Abstract

Introduction

Vascular targeted photodynamic therapy (VTP) with WST11 (TOOKAD® Soluble; STEBA Biotech, Luxembourg) is a form of tissue ablation that may be used therapeutically for localized prostate cancer (PCa). To study dosing parameters and associated treatment effects we undertook a prospective multicenter phase I/II trial of WST11 VTP for treatment of PCa

Methods

30 men with unilateral, low volume, Gleason 3+3 PCa were enrolled at 5 centers following local IRB approval. Light energy, fiber number, and WST11 dose were escalated to identify optimal dosing parameters for VTP hemiablation. Men were treated by VTP and evaluated by post-treatment MRI and biopsy. PSA, light dose index (LDI-defined as sum of fiber length/ desired treatment volume), toxicity, and quality of life parameters were recorded.

Results

Following dose escalation, 21 men received optimized dosing of 4 mg/kg WST11 200 J energy. On post-treatment biopsy, residual PCa was found in the treated lobe in 10 men, untreated lobe in 4, and both lobes in 1. When LDI ≥ 1, at optimal dosing, (n=15), 73.3% had a negative biopsy in the treated lobe. Six men undergoing retreatment, with optimal dose and LDI ≥ 1, had negative post-treatment biopsy. Minimal effects on urinary, sexual function, and overall quality of life, were observed.

Conclusions

Hemiablation of the prostate with WST11 VTP was well-tolerated and resulted in negative biopsy in the treated lobe for the majority of men. Dosing parameters and LDI appear related to tissue response as determined by MRI and biopsy. These parameters may serve as the basis for further prospective studies.

Keywords: Prostate Cancer, Focal Therapy, Photodynamic Therapy, Clinical Trial, Laser

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in tissue ablative strategies for focal therapy for localized prostate cancer (PCa)1–3. While early results of limited clinical trials have been promising, several obstacles remain before widespread adoption4. In addition to a lack of long-term oncologic outcomes, short-term challenges in trial design persist, including candidate selection, method of treatment guidance, optimal energy source, and appropriate endpoints for follow-up5,1,3.Several energy sources have been tested in the prostate, demonstrating variable outcomes in local tissue destruction and tolerability6–8, but there is limited data on the utilization of treatment planning and image correlation for evaluation of tissue necrosis9–12.

One well-studied and proven form of soft tissue ablation is photodynamic therapy (PDT), which refers to tissue destruction created by the interaction of a specific wavelength of light with a photosensitive agent9,13,14 Several advantages of PDT have been recognized, including lack of reliance on thermal energy dispersion or heat-sink effect15. WST11 (TOOKAD® Soluble; STEBA Biotech, Luxembourg) is a recently described photodynamic agent that is retained in the vascular compartment, and mediates ablation through localized generation of oxygen free-radicals, resulting in vascular thrombosis and local cellular apoptosis16–19 We undertook a prospective phase I/II multicenter trial of WST11 mediated vascular-targeted PDT (VTP) for the focal ablation of PCa.

Methods

Study Design

This was a multi-center phase I/II, non-randomised, open-label, trial conducted within 5 centers in the United States (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT0094681). Following approval by local institutional review boards, 30 men with serum PSA ≤ 10 ng/ml, clinical stage T1c/T2a, unilateral PCa demonstrated on a minimum 12 core transrectal prostate biopsy (PBx), who had been offered but refused traditional therapy, were enrolled. Men were excluded if biopsy Gleason score > 3+3, > 50% of sampled cores positive, bilateral disease, any core with cancer length > 5 mm, current PCa treatment, hormonal deprivation (excluding 5-alpha reductase inhibitors) or supplementation within 6 months, or previous TURP.

The primary objective of the study was to define the optimal drug and light dosage necessary to achieve negative biopsy in the treated lobe, through sequential escalation of drug dose, light fiber number, and energy, and to determine the safety and tolerability of WST11-mediated VTP. Secondary outcomes included quality of life, drug pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics.

Treatment Planning

Included men underwent multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI), centrally reviewed by an external committee, to determine necessary tissue volume to be treated to achieve hemi-ablation of the cancer-bearing lobe; to plan the number, length and position of light fibers to be utilized in treatment; to identify obvious radiographic presence of extra-capsular disease; but not for cancer diagnosis or localization.

Treatment and Follow-up

Treatment consisted of a unilateral hemi-ablation of the affected lobe. The procedure, performed using general anesthesia, has been previously described in detail10,14,15 In brief, VTP consisted of a single, 10 minute IV administration of the designated dose of WST11 followed immediately by a 20 minute light exposure interval. Light activation was delivered through transperineal interstitial optical fibers, placed prior to IV WST-11 administration under TRUS guidance in accordance with a previously devised mpMRI-based treatment plan. Laser light at 753 nm was delivered the designated energy level, using a multichannel diode laser (V-Gen Electro Optics Ltd, Israel, model 8CH-753 Mk II).

The pre-defined dose escalation scheme, not segregated by study site, consisted of either 2, 4, or 6 mg/kg WST11 activated with 200 or 300 J/cm light in a 3 + 3 dose escalation design to determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD). The decision to escalate to subsequent drug and/or light dose was determined by an independent data safety monitoring board (DSMB) after mpMRI obtained 1 week post-treatment and assessment of treatment-related adverse events in each escalation stratile.

