Abstract

Objective

To conduct an integrative review of empirical studies of loneliness for older people in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Loneliness is a risk factor for older people's poor physical and cognitive health, serious illness and mortality. A national survey showed loneliness rates vary by gender and ethnicity.

Methods

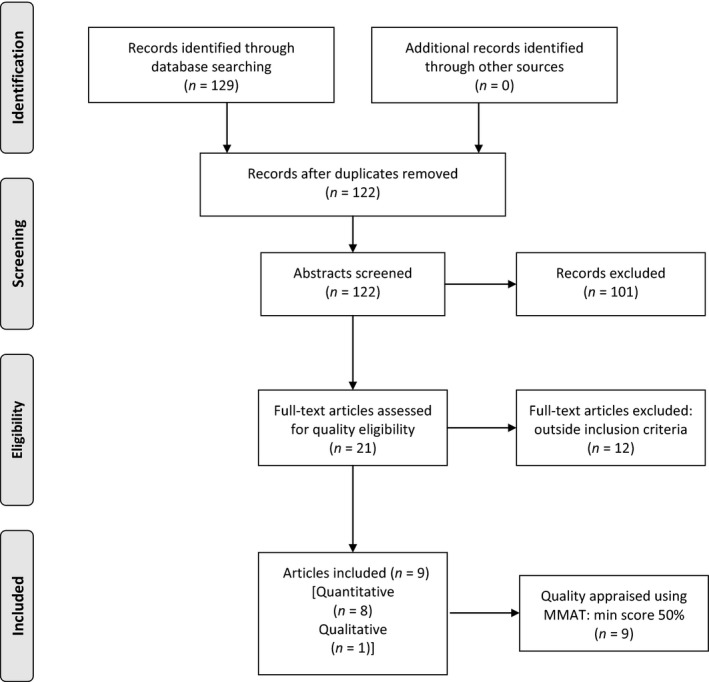

A systematic search of health and social science databases was conducted. Of 21 scrutinised articles, nine were eligible for inclusion and subjected to independent quality appraisal. One qualitative and eight quantitative research articles were selected.

Results

Reported levels and rates of loneliness vary across age cohorts. Loneliness was significantly related to social isolation, living alone, depression, suicidal ideation, being female, being Māori and having a visual impairment. Qualitatively, older Korean immigrants experienced loneliness and social isolation, along with language and cultural differences.

Conclusion

Amongst older New Zealanders loneliness is commonly experienced by particular ethnic groups, highlighting a priority for targetted health and social services.

Keywords: aged, ethnic groups, loneliness, New Zealand, social isolation

Practice Impact: These results indicate a research imperative to increase the number of intervention studies examining how older adults’ loneliness is ameliorated. Further, the results imply that researchers and practitioners ought to be cognisant of the diversity of older adult populations, such as Māori and older immigrants; and to go beyond an ethnic framework to include, for example, gendered and regional differences.

Introduction

Loneliness has been defined as a deficiency in the number or quality of personal, social or community relationships, resulting in feelings of distress, dissatisfaction or detachment 1, 2, 3, 4. In Aotearoa/New Zealand, the 2016 state of the nation's social wellbeing report 5 highlighted that, on average, 10% of those aged 65 to 74 years, and 13% of those aged 75 and older, identified as ‘feeling lonely ‘all of the time’, ‘most of the time’ or ‘some of the time’ in the last four weeks’ (p. 238). Reported loneliness was highest for women, Māori, and Asians. While those aged 65–74 years reported the lowest loneliness rates of all age groups, the results are concerning, as loneliness is associated with depressive symptoms and cognitive decline 6, 7, 8 and has been shown to be a mediating factor between living alone and depression 9. Furthermore, being lonely is a risk factor for mortality, poor health and serious illness across diverse populations 10, 11. Internationally, older people who are lonely are more likely to have poor self‐rated health and functional status, live alone, and have low economic status 11. Already, older adults in Aotearoa/New Zealand represent the highest percentage of one‐person households, with just under a third living alone 12. Of concern, those living in conditions of economic hardship have higher rates of loneliness than younger age groups reporting similar economic hardship levels 13. One of the New Zealand Positive Ageing Strategy goals is to support older people to age in the community, including enabling local solutions to address social isolation 14. However, achieving this ‘ageing in place’ strategic goal may contribute to high loneliness rates and morbidity, particularly for women, as the projected proportion living alone increases as the population ages 12.

Loneliness and social isolation are often interpreted as being the same; however, there is a core difference between the two concepts. Social isolation may be understood as a common cause of loneliness, but a person may be lonely without being socially isolated. For example, Weis 15 emphasised that loneliness is not caused by being alone, but rather the absence of a particular type of relationship or relational provisions. Regardless, undesired social isolation, which is commonly the type of social isolation of interest to researchers, is very closely related to loneliness 1.

A defining feature of Aotearoa/New Zealand's older population is its increasing ethnic diversity (16). The last Aotearoa/New Zealand census indicated 213 ethnic groups residing in the country 16, with an increasing number of older immigrants across diverse ethnicities. As of 2013, nearly two‐thirds (72%) of those aged 65 and over identified as European, around 6% as Māori, 5% as Asian, 2% as Pacific peoples and smaller percentages of others, including Middle Eastern, Latin American, African and other 12. Adding to the complexity, many older New Zealanders identify with more than one ethnic group, particularly Māori, of whom about a third identify with one or more other ethnic groups 12. Demographic projections indicate the ethnic diversity of those aged 65 and over in Aotearoa/New Zealand will increase due to working‐age immigrants ageing in the country, and older immigrants arriving to be reunited with adult children, with many immigrants coming from Asian nations, such as China, India and South Korea; South‐East Asian nations, such as the Phillipines, Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand; and those from the United Kingdom 16. Of social concern is the evidence that older immigrants can be socially isolated and are at high risk of experiencing loneliness 17.

