Abstract

Inactivation of the small guanosine triphosphate–binding protein Ras during receptor signal transduction is mediated by Ras guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase)–activating proteins (RasGAPs). Ten different RasGAPs have been identified and have overlapping patterns of tissue distribution. However, genetic analyses are revealing critical nonredundant functions for each RasGAP in tissue homeostasis and as regulators of disease processes in mouse and man. Here, we discuss advances in understanding the role of RasGAPs in the maintenance of tissue integrity.

Introduction

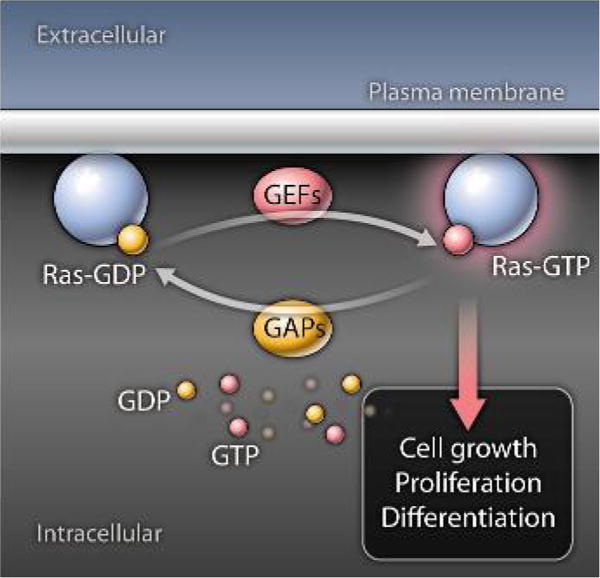

Ras proteins constitute one subset of a large family of evolutionarily conserved monomeric small guanosine triphosphate (GTP)–binding proteins involved in intracellular signal transduction in eukaryotes (1). They are activated by various cell surface receptors in response to ligand binding, whereupon they convey signals that regulate cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation in essentially all cell types. There are three different classical Ras isoforms (H-Ras, K-Ras, and N-Ras), each of which is tethered to the inner leaflet of the cell membrane through prenylation at the C-terminal end. Ras proteins, like all members of the Ras superfamily, function as molecular switches that cycle between inactive guanosine diphosphate (GDP)–bound and active GTP-bound states. During the course of receptor signal transduction, Ras is converted to its active form when one or more Ras guanine nucleotide exchange factor proteins (RasGEFs) is recruited to the membrane (2). RasGEFs dissociate GDP from the Ras guanine nucleotide-binding pocket, which allows Ras to bind GTP, which is present at higher intracellular concentrations than GDP (Fig. 1). In its GTP-bound form, Ras engages Ras effector molecules, which results in the activation of downstream signaling pathways, such as the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), and protein kinase B (PKB) pathways that drive cellular responses in part through modulation of the activity of transcription factors (3, 4).

Fig. 1.

Ras is bound to GDP in its inactive state. RasGEFs dissociate GDP to enable Ras to bind GTP. GTP-bound Ras signals through downstream kinase cascades that promote cell proliferation and differentiation. RasGAPs inactivate Ras by catalyzing GTP hydrolysis, returning Ras to its inactive GDP-bound state.

Ras has only weak intrinsic guanosine triphophatase (GTPase) activity. Therefore efficient conversion of Ras back to its inactive state is dependent upon Ras GTPase-activating proteins (RasGAPs) (2, 5). Through physical interaction with Ras, RasGAPs increase the ability of Ras to hydrolyze GTP by several orders of magnitude. The GAP domain of RasGAPs extends a critical arginine side chain into the Ras active site, which allows the glutamine residue in position 61 of human H-Ras (Gln61) to participate in catalysis (6–8). Mutations at Gln61 or at residues 12 or 13, which alter the orientation of Gln61, prevent GTP hydrolysis, which locks Ras in a permanently “on” state (9, 10). These mutations are found in up to 30% of all human cancers and occur in a much higher percentage of pancreatic cancer and colon cancer (9, 10), which underscores the importance of this cooperative Ras-RasGAP mechanism.

The RasGAP Family: Structure and Signaling-Dependent Membrane Localization

RASA1 and NF1

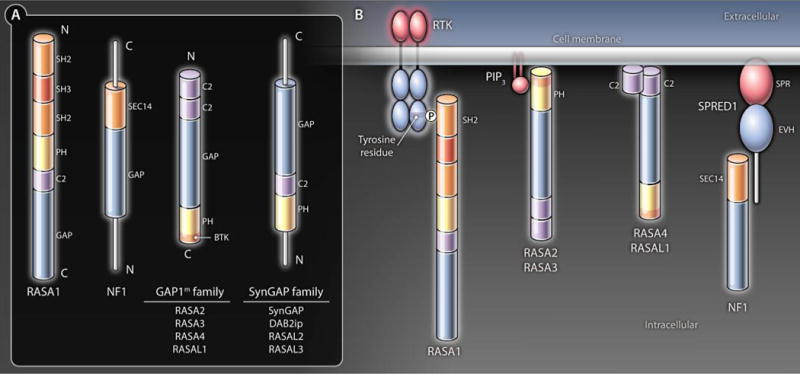

The first RasGAP to be characterized was p120 RasGAP or Ras p21 protein activator 1 (RASA1) (11, 12). Subsequently, the protein product of the gene mutated in the human disease neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) was identified to contain a region of homology to RASA1 and to have RasGAP activity (13–17). In addition to a GAP domain, RASA1 contains Src homology 2 (SH2) and SH3 domains, which recognize phosphotyrosine- and proline-rich sequences in proteins, respectively, as well as pleckstrinhomology (PH) and protein kinase C2 homology domains that bind membrane phospholipids (Fig. 2A) (18). One important function of these four domains is thought to be in the targeting of RASA1 to membranes and, hence, Ras. For example, SH2 domains enable binding of RASA1 to phosphorylated receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) (Fig. 2B), such as the epidermal growth factor receptor, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, and insulin receptors, which promotes inactivation of Ras in the respective signaling pathways (19–24). Similarly, PH and C2 domains may also promote membrane targeting through direct binding to the lipid bilayer or indirect binding mediated through adaptor proteins, such as annexin A6 (25, 26). However, of the large number of RASA1 binding proteins that have been identified [reviewed in (27)], some may not have a role in targeting RASA1 to Ras but, instead, may function with RASA1 in Ras-independent mechanisms of signal transduction. One example of a Ras-independent function is the interaction between RASA1 and p190 RhoGAP, which acts as a GAP for the Ras superfamily protein Rho (28, 29).

Fig. 2.

(A) Domain organization of the RasGAP family members. (B) Domain-directed membrane localization of RasGAPs. Shown are examples of the different mechanisms by which RasGAPs can be targeted to membranes and Ras-GTP. RASA1 SH2 domains can bind phosphotyrosine residues located in intracellular domains of activated RTK. The RASA3 PH domain binds PIP2, which is present constitutively in membranes. The RASA2 and RASA3 PH domains can also recognize PIP3 generated in membranes in activated cells as a result of phosphorylation of PIP2 by PI3K. Both C2 domains of RASA4 and RASAL1 are able to recognize membrane phospholipids. NF1 can be targeted to membranes through an undefi ned interaction with the SPRED1 protein that binds to membrane lipids through its SPR domain.

NF1 contains just one recognized modular binding domain, a SEC14-PH domain, in addition to a GAP domain (Fig. 2A) (30). The SEC14-PH domain of NF1 binds glycerophospholipids and, thus, could potentially target NF1 to membranes (31). Sprouty-related protein with an Ena and vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) homology (EVH) domain 1 (SPRED1) recruits NF1 to membranes and is required for NF1 to inactivate Ras in cell lines (32). The EVH domain of SPRED1 engages NF1 and an N-terminal Sprouty (SPR) domain allows membrane localization of the SPRED1-NF1 complex, most likely through interaction with phospholipids and caveolin 1 (32–34) (Fig. 2B). Which NF1 protein region is recognized by the EVH domain and whether or not the SEC14-PH domain of NF1 cooperates with SPRED1 in membrane targeting is not known.

The GAP1m family

The GAP1 family of mammalian RasGAPs was identified on the basis of homology to the Drosophila RasGAP, Gap1 (35, 36). This family comprises mammalian GAP (GAP1m or RASA2); inositol 1,3,4,5 tetrakisphosphate–binding GAP1 (GAP1IP4BP or RASA3); calcium-promoted Ras inactivator (CAPRI or RASA4); and RASA like-1 (RASAL1) (37–40). Each member of the GAP1 family contains two N-terminal C2 domains followed by a GAP domain and a PH domain with a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) motif (Fig. 2A). The PH domains of RASA2 and RASA3 bind to phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3), and the PH domain of RASA3 additionally recognizes phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2), phospholipids that are enriched at the plasma membrane (41–44) (Fig. 2B). This difference in PIP2 or PIP3 recognition means that RASA2 is recruited to membranes upon activation of PI3K, which converts PIP2 to PIP3, whereas RASA3 is found constitutively at membranes. The C2 domains of RASA4 and RASAL1 (Fig. 2B) mediate membrane association in response to increases in intracellular calcium concentration (39, 45, 46). RASA4 associates stably with membranes in response to calcium. By contrast, RASAL1 senses oscillations in intracellular calcium and shuttles between the membrane and cytoplasm.

