Abstract

An international collaborative project has been proposed to inactivate all mouse genes in embryonic stem (ES) cells using a combination of random and targeted insertional mutagenesis techniques. Random gene trapping will be the first choice in the initial phase, and gene-targeting experiments will then be carried out to individually knockout the remaining ‘difficult-to-trap’ genes. One of the most favored techniques of random insertional mutagenesis is promoter trapping, which only disrupts actively transcribed genes. Polyadenylation (poly-A) trapping, on the other hand, can capture a broader spectrum of genes including those not expressed in the target cells, but we noticed that it inevitably selects for the vector integration into the last introns of the trapped genes. Here, we present evidence that this remarkable skewing is caused by the degradation of a selectable-marker mRNA used for poly-A trapping via an mRNA-surveillance mechanism, nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD). We also report the development of a novel poly-A-trap strategy, UPATrap, which suppresses NMD of the selectable-marker mRNA and permits the trapping of transcriptionally silent genes without a bias in the vector-integration site. We believe the UPATrap technology enables a simple and straightforward approach to the unbiased inactivation of all mouse genes in ES cells.

INTRODUCTION

With the animal genome sequencing projects approaching their completion, the next big task for our bioscience research communities is to rapidly and efficiently elucidate physiological functions in animals of the vast number of newly discovered genes and gene candidates.

Recently, an international collaborative project has been proposed to inactivate all mouse genes in ES cells within five years using a combination of random and targeted insertional mutagenesis techniques (1). To disrupt as many genes in ES cells as possible within a limited period of time, gene trapping will first be employed because it is simple, rapid and cost-effective (2). Genes incapable of being captured by standard gene-trap techniques will then be subjected to labor-intensive and time-consuming gene-targeting experiments (1). Therefore, it is essential for the success of the project to establish an efficient gene-trap strategy suited to universally target genes in ES cells.

One of the most commonly used gene-trap methods is promoter trapping, which involves a gene-trap vector containing a promoterless selectable-marker cassette (3–6). In promoter trapping, the mRNA of the selectable-marker gene can be transcribed only when the gene-trap vector is placed under the control of an active promoter of a trapped gene. Although promoter trapping is effective at inactivating genes, transcriptionally silent loci in the target cells cannot be identified by this strategy. To capture a broader spectrum of genes including those not expressed in the target cells, poly-A-trap vectors have been developed in which a constitutive promoter drives the expression of a selectable-marker gene lacking a poly-A signal (7–10). In this strategy, the mRNA of the selectable-marker gene can be stabilized upon trapping of a poly-A signal of an endogenous gene regardless of its expression status in the target cells.

Here, we show that despite the broader spectrum of its potential targets, poly-A trapping inevitably selects for the vector integration into the last introns of the trapped genes, resulting in the deletion of only a limited C-terminal portion of the protein encoded by the last exon of the trapped gene. We present evidence that this remarkable skewing is created by the degradation of a selectable-marker mRNA used for poly-A trapping via an mRNA-surveillance mechanism, NMD. The NMD pathway is universally conserved among eukaryotes and is responsible for the degradation of mRNAs with potentially harmful nonsense mutations (11–13). We also show that an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) sequence (14) inserted downstream of the authentic termination codon (TC) of the selectable-marker mRNA prevents the molecule from undergoing NMD, and makes it possible to trap transcriptionally silent genes without a bias in the vector-integration site. We believe this novel anti-NMD technology, termed UPATrap, could be used as one of the most powerful and straightforward strategies for the unbiased inactivation of all mouse genes in the genome of ES cells (1).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vector construction

To create the UPATrap retrovirus vector, two minor alterations and one major modification were introduced into the conventional RET poly-A-trap vector (10). The loxP signal (a 44 bp EcoRI–BamHI fragment) in the 3′ LTR (long terminal repeat) of the RET vector was replaced with a synthetic Flp-recombinase target (FRT) sequence (15), and a 726 bp NcoI–NsiI fragment containing an entire coding sequence of hrGFP (green fluorescence protein) (Stratagene), which had been generated by PCR, was ligated with the vector after removal of the original EGFP (enhanced GFP) sequence by NcoI–NsiI double digestion. Then, the IRES sequence flanked by two tandem loxP signals, three initiation codons (ICs) in all reading frames, and a modified version of the mouse hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase gene (hprt) exon 8 splice donor (SD) sequence generated by PCR were inserted downstream of the NEO (a gene segment that confers resistance to a neomycin analog, G418) coding sequence in the altered RET vector after removal of the corresponding region (213 bp) by MluI–AatII double digestion. Details of these changes in the UPATrap vector are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. The nucleotide sequences of PCR primers used for the construction of the UPATrap vector are available on request.

Culture and manipulation of ES cells

ES cell culturing, production of recombinant retroviruses, gene trapping and isolation of cDNA fragments of trapped genes were carried out as previously described (10), except that TC1 (16) and V6.4 (17) ES cell lines were used instead. For excision of the floxed IRES sequence, two ES cell clones (15v-19 and 15v-43) in which different genes (Pde9a and Nf2) had been trapped by the UPATrap vector were electroporated as previously described (16) with a Cre recombinase-encoding plasmid pCAGGS-NLS/Cre (9). Subclones were then isolated by limiting dilution, and recombination events and clonality of the cells were analyzed by genomic PCR. The primer sequences are available on request.

