Abstract

2013 saw the National Health Service (NHS) in England severely criticized for providing poor quality despite successive governments in the previous 15 years, establishing a range of new institutions to improve NHS quality. This study seeks to understand the contributions of political and organizational influences in enabling the NHS to deliver high‐quality care through exploring the experiences of two of the major new organizations established to set standards and monitor NHS quality. We used a mixed method approach: first a cross‐sectional, in‐depth qualitative interview study and then the application of principal agent modeling (Waterman and Meier broader framework). Ten themes were identified as influencing the functioning of the NHS regulatory institutions: socio‐political environment; governance and accountability; external relationships; clarity of purpose; organizational reputation; leadership and management; organizational stability; resources; organizational methods; and organizational performance. The organizations could be easily mapped onto the framework, and their transience between the different states could be monitored. We concluded that differing policy objectives for NHS quality monitoring resulted in central involvement and organizational change. This had a disruptive effect on the ability of the NHS to monitor quality. Constant professional leadership, both clinical and managerial, and basing decisions on best evidence, both technical and organizational, helped one institution to deliver on its remit, even within a changing political/policy environment. Application of the Waterman–Meier framework enabled an understanding and description of the dynamic relationship between central government and organizations in the NHS and may predict when tensions will arise in the future. © 2016 The Authors. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Keywords: health care quality, setting standards, health care regulation

Background

2013 became what many commentators described as the worst year in the history of the English National Health Service (NHS). A series of national reports were published and television exposés were broadcast, culminating in the Francis Enquiry (Francis, 2012), which highlighted the poor quality of care in certain hospitals and care homes. Coalition health ministers talked about “a poor culture” and “acceptance of the mediocre” by many workers in the NHS (Campbell, 2013). Interestingly, much of the negative publicity concentrated on the NHS monitoring of quality and the responsible institution rather than the failing hospitals themselves. Such was the outcry over the role of the Care Quality Commission (CQC), the organization responsible for monitoring national quality at that time, that new senior staff were appointed and a change in its approach to inspection was announced in the House of Commons by the Prime Minister (BBC news Stafford 2013). Investigating the background to how this could happen, through tracing the evolution of the organizations established to set and monitor quality standards, is important in order to understand the genesis of quality disasters such as Stafford and to help prevent them.

Improving the efficiency as well as quality of the services that the NHS provides has been a main focus for successive UK governments over the last 20 years. While there have been many approaches to “quality improvement” drawing on many disciplines, the underlying dominant paradigm has increasingly become the setting and monitoring of national standards through targets in various forms. It is not only in health that this approach has been applied, as local authorities and education have also been subjected to ever more stringent monitoring regimes. This approach has been heralded as part of the new public management approach to managing health services, where the tension between centralized control versus local autonomy driven by market forces has been played out (Klein, 2010). In England the emphasis is still on a purchaser provider split which means that the responsibility for standard‐setting and quality monitoring has been given to independent bodies often called quangos (quasi‐autonomous non‐governmental organisations) in the UK. A quango is an organization to which government has devolved power. In the United Kingdom this term covers different “arm's‐length” government bodies, including “non‐departmental public bodies, non‐ministerial departments, and executive agencies” (Lewis et al., 2006). This new approach to encouraging health care quality was outlined by the incoming Labour government in its 1997 white paper “The New NHS, modern and dependable” (Department of Health, 1997) which created a national framework for quality based on the setting and monitoring of national standards. To facilitate this approach a range of quangos were created and have disappeared over the years. Two new organizations were established that were key to the functioning of the new approach and have survived albeit in differing guises. The Commission for Healthcare Improvement (CHI) was the first NHS quality‐monitoring organization and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), was to “promote clinical and cost effectiveness by producing clinical guidelines and audits, for dissemination throughout the NHS” (Horton, 1999). By 1999, both CHI and NICE were operating. However, five years after its establishment CHI was subsumed by the Healthcare Commission, officially the Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection, CHAI (Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) Act [Link]). CHAI was in existence for another five years until its responsibilities were taken over by the CQC in 2009 (Health and Social Care Act, [Link] (Commencement No. 9, Consequential Amendments and Transitory, Transitional and Saving Provisions) Order 2009). Over the same period, NICE also saw changes with an expansion of its original remit and changes to its formal title and status. In 2005 it became the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, having taken over the public health functions after the Health Development Agency was disbanded (Littlejohns and Kelly, 2005). Then, as part of the legislation enacting the NHS reforms and having been given new responsibility to produce guidance in social care, NICE was reconstituted as a non‐departmental public body called the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Lancet, 2013). Throughout these developments the institute retained the NICE acronym, reflecting the importance of its “brand recognition” (Morris, 2009). It is apparent that both were subject to political direction and organizational change. During this period NICE, despite much public outcry over some of its decisions, has appeared to thrive and develop an international reputation while successive quality‐monitoring organizations have struggled to establish themselves. Even now the latest manifestation of the monitoring organization has received challenging reports from government bodies (Public Accounts committee report into the CQC, 2015) and criticism from professional bodies (Chief Inspector 2015).

