ABSTRACT

Life-threatening infection in neonates due to group B Streptococcus (GBS) is preventable by screening of near-term pregnant women and treatment at delivery. A total of 295 vaginal-rectal swabs were collected from women attending antepartum clinics in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. GBS colonization was detected by the standard culture method (Strep B Carrot Broth subcultured to blood agar with a neomycin disk) and compared to recovery with Strep Group B Broth (Dalynn Biologicals) subcultured to StrepBSelect chromogenic medium (CM; Bio-Rad Laboratories) and the Fast-Track Diagnostics GBS real-time PCR (quantitative PCR [qPCR]) assay (Phoenix Airmid Biomedical Corp.) performed with broth-enriched samples and the Abbott m2000sp/m2000rt system. A total of 62/295 (21%) women were colonized with GBS; 58 (19.7%) cases were detected by standard culture, while CM and qPCR each found 61 (20.7%) cases. The qPCR and CM were similar in performance, with sensitivities, specificities, and positive and negative predictive values of 98.4 and 98.4%, 99.6 and 99.6%, 98.4 and 98.4%, and 99.6 and 99.6%, respectively, compared to routine culture. Both qPCR and CM would allow more rapid reporting of routine GBS screening results than standard culture. Although the cost per test was similar for standard culture and CM, the routine use of qPCR would cost approximately four times as much as culture-based detection. Laboratories worldwide should consider implementing one of the newer methods for primary GBS testing, depending on the cost limitations of different health care jurisdictions.

KEYWORDS: chromogenic medium, detection, group B streptococcus, real-time PCR, screening

INTRODUCTION

Group B streptococcus (GBS) is the most common cause of early-onset neonatal sepsis in developed countries (1, 2). Early-onset disease (0 to 6 days of life) is acquired intrapartum from mothers with vaginal-rectal colonization with GBS (1–3). Maternal GBS colonization rates range from approximately 10 to 40% in developed countries, with an estimated rate of 20% in near-term pregnant women in our health care region (2, 4, 5). Studies have shown that intrapartum administration of antibiotics reduces neonatal transmission of GBS, thereby preventing early-onset disease (1, 6, 7). Laboratory detection of GBS colonization status in near-term pregnant women is therefore important for the selective prescription of antibiotic prophylaxis at delivery.

Guidelines for the prevention of early-onset neonatal GBS disease have previously been published that recommend universal prenatal culture-based screening of all pregnant women for vaginal-rectal colonization at 35 to 37 weeks of gestation (or earlier if membrane rupture occurs), with intrapartum chemoprophylaxis offered to the carriers (8). Our centralized regional laboratory uses StrepB Carrot Broth (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Clara, CA) for vaginal-rectal swab GBS culture because we have previously documented that it had performance similar to that of Lim broth but more rapidly detected and differentiated GBS because of the production of an orange-red pigment (i.e., 24 h) (9). Approximately 80% of GBS results can be reported after 24 h of incubation with Strep Carrot Broth (SCB), while subculture is required to detect the remaining positive cases (9). Routine culture methods, however, have a significantly longer turnaround time because a final result is not available until 72 to 96 h after the receipt of a vaginal-rectal sample. To accelerate the overall diagnostic process for GBS screening and detection, our laboratory compared the use of chromogenic GBS agar and a high-volume commercial real-time PCR as potential replacements for the standard culture method after an initial broth enrichment.

StrepBSelect is a newly developed, defined chromogenic medium for the detection of GBS isolates. Unlike traditional, nonchromogenic agars, this chromogenic medium (CM) does not rely on anaerobiosis and has been designed to detect non-beta-hemolytic GBS more easily. The use of a highly sensitive CM would potentially shorten the time to a result by a day because GBS isolates would be directly identified without having to perform additional phenotypic tests. Because of the high number of samples tested per annum in our laboratory (∼18,000), we selected the Fast-Track GBS PCR assay because its 96-well plate format would provide the necessary test throughput and its performance had been preverified by the manufacturer for performance on the Abbott m2000sp/m2000rt system already available in our laboratory. This study therefore compared the broth-enriched CM and commercial quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay to our routine Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-compliant culture method to verify not only their performance but also the operational efficiency of each of these methods for accelerating the reporting of results.

