Abstract

Effector memory T lymphocytes (TEM cells) that lack expression of CCR7 are major drivers of inflammation in a number of autoimmune diseases, including multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. The Kv1.3 potassium channel is a key regulator of CCR7− TEM cell activation. Blocking Kv1.3 inhibits TEM cell activation and attenuates inflammation in autoimmunity, and as such, Kv1.3 has emerged as a promising target for the treatment of TEM cell-mediated autoimmune diseases. The scorpion venom-derived peptide HsTX1 and its analog HsTX1[R14A] are potent Kv1.3 blockers and HsTX1[R14A] is selective for Kv1.3 over closely-related Kv1 channels. PEGylation of HsTX1[R14A] to create a Kv1.3 blocker with a long circulating half-life reduced its affinity but not its selectivity for Kv1.3, dramatically reduced its adsorption to inert surfaces, and enhanced its circulating half-life in rats. PEG-HsTX1[R14A] is equipotent to HsTX1[R14A] in preferential inhibition of human and rat CCR7− TEM cell proliferation, leaving CCR7+ naïve and central memory T cells able to proliferate. It reduced inflammation in an active delayed-type hypersensitivity model and in the pristane-induced arthritis (PIA) model of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Importantly, a single subcutaneous dose of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] reduced inflammation in PIA for a longer period of time than the non-PEGylated HsTX1[R14A]. Together, these data indicate that HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] are effective in a model of RA and are therefore potential therapeutics for TEM cell-mediated autoimmune diseases. PEG-HsTX1[R14A] has the additional advantages of reduced non-specific adsorption to inert surfaces and enhanced circulating half-life.

Keywords: immunomodulation, effector memory T lymphocyte, voltage-gated channel, KCNA3, PEGylated Kv1.3 blocker, disulfide rich peptide

1. Introduction

According to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, more than 80 autoimmune diseases have been described, affecting approximately 50 million Americans. T lymphocytes are major players in many autoimmune diseases. In humans, T lymphocytes can be separated into three populations based on the expression of the phosphatase CD45RA and the chemokine receptor CCR7 [1]: naïve T cells are CD45RA+CCR7+, central memory T (TCM) cells are CD45RA−CCR7+ and effector memory T (TEM) cells are CD45RA−CCR7−. T lymphocytes associated with autoimmune diseases and other chronic inflammatory diseases are mainly CCR7− TEM cells [2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; 10]. In mice, the deletion of CCR7 induces multi-organ autoimmunity [11]. CCR7− TEM lymphocytes therefore represent attractive targets for the treatment of autoimmune diseases.

Following activation with antigens or mitogens, human CCR7− TEM cells differ from CCR7+ naïve and TCM cells by the upregulation of voltage-gated Kv1.3 potassium channels [2; 3; 7; 12]. Kv1.3 blockade in CCR7− TEM lymphocytes alters calcium homeostasis and leads to inhibition of proliferation and cytokine secretion [13; 14; 15]. In contrast, CCR7+ naïve and TCM cells can escape Kv1.3 block as they rely on a different potassium channel for their activation and function. This phenotype is recapitulated by rat, but not mouse, T lymphocytes [16; 17]. Kv1.3 channels have therefore been proposed as a therapeutic target in various autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, asthma, ulcerative colitis, type 1 diabetes mellitus, obesity, alopecia areata, glomerulonephritis, and psoriasis [2; 3; 18; 19; 20; 21; 22; 23]. Indeed, autoantigen-specific T cells and T cells at sites of inflammation during chronic inflammatory diseases express high levels of Kv1.3 [2; 3; 7; 8; 20; 23; 24].

Blocking Kv1.3 has proven effective in reducing disease severity in rat models of TEM lymphocyte-mediated delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) and chronic inflammatory diseases without preventing the clearance of acute infections [2; 3; 18; 25; 26; 27; 28; 29]. The peptide Kv1.3 blocker Dalazatide (ShK-186) [13; 15; 30], a synthetic analog of the sea anemone venom peptide ShK, has been shown in Phase 1a and 1b clinical trials to be well-tolerated and reduce the severity of target lesions in active plaque psoriasis [31]. These studies indicate the potential of Kv1.3 blockers to be valuable therapeutic options for a multitude of diseases. However, their relatively short circulating half-lives require the generation of selective and potent Kv1.3 blockers with long circulating half-lives.

HsTX1 is a 34-residue peptide from the of the scorpion Heterometrus spinnifer. It has four disulfide bonds, is C-terminally amidated, and is a potent blocker of Kv1 channels [32; 33; 34; 35]. We have generated an HsTX1 analog by substituting arginine 14 with alanine [33]. The resulting HsTX1[R14A] exhibits a 2,000-fold selectivity for Kv1.3 over the related Kv1.1 channel. Selectivity of Kv1.3 over Kv1.1 and other related channels is considered a benchmark standard for potential Kv1.3 blocker-based therapeutics for the treatment of autoimmunity [13; 15] and the high selectivity of HsTX1[R14A] for Kv1.3 makes it a potential therapeutic for chronic inflammatory diseases. HsTX1[R14A] has also been shown to be systemically deliverable through the pulmonary and buccal mucosal routes [36; 37], making this peptide attractive in a clinical setting.

The addition of large polyethylene glycol (PEG) moieties to small molecules, peptides, and other therapeutics is a widely used method to improve their pharmaceutical properties. In particular, PEGylation increases the circulating half-life of therapeutics by increasing hydrophilicity through hydrogen bonding, resulting in reduced serum protein binding, and by reducing renal clearance, thereby reducing the frequency of treatment and reducing the risk of toxicity [38; 39]. It can also reduce a peptide’s immunogenicity and protect it from proteolysis and non-specific adsorption to inert surfaces, making PEGylation a valuable tool to improve a compound’s properties as a therapeutic [38]. Here, we PEGylated HsTX1[R14A] and tested its functionality and selectivity for blocking Kv1.3, as well as determining its effectiveness for inhibiting TEM cell proliferation. Finally, we tested its efficacy in reducing inflammation in two animal models of TEM cell-mediated inflammation; delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) and pristane-induced arthritis (PIA), a model of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Peptide synthesis

HsTX1[R14A] was synthesized and folded as previously described [33]. Selective conjugation was directed to the N-terminus of the HSTX1[R14A] via reductive alkylation with an activated 30 kD monomethoxy-PEG-aldehyde, similar to methods used to make N-terminally PEGylated ShK [40]. The conjugation reaction was performed at a concentration of 2 mg/mL in 50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 4.5, with a two-fold excess of 30 kD-monomethoxy-PEG-aldehyde (NOF Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan). After 30 min reaction time, sodium cyanoborohydride (NaCNBH3) was added to make the total concentration 20 mM. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 48 h with analytical samples removed to track the reaction progress. The completed reaction was quenched with a 10-fold dilution with 20 mM sodium acetate (NaOAc), pH 4. The conjugated peptide was subsequently purified by preparative RP-HPLC using Phenomenex Luna C18-silica (10 μm) using a linear gradient of 0.05% TFA in H2O versus acetonitrile. The PEGylated product eluted at 52% acetonitrile, compared with the free peptide, which eluted at 28.5%; free PEG-aldehyde eluted at 58% acetonitrile. The monomethoxy-PEG-HsTX1[R14A] was characterized by Applied Biosystems Voyager MALDI-ToF mass spectroscopy using alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid as a matrix. Lyophilized HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] were dissolved in P6N buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, 0.8% NaCl, and 0.05% polysorbate 20, pH 6.0) [26] to make stock solutions of 1 and 10 mg/mL, respectively, and stored at −20°C.

2.2 Patch clamp electrophysiology

We use the IUPHAR nomenclature to name all ion channels throughout this article [41]. L929 cells stably expressing mKv1.1 and mKv1.3 channels [42], B82 cells stably expressing rKv1.2 channels [42], and MEL cells stably transfected with hKv1.5 channels [42] were a gift from Dr. Chandy (Nanyang Technological University, Singapore). LTK cells stably expressing hKv1.4 channels [43] were obtained from Dr. Tamkun (University of Colorado, Boulder). They were maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 4 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 500 μg/mL G418 [44] (Calbiochem/EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Patch clamp assays were conducted at room temperature (23–25°C) in the whole cell configuration using a Port-a-Patch system (Nanion, Livingston, NJ) or a manual rig, both connected to a HEKA EPC10-USB amplifier controlled with the PatchMaster software [33; 45; 46; 47]. The resistance of pipettes or chips was 2–3 MΩ and the holding potential set to −80 mV. L929 and B82 cells were plated into sterile glass chambers and allowed to adhere. Kv1.5 expression was induced by the addition of 2% DMSO to the culture media of MEL cells for 48 h, after which the cells were plated into poly-L-lysine coated glass chambers. Kv1.x currents were elicited by 200 ms pulses from −80 to 40 mV applied every 30 s. Series resistance compensation of 80% was used when current exceeded 2 nA. The external solution contained 160 mM NaCl, 4.5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Hepes; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH and osmolarity ranged from 290 to 320 mOsm. The internal solution contained 145 mM KF, 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM EGTA, and 2 mM MgCl2; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with KOH and osmolarity ranged from 290 to 320 mOsm. The stocks of HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] were diluted to the indicated concentrations in external solution immediately before application to the cells unless otherwise stated. IC50 values for current block were calculated by fitting the Hill equation to the reduction of peak current at 40 mV.

2.3 Animals

All experiments involving rats were performed under protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Baylor College of Medicine. Female 8–9 week old Dark Agouti (DA) rats (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) and Lewis rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were housed in autoclaved cages and given food and water ad libitum within a facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Rats were euthanized after deep anesthesia with pharmaceutical-grade isoflurane by cardiac perfusion with saline followed by decapitation.

2.4 Primary cells

Spleens collected from healthy Lewis rats were used to prepare single-cell suspensions followed by splenocyte enrichment with Histopaque-1077 gradients. Lewis rat-derived ovalbumin-specific TEM lymphocytes (CCR7− CD45RC−) [48] were provided by Dr. Flügel (University Medical Center Göttingen, Germany) and were maintained by cycles of antigen-induced activation and expansion in cytokine-rich medium. Basic medium contained RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 4 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1% nonessential amino acids, 1% RPMI vitamins, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM Hepes, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin [25]. For antigen activation of TEM cells, basic medium was supplemented with 1% Lewis rat serum; irradiated (30 Gy) thymocytes from Lewis rats, loaded with 10 μg/mL ovalbumin, were used as antigen-presenting cells. For cytokine-dependent expansion of the TEM cells, basic medium was supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 10% T cell growth factor [49].

