Abstract

Background

It is known that parents have lower mortality than childless individuals. Support from adult children to ageing parents may be of importance for parental health and longevity. The aim of this study was to estimate the association between having a child and the risk of death, and to examine whether the association increased at older ages when health starts to deteriorate and the need of support from a family member increases.

Methods

In this nationwide study, all men and women (born between 1911 and 1925 and residing in Sweden), as well as their children, were identified in population registers and followed over time. Age-specific death risks were calculated for each calendar year for individuals having at least one child and for individuals without children. Adjusted risk differences and risk ratios were estimated.

Results

Men and women having at least one child experienced lower death risks than childless men and women. At 60 years of age, the difference in life expectancy was 2 years for men and 1.5 years for women. The absolute differences in death risks increased with parents' age and were somewhat larger for men than for women. The association persisted when the potential confounding effect of having a partner was taken into account. The gender of the child did not matter for the association between parenthood and mortality.

Conclusions

Having children is associated with increased longevity, particularly in an absolute sense in old age. That the association increased with parents' age and was somewhat stronger for the non-married may suggest that social support is a possible explanation.

Keywords: AGEING, Life course epidemiology, LONGITUDINAL STUDIES

Introduction

It is well established that parents live longer than non-parents,1–4 but the underlying mechanisms are unclear and it is not known how the association changes over the life course. In Sweden and the other Nordic countries,5 there is an overall trend of increasing levels of childlessness across birth cohorts. It may therefore be valuable to improve our understanding of how childlessness is linked to health and survival chances in old age. In the latest decades in Sweden, there has also been a shift from older people living in institutions to living at home with assistance, and the proportion of elderly people in Sweden that receives care from their children or other close persons has increased.6 7 Therefore, to further investigate health and survival consequences for childless older individuals is of importance. We hypothesise that support from adult children to their ageing parents may be of importance for parental health and longevity. However, there are of course several alternative explanations. For example, the timing and number of children could affect the mortality risk of women through biological pathways, particularly in organs that are sensitive to hormonal stimuli such as breast, uterus and ovary.8 9 Still, a protective effect of parenthood has been found for mothers and fathers,3 4 10 which may suggest that the biological mechanisms that apply to women is not the only explanation to the association, and other factors matter as well. One such factor could be various types of support from adult children to their ageing parents,4 such as informational, emotional and social support. In addition, parents have on average more healthful behaviours than childless individuals.11 It is also possible that the survival advantage of parents over non-parents is due to confounding from biological or social factors influencing the chances of having children and the risk of death. Health-related selection may be important at any phase during the life course, but it seems reasonable that the influence would not increase when parents become very old, but rather being more significant before average life expectancy (LE) as frailer individuals tend to die off. The need for social support from family members may, on the other hand, increase when parents age because ill health becomes more common with increasing age and the ability of self-care may decrease.

How the mortality advantage of parents over non-parents changes over the life span, is not known. Previous studies have mainly examined associations between parity and subsequent mortality from 40 years of age up to around 60 years of age,1 3 8 9 and a few studies have investigated the association in older ages.2 4 12 Only in two of these studies, the association between having children and parental mortality was presented over age, and was shown to be strongest at the age of 60 and thereafter decrease.2 12 However, the association was measured as relative risks. If the aim is to explore whether the presence of children is more important in older ages than in younger ages, we believe that absolute risk differences are more informative. This is because death risk increases with age and the effect of children on parental mortality (among all other risk factors) is relatively small, and thus, the risk ratios will consequently decrease with age even if the absolute effect of children on mortality increases.

