Abstract

Addressing inaccurate penicillin allergies is encouraged as part of antibiotic stewardship in the inpatient setting. However, implementing interventions targeted at the 10–15% of inpatients reporting a prior penicillin allergy can pose substantial logistic challenges. We implemented a computerized guideline for patients with reported beta-lactam allergy at five hospitals within a single healthcare system in the Boston area. In this paper, we describe our implementation roadmap, including both successes achieved and challenges faced. We explain key implementation steps, including assembling a team, stakeholder engagement, developing or selecting an approach, spreading the change, establishing measures, and measuring impact. The objective is to detail the lessons learned while empowering others to be part of this important, multi-disciplinary work to improve the care of patients with reported beta-lactam allergies.

Keywords: policy, guideline, stewardship, adverse drug reaction, hypersensitivity, allergy, beta-lactam, drug, allergy, penicillin, test dose, graded challenge, quality improvement

INTRODUCTION

Approximately half of all hospitalized patients receive antibiotics, and the 10–15% of inpatients with prior reported penicillin allergy receive broader-spectrum, often less effective or more toxic antibiotics.1–3 Patients who have a reported beta-lactam allergy, and who are treated with a non-beta-lactam, have an increased risk of treatment failure4 and adverse events.5 Often non-beta-lactam alternative antibiotics are used, even among patients who have infections for which first-line treatment is a beta-lactam antibiotic.3,6 The over-use of broad-spectrum antibiotics contributes to growing antimicrobial resistance for the hospital and community, and has been associated with an increased odds of resistant organisms and Clostridium difficile infections for patients reporting penicillin allergy.7

Prior data from both outpatient8,9 and inpatient10–12 settings support that the vast majority of patients who report an allergy to beta-lactam antibiotics are not truly allergic. Indeed, more than 95% of patients who report penicillin allergy, and are tested, are found to tolerate penicillins and related beta-lactams.8–13 Because of this large discrepancy, penicillin allergy evaluation in some form is encouraged by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,14 the National Quality Forum,15 the American Board of Internal Medicine,16 the Infectious Disease Society of America,17 the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology in America,17 and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.18 As guidelines and position statements accrue, allergists have a unique opportunity to collaborate with colleagues from infectious diseases, pharmacy, and quality improvement to design and implement system-based solutions to help improve antibiotic choices among patients with reported penicillin allergy.

A variety of methods to address inpatient penicillin allergies have been previously proposed. Programs with routine penicillin skin testing, performed by internists, allergists, and pharmacists were previously implemented with varying success.10,12,19–23 Other groups used routine allergy consultation, with or without patient screening performed by pharmacists.11,24 Alternative approaches have targeted penicillin allergy evaluation only for inpatients with particular infections,21 or those prescribed particular beta-lactam alternative drugs (e.g., aztreonam).11,25

Generally, four pathways towards achieving healthcare improvements have been defined: (1) standardization, (2) coordination, (3) improving treatment decisions, and (4) prevention.26 In this article, we present our experience designing and performing a multi-site implementation project that targeted all of these pathways. We used a standardized approach to patients reporting beta-lactam allergies that included coordination between clinical providers, pharmacy, and nursing in order to improve treatment decisions and prevent unnecessary downstream adverse events. The intervention was a computerized guideline that engaged non-allergy providers to clinically assess the patients’ penicillin or cephalosporin allergy history to safely prescribe beta-lactam antibiotics.

In this paper, we present key principles in designing the guideline and tools that we used, and explain effective implementation steps: assembling a team, gaining stakeholder engagement, developing or selecting an approach, spreading the change, establishing measures, and evaluating impact. The objective is to detail the lessons we learned in this process, as well as empower allergists to join multi-disciplinary teams across the United States tasked to improve the care of patients with reported beta-lactam allergies.

1. Forming the Team and Stakeholder Engagement

Generally, improvement teams should include specific individual roles, such as management sponsor, team leader, subject matter expert, team member, and improvement advisor/project manager.27 While the optimal team structure for improvement is often a dedicated team, most teams, including ours, must recruit part-time team members who add this project into any available time.26 Programs that affect the choice of antimicrobials have implications for a broad group of providers. Each stakeholder must have both a role in the program as well as a vested interest in the success of the program. An effective implementation team should include, at a minimum:

Executive Sponsor (e.g., hospital leadership, quality/safety leadership, antibiotic stewardship leadership). The executive sponsor can use their authority to allocate resources, remove barriers, and provide liaisons.27 A sponsor is also important to help deliver the message and inspire change. The sponsor is not a day-to-day participant, but periodically reviews the implementation team’s progress. The right executive sponsor may be motivated to support this initiative because all hospitals report healthcare-associated infections to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Healthcare Safety Network.28 Public reporting of healthcare-associated infections has not only reputational impact, but is also linked to reimbursement from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.29,30 In addition, as of January, 2017, the Joint Commission required hospitals to implement antimicrobial stewardship programs to improve antibiotic use and mitigate the emergence of antibiotic-resistance. This project could be used by hospitals to demonstrate compliance with that standard.31

Allergy/Immunology Clinical Lead. In order to devise a safe and effective program, the team requires allergist expertise, as general inpatient providers have limited drug allergy knowledge.3,32–34 The education about penicillin allergy and allergy procedures, and development of hospital protocols and policies should come from those with specialty level knowledge and experience. Programs without access to allergy expertise should collaborate with hospitals that have allergists, or consider adoption of an intervention that has been previously vetted and evaluated. Evaluating patients with drug allergies is within the scope of allergy practice and for a community allergist, the hospital relationship would likely result in increased outpatient referrals. Additionally, collaborative quality improvement activities can be used for Maintenance of Certification credits for boards, such as the American Board of Internal Medicine and the American Board of Allergy and Immunology.