Peripheral blood was collected from healthy volunteers (Table 1) in sterile sodium heparin-coated vacutainer tubes under a protocol approved by Baylor College of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board. Mononuclear cells were separated with a Histopaque-1077 gradient. They were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated FBS, 4 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1% nonessential amino acids, 1% RPMI vitamins, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM Hepes, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin.

Table 1.

Characteristics of peripheral blood donors.

| Subject | Gender | Age | Race |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 22 | Caucasian |

| 2 | Female | 54 | Caucasian |

| 3 | Male | 21 | Mexican-American |

| 4 | Female | 34 | Mexican-American |

| 5 | Male | 47 | African-American |

| 6 | Male | 30 | Caucasian |

2.5 Proliferation of rat splenocytes and TEM cells

Lewis rat splenocyte and ovalbumin-specific TEM lymphocyte proliferation in the presence or absence of HsTX1[R14A] or PEG-HsTX1[R14A] was determined by [3H] thymidine incorporation, as described [25; 50]. Either 105 splenocytes or 50,000 TEM cells were placed in each well of a 96-well plate and incubated with an HsTX1 analog for 30 min. The splenocytes or TEM cells were then stimulated with 1 μg/mL concanavalin A or 10 μg/mL ovalbumin + 2 × 106 irradiated antigen-presenting cells, respectively, for 72 h. [3H] thymidine was added to the cells for the last 16–18 h of stimulation. DNA was harvested on glass filters and the incorporated [3H] thymidine was quantified by a β-scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter).

2.6 Proliferation of human CCR7− TEM and CCR7+ naïve/TCM cells

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were loaded with the cell division tracer CellTrace Violet following the manufacturer’s instructions (5 μM; Molecular Probes/ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). After washes, they were resuspended at 106/mL and seeded into U-bottom 96-well plates, 100 μl/well (Corning/ThermoFisher Scientific) in medium + 5% FBS. They were left resting or were activated with anti-CD3 antibodies (clone OKT3, 1 ng/mL, eBioscience/ThermoFisher Scientific; Antibody registry: RRID AB_468855) for 7 days in medium + 5% FBS. HsTX1[R14A] (100 nM) or PEG-HsTX1[R14A] (250 nM) were added to the cells 30 min before addition of the activating anti-CD3 antibodies. After 7 days, T lymphocytes were detected by staining with a phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD3 antibody (0.6 μg/tube, BioLegend, Pacific Heights, CA; catalog # 300441) and CCR7− TEM cells were distinguished from CCR7+ naïve and central memory T cells by staining with an Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated antibody against CCR7 (1 0μg/tube, BioLegend; catalog # 353218). The percentage of divided CCR7+ and CCR7− T cells was determined to be the percentage of T cells with a lower CellTrace Violet fluorescence compared to that of the unstimulated, resting CCR7+ and CCR7− T cells. Data were acquired with a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR).

2.7 Pharmacokinetics of PEG-HsTX1[R14A]

Lewis rats received a single subcutaneous injection in the scruff of the neck (500 μL/rat) of vehicle alone (P6N buffer: 10 mM sodium phosphate, 0.8% NaCl, and 0.05% polysorbate 20, pH 6.0) or of 1 mg/kg PEG-HsTX1[R14A]. Serum was collected as described [51] at varying times following the PEG-HsTX1[R14A] injection. The amount of circulating PEG-HsTX1[R14A] was quantified using a PEGylated protein ELISA kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Enzo Life Sciences) and as described [50]. The circulating half-life was determined by fitting the serum PEG concentrations to a single exponential decay.

2.8 Delayed-type hypersensitivity

Active delayed-type hypersensitivity assays were conducted as described [26; 52]. Lewis rats were immunized with 200 μL of a 1:1 emulsion of 2 mg/mL ovalbumin (Sigma) and complete Freund’s adjuvant (Difco/Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) via subcutaneous injection in the flanks. Rats were challenged 7 days later by a subcutaneous injection of 20 μg ovalbumin in saline in the pinna of one ear and with saline in the other ear under isoflurane anesthesia. Ear inflammation was measured 24 h later using a PK-0505 micrometer (Mitutoyo, Melville, NY) [53]. Changes in ear thickness were determined by comparing the thickness of the ovalbumin-challenged ear to the vehicle-challenged ear of each rat. Rats were either pretreated 7 days prior to immunization, at the time of immunization, or at the time of challenge with 0.1 mg/kg HsTX1[R14A] or 1 mg/kg PEG-HsTX1[R14A]. As with the pharmacokinetics, P6N buffer was used as a vehicle control.

2.9 Pristane-induced arthritis induction and scoring

Pristane-induced arthritis was induced and monitored as described [2; 26; 54]. PIA was induced in DA rats by the subcutaneous injection of 150 μl of pristane (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) at the base of the tail under isoflurane anesthesia. A clinical score was determined daily for each animal by adding 5 points for each swollen wrist or ankle and 1 point for each swollen toe joint, for a maximum score of 60 per rat. Upon disease onset, as defined by having at least one swollen joint, rats were assigned to receive a subcutaneous treatment of vehicle (P6N buffer) once weekly, 0.1 mg/kg HsTX1[R14A] once weekly or every other day, 1 mg/kg PEG-HsTX1[R14A] once weekly, or a single dose of either 0.1 mg/kg HsTX1[R14A] or 15 mg/kg PEG-HsTX1[R14A]. All rats were monitored daily for 21 days after disease onset. Since early onset often correlates with higher disease severity, animals were assigned to different groups at arthritis onset to avoid bias due to this variable. The first animal with clinical signs was assigned to group A, the second to group B, and so forth until each group had one animal. A similar strategy was used to assign the second rat to each group and the randomization was continued until all groups were filled. Animals that had not developed clinical signs of disease 18 days after injection of pristane were removed from the trials.

2.10 Joint X-rays and histology

Following euthanasia, paws from healthy rats and rats with PIA were collected and X-rays were completed using an In-Vivo Xtreme imaging system (Bruker) or fixed in formalin, decalcified, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or safranin O/fast green, as described [2; 54]. Histology photos were taken at 10× magnification using a BX41 upright microscope equipped with a QImaging QICAM Fast1394 camera and the QCapture Pro software v6.0.0.412 (Olympus, Waltham, MA).

2.11 Blood chemistry

At the end of each PIA trial, blood was drawn from the rats by terminal cardiac puncture. Serum was immediately collected and frozen at −80°C. Serum samples from 5 randomly selected rats in each group were analyzed from a whole blood chemistry panel within the Center for Comparative Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine by pathologists blinded to the treatment conditions.

2.12 Statistical analysis

Data are shown as mean ± SEM. All data were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U tests or one-way ANOVA, except for the PIA clinical scores, which were assessed using the Friedman test to compared scores at the completion of the experiment and Mann-Whitney U tests to compare scores between groups on individual days (GraphPad Prism 5).

3. Results

3.1 PEG-HsTX[R14A] blocks Kv1.3 potassium channels

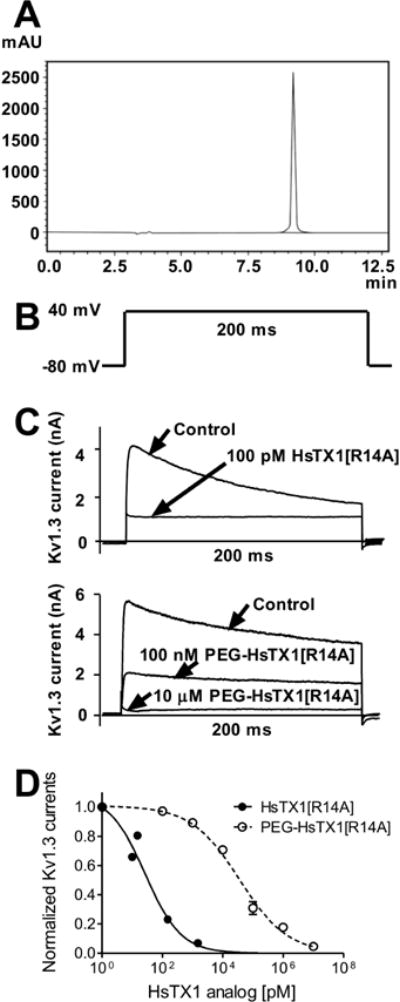

Reverse-phase HPLC analysis of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] showed a single symmetrical peak, demonstrating high purity of the compound (Fig. 1A). Neither free 30kD monomethoxy-Peg30kD aldehyde nor unreacted HsTX1[R14A] was observed in the chromatogram.

Fig. 1.

Purity of and effectiveness of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] in blocking Kv1.3 channels.

(A) Reverse phase HPLC chromatogram of purified 30 kD PEG-HsTX1[R14A] on an ODS silica using a gradient from 30–60% B in 30 min at 1 ml/min monitoring at 220 nm. A = 0.05% TFA in H2O and B = 0.05% TFA in acetonitrile. (B) Pulse protocol used to elicit Kv1.3 currents in L-929 fibroblasts stably expressing the channel. (C) Representative whole-cell Kv1.3 currents measured by patch-clamp in cells stably expressing Kv1.3 before (control) and after application of 100 pM HsTX1[R14A] (top) or 100 nM and 10 μM PEG-HsTX1[R14A]. (D) Dose-dependent response of HsTX1[R14A] (●) and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] (○ and dashed line) on Kv1.3 currents fitted to a Hill equation (N = 3 cells per concentration).

HsTX1[R14] is a Kv1.3 channel blocker [33]. Since modification of a peptide channel blocker can dramatically alter its ability to block the target channel, we tested the ability of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] to block Kv1.3 currents. We first verified that HsTX1[R14] blocks the Kv1.3 channel with an IC50 of 27 ± 9 pM (Fig. 1B–D). The peptide PEGylated on its N-terminus also blocked Kv1.3, albeit with an IC50 of 35.9 ± 6.3 nM; displaying a 1,300-fold loss in affinity for Kv1.3 (Fig. 1B–D).

