Despite increased attention being paid to stillbirth‐related issues in recent years, problems with definitions and procedures associated with stillbirth registration continue to plague public health surveillance and clinical care.1 Issues that need to be addressed include the distinction between fetal death and stillbirth, the lack of standardised viability criteria for stillbirth registration and reporting, the inclusion of medically or surgically terminated pregnancies (therapeutic abortions) in the stillbirth counts of some countries, and contemporary stillbirth‐related administrative processes that may adversely affect clinical care. This paper presents the deliberations of a Consensus Conference held in Vancouver, Canada on 9 October 2015, with the goal of improving fetal death registration procedures. The issues discussed are of particular relevance to high‐income countries, although the proposed rationalisation and standardisation of definitions and procedures is applicable everywhere.

In 1950, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined fetal death as ‘death prior to the complete expulsion or extraction from its mother of a product of conception, irrespective of the duration of pregnancy; the death is indicated by the fact that after such separation the fetus does not breathe or show any other evidence of life, such as beating of the heart, pulsation of the umbilical cord or definite movement of voluntary muscles’.2 This definition does not specify viability criteria, such as a specific birthweight or gestational age, to distinguish between spontaneous pregnancy losses (miscarriages) and stillbirths, nor does it exclude fetal deaths due to therapeutic abortion. Many countries use this definition of fetal death, although some (e.g. Italy, Sweden and the USA) have modified this definition to specifically exclude fetal deaths that follow therapeutic abortion.

Whereas the WHO definition of fetal death effectively conflates fetal death and subsequent (still)birth, ultrasound imaging and other developments have provided clarity regarding the timing of these two events. Fetal death can precede the birth of the dead fetus (i.e. stillbirth) by days or weeks, with the duration of the interval sometimes dependent on patient and physician choices and the availability of labour induction. Both fetal death and stillbirth are meaningful events for the mother and family, although their prognostic significance and requirement for health services vary.1

The WHO recommends that national reporting of fetal death be restricted to fetal deaths with a birthweight ≥500 g.2 If birthweight is unavailable, then the WHO recommends the use of a ≥22‐weeks of gestation criterion, and if that information is also missing, a crown–heel length of ≥25 cm. Such sequential use of applicable criteria differs significantly from the use of dual criteria currently extant in many countries.1 For instance, countries such as Finland and Iceland require the registration of stillbirths with a gestational age ≥22 weeks or a birthweight ≥500 g. Use of dual criteria is conceptually flawed and lacks coherence; in the instance above, stillbirths are restricted to those ≥22 weeks under the gestational age criterion, whereas the birthweight criterion (≥500 g) permits the inclusion of variable proportions of stillbirths between 20 and 24 weeks (see Table S1).3, 4, 5, 6 A strong case can therefore be made for a single viability criterion and recent progress in gestational age ascertainment supports the use of gestational age alone for determining viability e.g. ≥20 weeks of gestation (given steadily decreasing viability limits), with birthweight ≥400 g to be used if gestational age information is not available.

There is substantial international variability in stillbirth registration criteria.7, 8 For instance, Norway registers stillbirths ≥12 weeks of gestation, the Netherlands and the UK register stillbirths ≥24 weeks of gestation, whereas Italy requires registration at ≥180 days of gestation.1 In the USA, a few states register all products of conception, another 25 states register stillbirths ≥20 weeks of gestation, and 12 states register stillbirths ≥20 weeks or ≥350 g.1 Varying criteria for registration and variability in adherence with these criteria seriously limits the value of international comparisons of stillbirth rates. A study ranking 28 high‐income countries based on crude stillbirth rates resulted in Sweden receiving a rank of third, whereas the United States (ranked 23rd), Canada (27th), and Australia (28th) performed less well.7 However, ranks recalculated after restricting stillbirths to those ≥1000 g birthweight (i.e. after excluding stillbirths likely to be affected by differences in registration criteria) substantially changed the rankings. Sweden dropped to 10th rank, whereas Australia, Canada and the USA improved to 11th, 12th and 17th, respectively.7