At old age, the stress of parenthood is likely to be lower and instead, parents can benefit from social support from their children. Such support has in earlier research indicated health advantages.13–15 It has also been shown that childless older individuals receive less social support than parents do: In a review, one of the major findings was that old childless people who were in poor health and lived alone faced potential support deficits.16

Related to the hypothesis of a greater need of social support in old age and the help from children for such needs, is the role of the gender of the child for parental mortality. Having a daughter has been shown to be associated with increased chances of regular social contact and with receiving help if needed,16 17 something that we hypothesise becomes more important later in life. The role of daughters versus sons for parental mortality has been the topic of a few previous studies, but the results are inconsistent. Some studies found no association with the gender of the child,18 19 while other found that daughters are more favourable,20 sometimes for fathers only.13 In a study on Swedish data, the protective effect of having a daughter was detected only among one-child parents, but not for parents with several children,14 which is in line with a Norwegian study.15 However, none of these studies followed individuals into ages above average LE.

This study closely examines the association between parenthood and longevity, with specific focus on the strength of the association in old age, and with absolute and relative measures. More specifically, we investigate; (1) the association between having a child alive in old age and the risks of death among Swedish men and women, (2) whether the association increases with age of the parent and (3) whether the association persists when stratifying for marital status (taking into account the possible confounding effect of having a partner cohabiting). We further conduct sensitivity analyses in order to increase the insight of the possible explanations to the survival advantage of parents over non-parents: whether the association differed by gender of the child, how the educational level affects the association and if geographical distance between parent and child interacts with the relationship between having children and mortality in old age.

Methods

Sweden, together with the other Nordic countries, has a system of population-based registers where individual-level data can be linked through personal identity numbers, that is, a unique identifier assigned to all persons registered in Sweden. First, we used the Register of the Total Population (TPR) to identify all men and women born between 1911 and 1925 and residing in Sweden from the age of 60 or earlier (index persons). Second, the children of these index persons were identified in the Multigeneration Register, which includes children of parents born 1932 and onwards.21 This means that, for the first birth cohorts, any children born before the parents were 21 years of age may be missed. However, as children born later are included, and the majority of parents give birth after the age of 21, we consider this a minor problem not likely to considerably affect our results. Third, to the index persons, we added information on educational level from the Population and Housing Censuses in 1970, which was available for 96.5% of the individuals. Further, annual information on marital status was collected from the TPR. Finally, we added date of death from the Cause of Death Register (1971–2014), which includes all deaths occurring within and outside Sweden for individuals registered in Sweden.

The index persons were followed from the calendar year of their 60th birthday to death, emigration or end of follow-up (31 December 2014), whichever came first. This means that individuals were between 89 and 103 years of age at the end of follow-up.

Marital status and children were treated as time-varying covariates. Information on if the individual had a child that was alive and living in Sweden was based on whether the child was registered in the TPR 1st of January each year, or not. Thus, the definition of the presence of children was equal to having at least one child residing in Sweden (based on the hypothesis of social support). Marital status was defined as married or not married the 31st of December each year. The category of not married included never married, divorced or widowed individuals. These subcategories were collapsed based on the hypothesis that all of them signify lack of support from a cohabiting partner, and, in addition, because the small numbers made it difficult to analyse them as three separate groups. Educational level (basic, upper secondary or tertiary) was regarded as a fixed constant as all individuals were between 45 and 59 years in 1970 when information on education was collected, and it seems likely that the vast majority of the persons had reached their final educational level in that age. Adjustments were further made for geographical region and for urban versus rural region.

To investigate whether the gender of the child had any impact on the effect on parental mortality, subgroup analysis was performed for parents with one girl or one boy only. This was done in order not to confound any gender comparison with parity.

To investigate how any association between having children and mortality in old age varied with geographical distance between parents and children, we used information on where the children and parents lived on an annual basis during the follow-up period. We compared the effect of having children versus not having children on parental mortality for those parents who lived closer than 50 km from their child (or any of their children) versus parents who lived at least 50 km away from the (closest residing) child.

