index (GDI) score, a measure of equality between women and men, was 0.545, which was among the lowest in the world; the greatest levels of equality occur in Western HIC nations such as Canada which has a score of 0.959 (UNDP, 2009). Nepal’s population consists of more than 60 ethnic and caste groups. There is a long history of hegemonic dominance by the Hindu high castes (Bahun and Chhetri) of minority ethnic groups (Janajati, who are predominantly Buddhist and shamanist) and of those deemed low caste (Dalit).

Our research demonstrated that child soldiers in Nepal showed a higher burden of depression, PTSD, and functional impairment than civilian children who were not associated with armed groups at the conclusion of the war (Kohrt et al., 2008). In 2007, a few months after signing peace accords, 55% of child soldiers had PTSD compared with 20% of matched civilian children. While differences in war trauma exposure (i.e., the greater exposure among child soldiers compared with civilian children) explains some of the difference between child soldiers and civilian children, there was still a significant difference between the two groups even after controlling for war-related exposures (Kohrt et al., 2008).

Unlike other contexts where children are conscripted, in Nepal many of the child soldiers reported that they voluntarily joined the Maoist army, with a range of motivations such as escaping poverty, enacting revenge on government police and army who were seen as perpetrators of violence and abuses in local communities, and seeking adventure. Thus, joining the Maoists was initially seen as a positive move by children to improve their communities. These children were dissatisfied with conditions in their homes and communities, and thus many did not want to return home after the war. Child soldiers expressed the thought that leaving the Maoist Army and reintegrating home made them vulnerable to stigma and discrimination. Many of the child soldiers stated that the discrimination from family, friends, and other community members contributed substantially to psychological distress, and peer and family rejection was even more distressing than the war experiences (Kohrt et al., 2010d).

Another problem was recruitment into postwar armed groups. Signing of peace accords in 2006 did not end the exposure of children to violence. After the war ended, the Young Communist League (YCL) was formed, in part from former members of the People’s Liberation Army. The YCL has recruited both former child soldiers and civilian children. In the 2008 election, the YCL was involved in threatening communities with violence in order to promote votes for the CPN (M). In addition to YCL related violence, there are a number of other militant groups. More than 25 different armed groups are active in southern Nepal. Some are splinter groups from Maoist militias while others are Indian-affiliated groups. Minors under the age of 18 years old have been involved with all of the identified militant groups. Ultimately, as substantial structural, emotional, and physical violence existed preconflict for Nepali child soldiers, a major challenge of Nepali child soldiers was to develop adequate and appropriate supportive social relations where they had been weak or nonexistent before the war (Kohrt and Maharjan, 2009; Kohrt et al., 2010a).

This intervention occurred against the backdrop of limited mental health and psychosocial service infrastructure in Nepal. Currently in Nepal, there are only 20 registered NGOs specifically identified within the field of mental health and psychosocial support; this is out of 37,000 national registered NGOs (Upadhaya et al., in press). Upadhaya et al. have documented that before the People’s War, NGOs commonly supported government initiatives of delivering quality health services. However, during and after the Maoist conflict, they played increasingly important roles in directly providing health services to conflict prone areas and marginalized populations. Increased funding during the conflict period helped NGOs to develop and strengthen their work in the mental health field in Nepal. Since 2010, new initiatives supporting NGOs to integrate mental health into primary health care have been supported by the Department for International Development (DfID) of the United Kingdom, the European Union, and the Grand Challenges Canada program.

Nepal has fewer than one psychiatrist, psychologist, or psychiatric nurse per 100,000 people (WHO, 2011). Most are concentrated in urban areas. Nepal has an estimated 1.8 psychiatric beds in general hospitals per 100,000 people, and fewer than 2.8 admissions to mental hospitals per 100,000 people. As a reference, the United States has 14.4 psychiatric beds in general hospitals per 100,000 people and 256.9 admissions per 100,000 people, thus representing a 100-fold difference with Nepal.

During the period of the conflict and since, there has been a growing cadre of psychosocial counselors. These are individuals who have completed a 6-month training course that includes 400 h of classroom learning, 150 h of clinical supervision, 350 h of practice, and 10 h of personal therapy (Jordans et al., 2003). The curriculum is rooted in Western psychotherapy and has been adapted to culture-specific practice strategies (Jordans et al., 2007; Tol et al., 2005). Psychosocial counselors engage in services for conflict-affected populations including torture survivors, child soldiers and their families, victims of trafficking and gender-based violence, persons with HIV/AIDS, and refugees, as well as urban clients with a range of problems such as educational and employment stressors, bereavement, and substance use. Psychosocial counselors also worked with child and adult populations.

Intervention research and ethical conduct

The information presented below regarding intervention development and evaluation represents a combination of multiple studies and data sources related to work with children affected by the People’s War in Nepal. The Nepali NGO Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO) Nepal implemented the formative research with child soldiers and intervention development and implementation from 2006 to 2009 with follow-up studies in 2012. The study comprised a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods to understand the mental health and psychosocial consequences of children’s participation in armed groups. Data presented here include pre and postintervention levels of community support for child soldiers (n = 222 at 12-month follow-up) and comparison civilian children who had not been conscripted into armed groups (n = 234 at 12-month follow-up). Data were gathered by a Nepali research team employed by TPO-Nepal with a background in field research who received a month-long training on qualitative and quantitative data collection as well as on the ethics of research with vulnerable children. The research was approved by the institutional review board of Emory University, Atlanta, USA, and the Nepal Health Research Council, Kathmandu, Nepal [for additional details on methods see Kohrt et al., (2010a, 2010b, 2008a) and Morley and Kohrt (2013)].

Intervention development and content

TPO Nepal was contracted by UNICEF to develop a psychosocial intervention for child soldiers in Nepal. Based on the results of the qualitative and quantitative research described above, the goals of the intervention were twofold: first, address the mental health effects based on prior exposure to trauma and stressful events from before, during, or after association with armed groups, and second, reduce additional exposure to stress and trauma for all children in the community by minimizing exposure of returning child soldiers to discrimination and trauma and reducing incentives to associate with new militarized political factions and gangs that formed after the war.

A population-wide ecological approach was selected for two reasons. First, interventions that have targeted exclusively child soldiers have been reported to be stigmatizing in other context (Betancourt et al., 2013a). We found that during the research, child soldiers did not want to be seen as beneficiary of any services exclusively because of being a child soldier because that would lead to stigmatization and potential resentment for receiving services (Kohrt et al., 2010a). In addition, while mental health problems were greater among child soldiers compared with civilian children, there were also many civilian children who had mental health problems who would benefit from an intervention (Kohrt et al., 2008b). A second reason for an ecological approach was the need to minimize risk of exposure to additional stressors and traumas on a population-wide basis. We found that community-level factors such as caste discrimination, female education, and other aspects of human development significantly contributed to the mental health of all children in the community (Kohrt et al., 2010d). We wanted to assure that all children benefited from efforts to reduce risk of violence exposure through conscription or exposure to other stressors.

