Abstract

Actinomycosis is a common treatable disease caused by Actinomyces, and generally has a good prognosis. However, we report a fatal case of actinomycosis of the nasal cavity. A 54-year-old man, reporting of left nasal obstruction, swelling and sharp pain around the root of the nose, was referred to our hospital. Histopathological examinations led to a definitive diagnosis of actinomycosis, and oral antibiotics were administered in an outpatient setting. However, the patient discontinued follow-up at the outpatient clinic because of the adverse effects of intravenous delivery, and poor compliance with oral antibiotic therapy led to him receiving a less than adequate dose. Thus, in the absence of sufficient antibiotic treatment, necrosis gradually progressed in the lesion, and the patient died of multiple organ failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation caused by local infection.

Background

Actinomycosis is an indolent, progressive infection caused by Actinomyces, which are anaerobic Gram-positive bacteria found in the oral cavity as human oral flora. Although approximately 50% of cases involve the cervicofacial region, actinomycosis arising from the nasal cavity is extremely rare. The prognosis is good in general, and very few cases reported in the literature have resulted in death. Here, however, we report a fatal case of actinomycosis of the nasal cavity in which the infection could not be controlled and sepsis eventually developed.

Case presentation

A 54-year-old man with left nasal obstruction, swelling and sharp pain around the root of the nose, with purulent nasal discharge for 1 month, was referred to our hospital. He had a history of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus and hepatitis C virus infection. The hepatitis C virus infection was stable and did not require treatment.

Endoscopic examinations at presentation showed that the middle and inferior nasal turbinate was covered with necrotic tissue, and the normal structures of the left nasal cavity were almost entirely absent (figure 1). The necrotic tissue had a strong odour. Biopsy from the site of necrosis was difficult because of haemorrhaging and acute pain.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic findings of the left nasal cavity showing necrotic tissue mainly at the inferior turbinate. ※ Nasal septum; ※※ inferior turbinate of the left nasal cavity.

Investigations

Intranasal necrosis requires that differential diagnosis be performed because the necrosis may be caused by malignant tumours, such as carcinoma and lymphoma; a type of collagen disease; and various infectious diseases. To make a definitive diagnosis, physicians must perform serological and histological tests, image assessments and cultivation of bacteria with subsequent assessment.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis at presentation included NK/T cell lymphoma, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, invasive fungal disease, malignant tumour and cocaine inhalation. Laboratory examination showed a mild inflammatory reaction, including a white cell count (WCC) count of 8160/μL and C reactive protein (CRP) level of 3.5 mg/dL, and negative results for both PR3-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and myeloperoxidase ANCA. The level of soluble interleukin-2 receptor was 1066 IU and that of haemoglobin (Hb) A1c was 7.7 mg/dL. Cocaine was not detected in a urine test. No other specific results were detected in the blood and urine tests. Histological examination showed only necrosis with no evidence of tumorous features or other specific findings. Immunostaining showed some inflammatory cells such as CD3 (+), CD79α (+), CD20 (+), CD79 α (+) and CD20 (−), as well as a few Epstein-Barr virus in situ hybridisation (+) cells; however, specific cell permeation and concentration were not observed. Grocott stain did not show any fungus. Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus and Corynebacterium were isolated in the bacterial culture of necrotic tissue.

Enhanced CT imaging revealed a slight contrasting effect in the middle and inferior nasal turbinate, and in the middle nasal meatus. A thickened membrane was also observed in the medial wall of the maxillary sinus. No tumorous lesion was evident (figure 2A, B). T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI of the lesion revealed moderate and high intensities, respectively (figure 2C,D). The lesion showed increased 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake (the maximum standard uptake value was 2.7, figure 3). However, no specific findings leading to a final diagnosis were obtained. Since the lesion was found to be deteriorating and extended to the opposite side of the nasal cavity at the second visit, we performed surgical debridement and biopsy under general anaesthesia on the 24th day after the first visit to our hospital. Histopathological examination led to a definitive diagnosis of actinomycosis (figure 4); however, the subtype of Actinomyces could not be detected in the bacterial culture.