From a political science perspective these quangos form the classical “agents” and the Department of Health the “principal” in principal agent modeling, which has dominated recent academic analysis of the relationship between bureaucracies and elected officials. Waterman and Meier have broadened the concept by creating a dynamic framework based on their thesis that goal conflict and information asymmetry (the main stays of principle agent theory) are not necessarily constant (Waterman 1998).

In order to better understand the role of central government, and the relationship with the quangos that were established to improve quality, we have undertaken a two‐stage investigation. We undertook a series of interviews with key players to identify the key features relevant to a principle‐agent model, and then using these characteristics we mapped the institutions to the Waterman, Meier expanded model.

Methods

Interview

We conducted an interview study using a conventional qualitative content analysis approach (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). Our research approach comprised five main elements: (i) unstructured data collection using open‐ended interview questions; (ii) multiple, independent data judges throughout data analysis; (iii) judges arriving at consensus about the meaning of data; (iv) an auditor to check the work of the data judges; and (v) an analysis that coded interview data into categories, provided a description of each category and examined discrepancies across interviews.

Setting and participants

We used a purposive (expert‐sampling) approach to identify individuals with significant expertise or experience at senior‐management level in one or more of the organizations involved in NHS standard‐setting or quality‐monitoring. Eleven expert informants (including senior managers in the relevant organizations) were selected and invited by email to participate. All 11 agreed to participate and completed their interviews in full. Our participants were:

Professor Sir Michael Rawlins (Chairman of NICE, 1999–2012)

Sir Andrew Dillon (Chief executive of NICE, 1999–present)

Professor David Haslam (Chairman of NICE, 2013–present; Healthcare Commission: National Clinical Adviser, 2005–2009; Care Quality Commission: National Professional Adviser, 2009–2013)

Professor Sir Ian Kennedy (Chairman of the Healthcare Commission, 2004–2009)

Andy McKeon (Director General of Policy and Planning, Department of Health, 2002; Managing Director, Health, Audit Commission, 2003–2012; Non‐executive Director of NICE, 2009–present)

Dr. Linda Patterson (Medical Director of Commission for Health Improvement, 1999–2004)

Dr. Peter Homa (Chief Executive of Commission for Health Improvement, 1999–2004)

Andrea Sutcliffe (Deputy Chief Executive of NICE, 2001–2007; Chief Care Inspector for Social Care, Care Quality Commission, 2013 – present)

Professor Albert Weale (Professor of Political Theory and Public Policy at University College London; Chair of the Nuffield Council for Bioethics 2007–2012; Author of “Democratic Justice and the Social Contract”)

Professor Sir Michael Richards (Chief Inspector of Hospitals Care Quality Commission 2013–present)

Cynthia Bower (Chief Executive of Care Quality Commission, 2009–2012)

Procedures

An experienced medical journalist (Polly Newton) conducted in‐depth (unstructured) face‐to‐face interviews in participants' private offices. Interviews lasted 35–88 min (mean 62 min) and were recorded and transcribed verbatim. We did not use an interview schedule. Interviewees were asked to talk in detail about their experience and reflections on NHS quality‐monitoring (with an emphasis on CHI, CHAI and CQC) and standard‐setting (with an emphasis on NICE). Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained. Eight of the 11 interviewees consented to their responses being attributable to them. Our interviewees were also offered the opportunity to read and comment on their interview transcripts and a draft copy of this paper prior to its submission for publication.

Data analysis

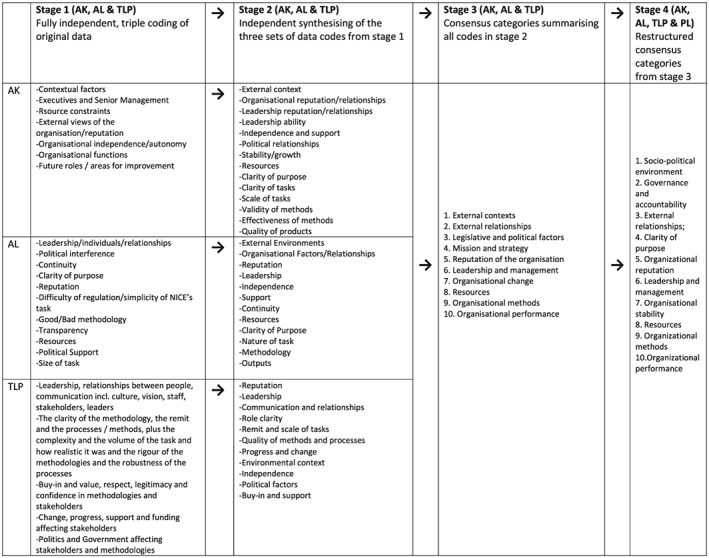

Three disinterested data judges (AK, AL and TLP) undertook conventional qualitative content analysis to identify patterns of responses (categories) within and across interviews. The data judges worked independently to minimize the influence of individual bias and to ensure that our analysis was rigorous and credible. The analysis comprised four main stages. First, independent coding schemes were developed by each data judge (Stage 1). This involved each judge working fully independently to develop his or her own summary of the interview data. The judges listened to all interview recordings and read each interview transcript repeatedly to become immersed in the data. The judges then made detailed notes on each interview. These notes were condensed and structured in an iterative process until each judge had developed his or her own summary (coding scheme) that was solely derived from the data. Judges then tested the coding schemes by checking them against the interview data to ensure that the categories and sub‐categories were appropriate, comprehensive and parsimonious.

