ABSTRACT

Noroviruses are the most frequent cause of epidemic acute gastroenteritis in the United States. Between September 2013 and August 2016, 2,715 genotyped norovirus outbreaks were submitted to CaliciNet. GII.4 Sydney viruses caused 58% of the outbreaks during these years. A GII.4 Sydney virus with a novel GII.P16 polymerase emerged in November 2015, causing 60% of all GII.4 outbreaks in the 2015-2016 season. Several genotypes detected were associated with more than one polymerase type, including GI.3, GII.2, GII.3, GII.4 Sydney, GII.13, and GII.17, four of which harbored GII.P16 polymerases. GII.P16 polymerase sequences associated with GII.2 and GII.4 Sydney viruses were nearly identical, suggesting common ancestry. Other common genotypes, each causing 5 to 17% of outbreaks in a season, included GI.3, GI.5, GII.2, GII.3, GII.6, GII.13, and GII.17 Kawasaki 308. Acquisition of alternative RNA polymerases by recombination is an important mechanism for norovirus evolution and a phenomenon that was shown to occur more frequently than previously recognized in the United States. Continued molecular surveillance of noroviruses, including typing of both polymerase and capsid genes, is important for monitoring emerging strains in our continued efforts to reduce the overall burden of norovirus disease.

KEYWORDS: genetic recombination, genotypic identification, noroviruses

INTRODUCTION

Noroviruses are the leading cause of acute gastroenteritis in all age groups, causing 18% of all cases globally (1). In the United States, noroviruses are also the most common cause of outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis (2). Symptoms of vomiting and/or diarrhea are normally self-limiting, but severe outcomes and deaths have been reported, particularly among young children and elderly adults (3). In several countries where rotavirus vaccine programs have been successfully implemented, norovirus is now recognized as the leading cause of pediatric gastroenteritis (4, 5). Over half of all norovirus outbreaks in the United States and other industrialized countries occur in health care settings, including hospitals and long-term-care facilities (6). Other common outbreak settings include restaurants and catered events, cruise ships, schools, child care facilities, and other institutional settings, the global economic impact of which is estimated to be over $64 billion a year (7, 8).

The norovirus single-stranded RNA genome, approximately 7.5 kb in length, is divided into three open reading frames (ORFs). ORF1 encodes the nonstructural viral proteins including the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. ORF2 and ORF3 encode the respective major (VP1) and minor (VP2) structural proteins. VP1 can be further divided into a highly conserved N-terminal shell (S) domain and a protruding (P) domain consisting of the central P1 region and an inserted, highly variable P2 region, which is the most surface-exposed region of the norovirus capsid and therefore the target for both neutralizing antibodies and receptor binding.

Based on phylogenetic clustering of the complete VP1 amino acid sequence, norovirus can be classified into at least seven recognized norovirus genogroups (GI to GVII), among which viruses from the GI, GII, and GIV groups infect humans (9, 10). Genogroups can be further divided into 9 GI, 22 GII, and 2 GIV genotypes (10). Because complete sequencing of VP1 is not routinely performed by most laboratories, smaller regions of ORF2 (e.g., regions C and D) are often used to genotype norovirus strains (8, 9). In addition, norovirus strains can be genotyped using partial regions of the ORF1 RNA polymerase (P)-encoding region (regions A and B), which has been performed for over a decade (11–13). At least 14 GI polymerase (GI.P) types and 27 GII.P types have been described in the polymerase region (10). A dual-nomenclature system has been proposed for GI and GII noroviruses (9); however, until recently few laboratories performed typing using both ORF1 and ORF2 sequences. Recombination among norovirus strains occurs primarily at the ORF1-ORF2 junction and happens more often than previously recognized (14–18).

Since the mid-1990s, genogroup II genotype 4 (GII.4) noroviruses have caused the majority of outbreaks and sporadic cases worldwide (19). Since 2002, new GII.4 variants have emerged every 2 to 3 years, resulting in epidemics and sometimes global pandemics (20). GII.4 norovirus evolution is driven by antigenic drift and recombination (21). Mutations of key epitopes in the P2 domain of ORF2 allow emergent variants to escape recognition by neutralizing antibodies generated by previously circulating GII.4 variants (22). Such mutations can also alter the repertoire of histo-blood group antigen ([HBGA] attachment factors associated with genetic susceptibility to certain norovirus strains [23]) that GII.4 variants recognize, potentially allowing previously naive populations to become genetically susceptible (24). Intragenotypic (possibly also intergenotypic) recombination occurring primarily at the ORF1-ORF2 junction, but also within ORF2 and at the ORF2-ORF3 junction, is another mechanism for the emergence of pandemic GII.4 variants (25). Epidemic GII.4 variants reported in 1995 to 1996, 2002, 2004, and 2006 evolved primarily through antigenic drift, and GII.4 variants reported in 2009 and 2012 evolved through recombination (21). Some of these variants were responsible for increased outbreak activity among vulnerable populations and in health care settings (19, 25); however, this was not the case for GII.4 Sydney, which emerged in 2012 (26). Non-GII.4 strains can also contribute significantly to the norovirus disease burden. GII.12, GII.1, and GI.6 viruses have been reported to cocirculate with GII.4 strains and to contribute to as much as 15% of all norovirus outbreaks during a season (8).

In this report, we describe the molecular epidemiology of norovirus outbreaks in the United States from 1 September 2013 to 31 August 2016 as a continuation of our previous publications (8, 27). In the winter of 2015 to 2016, a novel GII.4 virus emerged which had similarities to the pandemic GII.4 Sydney virus in the capsid region but had a unique polymerase sequence (GII.P16). By combining two previously published typing protocols (12, 28), we implemented a dual-typing (polymerase and capsid [P-C]) assay, allowing robust detection of multiple cocirculating GI and GII norovirus genotypes.

RESULTS

Genotype and seasonal distribution of norovirus outbreaks submitted to CaliciNet, 2013 to 2016.

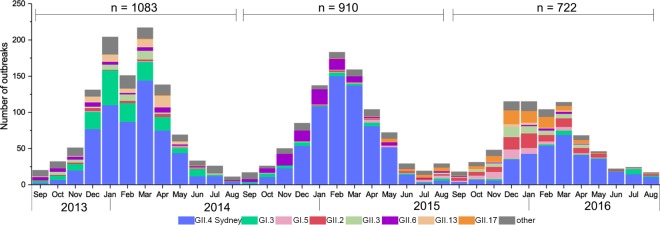

A total of 2,715 genotyped norovirus outbreaks were submitted to CaliciNet from 1 September 2013 through 31 August 2016; 1,083 outbreaks were submitted in 2013 to 2014, 910 outbreaks were submitted in 2014 to 2015, and 722 outbreaks were submitted in 2015 to 2016 (Fig. 1). GII.4 Sydney viruses caused 595 (54.9%), 641 (70.4%), and 338 (46.8%) outbreaks, respectively, during the 3-year study (Table 1). Other genotypes that caused 5% or more outbreaks for one or more years included GI.3, GI.5, GII.2, GII.3, GII.6, GII.13, and GII.17 (Fig. 1; Table 1). Genotypes representing less than 5% of all outbreaks included the following genotypes: GI.1, GI.2, GI.4, GI.6, GI.7, GI.9, GII.1, GII.7, GII.8, GII.10, GII.12, GII.14, GII.15, GII.25 (a tentative new genotype), and GIV and mixed outbreaks containing more than one genotype (Table 1).

FIG 1.

Distribution, by month, of norovirus genotypes from outbreaks submitted to CaliciNet from 1 September 2013 through 31 August 2016. “Other” includes the following capsid genotypes: GI.1, GI.2, GI.4, GI.6, GI.7, GI.9, GII.1, GII.5, GII.7, GII.8, GII.4 New Orleans, GII.4 Den Haag, GII.10, GII.12, GII.14, GII.15, a tentative novel genotype, GIV, and mixed outbreaks containing more than one GI or GII genotype.

TABLE 1.

