Abstract

Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) is a chronic pro-inflammatory autoimmune disease consisting of islet-infiltrating leukocytes involved in pancreatic β-cell lysis. One promising treatment for T1D is islet transplantation; however, clinical application is constrained due to limited islet availability, adverse effects of immunosuppressants, and declining graft survival. Islet encapsulation may provide an immunoprotective barrier to preserve islet function and prevent immune-mediated rejection after transplantation. We previously demonstrated that a novel cytoprotective nanothin multilayer coating for islet encapsulation consisting of tannic acid (TA), an immunomodulatory antioxidant, and poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) (PVPON), was efficacious in dampening in vitro immune responses involved in transplant rejection and preserving in vitro islet function. However, the ability of (PVPON/TA) to maintain islet function in vivo and reverse diabetes has not been tested. Recent evidence has demonstrated that modulation of redox status can affect pro-inflammatory immune responses. Therefore, we hypothesized that transplanted (PVPON/TA)-encapsulated islets can restore euglycemia to diabetic mice and provide an immunoprotective barrier. Our results demonstrate that (PVPON/TA) nanothin coatings can significantly decrease in vitro chemokine synthesis and diabetogenic T cell migration. Importantly, (PVPON/TA)-encapsulated islets restored euglycemia after transplantation into diabetic mice. Our results demonstrate that (PVPON/TA)-encapsulated islets may suppress immune responses and enhance islet allograft acceptance in patients with T1D.

Keywords: Reactive oxygen species, islet transplantation, chemokines, macrophage, Type 1 diabetes, and antioxidant

INTRODUCTION

Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disease characterized by the targeted lysis of insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells, in which patients are unable to maintain euglycemia without daily insulin injections or an insulin pump. Even the most meticulous methods of providing exogenous insulin can allow wide fluctuations in blood glucose that significantly alter metabolism and contribute to life threatening diabetic complications including cardiovascular disease, nephropathy, and retinopathy [1]. A viable alternative to exogenous insulin injection is pancreatic islet transplantation, a process that requires isolating islets from human cadaveric or porcine donors [2, 3]. The main advantage of islet transplantation is that the pancreatic β-cell is finely tuned to properly regulate blood glucose levels, and episodes of hyperglycemia (elevated blood glucose) and hypoglycemia (low blood glucose) are less frequent compared to exogenous insulin injection. Unfortunately, numerous challenges still exist with islet transplantation including islet viability, efficient engraftment, islet function, and preventing immune recognition of transplanted islet allo- or xenografts [4]. T1D patients require immunosuppressants to protect donor islets from rejection, but these immunotherapies can be toxic, decrease islet function, and increase the susceptibility to life threatening microbial infections [5].

One promising method to circumvent immune recognition after islet transplantation is to encapsulate islets in an immunoprotective coating that will prevent immune-mediated pancreatic islet destruction, but still afford islets the ability to maintain euglycemia. We previously demonstrated that islet encapsulation with a layer-by-layer conformal coating of tannic acid (TA), a natural polyphenol with antioxidant activity, hydrogen-bonded with the non-ionic poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) (PVPON) polymer, was non-toxic and maintained in vitro islet function [6, 7]. TA is an antioxidant that scavenges free radicals, inhibits free radical-induced oxidation, and can elicit immunomodulation [6]. Importantly, TA is also involved in the assembly of multilayer films, capsules, and coatings of biomedical relevance [8–16]. PVPON is biocompatible and has been used in drug delivery [17]. Similar to poly(ethylene glycol), PVPON has been shown to prevent protein absorption on the surfaces due to its hydrophilic nature [18]. In addition to dissipating reactive oxygen species (ROS) synthesis involved in pathological islet cell destruction, (PVPON/TA) can also influence the activation of redox-dependent signaling pathways that contribute to pro-inflammatory cytokine synthesis [19, 20]. More importantly, we showed that (PVPON/TA) multilayer coatings attenuated the synthesis of innate immune-derived pro-inflammatory cytokines and adaptive immune T cell effector responses involved in autoimmunity and islet rejection in vitro [6, 7]. As a natural antioxidant, TA assembled with PVPON may afford additional protection to insulin-secreting β-cells during oxidative stress since β-cells display an inherent decrease in antioxidant protection [21–24]. Similarly, dissipating local concentrations of ROS may also prevent the maturation of effector T cell responses involved in islet graft rejection including T cell activation markers and IFN-γ, a pro-inflammatory Th1 cytokine [25–29]. Therefore, studies to further define the role of (PVPON/TA) multilayer biomaterial on immune modulation and protection for pancreatic islet transplantation are highly warranted.

We recently demonstrated the importance of NADPH oxidase (NOX)-derived superoxide to promote a pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage phenotype involved in autoimmune destruction of pancreatic β-cells in T1D [30]. Our results and others [30, 31], provide evidence that oxidative stress during spontaneous autoimmune diabetes can influence the differentiation of classically-activated pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages and promote the synthesis of pancreatic β-cell damaging cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12p70, Type I interferons, and cell surface co-stimulatory molecules such as CD40, CD80, and CD86. Macrophages can facilitate the recruitment of other immune cells to sites of inflammation by the secretion of chemokines [32]. These secreted proteins play an integral role in the pathogenesis of T1D and islet transplant rejection by promoting cellular chemotaxis and immune cell migration to sites of newly transplanted islets and enhancing pancreatic β-cell necrosis. Many chemokines are associated with T1D pathogenesis, but one widely known β-cell destructive chemokine is CXCL10, which has been identified as a dominant chemokine involved in murine and human T1D [33]. The chemokine CCL5, also known as RANTES, plays a key role in T cell proliferation and recruitment of T cells in patients with T1D [34].

Despite the immunotherapeutic potential of hydrogen-bonded (PVPON/TA) multilayers for encapsulated islet transplants, little is known of the effects on chemokine production and pro-inflammatory macrophage differentiation in the presence of (PVPON/TA) multilayers. In the current study, we further demonstrate the ability of (PVPON/TA) multilayer capsules to decrease pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage responses and chemokine synthesis involved in leukocyte recruitment to potentially mitigate islet graft rejection. In addition, (PVPON/TA) multilayer encapsulation does not compromise in vivo islet function as demonstrated by the restoration of euglycemia following transplantation into immuno-deficient diabetic mice. Our results demonstrate that the antioxidant and immunomodulatory properties of (PVPON/TA) nanothin multilayer coatings can provide an immunoprotective shield on encapsulated islets to reduce diabetogenic T cell responses, and potentially protect encapsulated islets from transplant rejection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) (PVPON), (average Mw 1 300 000 g mol−1), tannic acid (TA), (Mw 1700 g mol−1), poly(methacrylic acid) (PMAA) (average Mw 21000 g mol−1), and mono- and dibasic sodium phosphate were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Ultrapure (Siemens) water with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ cm was used for preparation of buffered solutions. Silica micro particles of 4.0±0.1 μm in diameter were purchased from Cospheric. The BDC-2.5 mimotope (EKAHRPIWARMDAKK) was synthesized by Sigma Genosys. CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, and CCL5 DuoSet ELISA kits and CCL17 and CXCL10 antibody pairs were purchased from R&D Biosystems. Fluorochrome-conjugated anti-CD40, -CD80, -CD86, and –F4/80 antibodies were purchased from eBioscience, while biotin anti-mouse CD4, in addition to anti-F4/80-flurochrome-conjugated and live/dead fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen.

Mice

NOD/ShiLtJ, NOD.Cg-Tg(TcraBDC2.5,TcrbBDC2.5)/DoiJ (BDC-2.5), NOD.C6.Cg-Tg(TcraBDC6.9,TcrbBDC6.9)/DoiJ (C6.BDC-6.9), NOD.scid, and NOD.Rag mice were bred and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Research Support Building of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. BDC-2.5 and C6.BDC-6.9 mice were originally obtained from Dr. Kathryn Haskins at National Jewish Hospital (Denver, CO). NOD.scid and NOD.Rag mice purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were maintained on a light/dark (12hr/12hr) cycle at 23°C and received continuous access to standard lab chow and acidified water. Male and female mice between 7–9 weeks of age were used in all experiments in accordance with the University of Alabama-Birmingham and observing IACUC-approved mouse protocols and the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of Laboratory animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978).

Preparation of hydrogen-bonded (PVPON/TA) multilayer capsules

(PVPON/TA) multilayer hollow capsules were synthesized as previously described [6, 35] by incubating 1.5 mL of 10%-aqueous suspension of silica microspheres to PVPON (1 mg mL−1) solution (0.01 M sodium phosphate, pH=3.5) for 10 min. The silica particle suspension was subsequently pelleted and rinsed two times with 0.01 M sodium phosphate (pH=3.5) to remove unbound excess of polymer. Then, TA was allowed to adsorb onto particle surfaces from 0.5 mg mL−1 solution for 10 min. Following each deposited layer, particles were centrifuged (2 min, 2000 rcf) and rinsed two times with the rinsing solution (0.01 M sodium phosphate, pH=3.5). Alternating coating of particles with the polymers was continued until the desired number of layers was achieved. Multilayer capsules were obtained by dissolving (PVPON/TA) multilayer-coated silica cores in aqueous hydrofluoric acid (8% w/v) followed by their dialysis in de-ionized water for three days in the dark (Float-A-Lyzer MWCO=20 kDa, Spectrum Labs). Capsule shell configuration was (PVPON/TA)n where the subscript denotes a number of (PVPON/TA) bilayers deposited within the multilayer with TA as the outmost layer and was labeled as “4–5” for five-bilayer (PVPON/TA)5 capsules of 4 μm in diameter. An additional set of the (PVPON/TA)5.5 capsules was prepared using 4 μm sacrificial silica microspheres with PVPON as an outside layer, and labeled as “4–5.5”. A set of control capsules (PVPON)5 containing only PVPON was prepared using poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone)-co-(aminopropyl)methacrylamide) (PVPON-NH2) with weight-average molecular weight of 81000 g mol−1 and Ð = 1.54, and 4 μm sacrificial silica spheres as described previously [36]. Briefly, hydrogen-bonded multilayers PVPON-NH2-n, where n denotes a molar percentage of amine group-containing polymer units (n=7) were deposited on silica microspheres at pH=3.5, starting from PVPON-NH2. Each deposition cycle was followed by three rinses with a pH=3.5 buffer solution (0.01 M) to remove excess polymer, followed by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 2 min to remove supernatant. After five bilayers of (PVPON-NH2/PMAA) were deposited, chemical cross-linking of PVPON-NH2 layers was performed using glutaraldehyde solution (5 wt%) at pH=5 for 12 hours. After that, the coated particles were exposed to pH=8.5 for 4 hours to release PMAA, followed by rinsing at pH=4. The core dissolution was performed as described above and resultant capsules were purified by dialysis in deionized water for 3 days. All capsules were vortexed and sonicated (15 s each) three times before use. Concentration of the capsule suspensions (shells/microliter) was measured by capsule counting using a hemocytometer. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of the hollow capsules was performed using an FEI Quanta FEG SEM microscope at 10 kV. Samples were prepared by depositing a drop of a particle suspension on a silicon wafer and allowing it to dry overnight at room temperature. Before imaging, dried specimens were sputter-coated with a ∼5 nm thick silver layer using a Denton sputter-coater. The chemical composition, size, and capsule top layer of the (PVPON/TA) multilayer capsules are defined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition, size, and a capsule top layer of the (PVPON/TA) multilayer capsules.