RASA3, RASA4, and RASAL1 also show GAP activity toward the Ras-related small GTPase, Rap (47). RapGAP activity of these GAP1 family members is also dependent on an arginine finger in its GAP domain, even though Rap lacks the equivalent of Ras Gln61 (48, 49). Furthermore, isolated soluble RASA4 and RASAL1 are devoid of RasGAP activity that requires conformational changes in the GAP domain triggered by membrane localization. For RASAL1, calcium-dependent C2 domain interaction with membrane phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylinositol lipids is the critical event that triggers its RasGAP activity (50).

The SynGAP family

Synaptic GAP (SynGAP) was the first described member of another family of RasGAPs that contain a PH domain and a single C2 domain both N-terminal to the GAP domain (51, 52) (Fig. 2A). Ligands of the SynGAP PH and C2 domains remain to be defined. SynGAP, similar to RASA3, RASA4, and RASAL1, has RapGAP as well as RasGAP activity (53). RapGAP activity is dependent on the SynGAP C2 domain. In neurons, SynGAP is concentrated within the postsynaptic density (PSD) structure located at the cytoplasmic side of glutamatergic excitatory synapses. Incorporation into the PSD is mediated through physical interaction with PSD proteins PSD-95 and SAP102. Both proteins contain PDZ (PSD95-DLG-ZO1) domains that bind to a C-terminal peptide sequence of SynGAP (51).

Other members of the SynGAP family include disabled-2 (DAB2)–interacting protein [DAB2ip, also known as apoptosis signal–regulating kinase 1 (ASK1)–h-interacting protein (AIP1)], nematode-like Ras-GAP (nGAP or RASAL2), and RASAL3 (54–58). The DAB2ip PH and C2 domains promote constitutive plasma membrane association, and the C2 domain additionally mediates interaction with ASK1 (55, 59). In blood vessel endothelial cells (ECs), DAB2ip interacts constitutively with tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1 (TNFR1) and, in response to vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A), with VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) (59, 60). Interaction with these receptors would allow additional means of membrane recruitment, although no evidence currently exists to indicate that the purpose of binding is to regulate the activation of Ras in the respective receptor-induced signaling pathways. Association of RASAL2 with membranes at the leading edge of migrating astrocytes is mediated through physical interaction with epithelial cell transforming factor 2 (ECT2), which acts as a RhoGEF (61). The regions of RASAL2 that bind ECT2 and the effect of the interaction upon Ras are unknown.

Tissue Distribution of RasGAPs

Several of the RasGAPs show broad patterns of tissue distribution, whereas others are found in a restricted number of tissues. Ubiquitously distributed RasGAPs include RASA1, NF1, RASA2, DAB2ip, and RASAL2 (37, 54, 56, 62–66). Of the other Ras-GAPs, RASA3 is most abundant in the brain and spleen, RASA4 is found mostly in the spleen and the lymph nodes, RASAL1 is largely confined to the thyroid and the adrenal glands, and SynGAP is present specifically in neurons (36, 38, 40, 51, 52, 65–67). The tissue distribution of RASAL3 has not been reported, but information from public databases indicates that this RasGAP may be confined to the hematopoietic system. In any one cell type, therefore, multiple RasGAPs are likely present. Despite this, loss of expression or genetic alteration of a single RasGAP-encoding gene is often sufficient to perturb tissue homeostasis in mouse and human.

Physiological Roles of RASA1

Genetically RASA1-deficient mice die at day 10 of embryonic development (E10) (Table 1). In yolk sacs, ECs fail to organize into a honeycombed network, and in the embryo, blood vessel growth abnormalities and ruptures are observed (68). Therefore, RASA1 is essential for normal development of the blood vascular system. Specific deletion of RASA1 within vascular ECs, achieved with the use of a conditional RASA1-deficient mouse strain, results in the same phenotype, which shows that RASA1 performs an EC-intrinsic role as a regulator of blood vessel growth (64, 69). Curiously, de novo deletion of RASA1 in adult mice does not cause spontaneous blood vessel abnormalities. Instead, massive overgrowth of the lymphatic vascular system results, associated with lymphatic vessel leakage and death from chylothorax (leakage of lymph fluid into the pleural cavity) (69). Specific deletion of RASA1 within lymphatic vessel ECs showed that RASA1 performs an EC-intrinsic role as a regulator of lymphatic vessel growth and function (69). In lymphatic vessel ECs, RASA1 is necessary to suppress Ras activation induced by VEGFR3 in response to its ligand, VEGF-C. It is postulated that, in the absence of RASA1, VEGF-C, which is present at low concentrations in the extravascular space in resting (unstimulated) animals, binds VEGFR3 and triggers chronic unopposed activation of the Ras pathway, which leads to lymphatic vessel hyperplasia and dysfunction.

Table 1.

Phenotypes of RasGAP mutant mice. Mutations are all knockouts except RASA3 G125V, which is a spontaneous mutant. Abbreviations: BV, blood vessel; LV, lymphatic vessel; E, embryonic day; P, postnatal day.

| RasGAP | Mutation | Phenotype | Receptors | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RASA1 | Nonconditional | Abnormal BV development E10.5 lethal | Unknown | (68) |

| EC-specific | Abnormal BV development E10.5 lethal | Unknown | (69) | |

| T cell–specific | Abnormal T cell development and survival | TCR, IL-7R | (72, 73) | |

| Broad inducible | LV hyperplasia and chylothorax | VEGFR3 | (69) | |

| Increased BV angiogenesis | FGFR | (71) | ||

| LV-specific inducible | LV hyperplasia and chylothorax | VEGFR3 | (69) | |

| NF1 | Nonconditional | Cardiovascular and neuronal abnormalities E13.5 lethal | Unknown | (87, 88) |

| EC-specific | Cardiovascular abnormalities E13.5 lethal | Unknown | (89) | |

| Schwann cell–specific | Plexiform neurofibromas | Unknown | (92, 93) | |

| Broad inducible | Myeloproliferative disorder | GM-CSF, IL-3, SCF | (95–97, 99) | |

| Benign cutaneous lymphomas | Unknown | (94) | ||

| RASA3 | Nonconditional-GAP-deficient | BV leakage E13.5 lethal | Unknown | (108) |

| G125V | Severe combined anemia and thrombocytopenia (Scat) P30 lethal | Unknown | (109) | |

| RASA4 | Nonconditional | Impaired macrophage phagocytosis | FcR | (67) |

| SynGAP | Nonconditional | Neuronal apoptosis P1-7 lethal | NMDA-type glutamate receptor | (118–120) |

| Brain-specific | Neuronal apoptosis P1–7 lethal | NMDA-type glutamate receptor | (121) | |

| DAB2ip | Nonconditional | Increased inflammatory BV angiogenesis | VEGFR2 | (60) |

| Increased aortic graft arteriosclerosis | IFN-γR | (141) |

The molecular basis for abnormal blood vessel development in RASA1-deficient embryonic mice is unknown. However, relevant to this phenotype is the finding that RASA1 is necessary for directed cell movement in vitro (28). Therefore, impaired directed movement of ECs could cause blood vessel abnormalities, because they fail to position themselves correctly during embryonic development. This role for RASA1 in directed movement is mediated through its interaction with p190 RhoGAP and is apparently independent of its ability to regulate Ras (28, 29). The notion that RASA1 performs a Ras-independent function specifically in blood vessel development is consistent with the finding that transgenic overexpression of Ras in ECs has no influence on the blood vascular system but induces lymphatic vascular abnormalities similar to those reported in induced RASA1-deficient mice (70).

Although RASA1 does not regulate blood vessel growth in the steady state in adults, clear evidence has emerged of its function as an inhibitor of pathological angiogenesis (71) (Tables 1 and 2). Blood vessel growth in response to proangiogenic growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF), is augmented in induced RASA1 conditional-knockout mice. Moreover, blood vessel ECs from human tumors and hemangiomas, but not normal vessels, express large amounts of microRNA-132 (miR-132) that causes degradation of RASA1 mRNA. The importance of miR-132–induced loss of RASA1 in tumor angiogenesis is illustrated by the finding that antagonism of miR-132 inhibits angiogenesis and reduces tumor burden in a mouse model of human breast carcinoma.

Table 2.