RESULTS

A total of 295 pregnant women who were between 35 and 37 weeks of gestation were enrolled from a single large maternity clinic in our region. Overall, 62 (21%) women were confirmed to be colonized by GBS by two or more test methods. Fifty-eight (19.5%) women were colonized by GBS according to an initial positive standard SCB culture, but another four cases were detected by the other methods; two other cases were detected by both CM and qPCR, and one case was detected by qPCR alone. All three of these SCB culture-negative cases were also confirmed by the second qPCR method. One other case was detected only by CM and confirmed by the secondary qPCR (Abbott IMDx) but not by either routine culture or the initial qPCR (Fast-Track Diagnostics GBS). The latter result was considered a false negative by both routine culture and the initial qPCR test.

Our standard culture method had the longest overall turnaround time. Although a positive SCB result can be reported as GBS within 24 h, it takes a total of 72 to 96 h to report a final result from the subculture. The use of an initial broth enrichment, followed by either CM culture method or qPCR, would substantially decrease the overall test turnaround time. All CM subcultures were reported within 48 h, while qPCR could be completed within 36 h after swab receipt.

Table 1 shows the performance of both culture methods and qPCR according to the modified “gold standard” (see Materials and Methods). Both CM and qPCR had the same performance; both methods detected 4.9% more cases of GBS genital colonization than the routine culture methods and also had similar specificities, positive predictive values (PPVs), and negative predictive values (NPVs). Routine culture, while being highly specific, missed GBS detection in 4/62 (6.5%) true positive cases.

TABLE 1.

Performance of various GBS detection methods compared to that of the combined gold standarda

| Performance | No. of samples positive/total (%/95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| SCB culture | CM | qPCR assay | |

| Sensitivity | 58/62 (93.5/0.835–0.979) | 61/62 (98.4/0.901–0.999) | 61/62 (98.4/0.901–0.999) |

| Specificity | 233/233 (100/0.979–1.0) | 232/233 (99.6/0.972–0.999) | 232/233 (99.6/0.972–0.999) |

| PPV | 58/58 (100/0.922–1.0) | 61/62 (98.4/0.901–0.999) | 61/62 (98.4/0.901–0.999) |

| NPV | 233/237 (98.3/0.954–0.994) | 232/233 (99.6/0.972–0.999) | 232/233 (99.6/0.972–0.999) |

A true positive result is GBS detection by routine and/or CM culture and confirmation by either molecular method.

The component costs of implementing either CM or the qPCR method are compared to those of routine culture in Table 2. Although the molecular method had performance similar to that of CM, it would be much more expensive to use as the primary method in our laboratory jurisdiction. Universal molecular analysis is projected to increase annual operating costs approximately $359,653.32, even though it would save an estimated 0.07 full-time equivalent (FTE) because culture would only have to be performed to provide an antibiotic susceptibility result for GBS-positive patients with a reported history of penicillin allergy. In comparison, implementation of CM as the routine culture method would result in overall net savings of $5,541.12 per annum and would free up an estimated 0.12 FTE to perform other duties. Although CM has a cost per test similar to that of routine culture, the routine use of qPCR in our health care jurisdiction would result in a cost per test approximately four times that of a culture-based method.

TABLE 2.

Annual cost of using CM or Fast-Track Diagnostics qPCR assay compared to routine culturea

| Cost | Routine culture | CM | Difference from routine culture (%) | qPCR assay | Difference from routine culture (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labor | 4.44 | 3.96 | ↓0.48 (10.8) | 3.97 | ↓0.47 (10.6) |

| Per test | 7.20 | 6.88 | ↓0.32 (4.4) | 27.97 | ↑20.7 (287.5) |

| Monthly | 10,389.60 | 9,927.84 | ↓461.76 | 40,360.71 | ↑29,971.1 |

| Annual | 124,675.20 | 119,134.08 | ↓5,541.1 (4.4) | 484,328.52 | ↑359,653.32 (287.5) |

All costs were calculated in Canadian dollars and are based on a total test volume of 1,443 vaginal-rectal samples per month according to the CLS workload in 2015. The cost per test of all methods includes an initial broth enrichment step.