Stopping rules for dose escalation were defined in case of dose limiting toxicity (DLT), significant adverse events (AEs), i.e. severe or serious drug-related AEs, changes in safety laboratory parameters defined as grade ≥ 2 according to National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for AEs (CTCAE), unexpected or atypical MRI findings, or deterioration in electrocardiogram (ECG) findings. DLT was defined as specific AEs graded as CTCAE grade ≥ 3 (hypotension and venous thrombosis) or grade ≥ 2 (photosensitivity related to interaction of light and drug, genito-urinary stricture/stenosis, rectal injury, infection and urinary retention). If ≥ 2 out of 3 (or ≥ 2 out of 6) patients at a particular drug and light dose combination had DLT, escalation was to be stopped and the previous drug and light dose was to be declared the MTD. When no further dose escalations were recommended by the DSMB, the recommended dose was to be expanded up to a maximum of 30 patients.

Men were followed for a total of 12 months with serial PSA, mpMRI, physical exam, quality of life assessment, and adverse event recording. Light density index (LDI), defined as the ratio between total light-emitting length of inserted laser fibers (cm) and the baseline desired volume of necrosis by planimetry (cm3) of targeted prostate, was calculated for each patient.

Volume and confluence of necrosis was assessed by post-treatment gadolinium enhanced mpMRI performed at 7 days and 6 months following treatment. Volume of non-perfused prostate tissue was calculated by planimetry and compared to intended volume of necrosis.

A follow-up 12-core PBx was obtained 6 months following treatment. Men with residual ipsilateral PCa, meeting initial study inclusion criteria, were offered a single repeat VTP procedure. The second treatment was conducted ≥ 6 weeks after the 6-month biopsy. Following repeat treatment, an additional 12 months of total follow-up was recorded, with follow-up biopsy at 6 months post-treatment.

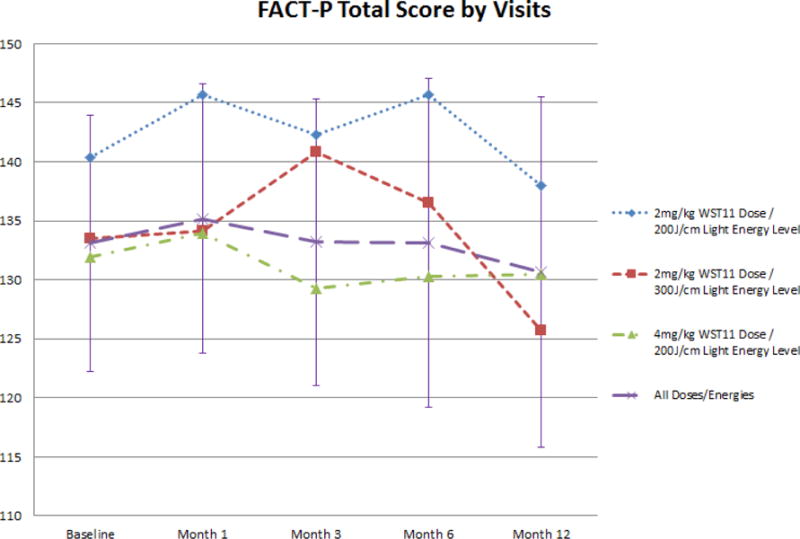

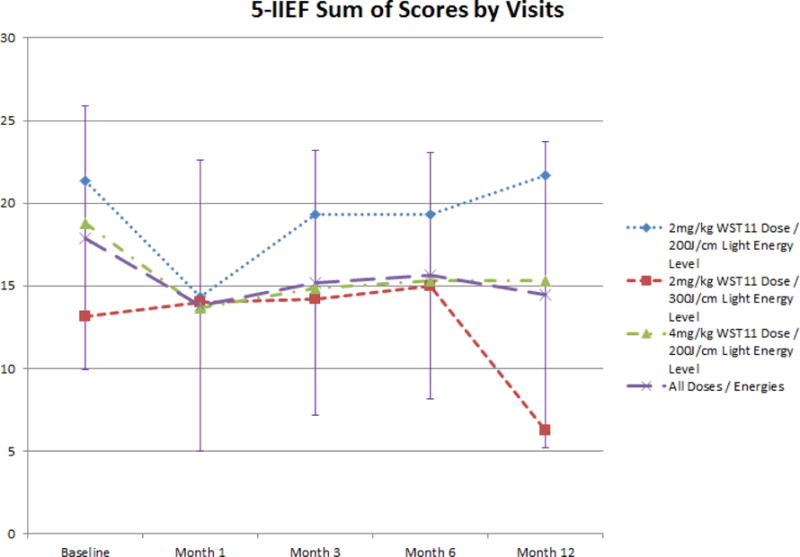

Urinary and erectile function prior to VTP, and at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post-treatment, were assessed using the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) quality of life questionnaires, respectively. Quality of life was assessed at the same time points using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - Prostate (FACT-P) Questionnaire.

