Abstract

The harm associated with lung cancer treatment include perioperative morbidity and mortality and therapy-induced toxicities in various organs, including the heart and lungs. Optimal treatment therefore entails a need for risk assessment to weigh the probabilities of benefits versus harm. Exercise testing offers an opportunity to evaluate a patient’s physical fitness/exercise capacity objectively. In lung cancer, it is most often used to risk-stratify patients undergoing evaluation for lung cancer resection. In recent years, its use outside this context has been described, including in nonsurgical candidates and lung cancer survivors. In this article we review the physiology of exercise testing and lung cancer. Then, we assess the utility of exercise testing in patients with lung cancer in four contexts (preoperative evaluation for lung cancer resection, after lung cancer resection, lung cancer prognosis, and assessment of efficiency of exercise training programs) after systematically identifying original studies involving the most common forms of exercise tests in this patient population: laboratory cardiopulmonary exercise testing and simple field testing with the 6-minute walk test, shuttle walk test, and/or stair-climbing test. Lastly, we propose a conceptual framework for risk assessment of patients with lung cancer who are being considered for therapy and identify areas for further studies in this patient population.

Keywords: Exercise testing, Cardiopulmonary exercise testing, Six-minute walk test, Stair-climbing test, Shuttle walk test, Lung cancer

Introduction

“First, do no harm” is a key principle of clinical practice and medical ethics. Though a simple statement, the decision for optimal treatment can be very difficult in many situations in medicine, especially when dealing with diseases with a poor prognosis such as lung cancer. Such treatment decisions entail a need for risk assessment to weigh the probabilities of benefits versus harm.

Lung cancer treatment consists of a combination of modalities involving surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy, and/or immunotherapy. The associated immediate harm includes perioperative surgical complications and therapy-induced toxicities on various organs, including the heart and lungs. Perioperative morbidity/mortality depend on multiple factors, including patient-related factors (e.g., cardiopulmonary reserve, comorbidities), extent of the operation/surgical approach, and surgical/institutional expertise.1 Surgical mortality rates for lobectomy range from 1% to 5%.2 After lung resection, patients are at risk for impaired exercise capacity and persistent dyspnea and fatigue from the loss of lung function. Platinum-based chemotherapy, a mainstay treatment for advanced-stage lung cancer, is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease.3 Radiotherapy, with or without chemotherapy, can lead to cardiac dysfunction in patients with lung cancer who are undergoing treatment.4 Radiation pneumonitis will develop in 5% to 15% of those undergoing definitive external beam radiation therapy, with progressive pulmonary fibrosis, cor pulmonale, and/or respiratory failure subsequently developing in a minority.5 Cardiopulmonary toxicities of small molecule kinase inhibitors include interstitial lung disease (e.g., interstitial pneumonitis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis), pleural effusions, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and/or heart failure.5–11 Programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibition can lead to pneumonitis and worsening fatigue/dyspnea.12–14

To balance the benefits of lung cancer treatment against the associated harm,15 traditional risk assessment involves evaluation of the patient’s performance status, which has been shown to be an independent predictor of survival in patients receiving chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy.16 These scoring systems, however, are patient reported, rely on subjective factors, and often do not correlate well with patients’ perceptions of functional status; therefore, they are prone to inconsistencies.17

Exercise testing provides an opportunity to evaluate a patient’s functional status/exercise capacity objectively. In lung cancer, exercise testing is most often used in the preoperative physiologic assessment to risk-stratify patients for lung resection. An individual’s exercise capacity has been associated with the perioperative risk for morbidity and mortality. The role of exercise testing in patients with advanced lung cancer (i.e., nonsurgical candidates) and lung cancer survivors has also recently been explored.

Physiology of Exercise Testing and Lung Cancer

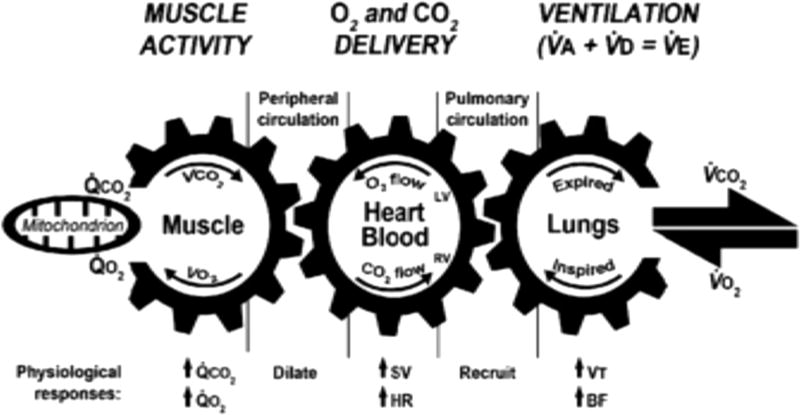

In exercising individuals, physiologic responses to meet the metabolic demands of contracting skeletal muscles involve changes in ventilation, cardiac output, and pulmonary and systemic blood flow to ultimately preserve cellular oxygenation and acid-base homeostasis.18 Assessment of exercise capacity traditionally relies on measurement of oxygen consumption ( , expressed in liters per minute or milliliters per kilogram per minute), reflecting one’s ability to take in, transport, and use oxygen to produce adenosine triphosphate during exercise (Fig. 1). In healthy individuals, maximum exercise tolerance is limited by the oxidative ability of skeletal muscle and/or cardiac output. With increasing exercise intensity, increases and reaches a point at which increasing exercise intensity no longer leads to an increase in (maximal [ ]). A normal usually excludes significant pulmonary, cardiovascular, hematologic, neuropsychological, and skeletal muscle disease.20 , therefore, is often regarded as the accepted standard measurement of cardiopulmonary fitness.18

Figure 1.

Diagram of cardiopulmonary exercise testing. BF, breathing frequency; CO2, carbon dioxide; HR, heart rate; LV, left ventricle; O2, oxygen; , elimination rate for carbon dioxide; , consumption rate for oxygen; RV, right ventricle; SV, stroke volume; , alveolar ventilation; , dead space ventilation; , minute ventilation; , carbon dioxide elimination; ,oxygen consumption; VT, tidal volume. Reprinted from Wasserman et al.19 with permission.

In patients with lung cancer, exercise limitations can be due to the effects of the cancer, coexisting morbidities, and/or the effects of treatment. Cancer-related anemia21 and muscle atrophy and dysfunction22 can limit oxygen content and oxygen utilization. Limitations of ventilation and gas exchange can be prominent in those with coexisting lung disease, whereas chronotropic incompetence and ventricular dysfunction due to ischemia and/or remodeling can limit cardiac output in patients with coexisting heart disease. Lung cancer treatment can lead to impairments in pulmonary and/or cardiovascular function. In time, the inactivity that accompanies cancer, its comorbidities, and treatment-related effects can reduce muscle strength and conditioning, further reducing exercise capacity.