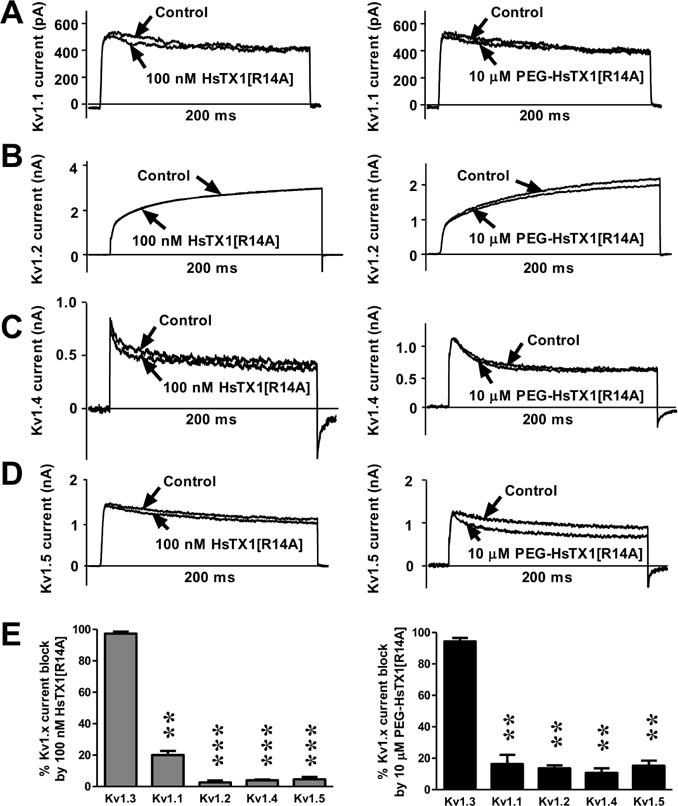

3.2 PEGylation of HsTX1[R14A] does not alter its selectivity profile for Kv1.3 over other Kv1 channels

We verified that PEGylation of HsTX1[R14A] does not reduce its selectivity for Kv1.3 through whole-cell patch clamp on cells stably expressing Kv1.1, Kv1.2, Kv1.3, Kv1.4, or Kv1.5. We tested 100 nM of HsTX1[R14A] and 10 μM PEG-HsTX1[R14A], concentrations chosen for their ability to block 90–100% of Kv1.3 currents. They did not significantly reduce the potassium currents of cells expressing Kv1.1, Kv1.2, Kv1.4, or Kv1.5 with a maximum block of 20% or less of these currents (Fig. 2). HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] therefore displayed more than a 250-fold selectivity for Kv1.3 over all other Kv1 channels tested.

Fig. 2.

HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] are selective for Kv1.3 over closely related Kv1 channels.

(A–D) Whole-cell Kv1.1 (A), Kv1.2 (B), Kv1.4 (C), and Kv1.5 (D) currents measured by patch-clamp in stably transfected cells before (control) and after perfusion of 100 nM HsTX1[R14A] (left panels) or 10 μM PEG-HsTX1[R14A] (right panels). (E) Percentage of Kv1.1–1.5 current block by 100 nM HsTX1[R14A] (left) and by 10 μM PEG-HsTX1[R14A] (right); N = 3 cells per concentration. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, by one-way ANOVA.

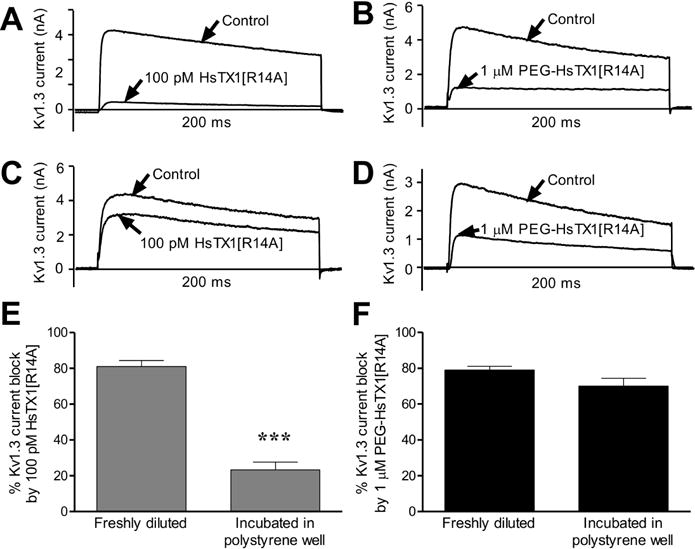

3.3 HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] preferentially reduce TEM lymphocyte proliferation

We have previously demonstrated that HsTX1[R14A], like other selective Kv1.3 blockers, reduces the proliferation of rat TEM cells while having no effect on the proliferation of rat splenocytes, which contain naïve and TCM cells that do not depend on Kv1.3 for their activation [33]. In order to determine if PEGylation affected this characteristic of HsTX1[R14A], we stimulated rat ovalbumin-specific TEM cells or rat splenocytes with ovalbumin-loaded irradiated thymocytes or concanavalin A, respectively, in the presence of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] or HsTX1[R14A] and measured proliferation by [3H] thymidine incorporation. Both HsTX1[R14A] and its PEGylated analog inhibited the proliferation of the rat TEM cells with IC50s of ~ 100 nM and ~250 nM, respectively. Neither had any effect on the proliferation of splenocytes (Fig. 3A, B).

Fig. 3.

PEG-HsTX1[R14A] and HsTX1[R14A] preferentially inhibit TEM cell proliferation.

(A) Lewis rat ovalbumin-specific TEM cell proliferation stimulated by ovalbumin and irradiated antigen-presenting cells in the presence or absence of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] (black) or HsTX1[R14A] (grey); mean ± SEM; n = 6). (B) Rat splenocyte proliferation stimulated with concanavalin A (con A) in the presence or absence of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] (black) or HsTX1[R14A] (grey). (C and D) Left, representative flow cytometric plots of CellTrace Violet dye dilution and CCR7 expression of CD3+ cells from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated for 7 days with or without (C) HsTX1[R14A] or (D) PEG-HsTX1[R14A]. Right, quantification of divided CCR7+ and CCR7− T cells, as determined by gating on CD3+ cells; N = 4; mean ± SEM; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 by one-way ANOVA.

We next used the cell division tracking dye CellTrace Violet and flow cytometry to assess the effects of 250 nM PEG-HsTX1[R14A] and 100 nM HsTX1[R14A] on the proliferation of human CCR7− TEM cells and of human CCR7+ naïve and TCM cells. Both PEG-HsTX1[R14A] and HsTX1[R14A] reduced the proliferation of anti-CD3 antibody-activated CCR7− TEM cells by approximately half. In contrast, they did not significantly reduce the proliferation of CCR7+ T cells (Fig. 3C, D). This indicates that both HsTX1 analogs selectively inhibit human CCR7− TEM cells, while leaving human naïve and TCM cells able to proliferate.

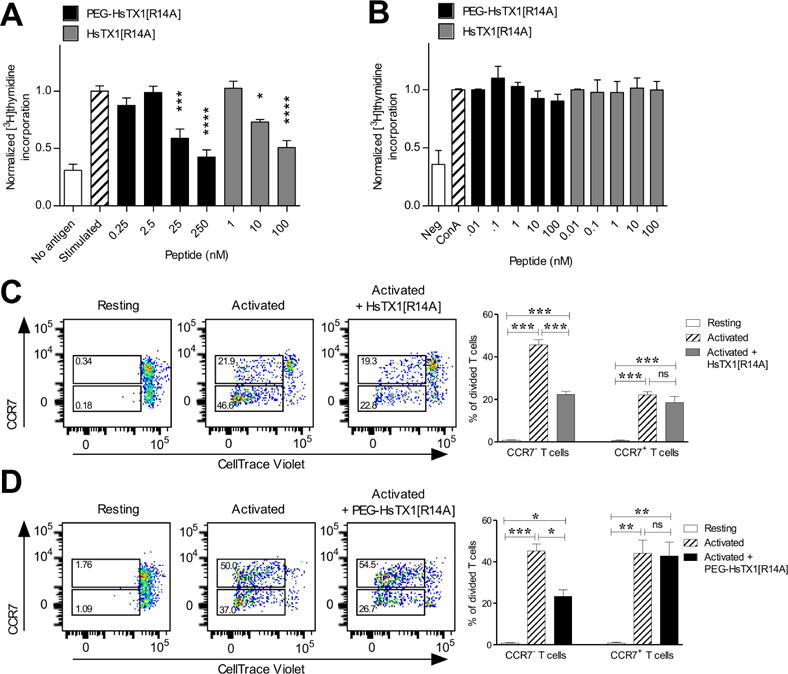

3.4 PEGylation of HsTX1[R14A] reduces its adsorption to polystyrene surfaces

Our electrophysiology data showed a 1,300-fold loss of affinity for Kv1.3 after PEGylation of HsTX1[R14A]. In contrast, both peptides inhibited the proliferation of human and rat TEM cells with similar potencies. Toxin-derived peptides are prone to adsorption onto plastics, such as polystyrene in tissue culture microplates, and PEGylation of peptides and proteins can significantly reduce their adsorption [55; 56; 57; 58]. We therefore tested whether a 24-h incubation of HsTX1[R14A] or PEG-HsTX1[R14A] at room temperature in a tissue culture microplate affected peptide recovery, assessed by its ability to block Kv1.3 channels. A 100 pM concentration of HsTX1[R14A] prepared immediately before perfusion onto the cells induced an approximately 70% reduction in Kv1.3 currents (Fig. 4A). In sharp contrast, pre-incubation of the peptide for 24 h reduced this block to only ~30% (Fig. 4C, E), showing a loss of HsTX1[R14A] by incubation in the polystyrene wells. Incubation of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] for 24 h in the same microplate did not significantly affect its ability to block Kv1.3 channels, suggesting a much higher recovery of the peptide following PEGylation (Fig. 4B, D, F).

Fig. 4.

PEGylation of HsTX1[R14A] reduces its adsorption to polystyrene.

(A–D) Representative whole-cell Kv1.3 currents measured by patch-clamp in cells stably expressing Kv1.3 before (control) and after application of 100 pM HsTX1[R14A] (A, C) or 1 μM PEG-HsTX1[R14A] (B, D). HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] were perfused onto the cells either immediately after dilution (A, B) or were incubated in polystyrene microplates for 24 h before perfusion (C, D). (E, F) Percentage of Kv1.3 current block by 100 pM HsTX1[R14A] (E) and by 1 μM PEG-HsTX1[R14A] (F); N = 3 cells per concentration. ***p<0.001, by non-parametric T-test.

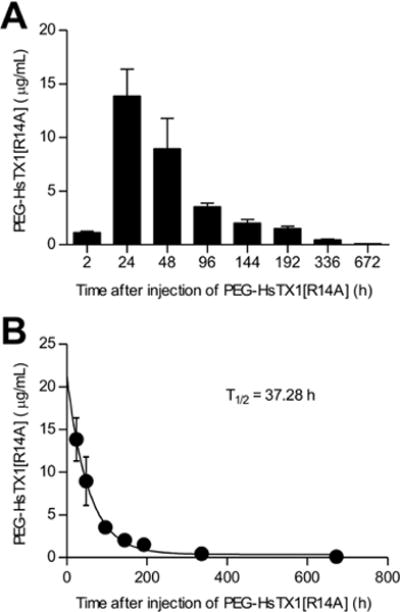

3.5 PEG-HsTX1[R14A] remains at detectable levels in the circulation for two weeks after a single subcutaneous injection

Previously described peptide Kv1.3 blockers have a circulating half-life of less than one hour in rats following subcutaneous injection [16; 59; 60]. We sought to determine if PEG-HsTX1[R14A] is bioavailable following subcutaneous administration and calculate its circulating half-life, taking advantage of the availability of anti-PEG antibodies to detect PEG-HsTX1[R14A] in rat serum by ELISA. Lewis rats received a single subcutaneous injection of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] and serum was serially collected for 672 h (28 days). PEG-HsTX1[R14A] was detectable in serum 2 h after injection and peaked at 24 h after injection with 13.8 ± 2.5 μg/mL, or 400 nM (Fig. 5A), a concentration sufficient to block ~80% of Kv1.3 currents based on our electrophysiology data. Its circulating half-life was 37.3 h (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, PEG-HsTX1[R14A] remained detectable in the serum for up to 336 h (14 days) after injection with a concentration of 0.47 ± 0.06 μg/mL, or 1 nM.