Bioinformatics

Before detailed analyses, the nucleotide sequences of the trapped cDNA fragments were filtered using information available in public genome databases [University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) mouse genome assembly and Ensembl mouse genome database] to eliminate repetitive and low-quality fragments. To determine the number of exons in the trapped genes and integration sites of the gene-trap vectors, we used the mouse BLAT search provided by UCSC. Homology searches were performed using the non-redundant (NR) and expressed sequence tag (EST) databases of National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) in conjunction with the BLAST algorithm. Identity or similarity extending more than ∼100 bp with the probability E value of 10−20 or less was considered to be significant homology. Information regarding the EST clones, especially their origins, was obtained from the Unigene database at NCBI.

Gene expression analyses

Total RNA was prepared from ES cells using Sepasol reagent (Nacalai) or from mouse tissues using a guanidine method (18). Reverse transcription was then performed using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and pd (T)12–18 primer (Amersham) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was carried out using Advantage-GC2 polymerase mix (BD Biosciences) (36 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 62°C for 30 s and 72°C for 90 s). Real-time PCR was performed following the relative standard curve method (Applied Biosystems 7700 User Bulletin #2) using SYBR Green Master Mix and an Applied Biosystems Prism 7700 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems). Reactions were performed in 3–4 replicates of cDNA samples for each clone. The levels of transcripts to be analyzed were normalized to those of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNAs. For the NMD-inhibition experiments, we treated 60% confluent cells with 100 μg/ml of emetine dihydrochloride hydrate (Sigma) at 37°C for 10 h before preparation of total RNA. The DNA probes used for northern hybridization included a 0.8 kb BamHI–BamHI fragment containing an NEO coding sequence in the original RET vector (9) and a 0.3 kb EcoRI–EcoRI fragment derived from the 3′ untranslated (UT) region of the mouse β-actin cDNA (19) labeled with 32P using a random-priming kit (TAKARA). Hybridization, washing and autoradiographic analysis of the filters were carried out under standard conditions (19). The primer sequences used for PCR are available on request.

URLs

The UCSC Genome Browser is available at http://genome.ucsc.edu/. The Ensembl Genome Browser is available at http://www.ensembl.org/. The BLAST search of NCBI's NR and EST databases is available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/. The Unigene database is available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/UniGene/. The NAISTrap database is available at http://bsw3.naist.jp/kawaichi/naistrap.html.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Strong bias in the vector-integration site in poly-A trapping

We have generated a collection of mutated mouse ES cell clones by using a poly-A-trap vector, RET (Figure 1A), established the NAISTrap database, and subsequently constructed DNA arrays of trapped gene fragments (9,10). We found that a high proportion (88%) of the trapped genes had insertional mutations in their last (3′-most) introns (see Table 1 for examples). This phenomenon is not specific to our RET system because another research group using poly-A trapping (20) has also experienced this same bias (see Supplementary Material for details). In general, the chance of producing a null allele becomes small with insertion of the gene-trap vector into the last intron because such an event results in the deletion of only a limited C-terminal portion of the protein encoded by the last exon of the trapped gene. This strong skewing in the vector-integration site was suspected to be caused by an mRNA-surveillance mechanism, NMD (11–13).

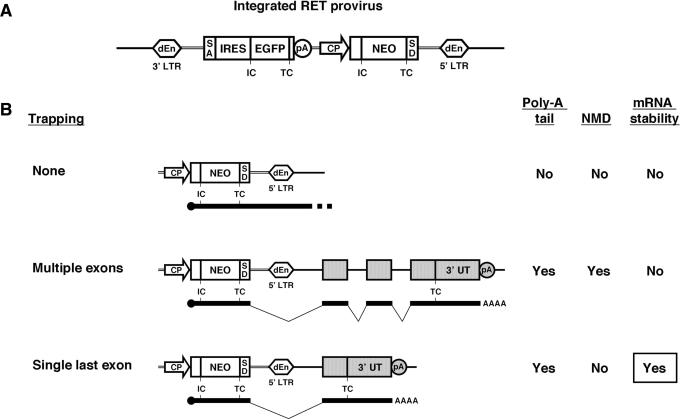

Figure 1.

A model showing a biased selection of the vector-integration sites in poly-A trapping. (A) Structure of the RET provirus integrated into the genome of infected cells (10). IC, initiation codon; TC, termination codon; dEn, enhancer deletion; LTR, long terminal repeat; SA, splice acceptor; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescence protein; pA, poly-A-addition signal; CP, constitutive promoter; SD, splice donor. (B) Integration sites of a poly-A-trap retrovirus vector and stability of a selectable-marker mRNA. Trapped exons are depicted as gray boxes. The NEO pre-mRNA driven by a CP must utilize a pA of an endogenous gene to acquire a poly-A tail for its stabilization. When multiple exons are trapped, however, the TC of the NEO cassette is recognized as premature, and the NEO-trapped gene fusion transcripts are degraded by NMD.

