Abstract

Objective

Previous studies involving large administrative datasets have revealed regional variation in the demographics of patients selected for carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and carotid artery stenting (CAS), but lacked clinical granularity. This study aims to evaluate regional variation in patient selection and operative technique for carotid artery revascularization using a detailed clinical registry.

Methods

All patients who underwent CEA or CAS from 2009 to 2015 were identified in the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI). De-identified regional groups were used to evaluate variation in patient selection, operative technique and perioperative management. Chi-square analysis was used to identify significant variation across regions.

Results

A total of 57,555 carotid artery revascularization procedures were identified. Of these, 49,179 underwent CEA (asymptomatic: median 56%; range 46–69%, P < .01) and 8,376 underwent CAS (asymptomatic: median 36%; range 29–51%, P < .01). There was significant regional variation in the proportion of asymptomatic patients being treated for carotid stenosis < 70% in CEA (3–9%, P < .01) versus CAS (3–22%, P < .01). There was also significant variation in the rates of intervention for asymptomatic patients over the age of 80 (CEA: 12–27%, P < .01; CAS: 8–26%, P< .01). Pre-operative CTA/MRA in the CAS cohort also varied widely (31–83%, P < .01), as did pre-operative medical management with combined aspirin/statin (CEA: 53–77%, P < .01; CAS: 62–80%, P < .01). In the CEA group, the use of shunt (36–83%, P < .01), protamine (32–89%, P < .01) and patch varied widely (87–99%, P < .01). Similarly, there was regional variation in frequency of CAS done without a protection device (1–8%, P < .01).

Conclusion

Despite clinical benchmarks aimed at guiding management of carotid disease, wide variation in clinical practice exists, including the proportion of asymptomatic patients being treated using CAS and pre-operative medical management. Additional intra-operative variables including the use of a patch and protamine during CEA and use of a protection device during CAS displayed similar variation, in spite of clear guidelines. Quality improvement projects could be directed towards improved adherence to benchmarks in these areas.

Introduction

Carotid artery revascularization is one of the most commonly performed procedures, with over 250,000 performed annually worldwide.1 Much like other common vascular procedures, such as abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, previous studies have identified wide variation in patient selection and treatment in these patient populations.2–4 Carotid endarterectomy (CEA) has long been the standard approach, however, recently there has been increased implementation in the less invasive alternative, carotid artery stenting (CAS).5 Previous studies using administrative databases have identified a trend toward increasing utilization of CAS, and have shown significant geographic variation within it.6, 7

According to Birkmeyer et al., variation itself falls into two major categories: acceptable and unwarranted.8 Acceptable variation includes variables such as patient comorbidities and operative techniques, where guidelines are unclear, or do not exist. Unwarranted variation reflects areas where best-practice measures have been created and guidelines are in place to serve as benchmarks for quality care. They reviewed a number of common surgical procedures, including CEA, and determined that discretion of the clinician was the largest factor responsible for variation.

The Dartmouth Atlas evaluated trends in variation, specifically in carotid revascularization, and showed that though there was an increasing utilization of CAS, there was significant regional variation in its application.9 Additional research involving Medicare patients corroborated these results and showed a high degree of variability in practice patterns.4, 10 This study builds on those previously performed by providing additional data, such as operative details, which the others were lacking.

With the evolution in healthcare management and greater focus on consistency in quality patient care, there has been a rising interest in establishing solid, evidence-based benchmarks to guide physician care. The Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) has identified such standards for carotid revascularization procedures.11, 12 These pertain to patient factors, such as the recommendation for medical management in asymptomatic patients with stenosis less than 60%. Additionally, they have developed technical considerations, such as when to use CEA over CAS, the use of a patch during CEA and the use of a protection device during CAS. Although these guidelines exist, limited data are available regarding how routinely they are being utilized.12

Despite the variation in use of CAS, limited data have shown the variation in patient selection, operative technique and indications for intervention for carotid disease. Moreover, few studies have assessed how treatment compares to current quality benchmarks. We hypothesize significant variation exists across the regions with regards to patient selection and treatment of carotid artery revascularization. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the regional variation in baseline patient characteristics and comorbidities, indications for treatment, procedure selection and operative characteristics. Furthermore, we aim to compare current practice to those clinical benchmarks established by the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS). By evaluating the variation surrounding these factors, we identified areas where quality improvement efforts can focus on adherence to existing current guidelines, as well as direct further research to define best practices.

Methods

Database

The Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) was used to identify all patients who underwent carotid endarterectomy (CEA) or carotid artery stenting (CAS) from 2009–2015. The VQI is a national clinical registry developed by the SVS to help improve patient care. It represents a collaboration between 17 de-identified regional quality groups, involving over 300 hospitals and 1,300 physicians. Additional information regarding the registry can be found at www.vascularqualityinitiative.org/. The Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study, and patient consent was waived due to the de-identified nature of this dataset.

