Abstract

Cyanobacterial sucrose biosynthesis is stimulated under salt stress, which could be used for biotechnological sugar production. It has been shown that the response regulator Slr1588 negatively regulates the spsA gene encoding sucrose-phosphate synthase and mutation of the slr1588 gene also affected the salt tolerance of Synechocystis (Chen et al., 2014). The latter finding is contrary to earlier observations (Hagemann et al., 1997b). Here, we observed that ectopic expression of slr1588 did not restore the salt tolerance of the slr1588 mutant, making the essential function of this response regulator for salt tolerance questionable. Subsequent experiments showed that deletion of the entire coding sequence of slr1588 compromised the expression of the downstream situated ggpP gene, which encodes glucosylglycerol-phosphate phosphatase for synthesis of the primary osmolyte glucosylglycerol. Mutation of slr1588 by deleting the N-terminal part of this protein (Δslr1588-F976) did not affect ggpP expression, glucosylglycerol accumulation as well as salt tolerance, while the mutation of ggpP resulted in the previously reported salt-sensitive phenotype. In the Δslr1588-F976 mutant spsA was up-regulated but sucrose content was lowered due to increased invertase activity. Our results reveal that Slr1588 is acting as a repressor for spsA as previously suggested but it is not crucial for the overall salt acclimation of Synechocystis.

Keywords: slr1588, Synechocystis, spsA, glucosylglycerol, sucrose, ggpP, response regulator, transcriptional regulation

Introduction

Increasing concerns about growing human populations, resource use and proposed climate change scenarios promoted the development of sustainable methods for biomass and energy production. One approach aims to use microalgae and cyanobacteria as green cell factories for the production of valuable products. Genetic engineering of cyanobacteria was well established and allowed the generation of strains producing various biofuels (Kopka et al., 2017). Carbohydrates such as sucrose are also interesting products (Hays and Ducat, 2015), since they can be directly used for human nutrition or for feeding heterotrophic bacteria in biotechnological co-cultivation approaches (Ducat et al., 2012). Metabolic engineering approaches combining overexpression of sucrose synthesis enzymes and heterologous sucrose exporters generated cyanobacterial strains that showed great potentials in sucrose production (Ducat et al., 2012; Song et al., 2016).

Naturally, cyanobacterial sucrose accumulation is part of their acclimation to high salt concentrations. To cope with salt stress, cyanobacteria developed two main strategies: actively exporting inorganic ions (e.g., Na+) and accumulating organic osmolytes such as sucrose, trehalose, glucosylglycerol (GG), glycine betaine (Hagemann, 2011) or homoserine betaine (Pade et al., 2016). A high body of research on salt acclimation and the biosynthesis of osmolytes was performed using the model cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (hereafter Syn6803). In Syn6803, sucrose is transiently accumulated as secondary osmolyte additionally to the primary osmolyte GG (Reed and Stewart, 1985; Marin et al., 2004). As in plants, sucrose is synthesized from UDP-glucose and fructose 6-phosphate by a two-step pathway consisting of sucrose-phosphate synthase (encoded by spsA) (Hagemann and Marin, 1999) and sucrose-phosphate phosphatase (encoded by spp) among cyanobacteria (Lunn, 2002; Fieulaine et al., 2005). Invertase encoded by invA is responsible for sucrose degradation (Vargas et al., 2003). In our previous work, we found that spsA overexpression leads to a threefold increase in sucrose accumulation of Syn6803 under salt-stress conditions. This finding provided evidence that SpsA catalyzes the limiting step of sucrose accumulation (Du et al., 2013). The spsA gene of Syn6803 was found to be induced after salt shock and sucrose was mainly accumulated at the early stage of salt acclimation (Desplats et al., 2005). However, regulatory mechanisms and signal transduction pathways for both, spsA transcription and sucrose biosynthesis, are not well understood among cyanobacteria.

Two-component signal transduction systems, which typically consist of a sensory histidine kinase (Hik) and a response regulator (Rre), play important roles in responding to stresses in many microorganisms (Stock et al., 1989). By screening a library of 43 Hik mutants using DNA microarray analysis, four Hiks, namely Hik16, Hik33, Hik34, and Hik41, were identified to perceive and transduce the salt signal. These Hiks regulated approximately 20% of the salt-inducible genes (Marin et al., 2003). Subsequently, some Hik-Rre pairs were identified to be involved in perception of salt stress and signal transduction (Shoumskaya et al., 2005). However, these studies did not provide evidence that Hik-Rre systems directly regulate the spsA transcription in Syn6803 under salt stress. The gene slr1588 that encodes an orphan Rre of Syn6803 (Rre39) was reported to directly regulate accumulation of salt-stress proteins including SpsA (Chen et al., 2014). These authors showed that the spsA gene was highly expressed at both, RNA and protein levels, under salt-stress condition after complete deletion of slr1588. They also conducted electrophoretic mobility shift assays showing that the recombinant Slr1588 protein bound directly to the upstream region of spsA gene in vitro. Consistent with the regulatory role of Slr1588 on many salt-regulated proteins, the slr1588-null mutant showed a salt-sensitive phenotype, i.e., it could not grow in media supplemented with 4% of NaCl (Chen et al., 2014). However, this finding is inconsistent with an earlier report (Hagemann et al., 1997b), in which the slr1588 mutant did not show changed salt resistance. Interestingly, the slr1588 gene is situated upstream of two other genes with important functions in salt acclimation of Syn6803. The first downstream gene slr0746 (ggpP) encodes the GG-phosphate phosphatase catalyzing the second step in GG synthesis (Hagemann et al., 1997b), whereas the second gene slr0747 (ggtA) encodes the ATP-binding subunit of the ABC-transporter for GG, trehalose, and sucrose (Hagemann et al., 1997a). It has been reported that the ggpP mutant of Syn6803 is sensitive to salt stress (Hagemann et al., 1997b), whereas the ggtA mutant grew like wild type (WT) in NaCl-supplemented BG11 medium (Hagemann et al., 1997a).