| Sample | Capsule chemical composition | Capsule size, μm | Capsule top layer |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4-5 | (PVPON/TA)5 | 4 μm | TA |

| 4-5.5 | (PVPON/TA)5PVPON | 4 μm | PVPON |

| PVPON | (PVPON)5 | 4 μm | PVPON |

Islet isolation, encapsulation, and MTT assay

Islets from NOD.scid or NOD.Rag mice were isolated and encapsulated as previously described [7]. Non-encapsulated and encapsulated islet viability was assessed with an MTT assay (Sigma Aldrich) as described [6]. The conformal coating of islets with hydrogen-bonded (PVPON/TA)n multilayer film was performed at 25° C inside the laminar hood. Before deposition of (PVPON/TA)n multilayer coating, where n denotes the number of deposited bilayers, islets were pelleted in 1.5 mL Eppendorf centrifuge tubes and washed two times with rinsing solutions of islet culture media. PVPON was allowed to adsorb first onto islet surfaces from 1 mg mL−1 solution (RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS, 20mM HEPES, penicillin/streptomycin (100U/100mg/mL), 2mM L-glutamine, 50μM 2-mercapto-ethanol, 0.5% BSA w/v, pH = 7.4) for 7 min followed by the deposition of TA layer from 0.3 mg mL−1 solution (Freshly dissolved in the media before coating procedure, pH = 7.4) for 3 min. After each deposited layer, islets were collected by centrifugation for 2 min at 2000 rpm and rinsed twice with the islet media. Alternating coating of islets with the polymers was continued until the desired number of layers was achieved. All solutions were filter-sterilized with polystyrene non-pyrogenic membrane systems (0.22 μm pore size) (Corning) before use. Islets were encapsulated with 5 bilayers of (PVPON/TA) (the 4–5 configuration) with tannic acid on the outer layer prior to transplantation into diabetic recipient NOD.Rag mice.

Differentiation and stimulation of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BM-Mɸ)

Bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells were isolated from femurs and tibias of NOD mice and differentiated into macrophages using L-929 conditioned macrophage media as previously described [37]. Stem cells were plated in 24-well plates, petri dishes, and chamber slides at a concentration of 1.0 × 106 cells/mL. After 7 days, differentiated macrophages were cultured in macrophage media depleted of L-929 conditioned media for 24 hours prior to stimulation. Cells were then treated with 25 μg/mL of the TLR3 ligand, poly(I:C) (low-molecular-weight double stranded RNA synthetic analog, InvivoGen), and co-treated with 1.0×107 counts/mL of (PVPON/TA) capsules at various time intervals [38].

Chemotaxis assay

To assess CD4 T cell migration, BM-Mɸ were seeded and differentiated onto the lower chambers of a 24-well Corning transwell plate containing 8 μm pores. Splenic CD4 T cells from diabetogenic NOD.C6.BDC-6.9 mice were purified by negative selection according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the EasySep CD4 T cell enrichment kit (STEMCELL Technologies). CD4 T cell purity was routinely assessed by flow cytometry and found to be greater than 90% (data not shown). Following stimulation with p(I:C) in the presence or absence of (PVPON/TA) capsules for 24 hours, 2×105 C6.BDC-6.9 CD4 T cells were added to the upper chamber. Following incubation at 37°C for 24 hours, non-adherent T cells were collected from the lower chambers and counted via trypan blue exclusion.

Immuno-spin trapping and immunofluorescence

Macromolecule-centered free radicals were detected upon stimulating NOD bone marrow-derived macrophages with 25 μg/mL p(I:C) in the presence of 1mM 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO, Dojindo) in tissue culture-treated chamber slides. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS, blocked with 5% BSA in PBS, and incubated with 20 μg/mL of chicken IgY anti-DMPO as described [39, 40]. DMPO adducts were detected with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-chicken IgY secondary antibody (1:500; Invitrogen). Macrophages were identified with anti-F4/80 Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated antibody (1:500; Life Technologies). Images were obtained with an Olympus IX81 Inverted Microscope at a 40X objective and analyzed with cellSens Dimension imaging software version 1.12. To quantitate fluorescence intensity, 3–6 images were obtained for each data point. Each image was collected at the same exposure time, adjusted to the same intensity level for standardization, and the fluorescence intensity was measured using ImageJ Software (NIH).

ELISA and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Chemokine expression was measured in the supernatants of stimulated macrophages for 72 hours as described [41]. Pro-inflammatory CCL5 and CXCL10 chemokines were detected with DuoSet ELISA kit and antibody pairs (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. ELISA plates were read on a Synergy 2 microplate reader (BioTek) using Gen5 software. RNA was isolated from poly(I:C)-stimulated and (PVPON/TA) capsule-treated BM-Mɸ after 48 hours incubation using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and cDNA prepared by SuperScript III (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The generated cDNA was amplified on a Roche LightCycler 480 instrument by qRT-PCR using the following TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems): Emr1 (Mm00802529), Ccl2 (Mm00441242), Ccl3 (Mm00441259), Ccl4 (Mm00443111), Ccl5 (Mm01302428), Ccl17 (Mm00516136), Cxcl10 (Mm00445235). The relative mRNA levels were calculated with 2−ΔΔCt method and Emr1 was used as a housekeeping control gene for normalization [38]. The unstimulated samples were used as calibrator controls and set as 1.

Flow cytometric analysis of macrophage markers

Following p(I:C) stimulation, 1×106 BM-Mϕs were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for F4/80 (BM8), CD40 (1C10), CD80 (16-10A1), and CD86 (PO3.1) (BD Biosciences, eBiosciences) for 30 minutes at 4°C as described previously [38]. Cells were collected on the Attune NxT Flow Cytometer (ThermoFisher) with at least 100,000 events collected for each sample and analyzed with FlowJo (10.0.8r1) software (Tree Star, Inc.).

Differentiation of NOD dendritic cells and co-culture with BDC-2.5 CD4 T cells and encapsulated NOD.Rag islets

Bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells were isolated from femurs and tibias of NOD mice and differentiated into dendritic cells (DCs) using IL-4 and GM-CSF, as described previously [42]. Before culture with CD4 T cells, DCs were stimulated with 1 μg/mL LPS for 6 hours at 37°C with 5% CO2. Splenic CD4 T cells from NOD.BDC-2.5 mice were purified by negative selection according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the EasySep CD4 T cell enrichment kit (STEMCELL Technologies). CD4 T cell purity was routinely assessed by flow cytometry and found to be greater than 90% (data not shown). CD4 T cells (5×105) were cultured with 3.75×105 DCs in the presence or absence of non-encapsulated and encapsulated (4–5 and 4–5.5 PVPON/TA multilayers) NOD.Rag islets, in addition to the BDC-2.5 mimotope. Culture supernatants were harvested at 48 and 72 hours post-stimulation. Culture supernatants were harvested at 48 hours post-stimulation.

Streptozotocin (STZ) induction of diabetes, islet transplantation, and histology

To induce diabetes in NOD.Rag mice, 175 mg/kg STZ (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS (pH 7.2) was injected intraperitoneally. Mice were considered diabetic after two consecutive positive glucosuria tests with Diastix (Bayer) and confirmed with blood glucose readings ≥ 300 mg/dL (19.8 mM) with a Breeze 2 blood glucose meter (Bayer). Euglycemia was restored by transplanting 500 (PVPON/TA)-encapsulated NOD.scid islets into the epididymal fat pad of diabetic NOD.Rag mice (n=5 for each group of transplanted or non-transplanted recipient mice) under isoflurane anesthesia as described [43]. Epididymal fat pads containing transplanted islets were excised, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours, embedded in paraffin or Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT, Tissue-Tek), sectioned at 6–8μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin as described [44]. Cut paraffin sections were rehydrated and then blocked with 5% normal donkey serum in 1% BSA/1X PBS. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C: mouse anti-glucagon (1:4000, #G2654, Sigma), guinea pig anti-insulin (1:1000, #A056401-2, Dako). Cy2-, Cy3, or Cy5-conjugated donkey anti-guinea pig, anti-mouse, or anti-goat IgG secondary antibodies (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were used for detection. Slides were imaged using an Olympus IX81 inverted microscope (Olympus) and the images were processed by CellSens Dimensions software version 1.12 (Olympus).

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT)

An IPGTT assay was performed as we described [26]. Male NOD.scid mice were fasted for 6 hours, weighed, and injected intraperitoneally with 2 g/kg body weight of 20% D-glucose (Sigma-Aldrich). Blood was obtained from the tail vein before and at 5, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after glucose injection and blood glucose was measured with a Breeze 2 blood glucose meter (Bayer).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism Version 5.0 statistical software. Determination of the difference between mean values and standard deviation for each experimental group was assessed using the 2-tailed Student’s t test, with p < 0.05 considered significant. All experiments were performed at least three separate times with data obtained in a minimum of triplicate wells in each experiment.