Statistics

All analyses were descriptive and performed for the overall cohort and individual treatment groups (by WST11 dose and light energy dose). Descriptive statistics were calculated for quantitative variables; frequency counts by category were given for qualitative variables. Efficacy was analyzed by comparison of the relationship between drug dose/light energy dose and negative biopsies at Month 6, change from baseline in the proportion of viable prostate tissue as assessed by planar measurement of the area of ablation/non-perfused tissue using dynamic gadolinium MRI at Week 1 and Month 6, post-treatment changes in levels of PSA, and post-treatment changes in the IPSS, IIEF 5, and FACT P scores.

No sample size calculation was performed. The numbers of patients enrolled was based on the MTD determined during the study and the expansion of the MTD cohort. The expansion cohort was planned for up to 30 patients in total.

Results

A total of 30 men enrolled and treated in the study were included in safety and efficacy analysis (Table 1). Two patients discontinued the study before the 12-month follow-up (1 due to withdrawal of consent and 1 because the patient moved away). During the dose escalation phase, 3 patients received single fiber, 2 mg/kg WST11, 200 J/cm light and 6 patients received 2 mg/kg WST11, 300 J/cm light (single or multifiber). Based upon cumulative data from PCM202 and concurrent ongoing European trials20, dose escalation was discontinued following the multifiber - 2mg/kg WST11 - 300 J/cm dose group by the DSMB and the trial sponsor, as it was felt that reproducible, confluent necrosis could be achieved at an optimal dosing of multiple laser fibers, 4 mg/kg WST11, and 200 J/cm energy, and that further escalation would risk toxicity without perceived benefit in efficacy. A total of 21 patients were thus treated at the optimal dose.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| 2 mg/kg 200 J/cm (N=3) | 2 mg/kg 300 J/cm (N=6) | 4 mg/kg 200 J/cm (N=21) | All Doses / Energies (N=30) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | (n=3) | (n=6) | (n=21) | (n=30) | |

| Mean ± SD | 58.0 ± 9.8 | 63.8 ± 9.2 | 61.4 ± 7.3 | 61.6 ± 7.8 | |

| Median | 61.0 | 64.5 | 63.0 | 63.0 | |

| Range | 47–66 | 48–74 | 49–73 | 47–74 | |

|

| |||||

| Race | |||||

| Asian | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.8%) | 1 (3.3%) | |

| Black | 3 (100%) | 4 (66.7%) | 7 (33.3%) | 14 (46.7%) | |

| Caucasian | 0 | 2 (33.3%) | 12 (57.1%) | 14 (46.7%) | |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.8%) | 1 (3.3%) | |

|

| |||||

| Time since biopsy (months) | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.21 ± 0.35 | 3.3 ± 1.16 | 4.8 ± 2.1 | 4.24± 2.03 | |

| Median | 2.1 | 3.5 | 5.0 | 3.8 | |

| Range | 1.9–2.6 | 1.5–4.8 | 1.5–8.8 | 1.5–8.8 | |

|

| |||||

| Stage at diagnosis (TNM) | |||||

| T1C | 3 (100%) | 5 (83.3%) | 18 (85.7%) | 26 (86.7%) | |

| T1CN0MX | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 1 (3.3%) | |

| T2A | 0 | 0 | 3 (14.3%) | 3 (10%) | |

|

| |||||

| Number of positive cores | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | |

| Median | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Range | 1–3 | 1–2 | 1–3 | 1–3 | |