Due to the inconsistency in previous reports on the role of the Rre Slr1588 in salt acclimation of Syn6803, we re-evaluated its functions using a set of newly generated mutants including complementation of the slr1588-null mutant. The salt tolerances, osmolyte accumulation and expression levels of selected genes were analyzed in these strains under salt-stress conditions. These experiments revealed the actual role of Slr1588 in spsA expression regulation but not in salt tolerance of Syn6803.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

Chemicals were obtained from the Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Company (China). Taq and Pfu DNA polymerases were purchased from Transgen Biotech (China). Restriction endonucleases were purchased from ThermoFisher (United States). The kits used for molecular cloning were purchased from Omega (United States). GG standard was obtained from the Bitop company (Germany).

Plasmids and Strains Construction

A modified fusion polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method was employed for the construction of gene knockout constructs (Wang et al., 2002). Briefly, for gene targeting, we used three sets of primers (Supplementary Table S3) to amplify a kanamycin resistance cassette from pET28a (Novagen) and two arms of the targeted genes from the genome of Syn6803. The three DNA fragments were denatured, annealed, and extended. The resulting mixture was subsequently amplified with a set of nested primers (Supplementary Table S3). Then, the fused PCR fragment was ligated into pEasy-Blunt vector (TransGen Biotech, China). The resulting plasmids (Supplementary Table S2) were used for transforming the WT strain (glucose-tolerant) of Syn6803 for gene targeting.

To generate plasmids used for complementation of the slr1588 mutant, restriction sites of NdeI and XhoI were added to the ends of slr1588 ORF by PCR (Supplementary Table S3). The PCR products were cut by NdeI and XhoI and ligated into the pXT37b (Tan et al., 2011), which was cut with the same enzymes, resulting in plasmid pSK005. The PcpcB promoter fragment was cut from pXX47 (Zhu et al., 2015) using KpnI/NdeI, and ligated into the same sites of pSK005, resulting in pSK008. The gene slr1588 including 230 bp upstream region, which is supposed to contain its native promoter, was amplified using primers pSK013-1 and pSK013-2 (Supplementary Table S3) and ligated into the KpnI/XhoI sites of pXT37b, resulting in pSK013. These three plasmids were used for transforming the slr1588 mutant.

Transformation of Synechocystis

Natural transformation of Syn6803 was performed according to published procedures (Williams, 1988). Briefly, 1 mL of exponentially growing cells was harvested. The cells were washed twice with fresh BG-11 (Rippka et al., 1979) medium. A 400 μL aliquot of cultures at a density of 1 × 109 cells mL-1 was mixed with plasmid DNA at a final DNA concentration of 10 μg mL-1. After incubation under illumination of approximately 50 μmol photons m-2 s-1 at 30°C for 5 h, the cell suspension was spread onto membrane filters resting on BG11 agar plates (without antibiotic) for 1 day. The filters were then placed on fresh BG11 agar plates containing antibiotics at the appropriate concentrations. After 1–2 weeks of incubation at 30°C under illumination of approximately 50 μmol photons m-2 s-1, single colonies were streaked onto antibiotic-containing agar plates. Subsequently, selected clones were grown in liquid BG11 medium supplemented with antibiotics. The complete segregation of the mutant genotypes was confirmed by PCR and sequence analysis. The confirmed Syn6803 mutants were used for further analysis. Mutant strains and related genotypes are listed in Supplementary Table S1, plasmids and its functions are listed in Supplementary Table S2, while PCR primers used for mutant construction and validation are listed in Supplementary Table S3.

Cultivation and Salt Shock of Synechocystis Strains

The cyanobacteria were routinely cultivated on BG11 plates with appropriate antibiotics (20 and 30 μg mL-1 for spectinomycin and kanamycin, respectively), at 30°C, under illumination of approximately 50 μmol photons m-2 s-1. For evaluation of salt tolerances of Syn6803 strains, they were inoculated at an initial OD730 of ∼0.05 in 50 mL flasks, containing 20 mL fresh BG11 medium supplemented with 4% (684 mM) NaCl and appropriate antibiotics. The cells were cultivated at 30°C with shaking (150 rpm) and constant white light illumination (50 μmol photons m-2 s-1). The growth was monitored by measuring the optical density (OD) at 730 nm.

For detection of osmolyte contents and mRNA levels, Syn6803 cells were grown in column photo bioreactors (Tan et al., 2015) at 30°C with 5% CO2-air (v/v) aeration, and constant light illumination (100 μmol photons m-2 s-1) to the late exponential phase. Then, an aliquot BG11 supplemented with NaCl (5 M) was added to reach a final NaCl concentration of 684 mM (4%).

RNA Isolation, Reverse Transcription PCR and Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

Cells from 4 mL cultures with an OD730 of ∼5 were collected. Total RNA was isolated from cells using MiniBEST Universal RNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa, Japan). The absence of genomic DNA from RNA preparations was verified by PCR using primer set rnpb-1 and rnpb-2 (Supplementary Table S4). Reverse transcription was done using PrimeScriptTM RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Japan). Aliquots of the generated cDNA were used for the reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) assays. Quantitative Real-Time PCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM II (TaKaRa) in a Light Cycler 480 (Roche). The primers shown in Supplementary Table S4 were used for real-time PCR.

Determination of Intracellular Osmolytes in Synechocystis Cells

Cells from 2 ml aliquots of cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 5 min. The pretreatment method was designed according to our previous report (Du et al., 2013). Briefly, cells were suspended in 1 mL of 80% ethanol (v/v) and then incubated at 65°C for 4 h. After centrifugation at 12,000 ×g for 5 min, the supernatants were transferred into a clean tube and then dried under a stream of N2 at 55°C. The dry residues were dissolved in ultrapure water, subjected to membrane filtration (0.22 μm), and analyzed by ion chromatography ICS-5000 (Dionex, United States). The ion chromatography system was equipped with an electrochemical cell (Dionex, United States) and a Carb-PacsTM MA1 analytical column (4 mm × 250 mm). The column was equilibrated with 800 mM NaOH at a flow rate of 0.4 mL min-1.