Number and percentage of outbreaks by genotype and by year

| Genotype (year) | No. (%) of outbreaks |

Total no. (%) of outbreaks | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013–2014 | 2014–2015 | 2015–2016 | ||

| GI.1 | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 7 (0.3) |

| GI.2 | 13 (1.2) | 43 (4.7) | 8 (1.1) | 64 (2.4) |

| GI.3 | 181 (16.7) | 36 (4.0) | 24 (3.3) | 241 (8.9) |

| GI.4 | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 6 (0.2) |

| GI.5 | 4 (0.4) | 17 (1.9) | 51 (7.1) | 72 (2.7) |

| GI.6 | 20 (1.9) | 5 (0.6) | 3 (0.4) | 28 (1.0) |

| GI.7 | 4 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.2) |

| GI.9 | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) |

| GII.1 | 5 (0.5) | 5 (0.6) | 29 (4.0) | 39 (1.4) |

| GII.2 | 21 (1.9) | 12 (1.3) | 90 (12.5) | 123 (4.5) |

| GII.3 | 42 (3.9) | 6 (0.7) | 50 (6.9) | 98 (3.6) |

| GII.4 Den Haag (2006) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) |

| GII.4 New Orleans (2009) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) |

| GII.4 Sydney (2012) | 595 (54.9) | 641 (70.4) | 338 (46.8) | 1,574 (58.0) |

| GII.5 | 15 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (0.6) |

| GII.6 | 42 (3.9) | 94 (10.3) | 11 (1.5) | 147 (5.4) |

| GII.7 | 44 (4.1) | 10 (1.1) | 4 (0.6) | 58 (2.1) |

| GII.8 | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) |

| GII.10 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.4) | 4 (0.2) |

| GII.12 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| GII.13 | 58 (5.4) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (1.8) | 71 (2.6) |

| GII.14 | 10 (0.9) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.4) | 14 (0.5) |

| GII.15 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| GII.17 | 3 (0.3) | 19 (2.1) | 75 (10.4) | 97 (3.6) |

| GII.25 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| GIV | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) |

| Mixed | 12 (1.1) | 10 (1.1) | 14 (1.9) | 36 (1.3) |

| Total | 1,083 (100.0) | 910 (100.0) | 722 (100.0) | 2,715 (100.0) |

There was a clear winter seasonality for norovirus outbreaks that was driven primarily by GII.4 noroviruses (Fig. 1). The proportion of outbreaks caused by all norovirus genotypes occurring from 1 January through 31 March (3-year total of 1,385 outbreaks [51.0%], with 52.8%, 52.8%, and 46.1% of all outbreaks each consecutive year) was higher than the proportion of outbreaks occurring in other quarters of the year (P < 0.01). Among GII.4 noroviruses, 57.2%, 61.5%, and 49.1% of all GII.4 outbreaks occurred during these months for the consecutive years, more than any other quarter (P < 0.01). However, outbreaks caused by other genotypes also peaked during the winter months: GI.3 and GII.13 in the winter of 2013 to 2014, GII.6 in the winter of 2014 to 2015, and GI.5, GII.2, GII.3, and GII.17 Kawasaki 308 in the winter of 2015 to 2016 (Fig. 1). GII.17 Kawasaki 308 noroviruses caused 10.4% of all outbreaks in 2015 to 2016 (Table 1).

Emergence of a novel GII.4 Sydney recombinant.

In November 2015, GII.4 viruses were detected that had >2% (3.7% to 4.9%) nucleotide difference in region C compared to the GII.4 Sydney viruses that had been circulating since 2012. Complete genome sequencing by next-generation sequencing (NGS) showed that this was a recombinant virus with a GII.4 Sydney capsid and a GII.P16 polymerase (GII.P16-GII.4 Sydney), closely related to a virus detected in Japan in 2016 (29). In 2015 to 2016, 208 (61.5%) of the 338 GII.4 outbreaks and 28% of the total number of outbreaks were caused by this novel GII.P16 recombinant. In addition, GII.4 Sydney viruses sharing >98% nucleotide identity with the GII.4 Sydney reference strain of the capsid gene caused 130 (38.5%) of all GII.4 outbreaks and 18% of all outbreaks in 2015 to 2016.

Additional recombinant noroviruses with GII.P16 polymerases were found among GII.2, GII.3, and GII.13 genotypes.

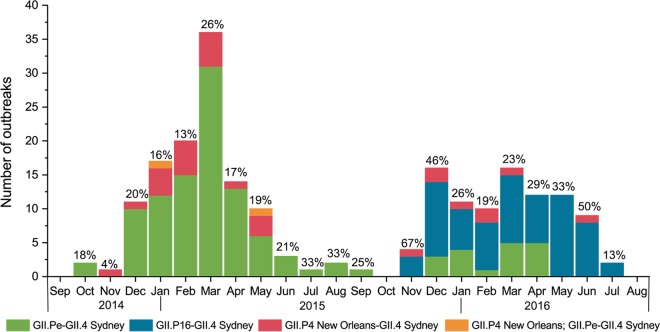

Dual typing was performed for viruses from 410 outbreaks (Table 2). Several genotypes were detected that were associated with more than one polymerase type, including GI.3, GII.2, GII.3, GII.4 Sydney, GII.13, and GII.17. The GII.P16 polymerase was found associated with GII.2, GII.3, GII.4 Sydney, and GII.13 genotypes. In addition, noroviruses having the GII.Pe polymerase were primarily associated with GII.4 Sydney but also with three GII.17 outbreaks occurring in 2015. These GII.Pe-GII.17 viruses shared >98% nucleotide identity with a GII.Pe-GII.17 virus from Hong Kong in 2015. All other GII.17 viruses had the GII.P17 polymerase typical of GII.17 Kawasaki 308 viruses. Viruses with GII.P12 and GII.P21 polymerases were associated with GII.3. Of note, in samples from 30 outbreaks, GII.4 Sydney viruses with a GII.P4 New Orleans polymerase were detected (Table 2). This virus was detected in 2014 to 2016 although GII.Pe-GII.4 Sydney predominated in 2014 to 2015, and GII.P16-GII.4 Sydney predominated the following year (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Dual typing of norovirus outbreaks reported in CaliciNet, 1 September 2013 through 31 August 2016

| Genogroup and capsid genotype | Percentage of outbreaks available for dual typing | Polymerase type | No. of outbreaks with dual typing |

|---|---|---|---|

| GI | |||

| GI.1 | 28.6 | GI.P1 | 2 |

| GI.2 | 1.6 | GI.P2 | 1 |

| GI.3 | 4.6 | GI.P3 | 3 |

| GI.Pa | 1 | ||

| GI.Pd | 7 | ||

| GI.5 | 12.5 | GI.P5 | 9 |

| GII | |||

| GII.2 | 65.9 | GII.P2 | 77 |

| GII.P16 | 1 | ||

| GII.Pe | 3 | ||

| GII.3 | 25.5 | GII.P12 | 14 |

| GII.P21 | 6 | ||

| GII.P16 | 5 | ||

| GII.4 Den Haag | 50 | GII.P4 Den Haag | 1 |

| GII.4 Sydney | 14.5 | GII.Pea | 138 |

| GII.P4 New Orleansa | 30 | ||

| GII.P16a | 71 | ||

| GII.6 | 3.4 | GII.P7 | 5 |

| GII.10 | 25.0 | GII.Pg | 1 |

| GII.13 | 7.0 | GII.P16a | 3 |

| GII.Pe | 1 | ||

| GII.14 | 14.3 | GII.P7a | 2 |

| GII.17 | 36.1 | GII.P17a | 32 |

| GII.Pea | 3 | ||

| GIV | |||

| GIV | 100 | GIV | 1 |

Includes mixed-genotype outbreaks.

FIG 2.

Number of GII.4 Sydney outbreaks from 1 September 2014 through 31 August 2016 submitted to CaliciNet with dual-typing information available. The percentage of all GII.4 outbreaks with polymerase typing information (percent coverage) is presented above the bars for each month. GII.P4 New Orleans; GII.Pe-GII.4 Sydney is a mixed outbreak with some specimens typing as GII.P4 New Orleans-GII.4 Sydney and others typing as GII.Pe-GII.4 Sydney.