Methods of Exercise Testing

Traditionally, is measured during formal cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET). In this test, patients are instructed to exercise using a treadmill or cycle ergometer at incrementally increasing workloads. is reached when there is a plateau of the measured with increasing workload. In individuals who do not reach , usually on account of prohibitive symptoms including those due to cardiac and/or pulmonary limitations, the term is used to describe the highest reached during CPET. Reference values have been proposed, adjusting to age, sex, and weight and height.20 Other methods of exercise testing include simple field tests, including the 6-minute walk test (6MWT), shuttle walk test (SWT), and stair-climbing test (SCT). Simple field tests can be self-paced or externally paced, ending after specific amounts of time, a designated distance or height, or development of prohibitive symptoms or volitional exhaustion. Their testing measurements, relative intensities, complexities, and relationships to and other clinical assessments/outcomes are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Common Exercise Tests

| Exercise Test |

Pacing | End Point | Principal Measurement |

Adjunct Measurements |

Intensity | Complexity | Relationship to | Relationship to PA | Relationship to PRO | Relationship to Clinical Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPET20 | Externally paced | Prohibitive symptoms or plateau of |

|

, VE, AT, HR, BP, O2 saturation, work | +++ | +++ | – | – | – | – | |

| 6MWT23,24 | Self-paced | 6-min duration | Distance | HR, BP, O2 saturation, desaturation indices, work | ++ | + | Moderate-strong | Moderate-strong | Weak-moderate | Consistently strong | |

| ESWT23,24 | Externally paced | Prohibitive symptoms or 20-min duration | Time | HR, O2 saturation, distance | ++ | ++ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| ISWT23,24 | Externally paced | Prohibitive symptoms or 12 total stages | Distance | HR, O2 saturation, VE | ++ | ++ | Strong | Weak-moderate | N/A | Suggestive | |

| SCT | Self-paced | Volitional exhaustion or designated height/flights of stairs | Height | HR, O2 saturation, time | ++ | + | Moderate-strong | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Note: In general, not specific to lung cancer.

6MWT, 6-minute walk test; AT, anaerobic threshold; BP, blood pressure; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise testing; ESWT, endurance shuttle walk test; ISWT, incremental shuttle walk test; HR, heart rate; O2, oxygen; PA, physical activity; PRO, patient-reported outcome; SCT, stair-climbing test; VE, minute ventilation; , oxygen consumption; min, minute.

In this manuscript, we review the current status of exercise testing in patients with lung cancer, provide a conceptual framework regarding the utility of exercise testing in this patient population, and explore knowledge gaps to guide future research efforts.

Methods

We used PubMed searches to identify studies by using the medical subject heading (MeSH) terms exercise testing and lung neoplasm and the keywords exercise testing or exercise test or the individual test (6-minute walk test, shuttle walk test, stair-climbing test, or cardiopulmonary exercise test) and lung cancer or the MeSH term lung neoplasm. Only original studies published in the English language were included. We then reviewed abstracts and/or articles for the type of exercise testing and the context in which they were used. We pre-formulated a framework for evaluating the utility of exercise testing in four different contexts: (1) preoperative evaluation of lung resection candidates, (2) follow-up after treatment, (3) prognosis, and (4) as an assessment tool for exercise-based interventions. In each context (Supplementary Digital Content E-Table 1), we summarized studies with the largest number of enrolled/included patients; in context 3 and 4 studies were grouped according to clinical stage and, in context 4, favoring randomized trials.

Results

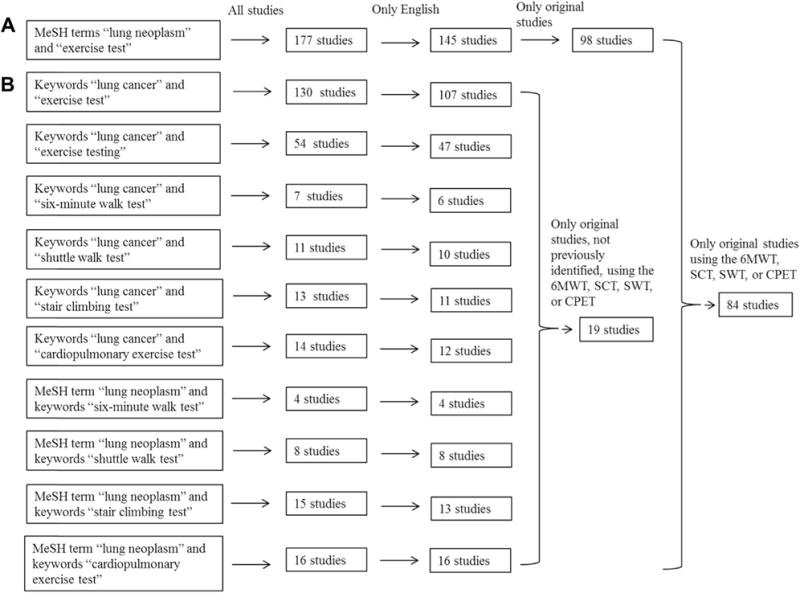

By using the MeSH search terms exercise testing and lung neoplasms, we found 98 studies involving the use of exercise testing in patients with lung cancer (Fig. 2A). The four exercise tests most frequently identified were as follows: (1) CPET (51 studies [52%]); (2) 6MWT (16 studies [16%]); (3) SCT (11 studies [11%]); and (4) SWT (four studies [4%]). Other forms of exercise testing/assessments included pedometers,25 stair steppers,26 the 12-minute walk test (12MWT),27 pulmonary hemodynamics/arterial occlusion,28–30 and bronchoscopic lobar occlusion during exercise.31 Additional PUBMED searches that used a combination of the aforementioned keywords and MeSH terms, including only articles not previously identified utilizing the four most common exercise tests resulted in19 additional studies. In total, 84 original studies in the English language involved CPET, 6MWT, SCT, and/or SWT in the population of patients with lung cancer (Table 2, Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of search results. (A) Initial search of studies involving all forms of exercise testing in lung cancer. (B) Identification of studies involving the four most common exercise tests in lung cancer. 6MWT, 6-minute walk test; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise testing; MeSH, medical subject headings; SCT, stair-climbing test; SWT, shuttle walk test.

Table 2.

Studies of Exercise Testing in Lung Cancer

| Exercise Test |

Preoperative Evaluation |

Posttreatment | Prognosis | Efficacy Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPET | 35 | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| 6MWT | 6 | 5 | 4 | 8 |

| ESWT | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ISWT | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SCT | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Totala | 42 | 15 | 13 | 15 |

Some studies used more than one exercise test.

6MWT, 6-minute walk test; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise testing; ESWT, endurance shuttle walk test; ISWT, incremental shuttle walk test; SCT, stair-climbing test.