RasGAPs and human disease.

| RasGAP | Alteration | Disease | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RASA1 | Germline-inactivating mutation | CM-AVM | Autosomal dominant | (74, 75) |

| MicroRNA-mediated loss of RASA1 RNA | Pathological angiogenesis | Involved in angiogenic switch | (71) | |

| NF1 | Germline-inactivating mutation | Neurofibromatosis | Autosomal dominant Evidence of somatic second hit mutation | (77–80, 147) |

| RASA4 | Reduced protein abundance | Breast cancer | Knockdown in human mammary epithelial cells promotes transformation | (112) |

| RASAL1 | Reduced expression or protein abundance | Multiple cancers | Knockdown in human fibroblasts promotes transformation Reduced RASAL1 observed in multiple cancer types |

(113–116) |

| Kidney fibrosis | Knockdown in human fibroblasts promotes fibrosis Reduced RASAL1 observed in fibroblasts from fibrotic kidneys |

(117) | ||

| SynGAP | Germline-inactivating mutation | Nonsyndromic mental retardation | de novo truncation mutations | (128) |

| DAB2ip | Reduced expression | Prostate, lung, breast, and gastrointestinal tumors | Functions as negative regulator of tumor growth and metastasis Reduced DAB2ip observed in primary cancers |

(54, 58, 132–135, 137) |

| SNP (rs1571801) |

Aggressive prostate cancer | Genome-wide association studies | (138) | |

| SNP (rs7025486) |

Abdominal aortic aneurysm Early onset myocardial infarction Peripheral arterial disease Pulmonary embolism |

Genome-wide association study | (142) |

The influence of RASA1 loss in mice is mostly restricted to ECs. In nonconditionally RASA1-deficient embryos, increased neuronal apoptosis is also observed, although it is unclear if this is secondary to abnormal vascular development (68). RASA1 also inhibits Ras during positive selection of T cells in the thymus and promotes naïve T cell survival in the peripheral immune system (72). However, RASA1 plays a relatively minor role in T cell survival, and its function in positive selection is revealed only in T cell receptor transgenic mice or in competitive bone marrow transfers (72, 73). In relation to cancer, mice in which RASA1 deficiency is induced in adults show no increased susceptibility to tumor development during their life span (64, 69).

RASA1 is a critical regulator of blood vessel development in humans. Germline-inactivating mutations of the RASA1 gene cause the blood vascular disorder: capillary malformation–arteriovenous malformation (CM-AVM) (74, 75) (Table 2). The defining characteristic of CM-AVM is the presence of small multifocal cutaneous CMs. In addition, one-third of patients develop areteriovenous fistulas, Parkes-Weber syndrome, and life-threatening AVM in which there is hypertrophy of an affected limb. The disease is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, and in affected families 95% of individuals with a mutated RASA1 allele develop CM-AVM, which attests to the high penetrance of the mutations. A random somatic second-hit mutation of the intact RASA1 allele during development is considered responsible for manifestation of disease, which would be consistent with the focal nature of lesions. Lymphatic vessel abnormalities in the form of lymphedema and chylothorax have also been observed in some CM-AVM patients, which indicates that RASA1 also promotes proper maintenance and function of lymphatic vasculature in humans as it does in mice (75, 76).

Physiological Roles of NF1

Germline mutations of the NF1 gene are the cause of the autosomal dominant disease neurofibromatosis, one of the most common human genetic disorders (77–81). Neurofibromatosis is characterized by the development of benign cutaneous or plexiform neurofibromas that are composed of multiple cell types normally found in peripheral nerves. In some cases, plexiform neurofibromas develop into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Neurofibromatosis patients show increased susceptibility to a number of other neoplasms, such as gliomas, pheochromocytomas, and juvenile chronic myelogenous leukemia (JCML). Other noncancerous manifestations of neurofibromatosis include abnormal skin pigmentation, skeletal malformations, and learning disabilities. Inherited NF1 mutations associated with neurofibromatosis are inactivating mutations, and in samples from both tumors and noncancerous lesions, second-hit mutations of the intact NF1 allele have been identified (82–86). Together, the findings suggest NF1 is a tumor suppressor and a regulator of tissue homeostasis in humans.

Mouse genetic studies have provided additional insight into the mechanisms by which NF1 regulates cell function. Genetically NF1-deficient mice develop cardiovascular abnormalities and hyperplasia of sympathetic ganglia and die in utero at E13.5 (87, 88). In mice, conditional deletion of NF1 in the ECs results in the same cardiovascular phenotype and death, which reveals an EC-intrinsic function for NF1 in cardiovascular development (89). Expression of the isolated GAP domain of NF1 in NF1-deficient mice rescues the cardiovascular phenotype, but hyperplasia of neural crest–derived tissues is still observed, and mice die shortly after birth (90). One interpretation of these findings is that NF1 performs functions in neural crest–derived tissue that are unrelated to its ability to inactivate Ras. However, in this case, the isolated GAP domain lacks the SEC14-PH domain and other regions that may be necessary for membrane targeting and juxtaposition to Ras. Furthermore, the notion that the loss of a Ras-independent NF1 function in neural crest–derived cells is responsible for abnormal neurological development in mice is inconsistent with the finding that these abnormalities can be reversed by inhibition of Ras signaling (91).

Specific biallelic deletion of NF1 in Schwann cells in mice results in the development of plexiform neurofibromas but only in an NF1 heterozygous-null background (92). The NF1 heterozygous-null, non–Schwann cell type that is necessary for tumor development is the bone marrow–derived mast cell, which is abundant in plexiform neurofibromas (93). NF1 heterozygous-null mast cells show increased proliferation and motility in response to the c-kit RTK ligand, stem cell factor (SCF), which is produced in large quantities by NF1-deficient Schwann cells. Resulting mast cell infiltration into peripheral nerves promotes a tumor-permissive environment through production of mitogens and angiogenic growth factors (91). Benign cutaneous neurofibromas are not observed in mice with Schwann cell–specific NF1 deletion, which indicates a different cell of origin for these lesions. Indeed, deletion of NF1 in skin-derived neural progenitors transplanted into naïve recipients induces cutaneous neurofibromas, which indicates that biallelic loss of NF1 in skin-derived neural progenitors is responsible for the development of these benign lesions (94).

Constitutive hematopoietic-specific deletion of NF1, transfer of NF1-deficient hematopoietic cells into wild-type recipient mice, or induced global deletion of NF1 in adult mice all result in the development of myeloid proliferative disease that parallels the increased susceptibility to JCML observed in neurofibromatosis patients (95–98). NF1-deficient hematopoietic cells and leukemic cells from neurofibromatosis patients with JCML show increased Ras activation and cell growth in response to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (95, 96). In addition, NF1-deficient hematopoietic cells show increased sensitivity to interleukin 3 (IL-3) and SCF (99). Therefore, uncontrolled Ras activation downstream of multiple cytokine receptors may explain susceptibility to myeloid proliferative disorders in NF1-deficient mice and humans.

Legius syndrome is a mild form of neurofibromatosis that is associated with skin pigmentation abnormalities, macrocephaly, facial dysmorphism, and increased susceptibility to some types of tumors, although not specifically neurofibromas (100–105). It is caused by germline mutations of the SPRED1 gene that act in a dominant fashion. The majority of SPRED1 mutations are nonsense mutations that lack the SPR domain, which results in the loss of membrane localization of NF1 in cultured cells. The phenotypic similarity between Legius syndrome and neurofibromatosis suggests that targeting of NF1 to membranes and, therefore, its targeting to Ras is mediated by SPRED1 in some cell types. In other cell types, such as Schwann cells and skin-derived neural progenitors, NF1 must use alternative mechanisms to localize to the membranes. It is possible that NF1 binds membranes in these cell types through recognition of SPRED2 or SPRED3, proteins that are homologous to SPRED1 (106, 107). In cell lines, SPRED2 and SPRED3 mediate the recruitment of NF1 to membranes in the absence of SPRED1 (32).

Physiological Roles of the GAP1m Family

RASA3

Mice with a mutant form of RASA3 that lacks catalytic activity, but in which all other domains are intact, die in utero at E12.5 to E13.5 from massive hemorrhaging (108), probably resulting from the underdeveloped nature of adherens junctions between capillary ECs in these mice. Therefore, similar to RASA1 and NF1, RASA3 has a nonredundant function in the regulation of blood vessel development in mice. Furthermore, this function of RASA3 is relevant to its ability to inactivate Ras (or, theoretically, Rap). A rare, spontaneous G125V point mutation between the two C2 domains in the RASA3 gene causes the autosomal recessive disorder severe combined anemia and thrombocytopenia (SCAT) in BALB/cBy mice (109, 110). Anemia and thrombocytopenia in this model are a consequence of blocked erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis and are characterized by alternating cycles of crisis and remission with high mortality (109). The block in erythropoiesis appears to be at a terminal stage in which reticulocytes give rise to erythrocytes. In wild-type reticulocytes, RASA3 is membrane-localized. However, in Scat reticulocytes, RASA3 is cytosolic. Failure to target RASA3 to Ras is consistent with both the increased amount of Ras-GTP found in Scat erythrocytes and the Scat phenotype, because excessive Ras activation is known to block erythropoiesis in mice (111). Why vascular function is not also impaired in Scat mice is unclear. Potentially, this could be explained by the use of an alternative mechanism to target RASA3 to the membrane in blood vessel ECs, or, by analogy to NF1, by the lack of a requirement for modular binding domains to enable RASA3 to inactivate Ras in this specific cell type.

