Abstract

Background

Thirty-day hospital readmissions are common among maintenance dialysis patients. Prior studies have evaluated easily measurable readmission risk factors such as comorbid conditions, laboratory results and hospital discharge day. We undertook this prospective study to investigate the associations of hospital-assessed depression, health literacy, social support, and self-rated health (separately) and 30-day hospital readmission among dialysis patients.

Methods

Participants were recruited from University of North Carolina (UNC) Hospitals, 2014–2016. Validated depression, health literacy, social support, and self-rated health screening instruments were administered during index hospitalizations. Multivariable logistic regression models with 30-day readmission as the dependent outcome were used to examine readmission risk factors.

Results

Of the 154 participants, 58 (37.7%) had a 30-day hospital readmission. In unadjusted analyses, individuals with positive screening for depression, lower health literacy, and poorer social support were more likely to have a 30-day readmission (vs. negative screening). Positive depression screening and poorer social support remained significantly associated with 30-day readmission in models adjusted for race, heart failure, admitting service, weekend discharge day and serum albumin: adjusted OR (95% CI), 2.33 (1.02–5.15) for positive depressive symptoms and 2.57 (1. 10–5.91) for poorer social support. The AUC of the multivariable model adjusted for social support status was significantly greater than the AUC of the multivariable model without social support status (test for equality; p-value =0.04).

Conclusion

Poor social support and depressive symptoms identified during hospitalizations may represent targetable readmission risk factors among dialysis patients. Our findings suggest that hospital-based assessments of select psychosocial factors may improve readmission risk prediction.

Keywords: psychosocial factor, depression, health literacy, social support, hospital readmission, dialysis, ESRD

INTRODUCTION

Hospitalizations and 30-day hospital readmissions among individuals receiving maintenance dialysis are frequent and costly.[1,2] A Medicare fee-for-service program study found that end stage renal disease (ESRD) patients were 40% more likely to have a 30-day hospital re-admission than non-ESRD patients.[3] Objective patient characteristics such as older age, greater illness burden and poor nutritional status are associated with higher readmission odds in this population.[2,4,5] However, other characteristics such as poor social support and emotional challenges are plausible readmission risk factors that are often not adequately assessed in retrospective (registry) analyses.

A standardized hospital readmission ratio clinical measure will enter the 2017 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Quality Incentive Program (QIP), intensifying interest in developing targeted approaches to readmission risk reduction.[6] A recent analysis demonstrated that hospital-related factors such as weekend discharge day and non-hospital-affiliated outpatient dialysis clinics are associated with increased readmission odds among maintenance hemodialysis patients.[5] Psychosocial factors were not considered. Depression, limited health literacy and poor social support have been linked to higher readmission odds in the general population.[7,8] Among individuals receiving dialysis, depression has been associated with impaired quality of life and increased morbidity and mortality.[9] Limited health literacy has been linked to treatment non-adherence and mortality[9–11]. Poor social support has been associated with reduced quality of life.(9) While individual patient psychosocial situations are often known to outpatient dialysis care team members, this information is rarely communicated to hospital providers. In-hospital screening for psychosocial risk factors may improve hospital-based readmission risk assessment and inform care setting transition planning.

Improved understanding of the influence of psychosocial factors on 30-day hospital readmission may facilitate more patient-centric approaches to readmission reduction, potentially identifying individuals appropriate for targeted hospital and outpatient case management programs. We undertook this prospective study to investigate the associations of hospital-assessed depression, health literacy, social support, and self-rated health (separately) and 30-day hospital readmission among individuals undergoing maintenance dialysis therapy who were hospitalized at a large, tertiary medical center.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design, patient population and outcome

Individuals were recruited from University of North Carolina (UNC) Hospitals (Chapel Hill, NC) between November 1, 2014 and June 30, 2016. UNC Hospitals is a public academic teaching hospital with >800 inpatient beds and >35,000 acute discharges per year. All adult individuals receiving maintenance dialysis (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) during the index hospitalization were eligible for screening. Exclusion criteria included: 1) non-English speaking, 2) delirium or altered mental status, and 3) illness severity that precluded participation in psychosocial screens, 4) dialysis-dependent acute kidney injury, and 5) prior study enrollment with completion of question battery at a previous UNC Hospitals admission. To identify eligible patients, the two study interviewers screened the hospital admission census each weekday for individuals with dialysis-dependent end-stage kidney disease and applied the selection criteria. When patients failed to meet selection criteria due to delirium or altered mental status or illness severity that precluded psychosocial participation, the interviewers, rescreened such individuals on subsequent days of the hospitalization. The index hospital admission was defined as the hospitalization when the individual was enrolled and completed the psychosocial screening battery. The primary outcome was UNC Hospitals readmission within 30 days of the index hospitalization.