Variables

Variable definitions were set forth by the VQI and were not able to be altered. Patient demographics, comorbid conditions, pre-operative medications and operative details were identified for all patients. Symptomatic disease was defined as any history of ipsilateral ocular or cortical stroke or transient ischemic attack. The degree of stenosis was obtained from the ipsilateral internal carotid artery stenosis measurement. The modality to obtain this measurement is not listed in the registry.

SVS guidelines were then utilized to identify a subset of patients where CAS is preferred to CEA. This included symptomatic patients with stenosis > 50% who were considered high-risk for anatomical reasons (high lesions, tracheal stoma, or a history of previous radiation or ipsilateral surgery), or stenosis > 50% and severe coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics version 23 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL) and all figures were produced using GraphPad version 6.0 (La Jolla, CA). Chi-square analysis was used to compare variation across regions. Forest plots were used to represent the range of each variable across the 17 regions, depicted by a line containing symbols, each of which represents an individual region. Each region had a volume of greater than 100 of either procedure, and therefore were all analyzed individually. The vertical line on each plot represents the VQI median. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 57,555 carotid artery revascularizations were performed, consisting of 49,179 CEA and 8,376 CAS.

Patient Selection and Demographics

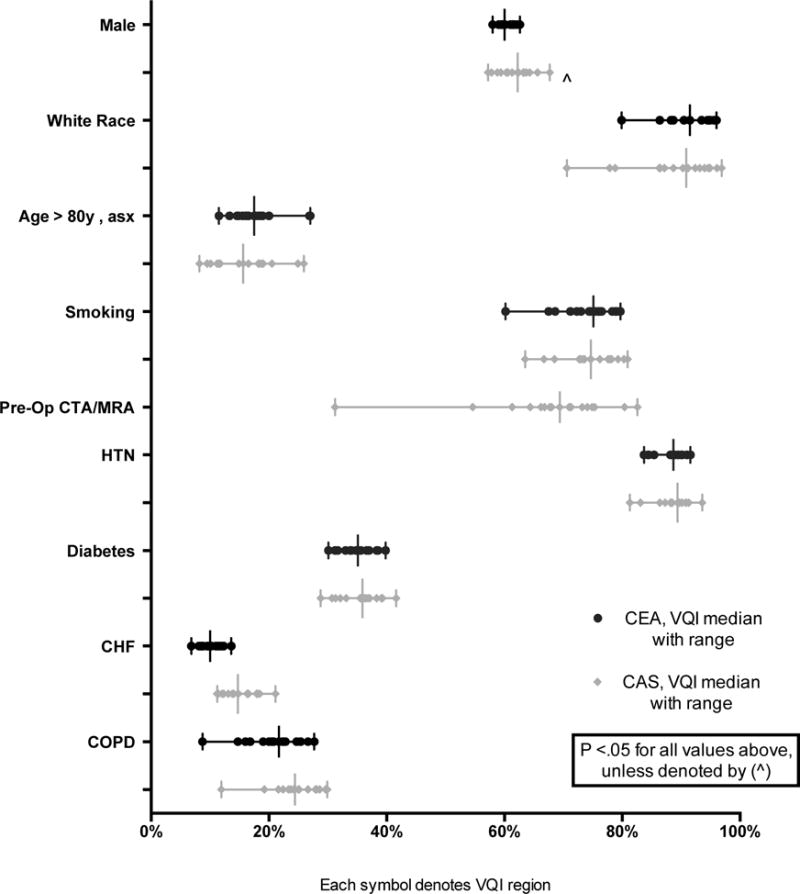

As depicted in Figure 1, significant variation was seen in the baseline characteristics among patients who underwent carotid artery revascularization. Male patients underwent the majority of these interventions across all regions, with significant variation noted only in the CEA population (58–63%, P = .03). The proportion of asymptomatic CEA and CAS patients over age 80 across regions ranged from 12–27% (P < .01) and 8–26% (P < .01), respectively. Wide variation was seen the proportion of white patients, ranging from 80–96% (P < .01) in CEA and 71–97% (P < .01) in the CAS. Patient comorbidities also reflected significant regional variation including: hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Smoking also varied widely across the regions (CEA: 60–80%, P < .01; CAS 64–81%, P < .01). Prior to undergoing CAS, the use of pre-operative CTA or MRA ranged from 31–83% (P < .01) across the regions.

Figure 1.