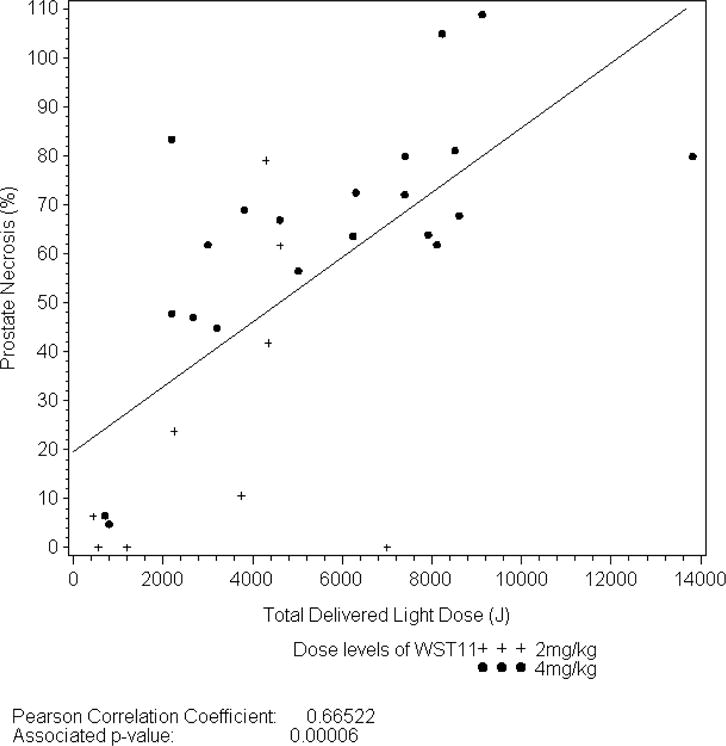

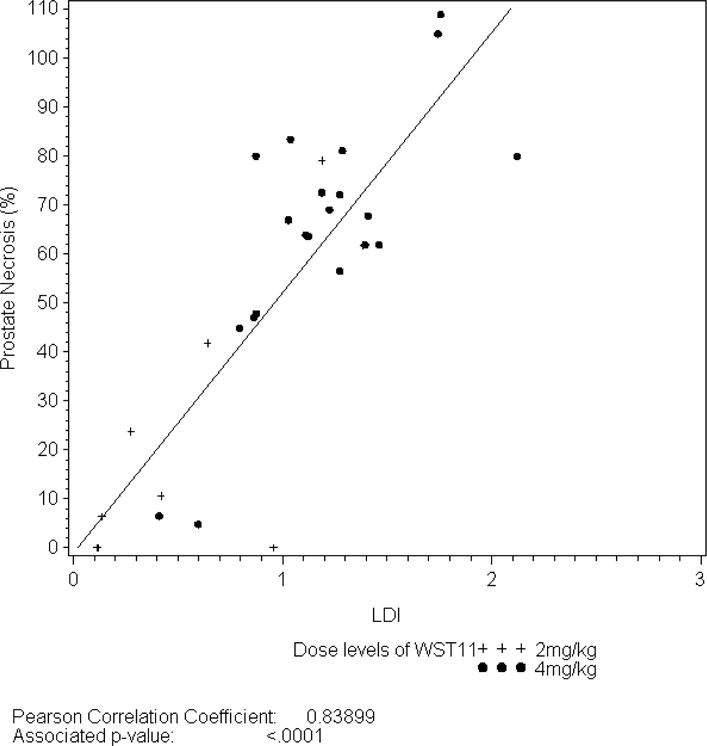

Evaluation of 1-week post-treatment DCE-MRI studies revealed median non-perfused prostate tissue was 52.3% (± 31.9) of the intended tissue ablation (Table 2), and just over half of the patients (56.7%) had extra-prostatic treatment extension observed. Among 21 men receiving the optimal dosing parameters, the mean ablation effect was 64.1% (± 25.3) of intended. Among 17 men with LDI ≥ 1, mean ablation was 73.9% (± 14.7) of intended volume. For men treated with the optimal treatment parameters and LDI ≥ 1 (n=15), the mean treatment effect was 74.3% (± 15.3) of intended. A direct correlation was observed between percent ablation effect as determined by DCE-MRI and light energy (figure 1a) as well as LDI (figure 1b).

Table 2.

Prostate Necrosis Percentage (%) as estimated by MRI at Day 7

| 2 mg/kg 200 J/cm (N=3) | 2 mg/kg 300 J/cm (N=6) | 4 mg/kg 200 J/cm (N=21) | All Doses / Energies (N=30) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | (n=3) | (n=6) | (n=21) | (n=30) |

| Mean ± SD | 46.9 ± 41.6 | 13.8 ± 16.3 | 64.1 ± 25.3 | 52.3 ± 31.9 |

| Median | 61.6 | 8.5 | 66.9 | 61.9 |

| Range | 0.0–79.1 | 0.0–41.8 | 4.8–108.9 | 0.0–108.9 |

|

| ||||

| LDI < 1 | (n=1) | (n=6) | (n=6) | (n=13) |

| Mean ± SD | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 13.8 ± 16.3 | 38.5 ± 28.6 | 24.1 ± 25.6 |

| Median | 0.0 | 8.5 | 46.0 | 10.6 |

| Range | 0.0–0.0 | 0.0–41.8 | 4.8–80.0 | 0.0–80.0 |

|

| ||||

| LDI ≥ 1 | (n=2) | (n=0) | (n=15) | (n=17) |

| Mean ± SD | 70.4 ± 12.4 | 74.3 ± 15.3 | 73.9 ± 14.7 | |

| Median | 70.4 | 69.0 | 69.0 | |

| Range | 61.6–79.1 | 56.5–108.9 | 56.5–108.9 | |

|

| ||||

| p-value* | 0.6026 | 0.0168 | 0.0003 | |

|

| ||||

| Extraprostatic Necrosis | (n=3) | (n=6) | (n=21) | (n=30) |

|

| ||||

| Yes | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | 14 (66.7%) | 17 (56.7%) |

| No | 2 (66.7%) | 4 (66.7%) | 7 (33.3%) | 13 (43.3%) |

Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test for (LDI < 1 vs. LDI >= 1)

Figure 1a.

Relationship between Energy Delivery and Prostate Necrosis at Day 7.

Figure 1b.

