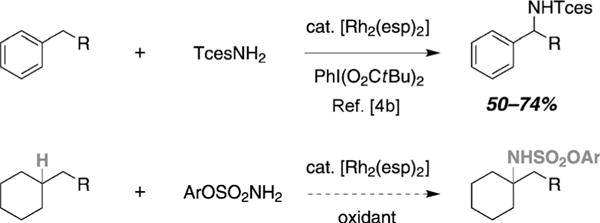

The preparation of tetrasubstituted amine derivatives through intermolecular amination of tertiary C–H bonds remains an outstanding challenge in methods development given the allure of such a technology for streamlining synthesis (Figure 1).[1,2] While there exist a small number of reports in which this reaction has been demonstrated, almost all examples require superstoichiometric amounts of substrate.[3] Owing to recent insights gained through mechanistic studies, we now report a general method for the selective amination of tertiary C–H centers.[4] The reaction is operationally simple, tolerant of most common functional groups, and delivers a protected amine that is easily liberated. The influence of different nitrogen sources on product selectivity is also highlighted along with mechanistic studies that implicate steric effects as a principal determinant of site selectivity.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of tetrasubstituted amine derivatives through intermolecular, Rh-catalyzed tertiary C–H bond amination. TcesNH2 = 2,2,2-trichloroethoxysulfonamide; esp = α,α,α,α′-tetramethyl-1,3-benzenedipropionate.

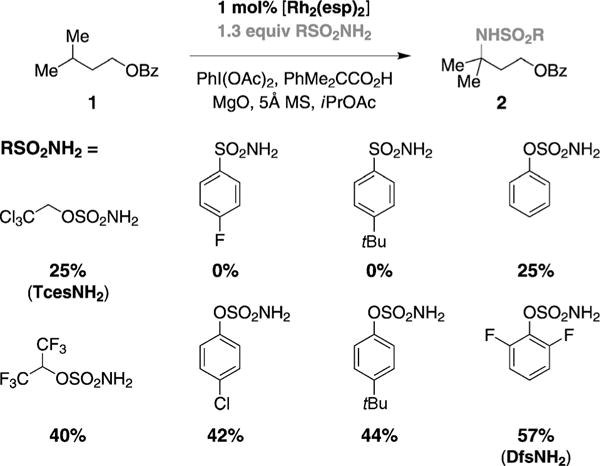

We have recently provided evidence that the dirhodium tetracarboxylate catalyst, [Rh2(esp)2],[5] when subjected to C–H amination reaction conditions, undergoes competitive one-electron oxidation to a red, mixed-valent Rh2+/Rh3+ dimer.[4,6] Fortuitously, this species is reduced under the reaction conditions by tBuCO2H, a byproduct of the hypervalent iodine oxidant used to drive the amination event.[4a] Our understanding of this process has resulted in a modification of the reaction conditions to include PhMe2CCO2H, a carboxylic acid additive that serves as an effective reducing agent and offers improved catalyst turnover numbers in intermolecular amination reactions of benzylic substrates.[4a,7] Application of these conditions to the oxidation of isoamyl-benzoate 1 (1.0 equiv), however, furnishes only a small amount of the desired amine 2 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Influence of sulfonamide on reaction efficiency.

Careful analysis of the oxidation of 1 has revealed that the nitrogen source, 2,2,2-trichloroethoxysulfonamide (TcesNH2), is largely consumed in spite of the poor yield of 2.[8] The low mass recovery of TcesNH2 suggests that oxidation of the methylene center of the alkoxysulfonamide may be occurring. For this reason, we have examined alternative sulfonamide derivatives, including aryl- and phenolic-based reagents. Results from reactions performed with [Rh2(esp)2] (1mol%), PhI(OAc)2, and PhMe2CCO2H (0.s equiv) demonstrate enhanced catalyst turnover numbers (TONs) when aryloxysulfonamide reagents are employed (Figure 2).[9] Of these, the sulfamate prepared from 2,6-difluorophenol, DfsNH2, has proven optimal. Empirical studies reveal that the inclusion of both MgO and 5 Å molecular sieves further improves catalyst TONs, as does an initial substrate concentration of 1.0 M.[10–12] The reaction mixture appears as a green slurry from which product 2 can be isolated in 57% yield (12 h).[13,14]

