Abstract

A 38-year-old woman presented with dysuria and fever. Her medical and family histories were unremarkable. CT scan of the abdomen revealed a polypoid mass of 4×2.6×2.2 cm. Her cystoscopy showed a 4×2 cm solid broad-based growth at trigone of the urinary bladder. She underwent transurethral resection of the urinary bladder tumour (TURBT). Histopathology revealed a poorly circumscribed proliferation of spindle cells arranged in a haphazard and fascicular manner along with many traversing blood vessels in a myxoid and hyalinised stroma. Immunohistochemistry was positive for anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1, smooth muscle actin, CD10, cytokeratin and desmin; and negative for CD34 and S-100 protein. Ki-67 proliferative index in the tumour was <1%. The patient was diagnosed as having inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour of the urinary bladder. After TURBT, her fever and urinary symptoms resolved. Her 1-month postoperative period was uneventful. She has been advised regular follow-up.

Background

In clinical practice, most urinary bladder tumours arise from the urothelial lining. Occurrences of soft-tissue tumours are rare in the urinary bladder.1 The benign soft-tissue tumours of the urinary bladder originate from smooth muscle cells (leiomyoma), endothelium (haemangioma), nerve sheath (neurofibroma) or myofibroblasts (inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour (IMT), postoperative spindle cell nodule (PSCN)). Of these, the IMT is a rare and interesting lesion, most commonly presenting with haematuria. It is rare to diagnose an IMT in the absence of haematuria. We report the rare occurrence of an IMT in the urinary bladder that clinically presented with dysuria and fever.

Case presentation

A 38-year-old woman presented with symptoms of burning and painful micturition for 2 months and fever for 10 days. She had no previous history of urinary symptoms and had not undergone bladder instrumentation. Her medical and family histories were unremarkable. Apart from hepatomegaly, her physical examination was unremarkable.