DISCUSSION

Our study is one of only a few reports to evaluate the use of CM for detection of GBS colonization in antepartum women. Further, this is the first reported head-to-head comparison of the 96-well plate format Fast-Track Diagnostics GBS qPCR assay run on a high-volume instrument platform. Our results confirm previous reports of the lower sensitivity of routine culture than either of these newer methods (10–20). Overall, CDC-compliant nonchromogenic culture medium procedures for genital GBS detection had a sensitivity 3 to 5% lower than that of CM cultures or qPCR. The abilities of various GBS CMs reportedly vary depending on the commercial supplier and whether or not the vaginal-rectal swab is inoculated directly or after broth enrichment (i.e., Lim broth, Todd-Hewitt broth, or SCB) (16–20). Craven et al. compared the yield of ChromID Strepto B agar (bioMérieux, Inc.) with that of routine culture with Lim broth and neomycin-nalidixic acid agar (NNA) for detection of GBS in 250 prenatal screening swabs (17). Although CM was more sensitive (87.7%) than NNA alone (79%) without pre-enrichment, Lim broth enrichment prior to inoculation of either chromogenic or routine culture medium increased the sensitivity of both methods to 100%. Poisson et al. similarly showed improved GBS detection in 285 vaginal-rectal swabs collected from prepartum women by inoculation of ChromID Strepto B agar after Todd-Hewitt broth enrichment compared to the use of two routine culture media (i.e., blood agar and colimycin-nalidixic acid agar) (18). However, another recent study of GBS culture methods by El Aila et al. for prenatal screening of 100 pregnant women near term found that direct plating of rectovaginal swabs onto ChromID Strepto B agar was more sensitive (95%) than direct Granada medium culture (91%) or Lim broth enrichment and subculture onto Columbia CAN agar (77%) (19). Salem and Anderson evaluated four chromogenic media for genital GBS detection in 242 pregnant women compared with the conventional pre-enrichment CDC culture method (20). The sensitivity and specificity of direct CM culture were 92 and 100% for StrepBSelect (Bio-Rad laboratories), 96 and 100% for Brilliance GBS (Thermo-Fisher Scientific), 94 and 100% for CM StrepB (Dutec Diagnostics), and 86 and 100% for ChromID Strepto B agar compared to 90 and 100% for routine CDC culture (20).

A pre-enrichment step also improves the detection of GBS prior to molecular testing, although few other studies to date have simultaneously compared the abilities of CM and real-time PCR with or without prior broth enrichment to detect genital GBS in antepartum women. El Aila et al. compared chromID Strepto B culture and prior Lim broth enrichment with two qPCR assays (i.e., the hydrolysis probe format (TaqMan; Roche) targeting the sip gene and the hybridization probe format (Hybprobe; Roche) targeting the cfb gene) performed directly with a rectovaginal ESwab or with a Lim broth enrichment culture (21). Of the 100 pregnant women tested in that study, 33% were GBS positive according to the pre-enrichment CM culture, and qPCR also detected all of these cases except one. Performance of qPCR directly with rectovaginal samples missed 3% of the cases that were detected by using pre-enrichment prior to either CM culture or qPCR, although the bacterial inoculum size was small for these women. Berg et al. compared five different methods of genital GBS detection that included three culture-based methods, including chromogenic culture with Northeast Laboratory GBS agar (Northeast Laboratory Services, Winslow, ME), carrot broth-enhanced subculture to GBS Detect (Hardy Diagnostics), and carrot broth- and Lim broth-enhanced real-time PCRs, as well as routine Strep B Carrot Broth culture (22). Carrot broth-enhanced subculture to GBS Direct chromogenic medium had performance comparable to that of broth-enhanced qPCR, and either method had a higher sensitivity than routine culture.