Initially, UNICEF had contracted TPO-Nepal to explore the potential use of traditional healing rituals as a form of collective, community intervention. In Sierra Leone and Uganda, traditional rituals have been documented as a pathway for former soldiers, especially girl soldiers, to re-enter society (Betancourt et al., 2013a). However, girl soldiers in Nepal refused to participate in rituals identified by the community as promoting acceptance; they explained that traditional rituals increase community acceptance but at the expense of individual freedoms of girls and women (Kohrt, 2015). They saw the ritual as symbolic submission to patriarchy (c.f. Bennett, 1983; Dyregrov et al., 2002) rather than a positive experience to reintegrate. The girls instead wanted to participate in school and secular activities such as clubs and drama teams. This demonstrates that while the community had identified pathways to reintegration that would reduce discrimination, for the girl soldiers this came at the cost of their desired identity as independent women. They stated that they would prefer to be mistreated as rebel girls than to be accepted as submissive women. Therefore, the intervention did not center on use of traditional rituals. Another option was to do a school-only intervention. This has advantages in terms of feasible implementation. However, it leaves out children not enrolled in school—which was a common problem for former child soldiers. In addition, our research with a classroom based intervention has shown limited effectiveness in a randomized controlled trial when compared with a waitlist condition (Jordans et al., 2010). Outcomes were limited to gendered effects on prosocial behavior and no improvement in depression or PTSD symptoms compared with the children in the waitlist.

In our research, we identified wide variation in the mental health and psychosocial outcomes of former child soldiers based on the type of community to which they returned (Kohrt et al., 2010b). A challenge for child soldiers was acceptance from families, schools, peer groups, ethnic/religious groups, political parties, and local NGOs. For this reason, child soldiers could not be viewed only as individuals, who would have the same integration program across the country, regardless of region. For example, child soldiers in communities with majority high-caste groups had much lower support than those in communities with mixed ethnic groups (Kohrt et al., 2010b; Tol et al., 2013). Child soldiers also returned to very different family situations. For example, one girl in Eastern Nepal returned to a family where multiple relatives had joined the Maoists. In an other community, a boy returned home to a family worried his return would put them in danger. Therefore, any intervention needed to treat former child soldiers in interaction with their community. Thus, the bulk of our intervention focused on improving the community experience for child soldiers and for children in general.

The goals of the intervention were as follows:

Raise awareness about children’s mental health including risk factors and protective factors for positive mental health. This comprised a range of issues including but not limited to war and conflict. Other issues were poverty, poor physical health, lack of education, and impact of gender- and caste-based discrimination. We wanted to raise awareness among the community broadly including parents, teachers, political leaders, religious leaders, health workers, and other key stakeholders.

The next goal was to promote inclusion and acceptance of children who were discriminated against in society. Discrimination based on exposure to armed conflict was one of the topics, but a range of other concepts was also included. Experience of traumatic events was often a reason for discrimination. Previously, we had found that trauma of any nature was often blamed on the victim, usually through attribution to poor karma (Kohrt and Hruschka, 2010). Therefore, persons who experienced trauma were often blamed and marginalized in society. Other forms of discrimination included caste-based discrimination, which was severe against children in some regions of the country, especially mid- and far-western development regions. In addition, gender-based discrimination appeared to be a major determinant of poor mental health outcomes (Kohrt and Worthman, 2009). Therefore, social inclusion was a key mechanism for improving mental health and reducing incentives to join armed groups.

At a more specific level, we wanted to provide care for children and families with specific needs. This element represented family and child-based psychosocial services typical of complex emergency responses.

In order to provide these activities, we needed a wide reach in the community. The endeavor required representatives who could engage with stakeholders including children, parents and other family members, teachers, religious leaders, political leaders, NGO workers, health workers, and others. The program was to be implemented by local partner NGOs in the areas where child soldiers were reintegrating. Therefore, we chose a delivery agent of “Community Psychosocial Workers” (CPSWs). In our conceptualization, CPSWs bridged the standard NGO workers, who typically received brief 2- to 3-day sensitization psychosocial trainings but who had limited service expertise, with more technical psychosocial counselors, who in Nepal are individuals who have completed a 6-month intensive counseling training with ongoing supervision and provide direct services (Jordans et al., 2003). CPSWs would function between these two poles. Therefore, we developed a 28-day curriculum to train NGO workers to fulfill the role of CPSWs (Kohrt et al., 2007, 2010c). We used a model of practice-learning in which CPSWs gained skills, applied them in the community, then discussed and refined their skills while learning new skills in ongoing trainings. In practice, this meant dividing the 28-day training curriculum over a 4-month period during which CPSWs received specific modules, conducted supervised implementation, and then returned for additional training. The 28-day training was divided in six modules. The full manual and related program documents are available from TPO-Nepal (www.tponepal.org).

Part 1—Orientation (7 days)—The orientation covered basics of psychosocial approaches and psychosocial needs of children, communication skills, communication barriers, conducting community sensitization programs, identifying children in need of targeted care, impact of armed conflict and association with armed groups on psychosocial wellbeing of children

Part 2—Follow-Up Observation, Consolidation, and Extension of Skills (3 days)—After a few weeks of implementing these skills, CPSWs were brought back for consolidation and refinement of the earlier skills. CPSWs described current challenges and brainstormed problem solving in groups. Additional skills included helping children with emotional difficulties and psychological first aid

Part 3—First Skills Development (6 days)—The first targeted skill development addressed the communities’ role for children with psychosocial problems including reintegrating children associated with armed groups. This included activities such as problem management, relaxation exercises, understanding the social fabric, resiliency, ecological resiliency, the psychosocial assessment and support framework, integrating ecological resiliency in a psychosocial program, and working with community groups. We also included handling emergencies such as children with suicidal and self-harm behavior.

Part 4—Second Skills Development (4 days)—The second skill development focused on targeted areas such as psychological trauma, substance abuse, and stress. The primary skills were recognition and referral, as well as psychoeducation. With only 28 days of training, it would not have been appropriate for CPSWs to directly provide counseling services or other specialized care. Instead, they were taught to recognize and refer these children to psychosocial counselors who provided services in the community. The CPSWs role was to engage with the community broadly, but not provide direct services.