Table 1.

Known genes and their exons trapped using the RET poly-A-trap vector

| Gene identity | Total number of exons | Number of trapped exonsa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene symbol | Accession number | ||

| A630021E21Rik | AK080278 | 4 | 1 |

| A930013B10Rik | NM_001001497 | 3 | 1 |

| A930017E24Rik | NM_177041 | 9 | 1 |

| Atox1 | NM_009720 | 4 | 1 |

| Bach | NM_133348 | 9 | 1 |

| BC061259 | AK037138 | 3 | 1 |

| Bub1b | NM_009773 | 23 | 1 |

| Cd47 | NM_010581 | 10 | 1 |

| Cdc42 | NM_009861 | 6 | 1 |

| Cfdp1 | NM_011801 | 7 | 1 |

| Commd5 | NM_025536 | 3 | 1 |

| Copg | NM_017477 | 24 | 1 |

| Crk | NM_133656 | 3 | 1 |

| D10Ertd322e | NM_026065 | 6 | 1 |

| D11Ertd603e | NM_026023 | 4 | 1 |

| D3Jfr1 | NM_144901 | 20 | 1 |

| D430024F16Rik | NM_178698 | 4 | 1 |

| E030012C15Rik | AK053136 | 3 | 1 |

| Eps15-rs | NM_007944 | 24 | 1 |

| Erh | NM_007951 | 4 | 1 |

| Falz | BC037661 | 9 | 8 |

| Fcgr2b | NM_010187 | 8 | 2 |

| Fntb | NM_145927 | 12 | 1 |

| Fthfsdc1 | NM_172308 | 28 | 1 |

| Gabarapl2 | NM_026693 | 5 | 1 |

| Gpc3 | NM_016697 | 8 | 1 |

| Gpi1 | NM_008155 | 18 | 16 |

| Gpr1 | NM_146250 | 3 | 1 |

| Hrasls3 | NM_139269 | 5 | 1 |

| Ifitm1 | NM_026820 | 3 | 2 |

| Il17d | NM_145837 | 3 | 1 |

| IMAGE:3494995 | BC046463 | 19 | 3 |

| Immp2l | NM_053122 | 7 | 1 |

| Lgals7 | NM_008496 | 4 | 1 |

| Lman2 | NM_025828 | 8 | 1 |

| Lsm7 | NM_025349 | 4 | 1 |

| Manbal | AK007599 | 3 | 1 |

| Mrps27 | NM_173757 | 11 | 1 |

| Mrps31 | NM_020560 | 7 | 1 |

| Msra | NM_026322 | 6 | 1 |

| Ndg2 | NM_175329 | 4 | 1 |

| Ndufa7 | NM_023202 | 4 | 1 |

| Npr1 | NM_008727 | 23 | 1 |

| Nt5c1b | NM_027588 | 9 | 1 |

| Pecam1 | BC008519 | 14 | 1 |

| Pfdn1 | NM_026027 | 4 | 1 |

| Plvap | NM_032398 | 6 | 1 |

| Popdc2 | NM_022318 | 4 | 1 |

| Praf2 | NM_138602 | 3 | 1 |

| Prcc | NM_033573 | 7 | 1 |

| Pum1 | NM_030722 | 22 | 2 |

| Rab27a | NM_023635 | 6 | 1 |

| Ralgps1 | NM_175211 | 20 | 19 |

| Rbks | NM_153196 | 8 | 1 |

| Rpl23 | NM_022891 | 5 | 4 |

| Sdsl | NM_133902 | 8 | 1 |

| Sgce | NM_011360 | 11 | 1 |

| Sult2b1 | NM_017465 | 7 | 1 |

| Tada3l | NM_133932 | 9 | 1 |

| Tpst1 | NM_013837 | 6 | 5 |

| Yars | NM_134151 | 13 | 1 |

| Ywhaz | NM_011740 | 7 | 1 |

| Zcchc10 | NM_026479 | 4 | 1 |

| Zfp297b | NM_027947 | 4 | 1 |

| 1110008L16Rik | AK031144 | 7 | 1 |

| 1110014C03Rik | NM_026775 | 4 | 1 |

| 1110014D18Rik | NM_026746 | 7 | 1 |

| 1110031B06Rik | NM_144521 | 5 | 1 |

| 1600010M07Rik | AK005418 | 4 | 1 |

| 1810013L24Rik | AK007485 | 4 | 2 |

| 2600006L11Rik | AK011166 | 3 | 1 |

| 2610033C09Rik | NM_026407 | 9 | 1 |

| 2810410M20Rik | NM_024428 | 5 | 1 |

| 2810417J12Rik | NM_029798 | 3 | 1 |

| 2900010M23Rik | NM_026063 | 4 | 1 |

| 4930579G22Rik | NM_026916 | 3 | 1 |

| 4930583C14Rik | NM_029472 | 5 | 1 |

| 4933427L07Rik | NM_027727 | 17 | 1 |

| 4933439F18Rik | NM_025757 | 6 | 1 |

| 9230116N13Rik | AK033832 | 3 | 2 |

aNumber of exons downstream of vector-integration site. Genes consisting of two exons were excluded from analysis.