RESULTS

(PVPON/TA) multilayer capsules elicit a reduction in macromolecular free radical adducts in p(I:C)-stimulated bone marrow-derived macrophages (BM-Mϕ)

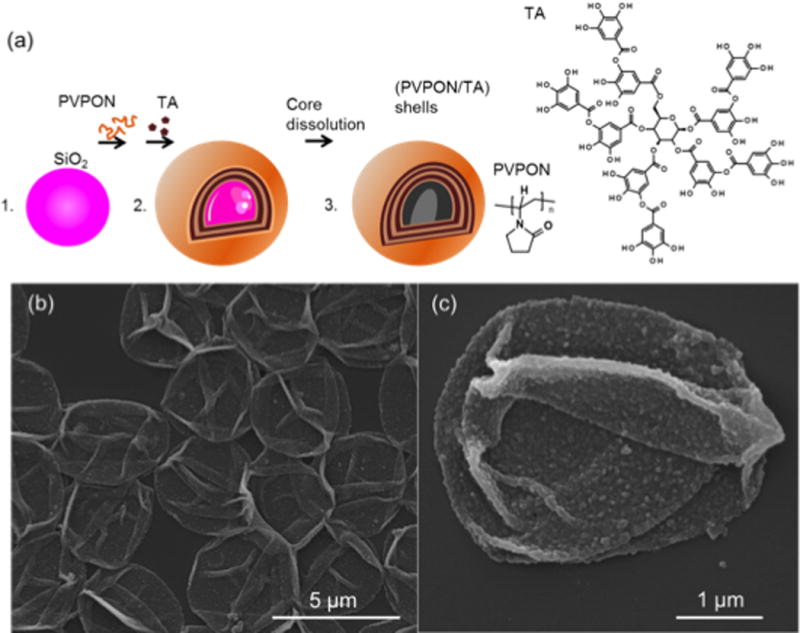

To investigate the antioxidant effect of (PVPON/TA) multilayer capsules on p(I:C)-stimulated bone marrow-derived macrophages (BM-Mϕ), hollow multilayer capsules with varied composition were prepared using a hydrogen-bonded assembly of PVPON and TA on sacrificial silica particles of 4 μm in diameter as we previously described [6, 7] (Figure 1A). After dissolution of the silica cores followed by their dialysis in water, hollow multilayer capsules were obtained. Scanning electron microscopy analysis confirmed a complete removal of the inorganic templates and the (PVPON/TA) hollow shells collapsed upon drying on surfaces of a Si wafer (Figure 1B). Figure 1C demonstrates a rough surface topography of the (PVPON/TA) shell in agreement with our previous data [35]. The average bilayer thickness of the (PVPON/TA) capsules produced at pH≤5 (0.01 M) is 7.5 nm as previously measured by atomic force microscopy [35]. The 4 μm capsules with the capsule top layer being either TA as in (PVPON/TA)5, or PVPON as in (PVPON/TA)5PVPON were prepared and labeled as ‘4–5’ and ‘4–5.5’, respectively (Table 1). As a non-functional control, we used 5-layer (PVPON)5 multilayer capsules that did not contain any TA as a capsule wall constituent and were labeled as ‘PVPON’.

Figure 1. Schematic demonstrating the synthesis of (PVPON/TA) multilayer coatings.

Hollow multilayer shells of (PVPON/TA)n (n = 5 and 5.5; and denotes the number of PVPON/TA bilayers in the multilayer) were produced via hydrogen-bonded assembly of PVPON and TA on surfaces of silica particles (SiO2) of 4 μm, followed by dissolution of the silica core and dialysis of (PVPON/TA)n shells at pH=7.4 (A). Scanning electron microscopy images of the dried (PVPON/TA)5 polymeric shells (B, C).

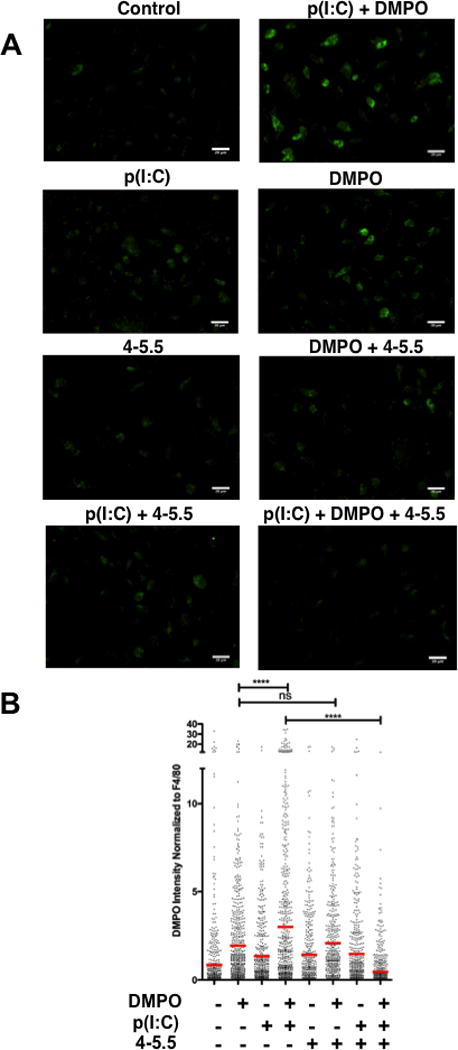

To confirm that the inner layer location of TA in the 4–5.5 multilayer capsules can effectively dissipate NOX-derived superoxide synthesis, immuno-spin trapping was performed with the free radical spin trap, dimethyl pyrroline oxide (DMPO), to verify the generation of free radicals in macromolecules in BM-Mϕ upon stimulation with Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists [28, 44]. Corroborating our previous studies, there was a 1.5-fold increase in DMPO-adducts after stimulation with p(I:C), a TLR3 agonist [7]. Co-treatment with (PVPON/TA) elicited a significant 6.5-fold decrease in DMPO-adducts via immunofluorescence with p(I:C)-treated macrophages in contrast to p(I:C) stimulation alone (Figure 2A). In Figure 2B, quantitation of DMPO-adduct fluorescence intensity revealed a significant reduction when p(I:C)-stimulated macrophages were treated in the presence of (PVPON/TA) capsules. The decrease in fluorescence intensity demonstrates that (PVPON/TA) capsules are effective in dissipating free radical synthesis and may be efficacious in modulating pro-inflammatory innate immune responses of macrophages.

Figure 2. (PVPON/TA) multilayers reduce macromolecule-centered free radical formation upon p(I:C) stimulation.

Immunofluorescence identification of macrophages (F4/80 - Alexa Fluor 647) and DMPO adducts (Alexa Fluor 488) of 25 μg/mL p(I:C)-stimulated NOD bone marrow-derived macrophages co-treated with 1mM DMPO and capsule 4-5.5 for 12 hours (A). The fluorescence intensity of DMPO adducts by immune cells were quantitated with ImageJ software (B). Data shown represent average of 3 experiments performed in triplicate with the following total number of counted cells per group (Control: n=599; DMPO: n=632; p(I:C): n=526; p(I:C) + DMPO: n=697; capsule 4-5.5: n=429; capsule 4-5.5 + DMPO: n=461; p(I:C) + capsule 4-5.5: n=457; p(I:C) + capsule 4-5.5 + DMPO: n=652). The red bar corresponds to the mean fluorescence intensity of DMPO-adducts normalized to macrophages expressing F4/80. Images were magnified at 40X and digitally enlarged. ns, not significant; ****p<0.0001

Pro-inflammatory chemokine expression was dampened in the presence of (PVPON/TA) multilayer capsules

