ABSTRACT

The objective of this study was to compare the diagnostic value of galactomannan (GM) detection in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and serum samples from nonneutropenic patients with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) and determine the optimal BALF GM cutoff value for pulmonary aspergillosis. GM detection in BALF and serum samples was performed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in 128 patients with clinically suspected nonneutropenic pulmonary aspergillosis between June 2014 and June 2016. On the basis of the clinical and pathological diagnoses, 8 patients were excluded because their diagnosis was uncertain. The remaining 120 patients were diagnosed with either IPA (n = 37), community-acquired pneumonia (CAP; n = 59), noninfectious diseases (n = 19), or tuberculosis (n = 5). At a cutoff optical density index (ODI) value of ≥0.5, the sensitivity of BALF GM detection was much higher than that of serum GM detection (75.68% versus 37.84%; P = 0.001), but there was no significant difference between their specificities (80.72% versus 87.14%; P = 0.286). At a cutoff value of ≥1.0, the sensitivity of BALF GM detection was still much higher than that of serum GM detection (64.86% versus 24.32%; P < 0.001), and their specificities were similar (90.36% versus 95.71%; P = 0.202). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis showed that when the BALF GM detection cutoff value was 0.7, its diagnostic value for pulmonary aspergillosis was optimized, and the sensitivity and specificity reached 72.97% and 89.16%, respectively. BALF GM detection was valuable for the diagnosis of IPA in nonneutropenic patients, and its diagnostic value was superior to that of serum GM detection. The optimal BALF GM cutoff value was 0.7.

KEYWORDS: invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, galactomannan antigen, nonneutropenic patients

INTRODUCTION

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) is mainly caused by Aspergillus fumigatus. Aspergillus species can invade the tracheal bronchus and lung directly, resulting in airway colonization, lung inflammatory granuloma, and even more serious sequelae, such as necrotizing pneumonia, and they can also affect other organs through hematogenous spread. Previously, IPA was recognized as occurring mainly in patients with neutrophil deficiencies. Such patients generally have serious immunosuppressive conditions, such as malignant hematopathy, solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplants, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, or are receiving long-term immunosuppressive therapy (1–3). However, it has increasingly been found that nonneutropenic patients, especially those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchiectasis, or previous tuberculosis, are also prone to pulmonary Aspergillus infections (2, 4–7). As lung biopsy is invasive and risky and microbiological tests, such as sputum fungal cultures, have very low sensitivities (8), the diagnostic criteria for IPA are based on its characteristic histopathology. Therefore, as IPA lacks characteristic clinical manifestations, its early diagnosis remains challenging.

Galactomannan (GM) is a polysaccharide antigen that exists primarily in the cell walls of Aspergillus species. GM may be released into the blood and other body fluids even in the early stages of Aspergillus invasion, and the presence of this antigen can be sustained for 1 to 8 weeks (9). Therefore, detection of the GM antigen level via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) can be useful in making an early diagnosis of IPA. Currently, serum GM detection is considered a microbiological diagnostic criterion for fungus infection in neutropenic patients, according to the guidelines of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) (2). The cutoff value for serum GM detection is generally set at 0.5. Recently, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) GM detection was also strongly recommended in the 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines as a test providing high-quality evidence in neutropenic patients, but its clinical application in nonneutropenic patients lacks evidence and its optimal threshold has not been determined (10, 11). Currently, there is no single standard for different specimens (11, 12).

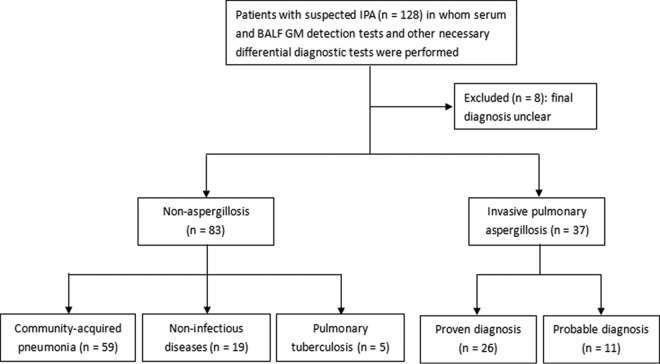

The objective of this study was to explore and compare the diagnostic value of GM detection between BALF and serum samples in patients with clinically suspected nonneutropenic IPA (Fig. 1) and to determine the optimal GM cutoff value for BALF GM detection.