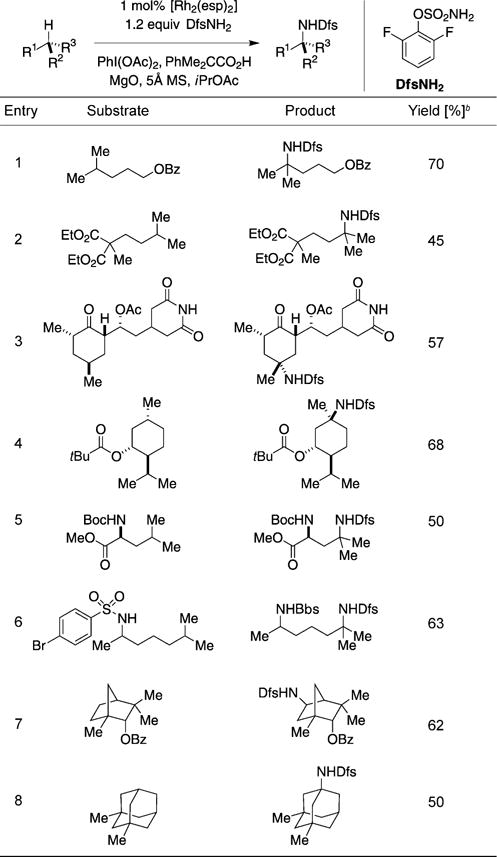

A collection of disparate substrates possessing tertiary C–H bonds and assorted functional groups can be oxidized smoothly using DfsNH2 as the nitrogen source (Table 1). As a general rule, the mass balance of this reaction is primarily accounted for by unreacted starting material and the reported product. The amination reaction is responsive to the proximity of electron-withdrawing groups to the site of oxidation; product yields generally improve as the distance between the C–H bond to be oxidized and polar substituents increases (Table 1, entries 1,2).[4b,15] Both electronic and steric elements can be exploited to influence positional selectivity in molecules containing multiple tertiary C–H centers. Oxidation of the acylated natural product cycloheximide is exemplary in this regard, as only a single product isomer is generated despite the presence of four tertiary C–H bonds (Table 1, entry 3). Other examples include the menthol derivative shown in entry 4 for which reaction occurs exclusively at the C–H bond of the cyclohexyl tertiary carbon center. The direct preparation of substituted diamino acids and 1,5-diamines in a single step from common starting materials is also of particular note (Table 1, entries 5,6).

Table 1.

A generalized procedure for tertiary C–H bond amination with a limiting amount of alkane substrate.[a]

|

Reactions performed in iPrOAc with 1.0 equiv of substrate, 1.2 equiv of DfsNH2, 2.0 equiv of Phi(OAc)2 and MgO, 0.5 equiv of PhMe2CCO2H, 5 Å MS, and 1 mol% of [Rh2(esp)2].[16]

Yields are based on isolated material following chromatography on silica gel. Bbs = p-bromobenze-nesulfonyl.

Oxidation of a bridged bicyclic substrate (Table 1, entry 7) furnishes the product of secondary methylene oxidation in 62% yield and as a single stereoisomer. Selectivity for amination of the exo-C–H bond can be rationalized on the basis of both steric and stereoelectronic effects. The inability to functionalize the bridgehead C–H bond is unsurprising, since Rh-catalyzed electrophilic amination processes generally disfavor reactions of C–H bonds that are rich in s-orbital character.[17] By contrast, bridgehead C–H bonds in unstrained bicyclic systems, such as those found in adamantane, smoothly engage in this reaction. In the example shown in entry 8, the product is a masked form of memantine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist that is used clinically for the treatment of late-stage Alzheimer’s disease.[3d,18]

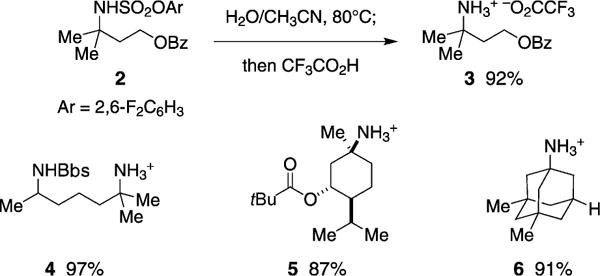

C–H amination products derived from DfsNH2 may be free based in refluxing aqueous CH3CN; no additional additives are required to effect this transformation. Selective cleavage of the aryloxysulfonamide occurs without incident to benzoate, pivaloate, and arenesulfonyl functional groups (Figure 3). The product amines are isolated as trifluoroacetate salts after purification by reverse-phase HPLC.