One year age-specific and gender-specific death risks were calculated by dividing the number of deaths during 1 year by the number of individuals alive at the beginning of that year. Even though absolute risk differences were our primary interest, we also computed risk ratios to highlight the relation between these measures and to simplify comparisons with previous studies. Death risks, death risk differences and death risk ratios were all estimated with a generalised linear model using a binomial distribution with the number of deaths as the dependent variable and person-years under risk as the number of exposed for each covariate pattern. A log-link was used to estimate the death risks and risk ratios and an identity link to estimate the risk differences. All modelled estimates were smoothed with restricted cubic splines. Four knots were used to model age and three knots were used to model the age-dependent effect of having/not having children and age. Educational level and marital status were entered into the respective models as categorical variables. Finally, the remaining life expectancies at age 60 and age 80 were estimated for men and women with and without children using smoothed death risks up to the age of 100. All analyses were done independently for men and women.

The analyses were done using the statistical software STATA V.13.1 (College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

We identified 704 481 men and 725 290 women born between 1911 and 1925, living in Sweden at the age of 60. The total person-time was 14.1 million years for men and 17.6 million years for women. The vast majority of men and women had no more than basic education, were married and had at least one child, see table 1.

Table 1.

Number of persons at age 60 and number of person-years under risk by educational levels, number of children and marital status

| Males |

Females |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At age 60 | Per cent | Person-years | Per cent | At age 60 | Per cent | Person-years | Per cent | |

| Number of persons | 704 481 | 100.0 | 14 082 357 | 100.0 | 725 290 | 100.0 | 17 578 947 | 100.0 |

| Education | ||||||||

| Basic | 490 249 | 69.6 | 9 603 412 | 68.2 | 569 857 | 78.6 | 13 669 848 | 77.8 |

| Upper secondary | 167 791 | 23.8 | 3 460 388 | 24.6 | 125 287 | 17.3 | 3 124 842 | 17.8 |

| Tertiary | 46 441 | 6.6 | 1 018 557 | 7.2 | 30 146 | 4.2 | 784 257 | 4.5 |

| Number of children | ||||||||

| 0 | 174 122 | 24.7 | 3 290 229 | 23.4 | 153 086 | 21.1 | 3 640 708 | 20.7 |

| 1 | 154 123 | 21.9 | 3 168 705 | 22.5 | 171 603 | 23.7 | 4 283 297 | 24.4 |

| 2 | 199 250 | 28.3 | 4 110 706 | 29.2 | 209 493 | 28.9 | 5 153 874 | 29.3 |

| 3+ | 176 986 | 25.1 | 3 512 717 | 24.9 | 191 108 | 26.3 | 4 501 068 | 25.6 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 551 682 | 78.3 | 9 993 139 | 71.0 | 518 849 | 71.5 | 8 163 926 | 46.4 |

| Unmarried | 152 799 | 21.7 | 4 089 218 | 29.0 | 206 441 | 28.5 | 9 415 021 | 53.6 |

| Males | With children | Without children | ||||||

| Number of persons | 530 359 | 100.0 | 10 792 128 | 100.0 | 174 122 | 100.0 | 3 290 229 | 100.0 |

| Education | ||||||||

| Basic | 356 716 | 67.3 | 7 127 783 | 66.0 | 133 533 | 76.7 | 2 475 629 | 75.2 |

| Upper secondary | 133 969 | 25.3 | 2 789 975 | 25.9 | 33 822 | 19.4 | 670 413 | 20.4 |

| Tertiary | 39 674 | 7.5 | 874 370 | 8.1 | 6767 | 3.9 | 144 187 | 4.4 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 469.317 | 88.5 | 8 568 001 | 79.4 | 82 365 | 47.3 | 1 425 138 | 43.3 |

| Unmarried | 61.042 | 11.5 | 2 224 127 | 20.6 | 91 757 | 52.7 | 1 865 091 | 56.7 |

| Females | With children | Without children | ||||||

| Number of persons | 572 204 | 100.0 | 13 938 239 | 100.0 | 153 086 | 100.0 | 3 640 708 | 100.0 |