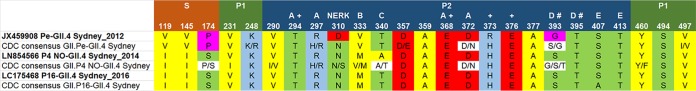

Genetic similarities among GII.P16 polymerase types associated with different norovirus genotypes.

Partial polymerase sequences from viruses from 80 outbreaks were typed as GII.P16 (Table 2; Fig. 3). All GII.P16-GII.4 Sydney sequences clustered with the GII.P16-GII.4 Sydney virus detected in Japan in 2016 (29). Interestingly, GII.P16 sequences of GII.2 viruses clustered closely (>98% nucleotide sequence identity) with the GII.P16 sequences of the GII.4 Sydney viruses, whereas GII.P16 sequences of GII.3 and GII.13 viruses formed distinctly separate clades (Fig. 3). Specific nucleotide changes were observed among the partial polymerase sequences of GII.P16 clades, but only one amino acid change (K to R at position 1646 of the complete ORF1 amino acid sequence) was detected among 17 (8.2%) GII.P16-GII.4 Sydney outbreaks. The amino acid change did not occur in any of the other GII.P16 polymerases, including those among GII.2 genotypes (data not shown). The GII.P16 polymerase sequences of GII.16 and GII.17 viruses formed a clade separate from the GII.P16 sequences identified in our study (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis of GII.P16 polymerase sequences (172 nucleotides) from GII.2, GII.3, GII.4 Sydney, and GII.13 outbreaks in CaliciNet for the period 2013 to 2016. Bootstrap support is indicated (percentage from 500 replicates) with values below 50% hidden. Evolutionary distances were computed using the Kimura two-parameter method with rate variation among sites modeled with a gamma distribution (shape parameter, 0.55). This substitution model was determined to be the best fit, producing the lowest BIC (Bayesian information criterion) and Akaike information criterion (corrected) scores, as determined by the maximum likelihood model testing tool (MEGA, version 7.0.18). Reference strains are represented by their GenBank accession numbers and indicated with filled circles. Sequences obtained in this study are indicated as follows: ▲, GII.4 Sydney; △, GII.2; ◽, GII.3; ■, GII.13.

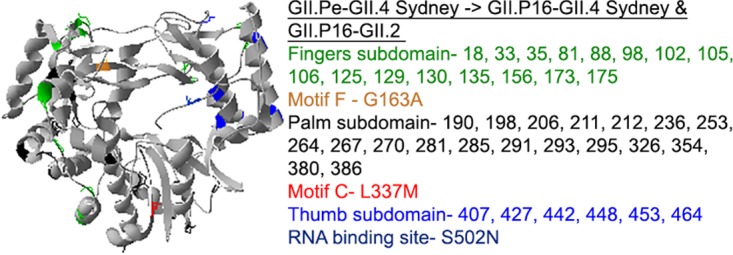

NGS and three-dimensional modeling showed key amino acid substitutions in the novel GII.P16 polymerase protein.

We obtained nearly full-length sequences of 30 specimens from 20 outbreaks (one GII.Pe-GII.4 Sydney, five GII.4 New Orleans-GII.4 Sydney, six GII.P16-GII.4 Sydney, five GII.P16-GII.2, one GII.P2-GII.2, and four GII.P16-GII.13 outbreaks, two of which were mixed-genotype outbreaks). Of these, seven nearly full-length complete coding sequences were submitted to GenBank. Multiple amino acid substitutions were observed when the GII.Pe and GII.P16 polymerases of GII.4 Sydney viruses were compared with reference sequences for GII.Pe-GII.4 Sydney, GII.P16-GII.3, and GII.P16-GII.13 (GenBank accession numbers JX459908, KF895841, and KM036380, respectively) (Fig. 4). Fitting these amino acid changes to the three-dimensional crystal structure of a human norovirus polymerase showed key amino acid changes within motifs F (G163A) and C (L337M) and at the RNA binding site (S502N), among other changes within the fingers, palm, and thumb subdomains (Fig. 4). All of the changes to the GII.P16-GII.4 Sydney polymerase were also present in the GII.P16-GII.2 polymerase. When the novel GII.P16 polymerase was compared to ancestral GII.P16 polymerases of GII.3 and GII.13 viruses, 6 amino acid (aa) substitutions were observed (at positions 173 and 175 of the fingers subdomain and at positions 293, 332, 357, and 360 of the palm subdomain) (data not shown).

FIG 4.

Ribbon structure (PDB accession number 1SH0) indicating amino acid changes to the polymerase of GII.Pe-GII.4 Sydney resulting in the GII.P16 polymerase of GII.4 Sydney and GII.2 genotypes detected in the United States as early as 2015. Colors indicate the subdomains and motifs where the amino acid changes reside in the three-dimensional structure and correspond to those outlined in the text box.

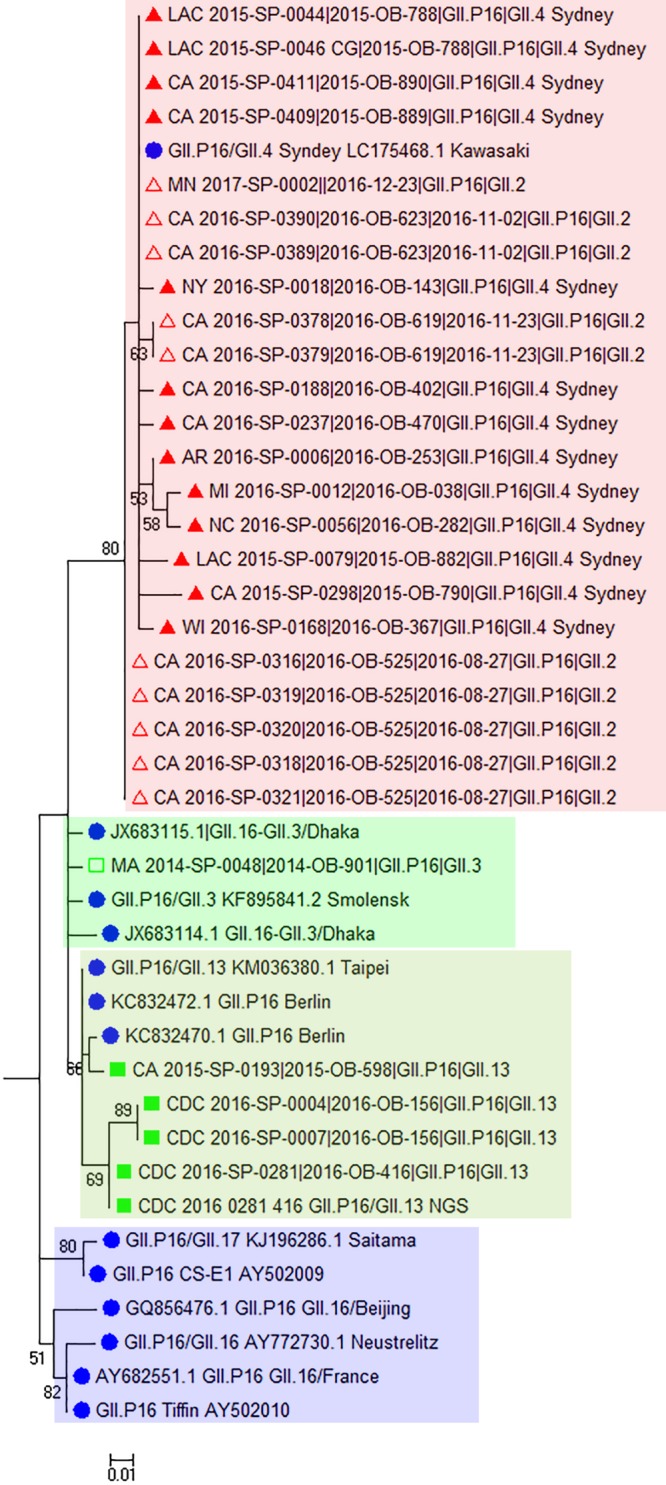

Characterization of antigenic regions of VP1 of recombinant GII.4 Sydney viruses.