Our study shows that broth-enriched StrepBSelect CM had performance similar to that of broth-enriched qPCR for the enhanced recovery of GBS from vaginal-rectal swabs collected antepartum from women near term. These data confirm and enhance the findings of other investigators but provide further diagnostic evidence that routine use of pre-enrichment broth followed by subculture onto CM or subsequent detection by commercial qPCR would improve the overall detection of genital GBS colonization. Direct qPCR from vaginal-rectal swabs has previously been shown to have performance similar to that of standard culture in that 6% of GBS cases are missed (19). One drawback of using a molecular method for primary GBS detection in all patients is loss of the ability to subculture GBS isolates in positive women for antibiotic susceptibility testing. GBS-positive samples detected by qPCR would also have to be subcultured to perform antibiotic susceptibility testing because of the increased resistance documented in our region (23). Another potential limitation of the routine use of qPCR in Canadian health care jurisdictions that operate on fixed budgets is the substantially higher overall cost per test than that of a culture-based method for routine genital GBS detection. A substantial increase in our laboratory funding from our single-payer system is required to fully implement qPCR for routine testing of GBS detection in near-term pregnant women. Laboratories in the United States that receive reimbursement for testing may not face these financial restrictions. Our group and others have shown, however, that use of the GBS GeneXpert qPCR assay (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA) for rapid determination of GBS colonization status (<4 h) is required in our region because 6% of women present without having had prior screening (10). Clinical laboratories should consider implementing one of the newer methods for primary GBS testing, depending on the cost limitations of individual health care jurisdictions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pregnant women near term (i.e., between 35 and 37 weeks of gestation) were enrolled from a single large maternity clinic in our region (Sunridge Maternity Care Clinic, Calgary, Alberta, Canada) and screened for GBS colonization in accordance with the clinic's routine protocol. All of the women were informed by their physicians that additional testing to detect GBS would be done with the swabs collected, and subsequently, each patient signed an informed-consent form. All patient tests were performed at Calgary Laboratory Services (CLS), which provides services to a population of ∼1.5 million people in Calgary and surrounding areas in southern Alberta. All microbiology testing is done in a single regional core laboratory.

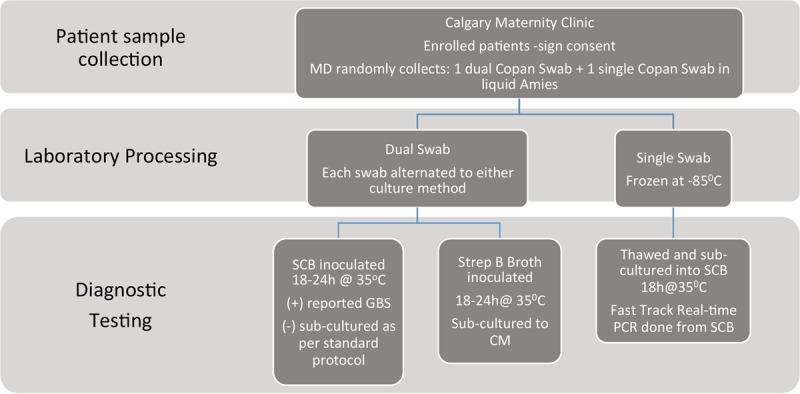

Figure 1 outlines the overall clinical and laboratory study workflow. Physicians used a dual-headed and a single Copan swab in liquid Amies transport medium to perform vaginal-rectal sample collection. All swabs were transported to the laboratory within 4 to 6 h after collection, where they were immediately processed. One swab from the dual collection was inoculated in accordance with our laboratory's routine culture method, and the other one was used to inoculate Strep Group B Broth, followed by StrepBSelect CM. The third swab was immediately frozen at −85°C for molecular testing. The routine culture methods used by CLS are compliant with CDC guidelines (8) and consist of the initial inoculation of an SCB (Hardy Diagnostics) culture, followed by subculture of negative SCB cultures by a method that assists with discrimination of normal flora (i.e., Enterococcus) (9). SCB cultures were incubated for 18 to 24 h at 35°C. All SCB cultures were read and reported as positive if a visible color change to orange or red from colorless occurred. All negative SCB cultures were subcultured onto 5% sheep blood agar with two neomycin disks (30 μg), incubated for another 18 to 24 h at 35°C, and analyzed for the presence of GBS colonies by standard phenotypic methods. StrepBSelect CM (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was stored and incubated with minimal exposure to light to ensure that the chromogens in the medium were not destroyed. CM cultures were performed in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. CM plates are opaque white, and GBS colonies appeared blue (turquoise, pale or sky blue) on this medium. Inoculated Strep Group B Broth was aerobically incubated for 18 to 24 h at 35°C before subculture to CM by using a single drop of the broth culture. Inoculated CM plates were aerobically at 35°C for 18 to 24 h before being read. If CM plates were negative after that time, they were reincubated for another 24 h before the final reading.