This study was approved by the UNC at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board. All participating individuals provided written informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability (HIPAA) authorization for use and disclosure of health information for research purposes.

Primary exposures

The primary predictors were measures of depression, social support, health literacy and self-reported health status. Two clinicians (a single nurse practitioner (C.A.G) and a single medical student with prior training as a certified medical assistant (J.H.) verbally administered a questionnaire containing the psychosocial screens (Supplement 1). Screening instruments were selected based on their prior use in the end-stage kidney disease population. All questionnaires were administered at bedside during the hospitalization. No screens were performed during inpatient dialysis treatments. The median time [quartiles 1–3] from hospital admission to questionnaire administration was 3 [1–5] days.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale (CES-D 10) was used to assess depressive symptoms. The CES-D 10 is a 10-item questionnaire that asks respondents to rate depressive symptoms in the past week using a 4-point scale. Scores may range 0–30. Consistent with the literature, an individual with a score ≥10 was classified as meeting criteria for depressive symptoms.[9] The validity and strong psychometric properties of the CES-D have been demonstrated for individuals with a variety of chronic illnesses.[9,12,13]

The Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Survey was used to assess social support. The survey consists of 4 separate social support subscales (emotional/informational support, tangible support, affectionate support, and positive social interaction) and an overall functional social support index. Scores for each subscale are obtained by averaging the scores for each subscale item, and the overall support index is calculated from the mean of the four subscales and the score for one additional item (last item in the survey). Scores may range 0–76. Consistent with the literature, an individual with a score <57 was classified as having poor social support.[14]

The Rapid Assessment of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) was used to assess health literacy. The REALM measures a patient’s ability to pronounce 66 common medical words and lay terms for body parts and illnesses. Each participant was given a copy of the word list and was asked to read aloud as s/he could while the interviewer scored the word list. If the patient took longer than 5 seconds to read a word, the interviewer asked him/ her to move to the next word. Scores may range 0–66 based on the total number of correctly pronounced words. Higher scores indicate greater health literacy. Limited health literacy was defined as a score of ≤60 which corresponds to a reading level of less than 9th grade.[15, 16]

A single question from the Short-Form 12 (SF-12) Health Survey, “In general, would you say your health is: excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” was asked to capture self-rated general health.[17] Based on data distribution, responses were dichotomized with fair and poor responses categorized as poor self-reported health and excellent, very good and good responses categorized as good self-reported health.

Participants were allowed to omit individual questions or entire screens. Screens with omitted questions were excluded from analyses (n=19 for CES-D 10, n=28 for MOS Social Support Survey, n=34 for REALM, and n=1 for self-reported health).

Covariates

All non-psychosocial study data including demographics, co-morbid health conditions and dialysis data were extracted from the UNC Hospitals electronic medical record by a trained abstractionist. Potential covariates were selected as those variables with plausible associations with psychosocial factors or 30-day readmission based on clinical experience and literature precedent.[4,5,18]

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as means ± standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables. Bivariable comparisons across 30-day hospital readmission status were made using chi-squared tests and independent samples t tests as dictated by data type. Scores for each of the psychosocial screens were dichotomized based on instrument standards or literature precedent and examined as predictors of 30-day hospital readmission using chi-squared testing.

A multivariable binary logistic regression model with 30-day hospital readmission as the dependent outcome was constructed using variables with univariate p-values <0.10. The binary psychosocial screen variables were added, separately, to the adjusted model. Models containing multiple psychosocial screens were not considered due to collinearity among the screens. Specifically, when social support and depression screens were included in the same model with social support as the exposure, the variance inflation factor for depression was ≥2.50 (vs. =1.0 for other covariates). Separate models were thus maintained. Model goodness of fit was assessed with Hosmer and Lemeshow testing. The receiver operating characteristic curve and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) with 95% confidence intervals were derived for each model. Multivariable models with and without psychosocial screen variables were tested for equality using the DeLong et al. method for calculating the AUC standard area of the mean and the difference between model AUCs.[19] Analyses were performed using STATA 12.0MP (StataCorp., College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Characteristics of cohort