Pre-operative demographics and co-morbidities for patients undergoing CEA or CAS (each symbol on a line represents a VQI region with a vertical line for the median value)

Indications for Procedure

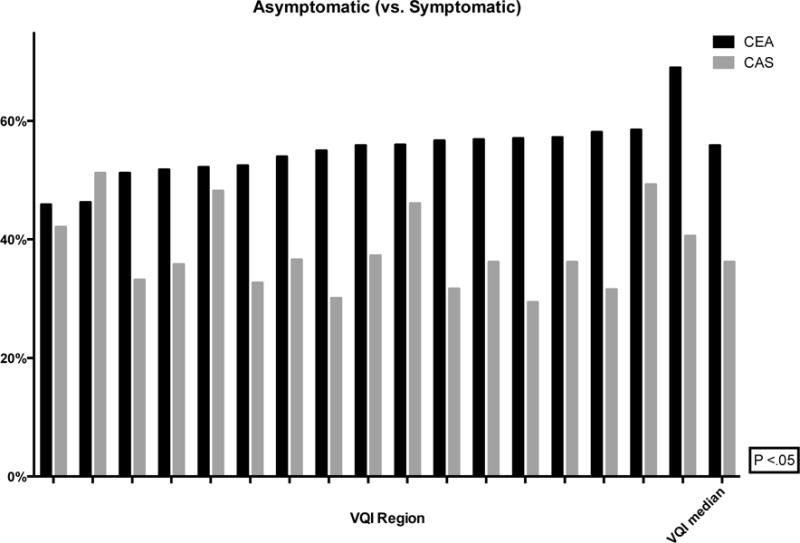

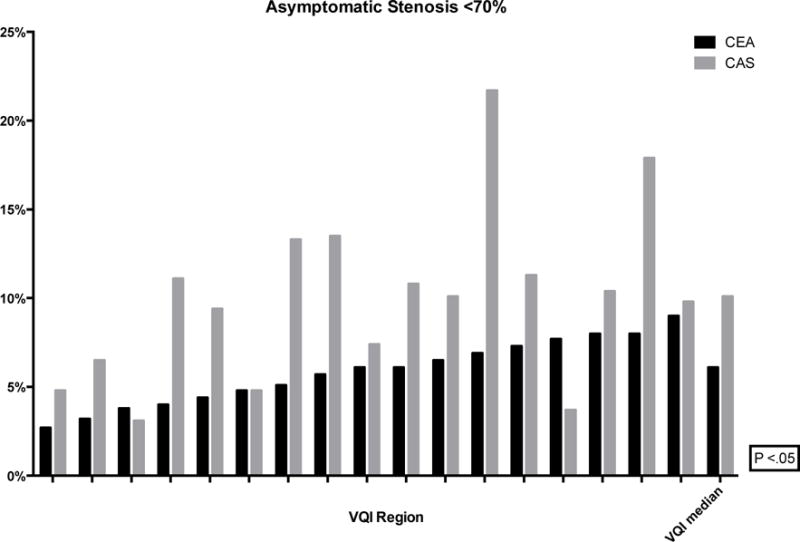

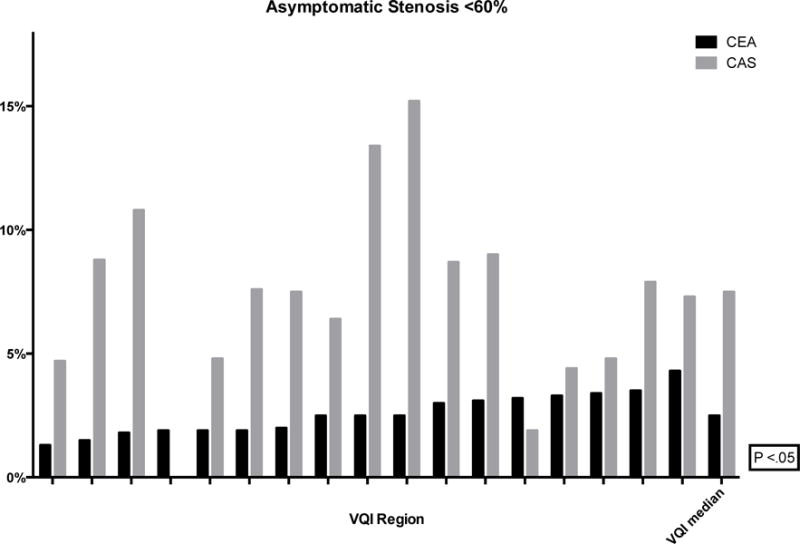

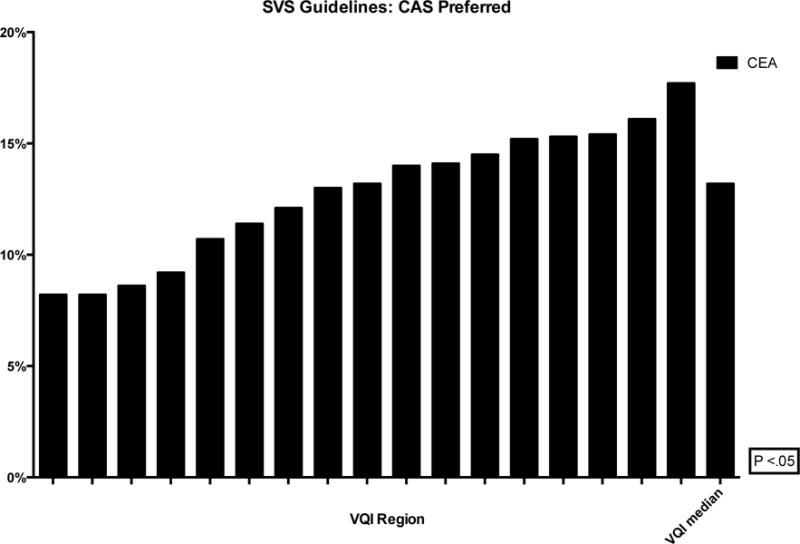

The proportion of CEA and CAS performed in asymptomatic patients ranged from 46–69% (P < .01) and 29–51% (P < .01), respectively (Figure 2). Within this population, the proportion of interventions performed for stenosis less than 70% ranged from 3–9% (P < .01) for CEA and 3–22% (P < .01) for CAS (Figure 3). Additionally, revascularization of asymptomatic patients with a stenosis less than 60% ranged from 1–4% for CEA (P < .01) and 0–15% for CAS (P < .01) (Figure 4). Finally, using the SVS guidelines to define optimal CAS patients, we found wide variation across regions of these patients undergoing CEA instead (8–18%, P < .01) (Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Proportion of asymptomatic (vs. symptomatic) patients undergoing CEA or CAS (de-identified VQI regions labeled on the x-axis with the median)

Figure 3.

Proportion of CEA and CAS performed for asymptomatic stenosis <70% (de-identified VQI regions labeled on the x-axis with the median)

Figure 4.

Proportion of CEA and CAS performed for asymptomatic stenosis <60% (de-identified VQI regions labeled on the x-axis with the median)

Figure 5.

Proportion of patients defined by SVS guidelines as optimal CAS patients who underwent CEA instead (de-identified VQI regions labeled on the x-axis with the median)