Enzymatic Activity Assay for Invertase

Sucrose degradation activity was determined according to the previously reported method (Vargas et al., 2003) with modifications. Reaction mixtures containing 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 2 g L-1 sucrose and an appropriate volume of enzyme in a final volume of 50 μL were prepared. Mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 1.5 h. The amount of glucose was measured using ion chromatography. Proteins were quantified according to Bradford (Bradford, 1976).

Results

Reconstruction and Complementation of the slr1588-Null Mutant

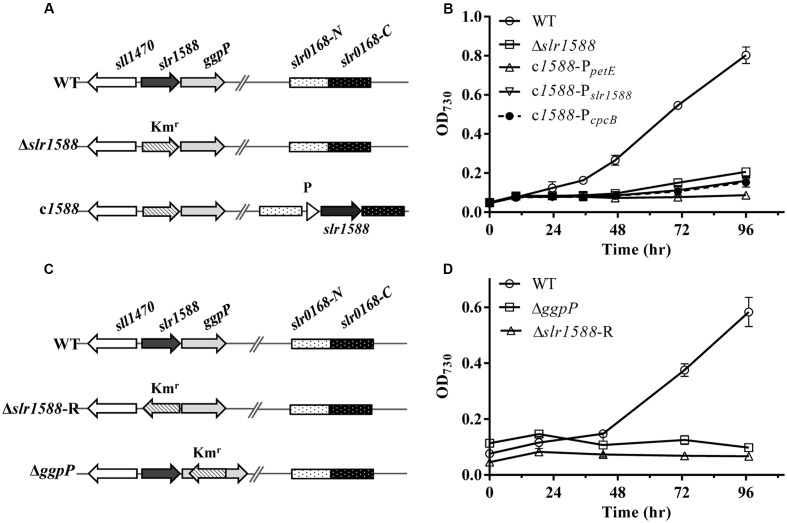

Mutants of slr1588 showed different salt tolerance levels in previous reports (Hagemann et al., 1997b; Chen et al., 2014). To clarify whether or not the inactivation of Slr1588 was directly responsible for the salt-sensitive phenotype of the corresponding mutant of Syn6803, we initially constructed slr1588 complementation strains in the slr1588-null mutant background. For this purpose, the slr1588-null mutant (Δslr1588) was newly generated by replacing the complete coding sequence of slr1588 with a kanamycin resistance cassette (Figure 1A), exactly as has been done in the previous study (Chen et al., 2014). Then, slr1588 was ectopically expressed under control of three different promoters namely PpetE (Tan et al., 2011), PcpcB (Zhou et al., 2014), or Pslr1588, at a neutral site in the genome of the Δslr1588 mutant (Figure 1A).

FIGURE 1.

The genomic structures and growth of different strains of Syn6803 under salt-stress condition. (A) Schematic representation of the slr1588 and the slr0168 loci in different strains. In the Δslr1588 mutant, the complete coding region of slr1588 was replaced by a kanamycin resistance cassette (Kmr). In the complementation strains, DNA fragments expressing the slr1588 gene under control of three different promoters (P: PpetE, PcpcB or Pslr1588) were inserted into the neutral slr0168 locus of the Δslr1588 mutant. (B) All five strains were grown in BG11 media containing 4% NaCl. Growth was monitored by measuring OD730. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3). (C) In comparison to the initial Δslr1588 mutant, the Kmr fragment was inserted with reverse orientation in mutant Δslr1588-R. The Kmr fragment replaced parts of the coding sequence in the ΔggpP mutant. (D) All strains were grown in BG11 media containing 4% NaCl, and monitored by measuring OD730. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3).

The salt tolerance of the resulting strains was compared with the WT of Syn6803. The Δslr1588 mutant as well as all three complemented strains showed salt-sensitive phenotypes, i.e., they could not grow in the presence of 4% NaCl. These results indicate that the salt-sensitive phenotype of the Δslr1588 mutant is not directly related to the Slr1588 inactivation. Probably, there exists an additional mutation in Δslr1588 leading to its salt sensitivity as reported by Chen et al. (2014).

Deletion of the Complete Coding Sequence of slr1588 Disturbs the ggpP Expression

The disruption of the downstream situated gene ggpP resulted in salt sensitivity of Syn6803 (Hagemann et al., 1997b), suggesting that polar effects of complete slr1588 deletion on the expression of ggpP could be responsible for the salt sensitivity of the mutant Δslr1588.

To prove this assumption, we first generated new mutants of Syn6803. Consistent with the previously reported ggpP mutant (Hagemann et al., 1997b), our newly generated ΔggpP mutant, in which the kanamycin resistance cassette was inserted in reverse orientation into the ggpP gene (Figure 1C), showed the expected salt-sensitive phenotype (Figure 1D). Similarly, the newly generated Δslr1588-R mutant, in which the kanamycin resistance gene was also inserted in opposite transcriptional orientation relative to slr1588, showed again the salt-sensitive phenotype (Figures 1C,D). Thus, the ggpP deletion resulted in the same salt-sensitive phenotype as the complete slr1588 deletion.