Infectious Diseases Clinical Lead. The role of the infectious diseases clinical lead is to serve as the subject matter expert for antibiotic usage, including identifying stewardship priorities such as targeted patient groups, infections, and/or drugs. Antibiotic Stewardship Committees (ASCs),17,35,36 often comprised of leaders in medicine, infectious diseases, and pharmacy, perform interventions designed to improve and measure the appropriate use of antibiotic agents by promoting the selection of the optimal antibiotic. ASCs also may address patient reported penicillin allergy.17,35 Because ASCs are regularly tracking antibiotic usage, and are soon to be a Joint Commission standard,31 they are a natural place to identify engaged team members and leverage existing hospital resources.

Pharmacy Lead. Pharmacists are integral for day-to-day medication safety. They review medication orders, and check drugs against prior reported allergies to avert potentially iatrogenic allergic reactions. Given their involvement in allergy checking and drug verification and processing, pharmacists can play a key role in identifying patients who require allergy clarification, and those at high risk of complications because of unnecessary alternative antibiotic use. Pharmacy cooperation is additionally needed for streamlined operations of inpatient skin testing, test dosing, and desensitization. Support of pharmacy leadership may be gained by projecting the favorable impact of this type of project on the pharmacy budget. For example, there may be a cost savings if there is a shift away from use of aztreonam (about $240/day) towards use of cefepime (about $40/day).37

Nursing Lead. To safely change inpatient practice, and successfully introduce nurses to new procedures (e.g., skin tests, test doses, desensitizations), nursing engagement is crucial. Nursing comfort with allergy assessments and procedures are important to adoption. Nurses additionally have the greatest grasp of inpatient floor operations and can provide valuable insight into implementation feasibility and staffing needs. After the nursing lead gains comfort with the intervention(s), they become instrumental in leading nursing education on patient care units. This nursing leadership role is suitable for a nurse who already has an administrative position in education or quality and safety.

Program Support/Data Analyst. To organize implementation, as well as understand the policy’s impact, project managers and data analysts are useful team members, if available.

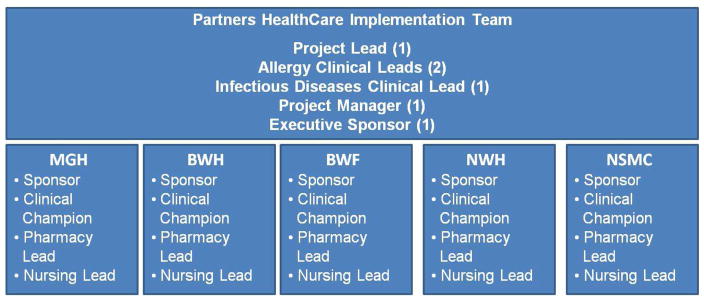

In March, 2016, we assembled a multidisciplinary team at each of five hospitals to implement a computerized guideline for patients with beta-lactam allergies. While united in ownership (i.e., Partners HealthCare System), each of these hospitals functions independently with distinct policies, systems, and administrators. Hospitals included two academic tertiary care referral centers with on-site Allergy/Immunology and allergy on-call services -- the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) -- and three community teaching hospitals, Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital (BWF), Newton Wellesley Hospital (NWH), and North Shore Medical Center (NSMC, Table I). Each hospital team included an executive sponsor, and clinical, pharmacy, and nursing leaderships (Figure 1). The clinical leader was termed the “Clinical Champion.” Given the system-wide implementation, we additionally had an umbrella structure with a Partners HealthCare Team comprised of an overall executive sponsor, additional clinical leaders, and a project manager.

Table I.

Hospital Sites for Implementation

| MGH | BWH | BWF | NWH | NSMC* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Type | Academic | Academic | Community† | Community‡ | Community |

| Massachusetts Location | Boston | Boston | Boston | Newton | Salem/Lynn |

| Number of Beds§ | 1,043 | 851 | 138 | 282 | 431 |

| Number of Annual Admissions|| | 49,799 | 41,804 | 9,282 | 14,796 | 17,758 |

| Antibiotic Stewardship Program | Yes | Yes | Yes | No** | No** |

| Antibiotic Stewardship Program Members | Physicians, Pharmacists, Infection Control, Clinical Microbiology | Physicians, Pharmacists, Infection Control, Clinical Microbiology | Infectious Diseases Physicians, Pharmacists | -- | -- |

| Allergy/Immunology Consultation Available | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Inpatient Penicillin Skin Testing Available | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Desensitization Available | Specific medical floors and ICUs | Specific medical floors and ICUs | Transfer to BWH arranged for desensitization, except one day a week availability in BWF ICU | ICUs | ICUs |

NSMC is comprised of Salem Hospital and Union Hospital

Housestaff from BWH

Housestaff from MGH

2014 Center for Health Information and Analysis

Patient Statistics October 1, 2015 through September 30, 2016, provided by Partners HealthCare Business Planning

Currently forming to comply with Joint Commission policy,31 with members including Infectious Diseases, pharmacy, infection preventionist, and practitioners.

Abbreviations: MGH, Massachusetts General Hospital; BWH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; NWH, Newton Wellesley Hospital; BWF, Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital; NSMC, North Shore Medical Center; ICU, Intensive Care Unit

Figure 1.

Assembling a Team

This workgroup structure displays the teams assembled at each hospital site as well as the umbrella Partners HealthCare team structure. Each hospital team required an executive sponsor, a clinical champion (Allergy/Immunology, Infectious Diseases, or Internal Medicine), pharmacy lead, and nursing lead.