Operative Technique

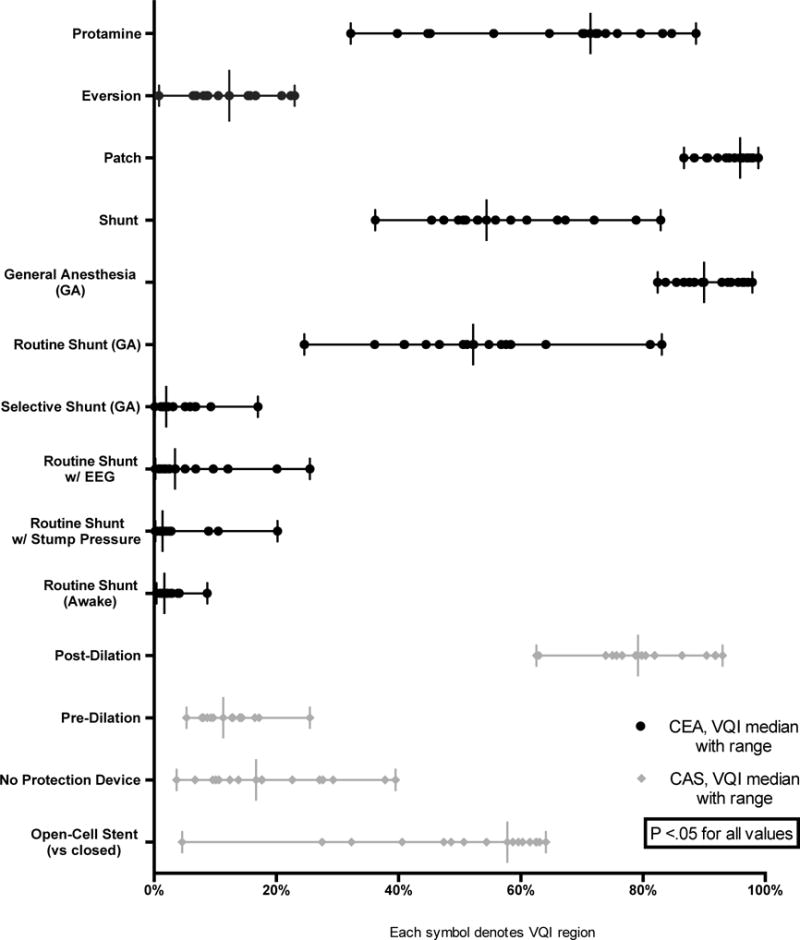

Among CEA patients, significant variation was found across the regions in the use of protamine (32–89%, P < .01), eversion (versus longitudinal) endarterectomy (1–23%, P < .01) and use of patch with longitudinal endarterectomy (87–99%, P < .01). The use of general anesthesia during CEA ranged from 82–98% (P < .01). Within the general anesthesia patients, significant differences were seen in routine shunt use (25–83%, P < .01) versus selective shunt use (0.1–17%, P < .01). Among patients with routine shunting, those who had EEG varied (0–26%, P < .01), as did those who had stump pressure measured (0–20%, P < .01) and those who were not under general anesthesia (0–9%, P < .01) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Operative details for patients undergoing CEA or CAS (each symbol on a line represents a VQI region with a vertical line for the median value)