Part 5—Third Skill Development (4 days)—The third skill development focused on supporting key groups providing services to children. This included health workers especially health workers providing care to girls. Reproductive health was often unaddressed among teenage girls who had a range of reproductive health concerns as a result of war experiences. The goal was in part to normalize addressing reproductive health for girls. In addition, care for teachers was also important as they often experienced stress through involvement with children associated with armed groups, including feeling unsafe with former child soldiers in the classroom.

Part 6—Child Led Indicators (4 days)—The final module was a technique, Child Led Indicators (CLI), to help children identify needs, design interventions, and evaluate interventions in the community. This was intended to help CPSWs work with children to design local intervention activities in their communities—thus being local in design and implementation.

Throughout this training process, CPSWs gained skills to conduct specific activities such as sensitization and awareness-raising workshops in the general community and targeted engagement with key stakeholders such as teachers, health workers, mothers and women’s groups, and community leaders. They also gained skills to provide basic support to groups who care for children and to identify and refer children in need of specific care and help to assure their follow-up. Ultimately, the CPSWs delivered the bulk of a community-support and transformation intervention, with specific targeted services available for children and families through specialized psychosocial counselors. The community interventions were conducted for a minimum of 1 year, and some were continuing to operate 5 years after the original trainings.

The intervention was delivered in 8 districts throughout Nepal, with activities conducted in rural areas throughout the districts. Activities were more focused on rural rather than urban areas because many child soldiers had been reintegrated into their home communities. There homes were more likely to be in rural areas because those were the regions where Maoists focused their recruitment. The geographic zones included plains immediately north of the Indian border, middle hills, and the Himalayan mountains. The diversity of settings reflected the diversity of regions in Nepal and the main areas from which Maoists recruited children. The activities also covered a range of development regions. Development regions are divided from east to west across the country and each development region includes southern plains, middle hills, and northern Himalayas.

HUMAN BIOLOGY FRAMEWORK FOR INTERVENTION DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION

Interventions are often selected and adapted based on two processes: (1) continuing with prior practices, i.e., continuing to do what an organization has historically done, and (2) implementing interventions previously evaluated in scientific trials. However, both of these have the potential pitfall of not being grounded in a conceptual framework to understand human development and human biology in a specific context. In contrast, Bronfenbrenner and others have recommended intervention development based on localized ecological transactional models (Belsky, 1980; Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Cicchetti et al., 2000). A refugee working group associated with Queen Mary University College similarly advanced the field by developing a conceptual framework for complex humanitarian emergencies (Psychosocial Working Group, 2003). This includes the three domains of social ecology, human development, culture and values, economic resources, environmental resources, and physical resources. The work of Gregory Bateson at the intersection of psychiatry and anthropology also contributed to a theoretical framework using ecology and cybernetics to consider how best to develop interventions for alcohol use disorders (Bateson, 1971, 1972).

Theory and conceptual models in anthropological studies of human biology also hold tremendous potential to inform intervention development, especially in areas such as mental health promotion during child development. We have selected four elements from human biology theory to frame the processes in the intervention program for children affected by armed conflict in Nepal. First, we begin with life history theory and the concept of trade-offs to understand the origins of vulnerability and to inform what practices have greater potential to benefit former child soldiers and other children in conflict-affected settings. Second, we draw upon the concept of redundancy and pathway plurality in biological systems and human development to highlight the need for interventions that have multiple targets throughout social ecological systems. Third, we show how cascades and multiplier effects, which are central in human biology and development, also have the potential to improve reach and impact of interventions. Fourth, we conclude with the need to have mechanisms to measure proximate, as well as ultimate, impacts of interventions. Traditional evaluation processes that either focus on outputs or end-effects limit identification of pathways. They also limit course correction and modification when implementing interventions. Ultimately, human biology theory has the potential both as metaphor and as mechanism to improve intervention design, implementation, and evaluation.

Tenet 1. Life history theory and trade-offs inform risk factors and intervention targets

Within anthropology, human biology is conceptualized in terms of survival, behavioral, and reproductive objectives across the lifetime. The focus on life course necessitates understanding biological processes, behaviors, and psychoneuroendronicological mechanisms that mediate between the two across the lifetime rather than only viewing them as cross-sectional mechanisms. Traditionally life history theory focused on biology from a reproductive fitness perspective examining restraints related to mortality, adult size, and reproductive maturity (Stearns, 2000). Increasingly, life history theory has been used to understand both population-differences and individual-differences in health and behavior (Brewis, 2012; Decaro et al., 2010; Flinn et al., 2009; Nyberg et al., 2012; Vitzthum et al., 2009; Worthman, 2002; Worthman and Brown, 2005). A specific advancement has been moving from standard epidemiological models of between-individual differences, to focusing on the person-environment interaction to understand health and behavior (Worthman and Kuzara, 2005; Worthman, 2009). These principles have been applied not only to reproductive health, chronic disease, and mental health, but also symbolic health with relation to social status and behavior (Panter-Brick et al., 2012).

In the field of human biology, the focus on prenatal and early development has shown how the fetal and infant environments have profound effects on health and behavior across the life cycle (Barker, 1990; Barker et al., 2002; Drake and Walker, 2004; McDade et al., 2001; Phillips, 2002; Worthman and Kuzara, 2005). In the context of limited resources, adaptation processes to optimized fetal and infant survival set the stage for reproductive behavior, chronic metabolic health problems, stress reactivity, and vulnerability to common mental disorders. These health problems in adulthood can be more clearly understood through diachronic interpretations of reactions to early stressors rather than synchronic interpretations of disease as a dysfunctional biological system.

Increasingly, mental health interventions are taking early developmental processes into account to promote child physical and mental health, as well as later development. A study examining treatment of perinatal depression among mothers in Pakistan demonstrated that a highly modified cognitive behavioral therapy entitled the Thinking Healthy Program presented in the form of a parenting intervention for mothers reduced reported infant diarrheal episodes and increased complete immunization and contraception use at 12 months (Rahman et al., 2008). Play frequency with the infant at 12 months was also greater in the intervention arm for both mothers and fathers. A systematic review with meta-analyses showed associations of maternal depression with both stunted and underweight children (Surkan et al., 2011). This has led to multiple replication studies of the Thinking Health Program including in Ethiopia, South Africa, India, and other LMICs to examine ways in which childhood adversity can be reduced by targeting maternal mental health.