Abbreviations: MGH, Massachusetts General Hospital; BWH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; BWF, Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital; NWH, Newton-Wellesley Hospital; NSMC, North Shore Medical Center

2. Developing or Selecting an Approach

Our Chosen Intervention: A Computerized Guideline

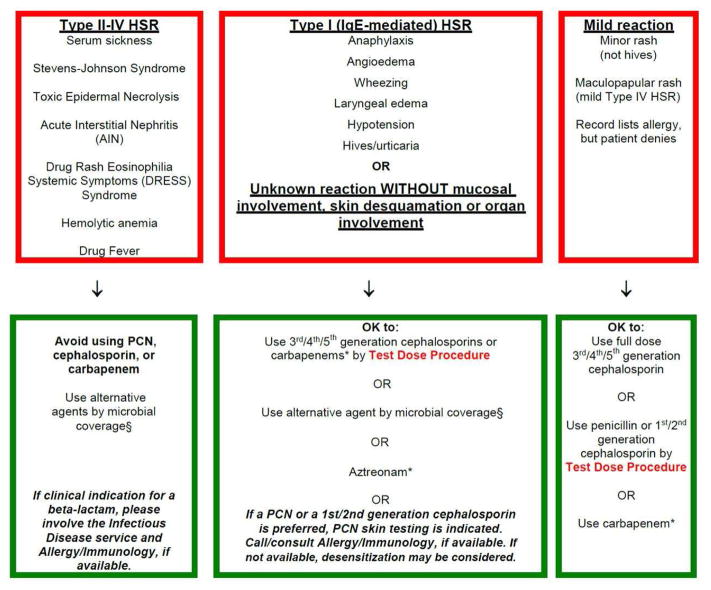

In 2013, MGH designed and implemented a pathway for general inpatient providers to care for patients with reported penicillin or cephalosporin allergies. In devising the pathway, we required standardization of the varied allergy clinical practices within our healthcare system, and creation of an approach for non-allergists that would improve antibiotic choice without compromising patient safety. The guideline we chose, therefore, increased beta-lactam use, improving quality, but was appropriately risk averse, maximizing safety. The pathway, which took the form of a printed guideline available throughout the hospital and online in the hospital policy manual, directed full dose challenges and graded challenges (i.e., test doses), for patients with low-risk allergy histories to penicillins or cephalosporins (Figure 2, EFigure 1). All guideline-recommended test doses were performed by the general medical teams on general inpatient units.34,38,39 When penicillin skin testing was necessary given the combination of allergy history and desired antibiotic, the guideline recommended allergy consultation. Skin testing to other beta-lactams (e.g., ampicillin, cephalosporins) may have been performed, when indicated, after determination by the consulting allergist.

Figure 2.

The Partners Penicillin and Cephalosporin Hypersensitivity Pathway

These pathway structures were used by the electronic decision support tool for reported hypersensitivities to penicillins and cephalosporins. Recommendations made by the computerized guideline followed these pathways.

- Type II–IV hypersensitivity reaction, avoidance of beta-lactams

- Type I IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction or unknown reaction, 3rd/4th/5th generation cephalosporins can be used by test dose directly; to use 1st/2nd generation cephalosporins or penicillins, penicillin skin testing or desensitization and Allergy/Immunology follow up was recommended.

- Mild hypersensitivity reaction including electronic health record discrepancies and benign morbilliform rashes, 3rd/4th/5th generation cephalosporins can be used by full dose and 1st/2nd generation cephalosporins and penicillins can be used by test dose.

(B) Cephalosporin hypersensitivity pathway

Abbreviations/Footnotes:

HSR, hypersensitivity reaction

* Requires Infectious Diseases approval

§ Alternative agents by microbial coverage:

Gram positive coverage: Vancomycin, linezolid*, daptomycin*, clindamycin, doxycycline, TMP/SMX

Gram negative coverage: Quinolones, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, aminoglycosides, aztreonam*

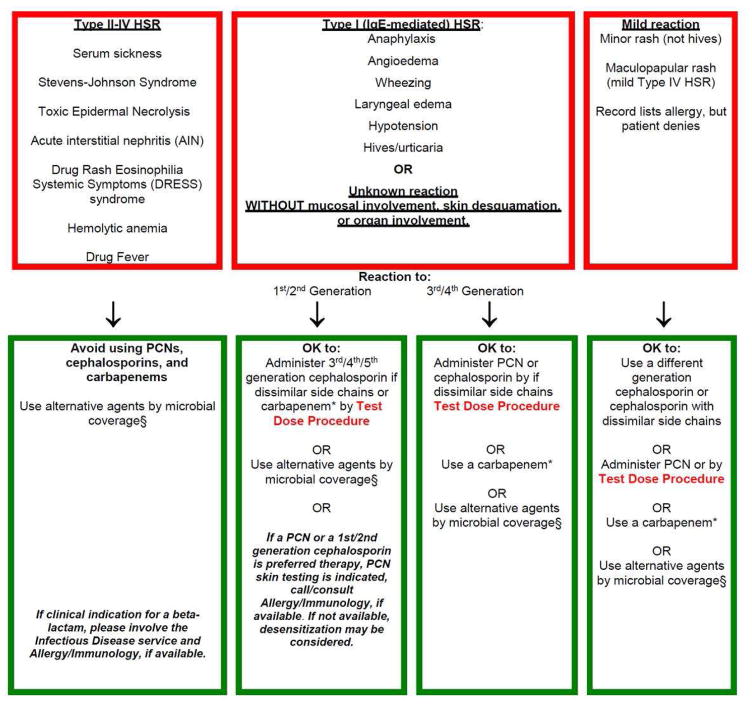

We studied the clinical guideline at MGH, and identified that it was safe, and led to switches from antibiotics like vancomycin and aztreonam to beta-lactam antibiotics.38 We demonstrated that compared to pre-guideline, post-guideline patients with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia were treated more frequently with a first-line therapy antibiotic (oxacillin, nafcillin, cefazolin).6 We subsequently computerized and modified the MGH intervention based on user feedback, expertise from BWH, and plans for a unified approach across the Partners HealthCare System. A fully electronic, mobile-friendly, and interactive guideline was created and housed on an intranet site maintained behind the Partners HealthCare firewall (Figure 3). In addition to links for the printed versions of the guideline, the website included optional clinical decision support for taking the allergy history, brief educational videos, and research/guidelines supporting penicillin allergy evaluation.14–18,38

Figure 3.