Fig. 5.

Circulating half-life of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] in Lewis rats following a single injection.

(A) Concentration of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] in the serum of Lewis rats collected various times following a subcutaneous injection of 1 mg/kg PEG-HsTX1[R14A] in the scruff of the neck, as quantified by an anti-PEG ELISA. (B) The circulating half-life of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] was determined by fitting the data in (A) to a single exponential decay (N = 3–8 rats per time point).

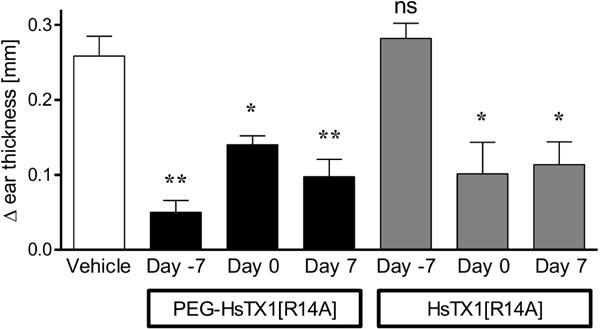

3.6 PEG-HsTX1[R14A] and HsTX1[R14A] reduce a TEM cell-mediated DTH reaction

Kv1.3 blockers reduce inflammation in DTH through inhibiting the activation of TEM cells [25]. ShK-170, an analog of the sea anemone venom peptide ShK, inhibited a DTH reaction when injected at time of challenge, but was ineffective when injected at the time of immunization [2]. To determine if PEG-HsTX1[R14A] and HsTX1[R14A] were effective at reducing inflammation during a DTH reaction, we induced an active DTH reaction against ovalbumin. PEG-HsTX1[R14A] and HsTX1[R14A] were tested when administered subcutaneously a week before immunization, at time of immunization, or at time of challenge. HsTX1[R14A] was administered at 0.1 mg/kg, as the 0.01 – 0.1 mg/kg dose range was effective in preventing a DTH reaction with other Kv1.3 blocking peptides with the same low-picomolar IC50 range as HsTX1[R14A] on Kv1.3 channels by whole-cell patch-clamp [16; 26; 59; 61]. Although PEG-HsTX1[R14A] exhibited a 1,300-fold loss of activity on Kv1.3 by patch-clamp, we chose to test it at 1 mg/kg in the DTH model, a dose only 10-fold higher than that of HsTX1[R14A], to determine whether its long circulating half-life could compensate for the loss of affinity for the target. Both blockers significantly reduced inflammation compared to vehicle-treated rats when administered at time of immunization or at time of challenge. In addition, concurrent with the observation that it is present in the circulation at detectable levels for two weeks, PEG-HsTX1[R14A] displayed efficacy even when given a week before immunization, whereas HsTX1[R14A] did not induce a significant reduction in inflammation when injected at that time (Fig. 6). These data show that PEGylation of HsTX1[R14A] did not compromise its in vivo efficacy, but rather increased the duration of that efficacy.

Fig. 6.

PEG-HsTX1[R14A] and HsTX1[R14A] reduce inflammation in a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction.

Differences in ear thickness of Lewis rats immunized against ovalbumin and then challenged against ovalbumin in one ear and vehicle in the other. Rats were treated with 1 mg/kg PEG-HsTX1[R14A] (black) or with 0.1 mg/kg HsTX1[R14A] (grey) either 7 days prior to immunization, on the day of immunization, or on the day of challenge. Ear thickness was measured 24 h after challenge. Data are normalized to the ear thickness of the vehicle-challenged ear of each rat (N = 4–8 rats per group; mean ± SEM; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, by one-way ANOVA.

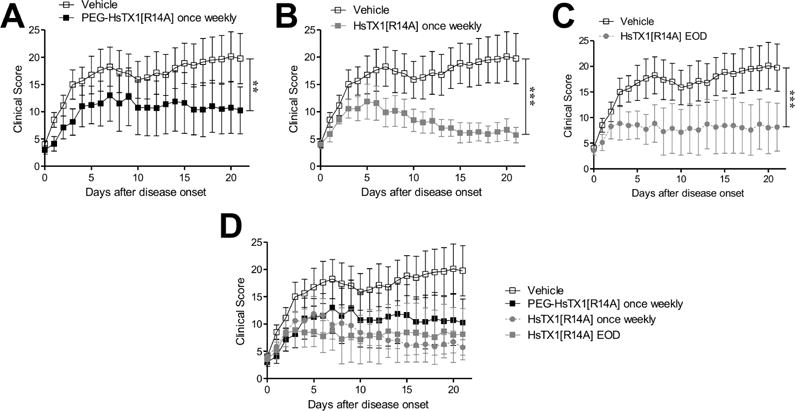

3.7 Both HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] reduce signs of disease in the PIA model of RA

RA and the PIA rat model RA are mediated by TEM cells and disease severity in PIA can be reduced by Kv1.3 blocker treatment given every other day, starting at disease onset [2; 26]. We therefore compared the ability of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] and HsTX1[R14A] to reduce disease severity in PIA. PIA was induced in DA rats and upon disease onset rats were placed randomly in four groups receiving vehicle, PEG-HsTX1[R14A] once weekly, HsTX1[R14A] once weekly, or HsTX1[R14A] every other day. We used the same dosage of the blockers as in the DTH assays. Vehicle-treated rats developed clinical scores of approximately 15–20, indicative of a moderate inflammatory arthritis. Those treated with either PEG-HsTX1[R14A] or HsTX1[R14A] exhibited significantly reduced clinical scores compared to vehicle-treated animals, with an average clinical score of approximately 5–10 (Fig. 7A–D). Interestingly, 0.1 mg/kg HsTX1[R14A] given either every other day or once weekly had similar efficacy at reducing signs of inflammation. The reduction in clinical signs from 1 mg/kg PEG-HsTX1[R14A] once weekly was comparable to that with 0.1 mg/kg of the non-PEGylated HsTX1[R14A] (Fig. 7D). These data indicate that both HsTX1 analogs significantly reduce signs of paw inflammation in this model of RA.

Fig. 7.

PEG-HsTX1[R14A] and HsTX1[R14A] reduce disease severity in PIA.

(A–D) Paw inflammation scores of DA rats with PIA treated with either vehicle (open symbols) or subcutaneous injections of (A) 1 mg/kg PEG-HsTX1[R14A] (black) once weekly, (B) 0.1 mg/kg HsTX1[R14A] (grey) once weekly, or (C) 0.1 mg/kg HsTX1[R14A] (grey) every other day. (D) Data from A–C combined on a single plot for comparison of treatment groups. Treatment began for each rat as it developed signs of disease, as defined by at least one swollen or red joint. N = 7–8 rats per group; mean ± SEM; **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, by Friedman test.

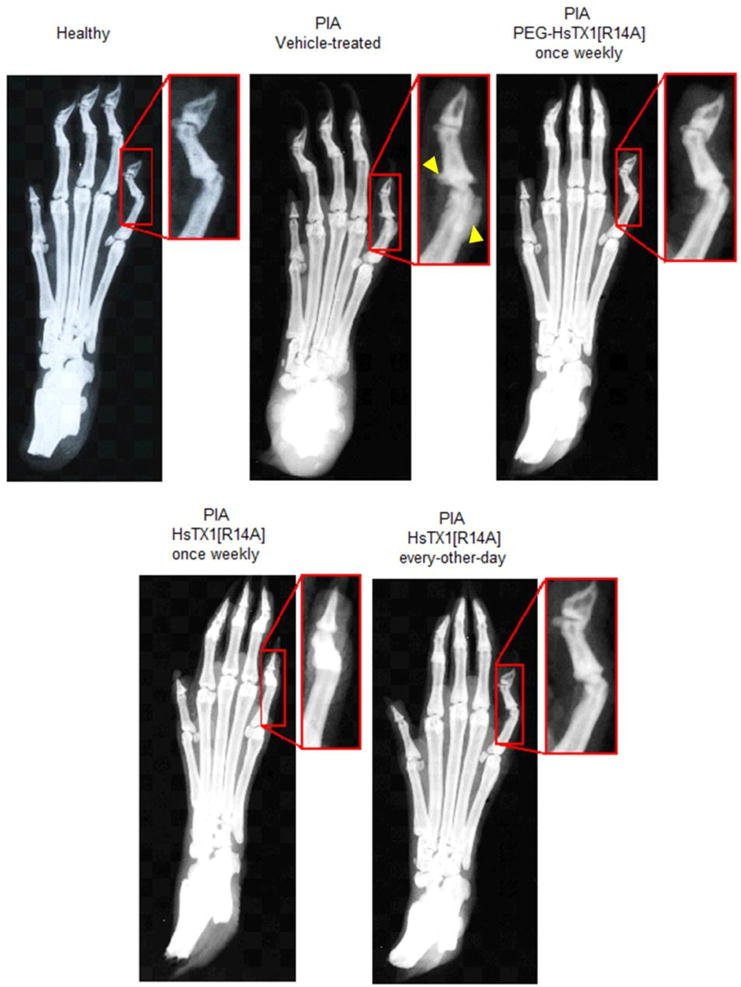

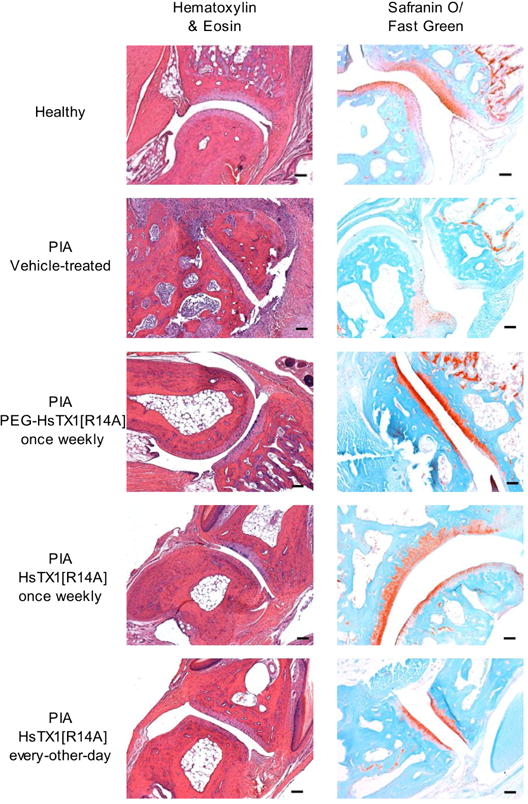

To further examine the effects of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] and HsTX1[R14A] in reducing the severity of PIA, at the end of each in vivo trial, paws from rats of each treatment group were subjected to X-ray and histological analyses in order to determine differences in bone and tissue damage. X-rays of paws from each group indicate that both HsTX1 analogs reduce bone damage in PIA (Fig. 8). Hematoxylin & eosin staining of joint sections show high levels of infiltration of immune cells in the synovium of vehicle-treated PIA animals. Both HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] reduced immune cell infiltration (Fig. 9). Sections stained with Safranin O/Fast Green show a dramatic reduction in cartilage in the vehicle-treated PIA animals. This damage was less pronounced in animals treated with HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

PEG-HsTX1[R14A] and HsTX1[R14A] reduce paw bone damage in PIA.