During CAS, the proportion performed without use of a neurological protection device ranged from 4–40% (P < .01) across regions. Additionally, pre-stent arterial dilation and post-dilation rates varied from 5–26% (P < .01) and 63–93% (P < .01), respectively. Open-cell stents (versus closed) were utilized 5–65% (P < .01) of the time (Figure 6).

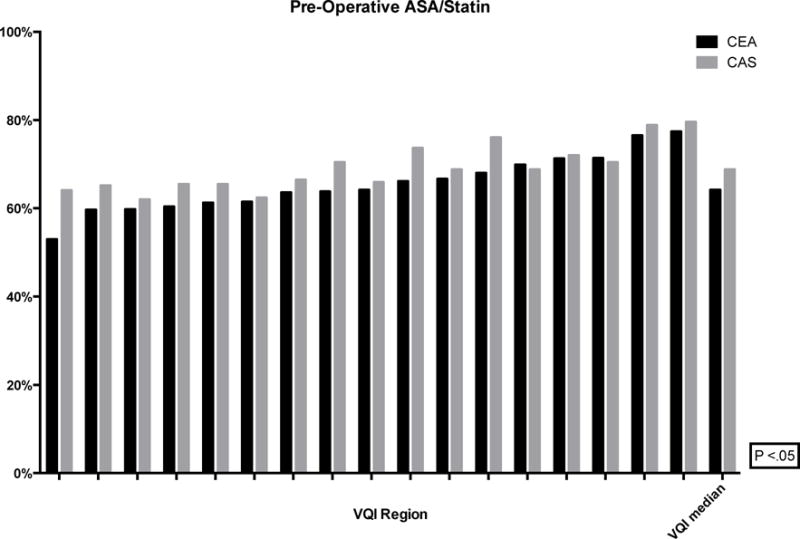

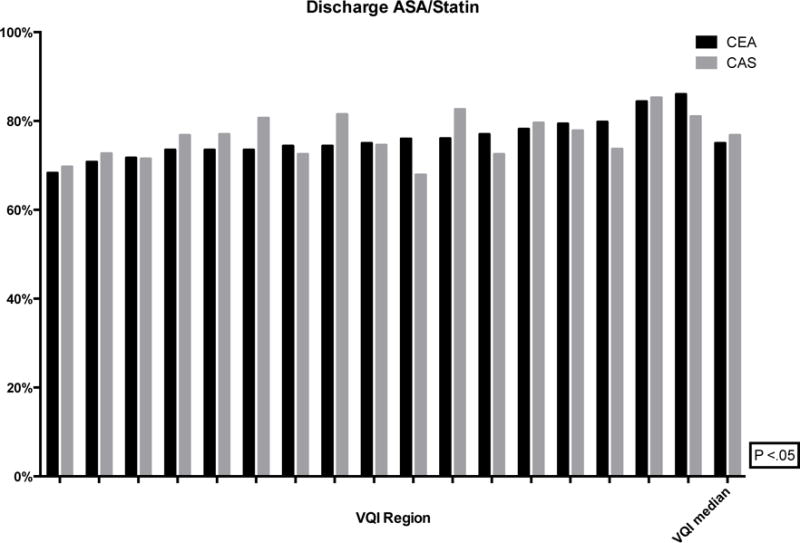

Medication Use

For both CEA and CAS, pre-operative medication use varied significantly: aspirin (CEA: 70–89%, P < .01; CAS: 78–93%, P < .01), P2Y12 antagonist (CEA: 21–39%, P < .01; CAS: 64–84%, P < .01) and statin (CEA: 72–86%, P < .01; CAS: 70–86%, P < .01). The proportion of CEA and CAS patients on optimal medical therapy pre-operatively, defined as both an anti-platelet and a statin, ranged from 53–77% and 62–80%, respectively (Figure 7). Likewise, at discharge, the rates varied from 68–86% and 68–85% for CEA and CAS patients, respectively (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Proportion of patients on pre-operative ASA and Statin (de-identified VQI regions labeled on the x-axis with the median)

Figure 8.