Second, each coder took all of the three independent coding schemes, and independently created a new coding scheme that incorporated all of the insights from each coder (Stage 2). Third, the coders came together to discuss their coding schemes, and agreed on a single composite coding scheme that captured all of the insights from the individual coding schemes (Stage 3). After meeting to discuss similarities and discrepancies in categories and structure, one judge (AK) presented the composite coding scheme to the data auditor (PL). The auditor recommended alterations to the coding scheme after examining the categories and their definitions (Stage 4). The audited coding scheme was checked against the interview data independently by each of the judges, who met again to discuss whether the categories were appropriate, comprehensive and parsimonious. This process continued for six iterations until a final coding scheme was developed that was endorsed by each of the data judges and the auditor.

The three data judges independently applied the final coding scheme to the interview transcripts. Each judge coded every interview transcript independently using the final coding scheme. The judges then met to resolve discrepancies in their codings through discussion. The output of this stage was full coding of each interview transcript using the final coding scheme. Sections of interview transcripts were coded into multiple categories where necessary.

Principle agent modeling

The principal and agent theory emerged in the 1970s from the combined disciplines of economics and institutional theory. The theory has been extended well beyond economics or institutional studies to all contexts of information asymmetry, uncertainty and risk. The principal‐agent problem arises where the two parties have different interests and asymmetric information (the agent having more information), such that the principal cannot directly ensure that the agent is always acting in its (the principal's) best interests, particularly when activities that are useful to the principal are costly to the agent, and where elements of what the agent does are costly for the principal to observe. Moral hazard and conflict of interest may arise. Indeed, the principal may be sufficiently concerned at the possibility of being exploited by the agent that he chooses not to enter into a transaction at all, when that deal would have actually been in both parties' best interests: a suboptimal outcome that lowers welfare overall. The deviation from the principal's interest by the agent is called “agency costs”. Various mechanisms may be used to align the interests of the agent with those of the principal, including the threat of termination of employment.

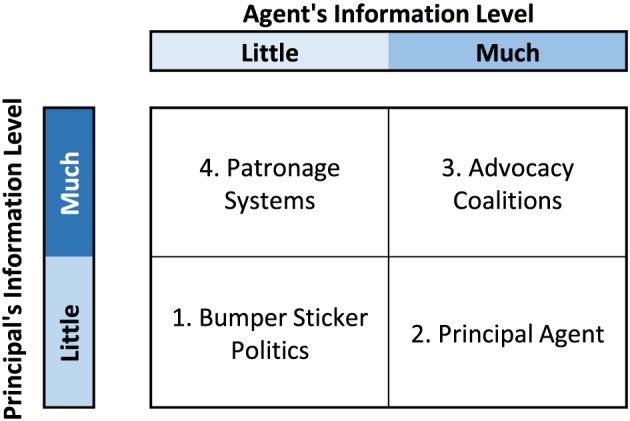

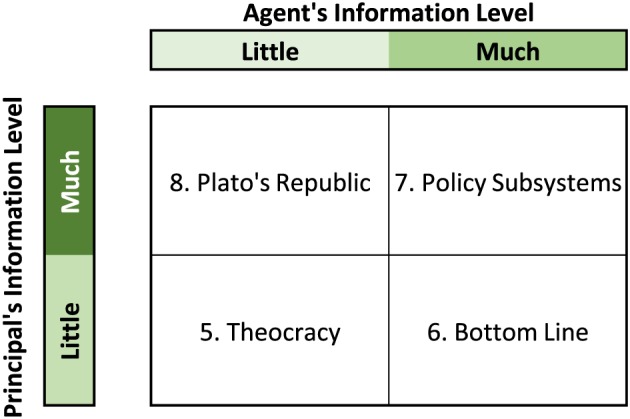

The Waterman and Meier approach challenges the assumption of normal principal‐agent modeling that goal conflicts and information asymmetry are constants. Using these as variables (instead of constants) creates eight states of principal agent interactions. A description of these states (as presented in Waterman and Meier's paper) and what they mean for the principal agent interactions is provided in Figures 1 and 2. In our study using the themes identified by the interviews it was possible to locate the organizations within the Waterman and Meier framework and track their changing position in the eight possible states over time.

Figure 1.

The Waterman and Meier expanded Principal‐Agent model (i) Goal Conflict. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 2.

The Waterman and Meier expanded Principal‐Agent model (ii) Goal Consensus. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Results

Interviews

Figure 3 presents the results of the initial two rounds of independent content analysis and then the two rounds of consensus content analysis. There was close concordance throughout all the stages.

Figure 3.