Representative X-rays of paws from healthy rats (top, left) and rats with PIA treated with either vehicle (top, center), PEG-HsTX1[R14A] once weekly (top, right), HsTX1[R14A] once weekly (bottom, left), or HsTX1[R14A] every other day (bottom, right). Yellow arrows point to damage.

Fig. 9.

PEG-HsTX1[R14A] and HsTX1[R14A] reduce paw tissue damage in PIA.

Hematoxylin & eosin (left) and safranin O/fast green (right) staining of joints from paws from healthy rats and from rats with PIA treated with vehicle, PEG-HsTX1[R14A] once weekly, HsTX1[R14A] once weekly, or HsTX1[R14A] every other day (original magnification 10×, scale bars = 100 μm).

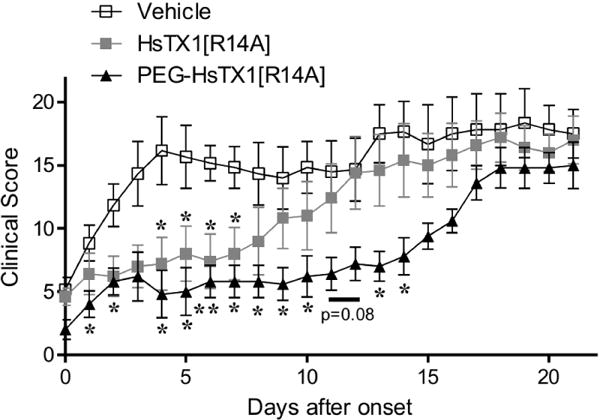

3.8 A single dose of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] is more efficacious than a single dose of HsTX1[R14A] in PIA

Since both HsTX analogs given once weekly reduced disease severity in PIA by similar magnitudes, we sought to determine if a single dose of either PEG-HsTX1[R14A] or HsTX1[R14A] given at the time of disease onset would show different efficacies in reducing signs of disease in PIA. Upon disease onset, rats with PIA were treated with a single subcutaneous dose of either vehicle, 0.1 mg/kg HsTX1[R14A] or 15 mg/kg PEG-HsTX1[R14A] in the scruff of the neck. The dosage of HsTX1[R14A] remained the same as in the prior DTH and PIA assays because 0.1 mg/kg is at the high-end of the range of efficacy for Kv1.3 blockers with low picomolar affinity for the channel; higher dosing does not improve efficacy [26]. To compensate for the 1,300-fold loss in affinity of the PEGylated peptide for Kv1.3, we would have to administer 130 mg/kg to the rats. A weekly dose of 1 mg/kg was effective in the prior PIA assays. We did, however, increase the dosage for PEG-HsTX1[R14A] to 15 mg/kg because in the prior PIA trials the response of rats to the 1 mg/kg PEG-HsTX1[R14A] was highly variable, suggesting that we were close to the low-end of its efficacy range. In addition, these trials were planned for summer when susceptibility to autoimmune diseases and their severity is higher [62], whereas the prior PIA trials were conducted in winter.

Clinical scores quantifying paw inflammation indicate that a single treatment of HsTX1[R14A] induced a significant reduction in clinical signs for up to seven days post-treatment, at which time paw inflammation became comparable to that of vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 10). Animals treated with a single dose of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] had significantly reduced signs of disease for up to fourteen days after treatment (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

A single treatment of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] is more effective than a single treatment of HsTX1[R14A] in PIA.

Paw inflammation scores from DA rats with PIA treated with either vehicle (open symbols), or subcutaneous treatments of a single treatment of 0.1 mg/kg HsTX1[R14A] (closed grey squares) at time of onset, or a single treatment of 15 mg/kg PEG-HsTX1[R14A] (closed black triangles) at time of onset. Treatments were given once a rat exhibited at least one swollen or red joint. N = 5 – 6 rats per group; mean ± SEM; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, by Mann-Whitney U-tests.

3.9. HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] do not induce changes in blood chemistries during PIA trials

None of the rats treated with either peptide showed overt signs of toxicity, such as weight loss, reduced grooming or social interactions, aggression, huddled posturing, or porphyrins during the 21-day long PIA studies. Blood collected at the end of these studies was used to assess blood chemistry. Rats with PIA that were treated with vehicle had variable levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Some had high levels of this marker of acute or chronic tissue damage (Table 2). LDH levels were normalized by the administration of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] or HsTX1[R14A] to PIA rats. None of the other measured parameters was altered significantly.

Table 2.

Chemistry analysis of serum from healthy rats and from rats with PIA treated with vehicle, PEG-HsTX1[R14A] once weekly, HsTX1[R14A] once weekly, HsTX1[R14A] every other day PEG-HsTX1[R14A] once at time of onset, HsTX1[R14A] or once at time of onset. Data are shown as mean (standard deviation) of N = 5 rats per group.

| Healthy | PIA, Vehicle | PIA, PEG-HsTX[R14A] weekly | PIA, HsTX[R14A] weekly | PIA, HsTX[R14A] EOD | PIA, PEG-HsTX[R14A] once | PIA, HsTX[R14A] once | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 143.8 (16.7) |

141 (4.6) |

149.2 (8.4) |

143.8 (3.8) |

130 (1.0) |

130.8 (1.3) |

131.2 (2.3) |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.8 (0.04) |

5.44 (1.12) |

4.76 (0.26) |

4.56 (0.19) |

4.68 (0.51) |

4.86 (0.45) |

4.76 (0.86) |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 109.2 (10.2) |

107.6 (3.0) |

114.4 (7.2) |

108.8 (2.8) |

99.4 (1.1) |

98.6 (1.5) |

98.6 (0.5) |

| CO2 (mmol/L) | 22.2 (2.86) |

19.2 (2.59) |

22 (1.58) |

21 (1.87) |

19.8 (2.39) |

18.6 (2.61) |

19 (1.41) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.66 (1.14) |

3.26 (0.51) |

3.48 (0.44) |

3.62 (0.31) |

3.04 (0.32) |

3.64 (0.25) |

3.76 (0.48) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.2 (0) |

0.14 (0.05) |

0.2 (0) |

0.2 (0) |

0.16 (0.05) |

0.16 (0.05) |

0.2 (0) |

| Total Proteins (g/dL) | 6.7 (1.7) |

4.7 (0.23) |

4.72 (0.19) |

4.76 (0.34) |

4.34 (0.21) |

4.74 (0.17) |

4.92 (0.56) |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 1.875 (0.544) |

1.46 (0.313) |

1.22 (0.27) |

1.16 (0.15) |

1.28 (0.48) |

1.12 (0.13) |

1.18 (0.16) |

| Albumin/globulin ratio | 2.33 (0.29) |

2.36 (0.70) |

3.02 (0.91) |

3.24 (0.53) |

2.74 (1.14) |

3.28 (0.52) |

3.14 (0.42) |

| Alanine aminotransferase [ALT] (U/L) | 81 (19.9) |

54.4 (8.26) |

56.2 (4.65) |

59.6 (6.19) |

51.4 (3.05) |

43.8 (179) |

52.2 (5.22) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase [AST] (U/L) | 123.6 (23.6) |

99.8 (23.4) |

97.4 (32.5) |

86.4 (31.6) |

111.8 (43.6) |

90.2 (18.0) |

116.4 (47.8) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 61 (18.3) |

46.8 (17.0) |

55.6 (12.7) |

54.8 (8.6) |

57 (15.4) |

46.2 (2.6) |

52 (15.0) |

| Creatine kinase (U/L) | 383.6 (134.3) |

404.2 (156.3) |

386 (228.3) |

314.2 (245.2) |

417.8 (237.9) |

335.2 (159.6) |

443.4 (317.7) |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase (U/L) | 0.75 (.5) |

2.75 (2.06) |

0 (0) |

0.2 (0.4) |

1.5 (0.7) |

2.5 (0.7) |

1.2 (2.7) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase [LDH] (U/L) | 692 (119.3) |

1128.6 (779.3) |

510.8 (196.9) |

479.6 (172.3) |

639.6 (425.8) |

657 (388.1) |

581.6 (495.9) |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 12.96 (1.63) |

12.38 (0.85) |

12.72 (1.18) |

13.62 (0.88) |

11.38 (1.39) |

10.78 (1.36) |

11.14 (2.26) |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 140.2 (17.5) |

132.8 (24.5) |

133.2 (22.5) |

121.2 (11.4) |

104.6 (21.2) |

117.6 (19.1) |

123.8 (21.9) |

| Osmolality (mOsm) | 288.88 (32.29) |

282.94 (9.17) |

298.24 (16.36) |

288.04 (6.93) |

261.26 (2.20) |

262.68 (3.09) |

263.92 (4.71) |

| Bilirubin direct (mg/dL) | 0 (0) |

0.002 (0.004) |

0.007 (0.006) |

0.007 (0.006) |

0.002 (0.004) |

0 (0) |

0.002 (0.004) |

| Indirect Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.02 (0.04) |

0.02 (0.04) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.02 (0.04) |

0.04 (0.05) |

0.02 (0.04) |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 103.4 (25.7) |