FIG 1.

Study flowchart: screening and enrollment of patients. BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; GM, galactomannan.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics.

The characteristics of the 37 IPA patients and 83 nonaspergillosis patients who were studied are shown in Table 1. In the aspergillosis group, the proportions of patients with underlying pulmonary diseases, such as COPD, bronchiectasis, and previous tuberculosis, were similar to those in the nonaspergillosis group. Similarly, the proportions of patients with extrapulmonary diseases, such as diabetes mellitus and cerebrovascular accident, were similar in the 2 groups. However, a higher proportion of patients in the aspergillosis group than in the nonaspergillosis group was receiving corticosteroid therapy (21.62% versus 7.23%; P = 0.032).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the 37 patients with pulmonary aspergillosis and 83 without pulmonary aspergillosisd

| Characteristic | Results for: |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonaspergillosis group (n = 83) | Aspergillosis group (n = 37) | ||

| Sex (no. of males/no. of females) | 42/41 | 22/15 | 0.368a |

| Median (range) age (yr) | 52 (14–84) | 53 (14–85) | 0.949c |

| No. (%) of patients with the following underlying pulmonary diseases: | |||

| COPD | 7 (8.43) | 5 (13.51) | 0.511b |

| Bronchiectasis | 15 (18.07) | 10 (27.03) | 0.265a |

| Previous tuberculosis | 9 (10.84) | 9 (24.32) | 0.056a |

| No. (%) of patients with the following extrapulmonary diseases: | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (7.23) | 6 (16.22) | 0.185b |

| Hypertension | 12 (14.46) | 2 (5.41) | 0.222b |

| Chronic hepatitis | 5 (6.02) | 1 (2.70) | 0.665b |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1 (1.20) | 1 (2.70) | 1b |

| Corticosteroid treatment | 6 (7.23) | 8 (21.62) | 0.032b |

| No underlying diseases | 33 (39.76) | 3 (8.11) | <0.001a |

χ2 test.

Fisher's exact probability test.

Mann-Whitney U test.

Enumeration data were expressed as a percentage and analyzed by a χ2 test, Fisher's exact probability test, or the Mann-Whitney U test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Aspergillus cultures and GM antigen detection in patients with IPA.

Among the 37 patients in the IPA group, sputum and BALF Aspergillus culture data were available for 31 patients. Only 9 of the 31 sputum cultures (29.03%) were positive for Aspergillus, whereas 3 of the 31 BALF specimens (9.68%) were positive for Aspergillus (Table 2). The difference between the rates of positivity of the sputum and BALF Aspergillus cultures was not statistically significant (P = 0.054). This may have been due to the limited number of study patients.

TABLE 2.

Rates of positive Aspergillus cultures and GM detection in the 37 patients with IPAb

| Test and specimen | No. of patients with aspergillosis/total no. of patients (%) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus culture | ||

| Sputum | 9/31 (29.03) | 0.054 |

| BALF | 3/31 (9.68) | |

| GM detection | ||

| Serum | 14/37 (37.84) | 0.001 |

| BALF | 28/37 (75.68) |

χ2 test.

Enumeration data were expressed as a percentage and analyzed by a χ2 test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; GM, galactomannan.

In comparison with the Aspergillus culture data, GM was detected in BALF specimens from 28 of the 37 patients (75.68%), while it was detected in serum specimens from only 14 of the 37 patients (37.84%) (Table 2). This difference between serum GM and BALF GM detection was statistically significant (P = 0.001). Moreover, the rate of positive BALF GM detection was significantly higher than that of a positive Aspergillus culture for both sputum (P < 0.001) and BALF (P < 0.001). Although the rate of positive serum GM detection was also higher than that of a positive Aspergillus culture for BALF (P = 0.008), there was no significant difference between the rate of positive serum GM detection and that of a positive sputum Aspergillus culture (P = 0.446).

Comparison of BALF GM and serum GM levels in different groups.