Figure 2.

Enhanced CT (A and B) and MRI (C and D) of the paranasal sinuses. (A) Axial section: the common nasal meatus is filled with soft tissue, and the inferior turbinate is oedematous and enhanced. (B) Coronal section: the superior and middle meatus are filled with soft tissue density with slight enhancement, and the inferior turbinate is also slightly enhanced. (C) Axial enhanced T1-weighted sequence shows moderate enhancement of the nasal mucosa. (D) Axial T2-weighted image shows high intensity.

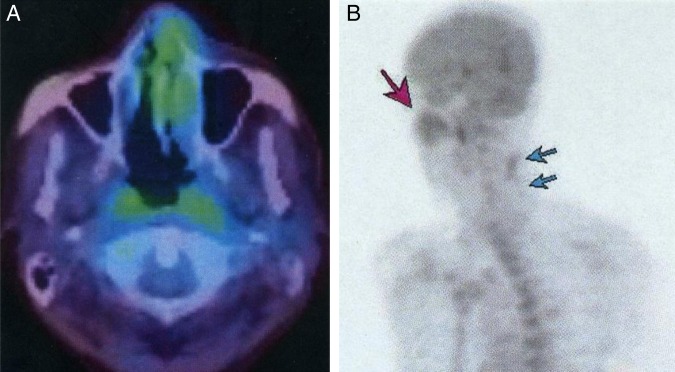

Figure 3.

Increased 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the lesion is seen on 18 fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography.

Figure 4.

Histopathological findings. (A) H&E staining (×40). (B) H&E staining in the magnified field (×400). The necrosis and Actinomyces are recognised in the membrane of the nasal cavity and trabecular bone. No filamentous branching structure is apparent. Neutrophilic infiltration is obvious, whereas that of lymphocytes is only slight. There are no signs of malignancy.

Treatment

Since the definitive diagnosis was invasive actinomycosis and radical excision was not performed, a long period of subsequent medical treatment was essential. The progression of necrosis was determined to be under control, and intranasal epithelisation was complete.

The patient received intravenous ampicillin/sulbactam (3 g/day) for 6 days in an inpatient setting, followed by the administration of oral amoxicillin at 1500 mg per day in an outpatient setting. However, 4 months later, he discontinued follow-up at the outpatient clinic. Three months after the discontinuation of visits, he reported that oral intake passed into his nasal cavity, and presented to the oral surgery centre in our hospital (figure 5). Since the necrosis in the lesion was progressing rapidly, surgical debridement of the hard palate and nasal cavity, including the nasal septum and lateral wall, was performed. Laboratory examination revealed a severe inflammatory reaction, including a WCC count of 14 910/μL, a CRP level of 10.8 mg/dL and an HbA1c level of 8.6 mg/dL. Treatment with intravenous panipenem/betamipron (1 g/day) and vancomycin (1 g/day) for 1 week was then planned. Three days after starting the antibiotics, the treatment had to be changed to intravenous penicillin G (8 million units/day) because of renal damage. The inflammatory reaction was gradually improved during the 10 days of this treatment. However, it had to be interrupted because of severe diarrhoea and abdominal pain. The administration of AMPC at 750 mg/day was started, and the abdominal symptoms improved.

Figure 5.

Fistula of the hard palate. (A) A view from the oral cavity. (B) An endoscopic view of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx. The left Eustachian tube is necrotic (arrows).

Outcome and follow-up

The patient then insisted on leaving the hospital and never came back to the outpatient clinic. Three months later, he was conveyed to our emergency centre because of bleeding from the oral cavity. Extreme emaciation was observed on admission (figure 6). Despite high-dose antibiotic therapy and nutritional management, his general condition deteriorated, and he died of multiple organ failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation caused by the local infection. The last laboratory examination was a WCC count of 2140/μL, a CRP level of 4.4 mg/dL, an Hb level of 5.3 g/dL, a platelet count of 2.8×104/μL, activated partial thromboplastin time of 60.3 s, prothrombin time (international normalised ratio) of 1.29, a fibrinogen level of 155 mg/dL and a D-dimer level of 90.2 μg/mL.