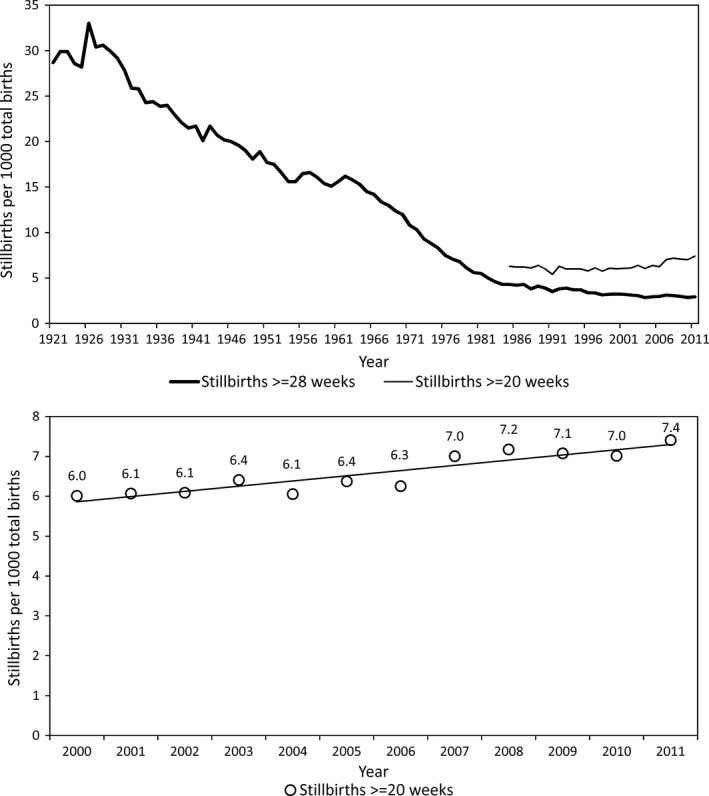

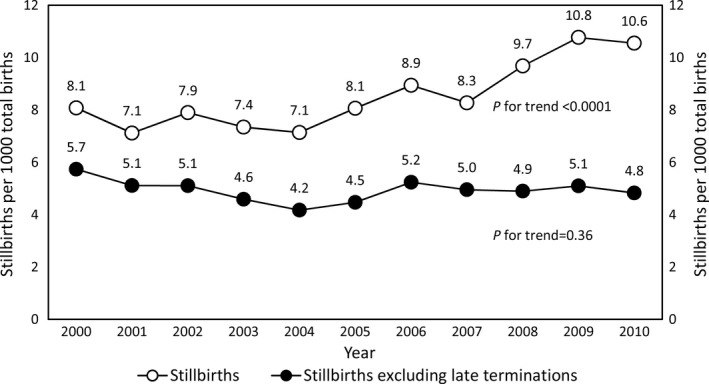

Artefactual differences in international stillbirth rates are also caused by a lack of standardisation regarding the need to register medically terminated pregnancies as stillbirths. Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the Netherlands and the UK count medically terminated pregnancies as stillbirths if they satisfy the requisite birthweight or gestational age registration criteria, whereas Denmark, Finland, Italy, Norway, Sweden and the USA do not.1 The magnitude of the difference caused by this variance in registration requirements depends on the viability criteria for stillbirth registration. Australia, Canada and New Zealand, which include therapeutic abortions in stillbirth counts and register stillbirths ≥20 weeks of gestation, are at a greater disadvantage than the Netherlands and the UK, which also include pregnancy terminations in stillbirth counts but only register stillbirths ≥24 weeks of gestation.1 In Canada, recent increases in prenatal diagnosis and pregnancy termination for serious congenital anomalies have resulted in a corresponding temporal increase in stillbirth rates (Figures 1 and 2).9 Australia and New Zealand have also witnessed periodic temporal increases in stillbirth rates in recent years.10, 11, 12 .

Figure 1.

Rates of stillbirth ≥28 weeks of gestation, Canada 1921–2011 and rates of stillbirth ≥20 weeks of gestation, Canada 1985–2011 (upper panel) and rates of stillbirth ≥20 weeks of gestation, Canada, 2000–2011 (lower panel).

Figure 2.

Overall stillbirth rates and stillbirth rates excluding late pregnancy terminations (therapeutic abortions), British Columbia, Canada, 2000–2010.9

The inclusion of medically terminated pregnancies in stillbirth counts can defeat the purpose of fetal death surveillance, as therapeutic abortions and spontaneous fetal deaths are aetiologically and otherwise distinct. Medical terminations of pregnancy need to be disaggregated from spontaneously occurring fetal deaths. Such a mechanism does not currently exist in countries such as Canada and, not surprisingly, the recent temporal increase in stillbirths in Canada (Figure 1) was initially attributed to increases in older maternal age, maternal chronic disease and other factors, instead of pregnancy termination.9