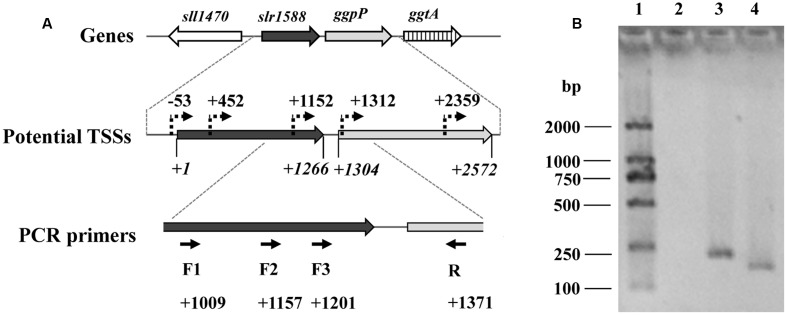

We assumed that the slr1588 mutation might somehow affect the ggpP expression. These two genes are only separated by 39 bp (Kaneko et al., 1996), but separately expressed. Recent dRNA-seq analyses (Kopf et al., 2014) mapped all transcriptional start sites (TSSs) in Syn6803. This study showed that three potential TSSs exist for ggpP transcription, two of them are located inside the slr1588 coding sequence, namely at positions 452 and 1152, respectively (Figure 2A). To verify these TSSs of ggpP, we aimed to amplify DNA fragments overlapping slr1588 and ggpP from cDNA of the WT strain grown under salt-stress condition. As shown in Figure 2B, these experiments verified the ggpP TSS at position 1152 inside slr1588, since PCR bands of the expected sizes were amplified using the primer pairs F2/R and F3/R but not with the primer pair F1/R. As positive controls, the expected bands could be obtained from genomic DNA of Syn6803 using these primer pairs (Supplementary Figure S1). These results suggest that the transcripts of ggpP indeed overlapped with slr1588. However, the second intragenic TSS for ggpP at position 452 inside of slr1588 could not be found here, possibly, it is not active under salt-stress conditions.

FIGURE 2.

Analysis of the ggpP transcription by RT-PCR. (A). The potential TSSs of ggpP inside slr1588 predicted by dRNA-seq (Kopf et al., 2014) were labeled as dotted arrows. The translation start site of slr1588 was set as +1, and the relative locations of these TSSs inside the ORF of slr1588 or ggpP were calculated. For RT-PCR, three forward primers (F1, 2 and 3, binding sites inside slr1588 are indicated) specific to slr1588 and a reverse primer (R) specific to ggpP were designed. (B). Separation of DNA-fragments obtained by RT-PCR using cDNA of salt-grown cells of the wild type (WT) strain as template. Lane 1: a DNA ladder; Lane 2, 3 and 4: three primer pairs (F1/R, F2/R, and F3/R) were used for amplification, respectively.

Generation of slr1588 Mutants Not Affecting ggpP Expression

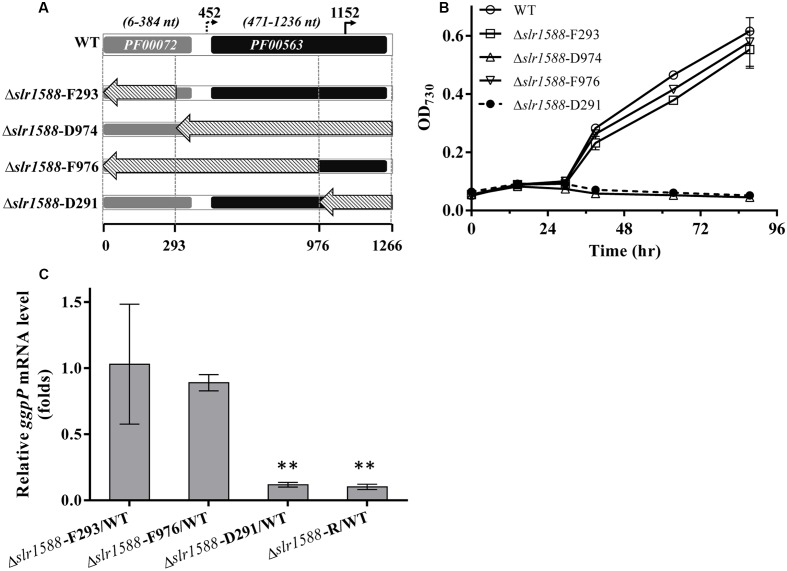

The above-described results make it likely that the deletion of the entire coding region of slr1588 in the mutants Δslr1588 and Δslr1588-R abolished ggpP expression leading to the salt-sensitive phenotype. Therefore, we aimed to obtain slr1588 inactivation not interfering with ggpP transcription. To this end, we constructed four new slr1588 mutants taking into consideration the domain structure of Slr1588 and the locations of the intragenic TSS of ggpP (Figure 3). According to the InterPro database, the Slr1588 protein consists of two domains, a receiving (pfam: 00072) and an EAL (pfam: 00563) domain. As shown in Figure 3A, these two domains are encoded in the sequence of slr1588 from positions 6 to 384 and from positions 471 to 1236, respectively. These parts of the gene were separately deleted in the mutants Δslr1588-F293 and Δslr1588-D974, respectively. The two potential intragenic TSSs are located at positions 452 and 1152 of slr1588. Although we showed that the former TSS was inactive under salt-stress conditions, it might be important under other conditions. Based on these considerations, two additional mutants, Δslr1588-F976 and Δslr1588-D291 were generated, in which specific parts of the slr1588 coding region were deleted but leaving the first or the second potential TSS of ggpP intact (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Salt tolerance and transcript levels of the ggpP gene in cells of mutants with partly deleted slr1588. (A) DNA fragments from positions 1 to 293, 294 to 1266, 1 to 976, and 977 to 1266 of slr1588 coding sequence were replaced by the Kmr fragment resulting in the Δslr1588-F293, D974, F976, and D291 mutants, respectively. (B) Growth curves of the four partly deleted slr1588 mutants and the WT strain in BG11 supplemented with 4% NaCl. (C) ggpP transcript levels relative to WT cells in three slr1588 mutants grown in BG11 supplemented with 4% NaCl for 24 h. The stars (∗∗) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

The salt tolerance of these four slr1588 mutants was compared to WT Syn6803 grown in BG11 medium supplemented with 4% NaCl. Similar to the complete deletion mutant Δslr1588-R, the Δslr1588-D974 and Δslr1588-D291 mutants showed no growth at high salt concentrations (Figure 3B). In all these three salt-sensitive mutants, the last 291 nts of the slr1588 ORF including the second intragenic TSS of ggpP were deleted. In contrast, the Δslr1588-F293 and the Δslr1588-F976 mutants, where parts of coding sequence of slr1588 and the first intragenic TSS of ggpP were deleted but the second TSS remained intact, showed the same salt tolerance as WT cells (Figure 3B).