When data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance, the BALF GM level in the IPA group was significantly higher than that in the community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) group (P < 0.001), the noninfectious disease group (P < 0.001), and the tuberculosis group (P = 0.005), but there were no significant differences between the last 3 groups (P > 0.05). However, serum GM levels showed no significant differences between the 4 groups (P = 0.069) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Differences between BALF GM and serum GM levels in the various groupsa

| Test | Difference between BALF GM and serum GM levels in: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillosis group (n = 37) | Nonaspergillosis group (n = 83) | CAP group (n = 59) | Noninfectious disease group (n = 19) | Tuberculosis group (n = 5) | |

| One-way analysis of variance | |||||

| BALF GM | 2.62 ± 2.34 | 0.56 ± 1.40 | 0.57 ± 0.60 | 0.36 ± 0.19 | |

| Serum GM | 0.74 ± 0.91 | 0.42 ± 0.65 | 0.28 ± 0.12 | 0.29 ± 0.21 | |

| Paired-samples t test | |||||

| BALF GM | 2.62 ± 2.34 | 0.57 ± 1.31 | |||

| Serum GM | 0.74 ± 0.91 | 0.38 ± 0.55 | |||

P values for differences between the groups are given in the text. BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; GM, galactomannan.

When data were analyzed by paired-samples t tests, the BALF GM level in the IPA group was significantly higher than the serum GM level (P < 0.001), but there were no significant differences between the BALF GM and serum GM levels in the nonaspergillosis groups (P = 0.202) (Table 3).

Comparison of IPA diagnostic efficiency between BALF and serum GM detection.

Both the sensitivity and negative predictive value (NPV) of the BALF GM detection test at a cutoff optical density index (ODI) value of ≥0.5 were significantly higher than those of the serum GM detection test (75.68% versus 37.84% [P = 0.001] for sensitivity and 88.16% versus 72.62% [P = 0.014] for NPV). Although the positive-predictive value (PPV) of the BALF GM detection test was higher than that of the serum GM detection test (63.64% versus 60.87%; P = 0.823) and the specificity was lower (80.72% versus 87.14%; P = 0.286), the differences between these values were not statistically significant.

At a cutoff value of ≥1.0, the sensitivity and NPV of the BALF GM detection test were still significantly higher than those of the serum GM detection test (64.86% versus 24.32% [P < 0.001] for sensitivity and 85.23% versus 70.53% [P = 0.017] for NPV), and the specificity of the BALF GM detection test was still slightly lower than that of the serum GM detection test (90.36% versus 95.71%; P = 0.202). The PPVs at this cutoff value were the same (75.00% versus 75.00%; P = 1) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Comparison of IPA diagnostic efficiency between BALF GM and serum GM detection testsa

| Sample and ODI | False-positive rate (%) | False-negative rate (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Positive-likelihood ratio | Negative-likelihood ratio | Youden index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALF GM | |||||||||

| ≥0.5 | 19.28 | 24.32 | 75.68 | 80.72 | 63.64 | 88.16 | 3.9253 | 0.3013 | 0.564 |

| ≥1.0 | 9.64 | 35.14 | 64.86 | 90.36 | 75.00 | 85.23 | 6.7282 | 0.3889 | 0.5522 |

| Serum GM | |||||||||

| ≥0.5 | 12.86 | 62.16 | 37.84 | 87.14 | 60.87 | 72.62 | 2.9425 | 0.7133 | 0.2498 |

| ≥1.0 | 4.29 | 75.68 | 24.32 | 95.71 | 75.00 | 70.53 | 5.669 | 0.7907 | 0.2003 |

Sensitivities, specificities, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive values (NPV) were used to compare the diagnostic value of BALF GM and serum GM detection. BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; GM, galactomannan; ODI, optical density index.

The sensitivity and NPV of the BALF GM detection test at a cutoff value of ≥1.0 were also significantly higher than those of the serum GM detection test at a cutoff value of ≥0.5 (64.86% versus 37.84% [P = 0.02] for sensitivity and 85.23% versus 72.62% [P = 0.042] for NPV), as was the PPV of the BALF GM detection test at a cutoff value of ≥1.0 in comparison with that of the serum GM detection test at a cutoff value of ≥0.5 (75.00% versus 60.87%; P = 0.264). However, their specificities at these cutoff values were similar (90.36% versus 87.14%; P = 0.527). We also calculated the positive-likelihood ratios and negative-likelihood ratios at different cutoff values in order to avoid the influence of the prevalence of the disease. Whether the values were determined at a cutoff value of ≥0.5 or ≥1.0, the positive-likelihood ratios of the BALF GM test were all higher than those of the serum GM test (3.925 versus 2.943 for a cutoff value of ≥0.5 and 6.728 versus 5.670 for a cutoff value of ≥1.0), and the negative-likelihood ratios of the BALF GM test were all lower than those of the serum GM test (0.301 versus 0.713 for a cutoff value of ≥0.5 and 0.390 versus 0.791 for a cutoff value of ≥1.0) (Table 4).