The Computerized Partners Penicillin and Cephalosporin Hypersensitivity Pathway

The computerized guideline/website contained optional clinical decision support for taking a drug allergy history. After answering questions from the patient’s allergy history, the decision support would group immunologic reactions into one of three categories described in the Partners Penicillin and Cephalosporin Hypersensitivity Pathway in Figure 2. The computerized guideline/website also included links to education videos as well as research and guidelines supporting beta-lactam allergy evaluation.

Abbreviations:

DRESS, drug rash eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; PCN, penicillin

Prior to implementation throughout the system, the website was tested and prospectively studied at BWH, with results demonstrating that patients with reported penicillin allergy in the computerized guideline period had significant, almost 2-fold, increased odds of receiving an inpatient beta-lactam antibiotic compared to the standard of care period.40 While the final computerized guideline was a single, Partners-wide document, each hospital team worked through their specific committees to obtain institutional approval. Using internal data and prior literature-based inputs,5, 41–45 we projected from 8.9 to 13.7 million dollars in one year could be saved by implementation of the computerized guideline across Partners hospitals (Table EI).

Methods for Evaluating Penicillin Allergy

Regardless of the specific policy chosen, all interventions must consider how to integrate drug allergy procedures, including penicillin skin testing, test dose challenges, and desensitization, into hospital care.

Penicillin Skin Testing

Skin testing to penicillin is usually performed by allergists or allergy registered nurses, nurse practitioners, or trainees. However, penicillin skin testing can be learned by other clinical providers, including medical doctors and nurses from other specialties.22 In some states, pharmacists can also perform penicillin skin testing.21,23

The Partners-wide guideline34,38,39 required allergist-performed skin testing for patients that needed a penicillin or early generation (1st or 2nd) cephalosporin whose allergy history was either (1) a history of reaction that is suspicious for an immunoglobulin (Ig) E mechanism or (2) an unknown reaction without warning signs of a severe cutaneous adverse reaction. Because skin testing was not readily available at two of the community hospitals, we adapted recommendations to include an option for desensitization and penicillin skin testing arranged as an outpatient on discharge. MGH, BWH, and NSMC performed penicillin skin testing on inpatients through an allergy consultation mechanism. We chose not to indiscriminately skin test inpatients because of operational barriers observed in the BWH prospective study, where, without a designated skin tester and without an imminent need to change antibiotics based on skin test results, only 25% of skin-test eligible patients completed testing.40

A pre-prepared toolbox-type kit with skin pricks, intradermal needles, alcohol swabs, measuring rulers, and permanent markers improved penicillin skin testing operations on inpatient units. A smaller, separate container with histamine, saline, and Pre-Pen was stored in the refrigerator and added to the toolbox at the time of need. MGH and BWH additionally tested with penicillin G by both epicutaneous and intradermal skin testing.46 At MGH, the mixing and diluting of penicillin G was performed by the consulting allergist, while BWH used the central pharmacy to compound and deliver the penicillin to the patient’s care unit via pneumatic tube or floor delivery. While the latter method ensured mixing was performed in a standardized fashion, it also caused operational delays since the timing of skin testing was reliant on the inpatient pharmacy workflow.

Test Dose Challenges

One of the principal and scalable methods to standardize the approach to inpatients with documented penicillin allergy is to implement graded challenges, or test doses, for low risk patients.13,38,47–50 Test doses can be used with or without prior skin testing, depending on allergy history and assessed risk.9,13,38,47–50 The aim of the test dose is to rule out IgE-mediated drug hypersensitivity; that is, test doses are for patients unlikely to be truly allergic. Test doses have been safely used in both outpatient and inpatient settings; MGH introduced non-allergist providers to beta-lactam antibiotic test doses in 2013 with the original guideline,38 and since that time has performed over 800 inpatient test doses. After successful completion of a test dose challenge (test dose and full dose), patients can safely be continued on the full dose of their antibiotic for treatment of their infection.

While simple and scalable in theory, we encountered a multitude of problems creating a safe, standardized, and efficient process for ordering, preparing, and administering parenteral test doses of beta-lactam antibiotics. Addressing these challenges, and reaching a consensus methodology, took approximately two months’ time (EFigure 2). Specific considerations for parenteral test doses include:

Number of Drug Products. There was a choice between dispensing one product with either one or two compounding labels, or two dispensed products (i.e., first product/order is the test dose and second product/order is the full dose). In this decision, we needed to consider that with one dispensed product, there is the possibility of an improper dose error (i.e., administering the full dose inadvertently), and the use of two labels on one product is not a recommended practice.51 We therefore chose to recommend two orders and two products.