Proportion of patients discharged on ASA and Statin (de-identified VQI regions labeled on the x-axis with the median)

Discussion

In this study, we sought to review regional variation in carotid artery revascularization procedures across the United States, and found wide variation present throughout the regions of the VQI. Though some of the variation can be classified as acceptable and used for future projects to determine best practices, some of it represents unwarranted variation, based on existing practice guidelines.

SVS guidelines recommend medical management for asymptomatic patients with stenosis less than 60% or symptomatic patients with stenosis less than 50%. Randomized trials demonstrated not only a failure of the intervention to prevent strokes, but also increased morbidity from the intervention, as compared to medical therapy.13–16 Despite these clearly set guidelines, there was significant variation in interventions performed on asymptomatic patients with stenosis less than 60%, with as many as 4% of CEA patients and 15% of CAS patients. Currently, reimbursement is not provided for CAS for asymptomatic patients if the stenosis is determined to be less than 70%.17 Yet we found that in spite of this, there were between 3% and 22% of CAS patients who fell into this category. Within the CEA population, previous literature supports performing a patch angioplasty or eversion endarterectomy as opposed to primary closure, as well as the use of protamine to reduce bleeding complications.18–20 However, our study identified wide variation in both practices. Similarly, during CAS, embolic protection devices are recommended to reduce the risk of embolization.21–23 These events may represent unwarranted variation, where clear guidelines exist.

The SVS guidelines additionally contain recommendations for procedure selection. Several studies have assessed the utility of CAS in asymptomatic patients; however, there have been conflicting data. Consequently, the current guidelines do not recommend stenting for asymptomatic patients.12 Nonetheless, we found extensive regional variation in the use of CAS in the asymptomatic population. Due to conflicting data, as well as recent studies such as the Asymptomatic Carotid Trial (ACT) I, there is controversy within these recommendations and therefore do not represent unwarranted variation.24 The use CAS in the treatment of asymptomatic carotid disease is currently being investigated in multiple trials, including Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST) 2, and has become the number one high-impact clinical research priority.25–27 Conversely, for the symptomatic patient population, the SVS recommends CAS for symptomatic patients with stenosis > 50% who were considered high-risk for anatomical reasons (high lesions, tracheal stoma, or a history of previous radiation or ipsilateral surgery), or stenosis > 50% and severe coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Significant variation is present here as well, however, this is a lower level recommendation and is more dependent on specific patient factors, and therefore, may be considered more acceptable variation.

In CAS patients, there is a clear benefit for dual anti-platelet therapy.28–31 In CEA patients, the benefit of dual as compared to monotherapy is unclear, however, the use of both an aspirin and statin in both the CEA and CAS populations is considered optimal medical therapy.32–35 Consequently, the variation found in these areas is likely unwarranted. Certainly a small amount of variation should be expected, as some patients may not tolerate the medications or may be non-compliant, however these patients made up less than 1% of our population. Therefore, the degree of variation we discovered suggests there are other factors involved, such as provider preferences.

This study illustrates that profound variation, both acceptable and unwarranted, is present in patient selection and treatment of carotid artery revascularization procedures across the regions of the VQI. Previous research involving carotid disease in Medicare beneficiaries has shown that significant geographical differences exist for the treatment of this disease in the United States.6, 36 Additional studies utilizing large, administrative databases have noted regional variation in the rates of CEA versus CAS performed; these studies helped drive the randomized control trials that ultimately formed many of the current benchmark guidelines.3, 8, 37–39 This study not only confirmed the results of the previous work, but also gives us the ability to quantify several aspects of patient care, such as rates of adoption of best medical therapy, which show significant regional variation. This, in turn, helps to define areas for research efforts designed to improve adherence to guidelines. Established metrics like protamine and patch use among patients undergoing CEA or protection device used during CAS could be targets for regional quality improvement projects. For those metrics with acceptable variation but without clear best practice, such as operative variables and the proportion of symptomatic to asymptomatic patients, the presence of variation shown in this study could serve as an impetus to begin research projects to identify best practices. Additionally, even though these regions are all de-identified, each region, center and surgeon has access to their own data and can act upon their results. Every contributor can use their own data to compare to others in their region and across the country. Furthermore, regional quality groups, such as the VQI, may chose to act further upon areas where we have identified issues, or provide direct feedback. We are currently working on the second part of this project, which investigates the regional variation in the outcomes of carotid revascularization. Pending the results of this project, there may be even more influence on quality groups to provide individualized feedback.