Preoperative Evaluation for Lung Cancer Resection

In this context, the most common exercise tests were the SCT, SWT, and CPET, which measure the height climbed, distance walked, and respectively. Performance using these physiologic measurements correlates with perioperative morbidity and mortality; these assessments were therefore used to risk-stratify patients. The indications, cutoffs, and applications in clinical decision making are summarized for the most frequently used practice guidelines in Table 3.32–34

Table 3.

Summary of Guidelines for Exercise Testing in the Preoperative Evaluation for Lung Cancer Resection Surgery

| Clinical Question | ACCP Guideline32 | BTS Guideline34 | ERS/ESTS Guideline33 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whom to test/which test | ppoFEV1 or ppoDLCO

30%–60% SCT or SWT ppoFEV1 or ppoDLCO < 30%: CPET |

ppoFEV1 or ppoDLCO ≤ 40%: SWT or CPET | FEV1 or DLCO <

80% predicted: CPET |

| Functional cutoff indicating elevated risk | SCT height < 22 m, or SWT distance < 400 m, and/or < 20 mL/kg/min (75% predicted) |

SWT distance < 400 m, or < 15 mL/kg/min |

< 20 mL/kg/min (75% predicted) |

| Anatomic resection generally not recommended (i.e., “prohibitive risk”) | < 10 mL/kg/min (35% predicted) | SWT distance < 400 m, or < 15 mL/kg/min |

< 10 mL/kg/min (35% predicted) |

ACCP, American College of Chest Physicians; BTS, British Thoracic Society; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise testing; DLCO, diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; ERS/ESTS, European Respiratory Society/European Society of Thoracic Surgery; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; ppo, predicted postoperative; SCT, stair-climbing test; SWT, shuttle walk test; , peak oxygen consumption.

Since the most recent published guideline in 2013, we have identified five studies involving exercise testing in the preoperative evaluation of patients with lung cancer: two used CPET (to predict postoperative complications),35,36 two used the 6MWT,37,38 and one assessed the relationship between performance on the 6MWT, endurance shuttle walking test, and incremental shuttle walking test (ISWT) with CPET .39 Given the extensive review on the utility of CPET, SCT, and SWT in the previous practice guidelines and practical considerations in preoperative physiologic assessment, we sought to further evaluate the role of the 6MWT in the preoperative evaluation of patients with lung cancer.

6MWT

The first two studies involving walking tests utilized the 12MWT; both reported a lack of association between the 12MWT distance and postoperative (pulmonary27 or cardiopulmonary40) complications. In contrast, in two later studies using the 6MWT, the 6-minute walking distance (6MWD) was reported to be associated with respiratory failure41 and a 6MWD greater than 1000 feet (~ 300m) was predictive of survival at 90 days after surgery.42 On the basis of these four studies (Table 4), the European Respiratory Society/European Society of Thoracic Surgeons recommended against using the 6MWT in the preoperative assessment,33 a recommendation that has been cited and supported by the American College of Chest Physicians32; the British Thoracic Society did not give a specific recommendation regarding the 6MWT in this context.34 We identified two additional studies involving the 6MWT in the context of preoperative evaluation: Nakagawa et al.38 described significant correlations between and the 6MWD and oxygen desaturation, whereas Marjanski et al.37 described an association between a 6MWD less than 500 m with postoperative complications (Table 4).

Table 4.

Studies Involving the 12MWT/6MWT in the Preoperative Evaluation for Lung Cancer Resection Surgery

| Study | Study Design | Patient Selection | Walk Test Predictor | Outcomes Measured | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bagg et al.27 | Prospective cohort | 30 consecutive patients undergoing surgical evaluation; 22 underwent surgical resection | 12MWD | Respiratory complications | 12MWD did not differ between those with (n = 7) and without (n = 15) respiratory complications (mean 12MWD 968 ± 40 m vs. 930 ± 37 m, respectively) | |

| Markos et al.40 | Prospective cohort | 55 consecutive patients undergoing surgical evaluation, > 60 mm Hg, < 45 mm Hg while breathing ambient air; 47 underwent surgical resection | 12MWD | Cardiopulmonary complications (including 3 deaths) | 12MWD was not predictive of postoperative

complications Mean 12MWD = 1018 feet (~310 m) in those without complications (n = 32) vs. 905 ft (~276 m) in those with complications (n = 15) |

|

| Holden et al.42 | Prospective cohort | 23 consecutive high-risk patients (FEV1 < 1.6 liters) undergoing surgical evaluation; 19 patients underwent surgical resection | 6MWD | Death (5 patients died within 90 d of surgery) | 6MWD > 1000 feet (~300 m) was

predictive of a successful surgical outcome (survival 90 d after

surgery) Mean 6MWD 1315 feet (~401 m) in those with minor or no complications (n = 11) and 878 feet (~268 m) in those dying within 90 d after surgery (n = 5) (p < 0.05) |

|

| Pierce et al.41 | Prospective cohort | 54 consecutive patients, FEV1 > 55% predicted for pneumonectomy, 40% predicted for lobectomy, or ppoFEV1 > 30% predicted, and > 15 mL/kg/min; 52 underwent surgical resection | 6MWD | Postoperative complications (including 9 deaths within 32 d of surgery) | 6MWD, as a continuous variable, was predictive

of respiratory failure in MVA Mean 6MWD was 501 ± 47 m in those with postoperative complications (n = 36) vs. 556 ± 88 m in those without complications (n = 9) (p = 0.034) |

|

| Nakagawa et al.38 | Retrospective analysis | 51 patients with lung cancer who underwent both the 6MWT and CPET before surgery | 6MWD, O2 desaturation |

|

Significant correlation between and the 6MWD (r = 0.55, p < 0.001) and

O2 desaturation (>4%) (r = 0.538,

p < 0.001) 6MWD and O2 desaturation had AUCs of 0.692 (p = 0.02) and 0.814 (p < 0.001), respectively, when used to predict a < 15 mL/kg/min |

|

| Marjanski et al.37 | Retrospective analysis | 253 patients with lung cancer who underwent lobectomy and had 6MWT performed on the day before surgery | 6MWD | Postoperative complications | 6MWD < 500 m was associated with

postoperative complications; OR = 2.63 (1.42–4.88, p

= 0.001) 6MWD < 500 m had an AUC of 0.593 (CI: 0.530–0.654) when used to predict high vs. low complication rates |

6MWD, 6-minute walk distance; 6MWT, 6-minute walk test; 12MWD, twelve-minute walk distance; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; MVA, multivariable analysis; O2, oxygen; OR, odds ratio; , partial arterial pressure of carbon dioxide; , partial arterial pressure of oxygen; ppo, predictive postoperative; , oxygen consumption; d, day.