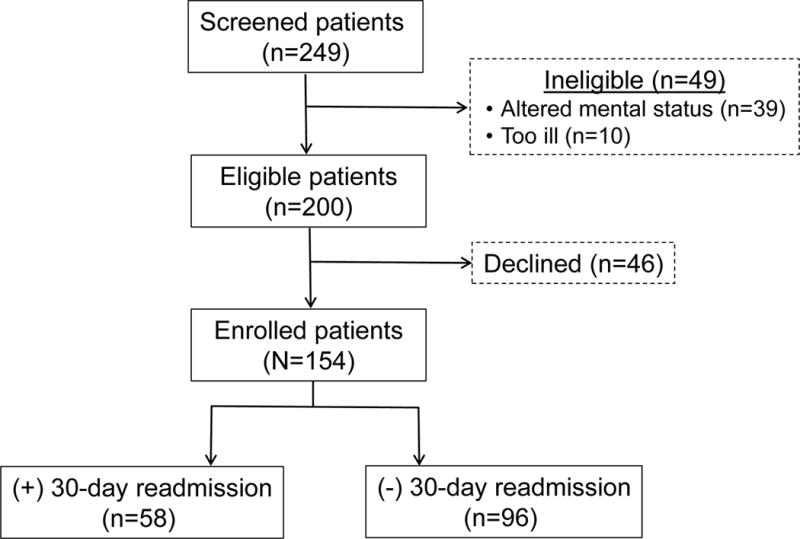

Figure 1 displays the flow diagram of study participant selection. Of the 249 patients screened, 200 met selection criteria, and, of those, 154 (77%) patients enrolled in the study. Participant characteristics at index hospitalization across 30-day readmission status are displayed in Table 1. Of the 154 participants, 67 (43.5%) were women, the mean age was 59 ± 15 years, and 70 (45.4%) were black. Approximately half (48.0%) dialyzed at UNC-affiliated outpatient dialysis clinics, 18 (11.7%) received peritoneal dialysis, and 50 (32.5%) had a dialysis vintage <1 year. The principal index admission diagnosis was cardiovascular-related in 48 (31.2%) patients and infection-related in 19 (12.3%) patients. The median [quartiles 1–3] length of index hospitalization was 5 [3–9] days.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study participant selection.

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics by 30-day readmission status.

| Characteristic | Overall (N=154) | (+) 30-day readmission (n=58, 37.7%) | (−) 30-day readmission (n=96, 62.3%) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | 59 ± 15 | 61 ± 15 | 57 ± 14 | 0.6 |

|

| ||||

| Female | 67 (43.5%) | 27 (46.6%) | 40 (41.7%) | 0.5 |

|

| ||||

| Black | 70 (45.4%) | 33 (56.9%) | 37 (38.5%) | 0.03 |

|

| ||||

| Diabetes | 72 (46.7%) | 25 (43.1%) | 47 (49.0%) | 0.5 |

|

| ||||

| Heart failure | 44 (28.6%) | 24 (41.4%) | 20 (20.8%) | 0.04 |

|

| ||||

| Arterial diseaseb | 83 (53.9%) | 31 (53.4%) | 52 (54.2%) | 0.9 |

|

| ||||

| Malignancy | 36 (23.4%) | 15 (25.9%) | 21 (21.9%) | 0.6 |

|

| ||||

| Mental health disorder | 38 (24.7%) | 16 (27.6%) | 22 (22.9%) | 0.5 |

|

| ||||

| Outpatient medications ≥10 | 99 (64.7%) (n=153) |

38 (66.7%) (n=57) |

61 (63.5%) | 0.7 |

|

| ||||

| Surgery admitting service | 38 (24.7%) | 10 (17.2%) | 28 (29.2%) | 0.09 |

|

| ||||

| Dialysis vintage <1 year | 50 (32.9%) (n=152) |

19 (32.8%) | 31 (33.0%) (n=94) |

0.9 |

|

| ||||

| Peritoneal dialysis | 18 (11.7%) | 6 (10.3%) | 12 (12.5%) | 0.7 |

|

| ||||

| HD vascular access | 0.8 | |||

| Fistula | 63 (46.3%) | 26 (50.0%) | 37 (44.0%) | |

| Graft | 20 (14.7%) | 7 (13.5%) | 13 (15.5%) | |

| Catheter | 53 (39.0%) (n=136)c | 19 (36.5%) (n=52) | 34 (40.5%) (n=84) | |

|

| ||||

| Non-UNC-affiliated outpatient dialysis facility | 80 (52.0%) | 26 (44.8%) | 54 (56.3%) | 0.2 |