Figure 6.

CT images (A and B), a view from the oral cavity (C), and facial appearance (D). (A) CT axial section shows a subcutaneous mass that infiltrates the skin (arrow). (B) CT coronal section in a bone window shows erosion of the hard palate. (C) Enlarged fistula and necrosis of the hard palate. (D) Necrosis of the cheek skin around the nose.

Discussion

Actinomyces are microaerophilic Gram-positive bacteria, and normal flora in the upper and lower aerodigestive tracts; they cause actinomycosis, a chronic infectious disease with granulomatous and suppurative features. In actinomycosis, the commonly affected regions are the cervicofacial, pulmonothoracic and abdominopelvic, with the cervicofacial region being the area of predilection. The typical symptoms of actinomycosis are progressive pain, painful or painless swelling, skin colour change, board-like induration, abscess formation and porous fistula. In addition, several clinical symptoms are presented. Only a few reports have described cases of actinomycosis of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinus.1–6 Actinomycosis of these sites shows symptoms similar to those of sinusitis, such as nasal obstruction, purulent discharge, an oppressive feeling and facial swelling.3

Actinomycosis shows several clinical features and is categorised into three types according to the speed of progression: the acute type, which forms an abscess; chronic type, which mainly presents as fibrous changes; and subacute type, which is an intermediate between the acute and chronic types.7 8 It can also be classified as invasive or non-invasive type according to the manner of progression to the surrounding organs,3 4 which is useful in deciding treatment options.

Imaging to help determine a clinical diagnosis includes enhanced CT, MRI, ultrasonography, Ga scintigraphy and bone scintigraphy.4 9 Enhanced CT imaging is the most important technique and often shows a diffuse contrasting effect that indicates tumorous shadowing or a ring enhancement, which indicates the presence of an abscess.9 Since actinomycosis of the paranasal sinus and nasal cavity often shows erosion or destruction of the bone and invasion to the subcutaneous tissue and skin, these features are important in differentiating this condition from chronic sinusitis.4

The definitive diagnosis of actinomycosis requires confirmation of the presence of Actinomyces by bacteriological and/or histopathological examination. However, the detection rate of Actinomyces using bacteriological tests is not high because of its anaerobic nature, making a histological examination indispensable. Histological examination typically reveals acute purulent inflammation (abscess formation), a granuloma, chronic inflammation and healing, as evidenced mainly by the presence of fibrosis in the same lesion. A Gram-positive granular divergence-related short spawn is shown to be connected with others on H&E staining. An eosin stain-related club body (club) is radially arranged to its border, and neutrophils are attached to the tip of the club body. Numerous filament-formed cell bodies and plexuses are stained in black by Grocott staining.10 Although according to multiple histological examinations, malignant lymphoma and fungal invasion findings were negative in this case, it should be noted that these conditions cannot be completely ruled out, particularly considering that NK/T cell lymphoma is difficult to diagnose. Therefore, we should repeatedly perform the histological examinations to exclude other necrotic diseases that are difficult to diagnose.

The treatment for actinomycosis is antibiotic administration with or without surgical procedures. The recommended treatment is intravenous high-dose penicillin G (10–20 million units/day) for a few days to several weeks, followed by oral penicillin V (2–4 g/day) or amoxicillin for 3–12 months.3 5 11 Effective surgical options include abscess drainage, debridement and total resection. Since mixed infection with other bacteria affects the pathological progression of actinomycosis, these surgical procedures are important to control the infections and to increase the concentration of the antibiotics at the infection sites. It has been reported that a sole antibiotic treatment is not effective against paranasal actinomycosis,3 4 and the removal of the necrotic tissue by endoscopic sinus surgery is required before administering antibiotics for an appropriate period.