To understand the role of the 6MWT in the preoperative evaluation of candidates for lung cancer resection, further study is needed. The literature cited in the practice guidelines describes a lack of correlation between the 12-minute walking test distance and postoperative complications; however, these observations were made in studies with a small number of patients (77 in total) without a uniform selection process. In addition, most patients with comorbidities are unlikely to perform well on the 12MWT because of its extended testing time. In the two studies using the 6MWT, the 6MWD was found to be a significant predictor of surgical complications; however, the measured outcomes were defined differently between these two studies. Holden et al. defined poor surgical outcome as death within 90 days of surgery,42 whereas Pierce et al. defined it as inclusive of all postoperative complications.41 The total number of patients in these studies is also small (77 patients). Additionally, patients were instructed to perform the 6MWT multiple times as part of their evaluation (twice by Holden et al.42 and three times by Pierce et al.,41 with the longest 6MWD used for analysis). Since the publication of these studies, a learning effect has also been shown to have a significant impact on the 6MWD,23,24 guidelines for the 6MWT have been developed,23 and performance of practice tests is no longer recommended in most settings.43

The two studies we identified37,38 included a larger number of patients. However, the study by Nakagawa et al.38 assessed the 6MWD as a predictor of and not postoperative complications. The 6MWT is often performed as a submaximal test, and although the 6MWD has been correlated with in different patient populations,24 including patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and those with pulmonary fibrosis, it is unlikely to be a strong predictor of in patients with lung cancer who do not have severe comorbidities owing to its self-paced nature (this hypothesis has been confirmed by a recent study by Granger et al. in 20 patients with stage I through IIIB lung cancer39). The American Thoracic Society recommends that the 6MWT be used in complementary fashion and not as a substitute for CPET.43 The study by Marjanski et al.,37 although involving the largest number of patients with the 6MWT in the preoperative evaluation setting, was analyzed retrospectively.

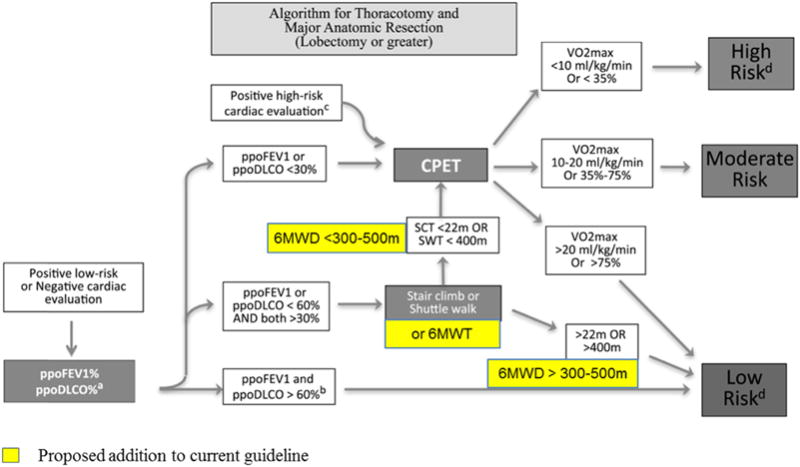

Despite these limitations, the 6MWT appears to have a role in the preoperative evaluation of lung cancer resection. A 6MWD threshold of more than 300 to 500 m appears to predict a lower risk for perioperative complications. This finding should be confirmed with additional studies before wider adoption in clinical practice (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Proposed addition of the 6MWT to the physiologic evaluation of patients with lung cancer for further studies. 6MWD, 6-minute walk distance; 6MWT, 6-minute walk test; DLCO, diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; ppoDLCO predicted postoperative DLCO; ppoFEV1, predicted postoperative FEV1; SCT, stair-climbing test; SWT, shuttle walk test; , maximal oxygen consumption. (a) For pneumonectomy candidates, perfusion scan is suggested to calculate ppoFEV1 or ppoDLCO (ppo values = preoperative values ×(1 − fraction of total perfusion for resected lung). For lobectomy patients, segmental counting is indicated to calculate ppoFEV1 or ppoDLCO (ppo values = preoperative values ×(1 − y/z), where y is the number of functional or unobstructed lung segments to be removed and z is the total number of functional segments. (b) Cutoff chosen based on indirect evidence and expert consensus opinion. (c) For patients with a positive high-risk cardiac evaluation deemed to be safe to proceed to resection, both pulmonary function test and cardiopulmonary exercise test are suggested for a more precise definition of risk. (d) Definition of risk: Low risk: The expected risk of mortality is below 1%. Major anatomic resection can be safely performed in this group. Moderate risk: Morbidity and mortality rates may vary according to the values of split lung functions, exercise tolerance, and extent of resection. Risks and benefits of the resection should be thoroughly discussed with the patient. High risk: The risk of mortality after standard major anatomic resection may be higher than 10%. Considerable risk of severe cardiopulmonary morbidity and residual function loss is expected. Patients should be counseled about alternative surgical (minor resections or minimally invasive surgery) or nonsurgical options.32 Modified from Brunelli et al.32 with permission.

After Lung Cancer Surgery

Exercise testing has also been used in patients after lung cancer therapy. We identified 15 studies involving three different exercise tests: CPET (nine studies), 6MWT (five studies), and SCT (two studies). Most studies involved postoperative patients. We divided our summaries according to different time frames after surgery: 1 to 3 months; 3 to 6 months; 6 to 12 months; and longer than 12 months (Table 5).

Table 5.

Selected Studies on Exercise Testing after Lung Cancer Resection Surgery

| Postsurgical Time Point/Selected Study |

Patient Population | Exercise Test/Instrument |

Findings | other Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mo: Nagamatsu et al.44 | 164 patients (149 lobectomy, 5 bilobectomy, 5 pneumonectomy) | CPET | improved significantly to 88% (±19%) of the preoperative baseline | FEV1, FVC, and DLCO improved significantly to ~70% of baseline |

| 1–3 mo: Brunelli et al.46 | 156 patients (144 lobectomy, 12 pneumonectomy) | SF-36 questionnaire | Physical scale was reduced compared with preoperative value at 1 mo (51 vs. 45, p < 0.0001), and recovered at 3 mo (51 vs. 52, P = 0.2) | Mental and social scores were unchanged after surgery compared with preoperative scores |

| 1–3 mo: Brunelli et al.45 | 200 patients (180 lobectomy, 20 pneumonectomy) | SCT to estimate | After lobectomy, was unchanged at 1 mo (96% of preoperative value)

and 3 mo (97%) After pneumonectomy, significantly improved (p < 0.05) to 87% of preoperative value at 1 mo and 89% at 3 mo |