|

| ||||

| Primary admission diagnosis | 0.2 | |||

| Cardiovascular | 48 (31.2%) | 14 (24.1%) | 34 (35.4%) | |

| Infection | 19 (12.3%) | 7 (12.1%) | 12 (12.5%) | |

| Vascular access (non-infectious)d | 17 (11.0%) | 10 (17.2%) | 7 (7.3%) | |

| Abdominal pain or gastrointestinal bleed | 33 (21.4%) | 12 (20.7%) | 21 (21.9%) | |

| Surgerye | 16 (10.4%) | 8 (13.8%) | 8 (8.3%) | |

| Other | 21 (13.7%) | 7 (12.1%) | 14 (14.6%) | |

|

| ||||

| Albumin <3.3 g/dL | 65 (42.2%) | 36 (62.1%) | 29 (30.2%) | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 7.2 ± 10.24 | 6.0 ± 5.2 | 8.0 ± 12.6 | 0.1 |

|

| ||||

| Discharged to nursing facilityd | 13 (8.6%) (n=152) | 4 (6.9%) (n=58) | 9 (9.6%) (n=94) | 0.6 |

|

| ||||

| Weekend discharge day | 19 (12.3%) | 12 (20.7%) | 7 (7.3%) | 0.01 |

Significance was assessed by x2- tests or independent samples t-tests depending on data distribution.

Includes ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease.

Represents complete vascular access type data on the 136 individuals receiving hemodialysis. The remaining 18 individuals received peritoneal dialysis.

Admission for a vascular access procedure with no evidence of infection. Vascular access admissions with noted vascular access infection (e.g. abscess, catheter-related bacteremia) were classified as infection-related admissions.

Admission for surgical procedure (excluding vascular access procedure). Examples include: nephrectomy, parathyroidectomy and knee replacement.

Nursing facility includes skilled nursing facilities, rehabilitation facilities, and long-term care facilities. Other includes home with family or friends or to a temporary housing location.

Of the 135 participants completing depression screening, 79 (58.5%) had a positive depression screen (CES-D-10 >10). Patients with a positive depression screen were more likely to have heart failure than those with a negative screen (p-value =0.04). Of the 120 participants completing health literacy screening, 52 (43.3%) displayed limited health literacy (REALM ≤60). Participants with limited health literacy were younger and more likely to be male and black compared to those with adequate health literacy (p-values <0.05 for all). Of the 126 participants completing social support screening, 38 (30.2%) had poor social support (MOS <57). Participants with poor social support were younger, more likely to be male, black and have a psychiatric co-morbid diagnosis compared to those with adequate social support (p-values <0.05 for all). Of the 153 participants reporting self-health, 54 (35.3%) reported fair or poor health. Participants self-reporting fair or poor health were younger, more likely to be male, white and have a psychiatric co-morbid diagnosis compared to those reporting good, very good or excellent health (p-values <0.05 for all).

Hospital Readmissions

Of the 154 participants, 58 (37.7%) had a 30-day hospital readmission. Among those with a 30-day readmission, the mean time to readmission was 12.6 ± 8.0 days. Seven (12.1%) patients with 30-day readmissions were readmitted within 3 days of index hospital discharge. Patients with 30-day readmission were more likely to be black, discharged on a weekend day, have heart failure, and have an albumin <3.3 g/dL (p-values <0.05 for all).

In the adjusted logistic regression model for 30-day readmission considering variables with univariate p-values<0.10 (without psychosocial variables), black race (odds ratio [OR], 2.11; 95% CI, 1.04 to 4.26), heart failure (OR, 1.89, 95% CI, 1.01–5.12), weekend discharge day (OR, 3.79; 95% CI, 1.33–10.79), and albumin <3.3 g/dL (OR, 4.20, 95% CI (1.48–12.71) were associated with higher readmission odds. Surgical service admission (OR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.19–1.06) was associated with lower readmission odds, but the association did not reach statistical significance.