Figure 3.

Hot aqueous CH3CN effects amine deprotection.

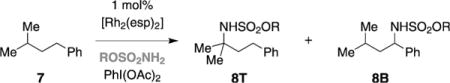

Comparative amination studies conducted with DfsNH2 and TcesNH2 indicate that the choice of the nitrogen source can influence reaction selectivity. We have noted previously that oxidation of isoamylbenzene 7 with TcesNH2 affords a 1:8 product ratio favoring benzylic sulfonamide 8B (Table 2, entry 1). Under the same reaction conditions, the sulfamate ester derived from neopentyl alcohol generates a 1:4 product ratio of 8T and 8B (Table 2, entry 2). Conversely, reaction of 7 and DfsNH2 furnishes a 1.5:1 mixture of 8T and 8B, slightly favoring the product of tertiary C–H amination (Table 2, entry 3). Other sulfamate derivatives (Table 2, entries 4,5), which are competent for intermolecular tertiary C–H oxidation (see Figure 2), give results similar to DfsNH2 (i.e., ca. 1:1 8T/8B).

Table 2.

influence of sulfamate ester on product selectivity.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | ROSO2NH2 | 8T | 8B |

| 1 | CI3CCH2OSO2NH2 | 1 | 8 |

| 2 | Me3CCH2OSO2NH2 | 1 | 4 |

| 3 | 2,6-F2C6H3OSO2NH2 | 1.5 | 1 |

| 4 | (CF3)2CHOSO2NH2 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | ptBuC6H4OSO2NH2 | 1 | 1 |

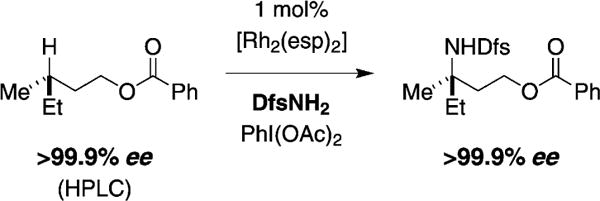

We wish to understand whether the observed, albeit small, variations in product selectivity (i.e., 8T versus 8B) manifest as a result of 1) steric interactions between the nitrogen source, catalyst, and substrate, or 2) a change in mechanism between stepwise or concerted asynchronous C–H oxidation. When using either DfsNH2 or TcesNH2 as the nitrogen source,[4b] stereospecific insertion into an optically active tertiary substrate is noted (Figure 4). Such a finding is consistent with C–H functionalization occurring through a concerted asynchronous nitrenoid insertion event or a stepwise C–H abstraction/radical rebound pathway involving a short-lived radical pair. The plausibility of the latter pathway for [Rh2(esp)2]-catalyzed intermolecular C–H amination with TcesNH2 is supported by recent density functional theory calculations by Bach and co-workers,[19] and by desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (DESI-MS) experiments from Perry et al.[20] DESI-MS studies have identified two dirhodium nitrene species that differ in oxidation state (i.e., Rh2+/Rh2+ versus Rh2+/Rh3+), at least one of which is capable of H-atom abstraction from C–H bonds (e.g., CH2Cl2, C–H bond dissociation energy (BDE) = 97 kcalmol−1).[21]

Figure 4.

Enantiospecific insertion into a C–H bond at a tertiary carbon center.