FIG 1.

Overall study specimen work flow.

The Fast-Track Diagnostics GBS qPCR assay (Sliema, Malta; Phoenix Airmid Biomedical Corp., Oakville, Ontario, Canada) was verified in a 94-well plate format on the m2000sp/m2000rt system (Abbott Molecular, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Swabs were inoculated into Strep Group B broths that were aerobically incubated 35°C for 18 to 24 h before nucleic acid extraction, which is required by the manufacturer. Both commercial manufacturers had preverified the method for performance of the GBS qPCR test kit on this instrument system. The qPCR assay targets the sip (surface immunogenic protein) gene and was otherwise performed in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Both CM and qPCR results were initially compared to the results of routine culture, including the total turnaround time of each test method. All samples were also tested by a second commercial qPCR method (i.e., Abbott IMDx Streptococcus Group B real-time PCR kit; Abbott Molecular) after initial broth enrichment as required by the manufacturer, but its overall performance was not reported because that assay is not commercially available. The Abbott IMDx GBS assay results were, however, used to resolve discrepancies between culture and Fast-Track qPCR results. The Abbott IMDx assay directly detects the GBS genome cfb gene (Christie-Atkins-Munch-Petersen factor) sequence. Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel (2010) spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp., Seattle, WA) and analyzed with Analyze-it Software (Microsoft Corp.). The established modified gold standard for defining a true positive sample was one where GBS grew in either routine or CM culture and was also positive by one of the qPCR methods or the sample was negative by either culture method but positive by both qPCR methods. This study was approved by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Calgary and Alberta Health Services (ethics ID, REB-13-1111-M001).

The annual costs of switching GBS testing in our laboratory to either CM or qPCR were compared to those of our current culture methods. Labor costs were based on the current hourly rates paid by CLS to medical laboratory assistants and medical laboratory technologists. Supply costs included the Canadian goods and services tax. All reported costs are in Canadian dollars.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by CLS.

H.B. supervised patient recruitment. T.L. performed all of the diagnostic testing. Commercial suppliers provided all of the required reagents, kits, and instrumentation.