Flow diagram of the evolution of the themes from independent analyses to final consensus

Ten overarching themes were identified as influencing the functioning of the NHS regulatory institutions: Socio‐political environment; Governance and accountability; External relationships; Clarity of purpose; Organizational reputation; Leadership and management; Organizational stability; Resources; Organizational methods; Organizational performance. These are presented in the box together with a definition and a synthesis of the range and nature of our interviewees' responses relating to these themes, together with illustrative quotations.

Box. Themes created by content analysis of interviews and a description of their impact on the functioning of the quangoes together with illustrative quotations.

| Theme | Definition | Impact on NICE and CHI, Health Commission and CQC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Socio‐political environment | Outside conditions or situations that influence the performance of the organization (e.g. economic context, health sector context, inter‐organizational context, etc.) | The period of investigation can be divided into two phases. The first phase, 1999–2007 witnessed the greatest increase in spending in NHS history, resulting from the announcement by Tony Blair during a weekend television interview that the UK would aim to increase funding on healthcare until it matched the European average. This period was followed by the lowest growth in the NHS history as a result of public sector savings in response to the global financial crisis. In the first phase, NICE faced problems as it was rejecting drugs at a time of financial investment in the NHS. In the second phase, the introduction of austerity measures by the incoming coalition government had a direct effect on the establishment of the CQC. There were tight controls on appointment of new staff at a time when the CQC was expected to expand and take on extensive new responsibilities NICE was not the only NHS standard‐setter during this period. Initially, there were a range of organizations with overlapping responsibilities issuing guidance, setting standards and targets, including the National Patient Safety Agency, the Modernisation Agency, the National Service Frameworks (led by clinical leaders from within the Department of Health [DH]), as well as central NHS targets relating to waiting times, and the Quality Outcomes Framework for general practitioners. Except for those that remain directly managed by the DH and NHS England, the other organizations have now largely been disbanded as part of the “bonfire of the QANGOS” undertaken by successive administrations. 13 |

| 2. | Governance and accountability | The extent to which the organization is supported or hindered in its carrying out its mission and strategy by political agenda and legal frameworks | NICE and the monitoring bodies had very different relationships and understanding with the DH and Government on how they fitted into the NHS governance structures. Linda Patterson was clinical vice president of the Royal College of Physicians when interviewed, and was the medical director of CHI from its inception until its role was taken over by the Healthcare Commission. She had also been a member of the NICE appraisal committee. She described a relationship where both CHI and DH were unsure of what to expect from each other. While she believes that the CHI struggled initially to “get to the heart of what quality care was about”, she is also adamant that the organization was peopled by a highly committed team that had begun to make an impact and would have gone on to achieve significant results. Even when the government signalled its intention to incorporate an audit function into the remit of the CHI (previously the responsibility of NICE), turning CHI into the Health Commission, Linda and her colleagues fully expected to continue the work they had begun rather than having their contracts immediately terminated “I don't think the government understood that we really were independent. They thought they could ring us up and tell us what to do. There was also pressure for a quick fix. They thought we were taking too long. They wanted results. They became impatient, which was a real fault of the Labour government”……..“It [the new organization] was named deliberately to sound the same as before. We were told ‘there's going to be a change, it's a legislative change, we're going to have a slight change of name’. And we thought we were just carrying on. We were just completely chopped off, you know. We carried on working [until the last day]. We had this real commitment and we wanted to leave a legacy and we wrote quite a lot of legacy documents to say what would have been the learning out of this, that and the other. And we carried on delivering, as I say, I remember doing this big piece of work the day before I left”………[ A similar picture was presented by Peter Homa “There were some early skirmishes. I remember that one of the special advisers wrote an article that was designed to be published under the name of, I think it was Deidre Hine (Chairman of CHI), which was completely dissonant with either what we expected to do or how we expected to do it. And we refused to publish the thing, or refused to endorse it, which didn't go down very well at the time” …“Some of the less senior civil servants had absolutely no experience of what the NHS did in practice, let alone how you created an organization from scratch. And therefore we often had some quite tetchy exchanges with them…… And the extent to which they can understand what it is, not just CHI, but any other organization, is trying to do is very, very important as appears to be the case now in terms of the CQC, because the docking arrangements for the Department appear to be full‐on support as far as I can tell. So there were frissons between us and the Department of Health. The [CHI] commission and commissioners were very clear within CHI that we were independent. Obviously we tried to do our best to be helpful and supportive, but that didn't mean that would soften our reports. And there were a number of occasions when the NHS wanted us to soften our reports, and often some quite senior people in the Strategic Health Authorities and we were saying, ‘No, thank you very much. These are our findings, this is what we're saying’. Our primary obligation is to patients”. Obviously, we were concerned to make sure that we were fair and we gave a balanced account where that was appropriate”. A similar picture was presented by Sir Ian Kennedy who took over as chairman of the health commission. This level of reported conflict between the quality‐monitors and government is in stark contrast to the apparent relationship between the DH and NICE in its formative years “There was no attempt at all to interfere. Actually ministers realized the value of having us, as it were, as a fig leaf for them, the ‘blame quango’. They found that very useful. So it genuinely was independent” Sir Michael Rawlins. However, as current NICE chair David Haslam pointed out, it is perhaps difficult to judge whether NICE was left alone to do its job because it was performing effectively or if performed effectively because it was left alone to do its job. Either way, he said, the message is clear: “Leave things alone and they do better”. |