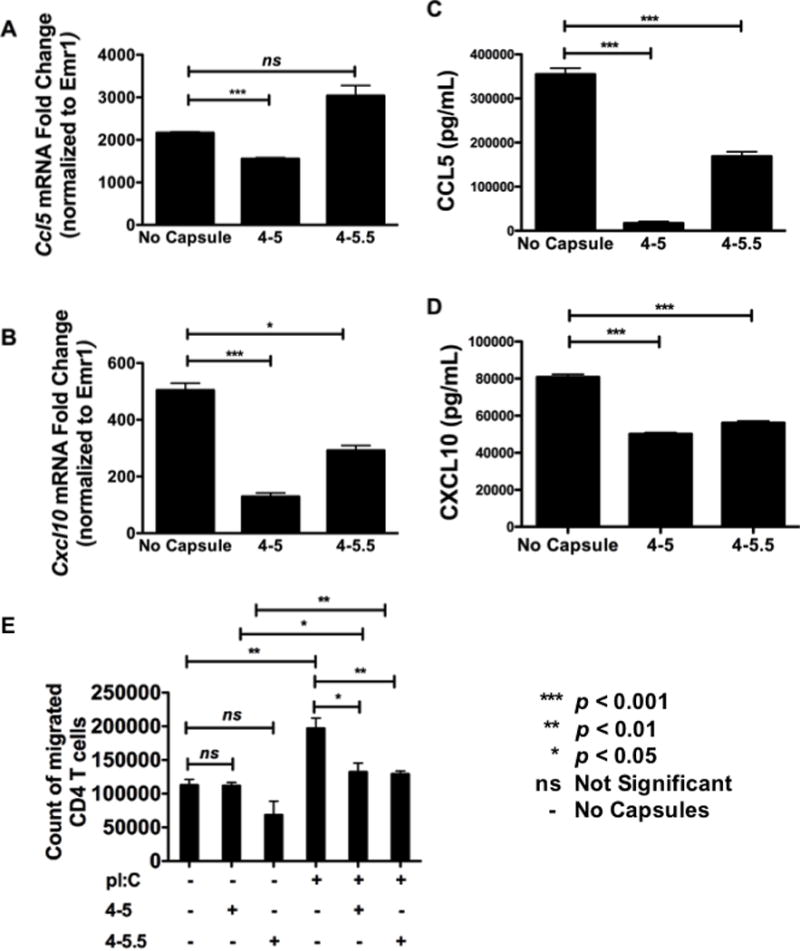

As pro-inflammatory chemokine synthesis is redox-regulated [41] and (PVPON/TA) nanothin multilayer coatings can function as an antioxidant to dissipate free radicals (Figure 1 and [7]), the ability of (PVPON/TA)n to regulate pro-inflammatory chemokines implicated in islet transplant rejection within p(I:C)-stimulated BM-Mϕ was examined by qRT-PCR and ELISA. Expression of CCL5 and CXCL10 mRNA accumulation and protein expression by qRT-PCR and ELISA, respectively, was significantly lowered when p(I:C)-stimulated samples were treated with (PVPON/TA)n capsules (Figure 3). Interestingly, differences were observed when macrophages were co-treated with (PVPON/TA)5 capsules containing TA on the top (4–5) or shielded by the PVPON outer layer (4–5.5). At 48 hours post-stimulation, Ccl5 mRNA levels were significantly reduced 1.4-fold with capsule 4–5, but no significant difference was observed with capsule 4–5.5 (Figure 3A). Similarly, in Figure 3B, Cxcl10 mRNA accumulation was attenuated 2.6- and 1.7-fold with 4–5 and 4–5.5, respectively. To corroborate the decrease in chemokine mRNA, CCL5 and CXCL10 protein levels were suppressed consistently over a period of 96 hours (data not shown) by 4–5 and 4–5.5 capsules. At 72 hours post-stimulation, CCL5 was reduced with capsules 4–5 and 4–5.5 by 20.6- and 2-fold, respectively (Figure 3C). CXCL10 protein levels followed similar results with a 1.6- and 1.4-fold reduction with capsules 4–5 and 4–5.5, respectively (Figure 3D). To further demonstrate that CXCL10 chemokine levels were redox-regulated, p(I:C)-stimulated macrophages were also stimulated with PVPON capsules alone and unlike capsules 4–5 and 4–5.5, the absence of tannic acid was not able to diminish Cxcl10 mRNA accumulation or CXCL10 expression (Supplemental Figure 2). CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, and CCL17 mRNA and chemokine levels did not differ when p(I:C)-stimulated macrophages were treated with 4–5 and 4–5.5 capsules (data not shown).

Figure 3. Pro-inflammatory chemokine synthesis and T cell migration is reduced in p(I:C)-stimulated macrophages co-treated with (PVPON/TA) multilayers.

Ccl5 (A) and Cxcl10 (B) mRNA accumulation from (PVPON/TA)-treated bone marrow-derived macrophages was examined by qRT-PCR after 48-hour stimulation with 25μg/mL of p(I:C). Results were normalized to Emr1 and the unstimulated samples were set to 1 and used as the calibrator control. Supernatant of (PVPON/TA)-treated bone marrow-derived macrophages stimulated at 25μg/mL of p(I:C) was examined via ELISA. CCL5 (C) and CXCL10 (D) chemokine expression at 72 hours was normalized to the no antigen/no capsules control group. Migration of CD4 T cells to the bottom chamber of a transwell plate containing bone marrow-derived macrophages primed with p(I:C) in the presence or absence of 4-5 and 4-5.5 (PVPON/TA)-containing capsules following 24 hour incubation (E). Graphed data represents cell counts via trypan blue exclusion from 4 individual wells. Graphed data are representative of 3 independent experiments done in at least triplicates. ns, not significant; ND, not detected; ***p<0.0001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05.

(PVPON/TA) multilayers can prevent T cell migration and chemotaxis

To corroborate the observed attenuated levels of pro-inflammatory chemokines elicited by (PVPON/TA) capsule treatment on p(I:C)-stimulated macrophages, a chemotaxis assay was performed with purified autoreactive CD4 T cells from the NOD.C6.BDC-6.9 mouse [45, 46] on a trans-well plate. The ability of diabetogenic C6.BDC-6.9 CD4 T cells to migrate from the top trans-well to the bottom chamber was assessed after stimulating NOD BM-Mϕ with p(I:C) in the presence or absence of 4–5 and 4–5.5 capsules by cell counting. As shown in Figure 3E, treatment of p(I:C)-stimulated macrophages with capsules 4–5 or 4–5.5 significantly decreased the number of migrated CD4+ T cells to the bottom chamber of the trans-well plate by 1.5-fold.