The mental health and behavior of child soldiers can be more effectively conceptualized when taking life history into account including the sociocultural context in which conscription occurs. Just as there are biological trade-offs between early survival and later health, child soldiers decisions represent trade-offs between perceived benefits and risks with life history influencing how these risks and benefits are taken into account. One of the public misconceptions about child soldiers’ life histories is the assumption that children always are forced to join an armed group and that the return home after war is guaranteed to be a salutogenic experience. These expectations are based on popularized images mostly from African conflicts. Media images represent child soldiers being abducted by militant groups, given drugs, and being forced to commit violence against one’s family and community. Such cases have been documented especially in conflicts involving the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda and Charles Taylor’s boy soldiers in Liberia and Sierra Leone. However, these do not represent every child soldier’s experiences in Sub-Saharan African conflicts or around the world (Betancourt et al., 2013a; Wessells, 1997). Moreover, in both Sierra Leone and Uganda, there are significant problems with stigma and discrimination in families and communities after the return home (Annan et al., 2011, 2009; Annan and Brier, 2010; Betancourt et al., 2010a, 2010b, 2013b).

Popular representations of child soldiers can easily lead to interventions that may not have the intended benefit or may be potentially harmful. In contrast to the popular images, the majority of children in Nepal reported joining armed groups voluntarily. In Nepal, the People’s War was initially represented by Maoists as an agrarian revolution with objectives not dissimilar from the those presented by development organizations, e.g., greater inclusion of women and ethnic/caste marginalized groups in society (Hutt, 2004; Lawoti, 2003; Thapa and Sijapati, 2003, 2004). The Maoists advocated for greater national control of resources to benefit the Nepali people rather than foreign governments and corporations. The Maoist ideology led to many youth—especially girls, low castes, and non-Hindu ethnic groups—joining voluntarily. In 2007 among 258 former child soldiers interviewed, we found that 29% reported joining the Maoists entirely voluntarily, 50% reported joining in part based on their own volition and in part based on decisions of others, and the remaining 21% reported that they had no say in whether or not to join the Maoists. Thus, approximately 80% of child soldiers joined based at least in part on their own volition. Among the 258 child soldiers, 32% said they joined the Maoists because they felt the Hindu monarchy did not reflect their political interests, 28% were not satisfied with the conditions of village life, and 24% said they joined to improve the country (these options were not mutually exclusive).

Children’s experiences in their home communities and life history before association are crucial when considering intervention. For former child soldiers, returning home is not a panacea for the trauma of war. The qualitative research revealed that many child soldiers described their experiences returning home after the war as more distressing than their experiences during war. Many girl soldiers described positive experiences during association with the Maoists, especially practices related to gender equality, which contrasted starkly with patriarchy and gender discrimination in their homes and communities (Kohrt et al., 2010d). Some girl soldiers reported they had joined the Maoists voluntarily because their parents had forced them to stop their education while their male relatives could continue schooling because it was seen as more useful and appropriate for boys. When these girls returned home after the war, they were shunned by their families, teachers, and other members of the community. Interviews with adults revealed that former child soldiers, especially girl soldiers, were considered ritually “polluted” because they had violated Hindu religious norms through their associations with Maoists (Kohrt, 2015). This pollution included traveling in mixed-caste groups, going into the homes of persons from different castes, sharing food across caste groups, and touching dead bodies.

Girl soldiers were additionally polluted through assumptions that they were sexually active during their time with the Maoists. However, most girl soldiers reported that they felt safer after they joined the Maoists compared with being in their homes and communities where they were sexually victimized by family members, community members, and security forces. Forms of discrimination after child soldiers returned home included not being allowed to participate in community activities, not being allowed to go to school, and being forced into marriage against their will. Some child soldiers reported being forced to sleep outside and not being fed with other family members. Child soldiers who did return to school reported being forced to sit on the floor in the classroom and being mocked by teachers: “Hey little Maoist, where is your army now?”

Not all child soldiers reported high levels of discrimination in the home, school, and community. Some child soldiers said that their families were happy to have them back, and that they had returned to school. Overall, in the qualitative research, we found that discrimination among child soldiers was greatest in the middle hills of mid-western Nepal, and areas of far-western Nepal (Kohrt et al., 2010b). These were areas with the highest conflict mortality and the greatest number of years of exposure to the war. These areas had the highest percentage of persons identified as Hindu in the districts. In other parts of the country, with mixed communities of Buddhist and Hindu practitioners, there appeared to be less discrimination of former child soldiers.

For child soldiers, joining the People’s Army was a decision for self-improvement. We have described this process elsewhere as “unbalanced agency”—the concept of trying to develop more agency and control of one’s fate but in the context of greater risk to one’s wellbeing—even risking loss of life or limb (Kohrt et al., 2010d). This is where the concept of life history trade-offs is central. For former child soldiers, joining the People’s Army was a trade-off between risking one’s life through military association and living in conditions of poverty, oppression, sexual violence, and other community-based risks. Therefore, for our intervention, we needed to address the community-risk factors that were experienced by returning child soldiers, as well as the risk factors related to joining new militant groups. The goal was to create opportunities for former child soldiers and other children that would be viewed as having greater long-term benefits that associating with armed groups. This led to the focus on community inclusion because community and family exclusion before war was both a risk factor for military association and a risk factor for mental health problems on return.

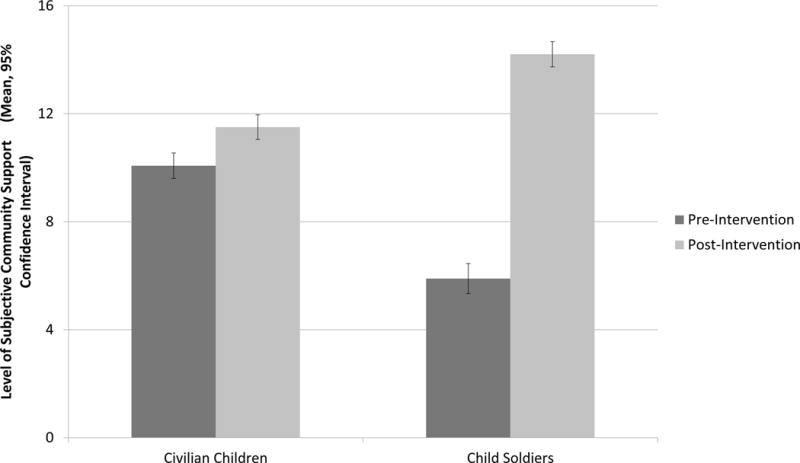

Ultimately, we implemented an intervention that improved supports by understanding the motivations of children in the context of other risk factors and life choices. The intervention described above accomplished this by focusing on mobilizing support from various sectors of the community. By the conclusion of year 1 of the program, former child soldiers felt significant improvement in community support. Figure 1 illustrates subjective community support reported by child soldiers compared with civilian children in 2007–2008 before the community intervention and 1 year later in 2008–2009 after 12 months of ongoing CPSW activities. It is important to consider what this intervention did not do. The intervention did not operate with the assumption that families and communities would be inherently supportive, and the intervention did not include a PTSD-specific individual treatment. Through an ecological and life history approach, the focus was shifted to the community and families. However, there are still long-term effects that continue to affect former child soldiers, especially girls. In 2012, we followed-up child soldiers 6 years after the People’s War ended. We found that former child soldiers are more likely to be married and have children than young adults of the same age who were not former child soldiers. We interpret this in relation to the lack of relationships available upon return and seeking out romantic relationships in order to have social ties and perceived support.