| 3. | External relationships | The nature and quality of relationships between the organization and its external stakeholders. | Engagement with key stakeholders was cited as an important factor in determining the path of NICE and the regulatory institutions. NICE garnered support from many of the royal medical colleges and from the BMA at an early stage. This included locating the National Collaborating Centres for the development of clinical guidelines within consortia of Royal Colleges, and commissioning university departments to produce appraisal reports through a contract with NHS R&D (which later became the National Institute for Health Research). These were both fully funded contractual arrangements. In contrast, members of NICE's extensive range of advisory committees were not reimbursed, although this never caused any difficulty in recruiting high quality professionals. However, NICE faced considerable resistance from the stakeholders—notably from the pharmaceutical industry and from patient groups—who objected to some of its decisions about specific drug treatments. In some cases the two joined forces, says Sir Michael Rawlins: “For a time, some pharmaceutical companies were winding up patient organizations and giving them pro bono PR help. When I discovered that I went very public about it and I castigated the patient organizations that were doing it”. In contrast, CHI found difficulty in gaining the enthusiasm of senior clinicians. Linda Patterson felt that the DH made insufficient effort to facilitate the involvement of senior clinicians and managers in CHI's inspection work. Subsequent monitoring organizations did not seek extensive senior involvement at a managerial level until 2013 when the prime minister announced the appointment of a Chief Inspector of Hospitals for CQC and later primary care and social care. |

| 4. | Clarity of purpose | The role of the organization as stated in establishment instruments including the Health and Social Care Act 2012, and how the organization goes about fulfilling that role. | Right from the start “NICE had a clear intellectual paradigm” says Albert Weale. The role of CHI was based on much more nebulous criteria, says former DH director of policy and planning Andy McKeon, who was instrumental in drawing up the 1997 white paper: “what ministers wanted was a policeman; what they got was a social worker”. That uncertainty appears to have dogged CHI and its successors ever since. This may be expected, as the day‐to‐day monitoring of quality in the whole of the NHS is a magnitude larger and more complex than technology assessment and guidance development. A number of interviewees considered the model that the centre was seeking to develop was an external regulator to monitor the quality of a whole range of public and private providers required in a mixed health economy, in what Rudolf Klein called a “mimic market” 14 |

| 5. | Organizational reputation | The overall estimation in which an organization is held by its internal and external stakeholders based on its past actions and probability of its future behaviour. | The constant restructuring, new leaders and novel methodologies meant that no single monitoring organization ever had sufficient time to establish a reputation. In contrast, NICE confirmed its presence as a “significant player” with its first controversial decision not to approve Relenza being reached in October 1999, only 7 months after the Institute was established. Paradoxically, NICE has not yet established its appraisal processes so this decision was made by an ad hoc process consisting of Andrew Dillon, Peter Littlejohns, Ray Tallis and Jo Collier. While early comments from the Royal Colleges were wary about the Institute they soon became strong advocates of NICE and, through the creation of the national Collaborating Centres, became the major source of NICE clinical guidelines. |

| 6. | Leadership and management | Leadership is the ability of senior managers to influence other people to guide, structure and facilitate activities and relationships. Management is the ability of senior managers to ensure that leadership goals are achieved via supporting, monitoring, directing and motivating performance. | The constant changing of the quality‐monitoring organization meant that there was a complete change in senior staff approximately every 5 years. Despite the high quality of the staff, each new organization adopted a different methodology and staff were chosen accordingly. The first approach was as a “supporting” organization, headed by a senior health manager and senior clinical staff. The second approach was based on monitoring data and it was considered necessary to have NHS managers or clinicians as advisors rather than in senior management roles. The third approach was based on registration and re‐introduced inspections while adopting a management model with health managers in senior posts with professional advisors at national local levels. After the CQC changed its method of inspections in 2013, senior clinical professionals again took centre stage (i.e. chief inspectors for hospital, primary care and social care). In contrast, the NICE senior team was remarkably constant |

| 7. | Organizational stability | Fundamental internal or external alterations to the organization or its role. | The most commonly cited cause for the deleterious effects on quality monitoring was organizational change. The quality‐monitoring quangos went though many politically initiated organizational changes that impacted on the way it delivered its function. The inherent difficulty of quality improvement and its monitoring is compounded by the fact that, no matter how good a health care system is, high‐profile disasters will inevitably occur. When they occur they create tremendous political pressure to change the leadership and procedures of whatever institution is involved in the process. NICE also had many changes to its role and functions (changing its name 3 times) but was able to adapt and respond to its new responsibilities. However, NICE did not take on all potential new functions. For example, discussions on patient safety continued until the National Patient Safety Agency was closed down and the function absorbed by NHS England. Furthermore, despite many discussions with the DH on the UK screening programme and the immunization and vaccination programmes, these programmes remained within the DH. A strong feature was that NICE had developed a generic way of working, and a set of principles and mode of working that could be applied (in various forms) to all new commissions. |