| Education | ||||||||

| Basic | 461 147 | 80.6 | 11 131 049 | 79.9 | 108 710 | 71.0 | 2 538 799 | 69.7 |

| Upper secondary | 91 614 | 16.0 | 2 296 624 | 16.5 | 33 673 | 22.0 | 828 218 | 22.7 |

| Tertiary | 19 443 | 3.4 | 510 566 | 3.7 | 10 703 | 7.0 | 273 691 | 7.5 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 440 125 | 76.9 | 6 942 173 | 49.8 | 78 724 | 51.4 | 1 221 753 | 33.6 |

| Unmarried | 132 079 | 23.1 | 6 996 066 | 50.2 | 74 362 | 48.6 | 2 418 955 | 66.4 |

Figure 1 presents death risks by age for men and women with at least one child versus no children. The death risks increased with age in a similar trajectory for both groups and for men and women, although men had higher absolute risks of death as compared with women. For men and women, the death risks were lower among individuals with a child as compared with childless individuals, but more so for men than for women.

Figure 1.

Estimated death risks for men and women, with and without children, respectively. The estimates were smoothed with restricted cubic splines for age and the age-dependent effect of having/not having children. Observed death risks are provided as comparison.

Figure 2 demonstrates death risk differences and risk ratios by age for individuals with and without children, respectively, adjusted for educational level (dots are unadjusted estimates and smoothed lines adjusted). The differences in death risk increased with age for men and women. The risk ratios, on the other hand, decreased with age. The relative risks between having a child and having no children decreased from around 1.4 among 60-year-olds to below 1.1 at the age of 95. Table 2 shows the death risk differences adjusted for educational level and marital status, and the estimates for 60-year-old men were 0.06% (95% CI 0.02 to 0.10) and for women 0.16% (95% CI 0.13 to 0.19). The corresponding figures for 90-year-olds were 1.47% (95% CI 1.35 to 1.60) for men and 1.10% (95% CI 0.99 to 1.22) for women. Additional adjustments were made for geographical region and for urban/rural area, but none of these variables had any effect on the associations.

Figure 2.

Estimated death risk difference and death risk ratios with 95% CI for men and women, with and without children, respectively. The estimates were smoothed with restricted cubic splines for age and the age-dependent effect of having/not having children and additionally adjusted for parental educational level. Observed death risks difference and death risk ratios are provided as comparison.

Table 2.

Number of individuals at risk, number of deaths and death risk* in per cent (DR) for individuals with and without children, respectively

| Without children |

With children |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Population | Deaths | DR (95% CI) | Population | Deaths | DR (95% CI) | RD (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) |

| Males | ||||||||

| 60 | 174 122 | 2800 | 1.41 (1.37 to 1.44) | 530 359 | 6318 | 1.35 (1.32 to 1.37) | 0.06 (0.02 to 0.10) | 1.24 (1.21 to 1.27) |

| 65 | 157 757 | 3925 | 2.39 (2.37 to 2.42) | 491 374 | 9377 | 2.21 (2.19 to 2.23) | 0.18 (0.16 to 0.21) | 1.19 (1.18 to 1.21) |

| 70 | 136 137 | 4969 | 3.26 (3.23 to 3.29) | 436 264 | 12 595 | 2.89 (2.87 to 2.91) | 0.37 (0.34 to 0.41) | 1.16 (1.15 to 1.17) |

| 75 | 109 815 | 6084 | 4.91 (4.88 to 4.95) | 365 256 | 16 222 | 4.29 (4.27 to 4.31) | 0.62 (0.58 to 0.66) | 1.12 (1.11 to 1.13) |

| 80 | 79 171 | 6468 | 8.30 (8.25 to 8.35) | 277 403 | 19 115 | 7.40 (7.37 to 7.43) | 0.90 (0.84 to 0.95) | 1.09 (1.08 to 1.10) |