M1 activation markers were reduced in the presence of (PVPON/TA) multilayers

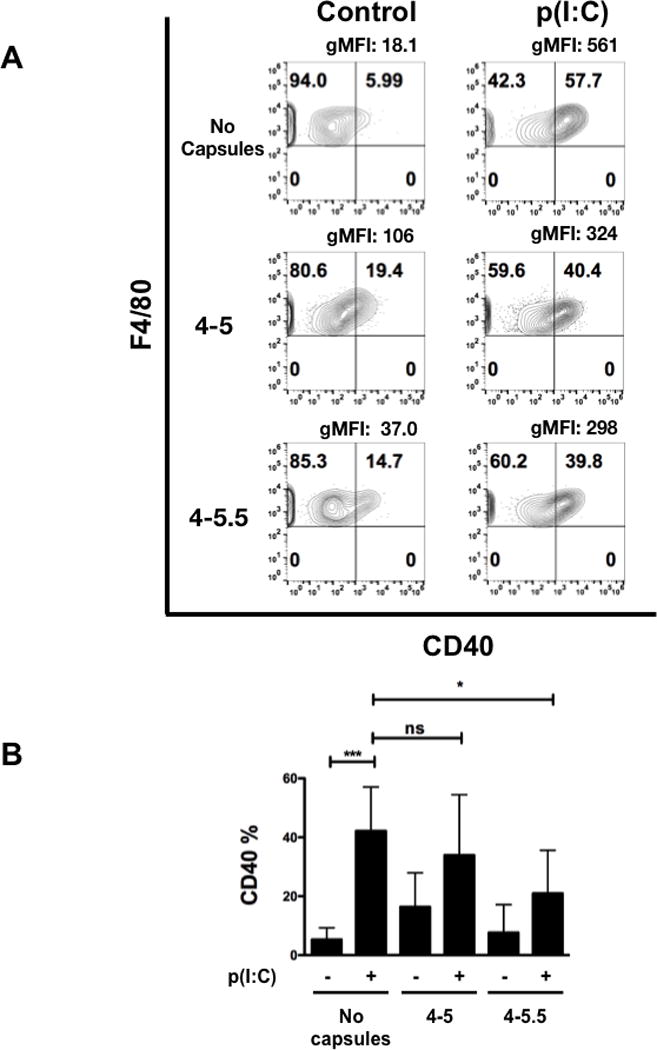

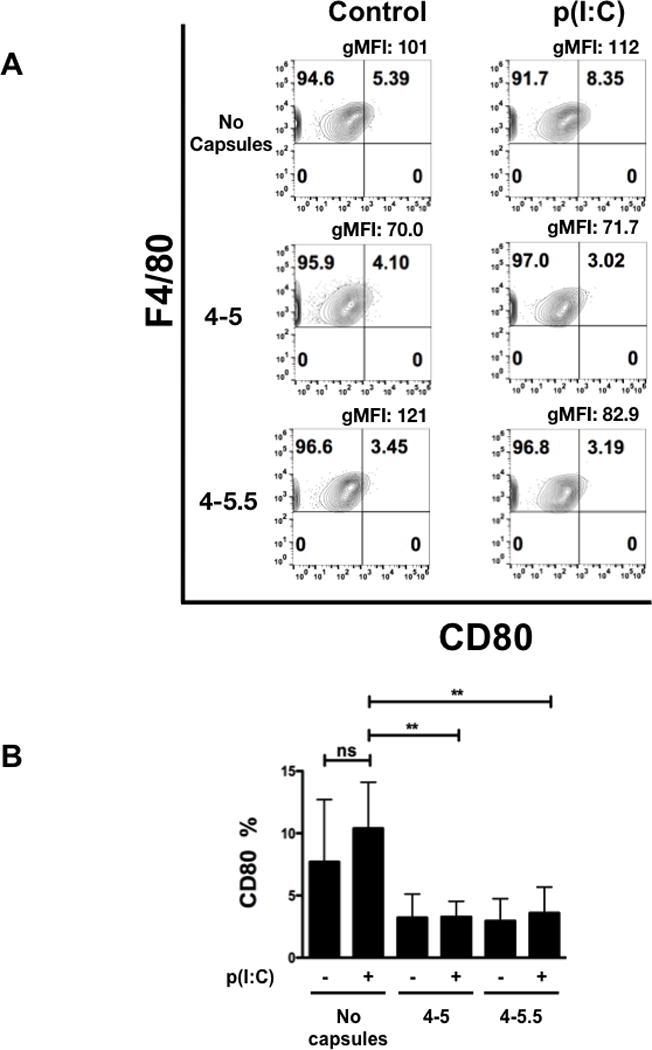

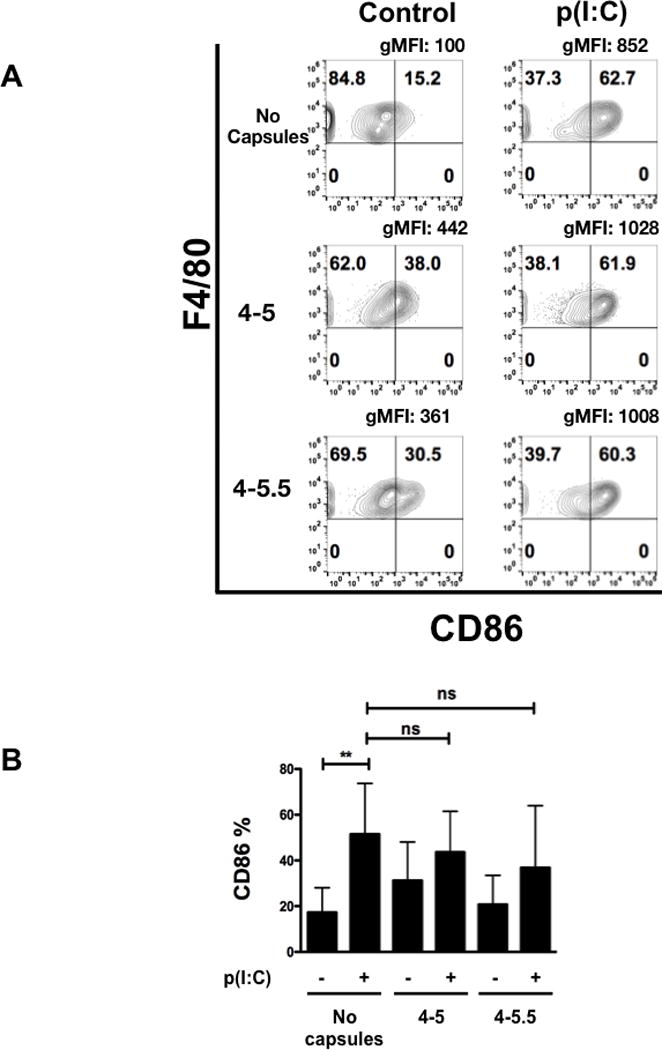

To further characterize the functional effects of (PVPON/TA) nanothin coatings on pro-inflammatory macrophage responses, surface expression of macrophage activation markers CD40, CD80, and CD86 were examined by flow cytometry at 24 hours post-stimulation with p(I:C) according to the gating strategy in Supplementary Figure 1. BM-Mϕ were immunophenotyped based on their size (FSC), granularity (SSC), single cells, live cells, and then gated on F4/80, a mouse macrophage-specific cell surface marker. Expression of CD40, CD80, and CD86, extracellular pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage cell surface markers that indicate these innate immune cells are activated, were diminished upon (PVPON/TA) co-treatment. Capsules 4-5 and 4-5.5 induced a 2.5- and 4.7-fold reduction in the geometric mean fluorescence intensity (gMFI) and a 1.2- and 2-fold decrease, respectively, in the percentage of F4/80 and CD40 positive cells in contrast to p(I:C) stimulation alone at 24 hours post-stimulation (Figure 4A). Interestingly, only capsule 4–5.5 elicited a statistically significant 2-fold decrease in the percentage of F4/80+ and CD40+ cells upon quantitation in Figure 4B. Similarly, treatment of p(I:C)-stimulated macrophages with capsules 4–5 and 4–5.5 exhibited a 1.5- and 1.4-fold reduction in the gMFI and 3.2- and 2.9-fold decrease, respectively, in the percentage of F4/80 and CD80 expression, a macrophage co-stimulatory molecule necessary for T cell activation (Figure 5A). Quantitation of the percentage of F4/80+ and CD80+ macrophages in comparison to p(I:C) treatment alone demonstrates that both capsules 4–5 and 4–5.5 significantly decreased expression by 2.5-fold (Figure 5B). With respect to CD86 expression, this co-stimulatory molecule was upregulated after p(I:C) stimulation on F4/80+ macrophages (Figure 6A), but co-treatment with capsules 4–5 and 4–5.5 elicited a trend toward a decrease that was not statistically significant (Figure 6B). In addition to decreasing pro-inflammatory chemokine synthesis, treatment with (PVPON/TA) capsules diminished M1 macrophage activation markers, thereby demonstrating the potential to immunomodulate in vivo innate immune responses.

Figure 4. Treatment of p(I:C)-stimulated macrophages with (PVPON/TA) multilayers dampens expression of the M1 activation marker CD40.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD40 within p(I:C) stimulated BM-Mϕs in the presence or absence of (PVPON/TA) capsules for 24 hours (A). Contour plots represent CD40 by F4/80 of live, F4/80+ macrophages. Geometric mean fluorescence intensity (gMFI) was calculated by gating on F4/80+ cells. Macrophages were gated using forward scatter and side scatter profiles, doublets were excluded, and live cells were gated using side scatter profiles using a fixable live/dead stain, immunophenotyped by F4/80. Pooled CD40 percentages represent 3 independent experiments, depicting the percentage of CD40 expressing cells gated on the live, F4/80+ population (B). ns, not significant; ***p<0.001; *p<0.05.

Figure 5. (PVPON/TA) multilayers can elicit a decrease in the extracellular M1 macrophage marker CD80 with p(I:C)-stimulated macrophages.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD80 within p(I:C)-stimulated BM-Mϕs in the presence or absence of (PVPON/TA) capsules for 24 hours (A). Macrophages were gated using forward scatter and side scatter profiles, doublets were excluded, and live cells were gated using side scatter profiles using a fixable live/dead stain, immunophenotyped by F4/80, and CD80 cell surface marker activation shown via percentage and geometric mean fluorescence intensity (gMFI). Pooled CD80 percentages represent 3 independent experiments done in triplicates depicting the percentage of CD80 expressing cells gated on the F4/80 population (B). ns, not significant; **p<0.01.

Figure 6. CD86 expression is not diminished when p(I:C)-stimulated macrophages are in the presence of (PVPON/TA) multilayers.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD86 within p(I:C)-stimulated BM-Mϕs in the presence or absence of (PVPON/TA) capsules for 24 hours (A). Macrophages were gated using forward scatter and side scatter profiles, doublets were excluded, and live cells were gated using side scatter profiles using a fixable live/dead stain (Invitrogen), immunophenotyped by F4/80, and CD86 cell surface marker activation is shown via percentage and geometric mean fluorescence intensity (gMFI). Pooled CD86 percentages represent 3 independent experiments done in triplicates depicting the percentage of CD86 expressing cells gated on the F4/80 population (B). ns, not significant; **p<0.01.

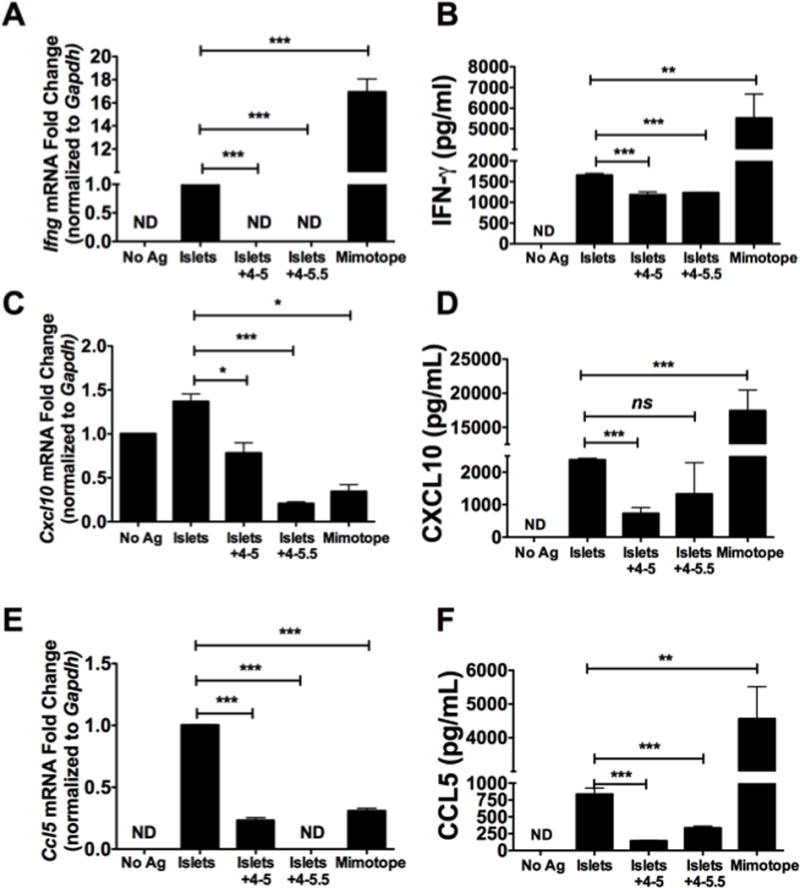

(PVPON/TA)-encapsulated islets are immuno-protected in co-culture assays with diabetogenic splenocytes

We previously demonstrated that (PVPON/TA)n multilayers with n≥3.5 can conformally coat the surfaces of murine, non-human primate, and human islets using confocal laser microscopy [7]. Transmission electron analysis of coated islets displayed a conformal coating with an average thickness of 7 nm per (PVPON/TA) bilayer which correlated well with atomic force microscopy analysis of the thickness of (PVPON/TA) hollow shells produced at physiological conditions of pH=7.2 (0.1 M) with a (PVPON/TA) capsule bilayer thickness of 8 nm [35]. Our data demonstrated the ability of (PVPON/TA) multilayers to diminish both innate and adaptive immune responses involved in pancreatic β-cell destruction. We have previously shown that (PVPON/TA) encapsulation of murine, non-human primate, and human islets did not alter β-cell function and the secretion of insulin in response to hyperglycemic conditions [7], but whether (PVPON/TA) multilayers applied to islet surfaces could function as an immunoprotective “shield” in the presence of autoreactive immune cells is not known. To address this question, NOD.Rag islets were encapsulated with 4–5 or 4–5.5 multilayers and incubated with diabetogenic BDC-2.5 splenocytes. As we previously described [6, 7], islet encapsulation with (PVPON/TA) multilayers did not affect the viability of NOD.Rag islets as shown by an MTT assay (data not shown) nor compromise islet function [7]. In contrast to non-encapsulated islets, 4–5- and 4–5.5-encapsulated NOD.Rag islets were more immuno-protected as Ifng mRNA accumulation was undetected (Fig. 7A), and protein synthesis was blunted 1.4- and 1.3-fold, with 4–5 and 4–5.5 multilayers, respectively (Fig. 7B). Cxcl10 mRNA was similarly reduced 1.8- and 6.5-fold, respectively upon islet encapsulation with 4–5 and 4–5.5 biomaterials (Fig. 7C), and CXCL10 synthesis was attenuated 3.3-fold upon encapsulation with biomaterials containing TA as the outermost layer (Fig. 7D). There was no statistically significant difference in CXCL10 synthesis upon culture with islets encapsulated with PVPON as the outermost layer (Fig 7D). In addition to CXCL10, the pro-inflammatory chemokine CCL5 was similarly attenuated at levels of transcription and translation upon islet encapsulation with PVPON/TA multilayers containing TA (4–5) or PVPON (4–5.5) on the outermost layer (Figure 7E, F). (PVPON/TA) encapsulation of NOD.Rag islets did not mediate an increased regulatory T cell (Treg) response in this co-culture assay, as the levels of IL-10 and FoxP3 expression on CD4 T cells was not altered (data not shown). These results provide additional evidence that encapsulation of islets with (PVPON/TA) multilayers prior to transplantation has the potential to dampen pro-inflammatory Th1 cytokine and chemokine responses involved in islet graft rejection.