Stillbirth registration procedures, modelled after live birth registration and not death registration, can impact patient care because they mandate parental involvement. In most jurisdictions, the law requires that parents complete stillbirth registration forms and submit the completed forms to the Vital Statistics Office (which, in addition, receives a separate physician/midwife notification of stillbirth). The legal formalities associated with stillbirth, which require the mother to be directly involved in completing the stillbirth registration documents and in the burial/cremation arrangements, may add to the psychological trauma experienced by some grieving mothers. Such problems are best illustrated by women undergoing a fetal reduction procedure for multi‐fetal pregnancy. Women with triplet pregnancies who undergo fetal reduction at 10 weeks of gestation and deliver twins at term in Canada are required to complete stillbirth registration forms and arrange for the burial/cremation of the reduced fetus. The need to revisit their decision to terminate a healthy fetus months after the event and at the time of birth of the twin siblings can be traumatic and some women are unable to complete the required paperwork. This leaves the Office of Vital Statistics with incomplete paperwork, while the reduced fetus is left in the morgue as abandoned remains. Similar problems are sometimes faced by women who undergo medical termination of pregnancy following prenatal diagnosis of a serious congenital anomaly. The elective nature of the procedure, and psychological support notwithstanding, some women are distraught in the immediate postpartum period and may leave hospital without completing the stillbirth registration forms and without making arrangements for the burial/cremation of fetal remains. Nursing staff facing deadlines for submitting patient‐completed stillbirth registration forms to the Office of Vital Statistics, find themselves in a quandary, as their repeated telephone calls appear to harass, rather than help, the grieving mother. Unfortunately, stillbirth registration and burial requirements are legislated necessities (albeit based on outdated laws) and cannot be altered by hospital authorities.

The foregoing arguments and evidence imply the following new definitions for fetal death and spontaneous fetal death. Fetal death is defined as death before the complete expulsion or extraction from its mother of a product of conception, irrespective of the duration of pregnancy; the death is indicated by the fact that before such separation the fetus does not show any evidence of life such as beating of the heart on ultrasonographic examination. The time of fetal death is ideally ascertained by ultrasonographic means but may have to be based on the time of stillbirth in cases without ultrasonographic confirmation of death in utero. Spontaneous fetal death is defined as a fetal death that is not a consequence of a medically terminated pregnancy.

Consensus among Conference participants was achieved for the following recommendations:

-

1Documentation of fetal death registration should be revised as follows:

- Gestational age at fetal death should be recorded, in addition to the gestational age at stillbirth (i.e. the gestational age when the dead fetus was born).

- Gestational age at fetal death should be based on the healthcare provider's best estimate of when fetal death occurred. This estimate may be based on ultrasonographic imaging (e.g. through determination of the size of the expired fetus) or clinical examination (of the dead/macerated fetus).

- If the gestational age at fetal death is unknown, the gestational age at stillbirth should be recorded as the gestational age at fetal death.

-

2Criteria for registration of spontaneous fetal deaths should be revised as follows:

- Registration of spontaneous fetal deaths should be required for all fetal deaths occurring at ≥20 completed weeks of gestation.

- If gestational age at fetal death and gestational age at stillbirth are both unknown, a birthweight criterion of ≥400 g should be used to determine if the fetal death requires registration.

-

3

The process for the registration and reporting of therapeutic abortions should be separate from that for spontaneous fetal deaths.

The following recommendation was also discussed by Conference participants.

-

4Flexible administrative processes should be developed to respond to each woman's unique needs, so as to:

- Ensure that women are aware of, and supported in, opportunities to engage with decision‐making and procedures related to burial or cremation.

- Support and respect women's choices to participate or not participate in paperwork and other bureaucratic requirements through alternate mechanisms (e.g. by permitting healtcare personnel to complete forms and make burial/cremation arrangements).

No consensus was reached on this fourth recommendation. The absence at the Conference of women who had experienced a medical termination of pregnancy was voiced as a particular concern.

It is anticipated that a wider dialogue regarding these issues and recommendations will lead to an international consensus that will better align fetal death definitions and fetal death registration criteria and procedures with contemporary issues in obstetrics and maternity care. Concerned stakeholders should raise this agenda at appropriate venues so that legislation can be proposed and passed to modify the existing laws concerning fetal deaths and stillbirths.

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests available to view online as supporting information.

Contribution to authorship

The Consensus Conference was organised by KSJ, MB, CD, and LL. KSJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript based on the deliberations at the Conference and the manuscript was revised for intellectual content by MB, CD, LL, DE, DBF, DF, BK, MSK, KL, PS, DS, AS, AS, KW. All authors approved the final version.

Details of ethics approval

Not applicable.

Funding

See Acknowledgements section.

Consensus Conference Participants

Jaime Ascher1, Still Life Canada, Vancouver, Canada.

Melanie Basso, RN, MSN, Children's and Women's Hospital and Health Centre of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Cheryl Davies, RN, MEd, Children's and Women's Hospital and Health Centre of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Paromita Deb‐Rinker, PhD, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Canada.

Mary Lou Decou, PhD, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Canada.

Susie Dzakpasu, PhD, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Canada.

David Ellwood, DPhil, MB Bchir, Gold Coast University Hospital and Griffith University, Queensland, Australia.