| 85 | 48 013 | 6014 | 12.8 (12.7 to 12.9) | 178 865 | 19 579 | 11.6 (11.6 to 11.7) | 1.19 (1.10 to 1.27) | 1.06 (1.05 to 1.07) |

| 90 | 20 096 | 3916 | 17.7 (17.6 to 17.8) | 79 377 | 14 097 | 16.2 (16.2 to 16.3) | 1.47 (1.35 to 1.60) | 1.03 (1.02 to 1.04) |

| Females | ||||||||

| 60 | 153 086 | 1299 | 0.68 (0.65 to 0.71) | 572 204 | 3442 | 0.52 (0.50 to 0.53) | 0.16 (0.13 to 0.19) | 1.35 (1.31 to 1.39) |

| 65 | 146 195 | 1862 | 1.10 (1.08 to 1.12) | 549 971 | 5220 | 0.86 (0.84 to 0.87) | 0.25 (0.23 to 0.27) | 1.30 (1.28 to 1.31) |

| 70 | 136 212 | 2588 | 1.67 (1.65 to 1.70) | 517 542 | 7655 | 1.30 (1.29 to 1.32) | 0.37 (0.34 to 0.39) | 1.25 (1.24 to 1.26) |

| 75 | 122 455 | 3695 | 2.74 (2.71 to 2.76) | 470 279 | 11 330 | 2.21 (2.19 to 2.23) | 0.53 (0.50 to 0.55) | 1.21 (1.20 to 1.22) |

| 80 | 103 066 | 5155 | 4.83 (4.79 to 4.87) | 400 570 | 17 022 | 4.12 (4.10 to 4.14) | 0.71 (0.67 to 0.75) | 1.17 (1.16 to 1.18) |

| 85 | 76 132 | 6475 | 7.88 (7.80 to 7.95) | 301 786 | 23 050 | 6.97 (6.92 to 7.02) | 0.91 (0.83 to 0.98) | 1.14 (1.13 to 1.15) |

| 90 | 41 684 | 6269 | 11.4 (11.2 to 11.5) | 165 038 | 22 765 | 10.3 (10.2 to 10.4) | 1.10 (0.99 to 1.22) | 1.11 (1.10 to 1.12) |

Risk differences* in per cent units (RD) and risk ratios* (RR) for individuals without children compared with individuals with children. Selected ages for men and women, respectively.

*Adjusted for educational level and marital status.

The remaining LE at the age of 60 for men with children was 20.2 years, whereas men without children were expected to live 18.4 years, that is, a difference of close to 2 years. The corresponding figures for women at age 60 were 24.6 and 23.1, respectively, a difference of 1.5 years. At 80 years of age, the remaining LE for men with children was 7.7 and men without children 7.0. For women, the corresponding figures were 9.5 and 8.9 years.

The analyses showed that the association between having children and mortality was found among married and unmarried but was stronger among non-married, at least for men (see figure 3). For example, for 85-year-old men, the death risk differences between men with at least one child and childless men were 1.2% among unmarried men and 0.6% among married men. The corresponding figures for women were 0.9% and 0.8%.

Figure 3.

Estimated death risks difference with 95% CI for men and women, with and without children stratified by marital status, respectively. The estimates were smoothed with restricted cubic splines for age and the age-dependent effect of having/not having children and additionally adjusted for parental educational level. Observed death risks differences are provided as comparison.

To find out whether the gender of the child had any impact on parental mortality, analyses were run investigating whether mothers and fathers with a daughter had a lower death risk than mothers and fathers with a son. The results showed no differences depending on the gender of the child (results not shown but available on request).