After lobectomy, FEV1 and

DLCO significantly improved (p <

0.005) to 80% and 82% of preoperative values,

respectively at 1 mo, and 84% and 89% at 3

mo After pneumonectomy, FEV1 and DLCO significantly improved (p < 0.005) to 65% and 75% of preoperative values, respectively at 1 mo, and 66% and 80% at 3 mo |

| 3–6 mo: Nugent et al.47 | 53 patients (13 pneumonectomy) | CPET | was reduced by 28% (23.9 ± 1.5 vs. 17.2 ± 1.7 mL/kg/min, p < 0.01) in patients undergoing pneumonectomy (n = 13) but unchanged after thoracotomy alone (n = 13), wedge-resection (n = 13), and lobectomy (n = 14) | FEV1 and DLCO % predicted was significantly reduced (p < 0.05) by 26% and 30%, respectively, after pneumonectomy |

| 3 and > 6 mo: Nezu et al.48 | 82 patients (62 lobectomy, 20 pneumonectomy) | CPET | After lobectomy, decreased significantly at 3 mo and improved after more than

6 mo but did not reach preoperative values After pneumonectomy decreased significantly at 3 mo and did not recover thereafter on average, decreased 13.3% after lobectomy and 28.1% after pneumonectomy |

After lobectomy, FEV1 and VC

decreased significantly at 3 mo and improved after more than 6 mo but

did not reach preoperative values After pneumonectomy FEV1 and VC decreased significantly at 3 mo and did not recover thereafter |

| 12 mo: Wang et al.49 | 28 patients (19 lobectomy, 5 pneumonectomy, 4 segmentectomy) | CPET |

decreased significantly (p < 0.05) after

pneumonectomy (by 20%) and lobectomy (by 12%), but not

after segmentectomy on average, decreased significantly by 2.1 mL/kg/min (from 18.5 ± 4.0 to 16.3 ± 4.8 mL/kg/min, 11%) |

FEV1 decreased significantly after

pneumonectomy (by 23%), lobectomy (by 9%), and

segmentectomy (by 10%) FVC decreased significantly after pneumonectomy (by 28%) and lobectomy (by 13%) but not segmentectomy DLCO decreased significantly after pneumonectomy (by 33%), lobectomy (by 22%), and segmentectomy (by 9%) |

| Minimum 5 years: Deslauriers et al.50 | 100 postpneumonectomy patients | 6MWT | 6MWD was 83 ± 17% of predictive values; 19 out of 91 patients had lower than expected normal values | Compared to preoperative values,

FEV1 % predicted decreased significantly by

30%, FVC by 14%, and DLCO by

33% SPAP was mildly elevated at 36 ± 9 mm Hg; abnormal diaphragmatic motion detected in 88 patients; dyspnea was mild in 47 patients, moderate in 24 patients, and severe in 3 patients |

| Mean 5.5 ± 4.2 years: Vainshelboim et al.51 | 17 postpneumonectomy patients | CPET, 6MWT |

was 48 ± 17% of predicted (11.5 ±

3.3 mL/kg/min) 6MWD was 89 ± 25% of predicted (490 ± 15m) |

FEV1 was 46 ± 14%, FVC 55 ± 13%, DLCO 53 ± 18% of predicted SPAP mildly elevated at 38 ± 12 mm Hg |

6MWD, 6-minute walk distance; 6MWT, 6-minute walk test; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise testing; DLCO, diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; SCT, stair-climbing test; SPAP, systolic pulmonary arterial pressure; VC, vital capacity; , peak/maximal oxygen consumption; mo, month.

At 1 month after surgery, Nagamatsu et al.44 assessed 164 patients (91% lobectomy) and found that decreased and subsequently improved significantly to 88% of the preoperative baseline. In contrast, Brunelli et al.45 assessed 180 postlobectomy patients and found that (estimated by the SCT) did not change at 1 and 3 months after the operation; however, after pneumonectomy, decreased significantly and improved to 87% of the preoperative value at 1 month and 89% at 3 months. Self-reported physical composite scales have also shown that patients’ physical capacity decreased at 1 month after their operation but recovered at 3 months.46

At 3 to 6 months, Nugent et al.47 assessed 53 patients and found that was reduced by 28% after pneumonectomy whereas it was unchanged after thoracotomy alone, wedge resection, and lobectomy. In a larger study, Nezu et al.48 assessed 82 patients and found that after lobectomy, decreased significantly at 3 months and improved after more than 6 months but did not reach preoperative values; after pneumonectomy, decreased at 3 months and did not recover thereafter.

At 12 months, the largest study assessed 28 patients and found that decreased significantly after pneumonectomy and lobectomy but not after segmentectomy.49 At a minimum of 5 years, Deslauriers et al.50 found that the 6MWD was approximately 83% of predicted values in postpneumonectomy patients, with 19 out of 91 patients having less than expected age- and sex-adjusted normal values. In a similar study, Vainshelboim et al.51 assessed 17 postpneumonectomy patients (mean time 5.5 years after surgery) and found reductions in at approximately 48% of predicted values and 6MWD at approximately 89% of predicted values.

After lung resection, therefore, most patients appear to recover exercise capacity by 3 months. However, there appear to be subgroups of patients with extended recovery beyond 3 months. Those who do not recover by 6 months tend to remain limited beyond that time. Postpneumonectomy patients tend to have poorer recovery of exercise capacity compared with nonpneumonectomy patients and can have persistent limitations beyond 5 years. Long-term evaluations of exercise capacity and health status, including patient-reported function and dyspnea (especially in those receiving lobectomy, chemotherapy, and/or radiotherapy), are lacking.

Lung Cancer Prognosis

Exercise testing has also been used to predict survival in patients with lung cancer. We found 13 such studies involving CPET (nine studies), 6MWT (four studies), and SCT (two studies).

In patients undergoing evaluation for surgical resection, two large studies evaluated exercise testing and prognosis after surgery. Brunelli et al.52 studied the association between performance on the SCT and survival in 296 patients with stage I non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (mean SCT height 20 m). They reported that an SCT height greater than 18 m was an independent predictor of survival (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.5, p = 0.02), along with diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) and pathologic tumor stage. In a larger study involving CPET, Jones et al.53 investigated the association between and survival in 398 patients with stage I through III lung cancer (mean of 15.8 mL/kg/min), and found that compared with those with a less than 12.8 mL/kg/min, the adjusted HR for all-cause mortality was 0.64 for patients with a 15.5 mL/kg/min, and 0.56 for those with a greater than 19.1 mL/kg/min.

In patients with advanced lung and breast cancer, Jones et al.54 conducted a pilot study to assess the safety and feasibility of CPET. In 85 patients who underwent CPET, three patients (3.5%) were found to have positive electrocardiographic changes suggestive of ischemia, whereas asymptomatic, nonsignificant changes in ST segment developed in 12 patients with NSCLC (26.0%) and 17 patients with breast cancer (43.6%); in two patients adverse events developed during the test. In another study, Jones et al.55 assessed the prognostic value of the 6MWD in 118 patients with stage IIIB to IV NSCLC (mean 6MWD 396 m); they found the 6MWD to be an independent predictor of survival, with each 50-m improvement in the 6MWD associated with a 13% reduction in the risk for death. Compared with patients with a 6MWD less than 358.5 m, patients with a 6MWD greater than 450 m had an adjusted HR for all-cause mortality of 0.48.