The above-described results clearly indicate that not the absence of Slr1588 but the interference with ggpP expression is responsible for the salt sensitivity among these mutants. This conclusion was supported by qPCR analyses of ggpP in selected mutant strains under salt-stress conditions. As expected from the defined deletions, the ggpP transcription was significantly decreased in the Δslr1588-D291 mutant, where the 3′ part of slr1588 including the ggpP TSS at position 1152 was deleted. The ggpP mRNA content was ∼90% lower than in WT cells 24 h after salt shock (Figure 3C), similar to the level found in the Δslr1588-R mutant (Figure 3C and Table 1). However, the ggpP transcript levels remained unchanged compared to WT in the two other mutants Δslr1588-F293 and Δslr1588-F976, where the TSS for ggpP at 3′ end of slr1588 remained intact but 5′ parts of slr1588 were deleted (Figure 3C). These results clearly support the notion that not the mutation of slr1588 but the abolished ggpP transcription was responsible for salt-sensitive phenotype.

Table 1.

Effects of gene deletion on transcript levels of genes encoding proteins involved in sucrose or glucosylglycerol (GG) metabolism.

| Genes | Annotation | Δslr1588-R/WT (folds)a,b | ΔggpP/WT (folds)a,b | Δslr1588-F976/WT (folds)a,b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| spsA | Sucrose-phosphate synthase | 1.863 ± 0.138∗ | 0.590 ± 0.031∗ | 1.747 ± 0.269∗ |

| spp | Sucrose-phosphate phosphatase | 5.965 ± 0.574∗ | 1.100 ± 0.042 | 1.298 ± 0.181 |

| ggpS | Glucosylglycerol-phosphate synthase | 2.037 ± 0.352 | 1.871 ± 0.043∗ | 0.814 ± 0.098 |

| ggpP | Glucosylglycerol-phosphate phosphatase | 0.102 ± 0.016∗ | ND | 0.890 ± 0.050 |

| invA | Putative neutral invertase | 0.388 ± 0.019∗ | 0.137 ± 0.021∗ | 1.106 ± 0.226 |

| slr1588 | Response regulator | ND | 1.056 ± 0.257 | ND |

aData are shown as means ± SD (n = 3).

bND, Not determined.

∗Stars represent significant differences (p < 0.05) of gene transcription levels between the wild type (WT) and the mutant strains.

Effects of Specific Deletions of slr1588 and ggpP on Gene Expression

In addition to salt tolerance, the Slr1588 protein was shown to be involved in the expression regulation of several genes encoding proteins involved of salt tolerance in Syn6803 (Chen et al., 2014). Using defined mutants with defects in either slr1588 or ggpP, we aimed to investigate the role of these proteins in gene expression regulation under salt-stress conditions. Thus, the single gene mutants Δslr1588-F976 and ΔggpP were compared with the Δslr1588-R mutant (complete slr1588 deletion and abolished ggpP expression) as well as WT of Syn6803 regarding the transcript levels of spsA, spp, and ggpS in 24 h after salt shock (4% NaCl). As shown in the previous study (Chen et al., 2014), the mRNA levels of spsA and ggpS were significantly elevated in the Δslr1588-R mutant (Table 1). However, the transcription levels of both, ggpS and spp, remained at WT levels in the Δslr1588-F976 mutant (Table 1). Moreover, the expression level of ggpS was also similar in the mutants Δslr1588-R and ΔggpP. Only the gene spsA was significantly up-regulated in the Δslr1588-F976 mutant (Table 1). These findings verify a specific role of Slr1588 as a negative regulator of spsA transcription under salt-stress condition in Syn6803 as proposed by Chen et al. (2014), whereas the other transcriptional changes seem to be rather the result of the salt-sensitivity due to abolished ggpP expression in the Δslr1588-R mutant.