Although features of loneliness are shared across ethnicities and culture, culture is significant in shaping perceptions of loneliness 18, 19. For example, there is a significant correlation between cultural experiences of not belonging, and of being discriminated against, and loneliness 20, 21. Hence, the demography of the country's older and increasingly ethnically diverse population indicates the importance of understanding what is known about older adults and loneliness in Aotearoa/New Zealand, including how loneliness is experienced by disparate peoples.

No systematic review of older New Zealanders’ loneliness research has been previously published. Such country‐specific, foundational knowledge is important as New Zealand's constitutional commitment to Māori as tangata whenua (people of the land), and its public policy, and rapidly changing demographic contexts make it a unique social setting. Establishment of an evidence‐based knowledge will enable identification of gaps in the research and inform social service development aimed at ameliorating loneliness.

The purpose of this systematic, integrative review was to identify and synthesise what is known about loneliness for older people living in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Two supplementary aims were to examine how loneliness has been measured in New Zealand, and what interventions have been used to ameliorate loneliness, in empirical research with older people in Aotearoa/New Zealand.

Methods

An integrative review method was chosen for the systematic and comprehensive search of quantitative and qualitative research literature, as well as the quality appraisal of included articles and synthesis of the results 22. Integrative reviews are widely utilised to provide an auditable and robust synthesis of both quantitative and qualitative literature to provide new insights into phenomena 23. Both quantitative and qualitative perspectives are important when seeking to answer empirical questions consequently, an integrative approach was utilised in the present study. Our approach was guided by Whittemore and Knafl's 22 framework, which provided a rigorous, integrative review process.

Search strategy

The literature search was conducted between 1 December 2015 and 15 January 2016. Initially, the international and local literature were scoped to gain an overview of the topic and inform the search terms to be used. Importantly, terms such as ‘social isolation’ and ‘social network’ were identified as potentially relevant terms in locating the loneliness literature. Health and social science databases were searched, including CINAHL Full Text and Medline through EBSCO Host, Scopus and Proquest Social Sciences. Search terms related to the literature review aim concepts of older adults, loneliness and New Zealand were used, including ‘older people’, ‘elder’, ‘senior’, and ‘geriatric’; ‘social isolation’, and positive alternatives, such as ‘social support’, and ‘social network’; ‘Aotearoa’, the Māori name for New Zealand; and the terms ‘befriending’, ‘phone’, and ‘helpline’ were used to extend the search for intervention studies. Truncations were applied to include various spellings or related terms. Limitations were placed on the search to locate peer‐reviewed, full‐text articles published in English. No limitations were placed on publication date to include a full range of Aotearoa/New Zealand studies. In addition, the reference lists of articles that met the inclusion criteria were searched. Articles were included if: they were peer‐reviewed and reported primary research or secondary data analysis of observational or intervention studies; loneliness and/or social isolation was an outcome measure or a key finding; and participants were older adults, aged 55 or older to account for ethnic variances, and were living in Aotearoa/New Zealand.

Quality appraisal and analysis

Twenty‐one potentially eligible articles were scrutinised using the inclusion criteria. Twelve articles were excluded from eligibility, by consensus agreement (VW & SN), as they did not meet all inclusion criteria. Nine eligible articles 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 were quality‐appraised by VW using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) 33. The MMAT was selected because of its scope to appraise qualitative, quantitative and mixed method research publications. The two MMAT screening questions were applied to each of the nine articles to confirm their suitability for quality appraisal using this tool. A quality eligibility score of 50% or higher was established for inclusion in the integrative review. Scoring was done by allocating 25% for each of four MMAT criteria for the relevant research category. Scores were summed, with 100% being the highest score possible. Then, SN, blinded to the original scores, independently appraised all eligible articles. Scores were collated and showed full agreement. All nine of the eligible articles met the quality inclusion threshold (50% or greater) and were included in the integrative review. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) 34 method was used to document the process, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram 34

Results

Study characteristics

Eight of the nine articles included reported quantitative research 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, and one reported qualitative research 32. Of the quantitative designs, three articles reported on different data from the Health, Work and Retirement Study 26, 27, 28, a large prospective population‐based study, and two articles reported different data from a study with older men 24, 25. The majority reported cross‐sectional data, one reported prospective population data over time, and one reported a randomised controlled trial 30. The qualitative study included used a concept mapping technique to determine key themes from in‐person interview data 32. An integrated summary of the included research is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Integrated results

| Authors | MMAT score (%/4) | Study aim | Study design | Participants age, gender and ethnicity | Outcome measures (no. of items) | Loneliness and social isolation results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative studies | ||||||

| Alpass & Neville 24 | 75% | Investigate the relationships between loneliness, health and depression |

Correlational Cross‐sectional survey. Non‐probability sampling |

Men Urban dwelling, small city Aged ≥65 (65–89 years) 28% live alone (n = 217) |

Self‐rated physical health (score 1–7), SSQ6 (6) R‐UCLALS (12) GDS (30) |

Loneliness was more strongly related to depression than all other factors, including living alone and network size Greater loneliness was significantly associated with higher reported depression |

| Alpass & Neville 25 | 75% | Investigate the correlates of suicidal ideation in non‐clinical sample of older men |