Product Preparation, Dispensing, and Dosing. Drug products could be mixed and prepared in the central pharmacy and/or retrieved from automated dispensing cabinets (e.g., Omnicell®). If the test dose is not prepared from a premixed full dose, then it is important to ensure the test dose is not diluted to a concentration lower than the full dose, which could result in a false negative test dose as patients may not react due to the altered concentration.49,50 Many hospitals do not carry 25mL diluent bags, and mixing the test dose in a 50mL diluent bag results in a test dose that is about 10-fold more dilute than the full dose. With that in mind, we opted to draw up the test dose from a full dose bag into a syringe or a diluted vial for administration. A two-step intravenous challenge could be a 10% test dose followed by either a 90% dose or 100% dose. An important practical consideration in determining which option suited us best was closely aligned with product availability across all institutions. Within our system, three strategies were identified as potential options for preparing the antibiotic test doses from the full dose bags: (1) ADD-Vantage™ system, (2) MINI-BAG Plus™ system, or (3) a small volume parenteral (EFigure 3). In order to prepare the 10% test dose from the MINI-BAG Plus™ or the ADD-Vantage™ bags, the pharmacist draws the 10% dose out of the administration port. Utilizing the administration port for this purpose would subsequently necessitate a nurse attaching the administration tubing outside of a sterile environment. This practice was not ideal for maintaining sterility or adhering to regulatory requirements, therefore we chose to compound the intravenous 10% dose in the pharmacy clean room and dispense a 100% full dose that could be removed from the automated dispensing cabinets. Our choice maximized patient safety and operational efficiency; however, it resulted in drug waste (90% of one dose was discarded).

Test Dose Administration Method. Because the small volume of the test dose limited the utility of the volumetric intravenous pumps, we opted to have the test dose administered by slow intravenous push over 5 minutes (usually about 1mL per minute). In choosing this administration method, hospitals needed to create, or amend, their nursing intravenous push policy.

Observation Time. The observation time and requirements by nursing varied from institution to institution based on the local policy, perceived comfort, and hospital resources. MGH chose a period of observation between test dose and full dose of 60 minutes; BWH chose to observe 30 minutes prior to the full dose. All hospitals required a one to one nursing assignment for the duration of the challenge, but did not require the nurse to be present at the bedside for the duration of the procedure. NSMC, however, advised nurses to remain at the bedside for 15 minutes after each step of the protocol. Finally, some hospitals chose to place general restrictions on when test dose challenges would be performed. For example, recommending that challenges occur during daytime shifts and weekdays, when possible.

Standardization of oral beta-lactam test doses did not require similar effort, and we largely decided to mirror the choices made for parenteral test doses for standardized labeling, dosing, and observation time.

Desensitization

Desensitization (i.e., induction of tolerance) protocols were standardized prior to this initiative, and no changes were made to the process by which desensitizations were ordered or performed. Most sites perform antibiotic desensitization in the intensive care unit setting (Table I). However, in implementing this new policy for beta-lactams, all hospital policies for test doses were separated from hospital policies of desensitization, largely to clarify that these processes are intrinsically different. We emphasized that desensitization was reserved for the allergic, or presumed allergic, patients.

Updating the Allergy List

It was important to ensure that changes to allergies were updated in the electronic health record (EHR) and communicated properly to the patient, as well as the patient’s medical providers. For patients who received negative skin testing or test dose challenges to the same drug for which they have the reported allergy, the allergy can be deleted. However, a prior study identified that 1 in 5 parents of children who had a history of penicillin allergy, but negative penicillin allergy evaluation, still did not give their children penicillins because of fear of an allergic reaction.52 Another study identified that 36% of patients with a history of penicillin allergy and negative penicillin allergy evaluation, had penicillin allergy redocumented without reason.53 These data highlight the importance of proper communication and education for patients and providers.

3. Spreading the Change: Electronic Health Record Integration and Education

We used two primary methods for spreading the intervention: computerized support through the EHR and a traditional, multi-pronged education campaign.

EHR Integration

Best Practice Advisory (BPA)

Integration into the EHR is crucial for guidelines to have sufficient uptake.54 We targeted integration at the point of need (i.e., when an inpatient with penicillin allergy is prescribed an antibiotic) through a BPA (EFigure 4). Specifically, the BPA directed providers to our website/guideline when they placed an order for a targeted antibiotic (e.g., aztreonam) in a patient with reported penicillin or cephalosporin allergy. The BPA also contained hyperlinks to the computerized guideline and the allergy section of the EHR. In choosing to implement a BPA, the desire of our team for 100% uptake was balanced by the wants of our providers and healthcare system to limit inconsequential interruptive alerts that can negatively impact patient safety.55,56 Additionally, we balanced distinct antibiotic stewardship priorities. For example, while one site requested the BPA to fire for all fluoroquinolones, another site identified that this would result in over alerting in circumstances where a fluoroquinolone was an appropriate therapy.

Order Set

Creation of an EHR order set for test doses provided a safe mechanism for test dose ordering, and simultaneously standardized the preparation and administration instructions (See Product Preparation, Dispensing, and Dosing and Test Dose Administration Method). The order set contained a hyperlink to the computerized guideline. The test dose order set automatically defaulted for the most commonly used adult antibiotic doses, and not only calculated the test dose, but included as needed orders for diphenhydramine and epinephrine (EFigure 5). Medication formulary differences between the five hospitals, including vial sizes and preparation practices, were considered, and only locally-available beta-lactams were shown to the provider by using the admitting location of the patient.

Educational Campaign

Our initial MGH educational intervention in 2013 included 10-minute educational presentations delivered to 15 targeted groups of inpatient providers throughout the hospital.34,38 High impact groups included internal medicine, hematology/oncology, infectious diseases, transplantation, general surgery, pediatrics, pulmonary/cystic fibrosis, and pharmacy. The analysis at one year suggested that internal medicine and surgery services were the most common guideline users.39

For system-wide expansion, we first asked each hospital team to identify the educational needs of their respective institution, and high impact groups. At a minimum, the educational initiative at each hospital consisted of: (1) training the hospital team leaders and pharmacists; (2) email instructions to all clinical providers that announced and explained the initiative and included links to the website, links to the educational videos (EFigure 6),57 and PDFs of the posters/pocket cards (EFigure 7); and (3) posters hung in high traffic clinician work rooms and pocket cards delivered to inpatient providers in the hospital. The educational videos included four videos intended for healthcare providers and one video intended for patients. Patients additionally received standardized written information as part of the patient consent process for test doses at BWH, BWF, and NSMC. In-person educational sessions for providers were offered to high impact groups, and varied both in formality, from grand rounds to workshops, and duration, from 10 to 60 minutes. The educational program covered the impact of unverified penicillin allergies, the Partners computerized guideline and EHR enhancements, communicating with patients, and updating the allergy list. The educational initiative was modifiable based on hospital needs. Sites that needed more education have opted for more in-person educational sessions and/or made the educational videos mandatory learning.