Consensus sequences of key amino acid residues within VP1 were created using specimens from 23 outbreaks with complete GII.4 Sydney VP1 sequences (5 GII.Pe, 8 GII.P4 New Orleans, and 12 GII.P16 outbreaks) and 36 outbreaks (19 GII.Pe, 4 GII.P4 New Orleans, and 13 GII.P16 outbreaks) for which P2 sequences were available (Fig. 5). For amino acids under positive selection, only the amino acid at position 373 changed among the different GII.4 Sydney viruses (R373H). Amino acids T294 and E368 of epitope A remained unchanged, but R297H fluctuated among GII.Pe and GII.P4 New Orleans viruses. At position 393 of epitope D (corresponding with HBGA binding site 2), amino acids fluctuated among the GII.4 viruses, while position 395 remained unchanged. Few changes were observed for amino acids of epitope E. The NERK motif (aa 310, 316, 484, and 493) that regulates access to epitope F (30) was conserved for all GII.4 viruses of this study although an N310S substitution was observed for about half of those with a GII.P4 New Orleans polymerase.

FIG 5.

Specific amino acid changes, compared to reference strains, within VP1 corresponding to sites under positive selection, antibody recognition epitopes, or HBGA binding sites for three GII.4 Sydney viruses in circulation from 2013 to 2016 in the United States. Consensus sequences were derived by an alignment of all GII.4 Sydney specimens for which complete VP1 sequences or P2 region sequences were available. Epitope binding regions A, B, C, D, and E and the NERK motif that blocks access to epitope F are indicated. +, amino acid sites under positive selection; #, sites within HBGA binding site 2. Colors indicate amino acid category, as follows: yellow, hydrophobic; green, uncharged; blue, positively charged; red, negatively charged; purple, special. NO, New Orleans.

DISCUSSION

From 1 September 2013 to 31 August 2016, 2,715 norovirus outbreaks were reported to CaliciNet. A novel GII.P16-GII.4 Sydney recombinant virus first detected in November 2015 became the predominant norovirus genotype in the winter of 2015 to 2016, causing over 29% of all norovirus outbreaks. This novel GII.P16 polymerase was >98% identical to the polymerase of GII.2 viruses detected in the United States in 2016 but >5% different from the GII.P16 polymerases detected among GII.3 and GII.13 strains.

The percentage of GII.4 outbreaks in 2013 to 2016 was lower than in previous years. GII.4 Sydney viruses caused over 58% of outbreaks in this period in contrast to 72% in 2009 to 2012 (8). Non-GII.4 genotypes that caused 5.4% to 16.8% of outbreaks in a single year included GI.3, GI.5, GII.2, GII.3, GII.6, GII.13, and GII.17 Kawasaki 308. These genotypes are different from the GI.6, GII.1, and GII.12 genotypes that caused a higher than usual number of outbreaks in the United States in 2009 to 2013 (8). Despite the emergence and predominance of GII.17 Kawasaki 308 noroviruses throughout Asia beginning in the winter of 2014 to 2015 (31–33), this genotype caused only 10.4% of the U.S. outbreaks in 2015 to 2016. One outbreak each was reported for the very rare GIV and the tentative novel GII genotype previously detected exclusively in sporadic cases or sewage samples (34, 35).

Dual typing of norovirus strains showed norovirus genotypes with multiple polymerase types. GII.4 Sydney was associated primarily with GII.Pe until 2015 when the GII.P16-GII.4 Sydney viruses emerged and caused 61.5% of the outbreaks in 2015 to 2016. A GII.P4 New Orleans-GII.4 Sydney virus which has been reported by others (36–39) also caused 1.1% of all outbreaks. The majority of the GII.3 viruses had either a GII.P12 or GII.P21 (formerly GII.Pb) polymerase, as has been described previously (15, 40–42), but GII.P16-GII.3 viruses were also found. GII.2 viruses were primarily associated with a GII.P2 polymerase, but GII.Pe-GII.2 and GII.P16-GII.2 were also detected. All GII.17 Kawasaki 308 viruses carried GII.P17 polymerases, which is consistent with strains reported widely in Asia (32, 43). A GII.Pe-GII.17 virus sharing common ancestry with GII.17 viruses dating back to 1966 was also found (32).

Interestingly, the GII.P16 sequences shared by GII.2 and GII.4 Sydney genotypes were nearly identical to the GII.P16-GII.4 Sydney sequences reported in Japan in January of 2016 (29) and in coastal waters impacted by sewage in China (44). GII.2, GII.3, GII.10, GII.12, GII.13, and GII.17 viruses are known to harbor GII.P16 polymerases. GII.P16-GII.2 viruses reported previously in China, Japan, and Australia/New Zealand (16, 40, 45, 46) are genetically distinct from the recently emerging GII.P16-GII.2 viruses that caused a sharp increase in the number of norovirus infections in Germany and China in late 2016 (47, 48). This novel GII.P16-GII.2 recombinant virus caused at least seven outbreaks in the United States in 2016 as early as August. While GII.P16 polymerases associated with different GII capsids have circulated for decades (17, 18, 42, 49–54) and caused occasional outbreaks (16, 55, 56), the GII.P16 polymerase associated with GII.4 Sydney and GII.2 genotypes appears to have made these viruses evolve toward greater transmissibility.

High error rates among low-fidelity RNA polymerases drive intrahost diversity, a feature important for viral fitness, evolution, and pathogenesis (57). There is evidence that epidemic GII.4 variants have historically evolved through both antigenic drift and recombination at the ORF1-ORF2 junction, resulting in acquisition of a new polymerase (21, 25). Recombination resulting in polymerase switching is also an important mechanism for the evolution of GII.3 genotypes (15). It has long been hypothesized that the increased transmissibility of pandemic GII.4 viruses is due at least partially to their polymerases having lower fidelity than those of nonpandemic variants (58). Indeed, the emergent GII.17 Kawasaki 308 viruses that recently temporarily replaced GII.4 Sydney 2012 viruses in Asia had a polymerase with a higher error rate than the polymerases of GII.4 viruses circulating since the 1970s (31). In further support for this hypothesis, a variant of murine norovirus encoding a high-fidelity polymerase was transmitted less efficiently than the wild-type murine norovirus among mice, demonstrating that the polymerase fidelity of noroviruses can impact their transmission (59). However, it is still too early to conclude if the recently emerging viruses harboring similar GII.P16 polymerases (GII.P16-GII.4 Sydney and GII.P16-GII.2) are due to changes in the polymerase or other nonstructural proteins encoded by ORF1. Future studies are also needed to determine what structural differences contemporary GII.P16 polymerases have gained and what is the functional role of these changes.

In the current study, antigenic sites of VP1 were not drastically changed due to polymerase switching. The GII.Pe-GII.4 Sydney viruses had a high amino acid sequence similarity with those containing GII.P4 New Orleans and GII.P16 polymerases. Epitopes A and D are particularly important vaccine targets as antibodies directed to these epitopes provide a physical barrier for HBGA blockade (30, 60), which is correlated with a reduced frequency of moderate to severe vomiting or diarrhea following GII.4 norovirus infection (61). Epitope A amino acid sequences from the three GII.4 Sydney viruses found in this study fluctuated only at positions 297 and 372; R297H and D372N were noted for some of the GII.4 viruses harboring GII.Pe and GII.P4 New Orleans polymerases. Within epitope D, which includes amino acids directly involved in HBGA binding, variability occurred only at position 393. Amino acid fluctuation among these sites reflects those of the GII.4 New Orleans viruses (62). Not surprisingly, there was more sequence variability among GII.4 viruses harboring the GII.Pe and GII.P4 New Orleans polymerases in this study which have been circulating much longer than viruses with the GII.P16 polymerase. Taken together, the three GII.4 Sydney viruses identified in our study appear to be antigenically similar, in contrast with findings reported elsewhere (39). If these in silico findings are bona fide and if polymerase switching occurs without significant antigenic variation, vaccine development efforts may become more complicated. It would indicate that factors other than population herd immunity must be considered for a successful norovirus vaccine. Alternatively, the recombinant viruses we describe may be intermediary viruses affecting naive pockets in the population, and acquisition of a new (lower-fidelity) polymerase is needed for capsid evolution and emergence of the next antigenic GII.4 variant.