| 8. | Resources | Stocks or reserves of money, materials, people or other assets, which can be drawn on by the organization when required. | NICE presented a very clear message to the DH that any new work required new funding, and a realistic business case was always prepared. The changing nature of the quality‐monitoring organization (which always involved merging of a range of existing organizations) meant that this was always going to be very difficult. The climax of the resourcing crisis came when the new CQC was given a hugely expanded registration brief, at the same time as new appointments were frozen in the wake of austerity measures “At that stage CQC was effectively given a virtually impossible job. It was asked to merge three organizations of very different backgrounds and traditions, very different cultures and very different ways of working, into one. That's difficult enough. But it was also asked to take on a whole new way of regulation and register providers in one fell swoop. At the same as the money started getting very, very tight. And so, not only did that mean that the money was getting tight, but people's expectations of what you would do with the money were going higher. All of that was kind of happening at the time that CQC was being asked to do an impossible job”. Andrea Sutcliffe. |

| 9. | Organizational methods | The reliability, validity and comprehensiveness of the processes that are used by the organization to generate its products or outputs. | Methods probably reflect the biggest differences between the two functions. NICE in its appraisal and guideline programmes was building on international consensus on technical methods, and an evidence base and robust processes on which to deliver them. In addition, NICE harnessed the expertise of the NHS, the Royal Colleges and the University sector. NICE sought not to produce guidance itself, but to design and quality‐assure processes where independent advisory bodies developed the guidance. NICE took responsibility to issue the final recommendations to protect their advisors from incrimination from disgruntled stakeholders. The monitoring organizations adopted differing approaches reflecting a lack of consensus on how quality should be assessed and regulated. “…..the task we had was really both important but very tough, not least because we were serving two countries, England and Wales. And we had to invent [the methods], it was a bit like building a plane whilst flying it, because we had to assemble, at very short, within a very short period of time, the inspection methodology. And then we had, under very considerable pressure from the Department of Health, to deliver comprehensive coverage of the inspections across the NHS, and we were always very exercised about making sure we didn't proceed so fast we made errors, and say something was safe when it wasn't” Peter Homa. |

| 10 | Organizational performance | The quality of an organization's products and outputs, and stakeholders' satisfaction with those products or outputs. | Despite controversial decisions, NICE's outputs and processes became highly regarded, often more overseas than in the UK. This was useful to maintain government support, as ministers were constantly being reminded by other countries of the value of NICE. NICE remained thick‐skinned to domestic criticisms, and was willing to explain its decisions. It always fielded speakers at conferences to which it was invited, and on radio and TV programmes exploring its decisions. This allowed a build‐up of rapport with the media that allowed complex issues to be explored. In contrast, the quality‐monitoring organizations had difficulty in achieving this continuity and, paradoxically, in the end was often more criticized than the failing hospital on which it was reporting. |