Figure 7. Islet encapsulation with (PVPON/TA) is immunoprotective.

Ifng mRNA accumulation (A), IFN-γ synthesis (B), Cxcl10 mRNA accumulation (C), CXCL10 production (D), Ccl5 mRNA (E), and CCL5 protein production (F) within purified BDC-2.5 CD4 T cells cultured with LPS-primed NOD bone marrow-derived dendritic cells, and (PVPON/TA)-encapsulated islets with multilayer configurations of 4-5 and 4-5.5. qRT-PCR results were normalized to Gapdh and the unstimulated or islet-stimulated samples were set to 1 and used as the calibrator control. Graphed data represent 3 independent experiments done in triplicates. ns, not significant; ND, not detected; ns, not significant; ***p<0.001; **p<0.01.

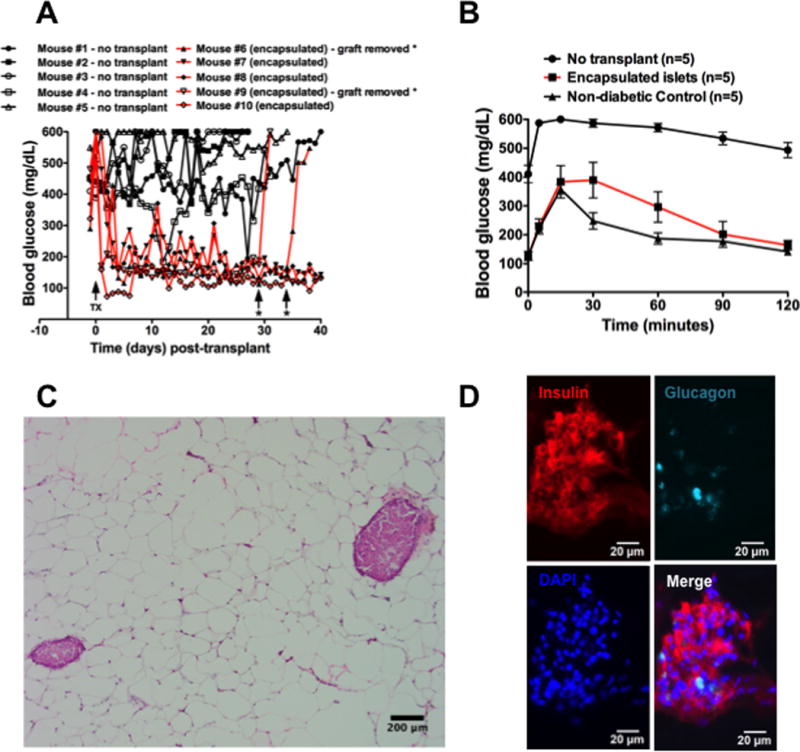

(PVPON/TA)-encapsulated islets are functional in vivo

To further examine the functional effects of (PVPON/TA) nanothin coatings, the ability of (PVPON/TA) encapsulated islets to reverse hyperglycemia in immunodeficient diabetic mice was examined. NOD.scid islets were encapsulated with (PVPON/TA) multilayers and transplanted in the epididymal fat pad of streptozotocin-treated diabetic NOD.Rag recipients (Figure 8A). Transplantation of 500 (PVPON/TA)-encapsulated islets efficiently restored diabetic NOD.Rag recipients to euglycemia by 2 days post-transfer. Reestablished islet function was also confirmed by performing an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test as we previously described [26]. Transplantation of (PVPON/TA)-encapsulated islets efficiently restored glucose tolerance when challenged with a bolus dose of glucose (Figure 8B). Removal of the epididymal fat pad (denoted as * in mouse #6 and #9) containing the islet transplant resulted in mice returning to hyperglycemia (Figure 8A). Histological analysis of the epididymal fat pad demonstrated stable engraftment of transplanted islets and expression of insulin and glucagon by immunofluorescence with (PVPON/TA)-encapsulated islets (Figure 8C, 8D). These results provide evidence that encapsulation of islets with (PVPON/TA) multilayers can maintain islet function in vivo and restore euglycemia in diabetic mice.

Figure 8. Transplantation of (PVPON/TA)-encapsulated islets can restore euglycemia to diabetic mice.

Daily blood glucose readings of streptozotocin-treated NOD.Rag mice before and after islet transplantation in the epididymal fat pad with 500 NOD.scid islets encapsulated in (PVPON/TA) (A). IPGTT assay with non-transplanted diabetic (n=5), euglycemic mice transplanted with encapsulated islets (n=5), and non-diabetic controls (n=5) (B). H&E stain (C) and immunofluorescence for insulin, glucagon, and DAPI (D) of (PVPON/TA)-encapsulated islets in the epididymal fat pad at 10X (C) and 40X (D) magnification. TX – islet transplant. * - islet graft removed.

DISCUSSION

These results demonstrate the importance of (PVPON/TA) multilayer biomaterials as a novel islet encapsulation nanothin coating to mediate immunosuppression by blunting pro-inflammatory chemokine expression, T cell trafficking, and maintaining islet function in vivo. In addition to a decrease in innate immune pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12p70 and TNF-α [7], and the Th1 adaptive immune effector cytokine IFN-γ [6], our results demonstrate that autoreactive T cell migration is impaired with (PVPON/TA) multilayers. CXCL10 and CCL5 pro-inflammatory chemokine synthesis is decreased at the mRNA and protein levels after (PVPON/TA) capsule treatment with p(I:C)-stimulated macrophages. Functionally, the decrease in pro-inflammatory chemokine production impacted the ability of diabetogenic CD4 T cells to migrate across a trans-well membrane, further highlighting the additional immunosuppressive effects elicited by (PVPON/TA) multilayers including dissipating free radicals and suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine synthesis [6, 7]. The significance of reducing these inflammatory molecules is that CXCL10 and CCL5 are important chemokines involved in the immunopathogenesis of T1D and islet graft rejection [32, 47–51]. In the serum of T1D patients, CXCL10 levels are elevated, suggesting that CXCL10 is a probable marker for predicting T1D [33]. Increases in CCL5 serum levels in patients with T1D have been associated with disease progression [34]. Within the human and murine islet microenvironment, expression of CXCL10 and CCL5 are key contributors to pancreatic β-cell destruction in autoimmune diabetes [52]. These results provide additional evidence of the immunomodulatory potential of (PVPON/TA) biomaterials to dissipate ROS, reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and also hinder T cell migration to sites of islet engraftment.

In support of our recent data demonstrating the importance of NOX-derived superoxide and oxidative stress on influencing pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage differentiation [30], we provide evidence that dissipation of free radicals with (PVPON/TA) coatings can also suppress CD40 and CD80 M1 macrophage activation markers. Expression of CD40 and CD80 are indicative of an M1 macrophage phenotype [53, 54], and the ability of 4–5 and 4–5.5 capsules to mediate this decreased pro-inflammatory macrophage response further highlights the importance of free radicals and oxidative stress on M1 macrophage differentiation [30, 31, 55]. Interestingly, the inability of 4–5 and 4–5.5 multilayers to blunt CD86 expression on p(I:C)-stimulated macrophages demonstrates that (PVPON/TA) nanothin coatings are not globally immunosuppressive and can still enable macrophages to function as antigen-presenting cells to stimulate T cells. The preferential decrease in CD40 and CD80 expression without compromising CD86 levels was also observed with LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages treated with triethylene glycol dimethacrylate, a monomer used in dental resins that can alter redox status [56–58]. Overall, the decrease in CD40 and CD80 levels supports the overarching hypothesis that the (PVPON/TA) multilayers are efficient in dampening pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage differentiation and activation.

Surprisingly, we did not observe a dramatic difference in T cell migration or CXCL10 synthesis and CD80 expression on p(I:C)-stimulated macrophages when tannic acid was located on the top (4–5) or inner (4–5.5) layer of the (PVPON) multilayers. However, differences were observed with Ccl5 mRNA accumulation and with CCL5 protein levels between 4–5 and 4–5.5, as tannic acid in the inner layer was less efficient in decreasing Ccl5 mRNA accumulation and protein synthesis in contrast to the outer layer. This observation would suggest that CCL5 expression is tightly regulated by tannic acid redox activity and oxidative stress. Previous studies have demonstrated a decrease in GSH antioxidant levels and a concomitant increase in CCL5 serum levels in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, a systemic autoimmune disease [59]. An additional redox-dependent mechanism of CCL5 synthesis includes an NF-κB-dependent response element in the promoter of the Ccl5 gene [60] and interestingly, the presence of five tyrosine amino acids within CCL5 can undergo oxidative post-translational modification and the formation of CCL5 multimers that are essential for chemokine activity [61]. Therefore, under conditions of oxidative stress and inflammation, biologically active oligomers of CCL5 are generated to enhance T cell trafficking, but in the presence of an antioxidant such as tannic acid, the formation of CCL5 multimers is decreased and T cell chemotaxis is diminished. Conversely, tannic acid localization in the inner layer was able to significantly decrease CD40 expression in p(I:C)-stimulated macrophages more efficiently than the outer layer, which may suggest that PVPON may inherently possess immunomodulatory effects. However, this is unlikely since we previously demonstrated that PVPON was unable to dissipate free radicals in the absence of tannic acid [6]. Alternatively, the antioxidant activity of tannic acid on the outer layer is not ideal to suppress CD40 expression and may be more responsive to suppressive effects when shielded by a PVPON layer. Future studies will involve altering the concentration of tannic acid on (PVPON/TA) multilayers to further define the ideal immunosuppressive effect on innate and adaptive immune responses.