None of the authors has any conflict of interest or disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schrag SJ, Stoll BJ. 2006. Early-onset neonatal sepsis in the era of widespread intrapartum chemoprophylaxis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 25:939–940. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000239267.42561.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Sanchez PJ, Faix RG, Poindexter BB, Van Meurs KP, Bizzarro MJ, Goldberg RN, Frantz ID III, Hale EC, Shankaran S, Kennedy K, Carlo WA, Watterberg KL, Bell EF, Walsh MC, Schibler K, Laptook AR, Shane AL, Schrag SJ, Das A, Higgins RD, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child H, Human Development Neonatal Research N. 2011. Early onset neonatal sepsis: the burden of group B streptococcal and E. coli disease continues. Pediatrics 127:817–826. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weston EJ, Pondo T, Lewis MM, Martell-Cleary P, Morin C, Jewell B, Daily P, Apostol M, Petit S, Farley M, Lynfield R, Reingold A, Hansen NI, Stoll BJ, Shane AL, Zell E, Schrag SJ. 2011. The burden of invasive early-onset neonatal sepsis in the United States, 2005–2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J 30:937–941. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318223bad2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis RL, Hasselquist MB, Cardenas V, Zerr DM, Kramer J, Zavitkovsky A, Schuchat A. 2001. Introduction of the new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention group B streptococcal prevention guideline at a large west coast health maintenance organization. Am J Obstet Gynecol 184:603–610. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.110308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuchat A. 2001. Group B streptococcal disease: from trials and tribulations to triumph and trepidation. Clin Infect Dis 33:751–756. doi: 10.1086/322697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schrag SJ, Zywicki S, Farley MM, Reingold AL, Harrison LH, Lefkowitz LB, Hadler JL, Danila R, Cieslak PR, Schuchat A. 2000. Group B streptococcal disease in the era of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. N Engl J Med 342:15–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001063420103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schrag SJ, Zell ER, Lynfield R, Roome A, Arnold KE, Craig AS, Harrison LH, Reingold A, Stefonek K, Smith G, Gamble M, Schuchat A, Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Team. 2002. A population-based comparison of strategies to prevent early-onset group B streptococcal disease in neonates. N Engl J Med 347:233–239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ, Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2010. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease—revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 59(RR-10):1–36. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5910a1.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Church DL, Baxter H, Lloyd T, Miller B, Elsayed S. 2008. Evaluation of StrepB Carrot Broth versus Lim broth for detection of group B streptococcus colonization status of near-term pregnant women. J Clin Microbiol 46:2780–2782. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00557-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Church DL, Baxter H, Lloyd T, Miller B, Gregson DB. 2011. Evaluation of the Xpert® group B streptococcus real-time polymerase chain reaction assay compared to StrepB Carrot Broth for the rapid intrapartum detection of group B streptococcus colonization. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 69:460–462. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz J, Robinson-Dunn B, Makin J, Boyanton BL Jr. 2012. Evaluation of the BD MAX GBS assay to detect Streptococcus group B in Lim broth-enriched antepartum vaginal-rectal specimens. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 73:97–98. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourgeois-Nicolaos N, Cordier AG, Guillet-Caruba C, Casanova F, Benachi A, Doucet-Populaire F. 2013. Evaluation of the Cepheid Xpert GBS assay for rapid detection of group B streptococci in amniotic fluids from pregnant women with premature rupture of membranes. J Clin Microbiol 51:1305–1306. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03356-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Helali N, Nguyen JC, Ly A, Giovangrandi Y, Trinquart L. 2009. Diagnostic accuracy of a rapid real-time polymerase chain reaction assay for universal intrapartum group B streptococcus screening. Clin Infect Dis 49:417–423. doi: 10.1086/600303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gavino M, Wang E. 2007. A comparison of a new rapid real-time polymerase chain reaction system to traditional culture in determining group B streptococcus colonization. Am J Obstet Gynecol 197:388.e1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munson E, Napierala M, Munson KL, Culver A, Hryciuk JE. 2010. Temporal characterization of carrot broth-enhanced real-time PCR as an alternative means for rapid detection of Streptococcus agalactiae from prenatal anorectal and vaginal screenings. J Clin Microbiol 48:4495–4500. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01734-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopper C, Oleksiuk M. 2013. Evaluation of a new screening medium for the detection of group B streptococci (GBS). Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Basingstoke, Hants, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craven RR, Weber CJ, Jennemann RA, Dunne WM Jr. 2010. Evaluation of a chromogenic agar for detection of group B streptococcus in pregnant women. J Clin Microbiol 48:3370–3371. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00221-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poisson DM, Evrard ML, Freneaux C, Vives MI, Mesnard L. 2011. Evaluation of CHROMagar StrepB agar, an aerobic chromogenic medium for prepartum vaginal-rectal group B Streptococcus screening. J Microbiol Methods 84:490–491. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Aila NA, Tency I, Claeys G, Saerens B, Cools P, Verstraelen H, Temmerman M, Verhelst R, Vaneechoutte M. 2010. Comparison of different sampling techniques and of different culture methods for detection of group B streptococcus carriage in pregnant women. BMC Infect Dis 10:285. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salem N, Anderson JJ. 2015. Evaluation of four chromogenic media for the isolation of group B streptococcus from vaginal specimens in pregnant women. Pathology 47:580–582. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El Aila NA, Tency I, Claeys G, Verstraelen H, Deschaght P, Decat E, Lopes dos Santos Santiago G, Cools P, Temmerman M, Vaneechoutte M. 2011. Comparison of culture with two different qPCR assays for detection of rectovaginal carriage of Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococci) in pregnant women. Res Microbiol 162:499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berg BR, Houseman JL, Garrasi MA, Young CL, Newton DW. 2013. Culture-based method with performance comparable to that of PCR-based methods for detection of group B streptococcus in screening samples from pregnant women. J Clin Microbiol 51:1253–1255. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02780-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Church D, Carson J, Gregson D. 2012. Point prevalence study of antibiotic susceptibility of genital group B streptococcus isolated from near-term pregnant women in Calgary, Alberta. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 23:121–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]