Locating institutions in principle agent model

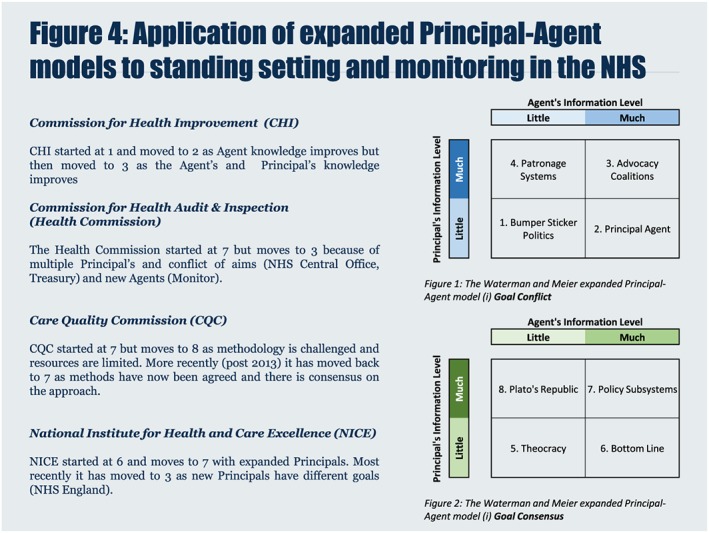

Our interview study identified that goal conflict as described in the “clarity of purpose” theme, and information asymmetry (guidance development and regulatory methodology) as presented in the“ organizational methods” theme were key features that dominated the nature of the relationship between the principal and agent (see box and sections on clarity of purpose and organizational methods). The relationships between the principals and the agents were not static and each organization could be tracked according to the eight states over time reflecting the various permutations of goal conflict and information asymmetry (Figure 4). Furthermore the other themes derived from the interviews help explain why the organization could be located in the which particular state. CHI started with an obvious goal conflict with the DH (see box and clarity of purpose theme) and as neither the agent nor principal had a clear understanding of the appropriate method of monitoring quality (as determined by the interview responses) it started in state 1. It moved to state 2 as CHI became clearer on the methodology it wished to use (see comments of Peter Homa in organizational methods in box) but then moved to state 3 as the DH increased its understanding of what it required. The differing views on the appropriate method of regulation increased the goal conflict and became so dominant that the principle DH created a new agent rather than continue to negotiate with CHI and it was closed down. The Health Commission started at state 7 as there was a clear (but perhaps only perceived) consensus on the goal and on methods of regulation. However it moved to state 3 as the consensus was lost or it was realized had never existed. The interviews suggest that this was also a function of other existing principals other than the DH exerting influence and new principals being created. It was reported that senior NHS management considered that the Health Commission reports were unduly negative and damaging to the reputation of the NHS. The involvement of new principals entering the regulatory arena brought their own set of goals. The key new principal was Monitor established by the Treasury in order to take on responsibility for monitoring the financial viability of the emerging new NHS structures. This led to confusion in the regulatory landscape and again resolution did not happen and the Health Commission was dissolved. A third quango CQC was established. CQC started at state 7 as there was goal consensus and both agent and principle had good knowledge of what information and methods were required. But its position moved to state 8 as CQC's methodology was challenged based on the publication of a series of independent reports highlighting the poor quality of care in some NHS institutions that the CQC had considered were providing good care according to their methods. Their ability to respond to this criticism was severely hampered as resources were not available because of the new period of austerity (see Andrea Sutcliffe's comments in box, resources theme). More recently, post 2013, after the senior management team had been replaced and new methods introduced (based on multi‐professional inspection teams) CQC has moved back to state 7. However this situation remains precarious as its methods are resource intensive and may not be sustainable in the long term. NICE started at state 6 as it had a monopoly on the knowledge of methods for health technology assessment and guideline development and consensus with the DH on its main goal which was to assess value for money. It remained there for some time until new principals emerged, e.g. NHS England. Its position then switched to state7 as the new principal NHS England considered that they were as knowledgeable regarding methods. An example of this is when NHS England produced guidance previously developed by NICE and in essence took on an “agent” function. However there are also examples of classical policy subsystems existing, e.g. the joint working between NICE and NHS England on the creation of the new Cancer Drugs Fund (Littlejohns et al., 2016). However as new goals for controlling NHS total cost (as opposed to assessing cost‐effectiveness) became important and the financial crisis deepened goal conflict emerged and NICE's position moved to state 3. So over time while starting from different positions, 3 quangos eventually ended up in state 3. Two just before they were closed down and NICE is currently at 3.

Figure 4.

Application of expanded Principal‐Agent models to standing‐setting and monitoring in the NHS. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Discussion

Making sense of health policy decisions and assessing their impact on the quality of health care are notoriously difficult. Our results suggest a series of interrelated factors affected the functioning of standard‐setting and the quality‐monitoring organizations. Our interviewees described different patterns of characteristics and internal/external relationships between NICE, the quality‐monitoring organizations, and the NHS and the Department of Health, which they believed were directly associated with the functioning and success of the organizations. None of these will be a surprise to those working in the field, but two features stand out. The first feature is political influence. It is inevitable with a national health system directly funded through taxation, and which is at the heart of the politics of a country, that politicians will want significant control. This can lead to goal conflict. Our findings suggest that this had a profound effect on the ability of the NHS to monitor the quality it is providing. The second feature is that clear methodology based on best evidence (both technical and organizational) led by stable professional leadership (clinical and managerial) can help NHS institutions to deliver on their remits, or at least extend their time of functioning, even within a fickle and changing political environment. It is not possible to be absolutely certain how these themes link together, although it is plausible to postulate that one summation could be that differing policy objectives between the Department of Health and other government agencies and those responsible for monitoring NHS quality (Theme 2 and 4) resulted in central involvement and organizational change (Theme 7). This had a disruptive effect on the ability of the NHS to monitor quality. However constant professional leadership, both clinical and managerial (Theme 6) and basing decisions on best evidence, both technical and organizational (Theme 9) helped the function to be delivered, even within a changing political/policy environment (Theme 1).

Application of the Waterman Meier framework enabled an understanding and description of the dynamic relationship between central government and quangos in the NHS and may predict when tensions will arise in the future. The study data collection finished in 2013 but it is still possible to track the institutions. The development of the cancer drugs fund represented a definite goal conflict between the DH and NICE (Littlejohns 2016). Furthermore the establishment of NHS England and Public Heath England represents the entry of new principles in the health landscape and examples of how this relationship is likely to develop can be demonstrated by a range of new decisions, e.g. the termination of the “staffing guidance” that was originally commissioned from NICE by NHS England (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2015). This reflects a new goal conflict as cost savings dominate the NHS England agenda rather than cost‐effective guidance based on best evidence. On the other hand the continuing debate between the government and junior doctors over pay and work patterns shows what can happen when no recognized intermediary quango exists and the challenge of having no agent in place.