This study has several important limitations to discuss. First, this is a retrospective analysis using prospectively collected data from the hospitals in the VQI. As is the case with large multicenter databases, there exists the potential for missing data and coding errors. To reduce these potential limitations, the VQI conducts an annual audit to review the clinical data submitted from their hospitals. Additionally, the variables are set within the database by the VQI and therefore we are unable to alter them to fit our study design. Given the de-identification of the dataset, we are unable to evaluate variation among the different hospitals and surgeons within each region. Additionally, we are unable to evaluate the potential influences of geographic location, such as being in high volume, urban regions versus rural areas. Aside from the database limitations, it is important to note that there is also natural geographic variation across patient populations that we cannot account for, such as access to healthcare and local provider preferences. Prior work involving geographic variation has the same pitfalls, and the SVS guidelines have subsequently been developed without factoring this in as well.3, 6, 9, 12, 36, 40

Conclusion

This study identified multiple areas in patient selection and treatment of carotid artery disease where significant variation exists, including procedure indications and operative techniques. In some of these areas, guidelines exist and deviation from them is reflective of the variation in practice patterns we have found. Additionally, there are still aspects of the care of patients with carotid disease that lack definitive evidence and as such future research is warranted. Quality improvement projects could be directed to improve adherence to guidelines that currently exist. Additionally, we have identified targets for future research to determine additional best practices.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Harvard-Longwood Research Training in Vascular Surgery NIH T32 Grant 5T32HL007734-22

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at the Society for Vascular Surgery Vascular Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, June 5–7, 2014.

References

- 1.Skerritt MR, Block RC, Pearson TA, Young KC. Carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery stenting utilization trends over time. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zettervall SL, Buck DB, Soden PA, Cronenwett JL, Goodney PP, Eslami MH, et al. Regional variation exists in patient selection and treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feasby TE, Quan H, Ghali WA. Geographic variation in the rate of carotid endarterectomy in Canada. Stroke. 2001;32(10):2417–22. doi: 10.1161/hs1001.096196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel MR, Greiner MA, DiMartino LD, Schulman KA, Duncan PW, Matchar DB, et al. Geographic variation in carotid revascularization among Medicare beneficiaries, 2003–2006. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(14):1218–25. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallaert JB, Nolan BW, Stone DH, Powell RJ, Brown JR, Cronenwett JL, et al. Physician specialty and variation in carotid revascularization technique selected for Medicare patients. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63(1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.08.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodney PP, Travis LL, Malenka D, Bronner KK, Lucas FL, Cronenwett JL, et al. Regional variation in carotid artery stenting and endarterectomy in the Medicare population. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(1):15–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.864736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groeneveld PW, Epstein AJ, Yang F, Yang L, Polsky D. Medicare’s policy on carotid stents limited use to hospitals meeting quality guidelines yet did not hurt disadvantaged. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(2):312–21. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birkmeyer JD, Sharp SM, Finlayson SR, Fisher ES, Wennberg JE. Variation profiles of common surgical procedures. Surgery. 1998;124(5):917–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huber TS, Seeger JM. Dartmouth Atlas of Vascular Health Care review: impact of hospital volume, surgeon volume, and training on outcome. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34(4):751–6. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.116969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nallamothu BK, Gurm HS, Ting HH, Goodney PP, Rogers MA, Curtis JP, et al. Operator experience and carotid stenting outcomes in Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2011;306(12):1338–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cronenwett JL, Kraiss LW, Cambria RP. The Society for Vascular Surgery Vascular Quality Initiative. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(5):1529–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ricotta JJ, Aburahma A, Ascher E, Eskandari M, Faries P, Lal BK, et al. Updated Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines for management of extracranial carotid disease. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54(3):e1–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST) Lancet. 1998;351(9113):1379–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnett HJ, Taylor DW, Eliasziw M, Fox AJ, Ferguson GG, Haynes RB, et al. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(20):1415–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811123392002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial C. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(7):445–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. JAMA. 1995;273(18):1421–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Services CfMM. Decision Memo for Carotid Artery Stenting (CAG-00085R) 2005 Available from: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=157&ver=29&NcaName=Carotid+Artery+Stenting+(1st+Recon)&bc=BEAAAAAAEAAA&&fromdb=true.