In mammalian cells, a TC is recognized as premature if it is located greater than ∼60 nt 5′ to the last exon–exon junction, and an mRNA containing such a premature TC (PTC) is degraded by NMD. In contrast, NMD does not function if a TC is generated within ∼60 nt upstream from the last exon–exon junction, or anywhere inside the last exon (21,22). We hypothesized that the TC of the NEO cassette of the RET vector would be recognized as a PTC when it is inserted into one of the upstream introns (other than the last one) of a trapped gene, and as a consequence the NEO-trapped gene fusion transcript would undergo NMD (Figure 1B). On the other hand, if the RET vector is integrated into the last intron of a gene, the NEO mRNA would be able to narrowly escape degradation because the distance between the NEO TC and the last exon–exon junction [64 nt in the case of the RET vector (10)] is probably too short to efficiently induce NMD (21,22) (Figure 1B).

Development of a novel strategy for unbiased poly-A trapping

To test the above hypothesis and also overcome the serious problem of the strongly skewed selection of the vector-integration sites in poly-A trapping, we developed a novel strategy, termed UPATrap (Figure 2A). In brief, an IRES sequence (14) flanked by two tandem loxP signals and three initiation codons in all three reading frames were inserted between the NEO TC and the SD sequence of the conventional RET vector (10) (see Supplementary Figure 1 for details). By adding these modifications, we attempted to induce internal initiation of translation that would proceed toward the end of the NEO fusion transcript. The inserted IRES sequence is flanked by two loxP signals for the purpose of deleting the IRES-mediated translation of abnormal proteins in mutant mice derived from gene-trapped ES cell clones. In the absence of IRES, only the NEO protein is translated from the NEO-trapped gene fusion transcripts because of the monocistronic rule of eukaryotic translation.

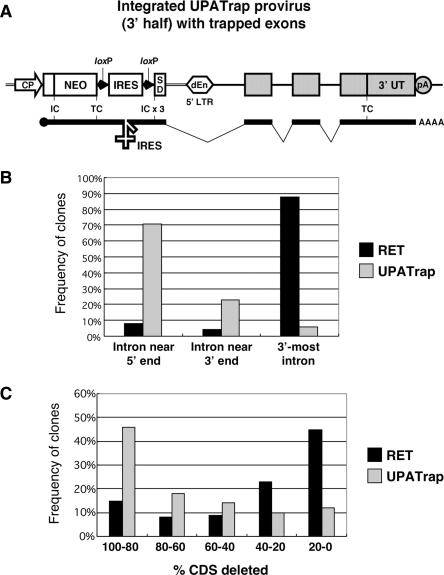

Figure 2.

Unbiased gene trapping using the UPATrap vector. (A) Critical elements in the UPATrap vector. The IRES sequence flanked by two tandem loxP signals and three ICs (IC × 3) were inserted between the NEO TC and SD sequence of the RET vector (10) (see Supplementary Figure 1 for details). Components other than the NEO cassette of the RET vector were basically unchanged, and several useful features including the high gene-disruption efficiency of the vector (9,10) have been utilized in the UPATrap system. Trapped exons are depicted as gray boxes. (B) Distribution of the vector-insertion sites within trapped genes. To identify the insertion sites, gene-trap sequence tags were analyzed for 200 ES cell clones in which known genes had been trapped using the RET (100 clones) or the UPATrap (100 clones) vector. Insertion events in the known genes consisting of only two exons were excluded from the analysis. Introns near the 5′ and 3′ ends were defined as being located 5′ and 3′ to the middle exon or intron of a gene, respectively. The number of events with vector integration into the 3′-most (last) introns were independently counted and excluded from those associated with vector integration into introns near 3′ ends. (C) Size of the deduced protein deletions due to gene trapping. The proportions of protein-coding sequences (CDSs) located 3′ to the vector-integration sites were analyzed for 200 ES cell clones in which known genes had been trapped using the RET (100 clones) or the UPATrap (100 clones) vector.

The UPATrap retrovirus vector was used to infect mouse ES cells, and G418-resistant clones were then selected. After obtaining cDNA fragments of the trapped genes by 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (3′ RACE) from the downstream portions of the NEO-trapped gene fusion transcripts, we determined their nucleotide sequences to generate gene-trap sequence tags and assessed intragenic distribution of the vector-integration sites for one hundred known genes. As shown in Figure 2B, 71 clones (71%) had insertional mutations in the upstream regions of the trapped genes, and multiple downstream exons were disrupted by the vector integration (see Table 2 for examples). Only six clones (6%) carried an insertion in the 3′-most intron of the trapped gene. The size of the deduced protein deletions due to gene trapping was also significantly larger for the UPATrap than for the standard poly-A-trapping method (Figure 2C). These data indicate that the strongly biased selection of the vector-integration sites in a standard poly-A-trap strategy was corrected for by the UPATrap system. Rather, ES cell clones which integrated the UPATrap vector near the 5′ end of genes were frequently isolated, probably reflecting the integration-site preference of Moloney murine leukemia virus (23). A preliminary analysis (n = 50) also showed that there was no strong skewing in the reading-frame pattern of the trapped gene portion. In 34%, 24% and 42% of the clones, the trapped exons used the reading frames of the ICs #1, #2 and #3, respectively, located downstream of the IRES sequence in the NEO cassette of the UPATrap vector.