Figure 1.

Level of subjective community support reported by civilian children never associated with armed groups (N = 234) and child soldiers (N = 222). Preintervention levels were recorded in 2007–2008 before the Community Psychosocial Worker (CPSW) intervention, and postintervention levels were recorded in 2008 to 2009 after approximately 12 months of CPSW community activities. Subjective community support is the sum of family, peer, teacher, neighbor, and other community supports.

Tenet 2. Redundancy and plurality of pathways, which are characteristic of biological systems, are needed to optimize impact for population level interventions

A key aspect of human biology and development is redundancy and plurality of pathways (Ahn et al., 2006; Kitano, 2002; Tautz, 1992). Common ends can be achieved through multiple pathways. This is crucial because pathways can easily be perturbed by a range of competing demands. Growth, psychoneuroendocrine processes, neurosynaptic signaling, blood pressure, and myriad other systems have multiple signals and receptors throughout pathways in order to assure that biological goals are achieved. Increasingly, biological treatments for severe illnesses work by targeting multiple aspects of a pathway simultaneously, such as treatment of HIV and cancer. A shortcoming of many psychological interventions is restriction to one or two targets in social-ecological systems, such as only conducting an intervention at the individual level. More progressive interventions work by targeting multiple aspects such as the individual, his/her family, peers, and community (Freisthler et al., 2006; Zielinski and Bradshaw, 2006). This is especially important for children, for whom the developmental social ecology is key to health and wellbeing. This is also observable in child development—while critical periods and windows are present, they are not single time points, but cover multiple periods of opportunities (Maggi et al., 2010; Rice and Barone, 2000; Scovel, 2000).

Interventions with different targets can help to reduce deficits. This is also true, for example, about child attachment issues. Whereas mothers are most commonly the attachment figure, attachments can be formed with a range of individuals within and outside the family. Within high-risk settings, a healthy maternal attachment can be a strong source of resilience for physical and mental health. A common theme in resilience narratives for children at high risk with poor maternal attachment is having key attachment figures other than one’s mother. Wrap-around interventions achieve this, but are typically limited to only children with severe problems or disabilities and not as primary or secondary prevention (Freisthler et al., 2006; Zielinski and Bradshaw, 2006).

Similarly, a public mental health intervention for child soldiers requires that the intervention not rely upon a single individual. There are two reasons for this. First, the nature of migration and social instability in postconflict settings means that not all children may have the same resource person available. Some former child soldiers did not live with their parents after reintegration. Similarly, only relying upon teachers would be ineffective for those children who were not enrolled in school or who moved to a region where the school did not receive the psychosocial intervention. Second, if only one group were targeted, there may be public pressure not to participate in or implement the psychosocial intervention. For example, if only parents were targeted, teachers may deter parents from implementing services based on their misconceptions and prejudice. If only teachers or health workers were targeted, parents and peers may undermine the expected gains among these target groups. Therefore, because of the plurality of pathways, it was important to have CPSWs engage with as broad a range of stakeholders as possible.

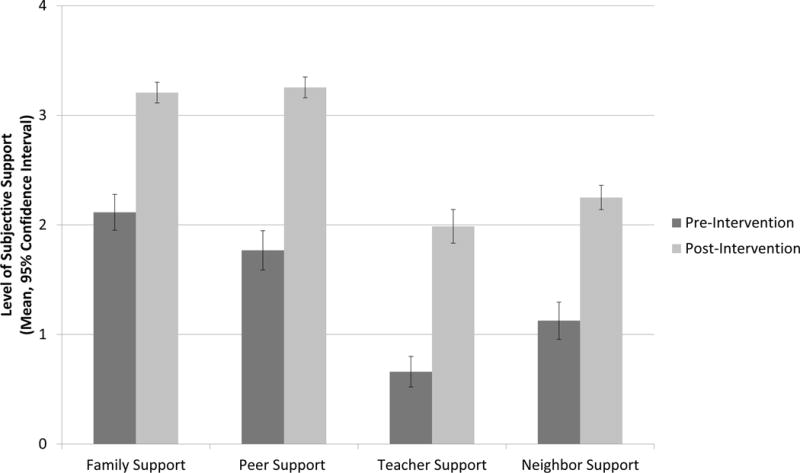

Therefore, the CPSWs were trained to focus on multiple key individuals in the community—as well as have flexibility in their implementation model to seek out other peer or adult stakeholders who may hold potential for positive child engagement in specific communities. This follows some tenets of wraparound services in which multiple individuals in the community are engaged in helping children. This way, if a child did not benefit from the CPSW outreach with parents, then the child could benefit from the outreach to teachers. Figure 2 illustrates the level of community support from different stakeholder groups before the intervention and 12 months.

Figure 2.

Level of subjective support reported by child soldiers (N = 222) pre and postintervention divided by community domain (family, peer, teacher, and neighbor). Preintervention levels were recorded in 2007 to 2008 before the Community Psychosocial Worker (CPSW) intervention, and postintervention levels were recorded in 2008 to 2009 after approximately 12 months of CPSW community activities.