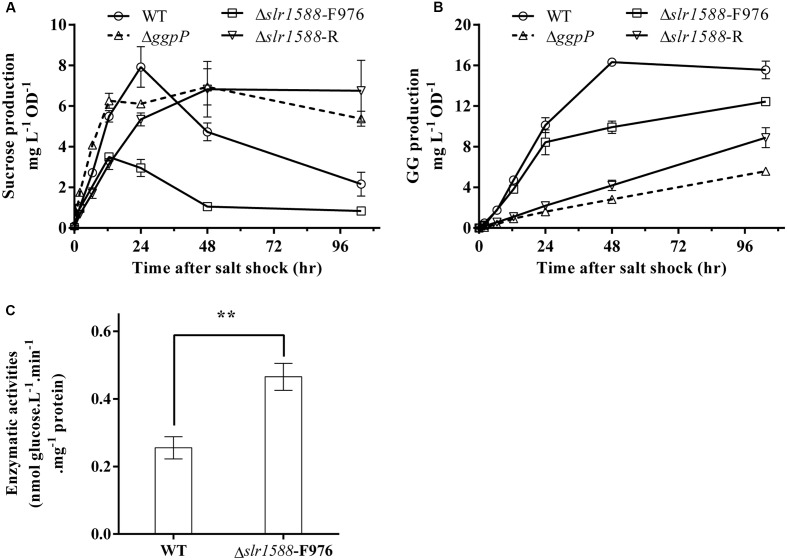

Specific Role of slr1588 on Osmolyte Accumulation in Syn6803

Finally, we aimed to analyze whether or not the mutation of the Rre Slr1588 had specific effects on the amounts of sucrose and GG serving as main osmolytes in salt-stressed cells of Syn6803 (Reed and Stewart, 1985). To this end, the mutants Δslr1588-F976, Δslr1588-R, ΔggpP, as well as the WT were exposed to 4% NaCl up to 96 h. Sucrose contents increased to the peak level in first 24 h after salt shock. Subsequently, it decreased to only slightly elevated levels during the following 36 h. During this period, sucrose was replaced by GG that reached its maximum amount at about 48 h (Figures 4A,B). In the mutants Δslr1588-R and ΔggpP with impaired ggpP transcription, GG accumulation was strongly inhibited, whereas sucrose contents were kept unchanged after reaching their peak level (Figures 4A,B). These findings suggest that cells try to compensate for the decreased GG accumulation by enhanced sucrose accumulation as shown before for several mutants affected in GG synthesis (Marin et al., 1998). Surprisingly, we found only 44% of the sucrose content of WT cells in the Δslr1588-F976 mutant despite the significantly enhanced spsA expression. GG accumulation rate was also slightly lower in this mutant compared to WT (Figures 4A,B). These findings indicate that the specific inactivation of Slr1588 without disrupting ggpP transcription leads to decreased osmolyte accumulation.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of the slr1588 inactivation on osmolyte contents and invertase. Cultures at late exponential phase of different strains were shifted to 4% of NaCl. Sucrose (A) and glucosylglycerol (GG) (B) contents were measured. (C) The invertase activity in the Δslr1588-F976 was compared with that of WT in cells grown at 4% NaCl for 24 h. ∗∗Stars represent significant differences (p < 0.05) of enzymatic activities between the wild type (WT) and the Δslr1588-F976 mutant strain.

Post-transcriptional regulation of SpsA or stimulated sucrose breakdown by invertase are possible explanations for decreased sucrose amounts in mutant Δslr1588-F976 despite stimulated spsA transcript amounts. To this end, we analyzed expression and activity of invertase, which is responsible for sucrose breakdown (Vargas et al., 2003). We did not find significant difference in the invA transcription between the WT and the Δslr1588-F976 mutant under salt-stress conditions (Table 1), whereas invA expression was significantly reduced in the mutants ΔggpP and Δslr1588-R. However, the invertase activity in crude extracts of the mutant Δslr1588-F976 was significantly higher than that in the WT (Figure 4C). This result partially explains why sucrose levels decreased after inactivation of Slr1588 in the presence of elevated spsA transcription.

Discussion

Cyanobacterial acclimation to varying salt concentrations is well understood on the physiological and molecular level (Hagemann, 2011), but its sensing and signal transduction is only fragmentary known. Two-component systems are often involved in the response of bacteria to environmental factors. However, the systematic screening of Hik and Rre of Syn6803 did not identify a system regulating osmolyte accumulation or overall salt tolerance (Marin et al., 2004; Shoumskaya et al., 2005). Similarly, the mutation of the Rre orrA abolished the salt-regulation of target genes without lowering the general salt or osmotic stress tolerance of Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 (Schwartz et al., 1998). Interestingly, Chen et al. (2014) reported that mutation of the Rre gene slr1588 resulted in increased abundances of many salt-induced genes/proteins and was accompanied by a clear salt-sensitive phenotype. The latter finding is contrasting earlier findings, which reported unchanged salt tolerance of this mutant (Hagemann et al., 1997b). It is possible that differences in phenotypes could be owing to genome differences in laboratory strains of Syn6803 (Ikeuchi and Tabata, 2001; Trautmann et al., 2012). However, observed sequence differences are rather low. And despite glucose utilization or changed motility, no clear phenotypic differences have been assigned to the genome sequence differences in these laboratory strain derivatives (Tajima et al., 2011). Thus, we assumed that possible polar effects of the different mutations could be responsible for these phenotypic differences, since the previous studies (Hagemann et al., 1997b; Chen et al., 2014) used different strategies for the slr1588 knockout. Furthermore, these studies did not provide final proof of the linkage of mutation and phenotype by complementation approaches.

The Salt-Sensitive Phenotype Is Linked to Abolished Expression of ggpP But Not of slr1588 Mutation

To rule out strain differences, a new set of mutants were generated in the same WT background, i.e., the glucose-tolerant version of Syn6803. Initial complementation of the salt-sensitive phenotype by ectopic expression of slr1588 in the newly generated deletion mutants Δslr1588 and Δslr1588-R failed, i.e., these strain were still unable to grow at 4% NaCl (Figure 1B). Hence, polar effects of this mutation on other genes became likely, particularly on the downstream situated ggpP gene, whose mutation was linked with salt sensitivity (Hagemann et al., 1997b). Careful inspection of TSSs of ggpP provided by Kopf et al. (2014) and its experimental verification (Figure 2) indicated that the deletion of the complete slr1588 also affected ggpP expression. This hypothesis was verified using mutants with only partial deletions of slr1588. For example, the deletion of the last 291 bp of slr1588 resulted in a ∼90% decrease in ggpP transcription (Table 1 and Figure 3C) linked with the expected salt sensitivity of these strains (Figures 1B,D, 3B). These findings revealed that deletions of the 3′ part of slr1588 also removed the promoter and the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) of the downstream gene ggpP, thereby decreasing its expression as well as the salt tolerance of Syn6803.

Role of Slr1588 on Transcription of spsA, ggpS, and ggpP

Chen et al. (2014) provided evidence that the changed expression of at least some salt-regulated genes resulted from direct binding of Slr1588 to the corresponding promoter regions. They showed a spsA upregulation, which was verified here using the newly generated Δslr1588-F976 mutant, which is characterized by a partial deletion of slr1588 leaving ggpP expression intact (Figure 3C). These findings support the notion of the previous report (Chen et al., 2014) that Slr1588 serves as a negative regulator for the spsA transcription.