A limitation of this study is that dual-typing data were not available for all outbreak specimens since polymerase typing is not yet routinely performed by all CaliciNet laboratories. We therefore requested specimens from 20% of outbreaks caused by genotypes (GII.2, GII.3, GII.4 Sydney, GII.13, and GII.17) known to harbor GII.P16 polymerases. We were successful in obtaining dual-typing information for at least 10% of these outbreaks occurring primarily in the last 2 years of the study, as few laboratories retained specimens from the 2013-2014 season. The current study highlights the importance of dual typing for a more complete understanding of the molecular epidemiology of noroviruses, and hence P-C testing is currently being implemented as a standard protocol for all CaliciNet laboratories.

In this first description and analysis of CaliciNet data using the dual-typing assay, recombination among noroviruses was frequently detected. Acquisition of the GII.P16 polymerase and/or associated nonstructural proteins appears to be the impetus for the predominance of GII.P16-GII.4 Sydney viruses in 2015 to 2016. GII.2 and GII.4 Sydney viruses with the GII.P16 polymerase also predominated in the 2016-2017 season in the United States (https://www.cdc.gov/norovirus/reporting/calicinet/data.html), indicating a fitness advantage occurring with polymerase switching. Greater access to next-generation sequencing technologies and the recent development of cell culture propagation methods for human noroviruses (63, 64) will greatly enhance our abilities to determine the importance of nonstructural protein changes on norovirus fitness. Continued molecular surveillance, including typing of both polymerase and capsid genes, is important for monitoring emerging norovirus strains in our continued efforts to reduce the overall burden of norovirus disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

CaliciNet.

Epidemiologic and genotype information for confirmed norovirus outbreaks was submitted to CaliciNet by participating state and local public health laboratories in the United States, as described previously (8, 27). In CaliciNet, norovirus surveillance years are defined as starting on 1 September and ending on 31 August. The median number of genotype-confirmed specimens from each outbreak was 2 (range, 1 to 18 specimens; interquartile range, 2 to 3 specimens).

Selection of specimens.

We requested specimens and/or further laboratory testing to be performed at CaliciNet laboratories for outbreaks meeting certain inclusion criteria in order to capture the prevalence of GII.P16 polymerases among noroviruses in the United States. Specifically, to gather dual-typing (polymerase and capsid) information for norovirus genotypes in the United States, we validated and used a new polymerase-capsid (P-C) assay which combines previously published assays targeting regions B and C (see below). Inclusion criteria for additional specimen testing were outbreaks caused by the following: (i) GII.4 genotypes that differed by greater than 2% nucleotide difference in region C from known GII.4 strains, (ii) non-GII.4 genotypes known to be associated with GII.P16 polymerases, and (iii) mixed-genotype outbreaks. Among this selection, 20% of outbreaks occurring within each U.S. census region (West, Midwest, South, and Northeast), as well as within each season, early, middle, and late, corresponding with January to April, May to August, and September to December, respectively, were sought for P-C testing. The intent for requesting 20% of outbreaks was that at least 10% of outbreaks would have specimens available for analysis. For some outbreaks (primarily those caused by GII.2 and GII.4 Sydney viruses), full-length genome sequencing and complete sequencing of the VP1 or P2 region sequencing were performed. Sequences from five additional GII.P16-GII.2 outbreaks from 1 September to 31 December 2016 were also included in our phylogenetic and structural analysis of the GII.P16 polymerase since only one GII.P16-GII.2 outbreak had been submitted to CaliciNet prior to 1 September 2016. Complete VP1 and full-length norovirus genome sequencing was performed using Sanger and next-generation sequencing (NGS) approaches, respectively.

Norovirus RT-PCR assays.

Real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) targeting the ORF1/ORF2 overlap region was performed initially on all outbreak specimens by CaliciNet laboratories. The current standard CaliciNet detection protocol is a multiplex real-time assay (65, 66) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) using an Ag-Path kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) without detection enhancer, 400 nM each oligonucleotide primer (Cog1F and Cog1R for GI viruses; Cog2F and Cog2R for GII viruses) (27), and 200 nM each probe (Ring 1E, FAM-TGG ACA GGR GAY CGC-MGBNFQ, where FAM is 6-carboxyfluorescein and MGBNFQ is minor groove binder and nonfluorescent quencher [64, 65]; Ring 2 [27]) as well as 100 nM each primer and probe (MS2.F/R and MS2.P) for an MS2 bacteriophage internal amplification and extraction control (MS2; ATCC 15597-B1) (67). Cycling conditions were performed as follows: reverse transcription for 10 min at 45°C, followed by denaturation for 10 min at 95°C, and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min each. Cycle threshold (CT) cutoff values of 35 and 37 were used as the limits of detection for GI and GII real-time results, respectively. Positive samples were primarily genotyped using a modified region C protocol which included (1 μM each) G1SKF/R oligonucleotide primers for GI and oligonucleotide primers Ring 2 (TGG GAG GGC GAT CGC AAT CT) and G2SKR for GII using cycling parameters as described previously (27), with the exceptions that the denaturation (95°C) and primer annealing (50°C) phases were 1 min each and the final extension at 72°C was for 10 min. Region C-negative samples were genotyped using a region D protocol as described previously (27). A novel RT-PCR (P-C typing assay) was performed by using a combination of previously published oligonucleotide primers: primers MON432 (TGG ACI CGY GGI CCY AAY CA) and G1SKR (CCA ACC CAR CCA TTR TAC A) for GI viruses; primers MON431 (TGG ACI AGR GGI CCY AAY CA) and G2SKR (CCR CCN GCA TRH CCR TTR TAC AT) for GII viruses (12, 28). For GI viruses, the expected PCR product size is ∼543 bp, and for GII viruses it is ∼557 bp. Viral nucleic acid was extracted from 10% clarified fecal suspensions prepared in phosphate-buffered saline using a MagMax-96 Viral RNA Isolation kit (Ambion, Foster City, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions, on an automated KingFisher extractor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Qiagen One-Step RT-PCR (Qiagen) master mix was used with 20 U of RNase inhibitor (Applied Biosystems) with the following cycling conditions: 30 min at 42°C, 15 min at 95°C, and 40 cycles of 95°C, 50°C, and 72°C for 1 min each, followed by 10 min at 72°C. GII.4 specimens were also tested in the P2 region using primers EVP2F and EVP2R (674-bp product size) as described previously (8). Complete VP1 genes of GII.4 viruses were amplified by overlapping RT-PCR assays using a Qiagen One-Step RT-PCR kit and oligonucleotide primer set Ring2 (TGG GAG GGC GAT CGC AAT CT) and RingP2R-1 (GGG AAY CTT GAR TTG GTC AT) and primer set EVF9-1 (AAT GAA CCY CAA CAA TG) and PanGIIR1 (GTC CAG GAG TCC AAA A). Cycling conditions included reverse transcription for 30 min at 42°C, denaturation for 15 min at 95°C, and 40 cycles of 94°C (30 s), 50°C (30 s), and 68°C (2 min), followed by a final extension for 10 min at 68°C.

PCR products were visualized on a 2% agarose gel (Seakem-ME, Lonza, Allendale, NJ, USA) containing Gel Red (Biotium, Fremont, CA, USA) and gel purified by an ExoSAP-IT (Affymetrix, USB, Cleveland, OH, USA) or QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and Sanger sequencing (Eurofins MWG Operon, Louisville, KY, USA).

Next-generation sequencing to obtain full-length norovirus genomes.

Viral RNA extraction was performed using a QIAmp Viral RNA minikit extraction kit (Qiagen) with nuclease and DNase treatment as described previously (68). After random PCR amplification, cDNA libraries were generated using an Illumina Nextera XT DNA Library Prep kit, and sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq platform (69, 70). Raw reads were preprocessed by adaptor and primer removal, host sequence subtraction, sequence deduplication, and quality filtering with a Phred score cutoff of 30 before de novo assembly was performed using SPAdes, version 3.7 (71), with multiple k-mer lengths. A recruitment mapping approach utilizing the internal algorithm in the Geneious, version 9.1.6, software package (Biomatters Inc. Newark, NJ) resolved the final consensus sequence for each specimen.

Data analysis.