Correlational Cross‐sectional survey |

As above |

Self‐rated physical health, TRHS (53) THS (20) SSQ6 (6) GDS R‐UCLALS (12) TSIQ (30) |

Loneliness was significantly associated with suicidal ideation; but number of, or satisfaction with, social supports were not Those who lived alone were lonelier, and were more depressed |

| La Grow, Alpass, & Stephens 26 | 75% | Test the assumption that those diagnosed with a visual impairment would have less social support and be more socially isolated (lonely) than those who had not |

Sub‐sample of HWR Study_2006 participants 53% response rate to postal survey |

NZ electoral roll representative sample Aged 55–70 (n = 5975 included) Visually impaired (n = 411) Sighted (n = 5564) |

ELSI SF‐36 SPS |

Those with visual impairments had statistically significantly less social support available, and felt more lonely and socially isolated than those without visual impairment |

| Stephens, Alpass, & Towers 27 | 75% | Test the prediction that economic living standards are related to social support and loneliness, and these factors are predicted to affect mental health | Cross‐sectional survey, sub‐sample of HWR Study_2006 (as above) |

Representative population sub‐sample (as above) Aged 55–70 (n = 1720) Māori (n = 131) Non‐Māori (n = 1589) |

SF‐36 ELSI‐SF SPS SWS (single item) |

Women were more likely than men to report greater loneliness and lower living standards Māori were more likely than non‐Māori to report greater loneliness, poor mental health, & lower living standards. Perceived low social support, and more loneliness were associated with poorer mental health Loneliness and social isolation explained 15% of variance in mental health scores, with loneliness having the strongest effect on mental health |

| Stephens, Alpass, Towers, & Stevenson 28 | 75% |

Use an ecological model of ageing to examine the effects of social networks on health. Network types: Wider community (WC), local integrated (LI), private restricted (PR), family dependent (FD) and local self‐contained (LS) |

Postal questionnaire HWR Study_2006 (as above) Wave 1 |

Representative population sample (as above) Aged 55–70 (n = 6662) 36% aged 55–59 29% aged 60–64 25% aged 65–70 |

SF‐36 ELSI‐SF PANT SPS SWS (single item) |

Non‐Māori perceived stronger total social support and felt less lonely than Māori Those with higher living standards were less loneliness and perceived more support Compared with younger ages, the older group were more likely to perceive less social support, and less likely to report loneliness Women reported more social support and were more likely to report loneliness Loneliness was moderately associated with total social support, yet contributed more strongly than social support to physical and mental health variance Loneliness and social provisions were positively related to WC and LI networks, and negatively to PR, FD and LS networks |

| La Grow, Towers, Yeung, Alpass, & Stephens 29 | 75% | Investigate the rate and degree of loneliness, and contribution to perceived quality of life for visually impaired older adults | Secondary analysis of survey data, wave 2 of NZLSA |

Older adults aged ≥65 (n = 2683) Visually impaired (n = 315) Sighted (n = 2368) |

Scored visual impairment (single item) dJGLS PQOL ELSI‐SF SF‐12v2 |

Over a half of the visually impaired, and over a third of the sighted group felt lonely The visually impaired were significantly lonelier, and almost twice as likely to be severely lonely, than the sighted group Increasing loneliness was directly, negatively, and significantly associated with economic well‐being, mental health, satisfaction with life and perceived quality of life (PQOL) Social loneliness made a unique, significant contribution to PQOL, while emotional loneliness did not |

| Robinson, MacDonald, Kerse, & Broadbent 30 | 75% | Explore how the psychosocial effects of companion robot, Paro, compared with a control group over 12 weeks |

Randomised controlled trial Experimental group |

Aged care residents Aged 55–100 (n = 40) 13 men 19 scored ≤6 on AMT |

R‐UCLALS (V3) GDS QoL‐AD |

Significant between‐group change in loneliness scores, after adjusting for baseline scores Experimental group (companion robot) mean loneliness score decreased (−5.38); control group (usual activities) mean loneliness score increased (2.29) over time No significant between‐group changes in depression or quality of life, after adjusting for baseline scores in both measures |

| La Grow, Neville, Alpass, & Rogers 31 | 50% | Identify the rate and degree of loneliness, and determine the impact on self‐reported mental and physical health | Cross‐sectional survey |

Community‐dwelling older adults Aged ≥65 (65–98 years) 57% women 62% married or partnered (n = 332) |

dJGLS SF‐36 |

Over half were lonely, including 44% moderately and 8% severely lonely No significant difference for sex, marital status or age Loneliness was significantly related to poorer physical and mental health |

| Qualitative | ||||||

| Park & Kim 32 | 75% | Explore the immigrant experiences of older Koreans and their intergenerational family relationships | Qualitative methodology, phenomenological based interviewing |

Korean immigrants, older adults on arrival in NZ Aged 71–88 (n = 10) Key informants (n = 20), including co‐ethnic community members and health professionals |

Semistructured interviews. Concept mapping to identify themes |

Others’ discriminatory attitudes intensified feelings of not belonging and loneliness, like ‘living in an invisible prison’ English language was the most difficult life barrier, limiting social networks Men more likely to feel demoralised, with nothing to do inside or outside the home Intergenerational relationships became complex and difficult Less participation in host society due to language and cultural unfamiliarity, becoming isolated and lonely |