RASA4 and RASAL1

RASA4-deficient mice are viable but show decreased clearance of lung bacterial infections attributable to impaired antibody Fc receptor (FcR)–mediated phagocytosis in macrophages (67). RASA4 is required for FcR-induced activation of the Rho-related small GTPases, Cdc42 and Rac1, which are necessary for phagocytic cup formation. How RASA4 participates in Cdc42 and Rac1 activation is not understood. RASA4 does not act as a GEF for Cdc42 and Rac1, although it does interact physically with both molecules through its GAP domain (67). RASA4 also suppresses Ras activation during FcR signal transduction (67), albeit the significance of this inhibition with respect to impaired phagocytosis in RASA4-deficient mice is unclear.

In an RNA interference–based screen of human mammary epithelial cells, RASA4 was identified as one of several targets which promoted cell transformation when depleted, which implicates RASA4 as a tumor suppressor (112). However, increased susceptibility of RASA4-deficient mice to tumor formation has not been reported. A similar genetic screen performed in fibroblasts identified the paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 1 (PITX1) as a tumor suppressor; loss of PITX1 promotes cell transformation in a Ras-dependent manner (113). RASAL1 was identified as a direct transcriptional target of PITX1, and knockdown of RASAL1 also resulted in Ras-dependent cell transformation. RASAL1 abundance is frequently decreased in various tumor cell types, which indicates that RASAL1 may function as a tumor suppressor. In cancer cell lines, RASAL1 was silenced through promoter CpG methylation rather than through PITX1 deficiency (114–116). RASAL1 deficiency caused by hypermethylation of RASAL1 in fibroblasts may be the mechanism underlying uncontrolled fibroblast activation in kidney fibrosis in mice and humans, particularly because knockdown of RASAL1 in normal fibroblasts in vitro results in a fibrotic phenotype, as evidenced by increased proliferation and expression of fibrotic markers (117).

Physiological Roles of the SynGAP Family

SynGAP

Genetically SynGAP-deficient mice die within the first week of postnatal life (118–120). Conditional SynGAP-deficient mice, in which brain SynGAP abundance is reduced to 20% of that observed in wild-type mice, also results in death; however, when brain SynGAP is reduced only to 40% of wild-type abundance, mice survive (121). SynGAP abundance correlates inversely with the extent of neuronal apoptosis, which explains the mortality observed in severely SynGAP-deficient mice (121). Heterozygous SynGAP-deficient mice, although viable, exhibit abnormalities in cognition and behavior, functions that are controlled by the hippocampus (122–124). These mice show an increase in the number of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)–type glutamate receptor complexes in synapses and defects in hippocampal long-term potentiation that could provide a basis for the cognitive and behavioral phenotype (118, 119). Homozygous SynGAP-deficient neurons in vitro show increased Ras activation and decreased activation of the p38 MAPK in response to synaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)–type glutamate receptor activation, both of which may lie upstream of altered AMPA-type receptor clustering and response (125, 126). SynGAP-deficient neurons also show increased activation of Rac, which causes increased neuronal spine formation in vitro (120, 127). Notably, this spine formation phenotype can be corrected by expression of wild-type SynGAP but not by SynGAP mutants lacking GAP activity or the PSD-95–binding region (120), which indicates that functional SynGAP and its interaction with PSD-95 affect the regulation of neuronal morphology. As a corollary to these findings in mice, inherited de novo truncation mutations in the SYNGAP gene cause some cases of nonsyndromic mental retardation in humans (128).

DAB2ip

Studies performed with blood vessel ECs in vitro indicate an important function for DAB2ip in TNFR1 signaling (55, 59, 129, 130). In unstimulated blood vessel ECs, DAB2ip associates with TNFR1 in a closed conformation formed by binding between the N-terminal C2 domain and a C-terminal proline-rich region in DAB2ip. In response to TNF binding to TNFR1, DAB2ip is released from TNFR1 and forms an open conformation subsequent to phosphorylation by the receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1) kinase, which binds the DAB2ip GAP domain. The C2 domain of DAB2ip then binds ASK1, which promotes ASK1 dephosphorylation and activation by the protein phosphatase PP2A, which also associates with the DAB2ip GAP domain. Simultaneously, the open conformation of DAB2ip associates with TNFR-associated factor 2 (TRAF2), which results in inhibition of TNF-induced activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway. Through activation of ASK1 and inhibition of NF-κB, DAB2ip is thought to promote TNF-induced apoptosis in blood vessel ECs. Similarly, DAB2ip promotes endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced activation of ASK1 and apoptosis in both blood vessel ECs and fibroblasts (131).

Abundance of DAB2ip is commonly decreased in primary cells and cell lines derived from prostate, breast, lung, and gastrointestinal tumors (54, 58, 132–135). In each of these cell types, promoter methylation is one mechanism of gene suppression (132–135). Both histone methylation, mediated by the Polycomb repressive complex 2,3 protein Ezh2 (enhancer of Zeste homolog 2), and histone deacetylation have major roles in prostate cancer cells (132, 136, 137). Reexpression of DAB2ip in these cells restricts their growth in vitro, which indicates that loss of DAB2ip promotes transformation (54, 58). This is also consistent with the findings of two genome-wide association studies in humans, which show that a DAB2ip single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is significantly associated with genetic susceptibility to aggressive prostate cancer (138).

Mechanistically, loss of DAB2ip appears to promote both transformation and tumor metastasis (137). Short hairpin RNA-mediated knockdown of DAB2ip in human prostate epithelial cells results in metastatic prostate cancer, when injected into mice. Reexpression of a catalytically inactive form of DAB2ip containing a GAP domain point mutation does not suppress tumor growth in vivo but does inhibit metastasis. Conversely, reexpression of a catalytically active form of DAB2ip containing a point mutation in its C-terminal region, which abrogates its ability to inhibit NF-κB, inhibits tumor growth but not metastasis. Together, these findings indicate that DAB2ip inhibits tumor growth by suppressing Ras and inhibits metastasis by suppressing NF-κB. In addition, the ability of DAB2ip to suppress PI3K and the PKB pathway and to promote ASK activation in prostate epithelial cells likely contributes to its function as a tumor suppressor (139). Increased activation of NF-κB in DAB2ip-deficient prostate epithelial cells results in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), marked by increased mesenchymal marker abundance on prostate epithelial cells, which is associated with metastasis (137, 140), and that suggests that DAB2ip inhibits EMT and metastasis.

Although blood vessel development is normal in DAB2ip-deficient mice, inflammation-induced angiogenesis is increased and is attributed to augmented signaling through VEGFR2 in blood vessel ECs (60). However, as in the TNFR signaling pathway, the role of DAB2ip in VEGFR2 signaling appears unrelated to its ability to directly inhibit Ras activity. Instead, DAB2ip inhibits VEGFR2-mediated activation of PI3K and phospholipase C through binding to the receptor complex. Loss of DAB2ip in aortic grafts results in graft arteriosclerosis accompanied by intima expansion (141). In the absence of DAB2ip, vascular smooth muscle cells show increased migration and proliferation in response to the inflammatory cytokine, interferon gamma (IFN-γ), which is critical to neointima formation. DAB2ip normally inhibits IFN-γ signaling through direct binding to and inhibition of receptor-associated Janus-activated tyrosine kinase 2 (JAK2) (141). DAB2ip is also implicated as a regulator of the blood vascular system in humans. A genome-wide association study shows an association between a DAB2ip SNP and, separately, early onset myocardial infarction, peripheral arterial disease, pulmonary embolism, and abdominal aortic aneurysm (142).

RASAL2

Knockdown of RASAL2 in astrocytoma cells increases the activation of Rho and induces a mesenchymal-to-amoeboid transition associated with a change in tumor cell migratory properties (61). The change in Rho activation could indicate a function for RASAL2 as a RhoGAP in this cell type. Alternatively, through modulation of the GEF activity of ECT2, RASAL2 could affect Rho activation indirectly.

The Nonredundant Nature of RasGAPs in Tissue-Specific Homeostasis

Of the 10 members of the RasGAP family, loss of function of all but 2 is sufficient to confer phenotype at the cellular or organism level. For RASA2 and RASAL3, knockdown and knockout studies have yet to be reported. This apparent lack of functional redundancy between RasGAPs can be explained by the fact that different cell surface receptors appear to target one or a limited number of RasGAPs in order to terminate Ras signaling. At the molecular level, it seems likely that selectivity is dependent on receptor-generated signals that recruit specific RasGAPs to the membrane or receptor complex. Why only a limited number of RasGAPs are used by an individual receptor is unknown. It is possible that different receptors may activate distinct Ras family isoforms at different plasma membrane microdomains and endomembrane sites (143), and these isoforms, in turn, may be inhibited by distinct RasGAPs. For example, among the Ras isoforms, RASA1 shows increased activity toward R-Ras compared with H-Ras, and NF1 shows strongest activity toward K-Ras (144–146). In addition, a select few RasGAPs also have RapGAP activity. Thus, there may be a requirement for specialized RasGAPs with particular enzymatic specificities to selectively inhibit the activation of individual Ras family members or Rap at distinct sites within the cell. Furthermore, several RasGAPs also perform nonredundant Ras-independent functions in cellular signal transduction, which provides a further basis for RasGAP-specific loss-of-function phenotypes.