In the current case, Actinomyces caused necrosis of the nasal cavity; destroyed the inferior turbinate, nasal septum and maxillary bone; and possibly invaded the bone marrow. Since total resection of the lesion was not achieved at the first necrotomy, it was believed that the long-term administration of antibiotics at a high dose was required. However, this treatment could not be accomplished because of the adverse effects associated with intravenous delivery and the poor compliance of the patient with the subsequent oral antibiotics therapy, leading to the delivery of a less than adequate dose of antibiotics. Moreover, it was believed that the patient's immunocompromised state caused by uncontrolled diabetes mellitus made it difficult to control the infection. If there is time before initiating antibiotic treatment, aggressive debridement and partial maxillary resection can be performed with the consent of the patient until the definitive diagnosis has been established. Although we cannot be certain, it is possible that a total resection of the lesion when it was judged to be deteriorating could have prevented death in this case, even though total resection may have resulted in huge functional and aesthetic losses. In any case, management by both, surgical and medical treatments is difficult in the head and neck region when considering function preservation.

Conclusions

This case shows that local actinomycosis, such as maxillofacial or nasal actinomycosis, may result in death for immunocompromised patients who receive insufficient doses or intermittent dosage of antibiotics. Surgeons should be aware that actinomycosis can be an intractable and fatal disease, and progress should be monitored carefully so that treatment can be changed from medication to surgery if required.

Learning points.

Local actinomycosis in head and neck lesions can be an intractable and sometimes fatal disease.

Initial treatment is extremely important.

Insufficient dose or intermittent dosage of antibiotics may not be able to control an Actinomyces infection in a patient in an immunocompromised state.

Progression of necrosis may require extended radical resection.

Footnotes

Contributors: YS, YY and OS were directly involved in treating the patient, and all the authors drafted, read and confirmed the final draft of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sanchez Legaza E, Cercera Oliver C, Miranda Caravallo JI. Actinomycosis of the paranasal sinuses. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp 2013;64:310–11. 10.1016/j.otorri.2012.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batzakakis D, Karkos PD, Papouliakos S et al. Nasal actinomycosis mimicking a foreign body. Ear Nose Throat J 2013;92:E14–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vorasubin N, Wu AW, Day C et al. Invasive sinonasal actinomycosis: case report and literature review. Laryngoscope 2013;123:334–8. 10.1002/lary.23477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fadda GL, Gisolo M, Crosetti E et al. Intracranial complication of rhinosinusitis from actinomycosis of the paranasal sinuses: a rare case of abducens nerve palsy. Case Rep Otolaryngol 2014;2014:601671 10.1155/2014/601671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vinay K, Khullar G, Yadav S et al. Granulomatous invasive aspergillosis of paranasal sinuses masquerading as actinomycosis and review of published literature. Mycopathologia 2014;177:179–85. 10.1007/s11046-014-9732-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roth M, Montone KT. Actinomycosis of the paranasal sinuses: a case report and review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;114:818–21. 10.1016/S0194-5998(96)70109-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakagawa Y, Asada K, Doi Y et al. Oral and maxillofacial actinomycosis—clinical and bacterial studies of 13 cases. Jpn J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1985;31:110–15. 10.5794/jjoms.31.110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norman JE. Cervicofacial actinomycosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1970;29:735–45. 10.1016/0030-4220(70)90272-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park JK, Lee HK, Ha HK et al. Cervicofacial actinomycosis: CT and MR imaging findings in seven patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003;24:331–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ono T, Yoshida Y, Izumaru S et al. A case of nasopharyngeal actinomycosis leading to otitis media with effusion. Auris Nasus Larynx 2006;33:451–4. 10.1016/j.anl.2006.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta D, Willging JP. Pediatric salivary gland lesions. Semin Pediatr Surg 2006;15:76–84. 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2006.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]