Relationship between LDI and Prostate Necrosis at Day 7

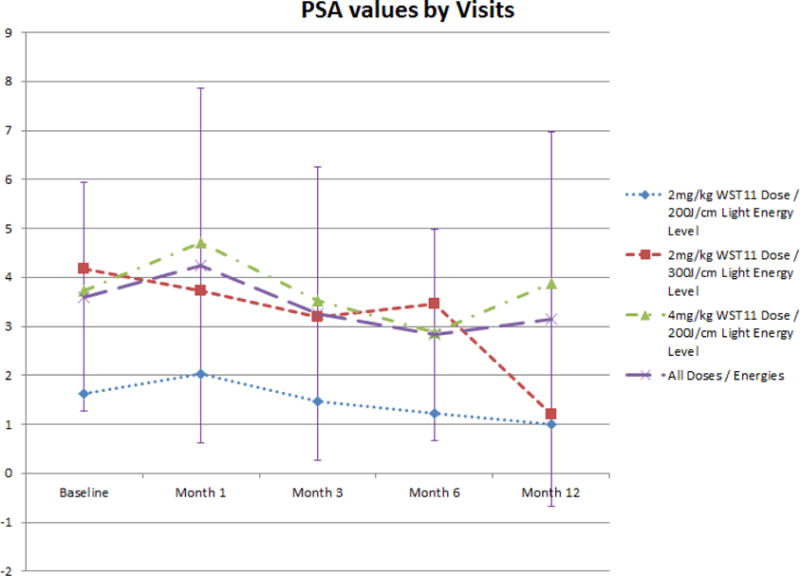

15 men had residual cancer on follow-up 6 month biopsy (Table 3). Cancer was found within the treated lobe in 10 men, the untreated lobe in 4 men, and in both lobes in one man. Among all men with LDI ≥ 1 (n=17), 6 men had residual cancer on biopsy, of whom 4 had cancer in the treated lobe. PSA values were generally unaffected following VTP (figure 2), with a mean reduction of 0.11 ng/ml by 12 months. 9/11 men with residual cancer in the treated lobe qualified for re-treatment per trial criteria of whom 7 opted for re-treatment of the ipsilateral lobe. In 6/7 men, LDI ≥ 1 was achieved. On 6-month biopsy following re-treatment, all 7 patients had a negative biopsy. Following retreatment, a total of 26 of 30 men had a negative biopsy in the treated lobe, and 22 of 30 treated men had a negative biopsy in both lobes.

Table 3.

Prostate Biopsy Results by LDI at Month 6

| 2 mg/kg 200 J/cm | 2 mg/kg 300 J/cm | 4 mg/kg 200 J/cm | All Doses / Energies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Biopsy Results in the treated lobe (Primary End-point)

| ||||

| Overall | (N=3) | (N=6) | (N=21) | (N=30) |

| Negative | 3 (100%) | 3 (50.0%) | 13 (61.9%) | 19 (63.3%) |

|

| ||||

| Exact 95% CI** | [29.2%;100%] | [11.8%;88.2%] | [38.4%;81.9%] | [43.9%;80.1%] |

|

| ||||

| Positive | 0 | 3 (50.0%) | 8 (38.1%) | 11 (36.7%) |

|

| ||||

| LDI < 1 | (n=1) | (n=6) | (n=6) | (n=13) |

| Negative | 1 (100%) | 3 (50.0%) | 2 (33.3%) | 6 (46.2%) |

|

| ||||

| Exact 95% CI** | [2.5%;100%] | [11.8%;88.2%] | [4.3%;77.7%] | [19.2%;74.9%] |

|

| ||||

| Positive | 0 | 3 (50.0%) | 4 (66.7%) | 7 (53.8%) |

|

| ||||

| LDI ≥ 1 | (n=2) | (n=0) | (n=15) | (n=17) |

| Negative | 2 (100%) | – | 11 (73.3%) | 13 (76.5%) |

|

| ||||

| Exact 95% CI** | [15.8%;100%] | – | [44.9%;92.2%] | [50.1%;93.2%] |

|

| ||||

| Positive | 0 | – | 4 (26.7%) | 4 (23;5%) |

|

| ||||

|

Biopsy Results in the whole prostate including untreated lobes (Exploratory Analysis)

| ||||

| Overall | (N=3) | (N=6) | (N=21) | (N=30) |

| Negative | 3 (100%) | 2 (33.3%) | 10 (47.6%) | 15 (50.0%) |

| Positive | 0 | 4 (66.7%) | 11 (52.4%) | 15 (50.0%) |

|

| ||||

| Treated Lobe Positive | 0 | 3 (50.0%) | 8 (38.1%) | 11 (36.7%) |

| Contralateral Positive | 0 | 2 (33.3%*) | 4 (19.0%*) | 6 (20.0%*) |

|

| ||||

| LDI < 1 | (n=1) | (N=6) | (N=6) | (n=13) |

| Negative | 1 (100%) | 2 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 4 (30.8%) |

| Positive | 0 | 4 (66.7%) | 5 (83.3%) | 9 (69.2%) |

|

| ||||

| Treated Lobe Positive | 0 (0%) | 3 (50.0%) | 4 (66.7%) | 7 (53.8%) |

| Contralateral Positive | 0 (0%) | 2 (33.3%*) | 2 (33.3%*) | 4 (46.2%*) |

|

| ||||

| LDI ≥ 1 | (n=2) | (n=0) | (n=15) | (n=17) |

| Negative | 2 (100%) | – | 9 (60.0%) | 11 (64.7%) |

| Positive | 0 | – | 6 (40.0%) | 6 (35.3%) |

|

| ||||

| Treated Lobe Positive | 0 (0%) | – | 4 (26.7%) | 4 (23.5%) |

| Contralateral Positive | 0 (0%) | – | 2 (13.3%) | 2 (11.8%) |

Cases with bilateral cancer on biopsy can result in cumulated percentages >100%

For the percentage of patients with negative biopsy assessment.