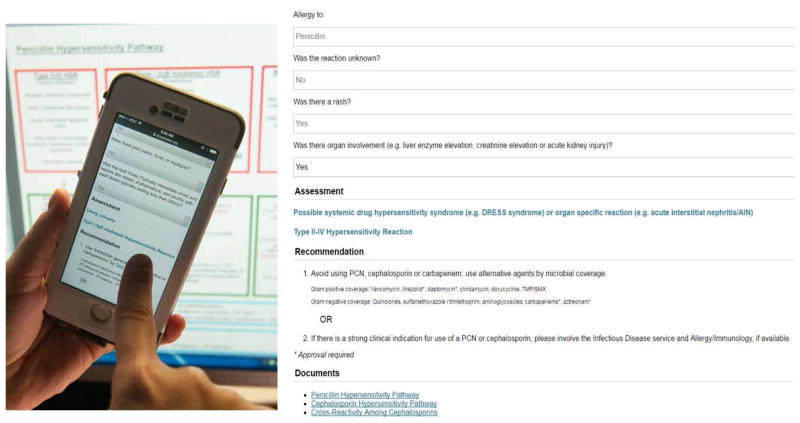

4. Establishing Measures and Testing Changes: Monitoring Uptake and Impact

Improvement interventions benefit from evaluation and subsequent refinement of the intervention and/or spread plan through Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles.27 To improve patient clinical outcomes, as well as provider uptake and usability, we monitor our intervention through a variety of methods and measures. First, we assess process measures, including website usage (number of providers, provider types, patient types, users completing decision support), website traffic (webpage views, time on website, new and returning users), and BPA firing. We additionally follow outcome measures, including test dose orders received through the EHR’s reporting function and resultant adverse drug reactions. We are still identifying the best method to track relevant changes to the EHR allergy list. From the available data, we devised a single monthly reporting dashboard that included key data for ongoing assessment and monitoring (Figure 4). Each hospital reviews internal data monthly, and determines how best to adapt implementation. Monthly conference calls between sites allow for sharing of ideas, challenges, and best practices.

Figure 4.

Monthly Dashboard for Monitoring Implementation and Impact

This monthly dashboard uses data from various sources (website, Google analytics, EHR reporting) to enable evaluation of the intervention use and uptake.

Abbreviations: MGH, Massachusetts General Hospital; BWH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; BWF, Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital; NWH, Newton-Wellesley Hospital; NSMC, North Shore Medical Center; EHR, electronic health record

CONCLUSIONS

We designed and implemented a computerized guideline for inpatients with a reported penicillin or cephalosporin allergy as a healthcare system-wide quality improvement initiative across five hospitals in the Boston area. In doing so, we identified barriers to implementation impacting the efficacy, safety, efficiency, cost, and uptake of the intervention. Many of the issues that arose were due to differences in existing processes used in inpatient practice, such as safety practices for medication labels and the use of the automated dispensing cabinets for distribution of many beta-lactam antibiotics on the inpatient units. Ultimately, we identified a safe, scalable method for performing intravenous test doses, although we were disappointed this method included drug waste. However, one dose of beta-lactam drug waste costs from $0.43 a dose (amoxicillin) to $46.16 a dose (cefotetan).37 We projected a possible 8.9 to 13.7 million dollars savings in the first year, a cost savings which far exceeds implementation and program costs. We were able to encourage providers to adopt the intervention with an easy-to-use computerized guideline and incorporating a BPA and a test dose order set with hyperlinks in the EHR. We designed free, online videos for clinical champions to use for educating providers at locations without immediate access to Allergy/Immunology, but additionally used traditional methods of education, such as presentations and pocket cards. We monitor our progress using both process and outcome measures derived from EHR data sources. As the policy continues to spread, we believe this intervention will increase education and awareness of drug allergies throughout our healthcare system, and improve both patient safety and antibiotic choice among those with prior beta-lactam allergies.

Addressing unverified beta-lactam allergies is an area that is important to healthcare today, and allergists have much to offer. The lessons learned from our experience in implementation in a healthcare system with varied institutional resources are widely applicable across a range of settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the Partners Penicillin and Cephalosporin Hypersensitivity Pathway Team, including Sharon Keogh, MSN, RN, PCCN (NWH), Erin P. Kelleher, RN (BWH), Christine M. Smith, RN (BWH), Suzelle Saint-Eloi, RN, MS (BWF), and Diane N. Menasco, RN (NSMC). The authors thank hospital-specific executive sponsors Elizabeth Mort, MD, MPH (MGH), Brian M. Cummings, MD (MGH), Karl Laskowski, MD, MBA (BWH), Jessica Dudley, MD (BWH), Janet Jodi Larson, MD (NWH), Margaret M. Duggan, MD (BWF), and Mitchell S. Rein, MD (NSMC), and our overall Partners executive sponsor, Thomas Sequist, MD (BWH, PHS). The authors thank the MGH Penicillin and Cephalosporin Hypersensitivity Pathway team members, David C. Hooper, MD, Aleena Banerji, MD, and Christy A. Varughese, PharmD. We would also like to thank Orinta Kalibatas for her project management support, Brett A. Macaulay for programming support, Joshua Touster Photography, and Massachusetts College of Pharmacy & Health Sciences student Michael Roy. Finally, authors thank Ali Bahadori, MD and Shirley Xiang Fei, PharmD from Partners eCare for their work integrating our work into the EHR.