A remaining question concerns the basis for tissue-specific phenotypes in mice and humans when a RasGAP is knocked out in all tissues. In part, this may result from differing consequences of increased Ras activation in different cell types. For example, Ras overexpression in ECs does not affect blood vessel development but does lead to lymphatic vessel hyperplasia (70). Furthermore, the oncogenic potential of Ras varies among different cell lineages (9). Alternatively, there is the possibility of genuine functional redundancy between RasGAPs in certain cell types and tissues. Evidence of this redundancy exists in blood vessel development, where it is observed that nonconditional double RASA1- and NF1-deficient mice show more severe blood vessel abnormalities and die at an earlier time point in embryogenesis than mice that lack either single RasGAP (68). This suggests that RASA1 and NF1 have partially overlapping and redundant functions in the signaling pathway that regulates blood vessel development.

Conclusion

Continuing analyses of the physiological function of RasGAPs are revealing essential roles for individual family members as regulators of vascular, hematopoietic, immune, and neuronal systems. Different RTKs appear to use distinct RasGAP family members to inactivate Ras, which makes RasGAPs important tumor suppressors and critical regulators of tissue homeostasis in humans. In addition, several RasGAPs have distinct Ras-independent functions in cell signal transduction. Together, these functions exemplify the varied, yet nonredundant, roles of RasGAPs in mammalian physiology.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grant HL096498 and by American Heart Association grants 11POST7580023 and 12PRE8850000.

