Abstract

Objectives

To describe the characteristics, management and outcomes of women giving birth at advanced maternal age (≥48 years).

Design

Population‐based cohort study using the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS).

Setting

All UK hospitals with obstetrician‐led maternity units.

Population

Women delivering at advanced maternal age (≥48 years) in the UK between July 2013 and June 2014 (n = 233) and 454 comparison women.

Methods

Cohort and comparison group identification through the UKOSS monthly mailing.

Main outcome measures

Pregnancy complications.

Results

Older women were more likely than comparison women to be overweight (33% versus 23%, P = 0.0011) or obese (23% versus 19%, P = 0.0318), nulliparous (53% versus 44%, P = 0.0299), have pre‐existing medical conditions (44% versus 28%, P < 0.0001), a multiple pregnancy (18% versus 2%, P < 0.0001), and conceived following assisted conception (78% versus 4%, P < 0.0001). Older women appeared more likely than comparison women to have pregnancy complications including gestational hypertensive disorders, gestational diabetes, postpartum haemorrhage, caesarean delivery, iatrogenic and spontaneous preterm delivery on univariable analysis and after adjustment for demographic and medical factors. However, adjustment for multiple pregnancy or use of assisted conception attenuated most effects, with significant associations remaining only with gestational diabetes (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 4.81, 95% CI 1.93–12.00), caesarean delivery (aOR 2.78, 95% CI 1.44–5.37) and admission to an intensive care unit (aOR 33.53, 95% CI 2.73–412.24).

Conclusions

Women giving birth at advanced maternal age have higher risks of a range of pregnancy complications. Many of the increased risks appear to be explained by multiple pregnancy or use of assisted conception.

Tweetable abstract

The pregnancy complications in women giving birth aged 48 or over are mostly explained by multiple pregnancy.

Keywords: Advanced maternal age, assisted reproduction, cohort study, pregnancy, pregnancy outcomes

Tweetable abstract

The pregnancy complications in women giving birth aged 48 or over are mostly explained by multiple pregnancy.

Introduction

Childbearing at advanced maternal age is becoming increasingly common in high‐income countries.1, 2 Furthermore, developments in artificial reproductive technologies, such as ovum donation, may contribute to an increasing incidence of pregnancies in women outside the usual biological reproductive age. In England and Wales the average age at childbearing has increased steadily since the mid‐1970s from 26.4 in 1975 to 30.0 in 2013, with a corresponding rise in the proportion of women delivering in their thirties and forties.3

Many studies have reported an association between advanced maternal age and a higher risk of adverse maternal and infant outcomes.4, 5, 6 However, the majority of studies have reported outcomes in women aged ≥35 years or women aged ≥40 years. These studies therefore include only a small number of the oldest mothers and have not specifically assessed the risks in women of very advanced maternal age, in whom adverse outcomes could be more common. The small numbers of studies that have specifically investigated outcomes in relation to very advanced maternal age7 have largely not made any attempt to control for potential confounding factors and have predominately been conducted using retrospective review of medical records over a number of years in a single or small number of institutions. Such studies suffer from a number of limitations such as limited generalisability and lack of statistical power. The objective of this national population‐based study was to describe the characteristics, management and outcomes of women giving birth at very advanced maternal age in the UK and to estimate the risk of adverse outcomes attributable to very advanced maternal age.

Methods

A national, population‐based cohort study was conducted. The cohort included any pregnant woman in the UK at 20 weeks of gestation or more, who was of very advanced maternal age. Although very advanced maternal age has generally been used to refer to women aged ≥45 years, for pragmatic reasons, and so as to not over‐burden reporting clinicians, we defined very advanced maternal age as women aged ≥48 years at their date of delivery. The cohort was identified through the monthly mailing of the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) between 1 July 2013 and 30 June 2014. The UKOSS methodology has been described in detail elsewhere.8 Briefly, cards were sent to nominated clinicians (midwives, risk management midwives, obstetricians and anaesthetists) in each of the UK's obstetrician‐led maternity units requesting the number of pregnant woman of very advanced maternal age they had seen that month. On reporting a pregnancy in a woman of very advanced maternal age, clinicians were sent a data collection form to complete seeking additional information concerning the characteristics, management and outcomes of the woman concerned. Reporting clinicians were also asked to identify and complete an identical data collection form for comparison women, defined as the two pregnant women at 20 weeks of gestation or more who were <48 years of age at their estimated date of delivery and who delivered immediately before the older woman in the same hospital. All data requested were anonymous. Information on woman's year of birth and expected date of delivery was used to identify duplicate reports. A total of five reminders were sent if complete forms were not returned.

All analyses were conducted using STATA v 13 software (Statacorp, College Station, TX, USA). Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were estimated throughout using unconditional logistic regression. Odds ratios were adjusted for potential confounding factors if there was a pre‐existing hypothesis or evidence that the factors were potential confounders or mediators of the relationship between advanced maternal age and the outcome in question. To help examine the relative influence of the potential confounders and mediators on the association between maternal age and the outcome in question, models were adjusted in a hierarchical fashion: model 1 adjusted for sociodemographic factors; model 2 additionally adjusted for previous medical history; and model 3 additionally adjusted for relevant pregnancy‐related factors. ‘Missing’ was included as an extra category for variables that had ≥10% missing data. Continuous variables were tested for evidence of departure from linearity by the addition of first‐order fractional polynomials to the model and subsequent likelihood ratio testing. Continuous variables that showed evidence of nonlinearity were treated and presented as categorical in the analysis, whereas those showing evidence of linearity were treated as continuous linear terms when adjusting for them in the analysis but presented as categorical for ease of interpretation. Plausible interactions were tested in the full regression model by the addition of interaction terms and subsequent likelihood ratio testing on removal, with a P‐value <0.01 considered as evidence of significant interaction to account for multiple testing.