However, the reported role of Slr1588 as a repressor of ggpS (Chen et al., 2014) could not be verified here. Consistent with the previous work we showed that the ggpS mRNA levels significantly increased in the complete slr1588-deletion mutant (Table 1). However, this alteration is clearly caused by the impaired ggpP transcription in this mutant, because ggpS transcription was increased by similar ratios in both, the Δslr1588-R and ΔggpP mutants (Table 1). In contrast, ggpS transcription was not affected in the Δslr1588-F976 mutant, where ggpP transcription remained comparable to that of the WT strain (Figure 3C). Therefore, the single mutation of Slr1588 had no regulatory effect on the ggpS transcription of Syn6803 in vivo despite its binding to the ggpS promoter region in vitro as shown by Chen et al. (2014). Different potential regulators for ggpS have been identified in the last years. First, the small upstream-encoded protein GgpR was found to act as a repressor for ggpS, since its mutation resulted in enhanced ggpS expression (Klähn et al., 2010). Recently, the transcriptional factor LexA was identified to regulate many genes in Syn6803, among them it is also negatively affecting ggpS expression under low salt conditions (Klähn et al., 2010; Kizawa et al., 2016). Obviously, the ggpS gene is subject to a complex regulation involving different regulatory proteins of unknown hierarchical order. At least in vivo, the absence of Slr1588 was compensated by the other regulators leading to ggpS expression similar to WT.

Role of Slr1588 on Accumulation of Sucrose and GG

Finally, we were interested to know whether expression changes of osmolyte genes correlate with product levels in the different mutant strains. Despite the clear increase of spsA transcript level, rather decreased sucrose amounts were found, when only Slr1588 was inactivated in the Δslr1588-F976 mutant. Our previous report showed that the overexpression of spsA increased sucrose content under salt-stress condition (Du et al., 2013). However, in the Δslr1588-F976 mutant, the inactivation of Slr1588 increased not only the spsA transcription (Table 1) but also the sucrose degradation activities (Figure 4C). The higher invertase activity provided a possible explanation for the decreased sucrose production in the Δslr1588-F976 mutant. In addition, GG accumulation was also lower in cells of this mutant than in WT despite the similar mRNA levels of ggpS in these two strains (Table 1). GG accumulation is primarily controlled by the activity level of GgpS, which depends on contents of inorganic ions inside the cell (Novak et al., 2011). This biochemical regulation also explained that the GG contents remained almost unchanged in the ggpR mutant despite the increased abundance of GgpS (Klähn et al., 2010).

However, whether or not the Slr1588 plays a direct role for the regulation of the invertase activity or in the interplay of sucrose and GG biosynthesis with inorganic ion contents in Syn6803 is not yet known. It is also possible that the primary osmolyte in Syn6803, GG, plays directly an important role in the regulation of salt tolerance processes. When GG biosynthesis was impaired by inhibiting the ggpP transcription, both the Δslr1588-R and the ΔggpP mutants showed increased sucrose levels to compensate for the absence of GG (Figures 4A,B) as has been reported before for the ggpS mutant (Marin et al., 1998). Considering the increased transcript levels of ggpS, spsA, and spp and the decreased invA levels in the ΔggpP mutant (Table 1), it can be assumed that unbalanced GG and sucrose levels could lead to insufficient turgor pressure control, which may act as signals for the transcriptional as well as activity regulation of the involved genes/proteins. Future work is necessary to unravel the salt-sensing network and the specific function of the assigned transcriptional regulators such as GgpR, Slr1588, and LexA.

Author Contributions

KS performed experiments, analyzed data and drafted the manuscript. XT designed the researches, analyzed data and drafted the manuscript. XL and MH analyzed data and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Weiwen Zhang and Dr. Lei Chen for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (31525002 to XL), the Joint Sino-German Research Project (grant GZ 984 to XL and MH), the Shandong Taishan Scholarship (XL), the National Science Foundation of China (31301018 to XT), and the Key Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (ZDRW-ZS-2016-3 to XT).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01176/full#supplementary-material