71.8 (3.6) |

73.6 (8.5) |

76 (11.3) |

66.8 (2.2) |

80.8 (7.2) |

79.4 (11.2) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 75.4 (26.3) |

43.4 (8.9) |

34.8 (14.4) |

54.2 (42.8) |

45.2 (14.9) |

70.2 (36.3) |

66 (15.3) |

| Very low density lipoprotein [VLDL] (mg/dL) | 15.1 (5.26) |

8.66 (1.82) |

6.94 (2.9) |

10.8 (8.52) |

9 (2.99) |

14 (7.26) |

13.2 (3.09) |

| Magnesium (mg/dL) | 2.22 (0.36) |

2.04 (0.11) |

2.1 (0.1) |

2.06 (0.13) |

1.94 (0.13) |

1.96 (0.11) |

2.04 (0.18) |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 5.52 (0.80) |

4.1 (0.76) |

4.06 (0.15) |

3.98 (0.44) |

5.3 (0.91) |

6.18 (0.74) |

5.12 (0.44) |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 11.28 (2.28) |

6.852 (0.329) |

7.364 (0.349) |

7.036 (0.315) |

8.96 (0.246) |

9.472 (0.671) |

9.36 (0.781) |

4. Discussion

Kv1.3 channels play a key role in regulating the pro-inflammatory phenotype of CCR7− TEM lymphocytes, which are major drivers of autoimmune inflammation [13]. In this study we demonstrated the effectiveness of two analogs of the HsTX1 scorpion venom toxin, HsTX1[R14A] and its PEGylated analog, as potent and selective blockers of the Kv1.3 potassium channel. We characterized their efficacy in reducing the proliferation of rat and human TEM lymphocytes and their ability to limit inflammation in an animal model of autoimmunity. We found that HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] were selective for the Kv1.3 channel over other Kv1 channels and preferentially inhibited TEM cell proliferation. The PEGylated analog also exhibited reduced adsorption to polystyrene surfaces and a prolonged circulating half-life. While both analogs displayed efficacy in stopping the progression of disease in PIA, a single dose of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] reduced inflammation in the PIA model of RA for double the duration of HsTX1[R14A].

Our data showing a low picomolar affinity of HsTX1[R14A] are in agreement with the previous publication describing the generation of this peptide [33]. Its PEGylation with a 30 kDa PEG moiety resulted in a 1,300-fold reduction in affinity for Kv1.3. Such a change in affinity was expected as attaching large moieties to ion channel modulating peptides is known to significantly reduce or even eliminate their affinity for their target. For example, fusing OsK1, OdK2, or ShK with Fc fragments of immunoglobulins, with PEG moieties, or with albumin reduced their affinity for Kv1.3 channels to varying degrees [40; 63]. A thioredoxin fusion of ShK or a biotin-tagged ShK bound to streptavidin had no effect on Kv1.3 currents at 100 nM, whereas ShK itself blocks the channel with low picomolar affinity [44; 64].

Importantly, the PEGylation of HsTX1[R14A] retained a 250-fold or higher selectivity for Kv1.3 over closely-related Kv1.1, Kv1.2, Kv1.4, and Kv1.5 channels. Such selectivity is crucial for the development of potential therapeutics to avoid any detrimental off-target effects. Indeed, loss of Kv1.1 or of Kv1.2 expression or function is associated with epilepsy and ataxia [65]. In addition, loss of Kv1.1 has been linked to sudden death in epilepsy [66]. Mutations in KCNA5, the gene encoding for Kv1.5, were identified in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension [67] and with atrial fibrillation [68; 69]. In comparison, ShK-186, currently in clinical trials[31], displays “only” a 100-fold selectivity for Kv1.3 over Kv1.1 and is well tolerated in rats, nonhuman primates and humans[13; 15].

PEGylation of HsTX1[R14A] induced a 1,300-fold reduction in affinity for Kv1.3 when compared to HsTX1[R14A]. However, both compounds inhibited the proliferation of human and rat TEM lymphocytes at similar concentrations, in the mid-to-low nanomolar range. During patch-clamp testing of blockers, the compounds are diluted in the external solution immediately before application to the cells and the readout occurs within minutes. In contrast, proliferation assays require multiple days of incubation in microplates. Peptides such as HsTX1 and its analogs are known to adsorb onto surfaces, such as the polystyrene in the microplates used in proliferation assays. PEGylation has been proposed as a means for reducing peptide and protein adsorption onto surfaces [55; 56; 57; 58]. We therefore assayed the recovery of HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] after a 24 h incubation in the microplates used for our proliferation assays and, indeed, we observed a much lower recovery of HsTX1[R14A] than of its PEGylated analog. This suggests a loss of peptide during the multi-day proliferation assays and thus an apparent loss in inhibitory efficacy in TEM cell proliferation assays.

The proliferation assays with human CCR7− TEM cells and CCR7+ naïve/TCM cells showed that both HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] inhibited the former but not the latter. Previous work with human T lymphocytes showed that, while Kv1.3 channel blockers preferentially inhibit CCR7− TEM cells, they also affect the proliferation of CCR7+ naïve/TCM cells to some degree [2; 3; 7; 16]. This apparent discrepancy in results is likely due to the difference in incubation times. Previous assays used proliferation assays over a 72-hr period whereas the use of CellTrace Violet to measure proliferation required a 7-day incubation period. Following activation, CCR7+ naïve/TCM lymphocytes up-regulate the KCa3.1 channel and become completely resistant to Kv1.3 channel block [7; 16]. This up-regulation takes approximately 24 h, during which the cells are not dividing due to presence of the Kv1.3 channel blocker [7; 16; 70]. This delay in proliferation is presumably masked during a 7-day proliferation assay but still detectable during a shorter 3-day assay.

We used [3H] thymidine incorporation to measure proliferation of rat T cells and CellTrace Violet dye dilution to measure human T cell proliferation. The CellTrace Violet-based assay was beneficial in that it allowed for the simultaneous analysis of CCR7+ and CCR7− T cells, along with distinguishing T lymphocytes from other cells in the peripheral blood without having to sort the cells before the assay. This reduced the risk of bias induced by antibody binding to the cells for sorting prior to activation. However, we found that CellTrace Violet, used at the manufacturer-recommended concentration, was toxic to rat T cells, but not to human T cells (data not shown). For this reason, [3H] thymidine incorporation-based analysis of proliferation was used for the study of rat T cell proliferation.

Our studies utilized two rat models of inflammation, as well as rat T cells ex vivo, to examine the effects of PEG-HsTX1[R14A] and HsTX1[R14A] in reducing TEM lymphocyte-mediated inflammation. Rats were chosen for these studies as mouse T lymphocytes exhibit significant differences in their potassium channel phenotype when compared to human T cells and thus are not useful models for studying Kv1.3 channel blockers [17]. In contrast, the activation of both human and rat TEM cells is regulated by Kv1.3 and block of this channel is known to inhibit TEM cells [2; 18], making rat models of autoimmunity more suitable than mouse models for the evaluation of Kv1.3 blockers in reducing a TEM cell-mediated inflammation.

Whereas peptide Kv1.3 blockers have a short circulating half-life, of less than an hour, PEG-HsTX1[R14A] was detectable in rat serum 14 days after a single subcutaneous injection. These results demonstrate that attaching a large PEG moiety to a peptide Kv1.3 blocker can dramatically extend its retention in the circulation. Our findings are in agreement with previous work showing extended circulating half-lives for peptides fused with Fc fragments of immunoglobulins or albumin [63]. In contrast to the previously described albumin-fusion peptide [63], PEG-HsTX1[R14A] was effective in reducing inflammation in an active DTH model. Since ShK-186 was effective in reducing an active DTH reaction when injected at time of challenge, but not when injected at time of immunization [2], we expected that HsTX1[R14A] would display a similar pattern. Surprisingly, HsTX1[R14A] was efficacious whether it was administered at time of immunization or challenge. Similarly, whereas ShK-186 showed efficacy when injected daily, every other day, or every 3 days in a chronic model of autoimmunity mediated by TEM cells in rats [26], HsTX1[R14A] displayed efficacy when given every other day or once weekly. These results suggest that HsTX1[R14A] has a longer window of efficacy than ShK-186 or that efficacy was disease-dependent, as ShK-186 was tested in a model of multiple sclerosis whereas HsTX1[R14A] was tested in the PIA model. We therefore tested the benefits of a single administration of HsTX1[R14A] in the PIA model of RA. As found with ShK-186 in the model of multiple sclerosis [26], administration of a single dose of HsTX1[R14A] was efficacious for one week. PEG-HsTX1[R14A] displayed efficacy when administered weekly in the PIA model. Importantly, a single dose of this analog was efficacious in reducing the severity of clinical scores of PIA for 2 weeks.

In the PIA data shown in Fig. 7, the vehicle-treated animals have a much wider range of disease severity than the vehicle-treated animals in the PIA data shown in Fig. 10. This range in responses can be the result of multiple variables. The data in Fig. 7 were acquired in February while the data in Fig. 10 were acquired in August. Seasonality is a factor in autoimmune disease onset and severity in humans but also in animals, even those maintained in climate- and light-controlled environments[62; 71]. In addition, the localization of the injection of pristane for PIA induction needs to be very precise and any variability may affect disease incidence and severity. Since an early onset of clinical signs often correlates with a higher disease severity, to avoid any bias due to this factor, animals were assigned to the different groups at onset of clinical signs as described in the methods section.

Although both HsTX1 analogs significantly prevented disease progression in PIA, neither caused a reduction in disease severity. These findings are in agreement with previous findings regarding the efficacy of Kv1.3 blockers in treating PIA [2; 26]. This may be due to other cell-types involved with inflammatory arthritis pathophysiology that are not regulated by Kv1.3 channels, such as fibroblast-like synoviocytes, chondrocytes, or osteoclasts [54; 72; 73; 74; 75; 76]. It may be necessary to target these cell-types, along with TEM cells, to fully eliminate the inflammation and joint damage associated with RA and PIA.

Our data show that PEGylation of HsTX1[R14A] reduced its affinity for Kv1.3 channels without affecting its selectivity. This reduction in affinity was countered by the reduction in loss of peptide to adsorption to polystyrene surfaces, making HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] similar in efficacy for the inhibition of the proliferation of human and rat TEM cells ex vivo. PEG-HsTX1[R14A] not only retained the efficacy of HsTX1[R14A] in reducing inflammation in active DTH and in the PIA model of RA, but also enhanced the circulating half-life of the Kv1.3 blocker and extended the efficacy window from 1 to 2 weeks following a single subcutaneous injection. These properties make PEG-HsTX1[R14A] an attractive potential therapeutic for the treatment of RA and other TEM cell-mediated inflammatory diseases.

Highlights.

PEGylation of HsTX1[R14A] does not reduce its selectivity for Kv1.3 channels.

PEG-HsTX1[R14A] retains preferential inhibition of CCR7− over CCR7+ T lymphocytes.

PEG-HsTX1[R14A] has a longer circulating half-life and lower non-specific adsorption.

HsTX1[R14A] and PEG-HsTX1[R14A] reduce inflammation in delayed type hypersensitivity.