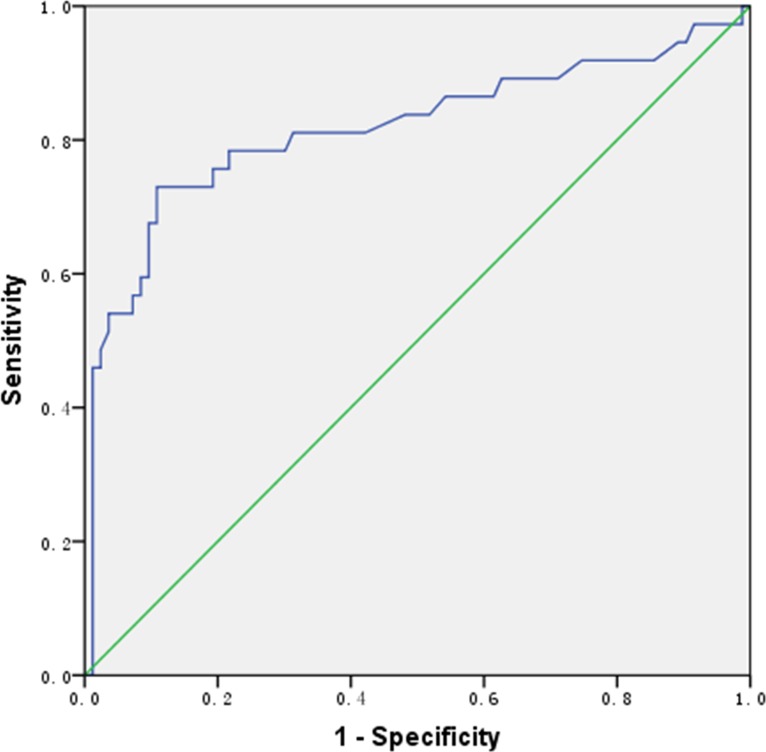

Optimal cutoff value for BALF GM detection.

As shown in the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve in Fig. 2, the diagnostic value of BALF GM detection for IPA was optimal when the cutoff value was 0.70, at which value the sensitivity and specificity of the test were 72.97% and 89.16%, respectively. The PPV and NPV were 75.00% and 88.10%, respectively. The area under the ROC curve was 0.817 (standard error, 0.049; 95% confidence interval, 0.720 to 0.914), and the Youden index (refer to the Materials and Methods section) was 0.6213. The sensitivity of the BALF GM test reached 97.30% when its cutoff value was 0.14, but the specificity was extremely low (only 8.43%); when the cutoff value was 1.485, the specificity of the BALF GM test reached 95.18% and the sensitivity was 54.05%.

FIG 2.

ROC curve for bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) galactomannan (GM) detection.

DISCUSSION

As IPA has no characteristic clinical manifestations, its early diagnosis is challenging, especially for nonneutropenic patients due to their lack of obvious risk factors. Delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis of IPA in these patients could result in serious problems, such as drug toxicity due to inappropriate treatment, high medical expenses, and mortality (13). Thus, early diagnosis is critical for their management. Currently, the efficiency of BALF and serum GM detection for the early diagnosis of IPA has been clearly demonstrated only in neutropenic patients (9), and evidence for BALF and serum GM detection in nonneutropenic patients is lacking. Furthermore, there are no defined cutoff values for BALF GM detection in patients with IPA.

The results of the present study indicate that in nonneutropenic patients, pulmonary aspergillosis tends to occur in those who have underlying pulmonary diseases, such as COPD, bronchiectasis, and previous tuberculosis, or who are receiving long-term corticosteroid therapy. We found that the differences between aspergillosis and nonaspergillosis patients were not statistically significant, except for the use of corticosteroids, which suggests that corticosteroid treatment may be a risk factor for IPA. We also found that positive Aspergillus culture rates in both sputum samples and BALF specimens (29.03% and 9.68%, respectively) and the serum GM detection rate (37.84%) were all significantly lower than the BALF GM detection rate (75.68%) (P < 0.05). Thus, BALF GM detection is much more sensitive than Aspergillus cultures and serum GM detection.