Tenet 3. Cascades and multiplier effects increase the potential for sustained and population-wide health and behavior improvement

Challenges of existing intervention programs include how to encourage spread beyond direct beneficiaries and how to assure sustainability in the transition from research to real-life conditions (Madon et al., 2007; Tansella and Thornicroft, 2009; Thornicroft, 2012). A lesson from biological systems is the role of cascades and multiplier effects (Adiwijaya et al., 2006; Grubelnik et al., 2009). This is obvious in neuroendocrine pathways where limited and localized signaling in the CNS eventually spreads through hormone activity to most of the body’s systems (Sapolsky et al., 2000). The pathway from corticotrophin releasing hormone ultimately to cortisol’s effects throughout the body is exemplar of this process. When considering social ecology, social networks in general, and other social transactional systems, it is vital to attend to individual’s different types of social connections, relationship, and respective influences on behavior (Fowler and Christakis, 2010; Hruschka, 2010). The types of relationships for example, can have important impacts for eating behavior and substance use, leading to differential risk for obesity, infectious disease, and other health problems (Bastos and Strathdee, 2000; Beasley et al., 2010; Brewis et al., 2011; Edmonds et al., 2012; Garbarino and Sherman, 1980; Hruschka et al., 2011; Hruschka, 2012; Latkin and Knowlton, 2005; Thornicroft et al., 2005). Sensitivity to cascade effects and plurality of social pathways is increasingly prioritized in models of organizational and policy transformation (Fowler and Christakis, 2010; Grobman, 2005; Koehler, 2003).

We conceptualized the role of CPSWs with respect to cascades and multiplier effects in two ways: first, CPSWs were instructed to target as many potential stakeholders in child psychosocial wellbeing as possible. The sensitization and awareness raising programs were one technique to do this that could have broad reach in the communities. The second element was to target individuals who were most likely to induce cascade effects with regard to attitude and behavior change. A priori, we did not know who these individuals would be and how the social role of individuals who trigger cascade may differ across communities. However, through the iterative approach of having CPSWs participate in activities and attend follow-up trainings, we were able to work with them on identifying these persons. We found that in most communities, the cascade-trigger individuals were typically teachers. Teachers held positions of respect with regard to both changing parental and other adult behavior in the community and for changing student and peer behavior. When teachers became more invested in the psychosocial wellbeing of children including child soldiers, this appeared to have a cascade effect throughout the community. Similarly, the use of opinion leaders has been a central component of community wide behavior change for HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment (Anderson et al., 2006; Kloos et al., 2005; NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group, 2007).

The work with teachers in part related to increasing awareness about child psychosocial needs and teaching basic skills. However, a more important aspect was addressing the emotional wellbeing of teachers in the postconflict context. Just as we quickly learned that teachers were opinion leaders in the communities, the Maoists had also targeted teachers as opinion leaders. Maoist use coercion and in some cases violence and torture to get teachers to publicly support Maoist activities. A famous photo from the conflict is a teacher with his hand cut off so he could no longer write the monarchy’s version of a Hindu-privileged history of Nepal. Teachers were often thus very afraid of having former child soldiers in their classrooms.

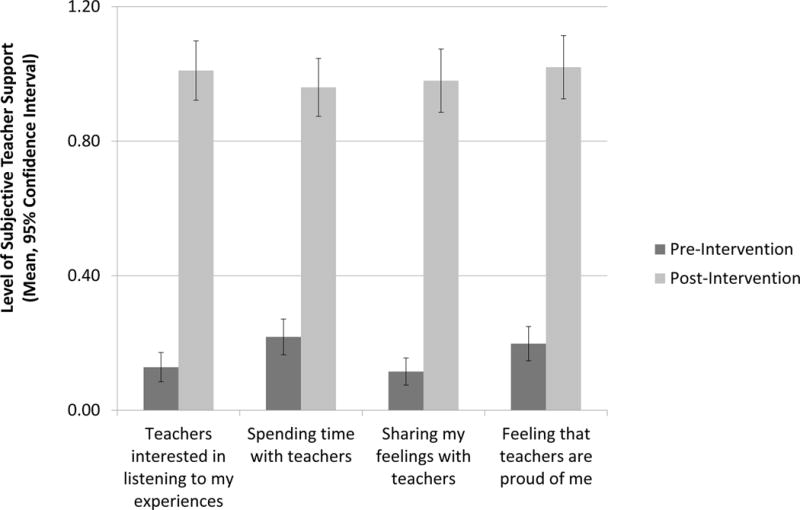

Not surprisingly, child soldiers in many communities identified teachers as a primary source of discrimination. Teachers often mocked them, calling them “little Maoists”; they did not let them sit in the classroom, or made them sit on the floor rather than on benches. Girls in the Maoists often cut their hair short. One teacher told a former girl soldier she could not return to school until her hair was long enough to be put into pigtails. The teachers modeled behavior that was then imitated by other students in the classroom. Similarly, the teachers’ behavior was also seen as acceptable by other adults in the community. When teachers often said that it was not worthwhile to send child soldiers back to school, parents echoed the same message to their children. Therefore, in our intervention, we gave special attention to teachers with the hopes that changing their behavior would lead to changed behavior among other students, parents, and others in the community. The CPSWs were trained to listen to teachers concerns and refer them for individual counseling if they had psychological trauma symptoms. In addition, CPSWs facilitated interactions between teachers and former child soldiers so that former child soldiers could communicate their commitment to returning to school. For many child soldiers, getting an education was their first priority during reintegration (Morley and Kohrt, 2013). In addition, UNICEF provided funding to local NGOs to give financial incentives to schools that accepted former child soldiers. Incentives were given to schools for infrastructure development and not to specific teachers. Gradually, through financial incentives, mental health support of teachers, facilitated interactions, and changes in the political climate, child soldiers reported that teachers became increasingly supportive. Figure 3 illustrates different behaviors among teachers toward child soldiers before and after 12 months of CPSW activities.

Figure 3.

Level of subjective support from teachers reported by child soldiers (N = 222) pre and postintervention. Preintervention levels were recorded in 2007 to 2008 before the Community Psychosocial Worker (CPSW) intervention, and postintervention levels were recorded in 2008 to 2009 after approximately 12 months of CPSW community activities.

Tenet 4. Feedback processes through measurement of proximate effects are crucial to illuminate mechanisms of change and for modifying interventions during implementation

The next piece that is emblematic of biological systems is the range of proximate and ultimate feedback pathways (Hester et al., 2011; Jeong et al., 2000; Pessoa and Adolphs, 2010; Tyson and Othmer, 1978). This is especially important because of multipliers, cascades, and redundancy. With multiple pathways at work to produce an effect, there also needs to be a range of processes to communicate when the change is being communicated so that it is not too strong or ongoing without moderation or cessation. In human biology, proximate feedback is crucial to regulation. From intracellular ultrashort feedback loops such as FKBP5 to feedback loops at synaptic signaling junctures, one of the keys of biological systems is measuring activity at each step in a pathway (Davies et al., 2002; Sapolsky et al., 2000). When feedback systems fail, this leads to problems in biological systems from endocrine disorders to cancer (Spiegel and Sephton, 2001). In a developmental mental health intervention, we also considered the need for multiple feedback systems to see what was working, what aspects of the system were not benefiting, and when effort was being allocated ineffectively. The central tenet of the feedback system is to have multiple different types of measurement in place across a range of sources and time scales. Gregory Bateson in his work on ecology and cybernetics also observed that the speed at which information moves through a system increases the frequency of change (Bateson, 1972). Therefore, if incremental markers of change are measured more frequently, this increases the potential for adaptation and course correction in interventions.