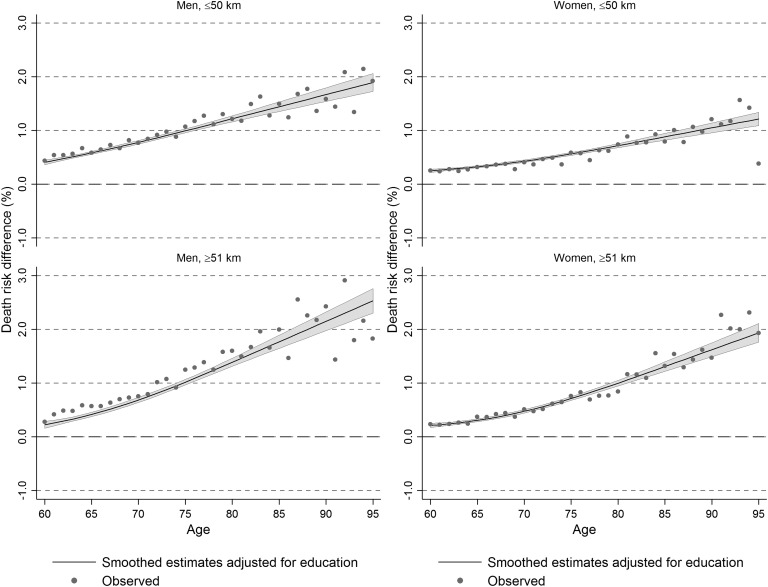

Finally, to investigate how the geographical distance between parents and their children was associated with the risk of dying, we conducted separate analyses for parents and children living more than 50 km apart and other parents (ie, <51 km), and compared these death risks to childless individuals. The results showed that the death risk differences between parents and non-parents were greater if the parents lived far away from their children, while smaller differences in death rates were found when comparing parents living close to their children and non-parents, see figure 4. This pattern was, however, clearer for women than for men.

Figure 4.

Estimated death risks differences with 95% CI for men and women, with and without children, living within 50 km from their child versus those living longer than 50 km from their child. The estimates were adjusted for parental educational level. Observed death risks differences are provided as comparison.

Discussion

This study found an inverse association between having a child and death risks in old age, and, importantly, that the death risk differences between parents and non-parents increased with age of the parent, among men and women. Further, the differences in death risks between individuals with and without children were somewhat larger for men than for women. The finding of a stronger association for men than for women is in line with a previous study where contact with children was associated with better health among parents, and more so for men than for women.22 Our finding that the association grew stronger when parents became older is further in agreement with research suggesting that childless people face support deficits only towards the end of life.16 However, selective elements and alternative explanations, for example, that parents have more healthy behaviours than non-parents,11 are not ruled out.

The association between having children and mortality persisted when stratifying for marital status, taking into account the possible confounding effect of having a partner. Thus, the presence of children is reflecting possible effects of cohabitation. The association was also stronger among the non-married than among the married, particularly among men, perhaps because the married also gain advantages of having a partner in terms of care and support, whereas the non-married and widowed would be more exclusively dependent on their adult children. Notably, the difference between the married and the non-married was clearly more pronounced among men than among women, which may relate to that marriage has sometimes been shown to be more beneficial to men's survival than to women's survival.23 Another possible explanation to the greater mortality difference among men may be that childless men are generally lower educated than men with children, whereas the opposite is true for women. Even if we control for education, the composition of childless male and female groups may differ across other socioeconomic dimensions that were not taken into consideration, and early life influences as well as later behavioural factors connected to such circumstances may affect our results.

Two of our findings may be interpreted as working against the hypothesis about the importance of social support in older ages: the lack of a stronger mortality association for parents whose children lived fairly close, and the insignificant results for the gender of the child. As for the first finding, the construction of the geographical variable was rather crude. The intention was, however, not to investigate in detail how distance affected the association, but rather to perform sensitivity analyses that could give some insights to the mechanisms. The fact that the association was stronger for those living further away from their children, however, seems contradictory to the hypothesis of social support. Our results were not adjusted for the educational level of the child (only the parent), but previous studies have shown that highly educated children are more likely to live further away from their parents24 and that parents may benefit, in terms of survival chances, of having a well-educated child,14 25 which may alter the associations found in the present study. In addition, the complete socioeconomic conditions of the individuals were not included.