In another study involving patients with advanced lung cancer, Kasymjanova et al.56 enrolled 64 consecutive patients with stage III to IV NSCLC who were undergoing doublet platinum-based chemotherapy (mean initial 6MWD of 420 m); they found that a 6MWD greater than 400 m was the only variable associated with improved survival in multivariable analyses (HR = 0.44, p = 0.001). In 45 patients who were able to complete the 6MWT both before and after chemotherapy, the mean 6MWD decreased after two cycles of chemotherapy from 462 m to 422 m (p = 0.01).

The aforementioned studies suggest that exercise capacity is a strong predictor of survival in patients with various clinical stages of lung cancer who are undergoing various modes of therapy. CPET testing appears to be well tolerated by patients with clinical stage I through III disease but may be difficult for patients with stage IV disease. The 6MWT appears to be a suitable test for evaluation of exercise capacity in patients with advanced lung cancer who are undergoing systemic therapy. The clinical implication of exercise testing outside of the preoperative evaluation setting cannot be accurately determined from the studies performed to date.

Assessment of Efficacy of Exercise Training Programs

Exercise interventions are known to increase exercise capacity in patients with chronic lung diseases. In the population of patients with lung cancer, we identified 15 studies involving exercise testing as a tool to assess the efficacy of exercise-based interventions: CPET (10 studies) and 6MWT (eight studies). All studies involved patients before or after resection, except for two that involved patients with advanced-stage lung cancer.

Edvardsen et al.57 conducted a single-blind, randomized controlled trial involving high-intensity endurance and strength training in 61 patients (clinical stage I through III) at 5 to 7 weeks after a resection. In an intention-to-treat analysis the exercise group had a greater increase in , DLCO, muscular strength, total muscle mass, functional fitness, and quality of life (QoL) compared with the control group.

In patients with stage III to IV lung cancer who were undergoing systemic chemotherapy, Quist et al.58 prospectively studied the benefits of a 6-week supervised group exercise intervention. A total of 114 patients were recruited; however, 43 (37.7%) did not perform their 6-week test point on account of disease progression (n = 10), lack of energy (n = 12), or refusal to participate in the training (n =21). In those who completed the study, the program resulted in improvement in (1.3 to 1.4 liters/min, p = 0.0003), 6MWD (527–561 m, p ≤ 0.001), and muscle strength. Patients also scored better on the social and emotional well-being scales; anxiety was statistically improved, whereas depression was not.

In a study of patients with adenocarcinoma who were receiving targeted therapy, Hwang et al.59 randomized 24 patients to an exercise program or standard care. They reported a significant increase in (+1.6 mL/kg/min, p < 0.005) in the exercise group (n =13) with no change in the control group. There were no changes in QoL scores; however, the exercise group displayed a significant improvement in dyspnea as well as decreased fatigue compared with baseline.

These studies suggest that exercise training interventions can improve exercise capacity in patients with lung cancer at various clinical stages. Exercise tests appear to be sensitive in detecting changes in exercise capacity in these patients. The 6MWT seems to be tolerated better than CPET, notably in patients with advanced disease.

Practical Considerations

There is ongoing debate as to which exercise test should be used in the population of patients with lung cancer. A few practical considerations are worth mentioning. Because of severe comorbidities and/or safety concerns, some patients with lung cancer are not able to perform exercise tests. For instance, Brunelli et al. found that 45 of 391 patients (11.5%) undergoing SCT for preoperative evaluation were unable to perform the test on account of musculoskeletal disease (26 patients), neurologic impairment (11), cardiovascular disease (seven), blindness (two), or psychiatric illness (one).60 In a similar but smaller study, Epstein et al. found that 14 of 74 patients (18.9%) undergoing CPET for preoperative evaluation for lung resection were unable to perform the test owing to musculoskeletal disease (seven), neurologic impairment (three), peripheral vascular disease (one), or psychiatric illness (one).61 Interestingly, in both studies, the inability to perform the test was associated with worse outcomes (increased risk for morbidity and mortality).60,61 CPET appeared to be less well tolerated and more likely to be difficult for patients with advanced lung cancer.

In addition to patient tolerance, the complexities and availability of the tests should be taken into consideration. CPET is substantially more complicated than simple field tests, with greater equipment and technical expertise requirements and often complex interpretation strategies.20 As such, it is not widely available in all institutions. The 6MWT, although readily available and easy to perform, is often a submaximal test because of its self-paced nature. Although patients can have a steady-state profile after 3 minutes of testing,23 those without significant coexisting pulmonary or cardiac disease are unlikely to approach their . The benefits of the 6MWT include the availability of standards for reproducibility and interpretation between various institutions.43 In addition, age- and sex-specific reference standards and minimally significant differences have been proposed.23,24 Like the 6MWT, the SCT is also self-paced. The lack of standardization (i.e., stair height) makes results difficult to interpret between different locations and institutions. The ISWT is externally paced and therefore can be used to estimate by increasing the walking speed. Although there are also set standards and proposed reference values for performance and interpretation of the ISWT,23,24 it is not readily available in many of the exercise laboratories in the United States.

A Proposed Conceptual Framework for Exercise Testing

Exercise tests can be used to assess patients’ exercise capacities and, to a reasonable extent, their ability to tolerate the necessary stresses induced by lung cancer treatment. Their use in risk stratification for lung cancer resection, specifically with direct or indirect measures of , is fairly well established. Conceptually, physiologic parameters from maximal exercise testing (CPET or ISWT) may be more predictive of outcomes, including postoperative functional limitation, after surgical stresses that are acute, intensive, and short-lived. In contrast, for stresses that are slow in onset, less intensive, and longer-lasting (e.g., chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy), submaximal exercise tests (e.g., 6MWT, the endurance shuttle walking test) in addition to maximal exercise testing may potentially be predictive of outcomes.

Traditionally, survival is the principal outcome in many studies assessing therapeutic efficacy in lung cancer. In the absence of good alternative treatment options, relatively high risks (including the risk for perioperative death) have been taken to achieve the potential benefit of a cure. As such, older studies of lung cancer resection reported much higher rates of surgical mortality. As surgical techniques and technological advancements have allowed for safer, better-tolerated treatment modalities, other outcome measures besides death or serious complications need to be taken into account in clinical decision making. In patients with advanced lung cancer, the risks of systemic therapy, including clinical worsening, have to be balanced against the potential benefits of reducing tumor burden and symptoms. The risks of chemotherapy are not well understood and are poorly defined. In a landmark study, palliative care in patients with advanced lung cancer resulted in improved survival,62 potentially because of less exposure to systemic therapy in patients too ill to tolerate the toxic effects. Advancements in targeted therapies and immunotherapy for advanced-stage lung cancer allow for better-tolerated systemic therapy. There are, however, continued challenges when faced with mutations conferring resistance to treatment and eventually leading to systemic chemotherapy. As such, other assessments of health, including evaluation of exercise capacity, long-term disabilities, and health-related QoL, should also be considered in clinical outcome measurements. Exercise testing to evaluate exercise capacity can help identify high-risk patients being considered not only for surgical resection but potentially also for systemic therapy and/or subsequent therapy.