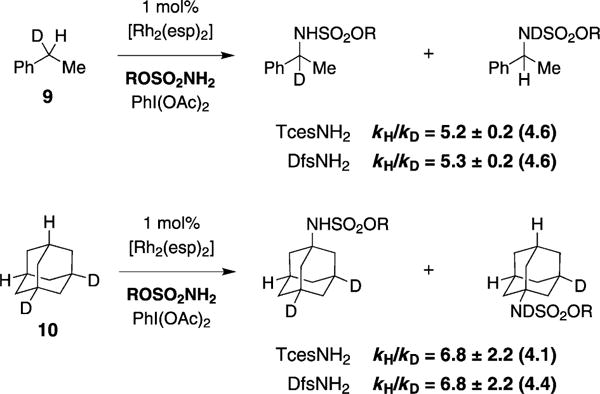

To further query the properties of TcesNH2 and DfsNH2, a comparative kinetic isotope measurement has been conducted with monodeuterated ethyl benzene and dideuteroadamantane (Figure 5). These data establish that KIEs for both sulfamate agents are equivalent within error, irrespective of the nature of the C–H bond undergoing oxidation (i.e., benzylic or tertiary). The magnitudes of the recorded KIEs are surprisingly large (5.2–6.9, 13CNMR analysis) and are suggestive of a transition structure for intermolecular C–H amination in which extensive C–H bond breaking has occurred.[22] Ruthenium- and copper-catalyzed nitrene-insertion reactions displaying similar primary KIE values are generally believed to follow a stepwise rather than concerted asynchronous course.[3c,23,24] A measured KIE of 2.6 ± 0.2 has been determined for an analogous Rh2(OAc)4-catalyzed intramolecular amination event,[25] for which a large body of experimental and theoretical evidence supports a concerted nitrenoid C–H insertion event.

Figure 5.

Primary KIE values for intermolecular C–H amination, as determined by 13C NMR integration. Values in parentheses are obtained by HRMS; see the Supporting information for details.

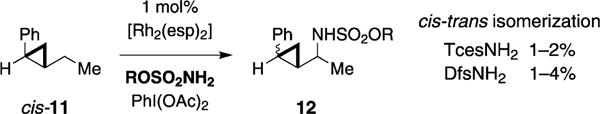

Amination reactions using a cyclopropane clock, cis-11, have been performed in an attempt to identify a short-lived radical intermediate on the pathway to product (Figure 6). The rate constant for ring opening of trans-11 has been measured at 7 × 1010 s−1, which is appropriate for detection of radicals having picosecond lifetimes.[26] In the amination event with cis-11, generation of 1–4 % of trans-cyclopropane 12 gives evidence for the intermediacy of a cyclopropylcarbinyl radical, which undergoes subsequent reversible cyclopropane ring opening. The identical outcomes for TcesNH2 and DfsNH2 in this, the KIE, and stereospecificity experiments lead us to conclude that steric effects between the nitrenoid complex and substrate principally govern product selectivity (see Table 2). While it appears that the cyclopropane clock results are consistent with a stepwise process for intermolecular C–H amination,[19] DESI-MS[20] and UV/Vis spectroscopic data[4a,6] are commensurate with the presence of more than one dirhodium complex following initiation of the reaction. Thus, it is possible that different catalyst species present in solution at disparate concentrations promote C–H amination through mechanistically distinct pathways.

Figure 6.

Cis-trans isomerization implicates transient cyclopropyl-car-binyl radical formation.

We have developed an effective process for generating tetrasubstituted amine derivatives through selective, intermolecular tertiary C–H bond amination. The optimized reaction is performed with limiting amounts of substrate, 1 mol % of commercially available [Rh2(esp)2], and inexpensive PhI(OAc)2 as the terminal oxidant. The identification of aryloxysulfonamides, in particular DfsNH2, as functional nitrogen sources has been an instrumental find. Competition studies with substrates possessing disparate C–H bond types reveal variations in product selectivity, which derive solely from the choice of sulfamate ester. Future studies are aimed at providing a unified mechanistic model for Rh-catalyzed C–H amination that explains these data and that guides our efforts to further advance such technologies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

We are grateful to Theresa McLaughlin (Stanford University Mass Spectrometry) for help with mass spectrometry experiments and to Prof. Barry Trost for allowing use of instrumentation. Funding for this project was provided by the National Science Foundation Center for Stereoselective C–H Functionalization (CCHF, CHE–1205646). J.L.R. is a Ruth Kirschstein NIH postdoctoral fellow (F32GM089033) and a fellow of the Center for Molecular Analysis and Design (CMAD) at Stanford. D.N.Z. was supported by an Achievement Rewards for College Scientists (ARCS) Foundation Stanford Graduate Fellowship. Generous research support has also been provided to our lab from Pfizer and Novartis.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201304238.