Investigations

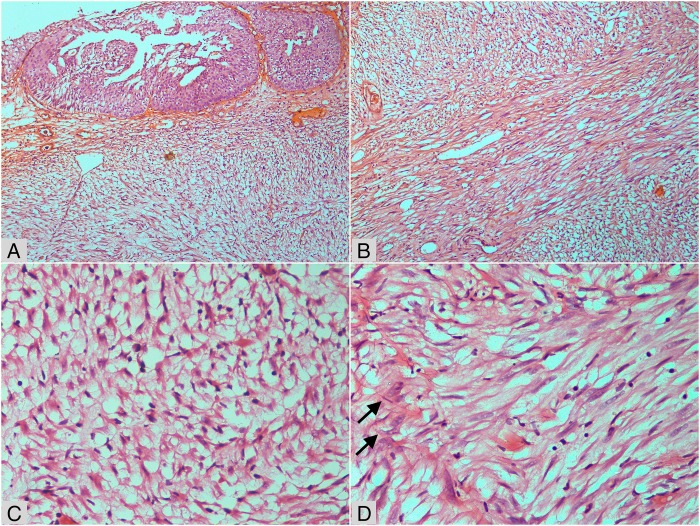

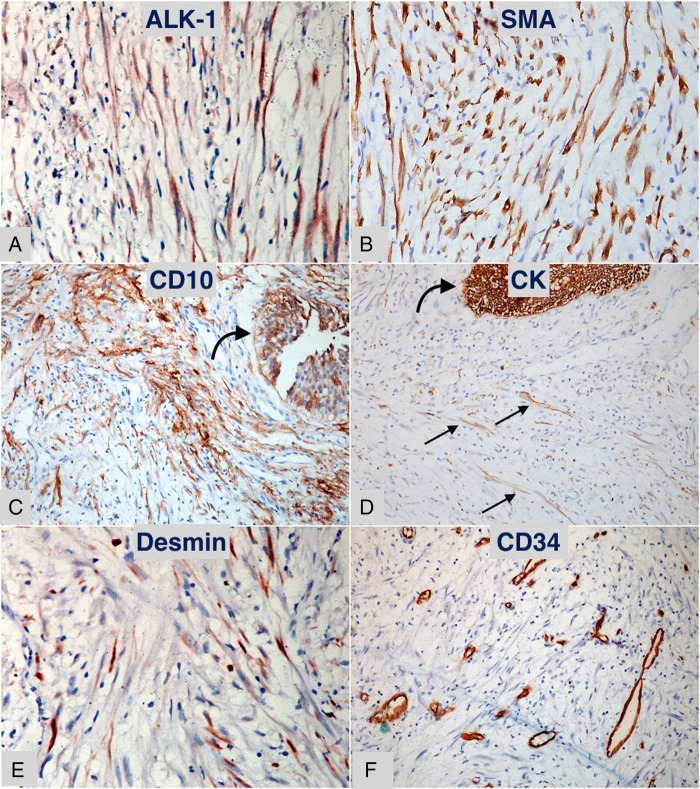

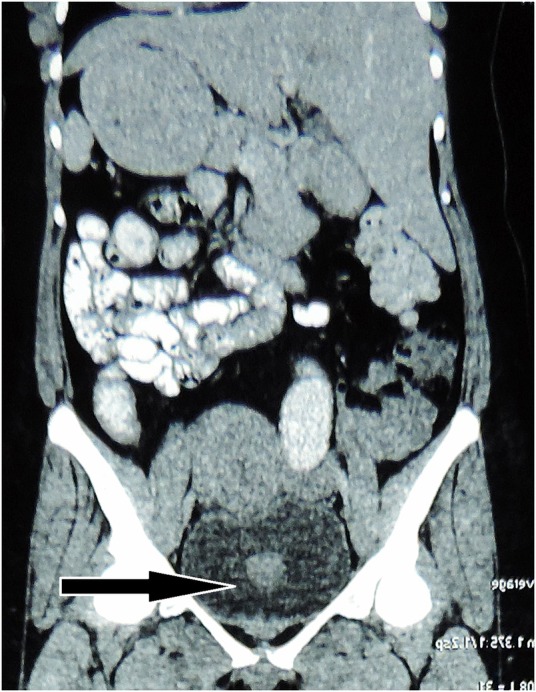

The patient's urine cytology was negative for malignant cells. Except for occasional pus cells, her urinalysis was unremarkable. Her urine cultures were sterile. All blood investigations were within normal limits. Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen revealed an ill-defined homogenously enhancing 4×2.6×2.2 cm polypoid mass arising from the posterior wall of the urinary bladder (figure 1). There were a few enlarged lymph nodes in the pre-aortic and para-aortic regions, the largest measuring 2.1×1.2 cm. The liver was enlarged, measuring 18 cm at the mid-clavicular line. Imaging of the other abdominal organs was unremarkable. With a provisional diagnosis of urinary bladder carcinoma and lymph node metastasis, the patient underwent transurethral resection of the bladder tumour. Per-operative cystoscopy examination showed a 4×2 cm solid broad-based growth at trigone, reaching up to the right posterior wall of the urinary bladder. Bilateral ureteral orifices were patent. Histological examination showed reactive urothelial lining with a poorly circumscribed underlying tumour composed of proliferating spindle cells arranged in a haphazard and fascicular manner with many traversing blood vessels (figure 2). The spindled tumour cells showed tapered elongated nuclei, mild nuclear atypia, inconspicuous nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm. The background stroma was myxoid to collagenised. Mitotic figures were occasional. There was uniform infiltrate of lymphocytes along with occasional plasma cells and neutrophils. Focally, necrosis was observed in the tumour. However, significant nuclear atypia, atypical mitotic figures or bizarre tumour cells, were not seen. Immunohistochemistry was performed using standard procedure on paraffin blocks, and was positive for anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1 (ALK-1), smooth muscle actin (SMA), CD10, cytokeratin (CK) focally and desmin; while it was negative for CD34 and S-100 protein (figure 3). The Ki-67 proliferation index was <1%.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan showing an enhancing polypoidal mass in the urinary bladder (arrow).

Figure 2.

H&E stained microphotographs of the tumour. (A) Part of the urothelial mucosa (top) with submucosal proliferation of myxoid tumour containing occasional prominent blood vessels (×100). (B) Fascicular pattern with prominent vascular spaces in myxoid and collagenised stroma (×200). (C) Plump cells on oedematous and myxoid background with scattered lymphocytes (×400). (D) Spindle cells with occasional enlarged atypical nuclei and prominent nucleoli (arrow) against a collagenised background (×400).

Figure 3.