A limitation of most interventions in complex emergencies is reliance upon measuring “outputs” which refer to countable processes that may or may not be associated with impact. For example, the number of trainings, number of people trained, number of people at a sensitization workshop—these often form the main metrics for NGO activities. In randomized controlled trials where the impact of interventions is evaluated, this is often limited to ultimate outcomes of whether or not a health or behavioral condition has improved. However, intermediate factors are often not measured, or are only associated at the end of an intervention through sensitivity and moderator analyses. Another approach—one that is more pragmatic—is to measure proximate changes along a pathway and make alterations during the implementation of an intervention. This is increasingly part of incorporating theory of change models in interventions (Anderson, 2008; Hawe et al., 2009; Judge and Bauld, 2001).

One unique aspect of identifying proximate outcomes was to work with former child soldiers to have them identify what they considered to be key indicators of successful intervention and prevention programs. Based on a participatory approach, former child soldiers in Nepal conducted a Child Led Indicators activity and developed a measure of positive psychosocial wellbeing (Karki et al., 2009). The process comprised working with small groups of 8 to 10 former child soldiers in which the children engaged in an extended participatory activity. Over a 3-day period, a group of children would complete seven activities: first, they described feelings in the heart-mind, which is the organ of emotion and memory in Nepali ethnopsychology (Kohrt and Harper, 2008; Kohrt and Hruschka, 2010). Second, they ranked feelings according to those most impairing in their lives and selected the most impairing feelings as the focus for subsequent steps. Third, they highlighted the causes of these target feelings and the effect these feelings have on their lives and the lives of others. Fourth, they identified the ideal psychosocial well-being for children their age (i.e., resiliency-promoting factors). Fifth, they mapped resources in their communities that could be mobilized to help solve psychosocial problems and promote psychosocial well-being. Sixth, they selected interventions and activities needed to achieve ideal well-being and promote resilience. In the final step, they selected child-led indicators for children to evaluate interventions.

The nine items on the Child-Led Indicator tool developed by the children included (1) being hopeful about the future, (2) desire to help others, (3) feeling safe, (4) confidence in speaking with others, (5) treating everyone equally and not engaging in caste or ethnic discrimination, (6) concentration on studies, (7) feeling free of unnecessary fear or fear for no reason, and (8) desire to improve one’s country. In the 7th step, they came up with things to measure in the community that would be observable and indicate—to them—that the intervention was headed in the correct direction, for example, monitoring school attendance and grades, doing focus groups, having street discussions, and conducting radio call-in shows to discuss changes in the community.

This demonstrates the importance of considering social ecological levels in addition to individual characteristics when identifying risk and protective factors for childhood resilience. Of note, the type of community contributed significantly to psychosocial wellbeing among former child soldiers. Children returning to communities with high levels of female literacy had greater wellbeing, whereas children returning to communities dominated by upper caste elites had poorer wellbeing. These factors are in turn influenced by factors such as cultural beliefs and policies related to gender and caste equality. What is striking is that community level factors explained 13% of the total variance, which was 25% of the variance explained in the model (Tol et al., 2013). The strongest predictors were female literacy in the community and percentage of high caste persons in the community. While caste could not be changed, and female literacy would take time, the study shed light on potential proximate variables that could be changed instead such as reducing discrimination and increased opportunities for women and low caste persons. Bronfenbrenner through his research and advocacy was instrumental in establishing the Head Start program in the United States as an approach to reduce socioeconomic barriers to education, which often occurred along racial and ethnic lines. Similar policies and programs are needed to foster resilience in Nepal.

Proximate measurements should be collected at multiple levels including individual psychological statuses, individual biological processes, and community level variables. One of the shortcomings of most current ecological studies is that proximal variables across the ecological system are not measured (Kohrt, 2013). Five years after participating in the intervention, we found that levels of EBV antibodies (a general marker of stress) were no different between child soldiers and civilian children. It would have been preferable to measure this at earlier times throughout the intervention to determine when processes are changing. In addition, in our studies in Central and South Asia, we have demonstrated an association between hypocortisolism and disruptive behaviors, such as physical aggression (Hruschka et al., 2005; Kohrt et al., 2014). It would have also been useful to study aggression and HPA activity prior to, during, and after the intervention to evaluate findings related to aggression risk ratios between child soldiers and civilian children, and over time.

Interventions could also be improved by measuring at each step in order to understand both mechanisms and identify potential sites for modification. A good example of this is N = 1 single case studies in which outcome variables are measured at various points in a lead-up to an intervention, during, and after. This helps determine when changes occur and what the active ingredients in an intervention are (Jordans et al., 2013, 2012).

CONCLUSION

In order to have population-wide impact, interventions to promote mental health need to be grounded in theories of human development informed by anthropology and human biology. Interventions need to conceptualize ecological systems and person-context interactions rather than treating individual health differentials independent of environment. While the intervention described here is tailored to a specific cultural context and type of risk exposure, the four key tenets of human biology theory we have outlined here can be incorporated into intervention design across a range of context to reduce exposure to and sequelae of developmental stress and trauma.

First, life history theory and trade-offs need to be taken into account to understand behavior and biological risks in the context of the life course, as this can inform key intervention targets as well as potential intervention approaches that will be successful in light of cost-benefit tradeoffs. This principle can be applied to a range of adolescent behaviors such as risk taking including drug use and unprotected sex. Tradeoffs associated with social status and peer relations may create potential barriers to mitigate these high-risk behaviors; therefore, these tradeoffs need to be address in intervention design and implementation. Similarly, disruptive externalizing behaviors and internalizing behaviors among children and adolescents likely have tradeoffs that impact the ability to intervene and change practices.

Second, interventions targeting population health need to echo redundancy and plurality of pathways observable in biological systems. Sensitivity to redundancy and multiple pathways illuminates the scope of stakeholders to be incorporated in an intervention. For example, interventions to reduce childhood obesity require implementation in multiple settings including the home, schools, recreational settings, and with policy makers and corporations.