Figure 2.

PSA kinetics following VTP

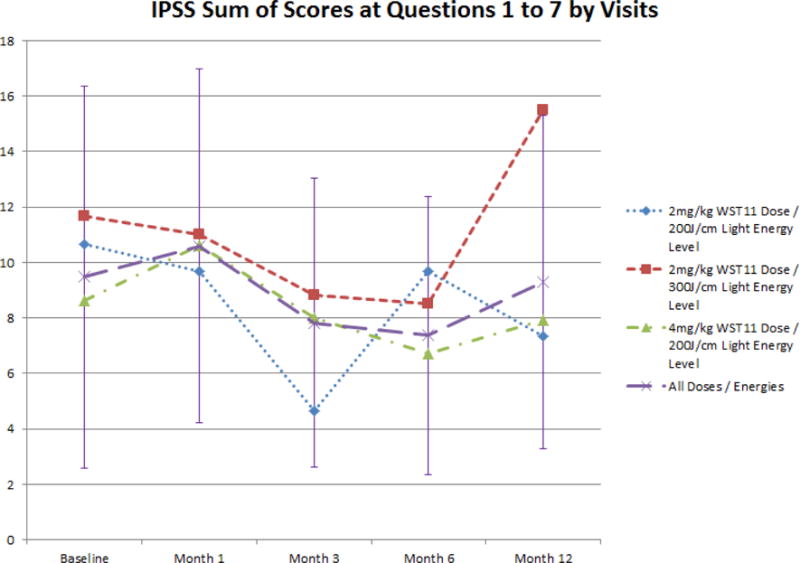

Minimal, often transient, effects on urinary and sexual function, and overall quality of life, were observed (figures 3 and 4). Sexual function declined by 12 months for the whole cohort, possibly related to the VTP procedure or secondary treatment figure 3b). Adverse events related to treatment were reported frequently (table 4), but no DLT, SAE, or death was reported.

Figure 3a.

Evolution of IPSS Sum of Scores for Questions 1 to 7 following VTP

Figure 4.

Evolution of FACT-P total score following VTP

Figure 3b.

Evolution of 5-IIEF Sum of Scores following VTP

Table 4.

Number of Patients with Related AEs by Preferred Term (Safety analysis set)

| AE | Overall | Related to Study Drug | Related to Study Device | Related to Technical Procedure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematuria | 9 | 5 | 9 | 6 |

| Micturition urgency | 9 | 4 | 9 | 5 |

| Perineal pain | 8 | 2 | 8 | 3 |

| Dysuria | 7 | 2 | 7 | 2 |

| Urinary retention | 7 | 1 | 6 | 5 |

| Erectile dysfunction | 6 | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| Pollakiuria | 4 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Ecchymosis | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Constipation | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Anorectal discomfort | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Hematospermia | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Back pain | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Urinary incontinence | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Incontinence* | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Urinary tract infection | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Groin pain | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Penile pain | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Headache | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Nausea | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

SOC Renal and urinary disorders.

Discussion

In summary, this first, early-phase, prospective multicenter focal therapy study to be undertaken in the United States demonstrated safety, tolerability and efficacy of WST-11 VTP for soft tissue ablation in cancer-bearing prostate tissue. Moreover, an optimal treatment condition (LDI ≥ 1) was achieved in 17 of the 30 patients enrolled, across a range of energy exposures. This resulted in a 74% ablation of the target volume as determined by a post-treatment MRI. This conferred a cancer free status in just over 70% of patients treated under optimal conditions Treatment was extremely well tolerated in the current study. No SAE or dose-limiting toxicity was observed and no significant systemic effects were identified. Though some degree of extraprostatic treatment effect was observed in a subset of men there was no secondary associated SAE or irreversible toxicity acutely or in follow up. Overall quality of life appeared minimally affected by the intervention based on the patient-reported outcomes.

In the study of VTP conducted by Moore, et al, similar conclusions regarding dose, efficacy, and safety were made10. Among men with LDI > 1, 83% were observed to have negative biopsy, as compared to 31.3% with LDI < 1. In that study, the overall rate of negative biopsy was comparable to ours when accounting for small numbers. While the rate of negative biopsy after one treatment is relatively low (63.3%), in our study, as compared to previous series of hemi-ablation using other energies, the small numbers preclude direct comparison. It is possible that the learning curve, the uncertainty regarding potential toxicity, and the number of new operators led to a more conservative or incomplete treatment. The option of re-treating is a major advantage of ablative technologies, and can improve overall treatment outcomes, as it did in this case, with 86.7% of men demonstrating negative biopsy in the treated lobe after two treatments, comparable to previously published reports of hemiablation2,6,21–24.