CaliciNet genotyping and epidemiological data (outbreak date and location [state or cruise ship]) were downloaded and imported into MS Excel (2016) for basic data manipulation and graphing, and graphing was performed with Origin 2017 software. Statistical analysis was performed in JMP, version 13.0.0 (SAS). Pearson's chi-square test was also used to determine monthly quarters (January to March, April to June, July to September, October to December) for which the proportion of outbreaks that occurred each year differed from the hypothetical proportion of 25%. Genotypes were assigned by phylogenetic analysis using the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA) with reference sequences used by CaliciNet (27) for capsid typing and reference strains used by the Norovirus Typing Tool, version 2.0, for polymerase typing (10, 72). Multiple alignments using MUSCLE and phylogenetic analysis by the neighbor-joining method were performed using MEGA, version 7 (73–75). The MEGA maximum likelihood model selection tool was used to determine the best model for branch support using the Bayesian information criterion for analysis, which was determined to be the Kimura two-parameter method with rate variation among sites modeled with a gamma distribution (K2+G) (76). Amino acid substitutions occurring within the complete polymerase region were visualized by overlay on the three-dimensional crystal structure of Norwalk virus polymerase (Protein Data Bank accession number 1SH0) (77) using DeepView/Swiss-PdbViewer, version 4.1.0 (Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics).

Accession number(s).

Sequences derived in this study were deposited in the GenBank under accession numbers KY865306, KY865307, and KY947546 to KY947550.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Annie Phillips and Hannah Browne for excellent assistance with dual-typing of norovirus specimens. We gratefully acknowledge the CaliciNet members who contributed to the data presented in the manuscript: Courtney Chesnutt and Nicholas Switzer (Alabama Department of Public Health, Bureau of Clinical Laboratories); Cheng Yang (Arkansas Department of Health, Public Health Laboratory); Chao-Yang Pan, Tasha Padilla, and Thalia Huynh (California Department of Public Health); Julia Wolfe, Kathryn Siemers, and Rina Tjiptahadi (Orange County Public Health Laboratory, CA); Taylor Mundt, Eduardo Ramos, and Peijia Chen (Los Angeles County, Public Health Laboratory, CA); Justin Nucci and Mary-Kate Cichon (Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment); Horng-Yuan Kan (Washington, DC, Public Health Laboratory); Gregory Hovan (Delaware Public Health Laboratories); Jacquelina Woods (U.S. FDA); Lea A. Heberlein-Larson and Marshall Cone (Florida Department of Health, Bureau of Public Health Laboratories, Tampa, FL); Precilia Calimlim, Cheryl-Lynn Daquip, and Kris Rimando (Hawaii Department of Health); Kari Getz, Lindsey Catlin, and Amanda Bruesch (Idaho Bureau of Laboratories); Cassandra Campion and Melissa Hindenlang (Indiana State Department of Health Laboratories); Beth Anna Leigh Young (Kentucky State Health Laboratory); Erika Buzby, Pinal Patel, and Brandon Sabina (Massachusetts Department of Public Health); Jonathan Johnston, Julie Haendiges, and Eric Keller (Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Laboratories Administration); Laura Mosher, Victoria Vavricka, and Kevin Rodeman (Michigan Department of Community Health, Bureau of Laboratories); Elizabeth Cebelinski, Ginette Dobbins, and Mary Elizabeth Horn (Minnesota Department of Health, Infectious Disease Laboratory); Shadia Rath, Katja Manninen, and Robbie Li Ann Hall (North Carolina State Laboratory Of Public Health); Xinglu Zhang, Fengxiang Gao, and Xinglu Zhang (New Hampshire Public Health Laboratories, Department of Health and Human Services); Kendra Pesko and Charles Yaple (New Mexico Department of Health, Scientific Laboratory Division); Patrick Bryant and Daryl M. Lamson (New York State Department of Health, Wadsworth Center); Rebekah Carman, Rosemary Hage, Lai Ming Woo, Eric Brandt, and Jade Mowery (Ohio Department of Health Laboratory); James M. Terry, Laura Flint, Vanda Makris, and Laura J. Tsaknaridis (Oregon State Public Health Laboratory); Andrea Maloney and Andrea Licata (South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control); Linda S. Thomas, Christina Moore, and Amy M. Woron (Tennessee Department of Health, Laboratory Services); Chun Wang and Jenny Zhang (Texas Department of State Health Services); Leigh-Emma Lion, Patricia Croscutt, and Mary Kathryne Dickinson (Virginia Division of Consolidated Laboratory Services); Valarie Devlin and Jessica Chenette (Vermont Department of Health Laboratory); Tim Davis, T. J. Whyte, Richard Griesser, and Tonya Danz (Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene); Jose Navidad (City of Milwaukee Health Department, WI); and Rob Christensen (Wyoming Public Health Laboratory).