The differences in BALF GM detection between the IPA group and the other 3 patient groups (the CAP, noninfectious disease, and tuberculosis groups) were all statistically significant. However, for serum GM detection, there were no statistically significant differences between the 4 groups. These results indicate that BALF GM detection is a better way to distinguish aspergillosis from other infectious lung diseases. There are several possible reasons for this. First, BALF specimens are taken at the site of infection, where GM antigens are likely to be much more abundant than they are in serum, especially in nonneutropenic aspergillosis patients who have less blood vessel invasion by Aspergillus hyphae. Second, neutrophils in the serum may eliminate GM antigens via the mannan-binding receptor, which decreases the serum GM level (14, 15). These findings suggest that BALF GM is more valuable than serum GM for the early diagnosis of IPA in nonneutropenic patients.

When the cutoff value was set at ≥0.5 in this study, the sensitivity of the BALF GM detection test was significantly higher than that of the serum GM detection test. Furthermore, the PPV and NPV of the BALF GM detection test were also higher than those of the serum GM detection test, but the specificity of the BALF GM detection test was slightly lower than that of the serum GM detection test. At a higher cutoff value of ≥1.0, the sensitivity and NPV of the BALF GM detection test declined but were still significantly higher than those of the serum GM detection test, while the specificity and PPV of the BALF GM detection test increased to levels similar to those of the serum GM detection test. Currently, few studies of patients with nonneutropenic pulmonary aspergillosis have been reported. At a cutoff value of ≥0.5 or ≥1.0, BALF GM detection test sensitivities of 57.1% to 100% for the diagnosis of nonneutropenic IPA and specificities ranging from 47.1% to 92.1% have been reported (16–18). The BALF GM detection test sensitivities and specificities recorded in our study were within the ranges reported in these studies. Comparison of the positive-likelihood ratios and negative-likelihood ratios of the BALF GM and serum GM tests at different cutoff values indicated that the BALF GM test was more helpful for the diagnosis of IPA than the serum GM test. Irrespective of whether the cutoff value was ≥0.5 or ≥1.0, the serum GM detection test exhibited a low sensitivity, which may lead to a high rate of delayed diagnosis.

We hypothesized that neither ≥0.5 nor ≥1.0 is the optimal cutoff value for the BALF GM detection test, because the specificity and PPV were not sufficiently high. When the BALF GM cutoff value was set at ≥1.0, the sensitivity of the test declined, which could lead to a delay in diagnosis. By ROC curve analysis, we found that the optimal cutoff value for BALF GM detection was 0.70, at which level the sensitivity and specificity of the test were 72.97% and 89.16%, respectively. Other studies in which ROC curve analysis was applied have reported optimal BALF GM cutoff values ranging from 0.5 to 1.18 in nonneutropenic patients with pulmonary aspergillosis (16–19). Among these studies, one reported the same optimal cutoff value of 0.7 as our study (19), while another found that the optimal cutoff value was 0.8 (16), which was higher than that of our study. The higher value in the latter study may have been due to the fact that all the patients were critically ill with COPD. As the pulmonary structures and defense functions of these patients were severely damaged, Aspergillus may have been able to colonize the airway and lung parenchyma more readily and result in IPA. A study that had a mixed population that mainly included patients with chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis (CNPA) and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) rather than IPA found that the minimum optimal cutoff value was 0.5 (17), while the maximum optimal cutoff value reported in another study was 1.18 (18). However, the latter study had a very low prevalence rate (8.22%), as only 6 of 73 nonimmunocompromised patients had pulmonary aspergillosis. The corresponding sensitivities and specificities of the BALF GM detection test at the optimal cutoff values of 0.8 and 0.7 reported in 2 of the studies mentioned above (16, 19), based on ROC curves, were 88.9% to 100% and 87.9% to 100%, respectively. The optimal cutoff value found in our study (0.7) was similar to the values found in these 2 studies, but the sensitivity was lower (72.97%). Whereas the patient populations in the 2 studies referred to above were nonneutropenic intensive care unit (ICU) patients or critically ill patients with COPD, we studied a mixed patient population.