Contributor Information

Prof. Jennifer L. Roizen, Department of Chemistry, Duke University, 3236 French Science Center, 124 Science Drive, Durham, NC 27708-0346 (USA)

David N. Zalatan, Department of Chemistry, Stanford University, CA 94305-5080 (USA), jdubois@stanford.edu

Prof. J. Du Bois, Department of Chemistry, Stanford University, CA 94305-5080 (USA)

References

- 1.Special issue:; a) C–H Functionalization in Organic Synthesis. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40(4) doi: 10.1039/c1cs90010b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yu J-Q, Shi Z, editors. Topics in Current Chemistry. Springer; Berlin: 2010. C–H Activation; pp. 1–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Recent reviews of carbenoid- and nitrenoid-mediated C–H insertion:; a) Lebel H. In: Catalyzed Carbon-Heteroatom Bond Formation. Yudin A, editor. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2011. pp. 137–156. [Google Scholar]; b) Dequirez G, Pons V, Dauban P. Angew Chem. 2012;124:7498–7510. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:7384–7395. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Gephart RT, III, Warren TH. Organometallics. 2012;31:7728–7752. [Google Scholar]; d) Roizen JL, Harvey ME, Du Bois J. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:911–922. doi: 10.1021/ar200318q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Stokes BJ, Driver TG. Eur J Org Chem. 2011:4071–4088. [Google Scholar]; f) Doyle MP, Duffy R, Ratnikov M, Zhou L. Chem Rev. 2009;109:704–724. doi: 10.1021/cr900239n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Collet F, Dodd RH, Dauban P. Chem Commun. 2009:5061–5074. doi: 10.1039/b905820f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Diaz-Requejo MM, Perez PJ. Chem Rev. 2008;108:3379–3394. doi: 10.1021/cr078364y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A recent example of intramolecular C–H functionalization:; Hennessy ET, Betley TA. Science. 2013;340:591–595. doi: 10.1126/science.1233701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selected examples of aminations of C–H bonds at tertiary carbon centers:; a) Lescot C, Darses B, Collet F, Retailleau P, Dauban P. J Org Chem. 2012;77:7232–7240. doi: 10.1021/jo301563j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ochiai M, Miyamoto K, Kaneaki T, Hayashi S, Nakanishi W. Science. 2011;332:448–451. doi: 10.1126/science.1201686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Collet F, Lescot C, Liang C, Dauban P. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:10401–10413. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00283f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Barman DN, Liu P, Houk KN, Nicholas KM. Organometallics. 2010;29:3404–3412. [Google Scholar]; e) Baba H, Togo H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:2063–2066. [Google Scholar]; f) Liu Y, Che CM. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:10494–10501. [Google Scholar]; g) Liang C, Collet F, Robert-Peillard F, Müller P, Dodd RH, Dauban P. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:343–350. doi: 10.1021/ja076519d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Huard K, Lebel H. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:6222–6230. doi: 10.1002/chem.200702027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4 a).Zalatan DN, Du Bois J. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7558–7559. doi: 10.1021/ja902893u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fiori KW, Du Bois J. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:562–568. doi: 10.1021/ja0650450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espino CG, Fiori KW, Kim M, Du Bois J. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15378–15379. doi: 10.1021/ja0446294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6 a).Kornecki KP, Berry JF. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:5827–5832. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kornecki KP, Berry JF. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2012:562–568. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nörder A, Herrmann P, Herdtweck E, Bach T. Org Lett. 2010;12:3690–3692. doi: 10.1021/ol101517v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.TcesNH2 was first employed as a nitrene precursor in alkene aziridination reactions, see:; Guthikonda K, Du Bois J. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13672–13673. doi: 10.1021/ja028253a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Under the same reaction conditions, para-substituted benzene sulfonamides fail to give more than traces of product 2.