This study was partially supported by a grant from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture (2011-68003-30395), by the intramural food safety program and the Advanced Molecular Detection program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This research was also supported in part by fellowships from the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the CDC.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00455-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed SM, Hall AJ, Robinson AE, Verhoef L, Premkumar P, Parashar UD, Koopmans M, Lopman BA. 2014. Global prevalence of norovirus in cases of gastroenteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 14:725–730. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70767-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wikswo ME, Kambhampati A, Shioda K, Walsh KA, Bowen A, Hall AJ. 2015. Outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis transmitted by person-to-person contact, environmental contamination, and unknown modes of transmission—United States, 2009–2013. MMWR Surveill Summ 64(SS12):1–16. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6412a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall AJ, Wikswo ME, Manikonda K, Roberts VA, Yoder JS, Gould LH. 2013. Acute gastroenteritis surveillance through the National Outbreak Reporting System, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 19:1305–1309. doi: 10.3201/eid1908.130482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Payne DC, Vinje J, Szilagyi PG, Edwards KM, Staat MA, Weinberg GA, Hall CB, Chappell J, Bernstein DI, Curns AT, Wikswo M, Shirley SH, Hall AJ, Lopman B, Parashar UD. 2013. Norovirus and medically attended gastroenteritis in U.S. children. N Engl J Med 368:1121–1130. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1206589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopman BA, Steele D, Kirkwood CD, Parashar UD. 2016. The vast and varied global burden of norovirus: prospects for prevention and control. PLoS Med 13:e1001999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kambhampati A, Koopmans M, Lopman BA. 2015. Burden of norovirus in healthcare facilities and strategies for outbreak control. J Hosp Infect 89:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartsch SM, Lopman BA, Ozawa S, Hall AJ, Lee BY. 2016. Global economic burden of norovirus gastroenteritis. PLoS One 11:e0151219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vega E, Barclay L, Gregoricus N, Shirley SH, Lee D, Vinje J. 2014. Genotypic and epidemiologic trends of norovirus outbreaks in the United States, 2009 to 2013. J Clin Microbiol 52:147–155. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02680-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroneman A, Vega E, Vennema H, Vinje J, White PA, Hansman G, Green K, Martella V, Katayama K, Koopmans M. 2013. Proposal for a unified norovirus nomenclature and genotyping. Arch Virol 158:2059–2068. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1708-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vinje J. 2015. Advances in laboratory methods for detection and typing of norovirus. J Clin Microbiol 53:373–381. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01535-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vinje J, Koopmans MP. 1996. Molecular detection and epidemiology of small round-structured viruses in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in the Netherlands. J Infect Dis 174:610–615. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.3.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson AD, Garrett VD, Sobel J, Monroe SS, Fankhauser RL, Schwab KJ, Bresee JS, Mead PS, Higgins C, Campana J, Glass RI. 2001. Multistate outbreak of Norwalk-like virus gastroenteritis associated with a common caterer. Am J Epidemiol 154:1013–1019. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.11.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vennema H, de Bruin E, Koopmans M. 2002. Rational optimization of generic primers used for Norwalk-like virus detection by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Virol 25:233–235. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(02)00126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bull RA, White PA. 2011. Mechanisms of GII.4 norovirus evolution. Trends Microbiol 19:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahar JE, Bok K, Green KY, Kirkwood CD. 2013. The importance of intergenic recombination in norovirus GII.3 evolution. J Virol 87:3687–3698. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03056-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim KL, Hewitt J, Sitabkhan A, Eden JS, Lun J, Levy A, Merif J, Smith D, Rawlinson WD, White PA. 2016. A Multi-Site study of Norovirus Molecular Epidemiology in Australia and New Zealand, 2013–2014. PLoS One 11:e0145254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mans J, Murray TY, Nadan S, Netshikweta R, Page NA, Taylor MB. 2016. Norovirus diversity in children with gastroenteritis in South Africa from 2009 to 2013: GII.4 variants and recombinant strains predominate. Epidemiol Infect 144:907–916. doi: 10.1017/S0950268815002150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medici MC, Tummolo F, Martella V, Giammanco GM, De Grazia S, Arcangeletti MC, De Conto F, Chezzi C, Calderaro A. 2014. Novel recombinant GII.P16_GII.13 and GII.P16_GII.3 norovirus strains in Italy. Virus Res 188:142–145. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siebenga JJ, Vennema H, Zheng DP, Vinje J, Lee BE, Pang XL, Ho EC, Lim W, Choudekar A, Broor S, Halperin T, Rasool NB, Hewitt J, Greening GE, Jin M, Duan ZJ, Lucero Y, O'Ryan M, Hoehne M, Schreier E, Ratcliff RM, White PA, Iritani N, Reuter G, Koopmans M. 2009. Norovirus illness is a global problem: emergence and spread of norovirus GII.4 variants, 2001–2007. J Infect Dis 200:802–812. doi: 10.1086/605127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green KY. 2013. Caliciviridae: the noroviruses, p 586–608. In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Cohen JI, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Rancaniello VR, Roizman B (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 21.White PA. 2014. Evolution of norovirus. Clin Microbiol Infect 20:741–745. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Debbink K, Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Costantini V, Beltramello M, Corti D, Swanstrom J, Lanzavecchia A, Vinje J, Baric RS. 2013. Emergence of new pandemic GII.4 Sydney norovirus strain correlates with escape from herd immunity. J Infect Dis 208:1877–1887. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Pendu J, Nystrom K, Ruvoen-Clouet N. 2014. Host-pathogen co-evolution and glycan interactions. Curr Opin Virol 7:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donaldson EF, Lindesmith LC, Lobue AD, Baric RS. 2010. Viral shape-shifting: norovirus evasion of the human immune system. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:231–241. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eden JS, Tanaka MM, Boni MF, Rawlinson WD, White PA. 2013. Recombination within the pandemic norovirus GII.4 lineage. J Virol 87:6270–6282. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03464-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leshem E, Wikswo M, Barclay L, Brandt E, Storm W, Salehi E, DeSalvo T, Davis T, Saupe A, Dobbins G, Booth HA, Biggs C, Garman K, Woron AM, Parashar UD, Vinje J, Hall AJ. 2013. Effects and clinical significance of GII.4 Sydney norovirus, United States, 2012–2013. Emerg Infect Dis 19:1231–1238. doi: 10.3201/eid1908.130458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vega E, Barclay L, Gregoricus N, Williams K, Lee D, Vinje J. 2011. Novel surveillance network for norovirus gastroenteritis outbreaks, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 17:1389–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kojima S, Kageyama T, Fukushi S, Hoshino FB, Shinohara M, Uchida K, Natori K, Takeda N, Katayama K. 2002. Genogroup-specific PCR primers for detection of Norwalk-like viruses. J Virol Methods 100:107–114. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(01)00404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsushima Y, Shimizu T, Ishikawa M, Komane A, Okabe N, Ryo A, Kimura H, Katayama K, Shimizu H. 2016. Complete genome sequence of a recombinant GII.P16-GII.4 norovirus detected in Kawasaki City, Japan, in 2016. Genome Announc 4:e01099-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01099-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Beltramello M, Pintus S, Corti D, Swanstrom J, Debbink K, Jones TA, Lanzavecchia A, Baric RS. 2014. Particle conformation regulates antibody access to a conserved GII.4 norovirus blockade epitope. J Virol 88:8826–8842. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01192-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan MC, Lee N, Hung TN, Kwok K, Cheung K, Tin EK, Lai RW, Nelson EA, Leung TF, Chan PK. 2015. Rapid emergence and predominance of a broadly recognizing and fast-evolving norovirus GII.17 variant in late 2014. Nat Commun 6:10061. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu J, Fang L, Zheng H, Lao J, Yang F, Sun L, Xiao J, Lin J, Song T, Ni T, Raghwani J, Ke C, Faria NR, Bowden TA, Pybus OG, Li H. 2016. The evolution and transmission of epidemic GII.17 noroviruses. J Infect Dis 214:556–564. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Graaf M, van Beek J, Vennema H, Podkolzin AT, Hewitt J, Bucardo F, Templeton K, Mans J, Nordgren J, Reuter G, Lynch M, Rasmussen LD, Iritani N, Chan MC, Martella V, Ambert-Balay K, Vinje J, White PA, Koopmans MP. 2015. Emergence of a novel GII.17 norovirus—end of the GII.4 era? Euro Surveill 20:21178. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2015.20.26.21178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitajima M, Rachmadi AT, Iker BC, Haramoto E, Gerba CP. 2016. Genetically distinct genogroup IV norovirus strains identified in wastewater. Arch Virol 161:3521–3525. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-3036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ao YY, Yu JM, Li LL, Jin M, Duan ZJ. 2014. Detection of human norovirus GIV.1 in China: a case report. J Clin Virol 61:298–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fonager J, Barzinci S, Fischer TK. 2013. Emergence of a new recombinant Sydney 2012 norovirus variant in Denmark, 26 December 2012 to 22 March 2013. Euro Surveill 18:20506. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.25.20506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong TH, Dearlove BL, Hedge J, Giess AP, Piazza P, Trebes A, Paul J, Smit E, Smith EG, Sutton JK, Wilcox MH, Dingle KE, Peto TE, Crook DW, Wilson DJ, Wyllie DH. 2013. Whole-genome sequencing and de novo assembly identifies Sydney-like variant noroviruses and recombinants during the winter 2012/2013 outbreak in England. Virol J 10:335. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martella V, Medici MC, De Grazia S, Tummolo F, Calderaro A, Bonura F, Saporito L, Terio V, Catella C, Lanave G, Buonavoglia C, Giammanco GM. 2013. Evidence for recombination between pandemic GII.4 norovirus strains New Orleans 2009 and Sydney 2012. J Clin Microbiol 51:3855–3857. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01847-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruggink L, Catton M, Marshall J. 2016. A norovirus intervariant GII.4 recombinant in Victoria, Australia, June 2016: the next epidemic variant? Euro Surveill 21:30353. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.39.30353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang YH, Zhou DJ, Zhou X, Yang T, Ghosh S, Pang BB, Peng JS, Liu MQ, Hu Q, Kobayashi N. 2012. Molecular epidemiology of noroviruses in children and adults with acute gastroenteritis in Wuhan, China, 2007–2010. Arch Virol 157:2417–2424. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chhabra P, Payne DC, Szilagyi PG, Edwards KM, Staat MA, Shirley SH, Wikswo M, Nix WA, Lu X, Parashar UD, Vinje J. 2013. Etiology of viral gastroenteritis in children <5 years of age in the United States, 2008–2009. J Infect Dis 208:790–800. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mans J, Murray TY, Taylor MB. 2014. Novel norovirus recombinants detected in South Africa. Virol J 11:168. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsushima Y, Ishikawa M, Shimizu T, Komane A, Kasuo S, Shinohara M, Nagasawa K, Kimura H, Ryo A, Okabe N, Haga K, Doan YH, Katayama K, Shimizu H. 2015. Genetic analyses of GII.17 norovirus strains in diarrheal disease outbreaks from December 2014 to March 2015 in Japan reveal a novel polymerase sequence and amino acid substitutions in the capsid region. Euro Surveill 20:21173. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2015.20.26.21173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi YS, Koo ES, Kim MS, Choi JD, Shin Y, Jeong YS. 24 January 2017. Re-emergence of a GII.4 norovirus Sydney 2012 variant equipped with GII.P16 RdRp and its predominance over novel variants of GII.17 in South Korea in 2016. Food Environ Virol doi: 10.1007/s12560-017-9278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iritani N, Kaida A, Abe N, Sekiguchi J, Kubo H, Takakura K, Goto K, Ogura H, Seto Y. 2012. Increase of GII.2 norovirus infections during the 2009-2010 season in Osaka City, Japan. J Med Virol 84:517–525. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Motomura K, Boonchan M, Noda M, Tanaka T, Takeda N. 2016. Norovirus epidemics caused by new GII.2 chimera viruses in 2012–2014 in Japan. Infect Genet Evol 42:49–52. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niendorf S, Jacobsen S, Faber M, Eis-Hubinger AM, Hofmann J, Zimmermann O, Hohne M, Bock CT. 2017. Steep rise in norovirus cases and emergence of a new recombinant strain GII.P16-GII.2, Germany, winter 2016. Euro Surveill 22:30447. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.4.30447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu J, Fang L, Sun L, Zeng H, Li Y, Zheng H, Wu S, Yang F, Song T, Lin J, Ke C, Zhang Y, Vinjé J, Li H. 2017. Association of GII.P16-GII.2 recombinant norovirus strain with increased norovirus outbreaks, Guangdong, China, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis 23:7. doi: 10.3201/eid2307.170333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoa-Tran TN, Nakagomi T, Sano D, Sherchand JB, Pandey BD, Cunliffe NA, Nakagomi O. 2015. Molecular epidemiology of noroviruses detected in Nepalese children with acute diarrhea between 2005 and 2011: increase and predominance of minor genotype GII.13. Infect Genet Evol 30:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nahar S, Afrad MH, Matthijnssens J, Rahman MZ, Momtaz Z, Yasmin R, Jubair M, Faruque AS, Choudhuri MS, Azim T, Rahman M. 2013. Novel intergenotype human norovirus recombinant GII.16/GII.3 in Bangladesh. Infect Genet Evol 20:325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arana A, Cilla G, Montes M, Gomariz M, Perez-Trallero E. 2014. Genotypes, recombinant forms, and variants of norovirus GII.4 in Gipuzkoa (Basque Country, Spain), 2009–2012. PLoS One 9:e98875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu X, Han J, Chen L, Xu D, Shen Y, Zha Y, Zhu X, Ji L. 2015. Prevalence and genetic diversity of noroviruses in adults with acute gastroenteritis in Huzhou, China, 2013–2014. Arch Virol 160:1705–1713. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2440-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Medici MC, Tummolo F, Martella V, Chezzi C, Arcangeletti MC, De Conto F, Calderaro A. 2014. Epidemiological and molecular features of norovirus infections in Italian children affected with acute gastroenteritis. Epidemiol Infect 142:2326–2335. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813003373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim JS, Kim HS, Hyun J, Kim HS, Song W. 2015. Molecular epidemiology of human norovirus in Korea in 2013. Biomed Res Int 2015:468304. doi: 10.1155/2015/468304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fumian TM, da Silva Ribeiro de Andrade J, Leite JP, Miagostovich MP. 2016. Norovirus recombinant strains isolated from gastroenteritis outbreaks in southern Brazil, 2004–2011. PLoS One 11:e0145391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Made D, Trubner K, Neubert E, Hohne M, Johne R. 2013. Detection and typing of norovirus from frozen strawberries involved in a large-scale gastroenteritis outbreak in Germany. Food Environ Virol 5:162–168. doi: 10.1007/s12560-013-9118-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deval J, Jin Z, Chuang YC, Kao CC. 29 December 2016. Structure(s), function(s), and inhibition of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of noroviruses. Virus Res doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bull RA, Eden JS, Rawlinson WD, White PA. 2010. Rapid evolution of pandemic noroviruses of the GII.4 lineage. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000831. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arias A, Thorne L, Ghurburrun E, Bailey D, Goodfellow I. 2016. Norovirus polymerase fidelity contributes to viral transmission in vivo. mSphere 3:e00279-16. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00279-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Debbink K, Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Baric RS. 2012. Norovirus immunity and the great escape. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002921. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Atmar RL, Bernstein DI, Lyon GM, Treanor JJ, Al-Ibrahim MS, Graham DY, Vinje J, Jiang X, Gregoricus N, Frenck RW, Moe CL, Chen WH, Ferreira J, Barrett J, Opekun AR, Estes MK, Borkowski A, Baehner F, Goodwin R, Edmonds A, Mendelman PM. 2015. Serological correlates of protection against a GII.4 norovirus. Clin Vaccine Immunol 22:923–929. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00196-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eden JS, Hewitt J, Lim KL, Boni MF, Merif J, Greening G, Ratcliff RM, Holmes EC, Tanaka MM, Rawlinson WD, White PA. 2014. The emergence and evolution of the novel epidemic norovirus GII.4 variant Sydney 2012. Virology 450–451:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jones MK, Watanabe M, Zhu S, Graves CL, Keyes LR, Grau KR, Gonzalez-Hernandez MB, Iovine NM, Wobus CE, Vinje J, Tibbetts SA, Wallet SM, Karst SM. 2014. Enteric bacteria promote human and mouse norovirus infection of B cells. Science 346:755–759. doi: 10.1126/science.1257147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ettayebi K, Crawford SE, Murakami K, Broughman JR, Karandikar U, Tenge VR, Neill FH, Blutt SE, Zeng XL, Qu L, Kou B, Opekun AR, Burrin D, Graham DY, Ramani S, Atmar RL, Estes MK. 2016. Replication of human noroviruses in stem cell-derived human enteroids. Science 353:1387–1393. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park GW, Chhabra P, Vinjé J. 2017. Swab sampling method for the detection of human norovirus on surfaces. J Vis Exp 6:e55205. doi: 10.3791/55205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vinjé J, Gregoricus N, Chhabra P, Barclay L. May 2013. Selective detection of norovirus. US patent WO2013074785A1.