FUNDING

This work was supported by Partners HealthCare Quality, Safety and Value and the Clinical Process Improvement Leadership Program. Dr. Blumenthal is supported by NIH K01AI125631-01 and the American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health nor the AAAAI.

Abbreviations

- ASCs

Antibiotic Stewardship Committees

- MGH

Massachusetts General Hospital

- BWH

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

- BWF

Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital

- NWH

Newton Wellesley Hospital

- NSMC

North Shore Medical Center

- Ig

Immunoglobulin

- EHR

Electronic Health Record

- BPA

Best Practice Alert

- HSR

hypersensitivity reaction

- DRESS

Drug rash eosinophilia and systemic symptoms

- PCN

penicillin

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Blumenthal KG, Parker RA, Shenoy ES, Walensky RP. Improving clinical outcomes in patients with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and reported penicillin allergy. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(5):741–749. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee CE, Zembower TR, Fotis MA, Postelnick MJ, Greenberger PA, Peterson LR, et al. The incidence of antimicrobial allergies in hospitalized patients: implication regarding prescribing patters and emerging bacterial resistance. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(18):2819–2822. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.18.2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Picard M, Begin P, Bouchard H, Cloutier J, Lacombe-Barrios J, Paradis J, et al. Treatment of patients with a history of penicillin allergy in a large tertiary care academic hospital. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(3):252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeffres MN, Narayanan PP, Shuster JE, Schramm GE. Consequences of avoiding beta-lactams in patients with beta-lactam allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(4):1148–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacFadden DR, LaDelfa A, Leen J, Gold WL, Daneman N, Weber E, et al. Impact of Reported Beta-Lactam Allergy in Inpatient Outcomes: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(7):904–910. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Huang M, Kuhlen JL, Ware WA, Parker RA, et al. The impact of reporting a prior penicillin allergy on the treatment of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. PloS One. 2016;11(7):e0159406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: A cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):790–796. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macy E, Ngor EW. Safely diagnosing clinically significant penicillin allergy using only penicilloyl-poly-lysine, penicillin, and oral amoxicillin. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(3):258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bourke J, Pavlos R, James I, Phillips E. Improving the effectiveness of penicillin allergy de-labeling. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(3):365–374. e361. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rimawi RH, Cook PP, Gooch M, Kabchi B, Ashraf MS, Rimawi BH, et al. The impact of penicillin skin testing on clinical practice and antimicrobial stewardship. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):341–345. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King EA, Challa S, Curtin P, Bielory L. Penicillin skin testing in hospitalized patients with beta-lactam allergies: Effect on antibiotic selection and cost. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117(1):67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arroliga ME, Radojicic C, Gordon SM, Popovich MJ, Bashour CA, Melton AL, et al. A prospective observational study of the effect of penicillin skin testing on antibiotic use in the intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24(5):347–350. doi: 10.1086/502212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mill C, Primeau MN, Medoff E, Lejtenyi C, O’Keefe A, Netchiporouk E, et al. Assessing the Diagnostic Properties of a Graded Oral Provocation Challenge for the Diagnosis of Immediate and Nonimmediate Reactions to Amoxicillin in Children. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(6):e160033. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Is it Really a Penicillin Allergy? [Internet] 2016 [cited 2017 Jan 19]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/week/downloads/getsmart-penicillin-factsheet.pdf.

- 15.National Quality Forum. NQF launches antibiotic stewardship initiative [Internet] 2015 Oct 16; [cited 2017 Jan 19]. Available from: http://www.qualityforum.org/News_And_Resources/Press_Releases/2015/NQF_Launches_Antibiotic_Stewardship_Initiative.aspx.

- 16.Choosing Wisely. Five things physicians and patients should question [Internet] 2016 [cited 2017 Jan 19]. Available from: http://www.choosingwisely.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Choosing-Wisely-Recommendations.pdf.

- 17.Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, MacDougall C, Schuetz AN, Septimus EJ, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):e51–77. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Academy Of Allergy Athma and Immunology. Position Statement: Penicillin Allergy [Internet] 2016 Sep; [cited 2017 Jan 17]. Available from: http://www.aaaai.org/Aaaai/media/MediaLibrary/PDF%20Documents/Practice%20and%20Parameters/AAAAI-PAAR-position-statement-9-16.pdf.