Key for quality evaluation: MMAT, mixed methods appraisal tool. Key for studies: HWR Study, Health, Work and Retirement Study; NZLSA, New Zealand Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Key for measures: dJGLS, de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale (11 items); ELSI/ ELSI‐SF, New Zealand Economic Living Standards Indicator/Short Form; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale (15 or 30 items); PANT, Practitioner Assessment of Network Type (social engagement measure); PQOL, Perceived Quality of Life; QoL‐AD, Quality of Life for Alzheimer's Disease; R‐UCLALS, University of California Los Angeles Loneliness Scale; SF‐12v2, Health Survey‐Short Form, Volume 2 (12 items); SF‐36 Health Survey (36 items; 8 subscales); SPS, Social Provisions Scale (single item of one's feelings of isolation); SSQ6, Social Support Questionnaire (6 items); SWS, NZ Social Wellbeing Survey 2004, Question 9 (single item); THS, The Hopelessness Scale (20 true/false); TRHS, The Revised Hassles Scale (53 items); TSIQ, The Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (30 items).

Definitions of loneliness

Loneliness was defined, generally, in all the articles, as a subjective phenomenon, based upon people's perceptions or experiences of a deficiency in their social relationships. However, the definitions differed slightly, and five of the nine articles critically examined what loneliness meant 24, 27, 28, 29, 31. Two 27, 28 closely related loneliness to social isolation, drawing upon Rook's 35 definition of loneliness as perceived social isolation that is emotionally painful. Alpass and Neville 24 differentiated between loneliness and social isolation: the former being an internal negative emotion, while the latter is associated with social support factors which are external to the person. This distinction means that loneliness can occur in ‘the presence and absence of social contact’ 24. The remaining two articles 29, 31 in this grouping considered loneliness, similarly, in terms of people's perceived quality of relationships, rather than the frequency or quantity of their occurrence. As mentioned above, social isolation is not necessarily a component of loneliness.

Measurements of loneliness

A variety of measurement tools were reported in the eight quantitative articles, including multi‐item, standardised questionnaires, and one single‐item measure. The measures’ purpose, constructs, items, scoring and psychometric properties are summarised in Table 2. Two studies used versions of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale. Robinson et al. 30 used the revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Version 3 36. For example, participants rated whether they ‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘sometimes’ or ‘always’ felt they ‘have no one to talk to’. Alpass and Neville 24, 25 used the 12‐item revised UCLA Loneliness Scale 37, with participants rating their subjective emotional states, such as ‘I am “almost never”, “not often”, “sometimes”, “often” or “almost always” unhappy being so withdrawn’.

Table 2.

Common loneliness measures used with older adults in New Zealand

| Characteristics | R‐UCLA Loneliness Scale | de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale | NZ Social Wellbeing Survey question | Social Provisions Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designed for | Measuring young adult, adult, and older adult loneliness | Measuring adult and older adult loneliness | Measuring population loneliness and isolation in NZ Government's Social Wellbeing Questionnaire | Measuring the degree to which children's to older adults’ social relationships provide various dimensions of social support |

| Construct |

Loneliness is subjective, as affect ‘a unidimensional emotional response (thus affective state) to a discrepancy between desired and achieved levels of social contact’ [38; p.283] |

Loneliness is subjective, as cognitive. Loneliness as a cognitive construct as ‘a situation experienced by the individual as one where there is an unpleasant of inadmissible lack of (quality of) certain relationships’ [1; p.73] |

Loneliness and isolation as indicators of social connectedness 41 |

Social provision as perceived support measured as Attachment, Reassurance of Worth, Reliable Alliance, Guidance, and Opportunity for Nurturance Social support is a protective factor |

| Items, domains, & scoring |

Version 3_20 item scale

10 in non‐lonely, positive direction and 10 in lonely, negative direction 12‐item short form Developed for use with large‐scale population studies Respondents Indicate how often they feel the way described in each item Scoring 4‐point scale (1) never, (2) rarely, (3) sometimes, (4) often. Positive items are reverse coded. Simple sum of scores; Higher score = more lonely Criticised for measuring social dimension only |

11‐item scale

6‐item emotional subscale (negatively worded) 5‐item social subscale (positively worded) Respondents Indicate the extent to which statements apply to their current situation Scoring Original scale 4‐point scale (1) Yes! (2) Yes, (3) No, (4) No! Or revised 3‐point scale (1) Yes, (2) More or less, (3) No. Collapse 1 and 2 for negatively worded and 2 and 3 for positively worded statements Sum of scores Higher score = more lonely Used as a global, unidimensional measure of loneliness, or as separate emotional and social subscales |

Single item Q9

‘How often in the last 12 months have you felt lonely or isolated?’ Scoring 5‐point scale (1) Always, (2) Most of the time, (3) Sometimes, (4) Rarely, (5) Never Lower score = more socially disconnected/lonely |