Diaminobenzidine chromogen stained immunohistochemical sections of the lesion. (A) Anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1 positive myofibroblastic cells (×400). (B) Diffuse positivity for smooth muscle actin in myofibroblastic cells (×400). (C) CD10 positivity in urothelium (curved arrow) and underlying fascicles of myofibroblasts (×200). (D) Cytokeratin positive urothelium (curved arrow) with scattered positive myofibroblasts (small straight arrows) (×200). (E) Scattered focal desmin positive myofibroblasts (×400). (F) CD34 stain highlighting vascular channels, neighbouring tumour cells are negative (×200).

Differential diagnosis

Clinically, the differential diagnosis included urinary tract infection and urinary bladder carcinoma. The histopathological differential diagnoses considered in this case were: solitary fibrous tumour (SFT), IMT, leiomyoma, neurofibroma and PSCN . All these differential diagnoses are included under the following ‘Discussion’ heading.

Treatment

The patient was treated by transurethral resection of the bladder tumour (TURBT), followed by postoperative antibiotics and analgaesics.

Outcome and follow-up

Based on histopathology and immunohistochemistry, the final diagnosis was IMT of the urinary bladder. The bladder neck biopsy was free of tumour infiltration. After TURBT, the patient's fever subsided and dysuria resolved, and her 1-month postoperative follow-up was uneventful. She has been advised regular follow-up.

Discussion

The IMT is a rare benign spindle cell tumour of the urinary bladder, characterised by atypical spindle cell proliferation accompanied by lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate.1 In the past, IMT was known by various names such as inflammatory pseudosarcomatous fibromyxoid tumour, nodular fasciitis, pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic tumour and fibromyxoid pseudotumour.2 The first description of IMT in the urinary bladder was given by Roth in 1980.3 The most common presenting feature of bladder IMTs is painless gross haematuria; others include obstructive and/or irritative symptoms on voiding, abdominal pain and, rarely, constitutional symptoms such as fever and weight loss.1 4 Constitutional symptoms occur due to secretion of interleukins.5 Presentation of a bladder IMT with only constitutional symptoms—in the absence of haematuria—is very rare. Our patient, a young woman, presented with dysuria and fever without haematuria, which initially suggested a diagnosis of urinary tract infection. Later, revelation of a polypoidal mass in the bladder and abdominal lymphadenopathy suggested radiological diagnosis of bladder carcinoma in this case. However, subsequent work up confirmed the diagnosis of IMT. A similar case in a 69-year-old woman with bladder mass and enlarged pelvic lymph nodes was diagnosed as IMT of the bladder with non-malignant lymph nodes.6

Grossly, bladder IMT is seen as a polyp or a submucosal nodule with or without surface ulceration; with a pale, soft and gelatinous cut surface.1 Histologically, the IMT lesion is characterised by the proliferation of myofibroblasts with prominent blood vessels and inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells in a myxoid to collagenised stroma.1 The lesional myofibroblasts are spindle-shaped cells that show elongated eosinophilic cytoplasmic processes, bland nuclei with occasional large atypical nuclei and occasional nucleoli. Three basic histological patterns have been described in IMTs, which are often seen in combination within the same tumour: (1) a myxoid/vascular pattern, (2) a dense spindle cell pattern and (3) a hypocellular fibrous (fibromatosis-like) pattern.5 The first pattern is composed of loosely arranged plump cells in myxoid or oedematous stroma with conspicuous blood vessels. The second pattern shows packed fascicles of spindle cells with an admixture of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The third pattern is made up of elongated cells in a densely collagenised stroma with scattered inflammatory cells. Immunohistochemically, IMT expresses ALK-1 in 87.5% cases, SMA in 90% cases, pancytokeratin focally in >50% cases and desmin in ≈50% cases.6 7 We demonstrated expression of all these markers; however, expression of ALK-1 confirmed the diagnosis of IMT. In addition, we also observed expression of CD10 as noticed in a recently published study.8