- 18.Bond R, Rerkasem K, Naylor AR, Aburahma AF, Rothwell PM. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of patch angioplasty versus primary closure and different types of patch materials during carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40(6):1126–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao P, De Rango P, Zannetti S. Eversion vs conventional carotid endarterectomy: a systematic review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;23(3):195–201. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2001.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stone DH, Nolan BW, Schanzer A, Goodney PP, Cambria RA, Likosky DS, et al. Protamine reduces bleeding complications associated with carotid endarterectomy without increasing the risk of stroke. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(3):559–64. 64 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.10.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garg N, Karagiorgos N, Pisimisis GT, Sohal DP, Longo GM, Johanning JM, et al. Cerebral protection devices reduce periprocedural strokes during carotid angioplasty and stenting: a systematic review of the current literature. J Endovasc Ther. 2009;16(4):412–27. doi: 10.1583/09-2713.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parodi JC, Schonholz C, Parodi FE, Sicard G, Ferreira LM. Initial 200 cases of carotid artery stenting using a reversal-of-flow cerebral protection device. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2007;48(2):117–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vos JA, van den Berg JC, Ernst SM, Suttorp MJ, Overtoom TT, Mauser HW, et al. Carotid angioplasty and stent placement: comparison of transcranial Doppler US data and clinical outcome with and without filtering cerebral protection devices in 509 patients. Radiology. 2005;234(2):493–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2342040119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenfield K, Matsumura JS, Chaturvedi S, Riles T, Ansel GM, Metzger DC, et al. Randomized Trial of Stent versus Surgery for Asymptomatic Carotid Stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(11):1011–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1515706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraiss LW, Conte MS, Geary RL, Kibbe M, Ozaki CK. Setting high-impact clinical research priorities for the Society for Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57(2):493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubin MN, Barrett KM, Brott TG, Meschia JF. Asymptomatic carotid stenosis: What we can learn from the next generation of randomized clinical trials. JRSM Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;3 doi: 10.1177/2048004014529419. 2048004014529419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rudarakanchana N, Dialynas M, Halliday A. Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial-2 (ACST-2): rationale for a randomised clinical trial comparing carotid endarterectomy with carotid artery stenting in patients with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38(2):239–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brott TG, Hobson RW, 2nd, Howard G, Roubin GS, Clark WM, Brooks W, et al. Stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of carotid-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):11–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Featherstone RL, Dobson J, Ederle J, Doig D, Bonati LH, Morris S, et al. Carotid artery stenting compared with endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis (International Carotid Stenting Study): a randomised controlled trial with cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(20):1–94. doi: 10.3310/hta20200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mas JL, Chatellier G, Beyssen B, Branchereau A, Moulin T, Becquemin JP, et al. Endarterectomy versus stenting in patients with symptomatic severe carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(16):1660–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massop D, Dave R, Metzger C, Bachinsky W, Solis M, Shah R, et al. Stenting and angioplasty with protection in patients at high-risk for endarterectomy: SAPPHIRE Worldwide Registry first 2,001 patients. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;73(2):129–36. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke W, Berger PB, Black HR, Boden WE, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(16):1706–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, Cimminiello C, Csiba L, Kaste M, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9431):331–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16721-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hindler K, Shaw AD, Samuels J, Fulton S, Collard CD, Riedel B. Improved postoperative outcomes associated with preoperative statin therapy. Anesthesiology. 2006;105(6):1260–72. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200612000-00027. quiz 89–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindenauer PK, Pekow P, Wang K, Gutierrez B, Benjamin EM. Lipid-lowering therapy and in-hospital mortality following major noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 2004;291(17):2092–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodney PP, Travis LL, Nallamothu BK, Holman K, Suckow B, Henke PK, et al. Variation in the use of lower extremity vascular procedures for critical limb ischemia. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(1):94–102. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.962233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chassin MR, Kosecoff J, Park RE, Winslow CM, Kahn KL, Merrick NJ, et al. Does inappropriate use explain geographic variations in the use of health care services? A study of three procedures. JAMA. 1987;258(18):2533–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibbs RG, Todd JC, Irvine C, Lawrenson R, Newson R, Greenhalgh RM, et al. Relationship between the regional and national incidence of transient ischaemic attack and stroke and performance of carotid endarterectomy. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1998;16(1):47–52. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(98)80091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J, Peto C, Peto R, Potter J, et al. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9420):1491–502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones WS, Patel MR, Dai D, Subherwal S, Stafford J, Calhoun S, et al. Temporal trends and geographic variation of lower-extremity amputation in patients with peripheral artery disease: results from U.S. Medicare 2000–2008. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(21):2230–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]