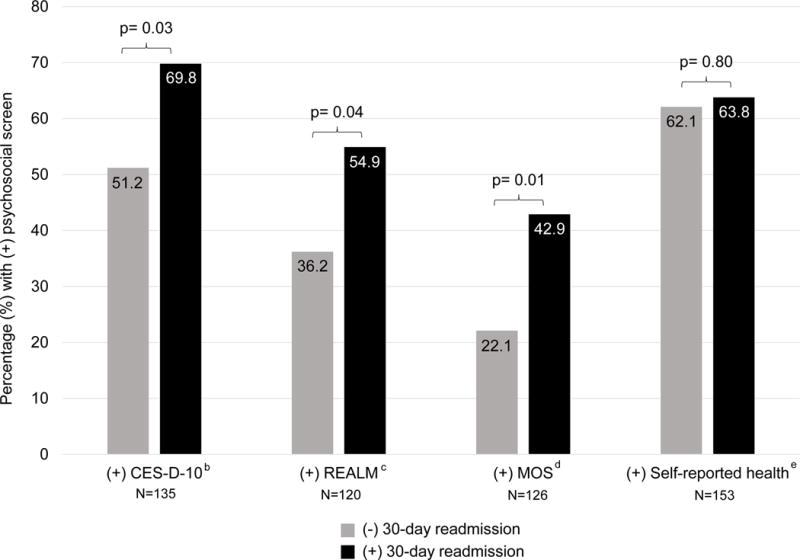

Psychosocial factors and 30-day hospital readmission

Figure 2 displays psychosocial screen results across 30-day hospital admission status. In unadjusted analyses, individuals with positive depression screening, lower health literacy, and poorer social support were more likely to have a 30-day readmission (vs. those with negative screens). Table 2 displays adjusted associations between psychosocial factors and 30-day readmission. In models adjusted for race, heart failure, admitting service, weekend discharge day, and albumin, poorer social support (OR, 2.57, 95% CI, 1.10–5.91) was significantly associated with higher readmission odds. Model performance as characterized by the AUC was moderate: 0.75 (95% CI, 0.64–0.82). Consideration of social support status in the multivariable model improved model performance. The AUC of the multivariable model adjusted for social support status was significantly greater than the AUC of the multivariable model without social support status (test for equality; p=0.04).

Figure 2. Positive psychosocial screen results across 30-day hospital readmission statusa.

aSignificance was assessed by x2-testing. N values represent total number of participants completing the specified psychosocial screen.

b(+) CES-D-10 defined as CES-D-10 score ≥10.

c(+) REALM defined as REALM score ≤60.

d(+) MOS defined as MOS score <57.

e(+) Self-reported health defined as self-reported health status of poor or fair.

Table 2.

Adjusted associations between psychosocial factors and 30-day hospital readmission.

| Psychosocial screen | N | (+) Psychosocial screen result adjusted OR (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) |

Test for equality pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1b | 154 | — | 0.69 (0.61–0.79) |

— |

| Model 1 + CES-Dc (+ depressive symptoms) |

135 | 2.33 (1.02–5.15) | 0.72 (0.61–0.83) |

0.07 |

| Model 1 + REALMd (Limited health literacy) |

120 | 2.20 (0.99–4.97) | 0.71 (0.61–0.82) |

0.19 |

| Model 1 + MOSe (Poor social support) |

126 | 2.57 (1.10–5.91) | 0.75 (0.64–0.84) |

0.04 |

| Model 1 + Self-reported healthf (Poor self-reported health) |

153 | 1.04 (0.53–2.19) | 0.69 (0.60–0.79) |

0.89 |

Psychosocial adjusted models (separately) and Model 1 AUCs were tested for equality using the method by DeLong et al.[20] for calculating the AUC standard error of the mean and the difference between model AUCs.

Multivariable logistic model adjusted for race (black or nonblack), heart failure, admitting service (surgical vs. non-surgical), discharge day (weekend vs. non-weekend), and serum albumin (<3.3 vs. ≥3.3 g/dL).

Multivariable logistic model adjusted for depression (CES-D 10 ≥10 vs. <10), race (black or nonblack), heart failure, admitting service (surgical vs. non-surgical), discharge day (weekend vs. non-weekend), and serum albumin (<3.3 vs. ≥3.3 g/dL).

Multivariable logistic model adjusted for health literacy (REALM ≤60 vs. >60), race (black or nonblack), heart failure, admitting service (surgical vs. non-surgical), discharge day (weekend vs. non-weekend), and serum albumin (<3.3 vs. ≥3.3 g/dL).