24‐item scale

4 items for each of the six subscales 12 describes the presence of a type of support 12 describes the absence of a type of support Respondents Indicate the extent to which each statement describes his/her current social network Scoring 4‐point scale (1) Strongly disagree, (2) Disagree, (3) Agree, (4) Strongly agree Sum all items after reverse scoring of negatively worded items Subscales can be summed Higher score = greater degree of perceived support |

| Psychometric properties |

Version 3

Standardised for use with older adults, however evaluated as limited utility for assessing loneliness for older adults Reliability Internal consistency: Good, coefficients 0.89―0.94 Test–retest: 0.73 over a one year period CFA Multidimensional 4‐factor CFA = weak‐acceptable. Ranged 0.179 (item 4) to 0.718 (item 6); all statistically significant (P < 0.001). CFI = 0.976, TLI = 0.961 |

Good utility for use as unidimensional scale with older adults Internal consistency Good, coefficients 0.80―0.90, particularly with older adults Reliability and validity Robust of the overall scale, and the social, and emotional subscales Homogeneity of the scale is not very strong, therefore considered bidimensional for social and emotional factors CFA Unidimensional and multidimensional 2‐factor utility. Marginally acceptable. Ranged 0.495 (item 10) to 0.751 (item 6); all statistically significant (P < 0.001) |

Not available Single measures may be readily affected by social desirability concerns 39 Used in The Social Report, Ministry of Social Development Results comparable to national governmental well‐being surveys |

Normed data for older adults Reliability Internal consistency: >0.70 across all provisions Test–retest: coefficient 0.37 to 0.66 Validity Predictive: of adult loneliness, depression & health status Convergent: total score for older adults correlated 0.28 to 0.31 (P < 0.05) with life satisfaction, loneliness and depression, as well as with measures of social networks and satisfaction with types of social relationships Discriminant: Intercorrelations among the six provisions 0.10 to 0.51 (mean 0.27) |

| Administrative burden | Implemented face‐to‐face, telephone, self‐report survey. Some training required |

Implemented face‐to‐face, telephone, self‐report survey Some training required |

Implemented face‐to‐face, telephone, self‐report survey No training required |

Interviewer‐administered Non‐copyrighted, openly available Minimal training required |

| Respondent burden | Time required: 5 minutes |

Time required: <5 minutes 6‐item short form available |

Minimal respondent burden Time required: <1 minute |

Moderate respondent burden Time required: 5 minutes |

CFA, confirmatory factor analysis; CFI, comparative fit index; NZ, New Zealand; R‐UCLALS, University of California Los Angeles Loneliness Scale.

Two studies 29, 31 used the de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale 40, for which loneliness is understood as a cognitive construct, perceived socially and emotionally. Participants were asked whether each of statements apply to their lives now, such as ‘I miss the pleasure of the company of others’ by choosing between ‘Yes’, ‘More or less’, or ‘No’. Different data from the Health, Work and Retirement Study, a prospective, longitudinal study with 6662 people aged 55 and over, were reported across three articles 26, 27, 28. The main study used a single‐item loneliness question from the 2004 New Zealand Social Wellbeing Survey, reported in the ‘state of the nation's wellbeing’ report 41; ‘How often in the last 12 months have you felt lonely or isolated?’ In addition to measuring loneliness directly, the Health, Work and Retirement Study used the Social Provisions Scale 42 which has six subscales for social supports from social relationships 43. While the Social Provisions Scale is not a direct measure of loneliness, the Attachment subscale includes the extent of ‘feeling of closeness with anyone’ in social networks. Older adults’ total scores have been shown to significantly (P = <0.05) correlate with loneliness, life satisfaction and depression 42, 44, and the measure is reliable for use with low income and minority populations 44.

Cultural and social diversity

Aotearoa/New Zealand's ethnically and culturally diverse population was somewhat represented in the studies, which reported data for older Korean immigrants 32, Māori, and non‐Māori, which would have included ethnicities in addition to Caucasian 27, 28, and those who lived with, and without, significant visual impairment 26, 29.

Older immigrants

One study investigated older immigrants’ experiences of living in Aotearoa/New Zealand society. Park and Kim's 32 Korean participants, who had immigrated to New Zealand later in life, disclosed experiencing loneliness and social isolation, interpreted as feeling invisible in the community. The narrative data described being a late life immigrant as impacting significantly on social networks, changed intergenerational family and societal relationships, and the separations inherent in living as a transnational family. English language was a barrier to social inclusion. Older immigrants may have participated in the two large cohort studies, the Health, Work and Retirement Study 26, 27, 28, and the New Zealand Longitudinal Study of Ageing 29, but such demographic data were not reported.

Older Māori

One prospective longitudinal study measuring loneliness, the Health, Work and Retirement Study, included Māori aged 55 to 70 years. Results showed that older Māori were more likely to report feeling lonely and had weaker perceptions of total social support than non‐Māori 27, 28. The distal effects of colonisation, poorer health, living standards and lower socio‐economic status for Māori may have contributed to these discrepancies 28. Disadvantaged cohorts, such as minority groups, or lower socio‐economic groups, often reported less perceived support and increased loneliness 28. Family and locally integrated social networks were found to be important to older Māori 28. For example, Stephens et al. 28 found that older Māori value family and locally integrated networks. Perceived deficits in such relationships may have had a more significant association with loneliness due to their cultural and personal importance. These results suggest the importance of understanding culturally important relationships that enable cultural expression, and greater understanding of how such relationships affect loneliness for older Māori.