- 10.MgO is frequently used as an additive in C–H amination reactions. For an initial report, see:; Espino CG, Du Bois J. Angew Chem. 2001;113:618–620. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:598–600. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molecular sieves have previously been employed in C–H amination reactions, see, for example:; Zalatan DN, Du Bois J. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9220–9221. doi: 10.1021/ja8031955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.For nonpolar substrates that fail to dissolve completely in this solvent, 1:1 mixtures of iPrOAc with benzene or trifluoro-methyltoluene are also found to be acceptable. An initial report of iPrOAc as a solvent for C–H amination:; Chan J, Baucom KD, Murry JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14106–14107. doi: 10.1021/ja073872a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Product conversions are not demonstrably improved at higher catalyst loadings (e.g., 2 mol %) or through portionwise addition of catalyst.

- 14.Despite the persistent green color of the reaction mixture after 12 h of stirring, control experiments suggest that the rhodium complex(es) is no longer catalytically active; however, some fraction of unreacted iodine oxidant remains.

- 15.Similar observations have been noted in carbenoid and oxenoid C–H functionalization reactions. For leading references, see:; a) Chen MS, White MC. Science. 2007;318:783–787. doi: 10.1126/science.1148597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Davies HML, Hansen T, Churchill MR. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3063–3070. [Google Scholar]; For a discussion on the influence of strain on site selectivity, see:; c) Chen K, Eschenmoser A, Baran PS. Angew Chem. 2009;121:9885–9888. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:9705–9708. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Product isolation by chromatography on silica gel can be complicated by the presence of PhMe2CCO2H, see the Supporting Information for details.

- 17.A similar observation has been noted in C–H hydroxylation reactions with dioxiranes, see:; Mello R, Fiorentino M, Fusco C, Curci R. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:6749–6757. [Google Scholar]

- 18 a).Madhra MK, Sharma M, Khanduri CH. Org Process Res Dev. 2007;11:922–923. [Google Scholar]; b) Reddy JM, Prasad G, Raju V, Ravikumar M, Himabindu V, Reddy GM. Org Process Res Dev. 2007;11:268–269. [Google Scholar]; c) Henkel JG, Hane JT, Gianutsos G. J Med Chem. 1982;25:51–56. doi: 10.1021/jm00343a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Sasaki T, Eguchi S, Katada T, Hiroaki O. J Org Chem. 1977;42:3741–3743. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norder A, Warren SA, Herdtweck E, Huber SM, Bach T. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:13524–13531. doi: 10.1021/ja3066682. Additionally, Bach and co-workers report a primary KIE of 4.8 ± 0.7 at a benzylic methylene position for the [Rh2(esp)2]-catalyzed insertion reaction involving TcesNH2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perry RH, Cahill TJ, Roizen JL, Du Bois J, Zare RN. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:18295–18299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207600109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo YR. Comprehensive Handbook of Chemical Bond Energies. Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton: pp. 19–145. [Google Scholar]

- 22.A KIE of 3.5 has been measured for Rh2(OAc)4-catalyzed amination of 10 with p-NO2C6H4SO2N = IPh, see:; Nägeli I, Baud C, Bernardinelli G, Jacquier Y, Moran M, Muller P. Helv Chim Acta. 1997;80:1087–1105. A KIE of 4.5 was recorded for [Rh2{(S)-nta}4]-catalyzed insertion of 9 with N-(p-toluenesul-fonyl)-p-toluenesulfonimidamide as the nitrogen source; see reference [3b] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Primary KIE values ranging from 4.8–11 have been reported for Ru-catalyzed, intermolecular C–H amination:; Leung SK-Y, Tsui WM, Huang JS, Che CM, Liang JL, Zhu N. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16629–16640. doi: 10.1021/ja0542789. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Badiei YM, Dinescu A, Dai X, Palomino RM, Heinemann FW, Cundari TR, Warren TH. Angew Chem. 2008;120:10109–10112. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:9961–9964. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harvey ME, Musaev DG, Du Bois J. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:17207–17216. doi: 10.1021/ja203576p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi SY, Toy PH, Newcomb M. J Org Chem. 1998;63:8609–8613. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.