Although there appear to be associations between certain physiologic exercise measures and clinical outcomes, clinical decision making, especially regarding binary decisions, (e.g., surgery versus no surgery), is complex and multifaceted. No single variable or algorithms involving exercise testing should be used in the decision making process. Instead, an individualized/patient-oriented and multidisciplinary approach is likely to lead to better clinical outcomes.

Areas for Further Studies

Currently, there is no accepted definition of “prohibitive risk” for lung cancer therapy.63 Assessments of health in patients in whom lung cancer has been newly diagnosed and in lung cancer survivors can help better define both prohibitive and relative risks by identifying long-term disabilities resulting from the associated treatments. Such assessments might be useful to risk-stratify patients being considered for therapy, facilitate postoperative/treatment care, and potentially improve outcomes and QoL. Rehabilitation programs and/or exercise-based interventions appear to improve outcomes in certain subgroups of patients; however, their appropriate use is not well studied or understood, and randomized studies assessing efficacy are lacking. Exercise testing could help to identify those with impaired exercise capacity who are most likely to derive benefit from these programs/interventions. Lastly, it is unclear whether clinical decisions regarding interventions based on any one form of exercise testing discussed in the previous sections can lead to improved outcomes/overall survival in the lung cancer population.

Studies are underway seeking to bridge the existing gap between the simple field tests and CPET. During the 6MWT, patients have been fitted with a lightweight metabolic monitor and face mask to provide simultaneous measurements of , , , and breathing reserve.64 Portable hemodynamic monitoring with impedance cardiography during the 6MWT has also been used to assess patients with pulmonary hypertension.65 To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies involving the 6MWT or other simple field tests coupled with these technologies have been applied in patients with lung cancer. In addition, there may be promise in the predictive ability of certain autonomic measures (e.g., heart rate recovery at the end of exercise66,67) and other physiologic measures from CPET (e.g., ventilatory inefficiency68) that may be further validated in larger populations.

Conclusions

The take-home points from this article are as follows: (1) patients with lung cancer are at risk for exercise limitations due to comorbidities, the effects of lung cancer, and/or its treatment; (2) exercise capacity is prognostic and predictive of outcomes in lung cancer, and it is most useful to risk-stratify patients undergoing evaluation for lung cancer resection; (3) the 6MWT, CPET, SCT, and SWT have been used most frequently, each with its own limitations in availability, feasibility, standardization/interpretation, and relationships to outcome; and (4) rehabilitation programs and/or exercise-based interventions to improve exercise capacity can improve lung cancer outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Data

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of the Journal of Thoracic Oncology at www.jto.org and at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2016.04.021.