References

- Bradford M. M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72 248–254. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Wu L., Zhu Y., Song Z., Wang J., Zhang W. (2014). An orphan two-component response regulator Slr1588 involves salt tolerance by directly regulating synthesis of compatible solutes in photosynthetic Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Mol. Biosyst. 10 1765–1774. 10.1039/c4mb00095a00095a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desplats P., Folco E., Salerno G. L. (2005). Sucrose may play an additional role to that of an osmolyte in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 salt-shocked cells. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 43 133–138. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2005.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W., Liang F., Duan Y., Tan X., Lu X. (2013). Exploring the photosynthetic production capacity of sucrose by cyanobacteria. Metab. Eng. 19 17–25. 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducat D. C., Avelar-Rivas J. A., Way J. C., Silver P. A. (2012). Rerouting carbon flux to enhance photosynthetic productivity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 2660–2668. 10.1128/aem.07901-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieulaine S., Lunn J. E., Borel F., Ferrer J.-L. (2005). The structure of a cyanobacterial sucrose-phosphatase reveals the sugar tongs that release free sucrose in the cell. Plant Cell Online 17 2049–2058. 10.1105/tpc.105.031229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann M. (2011). Molecular biology of cyanobacterial salt acclimation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35 87–123. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00234.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann M., Marin K. (1999). Salt-induced sucrose accumulation is mediated by sucrose-phosphate-synthase in cyanobacteria. J. Plant Physiol. 155 424–430. 10.1016/S0176-1617(99)80126-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann M., Richter S., Mikkat S. (1997a). The ggtA gene encodes a subunit of the transport system for the osmoprotective compound glucosylglycerol in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 179 714–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann M., Schoor A., Jeanjean R., Zuther E., Joset F. (1997b). The stpA gene form synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 encodes the glucosylglycerol-phosphate phosphatase involved in cyanobacterial osmotic response to salt shock. J. Bacteriol. 179 1727–1733. 10.1128/jb.179.5.1727-1733.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays S. G., Ducat D. C. (2015). Engineering cyanobacteria as photosynthetic feedstock factories. Photosynth. Res. 123 285–295. 10.1007/s11120-014-9980-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi M., Tabata S. (2001). Synechocystis sp PCC 6803 - a useful tool in the study of the genetics of cyanobacteria. Photosynth. Res. 70 73–83. 10.1023/A:1013887908680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T., Sato S., Kotani H., Tanaka A., Asamizu E., Nakamura Y., et al. (1996). Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 3 109–136. 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizawa A., Kawahara A., Takimura Y., Nishiyama Y., Hihara Y. (2016). RNA-seq profiling reveals novel target genes of LexA in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Front. Microbiol. 7:193 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klähn S., Hohne A., Simon E., Hagemann M. (2010). The gene ssl3076 encodes a protein mediating the salt-induced expression of ggpS for the biosynthesis of the compatible solute glucosylglycerol in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 192 4403–4412. 10.1128/JB.00481-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopf M., Klahn S., Scholz I., Matthiessen J. K., Hess W. R., Voss B. (2014). Comparative analysis of the primary transcriptome of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. DNA Res. 21 527–539. 10.1093/dnares/dsu018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopka J., Schmidt S., Dethloff F., Pade N., Berendt S., Schottkowski M., et al. (2017). Systems analysis of ethanol production in the genetically engineered cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Biotechnol. Biofuels 10 56 10.1186/s13068-017-0741-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn J. E. (2002). Evolution of sucrose synthesis. Plant Physiol. 128 1490–1500. 10.1104/pp.010898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin K., Kanesaki Y., Los D. A., Murata N., Suzuki I., Hagemann M. (2004). Gene expression profiling reflects physiological processes in salt acclimation of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Plant Physiol. 136 3290–3300. 10.1104/pp.104.045047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin K., Suzuki I., Yamaguchi K., Ribbeck K., Yamamoto H., Kanesaki Y., et al. (2003). Identification of histidine kinases that act as sensors in the perception of salt stress in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 9061–9066. 10.1073/pnas.1532302100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin K., Zuther E., Kerstan T., Kunert A., Hagemann M. (1998). The ggpS gene from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 encoding glucosyl-glycerol-phosphate synthase is involved in osmolyte synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 180 4843–4849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak J. F., Stirnberg M., Roenneke B., Marin K. (2011). A novel mechanism of osmosensing, a salt-dependent protein-nucleic acid interaction in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis species PCC 6803. J. Biol. Chem. 286 3235–3241. 10.1074/jbc.M110.157032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pade N., Michalik D., Ruth W., Belkin N., Hess W. R., Berman-Frank I., et al. (2016). Trimethylated homoserine functions as the major compatible solute in the globally significant oceanic cyanobacterium Trichodesmium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 13191–13196. 10.1073/pnas.1611666113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed R. H., Stewart W. D. P. (1985). Osmotic adjustment and organic solute accumulation in unicellular cyanobacteria from freshwater and marine habitats. Mar. Biol. 88 1–9. 10.1007/bf00393037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rippka R., Deruelles J., Waterbury J. B., Herdman M., Stanier R. Y. (1979). Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 111 1–61. 10.1099/00221287-111-1-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S. H., Black T. A., Jager K., Panoff J. M., Wolk C. P. (1998). Regulation of an osmoticum-responsive gene in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 180 6332–6337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoumskaya M. A., Paithoonrangsarid K., Kanesaki Y., Los D. A., Zinchenko V. V., Tanticharoen M., et al. (2005). Identical Hik-Rre systems are involved in perception and transduction of salt signals and hyperosmotic signals but regulate the expression of individual genes to different extents in Synechocystis. J. Biol. Chem. 280 21531–21538. 10.1074/jbc.M412174200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K., Tan X., Liang Y., Lu X. (2016). The potential of Synechococcus elongatus UTEX 2973 for sugar feedstock production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100 7865–7875. 10.1007/s00253-016-7510-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock J. B., Ninfa A. J., Stock A. M. (1989). Protein phosphorylation and regulation of adaptive responses in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 53 450–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima N., Sato S., Maruyama F., Kaneko T., Sasaki N. V., Kurokawa K., et al. (2011). Genomic structure of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 strain GT-S. DNA Res. 18 393–399. 10.1093/dnares/dsr026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X., Du W., Lu X. (2015). Photosynthetic and extracellular production of glucosylglycerol by genetically engineered and gel-encapsulated cyanobacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99 2147–2154. 10.1007/s00253-014-6273-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X., Yao L., Gao Q., Wang W., Qi F., Lu X. (2011). Photosynthesis driven conversion of carbon dioxide to fatty alcohols and hydrocarbons in cyanobacteria. Metab. Eng. 13 169–176. 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautmann D., Voß B., Wilde A., Al-Babili S., Hess W. R. (2012). Microevolution in cyanobacteria: re-sequencing a motile substrain of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. DNA Res. 19 435–448. 10.1093/dnares/dss024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas W., Cumino A., Salerno G. L. (2003). Cyanobacterial alkaline/neutral invertases. Origin of sucrose hydrolysis in the plant cytosol? Planta 216 951–960. 10.1007/s00425-002-0943-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. L., Postier B. L., Burnap R. L. (2002). Optimization of fusion PCR for in vitro construction of gene knockout fragments. Biotechniques 33 26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. G. K. (1988). Construction of specific mutations in photosystem-II photosynthetic reaction center by genetic-engineering methods in Synechocystis-6803. Methods Enzymol. 167 766–778. 10.1016/0076-6879(88)67088-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Zhang H., Meng H., Zhu Y., Bao G., Zhang Y., et al. (2014). Discovery of a super-strong promoter enables efficient production of heterologous proteins in cyanobacteria. Sci. Rep. 4:4500 10.1038/srep04500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T., Xie X., Li Z., Tan X., Lu X. (2015). Enhancing photosynthetic production of ethylene in genetically engineered Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Green Chem. 17 421–434. 10.1039/c4gc01730g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.