As for the findings that death risks of parents did not differ depending on the gender of their child, there are known health benefits from increased social participation and the ability to draw on social support from children.22 26–28 In general, women tend to have more social ties than men, and older childless individuals, particularly men, appear to have less social interactions than older parents and there is evidence that having a daughter is associated with increased chances of regular social contacts and with receiving help if needed.16 17 We found some support for the difference between mothers and fathers, but no support for the hypothesis regarding a beneficial effect of a daughter. There are several possible explanations to this. First, gender of the child has mainly been considered in the context of social contact/support in previous research while more specific types of support may matter most for preventing mortality. In a country like Sweden, where healthcare is almost free of charge and in theory equally available for everyone, perhaps the role of support in navigating the healthcare sector, finding the right caregiver, arguing for better and/or earlier treatment, etc is of particular importance and, perhaps, daughters and sons are equally active in this type of support. Furthermore, although previous studies have shown that daughters have more regular contact with their parents than sons have, daughters-in-law may engage in their parents-in-law, and reduce any initial differences in social support between parents with a daughter and parents with a son. It may also be that the selection of one-child parents for this comparison is not representable for all families. Perhaps being the only child is related to a greater responsibility of parents, reducing the difference in the amount of help given by sons and daughters. Thus, sons may take more responsibility for their ageing parents when no other sibling is present. In addition, a previous Swedish study has found that the educational level of the parents matter for the amount of help they receive from daughters and sons, respectively. Among older well-educated individuals, there was no difference in the proportion of help received by sons or daughters, yet, among the less well educated it was more common to receive help from daughters than from sons.6 Even if our results were adjusted for education, they do not reveal the variation between educational groups. Finally, if the finding of no gender difference is not explained by any of the suggestions above, health selection rather than social support could explain the finding.

What is already known on this subject.

It is well established that parents live longer than non-parents, but the underlying mechanisms are less clear and it is further not known how the association changes over the life course, especially in old age.

What this study adds.

Parents live longer than non-parents, and this effect persists to the highest ages.

The death risk differences between parents and non-parents increased with the age of the parent but was not associated with the gender of the child.

That the association became more evident by parents' age and was somewhat stronger for the non-married may suggest that social support is one possible explanation.

Footnotes

Contributors: KM proposed the research question. MT performed the statistical analyses. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. KM drafted the first manuscript to which all authors contributed. All authors have approved the final version of this manuscript. MT had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Regional Ethics Committee, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, Dnr 2011/136-31/5 and Dnr 2015/1917-32.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data underlying this study are sensitive individual-level data protected by the personal data act. Data can only be shared after ethical approval from the Regional Ethics Committee, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, and after consent from the principal investigator.