Multivariable logistic model adjusted for social support (MOS <57 vs. ≥57), race (black or nonblack), heart failure, admitting service (surgical vs. non-surgical), discharge day (weekend vs. non-weekend), and serum albumin (<3.3 vs. ≥3.3 g/dL).

Multivariable logistic model adjusted for self-reported health status (poor/fair vs. good/very good/excellent), race (black or nonblack), heart failure, admitting service (surgical vs. non-surgical), discharge day (weekend vs. non-weekend), and serum albumin (<3.3 vs. ≥3.3 g/dL).

Positive depression screening was also significantly associated with higher 30-day hospital readmission odds after multivariable model adjustment: OR, 2.33 (95% CI, 1.025.15). The AUC of the multivariable model adjusted for depression was not significantly different from the AUC of the multivariable model without depression (test for quality; p=0.07). Lower health literacy trended toward an association with higher readmission odds in multivariable models, but did not reach statistical significance. Self-reported health status was not associated with readmission.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study evaluating hospital-identified psychosocial risk factors for 30-day hospital readmission among maintenance dialysis patients. Our single-center analysis demonstrated that poor social support and the presence of depressive symptoms were each associated with higher 30-day readmission odds. Impaired health literacy trended toward an association with higher 30-day readmission odds, but did not achieve statistical significance in adjusted models. The adjusted model containing social support status was more predictive of readmission than the adjusted model without social support status. Our results suggest that transition programs targeting patients with poorer social support and depressive symptoms may represent opportunities for hospital readmission risk reduction among individuals receiving dialysis.

Depression, poor social support and limited health literacy may affect an individual’s ability to understand and carry out hospital discharge instructions and follow-up plans, plausibly increasing readmission risk. Depression is almost four-times more common among ESRD patients compared to the general population and is associated with missed dialysis treatments, reduced quality of life, and increased morbidity and mortality.[9,20] Adequacy of individual social support networks can influence depressive symptoms and health behaviors.[10] Limited social support has been linked to poor treatment adherence and worse quality of life among dialysis patients.[10] Health literacy, the capacity to understand information related to disease in order to make informed decisions, may also influence a patient’s post-hospitalization course.[16] Limited health literacy is suspected in close to a third of dialysis patients and is independently associated with missed dialysis treatments, higher emergency room utilization and greater mortality.[11,21] While some of these psychosocial risk factors may be detected by the Kidney Disease Quality of Life Scale (KDQoL) or other routine outpatient screens, such data are not typically available to hospital providers.

Past efforts to understand readmission risk factors among individuals receiving maintenance dialysis have focused on objective patient factors such as co-morbid conditions and laboratory values as well as provider-centric factors such as discharge day and hospital follow-up practices.[4,5,22] Unfortunately, 30-day hospital readmission rates among maintenance dialysis patients remain high.[1] More patient-centric approaches that consider inadequate education or social and emotional barriers to care may offer new opportunities for readmission risk reduction. For example, patient understanding of discharge instructions and medications and their general abilities to manage their affairs and recover from their hospitalizations may impact readmission risk.[23–25] To assess these potential risks, a more detailed understanding of patient psychosocial risk factors is needed during the hospital stay.

We evaluated the influence of hospital-identified depressive symptoms, limited health literacy, reduced social support and poorer self-rated health on 30-day hospital readmissions. Our study cohort’s 30-day readmission rate of 37.7% was slightly above the national rate of 32.1%.[1] This finding, in combination with the observed longer lengths of stay (7.2 ± 10.2 days), suggest that our study participants may have had greater medical acuity compared to the broader hemodialysis population. Our results should be interpreted with this in mind. In unadjusted analyses, greater depressive symptoms, limited health literacy and reduced social support were associated with increased readmission odds. After adjustment for potential confounders, reduced social support had the greatest readmission predictive capacity. Greater depressive symptoms also associated with increased readmission odds in adjusted analyses. Health literacy and self-rated health status did not associate with readmission in adjusted models.

While the associations of psychosocial factors and hospital readmission identified in this study do not imply causation, they do suggest that formalized screens of social support, and depression may enhance risk estimation associated with hospital to home transitions and, in turn, may facilitate more focused discharge planning. Future efforts to improve transitions may benefit from increased focus on patient self-management and social support. In fact, a recent systematic review in the general population suggested that readmission prevention programs focused on patient capacity for self-care with more comprehensive post-hospital discharge support were more effective than programs without these support strategies.[26] For example, enhanced psychosocial data would enable in-hospital case management programs to realign resources toward behavioral counseling and education in appropriate patients. Such risk factors are difficult to modify in time-limited periods like hospitalizations, but enhanced discharge planning and communication with outpatient dialysis clinics would allow for ongoing follow-up of these issues post-hospital discharge, potentially reducing readmission risk.