- 19.Arroliga ME, Vazquez-Sandoval A, Dvoracek J, Arroliga AC. Penicillin skin testing is a safe method to guide beta-lactam administration in the intensive care unit. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;116(1):86–87. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arroliga ME, Wagner W, MBB, Hoffman-Hogg L, Gordon SM, Arroliga AC. A pilot study of penicillin skin testing in patients with a history of penicillin allergy admitted to the medical ICU. Chest. 2000;118(4):1106–1108. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.4.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wall GC, Peters L, Leaders CB, Wille JA. Pharmacist-managed service providing penicillin allergy skin tests. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(12):1271–1275. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.12.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heil EL, Bork JT, Schmaizie SA, Kleinberg M, Kewalramani A, Gilliam BL, et al. Implementation of an infectious disease fellow managed penicillin allergy skin testing service. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(3) doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw155.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen JR, Tarver SA, Alvarez KS, Tran T, Khan DA. A Proactive Approach to Penicillin Allergy Testing in Hospitalized Patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ressner RA, Gada SM, Banks TA. Antimicrobial stewardship and the allergist: reclaiming our antibiotic armamentarium. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(3):400–401. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swearingen SM, White C, Weidert S, Hinds M, Narro JP, Guarascio AJ. A multidimensional antimicrobial stewardship intervention targeting aztreonam use in patients with a reported penicillin allergy. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(2):213–217. doi: 10.1007/s11096-016-0248-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trimble C. How Physicians Can Fix Health Care: One Innovation at a Time. Tampa (FL): American Association for Physician Leadership; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langley GL, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, CLN, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. 2. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKibben L, Horan T, Tokars JI, Fowler G, Cardo DM, Pearson ML, et al. Guidance on public reporting of healthcare-associated infections: recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control. 2005;33(4):217–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott RD. The Direct Medical Costs of Healthcare-Associated Infections in the U.S. Hospitals and the Benefits of Prevention. Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [cited 2017 Jan 18]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/HAI/pdfs/hai/Scott_CostPaper.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stone PW, Glied SA, McNair PD, Matthes N, Cohen B, Landers TF, et al. CMS changes in reimbursement for HAIs: setting a research agenda. Med Care. 2010;48(5):433–439. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d5fb3f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joint Commission on Hospital Accreditation. Approved: New antimicrobial stewardship standard. Jt Comm Perspect. 2016;36(7):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sturm JM, Temprano J. A survey of physician practice and knowledge of drug allergy at a university medical center. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(4):461–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stukus DR, Green T, Montandon SV, Wada KJ. Deficits in allergy knowledge among physicians at academic medical centers. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(1):51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Hurwitz S, Varughese CA, Hooper DC, Banerji A. Effect of a drug allergy educational program and antibiotic prescribing guideline on inpatient clinical providers’ antibiotic prescribing knowledge. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(4):407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, MacDougall C, Schuetz AN, Septimus EJ, et al. Executive Summary: Implementing an Antibiotic Stewardship Program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):1197–1202. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, Infectious Diseases Society of America, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. Policy statement on antimicrobial stewardship by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(4):322–327. doi: 10.1086/665010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Micromedex Solutions [Internet] Truven Health Analytics. c2016 [cited 2017 Jan 17]. Available from: micromedex.com.

- 38.Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Varughese CA, Hurwitz S, Hooper DC, Banerji A. Impact of a clinical guideline for prescribing antibiotics to inpatients reporting penicillin or cephalosporin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(4):294–300. e292. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Solensky R. A novel approach to improving antibiotic selection in patients reporting penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(4):257–258. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blumenthal KG, Wickner PG, Hurwitz S, Pricco N, Nee AE, Laskowski K, et al. Tackling Inpatient Penicillin Allergies: Tools for Antimicrobial Stewardship. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.02.005. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou L, Dhopeshwarkar N, Blumenthal KG, Goss F, Topaz M, Slight SP, et al. Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy. 2016;71(9):1305–1313. doi: 10.1111/all.12881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pakyz AL, MacDougall C, Oinonen M, Polk RE. Trends in antibacterial use in US academic health centers: 2002 to 2006. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(20):2254–2260. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.20.2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bates DW, Spell N, Cullen DJ, Burdick E, Laird N, Petersen LA, et al. The costs of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Adverse Drug Events Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1997;277(4):307–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Classen DC, Pestotnik SL, Evans RS, Lloyd JF, Burke JP. Adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA. 1997;277(4):301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barrett ML, Wier LM, Jiang J, Steiner CA. Statistical brief #199. All-cause readmissions by payer and age, 2009–2013. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2015 Dec; [cited 2017 Jan 21]. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb199-Readmissions-Payer-Age.jsp.

- 46.Fox S, Park MA. Penicillin skin testing in the evaluation and management of penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;106(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iammatteo M, Blumenthal KG, Saff R, Long AA, Banerji A. Safety and outcomes of test doses for the evaluation of adverse drug reactions: A 5-year retrospective review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(6):768–774. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kao L, Rajan J, Roy L, Kavosh E, Khan DA. Adverse reactions during drug challenges: a single US institution’s experience. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;110(2):86–91. e81. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khan DA, Solensky R. Drug allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 Suppl 2):S126–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Solensky R, Khan D. Drug allergy: An updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(4):259–273. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.ASHP guidelines on preventing medication errors in hospitals. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1993;50(2):305–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Picard M, Paradis L, Nguyen M, Begin P, Paradis J, Des Roches A. Outpatient penicillin use after negative skin testing and drug challenge in a pediatric population. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012;33(2):160–164. doi: 10.2500/aap.2012.33.3510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rimawi RH, Shah KB, Cook PP. Risk of redocumenting penicillin allergy in a cohort of patients with negative penicillin skin tests. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):615–618. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bates DW, Kuperman GJ, Wang S, Gandhi T, Kittler A, Volk L, et al. Ten commandments for effective clinical decision support: Making the practice of evidence-based medicine a reality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(6):523–530. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Topaz M, Seger DL, Lai K, Wickner PG, Goss FR, Dhopeshwarkar N, et al. High Override Rate for Opioid Drug-allergy Interaction Alerts: Current Trends and Recommendations for Future. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:242–246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Topaz M, Seger DL, Slight SP, Goss F, Lai K, Wickner PG, et al. Rising drug allergy alert overrides in electronic health records: An observational retrospective study of a decade of experience. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015 doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blumenthal KG. Drug Allergy Vidscripts [Educational Videos] 2016 [cited 2017 Jan 17]. Available from: https://app.vidscrip.com/vidscrip/5726cb7ca254a5897c3c722e. https://app.vidscrip.com/vidscrip/5726cb7ca254a5897c3c722d. https://app.vidscrip.com/vidscrip/5726cb7ca254a5897c3c720d https://app.vidscrip.com/vidscrip/5726cb7ca254a5897c3c7228. https://app.vidscrip.com/vidscrip/5726cb83a254a5897c3c7902.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.