In addition to decreasing diabetogenic CD4 T cell migration and macrophage activation, we mechanistically demonstrated that encapsulation of murine islets with (PVPON/TA) was immunoprotective and efficient in preventing Th1 effector responses involved in destroying pancreatic islets [6]. Paralleling our previous report demonstrating that encapsulation with (PVPON/TA) did not compromise, but enhanced islet function [7], we anticipate that islets encapsulated in (PVPON/TA) will facilitate the restoration of euglycemia and mediate immunosuppression. Furthermore, the inherent ability of polyphenolic compounds such as tannic acid to impart immunoregulatory responses is highly novel and may be efficacious in combination with lower doses of immunotherapeutics including tacrolimus, rapamycin, anti-thymocyte globulin, anti-CD25 (daclizumab), and anti-CD20 (rituximab) for stable islet transplant engraftment and protection from immune destruction [2, 62–64].

Finally, (PVPON/TA) encapsulation of islets did not compromise islet function in vivo, as euglycemia was quickly restored in diabetic mice after transplantation into the epididymal fat pad. These results demonstrate the feasibility of islet encapsulation with (PVPON/TA) nanothin coatings to maintain euglycemia in vivo and to modulate pro-inflammatory immune responses involved in islet graft destruction. Current studies are underway to determine the efficacy of (PVPON/TA)-encapsulated islets to delay both alloimmune and autoimmune responses after transplantation into spontaneously diabetic NOD or STZ-induced diabetic C57BL/6 mice.

CONCLUSIONS

It is apparent that for successful islet engraftment and tolerance induction, there is a dire need for novel immunotherapies that can decrease innate immune-derived signals and mitigate adaptive immune responses involved in graft rejection. Our results demonstrate the feasibility of (PVPON/TA) nanothin coatings to mediate immunosuppression by blunting inflammatory chemokine expression, T cell trafficking, pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage differentiation, and maintaining in vivo islet function. These results are significant since therapies that show promise in diminishing T cell recruitment are lacking and novel (PVPON/TA) nanothin coatings demonstrate potential as another strategy for immunosuppression. Future studies will determine the efficacy of (PVPON/TA) multilayer-encapsulated islets to prevent autoimmune diabetes in mouse models of allo- and xenotransplantation. We anticipate that islet encapsulation with (PVPON/TA) multilayers will have a profound immunomodulatory effect on allo- and xenoreactive immune cells, prevent pancreatic β-cell destruction, and restore euglycemia.

Supplementary Material

Macrophages were gated using FSC/SSC profiles (A). Single cells were identified by FSC-height and FSC-area (B). Representative live cells were gated using a fixable live-dead stain and SSC (C). Dead cells were excluded utilizing a fixable live-dead stain and is shown as heat-killed cells for 20 minutes (D). F4/80+ macrophages were identified by F4/80 expression and SSC (E).

Cxcl10 mRNA accumulation (A) and CXCL10 expression (B) from (PVPON/TA)-treated bone marrow-derived macrophages was examined by qRT-PCR and ELISA, respectively, after 48-hour stimulation with 25μg/mL of p(I:C). Results were normalized to Emr1 and the unstimulated samples were set to 1 and used as the calibrator control. Supernatant of (PVPON/TA)-treated bone marrow-derived macrophages stimulated at 25μg/mL of p(I:C) was examined via ELISA. Graphed data are representative of 3 independent experiments done in at least triplicates. ns, not significant; ***p<0.0001; **p<0.01.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ashley Burg and Dr. Ruth McDowell for critical reading of the manuscript.

The abbreviations used are

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- T1D

Type 1 diabetes

- MTT

thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide

- NOD

Non-Obese Diabetic

- TA

tannic acid

- PVPON

poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone)

- DMPO

5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide

- FSC

forward scatter

- SSC

side scatter

Footnotes

This work was supported by an NIH/NIDDK R01 award (DK099550) (HMT), American Diabetes Association Career Development Award (7-12-CD-11) (HMT), Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Award (1-SRA-2015-42-A-N) (HMT), NIH NIAID (5T32AI007051-35) Immunologic Diseases and Basic Immunology T32 training grant (LEP), and an NSF-DMR Award 1306110 (EK). The following core facilities were used to generate data for the manuscript: Animal Resources Program (G20RR025858, Sam Cartner, DVM, PhD) and the Comprehensive Arthritis, Musculoskeletal, and Autoimmunity Center: Epitope Recognition Immunoreagent Core (P30 AR48311, Mary Ann Accavitti-Loper, PhD).