Both HsTX1 analogs attenuate disease severity in a model of rheumatoid arthritis.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Baylor College of Medicine and National Institutes of Health awards NS073712 (to C.B., M.W.P. and R.S.N.) and AI084981 (to C.B.). M.R.T. was supported by T32 awards GM088129 and AI053831 and by F31 award AR069960 from the National Institutes of Health. R.H. was supported by T32 award HL007676 from the National Institutes of Health. E.J.G. was supported by the Robert W. Beart Endowment in Chemistry to Augustana College (Rock Island, IL). K.E.R. was supported by National Institutes of Health awards GM118969, GM118971, and GM118970. R.S.N. acknowledges fellowship support from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. The Cytometry & Cell Sorting, Mouse Phenotyping, and Pathology & Histology cores at Baylor College of Medicine are supported in part by funding from the National Institutes of Health (HG006348, RR024574, and CA125123) and the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine.

Abbreviations

- DTH

delayed-type hypersensitivity

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PIA

pristane-induced arthritis

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- TCM cell

central memory T cell

- TEM cell

effector memory T cell

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions

MRT, RSN, MWP, and CB designed the study, MWP designed and synthesized HsTX1[R14A] and its PEGylated analog, RBT and CB performed the electrophysiology, RH and KR performed the proliferation assays, MRT and RH performed the pharmacokinetic studies, MRT and CB performed the DTH assays, MRT and EG performed the PIA assays, MRT performed the X-rays, the histology, and the blood chemistry, MRT and CB wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

References

- 1.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Förster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401:708–712. doi: 10.1038/44385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beeton C, Wulff H, Standifer N, Azam P, Mullen K, Pennington M, Kolski-Andreaco A, Wei E, Grino A, Counts D, Wang P, LeeHealey C, Andrews BS, Sankaranarayanan A, Homerick D, Roeck W, Tehranzadeh J, Stanhope K, Zimin P, Havel P, Griffey S, Knaus H, Nepom G, Gutman G, Calabresi P, Chandy K. Kv1.3 channels are a therapeutic target for T cell-mediated autoimmune diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(46):17414–17419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605136103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koshy S, Huq R, Tanner M, Atik M, Porter P, Khan F, Pennington M, Hanania N, Corry D, Beeton C. Blocking KV1.3 channels inhibits Th2 lymphocyte function and treats a rat model of asthma. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(18):12623–12632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.517037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis C, Krueger G. Treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis by selective targeting of memory effector T lymphocytes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:248–255. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107263450403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markovic-Plese S, Cortese I, Wandinger K, McFarland H, Martin R. CD4+CD28− costimulation-independent T cells in multiple sclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1185–1194. doi: 10.1172/JCI12516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viglietta V, Kent S, Orban T, Hafler D. GAD65-reactive T cells are activated in patients with autoimmune type 1a diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:895–903. doi: 10.1172/JCI14114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wulff H, Calabresi P, Allie R, Yun S, Pennington M, Beeton C, Chandy K. The voltage-gated Kv1.3 K(+) channel in effector memory T cells as new target for MS. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1703–1713. doi: 10.1172/JCI16921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rus H, Pardo C, Hu L, Darrah E, Cudrici C, Niculescu T, Niculescu F, Mullen K, Allie R, Guo L, Wulff H, Beeton C, Judge S, Kerr D, Knaus H, Chandy K, Calabresi P. The voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3 is highly expressed on inflammatory infiltrates in multiple sclerosis brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;201:11094–11099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501770102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinkse G, Tysma O, Bergen C, Kester M, Ossendorp F, Van Veelen P, Keymeulen B, Pipeleers D, Drijfhout J, Roep B. Autoreactive CD8 T cells associated with beta cell destruction in type 1 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18425–18430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508621102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rinaldi L, Gallo P, Calabrese M, Ranzato F, Luise D, Colavito D, Motta M, Guglielmo A, Giudice E Del, Romualdi C, Ragazzi E, D’Arrigo A, Carbonare M Dalle, Leontino B, Leon A. Longitudinal analysis of immune cell phenotypes in early stage multiple sclerosis: distinctive patterns characterize MRI-active patients. Brain. 2006;129:1993–2007. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davalos-Misslitz A, Rieckenberg J, Willenzon S, Worbs T, Kremmer E, Bernhardt G, Förster R. Generalized multi-organ autoimmunity in CCR7-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:613–622. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wulff H, Beeton C, Chandy K. Potassium channels as therapeutic targets for autoimmune disorders. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2003;6:640–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chi V, Pennington M, Norton R, Tarcha E, Londono L, Sims-Fahey B, Upadhyay S, Lakey J, Iadonato S, Wulff H, Beeton C, Chandy K. Development of a sea anemone toxin as an immunomodulator for therapy of autoimmune diseases. Toxicon. 2012;59 doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandy K, Wulff H, Beeton C, Pennington M, Gutman G, Cahalan M. K+ channels as targets for specific immunomodulation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:280–289. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beeton C, Pennington M, Norton R. Analogs of the sea anemone potassium channel blocker ShK for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2011;10:313–321. doi: 10.2174/187152811797200641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beeton C, Pennington M, Wulff H, Singh S, Nugent D, Crossley G, Khaytin I, Calabresi P, Chen C, Gutman G, Chandy K. Targeting effector memory T cells with a selective peptide inhibitor of Kv1.3 channels for therapy of autoimmune diseases. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:1369–1381. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.008193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beeton C, Chandy K. Potassium channels, memory T cells and multiple sclerosis. Neuroscientist. 2005;11:550–562. doi: 10.1177/1073858405278016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beeton C, Wulff H, Barbaria J, Clot-Faybesse O, Pennington M, Bernard D, Cahalan M, Chandy K, Beraud E. Selective blockade of T lymphocyte K(+) channels ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a model for multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(24):13942–13947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241497298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilhar A, Keren A, Shemer A, Ullmann Y, Paus R. Blocking potassium channels (Kv1.3): a new treatment option for alopecia areata? J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(8):2088–2091. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koch Hansen L, Sevelsted-Møller L, Rabjerg M, Larsen D, Hansen T, Klinge L, Wulff H, Knudsen T, Kjedlsen J, Köhler R. Expression of T-cell KV1.3 potassium channel correlates with proinflammatory cytokines and disease activity in ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(11):1378–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Upadhyay S, Eckel-Mahan K, Mirbolooki M, Tjong I, Griffey S, Schmunk G, Koehne A, Halbout B, Iadonato S, Pedersen B, Borrelli E, Wang P, Mukherjee J, Sassone-Corsi P, Chandy K. Selective Kv1.3 channel blocker as therapeutic for obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(24):E2239–E2248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221206110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyodo T, Oda T, Kikuchi Y, Higashi K, Kushiyama T, Yamamoto K, Yamada M, Suzuki S, Hokari R, Kinoshita M, Seki S, Fujinaka H, Yamamoto T, Miura S, Kumagai H. Voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3 blocker as a potential treatment for rat anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299(6):F1258–F1269. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00374.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kundu-Raychaudhuri S, Chen Y, Wulff H. Kv1.3 in psoriatic disease: PAP-1, a small molecule inhibitor of Kv1.3 is effective in the SCID mouse psoriasis–xenograft model. J Autoimmun. 2014;55:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Legány N, Toldi G, Orbán C, Megyes N, Bajnok A, Balog A. Calcium influx kinetics, and the features of potassium channels of peripheral lymphocytes in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Immunobiology. 2016;221:1266–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matheu M, Beeton C, Garcia A, Chi V, Rangaraju S, Safrina O, Monaghan K, Uemura M, Li D, Pal S, Maza L de la, Monuki E, Flügel A, Pennington M, Parker I, Chandy K, Cahalan M. Imaging of effector memory T cells during a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction and suppression by Kv1.3 channel block. Immunity. 2008;29:602–614. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarcha E, Chi V, Munoz-Elias E, Bailey D, Londono L, Upadhyay S, Norton K, Banks A, Tjong I, Nguyen H, Hu X, Ruppert G, Boley S, Slauter R, Sams J, Knapp B, Kentala D, Hansen Z, Pennington M, Beeton C, Chandy K, Iadonato S. Durable Pharmacological Responses from the Peptide ShK-186, a Specific Kv1.3 Channel Inhibitor That Suppresses T Cell Mediators of Autoimmune Disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;342:642–653. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.191890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beeton C, Barbaria J, Giraud P, Devaux J, Benoliel A, Gola M, Sabatier J, Bernard D, Crest M, Béraud E. Selective blocking of voltage-gated K+ channels improves experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and inhibits T cell activation. J Immunol. 2001;166:936–944. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valverde P, Kawai T, Taubman M. Selective blockade of voltage-gated potassium channels reduces inflammatory bone resorption in experimental periodontal disease. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:155–164. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chhabra S, Chang S, Nguyen H, Huq R, Tanner M, Londono L, Estrada R, Dhawan V, Chauhan S, Upadhyay S, Gindin M, Hotez P, Valenzuela J, Mohanty B, Swarbrick J, Wulff H, Iadonato S, Gutman G, Beeton C, Pennington M, Norton R, Chandy K. Kv1.3 channel-blocking immunomodulatory peptides from parasitic worms: implications for autoimmune diseases. FASEB J. 2014;28:3952–3964. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-251967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chandy K, Beeton C, Pennington M. Patent WO/2006/042151 Analogs of ShK toxin and their uses in selective inhibition of Kv1.3 potassium channels. 2006