Older people with visual impairment

Being visually impaired relates to older adults’ social and emotional loneliness 29, and to the depth of attachment in social relationships 26. Those with visual impairment were significantly more likely to report greater loneliness and social isolation and have less social support available, compared with those without visual impairment. La Grow et al. 29 found decreased economic well‐being, mental health, satisfaction with life and perceived quality of life were all associated with increasing levels of loneliness. Interestingly, social loneliness, but not emotional loneliness, was found to have a statistically significant negative relationship with perceived quality of life. That is, participants’ social loneliness scores increased as their quality of life scores decreased. In particular, social loneliness, or a perceived deficit in the size and extent of one's social circle, was an important consideration for the visually impaired population 26, 29. These data highlight the importance of considering people with visual impairment as a subgroup at considerable risk of loneliness, potentially due to their interrupted social participation.

Loneliness and health

The relationship between loneliness and health and well‐being was consistently reported, with loneliness being negatively associated with physical health, mental health and quality of life. In other words, greater loneliness was related negatively to poorer health and quality of life. In turn, loneliness was significantly, positively related to depression 24, 28, 29, 31. Furthermore, levels of loneliness and depression were significantly correlated with suicidal ideation for New Zealand men aged 65 and over, representing a significant health issue for older men 25. In contrast, the only loneliness intervention study 30 included in this integrative review found significant between‐group effects when baseline scores were controlled for loneliness (=0.03), but not for depression or self‐rated quality of life. The 40 older residential care participants were randomly allocated to either the experimental group (n = 20), with individuals allocated time to engage with a small, interactive seal robot (Paro), or the control group (n = 20), with individuals participating in the usual activity program, which included bus trips and crafts sessions, for 12 weeks. The experimental group loneliness scores reduced (mean change = −5.38), compared with an increased mean loneliness score (+2.29) for the control group. The relatively short, three‐month, intervention may have accounted for the decrease in the experimental group depression scores not reaching statistical significance.

Qualitatively, Korean immigrants described diminished mental health, as illustrated by one participant's description of immigrants living like caged birds, ‘isolated and depressed’ 32. Additionally, poor physical health was found to be negatively associated with loneliness, and positively associated with limited social support 28, 31. That is, greater loneliness and diminished social support were both strongly related to poor physical health for older New Zealanders. While this relationship does not show loneliness causes poor health, the results were consistent with international evidence and suggest ameliorating loneliness may positively influence older adults’ physical and health.

Discussion

Aotearoa/New Zealand gerontology research on loneliness appears to be increasing, with over half of the articles included in this integrative review being published within the last five years. The advancement in local research knowledge on the prevalence of older people's loneliness is promising. However, as only one intervention study was located, research is now needed to establish valid ways of preventing and/or ameliorating loneliness. Nonetheless, the Aotearoa/New Zealand data add to an expanding body of international literature on this important worldwide health issue. Loneliness is a significant health issue for older New Zealanders and, as evidenced in this integrative review, disproportionately impacts older Māori, and people with visual impairments. Furthermore, the results of this review indicate the importance of differentiating loneliness and its effects for diverse subgroups in Aotearoa/New Zealand society. The older Korean immigrants’ qualitative accounts of loneliness and barriers to social inclusion align with the international literature on loneliness associated with discrimination and a sense of not belonging 21.

Beyond understanding how loneliness impacts Aotearoa/New Zealand's diverse older adult populations, research is needed to effectively predict and prevent, and to identify and test evidence‐based interventions and community services directed at ameliorating older adults’ loneliness. The use of companion robots in residential aged care is promising, but the small sample in the study reviewed limits the generalisability of the intervention at this point in time. However, these results are in line with international research evidencing the positive psychosocial effects of older adults’ engagement with companion robots 45. No Aotearoa/New Zealand studies were found that tested the effectiveness of community‐based group programs, or individual telephone, mentoring or letter companion services aimed at ameliorating older adults’ loneliness. A systematic search of intervention research reported in 2014 found loneliness was significantly reduced in one, of nine, community‐based group intervention studies, one, of three, one‐to‐one mentoring studies, and three, of six, studies using new technologies including web‐based interventions and computer games 46. These results suggest that one‐to‐one interventions may be more likely to be effective. Further research on social connectedness, relationship quality and loneliness as experienced by diverse older adult populations in Aotearoa/New Zealand is warranted to inform the translation of findings into effective interventions. In particular, developing a more sophisticated understanding of what predicts loneliness in people's later years would enable the early implementation of culturally‐centred services or interventions in place earlier for younger cohorts.

Published research on older adults’ loneliness in Aotearoa/New Zealand has, to date, been predominantly observational and quantitative in nature, including cross‐sectional studies and two large prospective, longitudinal studies. Ultimately, understanding the predictive risk factors for loneliness will enable the development of early intervention programs and reduce the loneliness burden experienced by older adults. Despite the gaps in knowledge regarding evidence‐based interventions and services, the results of this integrative review show that loneliness is significantly and positively associated with poor physical and mental health for diverse people in Aotearoa/New Zealand, and worthy of further knowledge development. Further, the findings of this review highlight the importance of understanding the needs of specific populations, such as older immigrants, for whom there is an increased risk of loneliness.

Despite the limited scope of empirical evidence within Aotearoa/New Zealand, the results of the reviewed studies with minority groups are consistent with the wider literature. There is consistent evidence that older Chinese, Indian and Korean 47, and older Filipino 48 immigrants experience social isolation and loneliness, as well as diminished social relationships and quality of life 49. The discrepancies in loneliness rates between a minority indigenous population, and a majority population, as for older Māori and non‐Māori, in this study, may be somewhat explained by the data indicating that older Māori in Aotearoa/New Zealand face significant inequalities, have poorer health and have higher mortality rates at younger ages, which is largely mediated by socio‐economic status 50. The results of this review suggest that older Māori are an important population to target for understanding the interplay of culture, colonisation and loneliness. Such understandings would enable the implementation of culturally relevant interventions to ameliorate against loneliness for older Māori, as Aotearoa/New Zealand's indigenous population.