It is possible that the low toxicity observed in our study was, in part, explained by the known mechanism of tissue destruction. WST11mediated VTP creates local tissue destruction through non-thermal vascular-targeted effects by a previously described biochemical mechanism of action triggered by the contact of drug and light16–19. Radical oxygen and nitrogen species, are created which secondarily induce permanent vascular thrombosis and a propagation of oxidative stress mediated cellular apoptosis into the tissues starting from the blood vessels14,17,18. This novel process is in direct contradistinction to thermal dispersion from heat-sink effects caused by perfusing blood vessels. While this mechanism benefits from non-selective thrombosis of all blood vessels treatment zone, the adequacy of tissue destruction and the extent of apoptosis cannot be assessed in this study beyond the clinical endpoints utilized. Follow-up MRI obtained at 7 days following treatment demonstrated both confluent and contoured non-perfused tissue within the intended region of treatment among men receiving optimal drug and light dose, and adequate LDI, confirming the complete nature of vascular thrombosis.

Another novel aspect of this type of therapy is the incorporation of treatment planning from preoperative imaging and the intent for ablation based on volume. It seems likely that this contributed to the low rates of extraprostatic necrosis. Planning can only be done if there exists a reasonably predictable correlation between dose and effect. The relationship between tissue ablation effects in DCE-MRI and LDI was found to be quite good in this regard and supports this approach. This aspect of the technique appears favorable, allowing for target volume to serve as the main dependent variable when determining the number and length of fibers required for a given case.

In this study, a positive post-treatment biopsy in the treated lobe could be considered a failure of treatment, while a positive biopsy in the untreated lobe would likely be a failure of baseline staging. Men with cancer identified to be unilateral on 12 core trans-rectal biopsy carry a very high likelihood of harboring bilateral malignancy25. As pre-treatment mpMRI was utilized purely for treatment planning in this study, more accurate staging, presumably through the localization of disease by mpMRI, could likely reduce the numbers of positive post-treatment biopsies noted outside of the treatment zone, and allow better evaluation of the relationship of treatment planning and treatment failure.26,27 mpMRI in treatment planning has been shown to be highly sensitive in the detection of residual tumor following VTP.28

In addition to the method of candidate selection, additional limitations of the study design and interpretation include small sample size, potential for learning curve effects on quality of treatment given the small number of patients at individual centers, and the lack of long-term follow-up to determine true efficacy. Despite the limitations, the study demonstrates that VTP focal ablation in men with localized PCa is feasible, safe, offers potential treatment of localized PCa with relatively minimal effects on quality of life. Further evaluation of oncologic efficacy through larger, randomized cohort studies and through modified selection criteria is warranted. The results of two, phase III studies conducted in Europa (PCM301; NCT01310894) and Latin America (PCM304; NCT01875393) to confirm the efficacy and safety profile of the technique are expected in the near term.

Conclusions

TOOKAD® Soluble VTP focal therapy of the prostate is feasible and appears safe in this limited study. Treatment results in relatively minimal effects on quality of life in short term follow-up. Treatment planning through use of MRI assessment of intended treatment volume, and application of LDI, can result in reproducible, confluent tissue destruction in the intended treatment zone.

Acknowledgments

We would like to take this opportunity to thank the men that took part in this study. The study was designed and funded by STEBA Biotech, Luxembourg. The monitoring, data-management and pharmacovigilance were conducted by Aptiv Pharma, USA.

Key of Definitions for Abbreviations

- VTP

Vascular Targeted Photodynamic Therapy

- PCa

Prostate Cancer

- PBx

Prostate Biopsy

- mpMRI

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate

- MTD

Maximum tolerated dose

- DLT

Dose limiting toxicity

- DSMB

Data safety monitoring board

- AEs

Significant adverse events

- CTCAE

Common Terminology Criteria for AEs

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- LDI

Light Density Index

- IPSS

International Prostate Symptom Score

- IIEF-5

Index of Erectile Function

- FACT-P

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - Prostate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Samir S. Taneja receives research support from the Joseph and Diane Steinberg Charitable Trust.

Jonathan Coleman receives research support from grant funding provided by the Thompson Foundation.

Mark Emberton holds National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator status and receives research support from the United Kingdom’s NIHR UCLH/UCL Biomedical Research Centre.