References and Notes

- 1.Wennerberg K, Rossman KL, Der CJ. The Ras superfamily at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:843–846. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bos JL, Rehmann H, Wittinghofer A. GEFs and GAPs: Critical elements in the control of small G proteins. Cell. 2007;129:865–877. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buday L, Downward J. Many faces of Ras activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1786:178–187. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang L, Karin M. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature. 2001;410:37–40. doi: 10.1038/35065000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donovan S, Shannon KM, Bollag G. GTPase activating proteins: Critical regulators of intracellular signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1602:23–45. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(01)00041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmadian MR, Kiel C, Stege P, Scheffzek K. Structural fingerprints of the Ras-GTPase activating proteins neurofibromin and p120GAP. J Mol Biol. 2003;329:699–710. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00514-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheffzek K, Ahmadian MR, Kabsch W, Wiesmüller L, Lautwein A, Schmitz F, Wittinghofer A. The Ras-RasGAP complex: Structural basis for GTPase activation and its loss in oncogenic Ras mutants. Science. 1997;277:333–338. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmadian MR, Hoffmann U, Goody RS, Wittinghofer A. Individual rate constants for the interaction of Ras proteins with GTPase-activating proteins determined by fluorescence spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4535–4541. doi: 10.1021/bi962556y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Grabocka E, Bar-Sagi D. RAS oncogenes: Weaving a tumorigenic web. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:761–774. doi: 10.1038/nrc3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prior IA, Lewis PD, Mattos C. A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2457–2467. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogel US, Dixon RA, Schaber MD, Diehl RE, Marshall MS, Scolnick EM, Sigal IS, Gibbs JB. Cloning of bovine GAP and its interaction with oncogenic ras p21. Nature. 1988;335:90–93. doi: 10.1038/335090a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trahey M, Wong G, Halenbeck R, Rubinfeld B, Martin G, Ladner M, Long C, Crosier W, Watt K, Koths K, et al. Molecular cloning of two types of GAP complementary DNA from human placenta. Science. 1988;242:1697–1700. doi: 10.1126/science.3201259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marchuk DA, Saulino AM, Tavakkol R, Swaroop M, Wallace MR, Andersen LB, Mitchell AL, Gutmann DH, Boguski M, Collins FS. cDNA cloning of the type 1 neurofibromatosis gene: Complete sequence of the NF1 gene product. Genomics. 1991;11:931–940. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballester R, Marchuk D, Boguski M, Saulino A, Letcher R, Wigler M, Collins F. The NF1 locus encodes a protein functionally related to mammalian GAP and yeast IRA proteins. Cell. 1990;63:851–859. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin GA, Viskoohil D, Bollag G, Mc-Cabe PC, Crosier WJ, Haubruck H, Conroy L, Clark R, O’Connell P, Cawthon RM, Innis MA, McCormick F. The GAP-related domain of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene product interacts with ras p21. Cell. 1990;63:843–849. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90150-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu GF, Lin B, Tanaka K, Dunn D, Wood D, Gesteland R, White R, Weiss R, Tamanoi F. The catalytic domain of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene product stimulates ras GTPase and complements ira mutants of S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1990;63:835–841. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu GF, O’Connell P, Viskochil D, Cawthon R, Robertson M, Culver M, Dunn D, Stevens J, Gesteland R, White R, Weiss R. The neurofibromatosis type 1 gene encodes a protein related to GAP. Cell. 1990;62:599–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuriyan J, Cowburn D. Modular peptide recognition domains in eukaryotic signaling. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1997;26:259–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.26.1.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agazie YM, Hayman MJ. Molecular mechanism for a role of SHP2 in epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7875–7886. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7875-7886.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper JA, Kashishian A. In vivo binding properties of SH2 domains from GTPase-activating protein and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1737–1745. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.3.1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekman S, Thuresson ER, Heldin CH, Rönnstrand L. Increased mitogenicity of an alpha-beta heterodimeric PDGF receptor complex correlates with lack of RasGAP binding. Oncogene. 1999;18:2481–2488. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fantl WJ, Escobedo JA, Martin GA, Turck CW, del Rosario M, McCormick F, Williams LT. Distinct phosphotyrosines on a growth factor receptor bind to specific molecules that mediate different signaling pathways. Cell. 1992;69:413–423. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90444-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kazlauskas A, Ellis C, Pawson T, Cooper JA. Binding of GAP to activated PDGF receptors. Science. 1990;247:1578–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.2157284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Margolis B, Li N, Koch A, Mohammadi M, Hurwitz DR, Zilberstein A, Ullrich A, Pawson T, Schlessinger J. The tyrosine phosphorylated carboxyterminus of the EGF receptor is a binding site for GAP and PLC-gamma. EMBO J. 1990;9:4375–4380. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07887.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grewal T, Evans R, Rentero C, Tebar F, Cubells L, de Diego I, Kirchhoff MF, Hughes WE, Heeren J, Rye KA, Rinninger F, Daly RJ, Pol A, Enrich C. Annexin A6 stimulates the membrane recruitment of p120GAP to modulate Ras and Raf-1 activity. Oncogene. 2005;24:5809–5820. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muga S Vilá de, Timpson P, Cubells L, Evans R, Hayes TE, Rentero C, Hegemann A, Reverter M, Leschner J, Pol A, Tebar F, Daly R, Enrich C, Grewal T. Annexin A6 inhibits Ras signalling in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:363–377. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pamonsinlapatham P, Hadj-Slimane R, Lepelletier Y, Allain B, Toccafondi M, Garbay C, Raynaud F. p120-Ras GTPase activating protein (Ras-GAP): A multi-interacting protein in downstream signaling. Biochimie. 2009;91:320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulkarni SV, Gish G, van der Geer P, Henkemeyer M, Pawson T. Role of p120 Ras-GAP in directed cell movement. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:457–470. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.2.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Geer P, Henkemeyer M, Jacks T, Pawson T. Aberrant Ras regulation and reduced p190 tyrosine phosphorylation in cells lacking p120-Gap. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1840–1847. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Angelo I, Welti S, Bonneau F, Scheffzek K. A novel bipartite phospholipid-binding module in the neurofibromatosis type 1 protein. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:174–179. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Welti S, Fraterman S, D’Angelo I, Wilm M, Scheffzek K. The sec14 homology module of neurofibromin binds cellular glycerophospholipids: Mass spectrometry and structure of a lipid complex. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:551–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stowe IB, Mercado EL, Stowe TR, Bell EL, Oses-Prieto JA, Hernández H, Burlingame AL, McCormick F. A shared molecular mechanism underlies the human rasopathies Legius syndrome and Neurofibromatosis-1. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1421–1426. doi: 10.1101/gad.190876.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim J, Yusoff P, Wong ES, Chandramouli S, Lao DH, Fong CW, Guy GR. The cysteine-rich sprouty translocation domain targets mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitory proteins to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in plasma membranes. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7953–7966. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7953-7966.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nonami A, Kato R, Taniguchi K, Yoshiga D, Taketomi T, Fukuyama S, Harada M, Sasaki A, Yoshimura A. Spred-1 negatively regulates interleukin-3-mediated ERK/mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase activation in hematopoietic cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52543–52551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405189200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yarwood S, Bouyoucef-Cherchalli D, Cullen PJ, Kupzig S. The GAP1 family of GTPase-activating proteins: Spatial and temporal regulators of small GTPase signalling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:846–850. doi: 10.1042/BST0340846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cullen PJ, Lockyer PJ. Integration of calcium and Ras signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:339–348. doi: 10.1038/nrm808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maekawa M, Li S, Iwamatsu A, Morishita T, Yokota K, Imai Y, Kohsaka S, Nakamura S, Hat-tori S. A novel mammalian Ras GTPase-activating protein which has phospholipid-binding and Btk homology regions. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6879–6885. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamamoto T, Matsui T, Nakafuku M, Iwamatsu A, Kaibuchi K. A novel GTPase-activating protein for R-Ras. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30557–30561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.51.30557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lockyer PJ, Kupzig S, Cullen PJ. CAPRI regulates Ca(2+)-dependent inactivation of the Ras-MAPK pathway. Curr Biol. 2001;11:981–986. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allen M, Chu S, Brill S, Stotler C, Buckler A. Restricted tissue expression pattern of a novel human rasGAP-related gene and its murine ortholog. Gene. 1998;218:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cozier GE, Lockyer PJ, Reynolds JS, Kupzig S, Bottomley JR, Millard TH, Banting G, Cullen PJ. GAP1IP4BP contains a novel group I pleckstrin homology domain that directs constitutive plasma membrane association. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28261–28268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cozier GE, Bouyoucef D, Cullen PJ. Engineering the phosphoinositide-binding profile of a class I pleckstrin homology domain. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39489–39496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307785200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lockyer PJ, Bottomley JR, Reynolds JS, McNulty TJ, Venkateswarlu K, Potter BV, Dempsey CE, Cullen PJ. Distinct subcellular localisations of the putative inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate receptors GAP1IP4BP and GAP1m result from the GAP1IP4BP PH domain directing plasma membrane targeting. Curr Biol. 1997;7:1007–1010. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00423-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lockyer PJ, Wennström S, Kupzig S, Venkateswarlu K, Downward J, Cullen PJ. Identification of the ras GTPase-activating protein GAP1(m) as a phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate-binding protein in vivo. Curr Biol. 1999;9:265–269. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walker SA, Kupzig S, Bouyoucef D, Davies LC, Tsuboi T, Bivona TG, Cozier GE, Lockyer PJ, Buckler A, Rutter GA, Allen MJ, Philips MR, Cullen PJ. Identification of a Ras GTPase-activating protein regulated by receptor-mediated Ca2+ oscillations. EMBO J. 2004;23:1749–1760. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Q, Walker SA, Gao D, Taylor JA, Dai YF, Arkell RS, Bootman MD, Roderick HL, Cullen PJ, Lockyer PJ. CAPRI and RASAL impose different modes of information processing on Ras due to contrasting temporal filtering of Ca2+ J Cell Biol. 2005;170:183–190. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kupzig S, Deaconescu D, Bouyoucef D, Walker SA, Liu Q, Polte CL, Daumke O, Ishizaki T, Lockyer PJ, Wittinghofer A, Cullen PJ. GAP1 family members constitute bifunctional Ras and Rap GTPase-activating proteins. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9891–9900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512802200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kupzig S, Bouyoucef-Cherchalli D, Yarwood S, Sessions R, Cullen PJ. The ability of GAP1IP4BP to function as a Rap1 GTPase-activating protein (GAP) requires its Ras GAP-related domain and an arginine finger rather than an asparagine thumb. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3929–3940. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00427-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sot B, Kötting C, Deaconescu D, Suveyzdis Y, Gerwert K, Wittinghofer A. Unravelling the mechanism of dual-specificity GAPs. EMBO J. 2010;29:1205–1214. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sot B, Behrmann E, Raunser S, Wittinghofer A. Ras GTPase activating (RasGAP) activity of the dual specificity GAP protein Rasal requires colocalization and C2 domain binding to lipid membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:111–116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201658110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim JH, Liao D, Lau LF, Huganir RL. SynGAP: A synaptic RasGAP that associates with the PSD-95/SAP90 protein family. Neuron. 1998;20:683–691. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen HJ, Rojas-Soto M, Oguni A, Kennedy MB. A synaptic Ras-GTPase activating protein (p135 SynGAP) inhibited by CaM kinase II. Neuron. 1998;20:895–904. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80471-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pena V, Hothorn M, Eberth A, Kaschau N, Parret A, Gremer L, Bonneau F, Ahmadian MR, Scheffzek K. The C2 domain of SynGAP is essential for stimulation of the Rap GTPase reaction. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:350–355. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Z, Tseng CP, Pong RC, Chen H, McConnell JD, Navone N, Hsieh JT. The mechanism of growth-inhibitory effect of DOC-2/DAB2 in prostate cancer. Characterization of a novel GTPase-activating protein associated with N-terminal domain of DOC-2/DAB2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12622–12631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang R, He X, Liu W, Lu M, Hsieh JT, Min W. AIP1 mediates TNF-alpha-induced ASK1 activation by facilitating dissociation of ASK1 from its inhibitor 14-3-3. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1933–1943. doi: 10.1172/JCI17790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Noto S, Maeda T, Hattori S, Inazawa J, Imamura M, Asaka M, Hatakeyama M. A novel human RasGAP-like gene that maps within the prostate cancer susceptibility locus at chromosome 1q25. FEBS Lett. 1998;441:127–131. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01530-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Díez D, Sánchez-Jiménez F, Ranea JA. Evolutionary expansion of the Ras switch regulatory module in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:5526–5537. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen H, Pong RC, Wang Z, Hsieh JT. Differential regulation of the human gene DAB2IP in normal and malignant prostatic epithelia: Cloning and characterization. Genomics. 2002;79:573–581. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang H, Zhang R, Luo Y, D’Alessio A, Pober JS, Min W. AIP1/DAB2IP, a novel member of the Ras-GAP family, transduces TRAF2-induced ASK1-JNK activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44955–44965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407617200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang H, He Y, Dai S, Xu Z, Luo Y, Wan T, Luo D, Jones D, Tang S, Chen H, Sessa WC, Min W. AIP1 functions as an endogenous inhibitor of VEGFR2-mediated signaling and inflammatory angiogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3904–3916. doi: 10.1172/JCI36168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weeks A, Okolowsky N, Golbourn B, Ivanchuk S, Smith C, Rutka JT. ECT2 and RASAL2 mediate mesenchymal-amoeboid transition in human astrocytoma cells. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:662–674. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bernards A. GAPs galore! A survey of putative Ras superfamily GTPase activating proteins in man and Drosophila. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1603:47–82. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(02)00082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dasgupta B, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis 1: Closing the GAP between mice and men. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:20–27. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lapinski PE, Bauler TJ, Brown EJ, Hughes ED, Saunders TL, King PD. Generation of mice with a conditional allele of the p120 Ras GTPase-activating protein. Genesis. 2007;45:762–767. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lockyer PJ, Vanlingen S, Reynolds JS, McNulty TJ, Irvine RF, Parys JB, Cullen PJ. Tissue-specific expression and endogenous subcellular distribution of the inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate-binding proteins GAP1(IP4BP) and GAP1(m) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;255:421–426. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McNulty TJ, Letcher AJ, Dawson AP, Ir-vine RF. Tissue distribution of GAP1IP4BP and GAP1m: Two inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate-binding proteins. Cell Signal. 2001;13:877–886. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang J, Guo J, Dzhagalov I, He YW. An essential function for the calcium-promoted Ras in-activator in Fcgamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:911–919. doi: 10.1038/ni1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Henkemeyer M, Rossi DJ, Holmyard DP, Puri MC, Mbamalu G, Harpal K, Shih TS, Jacks T, Pawson T. Vascular system defects and neuronal apoptosis in mice lacking ras GTPase-activating protein. Nature. 1995;377:695–701. doi: 10.1038/377695a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lapinski PE, Kwon S, Lubeck BA, Wilkin-son JE, Srinivasan RS, Sevick-Muraca E, King PD. RASA1 maintains the lymphatic vasculature in a quiescent functional state in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:733–747. doi: 10.1172/JCI46116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ichise T, Yoshida N, Ichise H. H-, N- and Kras cooperatively regulate lymphatic vessel growth by modulating VEGFR3 expression in lymphatic endothelial cells in mice. Development. 2010;137:1003–1013. doi: 10.1242/dev.043489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anand S, Majeti BK, Acevedo LM, Mur-phy EA, Mukthavaram R, Scheppke L, Huang M, Shields DJ, Lindquist JN, Lapinski PE, King PD, Weis SM, Cheresh DA. MicroRNA-132-mediated loss of p120RasGAP activates the endothelium to facilitate pathological angiogenesis. Nat Med. 2010;16:909–914. doi: 10.1038/nm.2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lapinski PE, Qiao Y, Chang CH, King PD. A role for p120 RasGAP in thymocyte positive selection and survival of naive T cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:151–163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Qiao Y, Zhu L, Sofi H, Lapinski PE, Horai R, Mueller K, Stritesky GL, He X, Teh HS, Wiest DL, Kappes DJ, King PD, Hogquist KA, Schwartzberg PL, Sant’Angelo DB, Chang CH. Development of promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger-expressing innate CD4 T cells requires stronger T-cell receptor signals than conventional CD4 T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:16264–16269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207528109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eerola I, Boon LM, Mulliken JB, Burrows PE, Dompmartin A, Watanabe S, Vanwijck R, Vikkula M. Capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation, a new clinical and genetic disorder caused by RASA1 mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:1240–1249. doi: 10.1086/379793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Revencu N, Boon LM, Mulliken JB, Enjolras O, Cordisco MR, Burrows PE, Clapuyt P, Hammer F, Dubois J, Baselga E, Brancati F, Carder R, Quintal JM, Dallapiccola B, Fischer G, Frieden IJ, Garzon M, Harper J, Johnson-Patel J, Labrèze C, Martorell L, Paltiel HJ, Pohl A, Prendiville J, Quere I, Siegel DH, Valente EM, Hagen A Van, Hest L Van, Vaux KK, Vicente A, Weibel L, Chitayat D, Vikkula M. Parkes Weber syndrome, vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation, and other fast-flow vascular anomalies are caused by RASA1 mutations. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:959–965. doi: 10.1002/humu.20746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.de Wijn RS, Oduber CE, Breugem CC, Alders M, Hennekam RC, van der Horst CM. Phenotypic variability in a family with capillary malformations caused by a mutation in the RASA1 gene. Eur J Med Genet. 2012;55:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cawthon RM, Weiss R, Xu G, Viskochil D, Culver M, Stevens J, Robertson M, Dunn D, Gesteland R, O’Connell P, White R. A major segment of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene: cDNA sequence, genomic structure, and point mutations. Cell. 1990;62:193–201. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90253-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McClatchey AI. Neurofibromatosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2007;2:191–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.2.010506.091940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Viskochil D, Buchberg AM, Xu G, Cawthon RM, Stevens J, Wolff RK, Culver M, Carey JC, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, White R, O’Connell P. Deletions and a translocation interrupt a cloned gene at the neurofibromatosis type 1 locus. Cell. 1990;62:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90252-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wallace MR, Marchuk D, Andersen L, Letcher R, Odeh H, Saulino A, Fountain J, Brereton A, Nicholson J, Mitchell A, et al. Type 1 neurofibromatosis gene: Identification of a large transcript disrupted in three NF1 patients. Science. 1990;249:181–186. doi: 10.1126/science.2134734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jouhilahti EM, Peltonen S, Heape AM, Peltonen J. The pathoetiology of neurofibromatosis 1. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1932–1939. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Legius E, Marchuk DA, Collins FS, Glover TW. Somatic deletion of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene in a neurofibrosarcoma supports a tumour suppressor gene hypothesis. Nat Genet. 1993;3:122–126. doi: 10.1038/ng0293-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maertens O, Brems H, Vandesompele J, Raedt T De, Heyns I, Rosenbaum T, Schepper S De, Paepe A De, Mortier G, Janssens S, Spele-man F, Legius E, Messiaen L. Comprehensive NF1 screening on cultured Schwann cells from neurofibromas. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:1030–1040. doi: 10.1002/humu.20389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.De Schepper S, Maertens O, Callens T, Naeyaert JM, Lambert J, Messiaen L. Somatic mutation analysis in NF1 café au lait spots reveals two NF1 hits in the melanocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1050–1053. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brems H, Park C, Maertens O, Pemov A, Messiaen L, Upadhyaya M, Claes K, Beert E, Peeters K, Mautner V, Sloan JL, Yao L, Lee CC, Sciot R, De Smet L, Legius E, Stewart DR. Glomus tumors in neurofibromatosis type 1: Genetic, functional, and clinical evidence of a novel association. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7393–7401. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Serra E, Rosenbaum T, Winner U, Aledo R, Ars E, Estivill X, Lenard HG, Lázaro C. Schwann cells harbor the somatic NF1 mutation in neurofibromas: Evidence of two different Schwann cell subpopulations. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:3055–3064. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.20.3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brannan CI, Perkins AS, Vogel KS, Rat-ner N, Nordlund ML, Reid SW, Buchberg AM, Jenkins NA, Parada LF, Copeland NG. Targeted disruption of the neurofibromatosis type-1 gene leads to developmental abnormalities in heart and various neural crest-derived tissues. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1019–1029. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jacks T, Shih TS, Schmitt EM, Bronson RT, Bernards A, Weinberg RA. Tumour predisposition in mice heterozygous for a targeted mutation in Nf1. Nat Genet. 1994;7:353–361. doi: 10.1038/ng0794-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gitler AD, Zhu Y, Ismat FA, Lu MM, Yamauchi Y, Parada LF, Epstein JA. Nf1 has an essential role in endothelial cells. Nat Genet. 2003;33:75–79. doi: 10.1038/ng1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ismat FA, Xu J, Lu MM, Epstein JA. The neurofibromin GAP-related domain rescues endothelial but not neural crest development in Nf1−/− mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2378–2384. doi: 10.1172/JCI28341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Le LQ, Parada LF. Tumor microenvironment and neurofibromatosis type I: Connecting the GAPs. Oncogene. 2007;26:4609–4616. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhu Y, Ghosh P, Charnay P, Burns DK, Parada LF. Neurofibromas in NF1: Schwann cell origin and role of tumor environment. Science. 2002;296:920–922. doi: 10.1126/science.1068452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yang FC, Ingram DA, Chen S, Zhu Y, Yuan J, Li X, Yang X, Knowles S, Horn W, Li Y, Zhang S, Yang Y, Vakili ST, Yu M, Burns D, Robertson K, Hutchins G, Parada LF, Clapp DW. Nf1-dependent tumors require a microenvironment containing Nf1+/−- and c-kit-dependent bone marrow. Cell. 2008;135:437–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Le LQ, Shipman T, Burns DK, Parada LF. Cell of origin and microenvironment contribution for NF1-associated dermal neurofibromas. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:453–463. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bollag G, Clapp DW, Shih S, Adler F, Zhang YY, Thompson P, Lange BJ, Freedman MH, McCormick F, Jacks T, Shannon K. Loss of NF1 results in activation of the Ras signaling pathway and leads to aberrant growth in haematopoietic cells. Nat Genet. 