A meta-analysis of studies mainly containing immunocompromised patients reported a pooled sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 94% (20). Another larger meta-analysis of studies containing mixed populations of both immunocompromised and nonimmunocompromised patients reported a pooled sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 89%, and the optimal cutoff value was found to be 1.0 (21). Consequently, differences in the study populations may have been responsible for the different sensitivity results. As there may be a host of different factors or susceptible subgroups in populations with nonneutropenic IPA, a larger sample size and stratification of patients according to their underlying diseases are necessary. Nevertheless, our results suggest that when a cutoff value of 0.70 is used, BALF GM detection has a higher efficiency than serum GM detection for the diagnosis of IPA in nonneutropenic patients.

In summary, BALF GM detection is valuable for the early diagnosis of IPA in nonneutropenic patients and is superior to serum GM detection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study patients.

Between June 2014 and June 2016, 128 nonneutropenic patients (peripheral blood neutrophil counts > 0.5 × 109/liter) who were suspected to have IPA underwent serum and BALF GM detection tests at the Nanjing, China, Jinling Hospital. After excluding 8 cases with an unknown diagnosis, 120 patients were diagnosed as having either IPA (n = 37), community-acquired pneumonia (CAP; n = 59), noninfectious diseases (n = 19), or tuberculosis (n = 5) (Fig. 1).

The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Nanjing Jinling Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients who participated in the study.

Diagnostic criteria for IPA.

The diagnostic criteria applied for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA), according to the definitions provided in the EORTC/MSG guidelines, were (i) the presence of host factors for IPA, including solid organ transplant, connective tissue disorders, or usage of immunosuppressive agents, such as corticosteroids; (ii) the presence of radiological features consistent with pulmonary aspergillosis on a computed tomography (CT) scan, such as dense, well-circumscribed lesions with or without a halo sign, an air crescent sign, or cavity; (iii) mycologic evidence of Aspergillus, such as a positive Aspergillus culture from qualified specimens (including sputum and BALF) or a positive serum GM detection result (at a cutoff value of ≥0.5); and (iv) histological evidence of Aspergillus hyphae in lung biopsy specimens or a positive Aspergillus culture from lung biopsy specimens. A proven diagnosis was made when patients met the fourth criterion, a probable diagnosis was made when patients met the first 3 criteria, and a possible diagnosis was made when patients met the first 2 criteria. Among the 37 patients in the IPA group, 26 had a proven diagnosis and 11 had a probable diagnosis. No patients with possible diagnoses were included in this study.

Diagnostic criteria for CAP.

The diagnostic criteria applied for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) were (i) a new onset of cough, expectoration, or an exacerbation of preexisting respiratory tract symptoms with a purulent sputum, with or without chest pain; (ii) the presence of fever; (iii) signs of lung consolidation and/or moist rales; (iv) a white blood cell (WBC) count of >10 × 109/liter or <4 × 109/liter, with or without a nuclear left shift of the cells; and (v) patchy infiltration or interstitial changes evident on a chest X-ray, with or without pleural effusion. Patients with a community-onset illness who met any one of the first 4 criteria or who met the 5th criterion were clinically diagnosed as having CAP. A final diagnosis of CAP was made after a differential diagnosis to exclude other diseases and a positive response was obtained with empirical antimicrobial treatment.

Diagnostic criteria for tuberculosis.

In all the patients with tuberculosis, tuberculosis was diagnosed via histological evidence of tuberculosis in lung biopsy samples or by a positive result in sputum acid-fast staining.

Noninfectious diseases group.

The noninfectious diseases diagnosed in the noninfectious diseases group included interstitial lung disease (n = 3), organizing pneumonia (n = 8), antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (n = 2), airway hyperreactivity (n = 1), autoimmune disorders (n = 1), and newly diagnosed lung cancer or metastatic lung tumors (n = 4).

Collection of BALF and serum samples.

The preoperative preparation and intraoperative monitoring of patients met the standards for bronchoscopy. Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed on the basis of a recent CT scan result and the location of the target segmental or subsegmental bronchus. Saline solution (instilled volume, about 50 ml) was administered at room temperature, and administration of the saline solution was repeated 2 to 3 times. BALF was collected in a sterile tube and sent for laboratory analysis within half an hour. Both the BALF and serum samples were collected within 24 h after the patients had been admitted to the hospital.