Limitations

This integrative review did not include grey literature or theoretical literature. With the recent increase in research on loneliness, it is likely more manuscripts were in process of publication, and therefore not located. A variety of loneliness measurement tools were used in the reviewed articles, making it difficult to synthesise some of the results. A limited number of Aotearoa/New Zealand studies on diverse older adults’ loneliness were retrieved. However, all articles that met the review's inclusion criteria also met the quality appraisal cut‐off level and were therefore included. Of the nine articles reviewed, three draw on loneliness data from a large population study, and two from a study of older men. Yet all are included as they analyse and report different data. Lastly, there was some difficulty in choosing a quality appraisal tool that allowed for comparative appraisal of published qualitative and quantitative research. Because the MMAT uses four appraisal criteria only to score each article, the instrument's sensitivity is somewhat limited.

Conclusion

There is an apparent increase in Aotearoa/New Zealand gerontological research on understanding, and potentially ameliorating, older people's experiences of loneliness, and its negative impact on physical and mental health. Collectively, the findings demonstrate the importance of loneliness as a social and health issue for older people in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Significant associations between loneliness and poorer physical and mental health, and social connectedness are evident. Moreover, particular populations may be at increased risk of loneliness, and/or experience loneliness differently from other groups within society. These groups included older Māori, Asian immigrants, and people with visual impairments. The pattern suggests minority groups, and those who face discrimination within communities, may be important populations for future research on loneliness. Additionally, these findings heighten the need for Aotearoa/New Zealand health and social services to prioritise the detection and amelioration of loneliness when working with diverse populations of older people. Further research into successful interventions for reducing loneliness is needed in Aotearoa/New Zealand, including the effectiveness of a range of companion services. Importantly, this review suggests the next generation of research should move beyond measuring loneliness, to develop, test and implement effective interventions to prevent or ameliorate loneliness for diverse populations of older people.

Acknowledgements

The Research and Innovation Office, Auckland University of Technology, granted a Small Grants Award for a research assistant to complete this project, for the purpose of reporting the outcomes to the Silver Line Charitable Trust of New Zealand, a newly registered charitable trust to help address older adult loneliness in New Zealand. The Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences has a Memorandum of Understanding with the Silver Line Charitable Trust Board to support research on older adult loneliness to inform an evidence‐based service. L White is a member of the Silver Line Charitable Trust Board; VA Wright‐St Clair was a member and S Neville was an affiliate member at the time the study was conducted. The Trust Board, as a body, in no way influenced the project design or report.

References

- 1. de Jong Gierveld J. A review of loneliness: Concept and definitions, determinants and consequences. Review of Clinical Gerontology 1998; 8: 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peplau LA, Perlman D. Toward a social psychology of loneliness In: Duck SW, Gilmour R, eds. Personal Relationships. 3 Personal Relationships in Disorder. London: Academic Press, 1981: 3–55. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andersson L. Loneliness research and interventions: A review of the literature. Ageing and Mental Health 1998; 2: 264–274. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Killeen C. Loneliness: An epidemic in modern society. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1998; 28: 762–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ministry of Social Development . The Social Report 2016: Te Pūrongo Oranga Tangata. Wellington: Ministry of Social Development, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cohen‐Mansfield J, Hazan H, Lerman Y, Shalom V. Correlates and predictors of loneliness in older‐adults: A review of quantitative results informed by qualitative insights. 2015; IPA: 1‐20. International Psychogeriatrics 2015; 28: 557–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhong B‐L, Chen S‐L, Conwell Y. Effects of transient versus chronic loneliness on cognitive function in older adults: Findings from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2016; 24: 389–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heikkinen R, Kauppinen M. Depressive symptoms in late life: A 10‐year follow‐up. Archives of Gerontology & Geriatrics 2004; 38: 239–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Park NS, Jang Y, Lee BS, Chiriboga DA. The relation between living alone and depressive symptoms in older Korean Americans: Do feelings of loneliness mediate? Aging and Mental Health 2017; 21: 304–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all‐cause mortality in older men and women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013; 110: 5797–5801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ministry of Social Development . The Social Report: Te Purongo Oranga Tangata. Wellington: Ministry of Social Development, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Statistics New Zealand . 2013 Census QuickStats About People Aged 65 and Over. Wellington: Statistics New Zealand, 2015. [Cited 27 February 2016.] Available from URL: http://www.stats.govt.nz

- 13. Statistics New Zealand . Loneliness in New Zealand: Findings from the 2010 NZ General Social Survey. Wellington: Statistics New Zealand, 2013. [Cited 27 February 2016.] Available from URL: http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/people_and_communities/older_people/loneliness-in-nz-2010-NZGSS/loneliness-in-nz.aspx

- 14. Office for Senior Citizens . 2014 Report on the Positive Ageing Strategy Wellington: Office for Senior Citizens, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weiss RS. Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation. London: MIT Press, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Statistics New Zealand . 2013 Census QuickStats About Culture and Identity. Wellington: Statistics New Zealand, 2014. [Cited 27 February 2016.] Available from URL: http://www.stats.govt.nz