References

- 1.Howington JA, Blum MG, Chang AC, et al. Treatment of stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e278S–e313. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donington J, Ferguson M, Mazzone P, et al. American College of Chest Physicians and Society of Thoracic Surgeons consensus statement for evaluation and management for high-risk patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2012;142:1620–1635. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carver JR, Shapiro CL, Ng A, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical evidence review on the ongoing care of adult cancer survivors: cardiac and pulmonary late effects. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3991–4008. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardy D, Liu CC, Cormier JN, et al. Cardiac toxicity in association with chemotherapy and radiation therapy in a large cohort of older patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1825–1833. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lenihan DJ, Kowey PR. Overview and management of cardiac adverse events associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Oncologist. 2013;18:900–908. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reck M, van Zandwijk N, Gridelli C, et al. Erlotinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: efficacy and safety findings of the global phase IV Tarceva Lung Cancer Survival Treatment study. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1616–1622. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f1c7b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janne PA, Yang JC, Kim DW, et al. AZD9291 in EGFR inhibitor-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1689–1699. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakagawa K, Kudoh S, Ohe Y, et al. Postmarketing surveillance study of erlotinib in Japanese patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): an interim analysis of 3488 patients (POLARSTAR) J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1296–1303. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182598abb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi L, Tang J, Tong L, et al. Risk of interstitial lung disease with gefitinib and erlotinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Lung Cancer. 2014;83:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw AT, Kim DW, Mehra R, et al. Ceritinib in ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1189–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gadgeel SM, Gandhi L, Riely GJ, et al. Safety and activity of alectinib against systemic disease and brain metastases in patients with crizotinib-resistant ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer (AF-002JG): results from the dose-finding portion of a phase 1/2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1119–1128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70362-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2018–2028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sculier JP, Chansky K, Crowley JJ, et al. The impact of additional prognostic factors on survival and their relationship with the anatomical extent of disease expressed by the 6th Edition of the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors and the proposals for the 7th Edition. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:457–466. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31816de2b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dajczman E, Kasymjanova G, Kreisman H, et al. Should patient-rated performance status affect treatment decisions in advanced lung cancer? J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:1133–1136. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318186a272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arena R, Sietsema KE. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the clinical evaluation of patients with heart and lung disease. Circulation. 2011;123:668–680. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.914788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wasserman K, Hansen JE, Sue DY, et al. Exercise testing and interpretation: an overview. In: Wasserman K, Hansen JE, Sue DY, et al., editors. Principles of Exercise Testing and Interpretation: Including Pathophysiology and Clinical Applications. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Thoracic Society. American College of Chest Physicians. ATS/ACCP statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:211–277. doi: 10.1164/rccm.167.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bokemeyer C, Oechsle K, Hartmann JT. Anaemia in cancer patients: pathophysiology, incidence and treatment. Eur J Clin Invest. 2005;35(suppl 3):26–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2005.01527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christensen JF, Jones LW, Andersen JL, et al. Muscle dysfunction in cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:947–958. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holland AE, Spruit MA, Troosters T, et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:1428–1446. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00150314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh SJ, Puhan MA, Andrianopoulos V, et al. An official systematic review of the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society: measurement properties of field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:1447–1478. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00150414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novoa NM, Varela G, Jimenez MF, et al. Value of the average basal daily walked distance measured using a pedometer to predict maximum oxygen consumption per minute in patients undergoing lung resection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39:756–762. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ninan M, Sommers KE, Landreneau RJ, et al. Standardized exercise oximetry predicts postpneumonectomy outcome. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:328–332. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(97)00474-8. discussion 332–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bagg LR. The 12-min walking distance; its use in the preoperative assessment of patients with bronchial carcinoma before lung resection. Respiration. 1984;46:342–345. doi: 10.1159/000194711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chidler H, Couraud L. Test of preoperative unilateral occlusion of the pulmonary artery at rest and during exercise. Its place in the study of functional respiratory and right and left cardiac tolerance of extensive pulmonary excisions. Ann Chir. 1986;40:602–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagamatsu Y, Takamori S, Hayashida R, et al. Pulmonary capacity in lung cancer patients prior to lung resection– comparison of the unilateral pulmonary artery occlusion test with expired gas analysis during exercise testing. Kurume Med J. 1996;43:273–277. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.43.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pierce RJ, Sharpe K, Johns J, et al. Pulmonary artery pressure and blood flow as predictors of outcome from lung cancer resection. Respirology. 2005;10:620–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2005.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierce RJ, Pretto JJ, Rochford PD, et al. Lobar occlusion in the preoperative assessment of patients with lung cancer. Br J Dis Chest. 1986;80:27–36. doi: 10.1016/0007-0971(86)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunelli A, Kim AW, Berger KI, et al. Physiologic evaluation of the patient with lung cancer being considered for resectional surgery: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e166S–e190. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brunelli A, Charloux A, Bolliger CT, et al. ERS/ESTS clinical guidelines on fitness for radical therapy in lung cancer patients (surgery and chemo-radiotherapy) Eur Respir J. 2009;34:17–41. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00184308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim E, Baldwin D, Beckles M, et al. Guidelines on the radical management of patients with lung cancer. Thorax. 2010;65(suppl 3):iii1–iii27. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.145938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao K, Yu PM, Su JH, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing screening and pre-operative pulmonary rehabilitation reduce postoperative complications and improve fast-track recovery after lung cancer surgery: a study for 342 cases. Thorac Cancer. 2015;6:443–449. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fang Y, Ma G, Lou N, et al. Preoperative maximal oxygen uptake and exercise-induced changes in pulse oximetry predict early postoperative respiratory complications in lung cancer patients. Scand J Surg. 2014;103:201–208. doi: 10.1177/1457496913509235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marjanski T, Wnuk D, Bosakowski D, et al. Patients who do not reach a distance of 500 m during the 6-min walk test have an increased risk of postoperative complications and prolonged hospital stay after lobectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;47:e213–e219. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezv049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakagawa T, Chiba N, Saito M, et al. Clinical relevance of decreased oxygen saturation during 6-min walk test in preoperative physiologic assessment for lung cancer surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;62:620–626. doi: 10.1007/s11748-014-0413-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Granger CL, Denehy L, Parry SM, et al. Which field walking test should be used to assess functional exercise capacity in lung cancer? An observational study. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15:89. doi: 10.1186/s12890-015-0075-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Markos J, Mullan BP, Hillman DR, et al. Preoperative assessment as a predictor of mortality and morbidity after lung resection. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139:902–910. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.4.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pierce RJ, Copland JM, Sharpe K, et al. Preoperative risk evaluation for lung cancer resection: predicted postoperative product as a predictor of surgical mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:947–955. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.4.7921468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holden DA, Rice TW, Stelmach K, et al. Exercise testing, 6-min walk, and stair climb in the evaluation of patients at high risk for pulmonary resection. Chest. 1992;102:1774–1779. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.6.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagamatsu Y, Iwasaki Y, Hayashida R, et al. Factors related to an early restoration of exercise capacity after major lung resection. Surg Today. 2011;41:1228–1233. doi: 10.1007/s00595-010-4441-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brunelli A, Xiume F, Refai M, et al. Evaluation of expiratory volume, diffusion capacity, and exercise tolerance following major lung resection: a prospective follow-up analysis. Chest. 2007;131:141–147. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brunelli A, Socci L, Refai M, et al. Quality of life before and after major lung resection for lung cancer: a prospective follow-up analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:410–416. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nugent AM, Steele IC, Carragher AM, et al. Effect of thoracotomy and lung resection on exercise capacity in patients with lung cancer. Thorax. 1999;54:334–338. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.4.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nezu K, Kushibe K, Tojo T, et al. Recovery and limitation of exercise capacity after lung resection for lung cancer. Chest. 1998;113:1511–1516. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.6.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang JS, Abboud RT, Wang LM. Effect of lung resection on exercise capacity and on carbon monoxide diffusing capacity during exercise. Chest. 2006;129:863–872. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.4.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deslauriers J, Ugalde P, Miro S, et al. Long-term physiological consequences of pneumonectomy. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;23:196–202. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vainshelboim B, Fox BD, Saute M, et al. Limitations in exercise and functional capacity in long-term postpneumonectomy patients. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2015;35:56–64. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brunelli A, Pompili C, Berardi R, et al. Performance at preoperative stair-climbing test is associated with prognosis after pulmonary resection in stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:1796–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jones LW, Watson D, Herndon JE, 2nd, et al. Peak oxygen consumption and long-term all-cause mortality in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:4825–4832. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones LW, Eves ND, Mackey JR, et al. Safety and feasibility of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in patients with advanced cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jones LW, Hornsby WE, Goetzinger A, et al. Prognostic significance of functional capacity and exercise behavior in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012;76:248–252. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kasymjanova G, Correa JA, Kreisman H, et al. Prognostic value of the six-minute walk in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:602–607. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31819e77e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Edvardsen E, Skjonsberg OH, Holme I, et al. High-intensity training following lung cancer surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2015;70:244–250. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quist M, Adamsen L, Rorth M, et al. The impact of a multidimensional exercise intervention on physical and functional capacity, anxiety, and depression in patients with advanced-stage lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Integr Cancer Ther. 2015;14:341–349. doi: 10.1177/1534735415572887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hwang CL, Yu CJ, Shih JY, et al. Effects of exercise training on exercise capacity in patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving targeted therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:3169–3177. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1452-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brunelli A, Sabbatini A, Xiume’ F, et al. Inability to perform maximal stair climbing test before lung resection: a propensity score analysis on early outcome. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;27:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Epstein SK, Faling LJ, Daly BD, et al. Inability to perform bicycle ergometry predicts increased morbidity and mortality after lung resection. Chest. 1995;107:311–316. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lim E, Beckles M, Warburton C, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing for the selection of patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer: friend or foe? Thorax. 2010;65:847–849. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.133181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tueller C, Kern L, Azzola A, et al. Six-minute walk test enhanced by mobile telemetric cardiopulmonary monitoring. Respiration. 2010;80:410–418. doi: 10.1159/000319834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tonelli AR, Alkukhun L, Arelli V, et al. Value of impedance cardiography during 6-minute walk test in pulmonary hypertension. Clin Transl Sci. 2013;6:474–480. doi: 10.1111/cts.12090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ha D, Choi H, Zell K, et al. Association of impaired heart rate recovery with cardiopulmonary complications after lung cancer resection surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149:1168–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stephens Ha D, Choi KH, et al. eart rate recovery and survival in patients undergoing stereotactic body radiotherapy for treatment of early-stage lung cancer. J Radiosurg SBRT. 2015;3(3):193–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Torchio R, Guglielmo M, Giardino R, et al. Exercise ventilatory inefficiency and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease undergoing surgery for non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.