Table 2.

Known genes and their exons trapped using the UPATrap vector

| Gene identity | Total number of exons | Number of trapped exonsa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene symbol | Accession number | ||

| A4galt | NM_001004150 | 3 | 2 |

| Aldh3b1 | NM_026316 | 10 | 8 |

| Ankrd25 | NM_145611 | 12 | 9 |

| Apg5l | NM_053069 | 8 | 3 |

| Arf2 | NM_007477 | 5 | 4 |

| Bcl2 | NM_009741 | 3 | 1 |

| Blmh | NM_178645 | 12 | 6 |

| C330011J12Rik | AK049181 | 12 | 1 |

| C730048E16Rik | NM_144849 | 8 | 7 |

| Ccnc | NM_016746 | 12 | 3 |

| Ccnd3 | AK083384 | 7 | 6 |

| Cidea | NM_007702 | 5 | 2 |

| Commd7 | NM_133850 | 7 | 4 |

| Crip1 | AK088267 | 5 | 3 |

| Ctnnbl1 | NM_025680 | 16 | 5 |

| D8Ertd354e | AK035264 | 18 | 13 |

| Dap3 | NM_022994 | 13 | 6 |

| Dia1 | NM_029787 | 9 | 8 |

| Dnm2 | NM_007871 | 19 | 18 |

| Eif4ebp1 | NM_007918 | 3 | 2 |

| Emp1 | NM_010128 | 5 | 4 |

| Eno1 | NM_023119 | 12 | 11 |

| Eno3 | AK002485 | 12 | 11 |

| Epn2 | NM_010148 | 10 | 4 |

| Exosc1 | NM_025644 | 8 | 6 |

| Fgd1 | NM_008001 | 18 | 17 |

| Fnbp1 | NM_019406 | 9 | 3 |

| Folr2 | NM_008035 | 6 | 3 |

| Golph2 | NM_027307 | 10 | 7 |

| Grb10 | NM_010345 | 16 | 11 |

| Grb7 | NM_010346 | 15 | 14 |

| Gstp1 | NM_013541 | 7 | 6 |

| Hip2 | NM_016786 | 7 | 4 |

| Hnrpc | NM_016884 | 10 | 5 |

| Jarid1b | NM_152895 | 27 | 26 |

| Kif27 | NM_175214 | 17 | 2 |

| Kremen | NM_032396 | 9 | 7 |

| Lman2l | BC046969 | 8 | 7 |

| M6prbp1 | NM_025836 | 8 | 7 |

| Macf | AF150755 | 94 | 93 |

| MGC:99447 | BC072561 | 20 | 7 |

| Mip | NM_008600 | 4 | 3 |

| mKIAA0978 | AK122413 | 12 | 11 |

| Nbr1 | NM_008676 | 24 | 13 |

| Nf2 | NM_010898 | 16 | 11 |

| Nolc1 | AK034817 | 13 | 12 |

| Nosip | NM_025533 | 9 | 8 |

| Npl | NM_028749 | 12 | 8 |

| Nup205 | AK129093 | 43 | 7 |

| Pcyt1a | NM_009981 | 9 | 6 |

| Pde9a | NM_008804 | 19 | 15 |

| Polr2e | BC045521 | 7 | 5 |

| Pomt1 | NM_145145 | 20 | 11 |

| Prkar2a | NM_008924 | 10 | 9 |

| Prx | NM_019412 | 6 | 5 |

| Psmd7 | NM_010817 | 7 | 4 |

| Rarg | NM_011244 | 10 | 1 |

| Rnf111 | NM_033604 | 15 | 12 |

| Scrib | NM_134089 | 38 | 9 |

| Sec24a | NM_175255 | 23 | 22 |

| Sema4b | NM_013659 | 14 | 10 |

| Sirt6 | NM_181586 | 8 | 6 |

| Slc12a4 | NM_009195 | 24 | 23 |

| Sox5 | AK029047 | 12 | 11 |

| Src | BC039953 | 14 | 13 |

| Tacc3 | NM_011524 | 16 | 15 |

| Tcfap4 | NM_031182 | 7 | 6 |

| Tef | AY540631 | 4 | 3 |

| Terf2 | NM_009353 | 9 | 7 |

| Tgfb1i4 | NM_009366 | 3 | 2 |

| Ube2d2 | NM_019912 | 7 | 6 |

| Y1G0138J11 | AK201545 | 4 | 2 |

| Zfp346 | NM_012017 | 7 | 2 |

| 1100001D10Rik | BC061692 | 15 | 4 |

| 1110003H10Rik | BC064456 | 4 | 3 |

| 1700073K01Rik | NM_026626 | 7 | 4 |

| 2200001I15Rik | NM_183278 | 3 | 2 |

| 2310061L18Rik | BC072561 | 20 | 7 |

| 4632409L19Rik | AK040612 | 19 | 18 |

| 4930447K03 | AK015408 | 5 | 1 |

aNumber of exons downstream of vector-integration site. Genes consisting of two exons were excluded from analysis.