Ideally, outpatient dialysis clinic medical information, dialysis treatment prescriptions, and relevant psychosocial data would be transmitted to the hospital at the time of admission. However, in our fragmented care environment where hospital and outpatient dialysis electronic health records do not communicate and we increasingly rely on hospital-based specialists for inpatient care delivery, transfer of important medical information often falls short. In a recent analysis, we reported that hospital discharge on a weekend day (vs. week day) was associated with increased odds of hospital readmission,[5] suggesting that inadequate communication related to reduced case management services and weekend transitional care providers may contribute to readmission risk. A recent systematic review of the outpatient to inpatient transfer process in the general population revealed low frequency of direct communication between providers at the time of admission. The authors also found that when communication did occur, the communication was most often telephone-based, potentially limiting the amount of data transferred.[27] Thus, until electronic health record data sharing improves, it may be reasonable to consider screening for select risk factors such as psychosocial barriers during hospitalizations.

Hospital-based psychosocial risk assessment would require efficient, validated screening instruments as well as designated team members to routinely perform the screens in busy inpatient environments. In our study, we used the 10-item CES-D 10 instrument for depression and the 19-item MOS Social Support Survey instrument for social support. While the CES-D 10 can be administered quickly, the MOS Social Support Survey instrument is more burdensome, as evidenced by a higher proportion of participants omitting questions or skipping the screen (19 for CES-D 10 vs. 28 for MOS Social Support Survey). To reduce burden, shorter social support assessment instruments such as the KDQOL social support questions could be considered. Additionally, further evaluation of the optimal timing of psychosocial screening (admission vs. discharge) is needed as is the development of transition programs with greater emphasis on social risk factor understanding and modification.

Strengths of our study include its prospective nature, use of validated screening instruments and systematic approach to screening unique hospitalized dialysis patients at UNC Hospitals. However, our findings must be considered in the context of study limitations. First, this is a single-center study. Our geographic catchment area has a high proportion of blacks and >50% receive outpatient dialysis at university-associated dialysis clinics. Our hospital and associated dialysis unit clinical protocols may differ from those of other systems, and our results may not generalize to other centers. Second, our sample size was modest, limiting the number of predictors we could assess in multivariable models. Some eligible individuals for the study may have been missed in the recruitment process due to short hospitalizations or missed contact due to hospital procedures exists. Confounding from unmeasured factors or factors not considered in the limited models may remain. Verification of our findings in a larger cohort is needed. Third, some participants had incomplete screening instrument data. Individuals with incomplete screening data were excluded from analyses considering the missing screening data. Related, we lacked covariate data (outpatient medications, n=1; dialysis vintage, n=2; discharge to nursing facility, n=2) on a few patients. However, covariate missingness was minimal and not present among covariates meeting multivariable model inclusion criteria. Fourth, our observed readmission rate (37.7%) is higher than the national average rate of 32.1% among end-stage kidney disease patients. Our cohort may have had greater illness acuity. Our findings should be confirmed in a larger population. Finally, we were unable to consider readmissions that occurred outside of our hospital network.

In conclusion, we evaluated hospital-assessed psychosocial risk factors for 30-day hospital readmission among patients on maintenance dialysis and identified poorer social support and depressive symptoms as potential targetable risk factors for readmission. Our findings suggest that hospital-based assessments of select psychosocial factors may help identify vulnerable patient subgroups to whom to direct targeted discharge services. Pilot studies evaluating in-hospital psychosocial screens and associated individualized discharge planning services are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES

Dr. Flythe is supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institute of Health Grant K23 DK109401.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Flythe has received speaking honoraria from Dialysis Clinic, Incorporated, Renal Ventures, American Renal Associates, American Society of Nephrology, multiple universities, and Baxter and research funding for studies unrelated to this project from the Renal Research Institute, a subsidiary of Fresenius Medical Care, North America.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System. 2013 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathew AT, Strippoli GF, Ruospo M, Fishbane S. Reducing hospital readmissions in patients with end-stage kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2015;88:1250–1260. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan KE, Lazarus JM, Wingard RL, Hakim RM. Association between repeat hospitalization and early intervention in dialysis patients following hospital discharge. Kidney Int. 2009;76:331–341. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flythe JE, Katsanos SL, Hu Y, Kshirsagar AV, Falk RJ, Moore CR. Predictors of 30-Day Hospital Readmission among Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients: A Hospital’s Perspective. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:1005–1014. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11611115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ESRD QIP Summary: Payment Years 2014 – 2018. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/ESRDQIP/Downloads/ESRDQIPSummaryPaymentYears2014–2018.pdf. Accessed November 29, 2016.