References

- 1.Hurt LS, Ronsmans C, Thomas SL. The effect of number of births on women's mortality: systematic review of the evidence for women who have completed their childbearing. Popul Stud (Camb) 2006;60:55–71. 10.1080/00324720500436011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doblhammer G. Reproductive history and mortality later in life: a comparative study of England and Wales and Austria. Population Studies-a Journal of Demography 2000;54:169–76. 10.1080/713779087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grundy E, Kravdal Ø. Reproductive history and mortality in late middle age among Norwegian men and women. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:271–9. 10.1093/aje/kwm295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaffe DH, Neumark YD, Eisenbach Z, et al. Parity-related mortality: shape of association among middle-aged and elderly men and women. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:9–16. 10.1007/s10654-008-9310-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersson G, Ronsen M, Knudsen LB, et al. Cohort fertility patterns in the Nordic countries. Demographic Research 2009;20:313–52. 10.4054/DemRes.2009.20.14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ulmanen P, Szebehely M. From the state to the family or to the market? Consequences of reduced residential eldercare in Sweden. Int J Soc Welf 2015;24:81–92. 10.1111/ijsw.12108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sundström G, Johansson L, Hassing LB. The shifting balance of long-term care in Sweden. Gerontologist 2002;42:350–5. 10.1093/geront/42.3.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grundy E, Kravdal O. Fertility history and cause-specific mortality: A register-based analysis of complete cohorts of Norwegian women and men. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:1847–57. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albrektsen G, Heuch I, Tretli S, et al. Breast cancer incidence before age 55 in relation to parity and age at first and last births: a prospective study of one million Norwegian women. Epidemiology 1994;5:604–11. 10.1097/00001648-199411000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ringbäck Weitoft G, Burström B, Rosén M. Premature mortality among lone fathers and childless men. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1449–59. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kendig H, Dykstra PA, van Gaalen RI, Melkas T. Health of aging parents and childless individuals. Journal of Family Issues 2007;28:1457–86. 10.1177/0192513X07303896 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manor O, Eisenbach Z, Israeli A, et al. Mortality differentials among women: the Israel Longitudinal Mortality Study. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:1175–88. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00024-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jasienska G, Nenko I, Jasienski M. Daughters increase longevity of fathers, but daughters and sons equally reduce longevity of mothers. Am J Hum Biol 2006;18:422–5. 10.1002/ajhb.20497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torssander J. From child to parent? The significance of children's education for their parents’ longevity. Demography 2013;50:637–59. 10.1007/s13524-012-0155-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christiansen SG. The impact of children's sex composition on parents’ mortality. BMC Public Health 2014;14:989 10.1186/1471-2458-14-989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dykstra PA, Hagestad GO. Childlessness and parenthood in two centuries: Different roads-different maps? Journal of Family Issues 2007;28:1518–32. 10.1177/0192513X07303881 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grundy E, Read S. Social contacts and receipt of help among older people in England: are there benefits of having more children? J Gerontol B-Psychol 2012;67:742–54. 10.1093/geronb/gbs082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McArdle PF, Pollin TI, O'Connell JR, et al. Does having children extend life span? A genealogical study of parity and longevity in the Amish. J Gerontol A-Biol 2006;61:190–5. 10.1093/gerona/61.2.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cesarini D, Lindqvist E, Wallace B. Is there an adverse effect of sons on maternal longevity? Proc Biol Sci 2009;276:2081–4. 10.1098/rspb.2009.0051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pham-Kanter G, Goldman N. Do sons reduce parental mortality? J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:710–5. 10.1136/jech.2010.123323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekbom A. The Swedish Multi-generation Register. Methods Mol Biol 2011;675:215–20. 10.1007/978-1-59745-423-0_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barefoot JC, Grønbaek M, Jensen G, et al. Social network diversity and risks of ischemic heart disease and total mortality: findings from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:960–7. 10.1093/aje/kwi128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Umberson D. Gender, marital-status and the social-control of health behavior. Soc Sci Med 1992;34:907–17. 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90259-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chudnovskaya M, Kolk M. Educational expansion and intergenerational proximity in Sweden. Population, Space and Place Epub ahead of print: 26 Aug 2015. 10.1002/psp.1973. 10.1002/psp.1973 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman EM, Mare RD. The schooling of offspring and the survival of parents. Demography 2014;51:1271–1293. 10.1007/s13524-014-0303-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zunzunegui MV, Beland F, Otero A. Support from children, living arrangements, self-rated health and depressive symptoms of older people in Spain. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:1090–9. 10.1093/ije/30.5.1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antonucci TC, Ajrouch KJ, Janevic MR. The effect of social relations with children on the education-health link in men and women aged 40 and over. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:949–60. 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00099-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krause N. Longitudinal study of social support and meaning in life. Psychol Aging 2007;22:456–69. 10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]