Lynn Farrales1, MD, Still Life Canada and the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Deshayne Fell, MSc, BORN Ontario, Ottawa, Canada.

Dawn Fowler, MSc, National Abortion Federation, Victoria, Canada.

K.S. Joseph, MD, PhD, University of British Columbia and the Children's and Women's Hospital and Health Centre of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Brooke Kinniburgh, MPH, Perinatal Services BC, Vancouver, Canada.

Michael Kramer, MD, McGill University, Montreal, Canada.

Lily Lee, RN, MSN, Perinatal Services BC, Vancouver, Canada.

Ken Lim, MD, University of British Columbia and the Children's and Women's Hospital and Health Centre of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Wei Luo, MSc, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Canada.

Petra Selke, MD, University of British Columbia and the Children's and Women's Hospital and Health Centre of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Anne Sneddon, MB BS, Gold Coast University Hospital and Griffith University, Queensland, Australia.

Ann Sprague, PhD, BORN Ontario, Ottawa, Canada.

Wanda Vincent, British Columbia Vital Statistics Agency, Victoria, Canada.

Kim Williams, RN, MSN, Perinatal Services BC, Vancouver, Canada.

Supporting information

Table S1. Centiles of birthweight for gestational age at 20–22 weeks of gestation according to different fetal growth references

Acknowledgements

The Consensus Conference on definitions, registration issues and procedures related to fetal death and stillbirth was organised by the B.C. Women's Hospital and Health Centre and Perinatal Services BC. K.S. Joseph's work is supported by the Investigator Grant Award Programme of the Child and Family Research Institute and a Chair award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Funding for Open Access publication was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (APR‐126338).

Joseph KS, Basso M, Davies C, Lee L, Ellwood D, Fell DB, Fowler D, Kinniburgh B, Kramer MS, Lim K, Selke P, Shaw D, Sneddon A, Sprague A, Williams K. Rationale and recommendations for improving definitions, registration requirements and procedures related to fetal death and stillbirth. BJOG 2017; 124:1153–1157.

Linked article This article is commented on by S Alexander and J Zeitlin, p. 1158 in this issue. To view this mini commentary visit https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14381.

Note

Jaime Ascher and Lynn Farrales have, upon further reflection, expressed concerns about recommendation 3. Their concerns are related to a lack of adequate (community) participation at the Consensus Conference by women/families whose babies were stillborn (whether spontaneously or following pregnancy termination).

References

- 1. Joseph KS, Kinniburgh B, Hutcheon JA, Mehrabadi A, Dahlgren L, Basso M, et al. Rationalizing definitions and procedures for optimizing clinical care and public health in fetal death and stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:784–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . International Statistical Classification of Diseases, and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD‐10), 2nd edn Vol. 2 Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Williams RL, Creasy RK, Cunningham GC, Hawes WE, Norris FD, Tashiro M. Fetal growth and perinatal viability in California. Obstet Gynecol 1982;59:624–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alexander G, Himes J, Kaufman R, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol 1996;87:163–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, Joseph KS, Allen A, Abrahamowicz M, et al. A new and improved population based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age. Pediatrics 2001;108:E35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dobbins TA, Sullivan EA, Roberts CL, Simpson JM. Australian national birthweight percentiles by sex and gestational age, 1998–2007. Med J Aust 2012;197:291–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Joseph KS, Liu S, Rouleau J, Lisonkova S, Hutcheon JA, Sauve R, et al. Influence of definition based versus pragmatic birth registration on international comparisons of perinatal and infant mortality: population based retrospective study. BMJ 2012;344:e746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deb‐Rinker P, León JA, Gilbert NL, Rouleau J, Andersen AM, Bjarnadóttir RI, et al. Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System Public Health Agency of Canada. Differences in perinatal and infant mortality in high‐income countries: artifacts of birth registration or evidence of true differences? BMC Pediatr 2015;15:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Joseph KS, Kinniburgh B, Hutcheon JA, Mehrabadi A, Basso M, Davies C, et al. Determinants of increases in stillbirth rates from 2000 to 2010. CMAJ 2013;185:E345–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li Z, Zeki R, Hilder L, Sullivan EA. Australia's Mothers and Babies 2010. Perinatal Statistics Series No. 27. Cat. No. PER 57. Canberra, Australia: AIHW National Perinatal Epidemiology and Statistics Unit; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Australia's Mothers and Babies 2013—in Brief. Perinatal Statistics Series No. 31. Cat No. PER 72. Canberra: AIHW; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Health Quality and Safety Commission . Fifth Annual Report of the Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee: Reporting Mortality 2009. Wellington, New Zealand: Health Quality and Safety Commission; 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Centiles of birthweight for gestational age at 20–22 weeks of gestation according to different fetal growth references