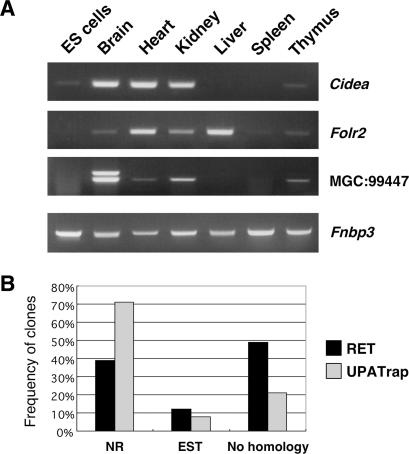

Next, we analyzed the nature of genes identified using the UPATrap system. Since 41 out of 80 genes listed in Table 2 do not have corresponding expressed sequence tags (ESTs) in current databases which have been derived from undifferentiated ES cells (data not shown), mRNA expression in ES cells was examined for six of these genes using the reverse transcription-mediated polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR), and we found that three did not give rise to discrete cDNA bands (Figure 3A). This indicates that transcriptionally inactive genes in ES cells can be trapped using the UPATrap vector as expected for poly-A-trapping strategies in general. Then, the GenBank homology analysis was performed for the whole range of sequence tags isolated in the UPATrap experiments to elucidate the spectrum of genes disrupted using this system. As shown in Figure 3B, the proportion of matches to known (non-redundant) genes increased by 32% as compared to the previously obtained data using the conventional RET vector, suggesting that the improvement of the vector design reduced the rate of ES cell clones in which non-functional DNA segments had been trapped as artifact. The molecular basis for the contrasting nature of poly-A trapping created by the RET and UPATrap vectors (Figures 2 and 3) can only be explained by the structural difference in their NEO cassettes because a variant of the UPATrap vector containing EGFP instead of hrGFP showed a pattern of poly-A trapping identical to that of the original UPATrap vector (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Nature of genes trapped using the UPATrap vector. (A) Disruption of genes that are not expressed in ES cells. The absence and presence of gene expression in undifferentiated ES cells and mouse tissues, respectively, were confirmed by RT–PCR. The ubiquitously expressed Fnbp3 mRNA (24) was used as an internal control. (B) Identity of genes disrupted using the UPATrap vector. After eliminating repetitive and low-quality sequences, 100 trapped genes were randomly chosen for each strategy (RET or UPATrap) and classified as previously described (10).

Suppression of NMD permits unbiased gene trapping

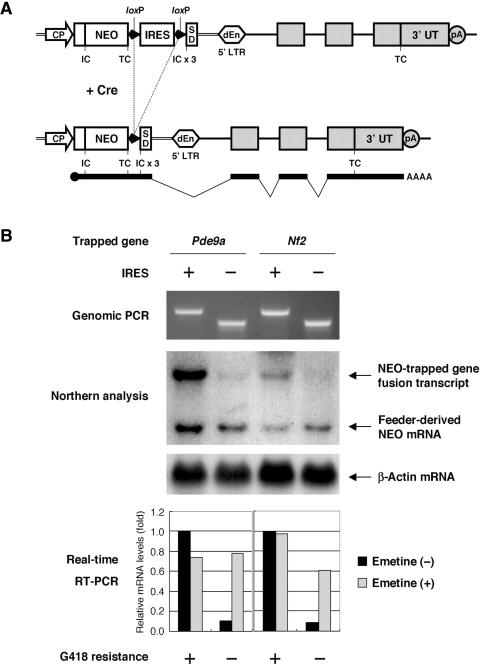

To examine whether unbiased poly-A trapping was made possible by the IRES-mediated suppression of NMD, we performed Cre-mediated excision of the floxed IRES portion from the genome of two ES cell clones in which multiple downstream exons of different genes had been trapped using the UPATrap vector (Figure 4A). Our prediction was that the IRES removal would result in the destabilization of the NEO-trapped gene fusion transcripts because such mRNAs must be regarded by the cell as being typical NMD-prone molecules containing PTCs (Figure 4A). As shown in Figure 4B, the levels of the NEO fusion transcripts were markedly lower in the IRES-negative subclones as compared with those of the IRES-positive ones, and all of the IRES-negative subclones had lost their G418 resistance while the IRES-positive ones had not. The decrease of the NEO fusion transcripts in the IRES-negative subclones was considered to be due to the mRNA degradation by NMD because the levels of the fusion transcripts were significantly recovered after the treatment of the cells with a translation inhibitor, emetine, an efficient blocker of the NMD pathway (25) (Figure 4B). In contrast, the same treatment did not affect the amount of the fusion transcripts in the IRES-positive subclones (Figure 4B). These observations indicate that the IRES sequence inserted downstream of the NEO TC was required to prevent the fusion transcripts from undergoing NMD, and this manipulation of the mRNA-surveillance pathway in turn made it possible to trap multiple downstream exons of genes in ES cells using a novel poly-A-trap strategy.