References

- 1.Taneja SS, Mason M. Candidate selection for prostate cancer focal therapy. J Endourol. 2010;24:835–841. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah TT, Ahmed H, Kanthabalan A, et al. Focal cryotherapy of localized prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2014;14(11):1337–1347. doi: 10.1586/14737140.2014.965687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed HU, Berge V, Bottomley D, et al. Can we deliver randomized trials of focal therapy in prostate cancer? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014:1–10. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarow JP, Ahmed HU, Choyke PL, Taneja SS, Scardino PT. Partial Gland Ablation for Prostate Cancer: Report of a Food and Drug Administration, American Urological Association, and Society of Urologic Oncology Public Workshop. Urology. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donaldson IA, Alonzi R, Barratt D, et al. Focal Therapy: Patients, Interventions, and Outcomes-A Report from a Consensus Meeting. Eur Urol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahn D, de Castro Abreu AL, Gill IS, et al. Focal Cryotherapy for Clinically Unilateral, Low-Intermediate Risk Prostate Cancer in 73 Men with a Median Follow-Up of 3.7 Years. Eur Urol. 2012;62(1):55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.03.006. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Onik G, Mikus P, Rubinsky B. Irreversible electroporation: implications for prostate ablation. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2007;6:295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oto A, Sethi I, Karczmar G, et al. MR Imaging-guided Focal Laser Ablation for Prostate Cancer: Phase I Trial. Radiology. 2013;267(3):932–940. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arumainayagam N, Moore CM, Ahmed HU, Emberton M. Photodynamic therapy for focal ablation of the prostate. World J Urol. 2010;28:571–576. doi: 10.1007/s00345-010-0554-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore CM, Azzouzi AR, Barret E, et al. Determination of optimal drug dose and light dose index to achieve minimally invasive focal ablation of localized prostate cancer using WST11-Vascular Targeted Photodynamic (VTP) therapy. BJU Int. 2014:n/a–n/a. doi: 10.1111/bju.12816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu CC, Hsu H, Pickett B, et al. Feasibility of MR imaging/MR spectroscopy-planned focal partial salvage permanent prostate implant (PPI) for localized recurrence after initial PPI for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson SRH, Weersink RA, Haider MA, et al. Treatment planning and dose analysis for interstitial photodynamic therapy of prostate cancer. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54(8):2293–2313. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/8/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bozzini G, Colin P, Betrouni N, et al. Efficiency of 5-ALA mediated photodynamic therapy on hypoxic prostate cancer: A preclinical study on the dunning R3327-AT2 rat tumor model. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2013;10:296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trachtenberg J, Bogaards A, Weersink RA, et al. Vascular targeted photodynamic therapy with palladium-bacteriopheophorbide photosensitizer for recurrent prostate cancer following definitive radiation therapy: assessment of safety and treatment response. J Urol. 2007;178(5):1974–1979. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.07.036. discussion 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azzouzi AR, Barret E, Moore CM, et al. TOOKAD® Soluble vascular-targeted photodynamic (VTP) therapy: Determination of optimal treatment conditions and assessment of effects in patients with localised prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2013;112:766–774. doi: 10.1111/bju.12265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chevalier S, Anidjar M, Scarlata E, et al. Preclinical study of the novel vascular occluding agent, WST11, for photodynamic therapy of the canine prostate. J Urol. 2011;186(1):302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madar-Balakirski N, Tempel-Brami C, Kalchenko V, et al. Permanent occlusion of feeding arteries and draining veins in solid mouse tumors by vascular targeted photodynamic therapy (VTP) with Tookad. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e10282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashur I, Goldschmidt R, Pinkas I, et al. Photocatalytic generation of oxygen radicals by the water-soluble bacteriochlorophyll derivative WST11, noncovalently bound to serum albumin. J Phys Chem A. 2009;113(28):8027–8037. doi: 10.1021/jp900580e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazor O, Brandis A, Plaks V, et al. WST11, a novel water-soluble bacteriochlorophyll derivative; cellular uptake, pharmacokinetics, biodistribution and vascular-targeted photodynamic activity using melanoma tumors as a model. Photochem Photobiol. 81(2):342–351. doi: 10.1562/2004-06-14-RA-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azzouzi A-R, Lebdai S, Benzaghou F, Stief C. Vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy with TOOKAD(®) Soluble in localized prostate cancer: standardization of the procedure. World J Urol. 2015;33(7):937–944. doi: 10.1007/s00345-015-1535-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmed HU, Hindley RG, Dickinson L, et al. Focal therapy for localised unifocal and multifocal prostate cancer: A prospective development study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:622–632. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70121-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bahn DK, Silverman P, Lee F, Badalament R, Bahn ED, Rewcastle JC. Focal prostate cryoablation: initial results show cancer control and potency preservation. J Endourol. 2006;20:688–692. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.20.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Fegoun AB, Barret E, Prapotnich D, et al. Focal therapy with high-intensity focused ultrasound for prostate cancer in the elderly. A feasibility study with 10 years follow-up. Int Braz J Urol. 2011;37:212–213. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382011000200008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=21557838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barret E, Ahallal Y, Sanchez-Salas R, et al. Morbidity of focal therapy in the treatment of localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2013;63(4):618–622. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tareen B, Godoy G, Sankin A, Temkin S, Lepor H, Taneja SS. Can contemporary transrectal prostate biopsy accurately select candidates for hemi-ablative focal therapy of prostate cancer? BJU Int. 2009;104:195–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenkrantz AB, Scionti SM, Mendrinos S, Taneja SS. Role of MRI in minimally invasive focal ablative therapy for prostate cancer. Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197 doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haider MA, Davidson SRH, Kale AV, et al. MR Imaging Appearance after Vascular Targeted Photodynamic Therapy with Palladium-Bacteriopheophorbide. Radiology. 2007;244(1):196–204. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2441060398. file:///C:/Users/Neil/Documents/Urology/Focaltherapy/HaiderPDT2007.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barrett T, Davidson SRH, Wilson BC, Weersink RA, Trachtenberg J, Haider MA. Dynamic contrast enhanced MRI as a predictor of vascular-targeted photodynamic focal ablation therapy outcome in prostate cancer post-failed external beam radiation therapy. Can Urol Assoc J. 2014;8(9–10):E708–E714. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]