Third, to optimize the reach of population approaches to mental health promotion, cascades and multiplier effects should be incorporated into all activities as this increases the potential for sustainability and reach. Cultural sensitivity to social networks can highlight those individuals most likely to trigger cascades of positive behavior change throughout communities. We suspect that with regard to children and adolescents, teachers will play a key role in triggering cascades for health problems related to obesity and bullying. Teachers can help shape attitudes and behaviors in the classroom that can influence social behaviors at home and in the community among peers.

Fourth, relying only on measuring outputs (e.g., number of beneficiaries) or one-time post-intervention outcomes (e.g., comparing one pre-intervention value to a post-intervention value) tells us little about mechanisms of change and does not allow interventions to evolve and adapt during implementation. Therefore, incorporating proximate biological, psychological, and community level assessments holds greater potential for long-term positive change. Measurement of changes in stress hormones, metabolic processes, and cardiovascular function can be important to evaluate degree and duration of meaningful change in health based on ecological interventions. These tenets of human biology research can help illuminate pathways to population-wide promotion of psychological wellbeing.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the TPO-Nepal staff involved in the intervention and manual development including Nabin Lamichhane, Rajesh Jha, and Em Perera. In addition, the authors thank Rohit Karki, Wietse Tol, and Christine Bourey for their involvement in child soldier study research design.

Contributor Information

Brandon A. Kohrt, Department of Anthropology, Emory University, Atlanta, Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO), Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal

Mark J.D. Jordans, Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO), Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal, Center for Global Mental Health, King’s College London, United Kingdom, HealthNet TPO, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Suraj Koirala, Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO), Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Carol M. Worthman, Department of Anthropology, Emory University, Atlanta

References

- Adiwijaya BS, Barton PI, Tidor B. Biological network design strategies: discovery through dynamic optimization. Mol Biosyst. 2006;2:650–659. doi: 10.1039/b610090b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn AC, Tewari M, Poon C-S, Phillips RS. The limits of reductionism in medicine: could systems biology offer an alternative? PLoS Med. 2006;3:e208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ES, Wagstaff DA, Heckman TG, Winett RA, Roffman RA, Solomon LJ, Cargill V, Kelly JA, Sikkema KJ. Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model: testing direct and mediated treatment effects on condom use among women in low-income housing. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31:70–79. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3101_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R. New MRC guidance on evaluating complex interventions. BMJ. 2008;337:a1937. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annan J, Blattman C, Mazurana D, Carlson K. Civil war, reintegration, and gender in Northern Uganda. J Conflict Resolut. 2011;55:877–908. [Google Scholar]

- Annan J, Brier M. The risk of return: intimate partner violence in northern Uganda’s armed conflict. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annan J, Brier M, Aryemo F. From “rebel” to “returnee” daily life and reintegration for young soldiers in Northern Uganda. J Adolesc Res. 2009;24:639–667. [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJP. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. Br Med J. 1990;301:1111–1111. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6761.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJP, Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Osmond C. Fetal origins of adult disease: strength of effects and biological basis. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:1235–1239. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos FI, Strathdee SA. Evaluating effectiveness of syringe exchange programmes: current issues and future prospects. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:1771–1782. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateson G. The cybernetics of “self”: a theory of alcoholism. Psychiatry. 1971;34:1–18. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1971.11023653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateson G. Steps to an ecology of mind; collected essays in anthropology, psychiatry, evolution, and epistemology. San Francisco: Chandler Pub. Co.; 1972. p. xxviii.p. 545. [Google Scholar]

- Beasley JM, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, Hampton JM, Ceballos RM, Titus-Ernstoff L, Egan KM, Holmes MD. Social networks and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Cancer Survivorship Res Pract. 2010;4:372–380. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0139-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Child maltreatment: an ecological integration. Am J Psychol. 1980;35:320–335. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.35.4.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett L. Dangerous wives and sacred sisters: social and symbolic roles of high-caste women in Nepal. New York: Columbia University Press; 1983. p. 353. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Agnew-Blais J, Gilman SE, Williams DR, Ellis BH. Past horrors, present struggles: the role of stigma in the association between war experiences and psychosocial adjustment among former child soldiers in Sierra Leone. Soc Sci Med. 2010a;70:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Borisova I, Williams TP, Meyers-Ohki SE, Rubin-Smith JE, Annan J, Kohrt BA. Research Review: Psychosocial adjustment and mental health in former child soldiers - a systematic review of the literature and recommendations for future research. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013a;54:17–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02620.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Brennan RT, Rubin-Smith J, Fitzmaurice GM, Gilman SE. Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: a longitudinal study of risk, protective factors, and mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010b;49:606–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Newnham EA, McBain R, Brennan RT. Post-traumatic stress symptoms among former child soldiers in Sierra Leone: follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2013b;203:196–202. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.113514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell AD, Snodgrass JJ, Madimenos FC, Sugiyama LS. Life history, immune function, and intestinal helminths: trade-offs among immunoglobulin E, C-reactive protein, and growth in an Amazonian population. Am J Human Biol. 2010;22:836–848. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.21092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewis AA. Obesity and human biology: toward a global perspective. Am J Human Biol. 2012;24:258–260. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewis AA, Hruschka DJ, Wutich A. Vulnerability to fat-stigma in women’s everyday relationships. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human-development. Am Psychol. 1977;32:513–531. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological models of human development International Encyclopedia of Education. 2nd. Oxford: Elsevier; 1994. pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Making human beings human: bioecological perspectives on human development. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brown DW, Anda RF, Tiemeier H, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB, Giles WH. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. Am J Prevent Med. 2009;37:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DP, Dube SR, Anda RF. Adverse childhood events as risk factors for negative mental health outcomes. Psychiatr Ann. 2007;37:359. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord. 2004;82:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Lynch M. Toward an ecological/ transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: consequences for children’s development. Psychiatry. 1993;56:96–118. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL, Maughan A. An ecological-transactional model of child maltreatment. In: Sameroff AJ, Lewis M, Miller SM, editors. Handbook of developmental psychopathology. 2nd. New York: Kluwer Academic; 2000. pp. 689–722. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, Angold A. Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:764–772. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Polanczyk G, Pariante CM, Poulton R, Caspi A. Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease: depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:1135–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies TH, Ning Y-M, Sanchez ER. A new first step in activation of steroid receptors: hormone-induced switching of FKBP51 and FKBP52 immunophilins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4597–4600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decaro JA, Decaro E, Worthman CM. Sex differences in child nutritional and immunological status 5–9 years post contact in fringe highland Papua New Guinea. Am J Human Biol. 2010;22:657–666. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.21062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williams JE, Chapman DP, Anda RF. Insights into causal pathways for ischemic heart disease adverse childhood experiences study. Circulation. 2004;110:1761–1766. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143074.54995.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]