- 17. Wu Z, Penning M. Immigration and loneliness in later life. Ageing and Society 2015; 35: 64–95. [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Staden W, Coetzee K. Conceptual relations between loneliness and culture. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 2010; 23: e524–e529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. deJong Gierveld J , dervan Pas S , Keating N. Loneliness of older immigrant groups in Canada: Effects of ethnic‐cultural background. Journal of Cross‐Cultural Gerontology 2015; 30: 251–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu D, Yu X, Wang Y, Zhang H, Ren G. The impact of perception of discrimination and sense of belonging on the loneliness of the children of Chinese migrant workers: A structural equation modeling analysis. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 2014; 8: 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Switaj P, Grygiel P, Anczewska M, Wciórka J. Experiences of discrimination and the feelings of loneliness in people with psychotic disorders: The mediating effects of self‐esteem and support seeking. Comprehensive Psychiatry 2015; 59: 73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2005; 52: 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Neville S, Napier S, Adams J, Wham C, Jackson D. An integrative review of the factors related to building age‐friendly rural communities. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2016; 25: 2387–2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Alpass F, Neville S. Loneliness, health and depression in older males. Aging and Mental Health 2003; 7: 212–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alpass F, Neville S. Suicidal ideation in older New Zealand males (1991–2000). International Journal of Men's Health 2005; 4: 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- 26. La Grow S, Alpass F, Stephens C. Economic standing, health status and social isolation among visually impaired persons aged 55 to 70 in New Zealand. Journal of Optometry 2009; 2: 155–158. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stephens C, Alpass F, Towers A. Economic hardship among older people in New Zealand: The effects of low living standards on social support, loneliness, and mental health. New Zealand Journal of Psychology 2010; 39: 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stephens C, Alpass F, Towers A, Stevenson B. The effects of types of social networks, perceived social support, and loneliness on the health of older people: Accounting for the social context. Journal of Aging and Health 2011; 23: 887–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. La Grow S, Towers A, Yeung P, Alpass F, Stephens C. The relationship between loneliness and perceived quality of life among older persons with visual impairments. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness 2015; 109: 487–499. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Robinson H, MacDonald B, Kerse N, Broadbent E. The psychosocial effects of a companion robot: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2013; 14: 661–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. La Grow S, Neville S, Alpass F, Rodgers V. Loneliness and self‐reported health among older persons in New Zealand. Australasian Journal on Ageing 2012; 31: 121–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Park H‐J, Kim CG. Ageing in an inconvenient paradise: The immigrant experiences of older Korean people in New Zealand. Australasian Journal on Ageing 2013; 32: 158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M et al. Proposal: A Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool for Systematic Mixed Studies Reviews. Montreal, QC: Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, 2011. [Cited 27 February 2016.] Available from URL: http://www.webcitation.org/5tTRTc9yJ [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 2009; 151: 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rook KS. Towards a more differentiated view of loneliness In: Duck SW, ed. Handbook of Personal Relationships: Theory, Research and Interventions. New York, NY: Wiley, 1989: 571–589. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment 1996; 66: 20–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maxwell G, Coebergh B. Patterns of loneliness in a New Zealand population. Community Mental Health in New Zealand 1986; 2: 48–61. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Green LR, Richardson DS, Lago T, Schatten‐Jones EC. Network correlates of social and emotional loneliness in young and older adults. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2001; 27: 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Russell D, Peplau LA, Ferguson ML. Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment 2010; 42: 290–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. de Jong Gierveld J, van Tilburg T. Manual of the Loneliness Scale. Amsterdam: Department of Social Research Methodology, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 1999. [Cited 27 February 2016.] Available from URL: http://dspace.ubvu.vu.nl/bitstream/handle/1871/18954/1999%20dJG%20vT%20Loneliness%20manual.pdf?sequence=2 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ministry of Social Development . The Social Report. Wellington: Ministry of Social Development, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Perera HN. Construct validity of the Social Provisions Scale: A bifactor exploratory structural equation modeling approach. Assessment 2016; 23: 720–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cutrona CE, Russell D. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress In: Jones WH, Perlman D, eds. Advances in Personal Relationships. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1987: 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cutrona CE, Russell D. Social Provisions Scale. [Cited 12 June 2016.] Available from URL: http://www.ucp.pt/site/resources/documents/ICS/GNC/ArtigosGNC/AlexandreCastroCaldas/26_CuRu87.pdf

- 45. Bemelmans R, Gelderblom GJ, Jonker P, de Witte L. Socially assistive robots in elderly care: A systematic review into effects and effectiveness. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2012; 13: 114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hagan R, Manktelow R, Taylor BJ, Mallett J. Reducing loneliness amongst older people: A systematic search and narrative review. Aging and Mental Health 2014; 18: 683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wright‐St Clair VA, Nayar S. Older Asian immigrants’ participation as cultural enfranchisement. Journal of Occupational Science 2016; doi: 10.1080/14427591.2016.1214168 (forthcoming). [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tiamzon TJ. Circling back: Reconstructing ethnic community networks among aging Filipino Americans. Sociological Perspectives 2013; 56: 351–375. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mukherjee AJ, Diwan S. Late life immigrations and quality of life among Asian Indian older adults. Journal of Cross‐cultural Gerontology 2016; 31: 237–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jatrana S, Blakely T. Ethnic inequalities in mortality among the elderly in New Zealand. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 2008; 32: 437–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]