1996;12:144–148. doi: 10.1038/ng0296-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Largaespada DA, Brannan CI, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. Nf1 deficiency causes Ras-mediated granulocyte/macrophage colony stimulating factor hypersensitivity and chronic myeloid leukaemia. Nat Genet. 1996;12:137–143. doi: 10.1038/ng0296-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Le DT, Kong N, Zhu Y, Lauchle JO, Aiyigari A, Braun BS, Wang E, Kogan SC, Le Beau MM, Parada L, Shannon KM. Somatic inactivation of Nf1 in hematopoietic cells results in a progressive myeloproliferative disorder. Blood. 2004;103:4243–4250. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gitler AD, Kong Y, Choi JK, Zhu Y, Pear WS, Epstein JA. Tie2-Cre-induced inactivation of a conditional mutant Nf1 allele in mouse results in a myeloproliferative disorder that models juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:581–584. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000113462.98851.2E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang YY, Vik TA, Ryder JW, Srour EF, Jacks T, Shannon K, Clapp DW. Nf1 regulates hematopoietic progenitor cell growth and ras signaling in response to multiple cytokines. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1893–1902. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.11.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Spyk S Laycock-van, Jim HP, Thomas L, Spurlock G, Fares L, Palmer-Smith S, Kini U, Saggar A, Patton M, Mautner V, Pilz DT, Upadhyaya M. Identification of five novel SPRED1 germ-line mutations in Legius syndrome. Clin Genet. 2011;80:93–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Denayer E, Chmara M, Brems H, Kievit AM, van Bever Y, Van den Ouweland AM, Van Minkelen R, de Goede-Bolder A, Oostenbrink R, Lakeman P, Beert E, Ishizaki T, Mori T, Keymolen K, Van den Ende J, Mangold E, Peltonen S, Brice G, Rankin J, Van Spaendonck-Zwarts KY, Yoshimura A, Legius E. Legius syndrome in fourteen families. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:E1985–E1998. doi: 10.1002/humu.21404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Spurlock G, Bennett E, Chuzhanova N, Thomas N, Jim HP, Side L, Davies S, Haan E, Kerr B, Huson SM, Upadhyaya M. SPRED1 mutations (Legius syndrome): Another clinically useful genotype for dissecting the neurofibromatosis type 1 phenotype. J Med Genet. 2009;46:431–437. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.065474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Brems H, Chmara M, Sahbatou M, Denayer E, Taniguchi K, Kato R, Somers R, Messiaen L, De Schepper S, Fryns JP, Cools J, Marynen P, Thomas G, Yoshimura A, Legius E. Germline loss-of-function mutations in SPRED1 cause a neurofibromatosis 1-like phenotype. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1120–1126. doi: 10.1038/ng2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pasmant E, Sabbagh A, Hanna N, Masliah-Planchon J, Jolly E, Goussard P, Ballerini P, Cartault F, Barbarot S, Landman-Parker J, Soufir N, Parfait B, Vidaud M, Wolkenstein P, Vi-daud D, France RN. SPRED1 germline mutations caused a neurofibromatosis type 1 overlapping phenotype. J Med Genet. 2009;46:425–430. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.065243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Messiaen L, Yao S, Brems H, Callens T, Sathienkijkanchai A, Denayer E, Spencer E, Arn P, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Bay C, Bobele G, Cohen BH, Escobar L, Eunpu D, Grebe T, Green-stein R, Hachen R, Irons M, Kronn D, Lemire E, Leppig K, Lim C, McDonald M, Narayanan V, Pearn A, Pedersen R, Powell B, Shapiro LR, Skidmore D, Tegay D, Thiese H, Zackai EH, Vijzelaar R, Taniguchi K, Ayada T, Okamoto F, Yoshimura A, Parret A, Korf B, Legius E. Clinical and mutational spectrum of neurofibromatosis type 1-like syndrome. J Am Med Assoc. 2009;302:2111–2118. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kato R, Nonami A, Taketomi T, Wakioka T, Kuroiwa A, Matsuda Y, Yoshimura A. Molecular cloning of mammalian Spred-3 which suppresses tyrosine kinase-mediated Erk activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;302:767–772. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.King JA, Corcoran NM, D’Abaco GM, Straffon AF, Smith CT, Poon CL, Buchert M, i S, Hall NE, Lock P, Hovens CM. Eve-3: A liver enriched suppressor of Ras/MAPK signaling. J Hepatol. 2006;44:758–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Iwashita S, Kobayashi M, Kubo Y, Hinohara Y, Sezaki M, Nakamura K, Suzuki-Migishima R, Yokoyama M, Sato S, Fukuda M, Ohba M, Kato C, Adachi E, Song SY. Versatile roles of R-Ras GAP in neurite formation of PC12 cells and embryonic vascular development. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3413–3417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600293200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Blanc L, Ciciotte SL, Gwynn B, Hildick-Smith GJ, Pierce EL, Soltis KA, Cooney JD, Paw BH, Peters LL. Critical function for the Ras-GTPase activating protein RASA3 in vertebrate erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12099–12104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204948109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Peters LL, McFarland-Starr EC, Wood BG, Barker JE. Heritable severe combined anemia and thrombocytopenia in the mouse: Description of the disease and successful therapy. Blood. 1990;76:745–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhang J, Lodish HF. Endogenous K-ras signaling in erythroid differentiation. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1970–1973. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.16.4577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Westbrook TF, Martin ES, Schlabach MR, Leng Y, Liang AC, Feng B, Zhao JJ, Roberts TM, Mandel G, Hannon GJ, Depinho RA, Chin L, Elledge SJ. A genetic screen for candidate tumor suppressors identifies REST. Cell. 2005;121:837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kolfschoten IG, van Leeuwen B, Berns K, Mullenders J, Beijersbergen RL, Bernards R, Voorhoeve PM, Agami R. A genetic screen identifies PITX1 as a suppressor of RAS activity and tumorigenicity. Cell. 2005;121:849–858. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Calvisi DF, Ladu S, Conner EA, Seo D, Hsieh JT, Factor VM, Thorgeirsson SS. Inactivation of Ras GTPase-activating proteins promotes unrestrained activity of wild-type Ras in human liver cancer. J Hepatol. 2011;54:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jin H, Wang X, Ying J, Wong AH, Cui Y, Srivastava G, Shen ZY, Li EM, Zhang Q, Jin J, Kupzig S, Chan AT, Cullen PJ, Tao Q. Epigen-etic silencing of a Ca(2+)-regulated Ras GTPase-activating protein RASAL defines a new mechanism of Ras activation in human cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12353–12358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700153104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ohta M, Seto M, Ijichi H, Miyabayashi K, Kudo Y, Mohri D, Asaoka Y, Tada M, Tanaka Y, Ikenoue T, Kanai F, Kawabe T, Omata M. Decreased expression of the RAS-GTPase activating protein RASAL1 is associated with colorectal tumor progression. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:206–216. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bechtel W, McGoohan S, Zeisberg EM, Müller GA, Kalbacher H, Salant DJ, Müller CA, Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Methylation determines fibroblast activation and fibrogenesis in the kidney. Nat Med. 2010;16:544–550. doi: 10.1038/nm.2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kim JH, Lee HK, Takamiya K, Huganir RL. The role of synaptic GTPase-activating protein in neuronal development and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1119–1124. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01119.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Komiyama NH, Watabe AM, Carlisle HJ, Porter K, Charlesworth P, Monti J, Strathdee DJ, O’Carroll CM, Martin SJ, Morris RG, O’Dell TJ, Grant SG. SynGAP regulates ERK/MAPK signaling, synaptic plasticity, and learning in the complex with postsynaptic density 95 and NMDA receptor. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9721–9732. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09721.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Vazquez LE, Chen HJ, Sokolova I, Knuesel I, Kennedy MB. SynGAP regulates spine formation. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8862–8872. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3213-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Knuesel I, Elliott A, Chen HJ, Mansuy IM, Kennedy MB. A role for synGAP in regulating neuronal apoptosis. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:611–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Guo X, Hamilton PJ, Reish NJ, Sweatt JD, Miller CA, Rumbaugh G. Reduced expression of the NMDA receptor-interacting protein SynGAP causes behavioral abnormalities that model symptoms of Schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1659–1672. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Muhia M, Feldon J, Knuesel I, Yee BK. Appetitively motivated instrumental learning in SynGAP heterozygous knockout mice. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:1114–1128. doi: 10.1037/a0017118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Muhia M, Yee BK, Feldon J, Markopoulos F, Knuesel I. Disruption of hippocampus-regulated behavioural and cognitive processes by heterozygous constitutive deletion of SynGAP. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:529–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Krapivinsky G, Medina I, Krapivinsky L, Gapon S, Clapham DE. SynGAP-MUPP1-CaMKII synaptic complexes regulate p38 MAP kinase activity and NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic AMPA receptor potentiation. Neuron. 2004;43:563–574. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Rumbaugh G, Adams JP, Kim JH, Huganir RL. SynGAP regulates synaptic strength and mitogen-activated protein kinases in cultured neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4344–4351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600084103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Carlisle HJ, Manzerra P, Marcora E, Kennedy MB. SynGAP regulates steady-state and activity-dependent phosphorylation of cofilin. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13673–13683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4695-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hamdan FF, Gauthier J, Spiegelman D, Noreau A, Yang Y, Pellerin S, Dobrzeniecka S, Côté M, PerreauLinck E, Carmant L, D’Anjou G, Fombonne E, Addington AM, Rapoport JL, Delisi LE, Krebs MO, Mouaffak F, Joober R, Mottron L, Drapeau P, Marineau C, Lafrenière RG, Lacaille JC, Rouleau GA, J. L. MichaudSynapse to Disease Group Mutations in SYNGAP1 in autosomal nonsyndromic mental retardation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:599–605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Min W, Lin Y, Tang S, Yu L, Zhang H, Wan T, Luhn T, Fu H, Chen H. AIP1 recruits phosphatase PP2A to ASK1 in tumor necrosis factor-induced ASK1-JNK activation. Circ Res. 2008;102:840–848. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.168153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zhang H, Zhang H, Lin Y, Li J, Pober JS, Min W. RIP1-mediated AIP1 phosphorylation at a 14-3-3-binding site is critical for tumor necrosis factor-induced ASK1-JNK/p38 activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14788–14796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Luo D, He Y, Zhang H, Yu L, Chen H, Xu Z, Tang S, Urano F, Min W. AIP1 is critical in transducing IRE1-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress response. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11905–11912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710557200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Chen H, Toyooka S, Gazdar AF, Hsieh JT. Epigenetic regulation of a novel tumor suppressor gene (hDAB2IP) in prostate cancer cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3121–3130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208230200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Dote H, Toyooka S, Tsukuda K, Yano M, Ota T, Murakami M, Naito M, Toyota M, Gazdar AF, Shimizu N. Aberrant promoter methylation in human DAB2 interactive protein (hDAB2IP) gene in gastrointestinal tumour. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1117–1125. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Dote H, Toyooka S, Tsukuda K, Yano M, Ouchida M, Doihara H, Suzuki M, Chen H, Hsieh JT, Gazdar AF, Shimizu N. Aberrant promoter methylation in human DAB2 interactive protein (hDAB2IP) gene in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2082–2089. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Yano M, Toyooka S, Tsukuda K, Dote H, Ouchida M, Hanabata T, Aoe M, Date H, Gazdar AF, Shimizu N. Aberrant promoter methylation of human DAB2 interactive protein (hDAB2IP) gene in lung cancers. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:59–66. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Chen H, Tu SW, Hsieh JT. Down-regulation of human DAB2IP gene expression mediated by polycomb Ezh2 complex and histone deacetylase in prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22437–22444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Min J, Zaslavsky A, Fedele G, McLaugh-lin SK, Reczek EE, Raedt T De, Guney I, Strochlic DE, Macconaill LE, Beroukhim R, Bronson RT, Ryeom S, Hahn WC, Loda M, Cichowski K. An oncogene-tumor suppressor cascade drives metastatic prostate cancer by coordinately activating Ras and nuclear factor-kappaB. Nat Med. 2010;16:286–294. doi: 10.1038/nm.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]