NICE and the quality‐monitoring organizations have received much media coverage since 1999. However, media coverage has often been distorted by limited access to a wide sample of senior managerial voices, political or journalistic biases, and a restricted or short‐term outlook. This is the first scientific study to capture insights on standard‐setting and quality‐monitoring in the NHS though the experiences of key players at the institutions established to deliver them. We have attempted to analyze our interview data systematically and in an unbiased way and apply a political paradigm. A key strength of the study was the candidness and honesty of the interviewees, who clearly welcomed the opportunity to be involved in this study and to have their position represented in an academic report. A potential limitation of the study is that we did not sample every individual in a senior management position in quality‐monitoring and standard‐setting organizations. By asking those directly involved, we will obviously only get part of the picture, but is a legitimate approach to narrative research (Greenhalgh et al., 2005). Indeed, there are probably as many takes on the “truth of the matter” as there are key players, and yet common themes did emerge from the data. We mitigated the potential criticism of researcher reflexivity in two ways. First we employed an independent journalist to conduct unstructured interviews with no pre‐determined questions or interview schedule. Second, we ensured that PL's past experience working at NICE did not contaminate our data analysis by employing three disinterested data judges to conduct the analysis. In these ways we ensured that the results could not be a simple reflection of the questions that were asked, or the research team's prior knowledge or experience.

While the Lansley reforms were supposed to distance politicians from the day to day functioning of the NHS, recent developments around staffing and 7 day working have returned politics right at the heart of health care provision. Having a framework with which to explore this relationship in a robust and dispassionate way will be useful. We have shown that principle agent modeling describes and may predict how future relationships occur between key players and could be useful in minimizing some of the damaging extreme positions that can be taken.

While our study was undertaken in England, the findings may be of interest to other countries seeking to improve quality of care through central directives.

Acknowledgements

We thank the interviewees for participating in the research. We would also like to thank Professor Steven Pearson and Professor Rudolph Klein for commenting on early drafts of the paper.

PL, AK and KK are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London at King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

AK was supported initially by Guy's and St Thomas' Charity.

Peter Littlejohns was the founding Clinical and Public Health Director of the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) from 1999–2011. In this role he designed the process and methods for the development of NICE guidelines and was the Executive Director responsible for the Citizens Council and the R&D programme.

Littlejohns, P. , Knight, A. , Littlejohns, A. , Poole, T.‐L. , and Kieslich, K. (2017) Setting standards and monitoring quality in the NHS 1999–2013: a classic case of goal conflict. Int J Health Plann Mgmt, 32: e185–e205. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2365.

References

- BBC News . Stafford Hospital: ‘I am truly sorry’—David Cameron. Secondary Stafford Hospital: ‘I am truly sorry’—David Cameron 2013, 6 February. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk‐politics‐21348901.

- Campbell D. J. Hunt: NHS ‘mediocrity’ could create another Mid Staffs scandal. Secondary Jeremy Hunt: NHS ‘mediocrity’ could create another Mid Staffs scandal 2013, 8 March. http://www.theguardian.com/society/2013/mar/08/jeremy‐hunt‐nhs‐mediocrity‐mid‐staffs.

- Chief Inspector Steve Field has ‘lost confidence of GPs’ and is ‘no longer viewed as fair and impartial’. Publication date: 17 December 2015. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/news/2015/december/cqc‐chief‐inspector‐steve‐field‐has‐lost‐confidence‐of‐gps.asp

- Department of Health . The New NHS. Secondary The New NHS 1997. http://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the‐new‐nhs.

- Francis R. 2012. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. The Stationery Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Russell J, Swinglehurst D. 2005. Narrative methods in quality improvement research. Qual Saf Health Care 14: 443–449. DOI:10.1136/qshc.2005.014712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) Act 2003 . Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/43/contents (Accessed: 1 June 2016).

- The Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Commencement No.9, Consequential Amendments and Transitory, Transitional and Saving Provisions) Order 2009, SI 2009/462 . Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2009/462/schedule/4/made (Accessed: 1 June 2016).

- Horton R. 1999. NICE: a step forward in the quality of NHS care. The Lancet 353(9158): 1028–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. 2005. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15(9): 1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R. 2010. The New Politics of the NHS: From Creation to Reinvention, 6th edn. Radcliffe Publishing Ltd: Milton Keynes. [Google Scholar]

- Lancet . 2013. Thank you Michael, welcome David: a new era for NICE. The Lancet 381(9863: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R, Alvarezrosete A, May A. 2006. How to Regulate Health Care in England. Kings Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Littlejohns P, Kelly M. 2005. The changing face of NICE: the same but different. The Lancet 366(9488): 791–9418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlejohns P, Weale A, Kieslich K, et al. 2016. Challenges for the cancer drugs fund. Lancet Oncol 17(4): p416–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris K. 2009. Michael Rawlins: doing the NICE thing. The Lancet 373(9672): 1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . NHS England asks NICE to suspend safe staffing programme. Secondary NHS England asks NICE to suspend safe staffing programme 2015. http://www.nice.org.uk/news/article/nhs‐england‐asks‐nice‐to‐suspend‐safe‐staffing‐programme

- Public Accounts committee report into the CQC . 2015. http://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees‐a‐z/commons‐select/public‐accounts‐committee/inquiries/parliament‐2015/care‐quality‐commission‐15‐16/

- Waterman RW, Meier J. 1998. Principal‐Agent Models: an expansion. J Public Admin Res Theory J‐PART 8 2: 173–202. [Google Scholar]