Histopathologically, IMT mimics myriad spindle cell lesions—both benign and malignant. The differential diagnoses considered in this case were SFT, leiomyoma, neurofibroma and PSCN. SFT is an extremely rare tumour of the bladder, depicted by proliferation of non-descript spindle cells with prominent vasculature in a fibrocollagenous stroma. In comparison to IMT, SFT shows characteristic diffuse and strong CD34 positivity, and nuclear expression of STAT6, besides bcl-2+/CD99+/SMA−. Leiomyoma of the urinary bladder is a rare tumour that shows intersecting fascicles of smooth muscle bundles without atypia and diffuse strong SMA+/desmin+/vimentin+; as well as CD34±/CK−/S-100−. Neurofibroma, a rare tumour of the nerve sheath, usually shows fascicles of spindle cells with wavy nuclei on a collagenised background. Immunohistochemistry of neurofibroma will be S-100+/type-IV collagen + with EMA−/CK−. PSCN is a tumour of myofibroblastic origin that shares almost all histopathological and immunohistochemical features of IMT. However, in contrast to IMT, PSCN is usually <1 cm in size and arises in the setting of previous instrumentation or surgery of the urinary bladder.7 Finally, IMT can be misinterpreted as a malignant tumour (rhabdomyosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma and sarcomatoid carcinoma) on histopathology.1 7 However, we did not observe convincing histopathological features of malignancy in this case.

Usual treatment options for a bladder IMT include transurethral resection of the tumour, or partial cystectomy; rarely, radical cystectomy has been performed.2 9 Partial cystectomy by a laparoscopic approach has also been used successfully.9 Nevertheless, complete resection and follow-up is the treatment of choice. The local recurrence rate after excision is 10%.7 A follow-up is advised in these patients, as a 71-year-old man had multiple recurrences and distant metastases of the bladder IMT that rapidly progressed and culminated in death.10

Learning points.

When a young patient presents with symptoms of urinary tract infection and fever, along with a mass lesion in the urinary bladder, a diagnosis of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour (IMT) should be suspected.

IMT is a rare but distinctive neoplasm of the urinary bladder that should be accurately diagnosed.

Biopsy examination and immunohistochemistry plays a pivotal role in confirmation of diagnosis.

Surgical resection and follow-up are both included in the gold standard treatment.

Accurate and timely diagnosis alleviates the patient's concerns and prevents overtreatment in the form of unwarranted radical cystectomy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Khushbu Gahoi for collecting the patient's history and to Mr Kanhaiya Lal, Mr Yogendra K Verma and Mr Vikash Agarwal for their assistance in immunohistochemistry.

Footnotes

Contributors: SCUP carried out the histopathological and immunohistochemical studies, conceived the study, and drafted, edited and revised the manuscript. RK carried out the literature search and revised the manuscript. DC collected the data, searched the literature and prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. ST participated in the conception and design of the study, and performed the clinical studies. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lott S, Lopez-Beltran A, Maclennan GT et al. Soft tissue tumors of the urinary bladder, part I: myofibroblastic proliferations, benign neoplasms, and tumors of uncertain malignant potential. Hum Pathol 2007;38:807–23. 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harik LR, Merino C, Coindre JM et al. Pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferations of the bladder: a clinicopathologic study of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:787–94. 10.1097/01.pas.0000208903.46354.6f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roth JA. Reactive pseudosarcomatous response in urinary bladder. Urology 1980;16:635–7. 10.1016/0090-4295(80)90578-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alquati S, Gira FA, Bartoli V et al. Low-grade myofibroblastic proliferations of the urinary bladder. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2013;137:1117–28. 10.5858/arpa.2012-0326-RA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR et al. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor). A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1995; 19:859–72. 10.1097/00000478-199508000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Machioka K, Kitagawa Y, Izumi K et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the urinary bladder with benign pelvic lymph node enlargement: a case report. Case Rep Oncol 2014;7:571–5. 10.1159/000366269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alderman M, Kunju LP. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the bladder. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2014;138:1272–7. 10.5858/arpa.2014-0274-CC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parra-Herran C, Quick CM, Howitt BE et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the uterus: clinical and pathologic review of 10 cases including a subset with aggressive clinical course. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:157–68. 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pradhan MR, Ranjan P, Rao RN et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the urinary bladder managed by laparoscopic partial cystectomy. Korean J Urol 2013;54:797–800. 10.4111/kju.2013.54.11.797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HW, Choi YH, Kang SM et al. Malignant inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the bladder with rapid progression. Korean J Urol 2012;53:657–61. 10.4111/kju.2012.53.9.657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]