- 67.Rolfe KJ, Parmar S, Mururi D, Wreghitt TG, Jalal H, Zhang H, Curran MD. 2007. An internally controlled, one-step, real-time RT-PCR assay for norovirus detection and genogrouping. J Clin Virol 39:318–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Montmayeur AM, Ng TF, Schmidt A, Zhao K, Magana L, Iber J, Castro CJ, Chen Q, Henderson E, Ramos E, Shaw J, Tatusov RL, Dybdahl-Sissoko N, Endegue-Zanga MC, Adeniji JA, Oberste MS, Burns CC. 2017. High-throughput next-generation sequencing of polioviruses. J Clin Microbiol 55:606–615. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02121-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yu G, Greninger AL, Isa P, Phan TG, Martinez MA, de la Luz Sanchez M, Contreras JF, Santos-Preciado JI, Parsonnet J, Miller S, DeRisi JL, Delwart E, Arias CF, Chiu CY. 2012. Discovery of a novel polyomavirus in acute diarrheal samples from children. PLoS One 7:e49449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Greninger AL, Chen EC, Sittler T, Scheinerman A, Roubinian N, Yu G, Kim E, Pillai DR, Guyard C, Mazzulli T, Isa P, Arias CF, Hackett J, Schochetman G, Miller S, Tang P, Chiu CY. 2010. A metagenomic analysis of pandemic influenza A (2009 H1N1) infection in patients from North America. PLoS One 5:e13381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nurk S, Bankevich A, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Korobeynikov A, Lapidus A, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin A, Sirotkin A, Sirotkin Y, Stepanauskas R, Clingenpeel SR, Woyke T, McLean JS, Lasken R, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2013. Assembling single-cell genomes and mini-metagenomes from chimeric MDA products. J Comput Biol 20:714–737. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2013.0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kroneman A, Vennema H, Deforche K, v d Avoort H, Penaranda S, Oberste MS, Vinje J, Koopmans M. 2011. An automated genotyping tool for enteroviruses and noroviruses. J Clin Virol 51:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. 2016. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saitou N, Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4:406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nei M, Kumar S. 2000. Molecular evolution and phylogenetics. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kimura M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol 16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ng KK, Pendas-Franco N, Rojo J, Boga JA, Machin A, Alonso JM, Parra F. 2004. Crystal structure of Norwalk virus polymerase reveals the carboxyl terminus in the active site cleft. J Biol Chem 279:16638–16645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400584200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.