Figure 4.

Suppression of NMD permits unbiased poly-A trapping. (A) Cre/loxP-mediated removal of the IRES sequence inserted between the NEO TC and SD sequence. (B) IRES insertion is required to suppress NMD of the NEO fusion transcripts. Two ES cell clones in which different genes (Pde9a and Nf2) had been trapped using the UPATrap vector were transiently transfected with a Cre recombinase-encoding plasmid. After isolating subclones by limiting dilution, recombination events were screened for using genomic PCR, and northern hybridization analysis of the NEO mRNAs was carried out using β-actin mRNA as an internal control. The estimated sizes of the transcripts are 3.3, 3.1 and 1.4 kb for the NEO-Pde9a fusion, the NEO-Nf2 fusion and the feeder-derived NEO, respectively. Real-time PCR was also used to evaluate the relative quantities of the NEO fusion transcripts in emetine-treated and untreated cells. The GAPDH-normalized levels of the NEO fusion transcripts are represented relative to those of the emetine-untreated IRES-positive subclones. For real-time PCR, the upstream and downstream primers were designed in the hprt-SD region of the trap vector and in the most proximal exon in the affected region of the trapped gene, respectively, in order to detect only the NEO-trapped gene fusion transcripts, neglecting the feeder-derived NEO mRNAs or endogenous mRNAs for the trapped genes. In addition, the resistance/sensitivity of the ES cell subclones to G418 (200 μg/ml) was also examined.

Although we discovered that the IRES insertion between a PTC and a downstream SD sequence suppresses NMD, the molecular mechanism responsible for this phenomenon needs to be determined. We assume that the IRES-mediated internal translation would proceed toward the end of the NEO fusion transcript, displacing the exon–exon junction complexes (EJCs) from downstream exon–exon junctions (26) (Supplementary Figure 2). The EJCs remaining attached to PTC-containing mRNAs are believed to be an essential triggering factor for NMD (11–13,27–30). Alternatively, the IRES sequence itself predicted to generate a highly complex secondary structure at the RNA level (31) might simply interfere with the interaction between components of the translation termination complex formed at a PTC and the downstream EJCs, thereby canceling the essential initial steps for NMD (27–30) (Supplementary Figure 2).