References

- 1.C. Emerging Risk Factors. Seshasai SR, Kaptoge S, Thompson A, DiAngelantonio E, Gao P, Sarwar N, Whincup PH, Mukamal KJ, Gillum RF, Holme I, Njolstad I, Fletcher A, Nilsson P, Lewington S, Collins R, Gudnason V, Thompson SG, Sattar N, Selvin E, Hu FB, Danesh J. Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(9):829–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro AM, Lakey JR, Ryan EA, Korbutt GS, Toth E, Warnock GL, Kneteman NM, Rajotte RV. Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(4):230–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro AM, Ricordi C, Hering BJ, Auchincloss H, Lindblad R, Robertson RP, Secchi A, Brendel MD, Berney T, Brennan DC, Cagliero E, Alejandro R, Ryan EA, DiMercurio B, Morel P, Polonsky KS, Reems JA, Bretzel RG, Bertuzzi F, Froud T, Kandaswamy R, Sutherland DE, Eisenbarth G, Segal M, Preiksaitis J, Korbutt GS, Barton FB, Viviano L, Seyfert-Margolis V, Bluestone J, Lakey JR. International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(13):1318–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rother KI, Harlan DM. Challenges facing islet transplantation for the treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(7):877–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI23235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tezza S, Ben Nasr M, Vergani A, Valderrama Vasquez A, Maestroni A, Abdi R, Secchi A, Fiorina P. Novel immunological strategies for islet transplantation. Pharmacol Res. 2015;98:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozlovskaya V, Xue B, Lei W, Padgett LE, Tse HM, Kharlampieva E. Hydrogen-bonded multilayers of tannic Acid as mediators of T-cell immunity. Advanced healthcare materials. 2015;4(5):686–94. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201400657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kozlovskaya V, Zavgorodnya O, Chen Y, Ellis K, Tse HM, Cui W, Thompson JA, Kharlampieva E. Ultrathin polymeric coatings based on hydrogen-bonded polyphenol for protection of pancreatic islet cells. Advanced functional materials. 2012;22(16):3389–3398. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201200138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexander JF, Kozlovskaya V, Chen J, Kuncewicz T, Kharlampieva E, Godin B. Cubical Shape Enhances the Interaction of Layer-by-Layer Polymeric Particles with Breast Cancer Cells. Adv Healthc Mater. 2015;4(17):2657–66. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter JL, Drachuk I, Harbaugh S, Kelley-Loughnane N, Stone M, Tsukruk VV. Truly nonionic polymer shells for the encapsulation of living cells. Macromol Biosci. 2011;11(9):1244–53. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201100129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, Kozlovskaya V, Goins A, Campos-Gomez J, Saeed M, Kharlampieva E. Biocompatible shaped particles from dried multilayer polymer capsules. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14(11):3830–41. doi: 10.1021/bm4008666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ejima H, Richardson JJ, Liang K, Best JP, van Koeverden MP, Such GK, Cui J, Caruso F. One-step assembly of coordination complexes for versatile film and particle engineering. Science. 2013;341(6142):154–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1237265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shukla A, Fang JC, Puranam S, Jensen FR, Hammond PT. Hemostatic multilayer coatings. Adv Mater. 2012;24(4):492–6. doi: 10.1002/adma.201103794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhuk I, Jariwala F, Attygalle AB, Wu Y, Libera MR, Sukhishvili SA. Self-defensive layer-by-layer films with bacteria-triggered antibiotic release. ACS nano. 2014;8(8):7733–45. doi: 10.1021/nn500674g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erel-Unal I, Sukhishvili SA. Hydrogen-Bonded Multilayers of a Neutral Polymer and a Polyphenol. Macromolecules. 2008;41(11):3962–3970. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shutava T, Prouty M, Kommireddy D, Lvov Y. pH Responsive Decomposable Layer-by-Layer Nanofilms and Capsules on the Basis of Tannic Acid. Macromolecules. 2005;38(7):2850–2858. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shutava TG, Balkundi SS, Lvov YM. (−)-Epigallocatechin gallate/gelatin layer-by-layer assembled films and microcapsules. Journal of colloid and interface science. 2009;330(2):276–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2008.10.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen GT, Wang CH, Zhang JG, Wang Y, Zhang R, Du FS, Yan N, Kou Y, Li ZC. Toward Functionalization of Thermoresponsive Poly(N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone) Macromolecules. 2010;43:9972–9981. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen TE, Palarasah Y, Skjodt MO, Ogaki R, Benter M, Alei M, Kolmos HJ, Koch C, Kingshott P. Decreased material-activation of the complement system using low-energy plasma polymerized poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) coatings. Biomaterials. 2011;32(20):4481–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forman HJ, Torres M, Fukuto J. Redox signaling. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;234–235(1–2):49–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sareila O, Kelkka T, Pizzolla A, Hultqvist M, Holmdahl R. NOX2 complex-derived ROS as immune regulators. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15(8):2197–208. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lenzen S, Drinkgern J, Tiedge M. Low antioxidant enzyme gene expression in pancreatic islets compared with various other mouse tissues. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20(3):463–6. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)02051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lightfoot YL, Chen J, Mathews CE. Oxidative stress and Beta cell dysfunction. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;900:347–62. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-720-4_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lortz S, Tiedge M, Nachtwey T, Karlsen AE, Nerup J, Lenzen S. Protection of insulin-producing RINm5F cells against cytokine-mediated toxicity through overexpression of antioxidant enzymes. Diabetes. 2000;49(7):1123–30. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.7.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathews CE, Leiter EH. Constitutive differences in antioxidant defense status distinguish alloxan-resistant and alloxan-susceptible mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27(3–4):449–55. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bottino R, Balamurugan AN, Tse H, Thirunavukkarasu C, Ge X, Profozich J, Milton M, Ziegenfuss A, Trucco M, Piganelli JD. Response of human islets to isolation stress and the effect of antioxidant treatment. Diabetes. 2004;53(10):2559–68. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.10.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sklavos MM, Bertera S, Tse HM, Bottino R, He J, Beilke JN, Coulombe MG, Gill RG, Crapo JD, Trucco M, Piganelli JD. Redox modulation protects islets from transplant-related injury. Diabetes. 2010;59(7):1731–8. doi: 10.2337/db09-0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sklavos MM, Tse HM, Piganelli JD. Redox modulation inhibits CD8 T cell effector function. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(10):1477–86. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tse HM, Milton MJ, Schreiner S, Profozich JL, Trucco M, Piganelli JD. Disruption of innate-mediated proinflammatory cytokine and reactive oxygen species third signal leads to antigen-specific hyporesponsiveness. J Immunol. 2007;178(2):908–17. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Padgett LE, Tse HM. NADPH Oxidase-Derived Superoxide Provides a Third Signal for CD4 T Cell Effector Responses. J Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Padgett LE, Burg AR, Lei W, Tse HM. Loss of NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide skews macrophage phenotypes to delay type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64(3):937–46. doi: 10.2337/db14-0929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El Hadri K, Mahmood DF, Couchie D, Jguirim-Souissi I, Genze F, Diderot V, Syrovets T, Lunov O, Simmet T, Rouis M. Thioredoxin-1 promotes anti-inflammatory macrophages of the M2 phenotype and antagonizes atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(6):1445–52. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.249334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandra AP, Ou-Yang L, Wong JK, Ha H, Walters SN, Patel AT, Hawthorne WJ, Yi SN. Association between islet xenograft rejection mediated by activated macrophages and upregulated chemokines. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2007;32(1):26–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corrado A, Ferrari SM, Ferri C, Ferrannini E, Antonelli A, Fallahi P. Type 1 diabetes and (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL) 10 chemokine. La Clinica terapeutica. 2014;165(2):e181–5. doi: 10.7471/CT.2014.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhernakova A, Alizadeh BZ, Eerligh P, Hanifi-Moghaddam P, Schloot NC, Diosdado B, Wijmenga C, Roep BO, Koeleman BP. Genetic variants of RANTES are associated with serum RANTES level and protection for type 1 diabetes. Genes Immun. 2006;7(7):544–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu F, Kozlovskaya V, Zavgorodnya O, Martinez-Lopez C, Catledge S, Kharlampieva E. Encapsulation of anticancer drug by hydrogen-bonded multilayers of tannic acid. Soft Matter. 2014;10(46):9237–47. doi: 10.1039/c4sm01813c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zavgorodnya O, Kozlovskaya V, Liang X, Kothalawala N, Catledge SA, Dass A, Kharlampieva E. Temperature-responsive properties of poly(N- vinylcaprolactam) multilayer hydrogels in the presence of Hofmeister anions. Materials Research Express. 2014;1(035039) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tse HM, Josephy SI, Chan ED, Fouts D, Cooper AM. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway is instrumental in determining the ability of Mycobacterium avium to grow in murine macrophages. J Immunol. 2002;168(2):825–33. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seleme MC, Lei W, Burg AR, Goh KY, Metz A, Steele C, Tse HM. Dysregulated TLR3-dependent signaling and innate immune activation in superoxide-deficient macrophages from nonobese diabetic mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(9):2047–56. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramirez DC, Mason RP. Immuno-spin trapping: detection of protein-centered radicals. In: Current protocols in toxicology; Mahin D, editor. Maines Chapter 17. 2005. Unit 17 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mason RP. Using anti-5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (anti-DMPO) to detect protein radicals in time and space with immuno-spin trapping. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36(10):1214–23. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.02.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Padgett LE, Anderson B, Liu C, Ganini D, Mason RP, Piganelli JD, Mathews CE, Tse HM. Loss of NOX-Derived Superoxide Exacerbates Diabetogenic CD4 T-Cell Effector Responses in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64(12):4171–83. doi: 10.2337/db15-0546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tse HM, Milton MJ, Piganelli JD. Mechanistic analysis of the immunomodulatory effects of a catalytic antioxidant on antigen-presenting cells: implication for their use in targeting oxidation-reduction reactions in innate immunity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36(2):233–47. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dufour JM, Rajotte RV, Zimmerman M, Rezania A, Kin T, Dixon DE, Korbutt GS. Development of an ectopic site for islet transplantation, using biodegradable scaffolds. Tissue engineering. 2005;11(9–10):1323–31. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tse HM, Thayer TC, Steele C, Cuda CM, Morel L, Piganelli JD, Mathews CE. NADPH oxidase deficiency regulates Th lineage commitment and modulates autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2010;185(9):5247–58. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bradley BJ, Wang YY, Lafferty KJ, Haskins K. In vivo activity of an islet-reactive T-cell clone. J Autoimmun. 1990;3(4):449–56. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(05)80012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dallas-Pedretti A, McDuffie M, Haskins K. A diabetes-associated T-cell autoantigen maps to a telomeric locus on mouse chromosome 6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(5):1386–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker MS, Chen X, Rotramel AR, Nelson JJ, Lu B, Gerard C, Kanwar Y, Kaufman DB. Genetic deletion of chemokine receptor CXCR3 or antibody blockade of its ligand IP-10 modulates posttransplantation graft-site lymphocytic infiltrates and prolongs functional graft survival in pancreatic islet allograft recipients. Surgery. 2003;134(2):126–33. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Solomon MF, Kuziel WA, Mann DA, Simeonovic CJ. The role of chemokines and their receptors in the rejection of pig islet tissue xenografts. Xenotransplantation. 2003;10(2):164–77. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2003.01146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uppaluri R, Sheehan KC, Wang L, Bui JD, Brotman JJ, Lu B, Gerard C, Hancock WW, Schreiber RD. Prolongation of cardiac and islet allograft survival by a blocking hamster anti-mouse CXCR3 monoclonal antibody. Transplantation. 2008;86(1):137–47. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31817b8e4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lasch S, Muller P, Bayer M, Pfeilschifter JM, Luster AD, Hintermann E, Christen U. Anti-CD3/Anti-CXCL10 Antibody Combination Therapy Induces a Persistent Remission of Type 1 Diabetes in Two Mouse Models. Diabetes. 2015;64(12):4198–211. doi: 10.2337/db15-0479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coppieters KT, Amirian N, Pagni PP, Baca Jones C, Wiberg A, Lasch S, Hintermann E, Christen U, von Herrath MG. Functional redundancy of CXCR3/CXCL10 signaling in the recruitment of diabetogenic cytotoxic T lymphocytes to pancreatic islets in a virally induced autoimmune diabetes model. Diabetes. 2013;62(7):2492–9. doi: 10.2337/db12-1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarkar SA, Lee CE, Victorino F, Nguyen TT, Walters JA, Burrack A, Eberlein J, Hildemann SK, Homann D. Expression and regulation of chemokines in murine and human type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2012;61(2):436–46. doi: 10.2337/db11-0853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(1):23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martinez FO, Helming L, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:451–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Delmastro MM, Piganelli JD. Oxidative stress and redox modulation potential in type 1 diabetes. Clin Dev Immunol. 2011;2011:593863. doi: 10.1155/2011/593863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eckhardt A, Harorli T, Limtanyakul J, Hiller KA, Bosl C, Bolay C, Reichl FX, Schmalz G, Schweikl H. Inhibition of cytokine and surface antigen expression in LPS-stimulated murine macrophages by triethylene glycol dimethacrylate. Biomaterials. 2009;30(9):1665–74. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lefeuvre M, Amjaad W, Goldberg M, Stanislawski L. TEGDMA induces mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress in human gingival fibroblasts. Biomaterials. 2005;26(25):5130–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Volk J, Leyhausen G, Geurtsen W. Glutathione level and genotoxicity in human oral keratinocytes exposed to TEGDMA. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2012;100(2):391–9. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shah D, Wanchu A, Bhatnagar A. Interaction between oxidative stress and chemokines: possible pathogenic role in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Immunobiology. 2011;216(9):1010–7. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hiura TS, Kempiak SJ, Nel AE. Activation of the human RANTES gene promoter in a macrophage cell line by lipopolysaccharide is dependent on stress-activated protein kinases and the IkappaB kinase cascade: implications for exacerbation of allergic inflammation by environmental pollutants. Clin Immunol. 1999;90(3):287–301. doi: 10.1006/clim.1998.4659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.MacGregor HJ, Kato Y, Marshall LJ, Nevell TG, Shute JK. A copper-hydrogen peroxide redox system induces dityrosine cross-links and chemokine oligomerisation. Cytokine. 2011;56(3):669–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blau JE, Abegg MR, Flegel WA, Zhao X, Harlan DM, Rother KI. Long-term immunosuppression after solitary islet transplantation is associated with preserved C-peptide secretion for more than a decade. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(11):2995–3001. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bottino R, Trucco M. Clinical implementation of islet transplantation: A current assessment. Pediatr Diabetes. 2015;16(6):393–401. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu C, Noorchashm H, Sutter JA, Naji M, Prak EL, Boyer J, Green T, Rickels MR, Tomaszewski JE, Koeberlein B, Wang Z, Paessler ME, Velidedeoglu E, Rostami SY, Yu M, Barker CF, Naji A. B lymphocyte-directed immunotherapy promotes long-term islet allograft survival in nonhuman primates. Nat Med. 2007;13(11):1295–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Macrophages were gated using FSC/SSC profiles (A). Single cells were identified by FSC-height and FSC-area (B). Representative live cells were gated using a fixable live-dead stain and SSC (C). Dead cells were excluded utilizing a fixable live-dead stain and is shown as heat-killed cells for 20 minutes (D). F4/80+ macrophages were identified by F4/80 expression and SSC (E).

Cxcl10 mRNA accumulation (A) and CXCL10 expression (B) from (PVPON/TA)-treated bone marrow-derived macrophages was examined by qRT-PCR and ELISA, respectively, after 48-hour stimulation with 25μg/mL of p(I:C). Results were normalized to Emr1 and the unstimulated samples were set to 1 and used as the calibrator control. Supernatant of (PVPON/TA)-treated bone marrow-derived macrophages stimulated at 25μg/mL of p(I:C) was examined via ELISA. Graphed data are representative of 3 independent experiments done in at least triplicates. ns, not significant; ***p<0.0001; **p<0.01.