- 7.Arozullah AM, Lee SY, Khan T, Kurup S, Ryan J, Bonner M, Soltysik R, Yarnold PR. The roles of low literacy and social support in predicting the preventability of hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:140–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pederson JL, Warkentin LM, Majumdar SR, McAlister FA. Depressive symptoms are associated with higher rates of readmission or mortality after medical hospitalization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:373–380. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopes AA, Albert JM, Young EW, Satayathum S, Pisoni RL, Andreucci VE, Mapes DL, Mason NA, Fukuhara S, Wikstrom B, Saito A, Port FK. Screening for depression in hemodialysis patients: associations with diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes in the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2004;66:2047–2053. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Untas A, Thumma J, Rascle N, Rayner H, Mapes D, Lopes AA, Fukuhara S, Akizawa T, Morgenstern H, Robinson BM, Pisoni RL, Combe C. The associations of social support and other psychosocial factors with mortality and quality of life in the dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:142–152. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02340310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green JA, Mor MK, Shields AM, Sevick MA, Arnold RM, Palevsky PM, Fine MJ, Weisbord SD. Associations of health literacy with dialysis adherence and health resource utilization in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:73–80. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, Prusoff BA, Locke BZ. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;106:203–214. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts RE. Reliability of the CES-D Scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Res. 1980;2:125–134. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salinero-Fort M, del Otero-Sanz L, Martin-Madrazo C, de Burgos-Lunar C, Chico-Moraleja RM, Rodés-Soldevila B, Jiménez-Garcia R, Gomez-Campelo P, Group HM The relationship between social support and self-reported health status in immigrants: an adjusted analysis in the Madrid Cross Sectional Study. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis TC, Crouch MA, Long SW, Jackson RH, Bates P, George RB, Bairnsfather LE. Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients. Fam Med. 1991;23:433–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain D, Green JA. Health literacy in kidney disease: Review of the literature and implications for clinical practice. World J Nephrol. 2016;5:147–151. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v5.i2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harel Z, Wald R, McArthur E, Chertow GM, Harel S, Gruneir A, Fischer HD, Garg AX, Perl J, Nash DM, Silver S, Bell CM. Rehospitalizations and Emergency Department Visits after Hospital Discharge in Patients Receiving Maintenance Hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014060614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer S, Vecchio M, Craig JC, Tonelli M, Johnson DW, Nicolucci A, Pellegrini F, Saglimbene V, Logroscino G, Fishbane S, Strippoli GF. Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int. 2013;84:179–191. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cavanaugh KL, Wingard RL, Hakim RM, Eden S, Shintani A, Wallston KA, Huizinga MM, Elasy TA, Rothman RL, Ikizler TA. Low health literacy associates with increased mortality in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1979–1985. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009111163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erickson KF, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J. Physician visits and 30-day hospital readmissions in patients receiving hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2079–2087. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makaryus AN, Friedman EA. Patients’ understanding of their treatment plans and diagnosis at discharge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:991–994. doi: 10.4065/80.8.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maniaci MJ, Heckman MG, Dawson NL. Functional health literacy and understanding of medications at discharge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:554–558. doi: 10.4065/83.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greysen SR, Hoi-Cheung D, Garcia V, Kessell E, Sarkar U, Goldman L, Schneidermann M, Critchfield J, Pierluissi E, Kushel M. “Missing pieces”–functional, social, and environmental barriers to recovery for vulnerable older adults transitioning from hospital to home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1556–1561. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, Brito JP, Mair FS, Gallacher K, Wang Z, Erwin PJ, Sylvester T, Boehmer K, Ting HH, Murad MH, Shippee ND, Montori VM. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1095–1107. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luu NP, Pitts S, Petty B, Sawyer MD, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Boonyasai RT, Maruthur NM. Provider-to-Provider Communication during Transitions of Care from Outpatient to Acute Care: A Systematic Review. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:417–425. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3547-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.