- 31.Munoz-Elias E, Peckham D, Norton K, Duculan J, Cueto I, Li X, Qin J, Lustig K, Tarcha E, Odegard J, Krueger J, Iadonato S. Dalazatide (ShK-186), a first-in-class blocker of Kv1.3 potassium channel on effector memory T cells: safety, tolerability and proof of concept of immunomodulation in patients with active plaque psoriasis [abstract] Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(suppl 10) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lebrun B, Romi-Lebrun R, Martin-Eauclaire M, Yasuda A, Ishiguro M, Oyama Y, Pongs O, Nakajima T. A four-disulphide-bridged toxin, with high affinity towards voltage-gated K+ channels, isolated from Heterometrus spinnifer (Scorpionidae) venom. Biochem J. 1997;328:321–327. doi: 10.1042/bj3280321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rashid M, Huq R, Tanner M, Chhabra S, Khoo K, Estrada R, Dhawan V, Chauhan S, Pennington M, Beeton C, Kuyucak S, Norton R. A potent and Kv1.3-selective analogue of the scorpion toxin HsTX1 as a potential therapeutic for autoimmune diseases. Sci Rep. 2014;4:e4509. doi: 10.1038/srep04509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Regaya I, Beeton C, Ferrat G, Andreotti N, Darbon H, De Waard M, Sabatier J. Evidence for domain-specific recognition of SK and Kv channels by MTX and HsTx1 scorpion toxins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55690–55696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410055200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carrega L, Mosbah A, Ferrat G, Beeton C, Andreotti N, Mansuelle P, Darbon H, De Waard M, Sabatier J. The impact of the fourth disulfide bridge in scorpion toxins of the alpha-KTx6 subfamily. Proteins. 2005;61:1010–1023. doi: 10.1002/prot.20681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jin L, Zhou Q, Chan H, Larson I, Pennington M, Morales R, Boyd B, Norton R, Nicolazzo J. Pulmonary Delivery of the Kv1.3-Blocking Peptide HsTX1[R14A] for the Treatment of Autoimmune Diseases. J Pharm Sci. 2016;105(2):650–656. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin L, Boyd B, Larson I, Pennington M, Norton R, Nicolazzo J. Enabling Noninvasive Systemic Delivery of the Kv1.3-Blocking Peptide HsTX1[R14A] via the Buccal Mucosa. J Pharm Sci. 2016;105(7) doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turecek P, Bossard M, Schoetens F, Ivens I. PEGylation of biopharmaceuticals: a review of chemistry and nonclinical safety information of approved drugs. J Pharm Sci. 2016;105(2):460–475. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harris J, Chess R. Effect of pegylation on pharmaceuticals. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2(3):214–221. doi: 10.1038/nrd1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray J, Qian Y, Liu B, Elliott R, Aral J, Park C, Zhang X, Stenkilsson M, Salyers K, Rose M, Li H, Yu S, Andrews K, Colombero A, Werner J, Gaida K, Sickmier E, Miu P, Itano A, McGivern J, Gegg C, Sullivan J, Miranda L. Pharmaceutical Optimization of Peptide Toxins for Ion Channel Targets: Potent, Selective, and Long-Lived Antagonists of Kv1.3. J Med Chem. 2015;58:6784–6802. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alexander S, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters J, Benson H, Faccenda E, Pawson A, Sharman J, Southan C, Buneman O, Catterall W, Cidlowski J, Davenport A, Fabbro D, Fan G, McGrath J, Spedding M, Davies J. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Overview. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:5729–5743. doi: 10.1111/bph.13355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grissmer S, Nguyen A, Aiyar J, Hanson D, Mather R, Gutman G, Karmilowicz M, Auperin D, Chandy K. Pharmacological characterization of five cloned voltage-gated K+ channels, types Kv1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, and 3.1, stably expressed in mammalian cell lines. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:1227–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Felipe A, Snyders D, Deal K, Tamkun M. Influence of cloned voltage-gated K+ channel expression on alanine transport, Rb+ uptake, and cell volume. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:1230–1238. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.5.C1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beeton C, Wulff H, Singh S, Botsko S, Crossley G, Gutman G, Cahalan M, Pennington M, Chandy K. A novel fluorescent toxin to detect and investigate Kv1.3 channel up-regulation in chronically activated T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9928–9937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212868200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pennington M, Rashid M Harunur, Tajhya R, Beeton C, Kuyucak S, Norton R. A C-terminally amidated analogue of ShK is a potent and selective blocker of the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:3996–4001. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rashid M, Heinzelmann G, Huq R, Tajhya R, Chang S, Chhabra S, Pennington M, Beeton C, Norton R, Kuyucak S. A potent and selective peptide blocker of the Kv1.3 channel: prediction from free-energy simulations and experimental confirmation. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pennington M, Chang S, Chauhan S, Huq R, Tajhya R, Chhabra S, Norton R, Beeton C. Development of highly selective Kv1.3-blocking peptides based on the sea anemone peptide ShK. Mar Drugs. 2015;13:529–542. doi: 10.3390/md13010529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flügel A, Willem M, Berkowicz T, Wekerle H. Gene transfer into CD4+ T lymphocytes: green fluorescent protein-engineered, encephalitogenic T cells illuminate brain autoimmune responses. Nat Med. 1999;5:843–847. doi: 10.1038/10567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beeton C, Chandy K. Preparing T cell growth factor from rat splenocytes. J Vis Exp. 2007;10:402. doi: 10.3791/402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huq R, Samuel E, Sikkema W, Nilewski L, Lee T, Tanner M, Khan F, Porter P, Tajhya R, Patel R, Inoue T, Pautler R, Corry D, Tour J, Beeton C. Preferential uptake of antioxidant carbon nanoparticles by T lymphocytes for immunomodulation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33808. doi: 10.1038/srep33808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beeton C, Garcia A, Chandy K. Drawing Blood from Rats through the Saphenous Vein and by Cardiac Puncture. J Vis Exp. 2007;7:266. doi: 10.3791/266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beeton C, Chandy K. Induction and Monitoring of Active Delayed Type Hypersensitivity (DTH) in Rats. J Vis Exp. 2007;6:e237. doi: 10.3791/237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beeton C, Chandy K. Induction and Monitoring of Adoptive Delayed-Type Hypersensitivity in Rats. J Vis Exp. 2007;8:325. doi: 10.3791/325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanner M, Hu X, Huq R, Tajhya R, Sun L, Khan F, Laragione T, Horrigan F, Gulko P, Beeton C. KCa1.1 inhibition attenuates fibroblast-like synoviocyte invasiveness and ameliorates disease in rat models of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(1):96–106. doi: 10.1002/art.38883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pochechueva T, Chinarev A, Bovin N, Fedier A, Jacob F, Heinzelmann-Schwarz V. PEGylation of microbead surfaces reduces unspecific antibody binding in glycan-based suspension array. J Immunol Methods. 2014;412:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2014.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goebel-Stengel M, Stengel A, Taché Y, Reeve J. The importance of using the optimal plasticware and glassware in studies involving peptides. Anal Biochem. 2011;414:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kristensen K, Henriksen J, Andresen T. Adsorption of cationic peptides to solid surfaces of glass and plastic. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Charles P, Stubbs V, Soto C, Martin B, White B, Taitt C. Reduction of Non-Specific Protein Adsorption Using Poly(ethylene) Glycol (PEG) Modified Polyacrylate Hydrogels In Immunoassays for Staphylococcal Enterotoxin B Detection Sensors (Basel) 2009;9:645–655. doi: 10.3390/s90100645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pennington M, Beeton C, Galea C, Smith B, Chi V, Monaghan K, Garcia A, Rangaraju S, Giuffrida A, Plank D, Crossley G, Nugent D, Khaytin I, Lefievre Y, Peshenko I, Dixon C, Chauhan S, Orzel A, Inoue T, Hu X, Moore R, Norton R, Chandy K. Engineering a stable and selective peptide blocker of the Kv1.3 channel in T lymphocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:762–773. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.052704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beeton C, Smith B, Sabo J, Crossley G, Nugent D, Khaytin I, Chi V, Chandy K, Pennington M, Norton R. The D-diastereomer of ShK toxin selectively blocks voltage-gated K+ channels and inhibits T lymphocyte proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:988–997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Varga Z, Gurrola-Briones G, Papp F, Rodriguez de la Vega RC, Pedraza-Alva G, Tajhya RB, Gaspar R, Cardenas L, Rosenstein Y, Beeton C, Possani LD, Panyi G. Vm24, a natural immunosuppressant peptide potently and selectively blocks Kv1.3 potassium channels of human T cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;82:372–382. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.078006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Teuscher C, Bunn J, Fillmore P, Butterfield R, Zachary J, Blankenhorn E. Gender, age, and season at immunization uniquely influence the genetic control of susceptibility to histopathological lesions and clinical signs of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis: implications for the genetics of multiple sclerosis. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1593–1602. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63416-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Edwards W, Fung-Leung W, Huang C, Chi E, Wu N, Liu Y, Maher M, Bonesteel R, Connor J, Fellows R, Garcia E, Lee J, Lu L, Ngo K, Scott B, Zhou H, Swanson R, Wickenden A. Targeting the ion channel Kv1.3 with scorpion venom peptides engineered for potency, selectivity, and half-life. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:22704–22714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.568642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chang S, Galea C, Leung E, Tajhya R, Beeton C, Pennington M, Norton R. Expression and isotopic labelling of the potassium channel blocker ShK toxin as a thioredoxin fusion protein in bacteria. Toxicon. 2012;60:840–850. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robins C, Tempel B. Kv1.1 and Kv1.2: similar channels, different seizure models. Epilepsia. 2012;53:134–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Glasscock E, Yoo J, Chen T, Klassen T, Noebels J. Kv1.1 potassium channel deficiency reveals brain-driven cardiac dysfunction as a candidate mechanism for sudden unexplained death in epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5167–5175. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5591-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Remillard C, Tigno D, Platoshyn O, Burg E, Brevnova E, Conger D, Nicholson A, Rana B, Channick R, Rubin L, O’Connor D, Yuan J. Function of Kv1.5 channels and genetic variations of KCNA5 in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C1837–1853. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00405.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Olson T, Alekseev A, Liu X, Park S, Zingman L, Bienengraeber M, Sattiraju S, Ballew J, Jahangir A, Terzic A. Kv1.5 channelopathy due to KCNA5 loss-of-function mutation causes human atrial fibrillation. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2185–2191. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang Y, Li J, Lin X, Yang Y, Hong K, Wang L, Liu J, Li L, Yan D, Liang D, Xiao J, Jin H, Wu J, Zhang Y, Chen Y. Novel KCNA5 loss-of-function mutations responsible for atrial fibrillation. J Hum Genet. 2009;54:277–283. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ghanshani S, Wulff H, Miller M, Rohm H, Neben A, Gutman G, Cahalan M, Chandy K. Up-regulation of the IKCa1 potassium channel during T-cell activation. Molecular mechanism and functional consequences. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37137–37149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iikuni N, Nakajima A, Inoue E, Tanaka E, Okamoto H, Hara M, Tomatsu T, Kamatani N, Yamanaka H. What’s in season for rheumatoid arthritis patients? Seasonal fluctuations in disease activity. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:846–848. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hu X, Laragione T, Sun L, Koshy S, Jones K, Ismailov I, Yotnda P, Horrigan F, Gulko P, Beeton C. KCa1.1 potassium channels regulate key proinflammatory and invasive properties of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4014–4022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.312264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bartok B, Firestein G. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2010;233:233–255. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pethő Z, Tanner M, Tajhya R, Huq R, Laragione T, Panyi G, Gulko P, Beeton C. Different expression of β subunits of the KCa1.1 channel by invasive and non-invasive human fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:103. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-1003-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Otero M, Goldring M. Cells of the synovium in rheumatoid arthritis. Chondrocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:220. doi: 10.1186/ar2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schett G. Cells of the synovium in rheumatoid arthritis. Osteoclasts. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:203. doi: 10.1186/ar2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]