CONCLUSION

Suppression of NMD by the UPATrap strategy permits the trapping of genes (i) regardless of their transcriptional status in the target cells and (ii) without a bias in the vector-integration site. We believe this novel anti-NMD strategy enables a simple and straightforward approach to the unbiased inactivation of all mouse genes in the genome of ES cells (1). Conventional poly-A trapping, on the other hand, can be applied for more specialized purposes including the production of hypomorphic or C-terminal-tagged alleles of the disrupted genes. Combinatorial usage of the two poly-A-trap strategies (i.e. UPATrap and conventional) will significantly increase the diversity of mutations created by random intragenic vector integrations.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at NAR Online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Matsuda and R. Iida for contributing to the initial phase of this work, T. Ohnishi for helpful discussion of NMD issues, Y. Hirose for technical assistance, and A. Cowan, B. Stanger and T. Sasaoka for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research in Priority Areas ‘Genome Science’ and ‘Infection and Immunity’ from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT), Japan, to Y.I. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by MEXT, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Austin C.P., Battey J.F., Bradley A., Bucan M., Capecchi M., Collins F.S., Dove W.F., Duyk G., Dymecki S., Eppig J.T., et al. the Comprehensive Knockout Mouse Project Consortium. The Knockout Mouse Project. Nature Genet. 2004;36:921–924. doi: 10.1038/ng0904-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanford W.L., Cohn J.B., Cordes S.P. Gene-trap mutagenesis: past, present and beyond. Nature Rev. Genet. 2001;2:756–768. doi: 10.1038/35093548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gossler A., Joyner A.L., Rossant J., Skarnes W.C. Mouse embryonic stem cells and reporter constructs to detect developmentally regulated genes. Science. 1989;244:463–465. doi: 10.1126/science.2497519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansen J., Floss T., Sloun P.V., Füchtbauer E.-M., Vauti F., Arnold H.-H., Schnütgen F., Wurst W., von Melchner H., Ruiz P. A large-scale, gene-driven mutagenesis approach for the functional analysis of the mouse genome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:9918–9922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633296100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zambrowicz B.P., Abuin A., Ramirez-Solis R., Richter L.J., Piggot J., BeltrandelRio H., Buxton E.C., Edwards J., Finch R.A., Friddle C.J., et al. Wnk1 kinase deficiency lowers blood pressure in mice: a gene-trap screen to identify potential targets for therapeutic intervention. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:14109–14114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336103100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen W.V., Delrow J., Corrin P.D., Frazier J.P., Soriano P. Identification and validation of PDGF transcriptional targets by microarray-coupled gene-trap mutagenesis. Nature Genet. 2004;36:304–312. doi: 10.1038/ng1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niwa H., Araki K., Kimura S., Taniguchi S., Wakasugi S., Yamamura K. An efficient gene-trap method using poly A trap vectors and characterization of gene-trap events. J. Biochem. 1993;113:343–349. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zambrowicz B.P., Friedrich G.A., Buxton E.C., Lilleberg S.L., Person C., Sands A.T. Disruption and sequence identification of 2000 genes in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature. 1998;392:608–611. doi: 10.1038/33423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishida Y., Leder P. RET: a poly A-trap retrovirus vector for reversible disruption and expression monitoring of genes in living cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:e35. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.24.e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuda E., Shigeoka T., Iida R., Yamanaka S., Kawaichi M., Ishida Y. Expression profiling with arrays of randomly disrupted genes in mouse embryonic stem cells leads to in vivo functional analysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:4170–4174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400604101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hentze M.W., Kulozik A.E. A perfect message: RNA surveillance and nonsense-mediated decay. Cell. 1999;96:307–310. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker K.E., Parker R. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: terminating erroneous gene expression. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16:293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maquat L.E. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: splicing, translation and mRNP dynamics. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:89–99. doi: 10.1038/nrm1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duke G.M., Hoffman M.A., Palmenberg A.C. Sequence and structural elements that contribute to efficient encephalomyocarditis virus RNA translation. J. Virol. 1992;66:1602–1609. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1602-1609.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dymecki S.M. A modular set of Flp, FRT and lacZ fusion vectors for manipulating genes by site-specific recombination. Gene. 1996;171:197–201. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng C., Zhang P., Harper J.W., Elledge S.J., Leder P. Mice lacking p21CIP1/WAF1 undergo normal development, but are defective in G1 checkpoint control. Cell. 1995;82:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.You Y., Bergstrom R., Klemm M., Nelson H., Jaenisch R., Schimenti J. Utility of C57BL/6J x 129/SvJae embryonic stem cells for generating chromosomal deletions: tolerance to γ radiation and microsatellite polymorphism. Mamm. Genome. 1998;9:232–234. doi: 10.1007/s003359900731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kingston R.E., Chomczynski P., Sacchi N. Guanidine methods for total RNA preparation. In: Ausubel F.M., Brent R., Kingston R.E., Moore D.D., Seidman J.G., Smith J.A., Struhl K., editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 1987–2004. pp. 4.2.1–4.2.9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishida Y., Agata Y., Shibahara K., Honjo T. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 1992;11:3887–3895. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.To C., Epp T., Reid T., Lan Q., Yu M., Li C.Y.J., Ohishi M., Hant P., Tsao N., Casallo G., et al. The centre for modeling human disease gene trap resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D557–D559. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thermann R., Neu-Yilik G., Deters A., Frede U., Wehr K., Hagemeier C., Hentze M.W., Kulozik A.E. Binary specification of nonsense codons by splicing and cytoplasmic translation. EMBO J. 1998;17:3484–3494. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J., Sun X., Qian Y., Maquat L.E. Intron function in the nonsense-mediated decay of β-globin mRNA: indications that pre-mRNA splicing in the nucleus can influence mRNA translation in the cytoplasm. RNA. 1998;4:801–815. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298971849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu X., Li Y., Crise B., Burgess S.M. Transcriptional start regions in the human genome are favored targets for MLV integration. Science. 2003;300:1749–1751. doi: 10.1126/science.1083413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan D.C., Bedford M.T., Leder P. Formin binding proteins bear WWP/WW domains that bind proline-rich peptides and functionally resemble SH3 domains. EMBO J. 1996;15:1045–1054. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noensie E.N., Dietz H.C. A strategy for disease gene identification through nonsense-mediated mRNA decay inhibition. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:434–439. doi: 10.1038/88099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dostie J., Dreyfuss G. Translation is required to remove Y14 from mRNAs in the cytoplasm. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1060–1067. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lykke-Andersen J., Shu M., Steitz J.A. Human Upf proteins target an mRNA for nonsense-mediated decay when bound downstream of a termination codon. Cell. 2003;103:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim V.N., Kataoka N., Dreyfuss G. Role of the nonsense-mediated decay factor hUpf3 in the splicing-dependent exon–exon junction complex. Science. 2001;293:1832–1836. doi: 10.1126/science.1062829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gehring N.H., Neu-Yilik G., Schell T., Hentze M.W., Kulozik A.E. Y14 and hUpf3b form an NMD-activating complex. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:939–949. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohnishi T., Yamashita A., Kashima I., Schell T., Anders K.R., Grimson A., Hachiya T., Hentze M.W., Anderson P., Ohno S. Phosphorylation of hUPF1 induces formation of mRNA surveillance complexes containing hSMG-5 and hSMG-7. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:1187–1200. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00443-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pilipenko E.V., Blinov V.M., Chernov B.K., Dmitrieva T.M., Agol V.I. Conservation of the secondary structure elements of the 5′-untranslated region of cardio- and aphthovirus RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:5701–5711. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.14.5701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.