GM detection.

Both BALF and serum specimens were routinely sent to a microbiological laboratory for GM detection, which was performed using a double-sandwich ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions for the Platelia Aspergillus kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA). The optical density (OD) value for each hole on the microplate reader was read, and the GM detection value in the serum or BALF samples was derived by the following formula: specimen OD value divided by standard OD value. A serum GM value of 0.5 or greater was considered positive (2). As there is currently no widely accepted cutoff value for BALF GM, we used values of 0.5 and 1.0 to calculate the relative parameters.

Statistical methods.

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 20.0) software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). One-way analysis of variance and t tests were used to analyze differences in GM detection between BALF and serum samples in the 4 patient groups. Enumeration data were expressed as percentages and analyzed by using χ2 tests. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In determining the sensitivity and specificity of BALF and serum GM detection for the diagnosis of IPA, we calculated the Youden index [i.e., sensitivity + (specificity − 1)]. This value indicates the ability of screening methods to identify real patients. The greater that the Youden index is, the greater that the authenticity of the screening procedure is.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Technology Support Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology (no. 2015BAI12B11) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81330035).

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Editorial assistance with the manuscript was provided by Content Ed Net, Shanghai Co. Ltd.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lopez-Medrano F, Silva JT, Fernandez-Ruiz M, Carver PL, van Delden C, Merino E, Pérez-Saez MJ, Montero M, Coussement J, de Abreu Mazzolin M, Cervera C, Santos L, Sabé N, Scemla A, Cordero E, Cruzado-Vega L, Martín-Moreno PL, Len Ó, Rudas E, de León AP, Arriola M, Lauzurica R, David M, González-Rico C, Henríquez-Palop F, Fortún J, Nucci M, Manuel O, Paño-Pardo JR, Montejo M, Muñoz P, Sánchez-Sobrino B, Mazuecos A, Pascual J, Horcajada JP, Lecompte T, Lumbreras C, Moreno A, Carratalà J, Blanes M, Hernández D, Hernández-Méndez EA, Fariñas MC, Perelló-Carrascosa M, Morales JM, Andrés A, Aguado JM. 2016. Risk factors associated with early invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in kidney transplant recipients: results from a multinational matched case-control study. Am J Transplant 16:2148–2157. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, Pappas PG, Maertens J, Lortholary O, Kauffman CA, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Maschmeyer G, Bille J, Dismukes WE, Herbrecht R, Hope WW, Kibbler CC, Kullberg BJ, Marr KA, Muñoz P, Odds FC, Perfect JR, Restrepo A, Ruhnke M, Segal BH, Sobel JD, Sorrell TC, Viscoli C, Wingard JR, Zaoutis T, Bennett JE. 2008. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 46:1813–1821. doi: 10.1086/588660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pagano L, Caira M, Candoni A, Offidani M, Fianchi L, Martino B, Pastore D, Picardi M, Bonini A, Chierichini A, Fanci R, Caramatti C, Invernizzi R, Mattei D, Mitra ME, Melillo L, Aversa F, Van Lint MT, Falcucci P, Valentini CG, Girmenia C, Nosari A. 2006. The epidemiology of fungal infections in patients with hematologic malignancies: the SEIFEM-2004 study. Haematologica 91:1068–1075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barberan J, Mensa J. 2014. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Rev Iberoam Micol 31:237–241. (In Spanish.) doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delsuc C, Cottereau A, Frealle E, Bienvenu AL, Dessein R, Jarraud S, Dumitrescu O, Le Maréchal M, Wallet F, Friggeri A, Argaud L, Rimmelé T, Nseir S, Ader F. 2015. Putative invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a matched cohort study. Crit Care 19:421. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1140-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taccone FS, Van den Abeele AM, Bulpa P, Misset B, Meersseman W, Cardoso T, Paiva JA, Blasco-Navalpotro M, De Laere E, Dimopoulos G, Rello J, Vogelaers D, Blot SI, AspICU Study Investigators. 2015. Epidemiology of invasive aspergillosis in critically ill patients: clinical presentation, underlying conditions, and outcomes. Crit Care 19:7. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0722-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreno-González G, Ricart de Mesones A, Tazi-Mezalek R, Marron-Moya MT, Rosell A, Mañez R. 2016. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis with disseminated infection in immunocompetent patient. Can Respir J 2016:7984032. doi: 10.1155/2016/7984032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarrand JJ, Lichterfeld M, Warraich I, Luna M, Han XY, May GS, Kontoyiannis DP. 2003. Diagnosis of invasive septate mold infections. A correlation of microbiological culture and histologic or cytologic examination. Am J Clin Pathol 119:854–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bretagne S, Marmorat-Khuong A, Kuentz M, Latge JP, Bart-Delabesse E, Cordonnier C. 1997. Serum Aspergillus galactomannan antigen testing by sandwich ELISA: practical use in neutropenic patients. J Infect 35:7–15. doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(97)90833-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, Fishman JA, Hadley S, Herbrecht R, Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Nguyen MH, Segal BH, Steinbach WJ, Stevens DA, Walsh TJ, Wingard JR, Young JA, Bennett JE. 2016. Executive summary: practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 63:433–442. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Haese J, Theunissen K, Vermeulen E, Schoemans H, De Vlieger G, Lammertijn L, Meersseman P, Meersseman W, Lagrou K, Maertens J. 2012. Detection of galactomannan in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples of patients at risk for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: analytical and clinical validity. J Clin Microbiol 50:1258–1263. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06423-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B, Pagano L, Pagliari G, Fianchi L, Mele L, La Sorda M, Franco A, Fadda G. 2003. Comparison of real-time PCR, conventional PCR, and galactomannan antigen detection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples from hematology patients for diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol 41:3922–3925. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3922-3925.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornillet A, Camus C, Nimubona S, Gandemer V, Tattevin P, Belleguic C, Chevrier S, Meunier C, Lebert C, Aupée M, Caulet-Maugendre S, Faucheux M, Lelong B, Leray E, Guiguen C, Gangneux JP. 2006. Comparison of epidemiological, clinical, and biological features of invasive aspergillosis in neutropenic and nonneutropenic patients: a 6-year survey. Clin Infect Dis 43:577–584. doi: 10.1086/505870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cordonnier C, Escudier E, Verra F, Brochard L, Bernaudin JF, Fleury-Feith J. 1994. Bronchoalveolar lavage during neutropenic episodes: diagnostic yield and cellular pattern. Eur Respir J 7:114–120. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07010114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett JE, Friedman MM, Dupont B. 1987. Receptor-mediated clearance of Aspergillus galactomannan. J Infect Dis 155:1005–1010. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.5.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He H, Ding L, Sun B, Li F, Zhan Q. 2012. Role of galactomannan determinations in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples from critically ill patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for the diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: a prospective study. Crit Care 16:R138. doi: 10.1186/cc11443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kono Y, Tsushima K, Yamaguchi K, Kurita N, Soeda S, Fujiwara A, Sugiyama S, Togashi Y, Kasagi S, To M, To Y, Setoguchi Y. 2013. The utility of galactomannan antigen in the bronchial washing and serum for diagnosing pulmonary aspergillosis. Respir Med 107:1094–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen MH, Jaber R, Leather HL, Wingard JR, Staley B, Wheat LJ, Wheat LJ, Cline CL, Baz M, Rand KH, Clancy CJ. 2007. Use of bronchoalveolar lavage to detect galactomannan for diagnosis of pulmonary aspergillosis among nonimmunocompromised hosts. J Clin Microbiol 45:2787–2792. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00716-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozger S, Hızel K, Kalkancı A, Aydogdu M, Civil F, Dizbay M, Gürsel G. 2015. Evaluation of risk factors for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and detection of diagnostic values of galactomannan and PCR methods in bronchoalveolar lavage samples from non-neutropenic intensive care unit patients. Mikrobiyol Bul 49:565–575. (In Turkish.) doi: 10.5578/mb.9906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo YL, Chen YQ, Wang K, Qin SM, Wu C, Kong JL. 2010. Accuracy of BAL galactomannan in diagnosing invasive aspergillosis: a bivariate metaanalysis and systematic review. Chest 138:817. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zou M, Tang L, Zhao S, Zhao Z, Chen L, Chen P, Huang Z, Li J, Chen L, Fan X. 2012. Systematic review and meta-analysis of detecting galactomannan in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for diagnosing invasive aspergillosis. PLoS One 7:e43347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]