Women who initially had a multiple pregnancy but then had fetal reduction were classified in the analysis according to the number of fetuses left after the reduction. Spontaneous first‐trimester losses in women known initially to have a multiple pregnancy were classified in the analysis according to the post‐loss number of fetuses. Second‐trimester losses in a multiple pregnancy were classified according to the pre‐loss number of fetuses in the main analysis, but were not included when examining neonatal outcomes unless they occurred after 24 weeks. Logistic regression using robust standard errors to allow for non‐independence of neonates from multiple births was used when comparing neonatal outcomes.

Using the most recent national birth data3, 9, 10 we anticipated identifying 406 women aged ≥48 years at their date of delivery and 812 comparison women. With these numbers of women the study would have had an estimated power of 80% at the 5% level of statistical significance to detect odds ratios of ≥1.5 and ≥2.0, assuming outcomes have an incidence of 40% and 5%, respectively. The actual number of older and comparison women identified during the study gave an estimated power of 80% at the 5% level of significance to detect odds ratios of ≥1.6 and ≥2.5, assuming the same outcome incidence levels.

Results

All eligible hospitals with obstetrician‐led maternity units contributed data to UKOSS during the study period (100% response), notifying 351 women of very advanced maternal age. Excluding those subsequently reported by clinicians as not fulfilling the inclusion criteria, data collection forms were obtained for 89% of the notified women (Figure S1) and data were received for 454 comparison women. A total of 233 women of very advanced maternal age were identified.

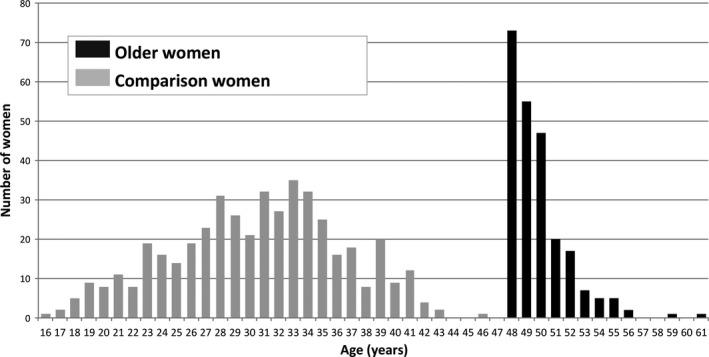

The median age of the older women was 49 years (range 48–61 years) whereas the median age of the comparison women was 31 years (range 16–46 years) (Figure 1). Older women were significantly more likely than comparison women to be overweight or obese, to be nonsmokers, to have had previous uterine surgery not including previous caesarean section, to have previous or pre‐existing medical condition(s), to be nulliparous, to have a multiple pregnancy, and to have conceived following assisted conception (Table 1). Of the 50 older women who conceived without assisted conception, 14 (61% of the 23 in whom this was known) had planned pregnancies. Of the 176 older women known to have conceived following assisted conception, 51% (61/119, 57 women with no information provided) had the assisted conception performed outside the UK, 91% (137/151, 25 with no information provided) had used egg donation, 21% (22/104, 72 with no information provided) had used sperm donation, and 97% (147/152, 24 with no information provided) underwent in vitro fertilisation/intracytoplasmic injection (IVF/ICSI). Of the 147 women who had IVF/ICSI, 55 women had the number of embryos transferred recorded: 22 had one embryo transferred, 25 had two embryos transferred, six had three embryos transferred and two had four embryos transferred. Excluding first‐trimester spontaneous losses and subsequent fetal reductions, 15 of the 30 women who had more than one embryo transferred went on to have a multiple pregnancy. The characteristics of the older women in our study were comparable to the available national data for England and Wales on women giving birth at very advanced maternal age (Table 2) with the exception of the proportion of women who were married/in a civil partnership with one or more previous live‐born children, which was lower in our study population.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of older and comparison women.

Table 1.

Characteristics of older and comparison women

| Characteristic | Number (%)a of older women (n = 233) | Number (%)a of comparison women (n = 454) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Ethnic group | ||||

| White | 165 (71) | 323 (71) | 1 | |

| Non‐White | 67 (29) | 129 (29) | 1.02 (0.72–1.44) | 0.9259 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married or cohabiting | 194 (85) | 375 (84) | 1 | |

| Single | 35 (15) | 71 (16) | 0.95 (0.61–1.48) | 0.8299 |

| Socio‐economic group | ||||

| Managerial and professional occupations | 91 (39) | 144 (32) | 1 | |

| Other | 103 (44) | 231 (51) | 0.71 (0.50–1.00) | 0.0511 |

| Missing | 39 (17) | 79 (17) | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||

| <25 | 101 (44) | 260 (58) | 1 | |

| 25–29.9 | 75 (33) | 103 (23) | 1.87 (1.29–2.73) | 0.0011 |

| ≥30 | 52 (23) | 85 (19) | 1.57 (1.04–2.38) | 0.0318 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never/ex smoker | 226 (99) | 407 (90) | 1 | |

| Smoked during pregnancy | 3 (1) | 45 (10) | 0.12 (0.04–0.39) | 0.0004 |

| Previous medical history | ||||

| Previous uterine surgery not including previous caesarean section | ||||

| No | 168 (74) | 418 (93) | 1 | |

| Yes | 60 (26) | 33 (7) | 4.52 (2.85–7.17) | <0.0001 |

| Previous or pre‐existing medical condition | ||||

| No | 129 (56) | 328 (72) | 1 | |

| Yes | 101 (44) | 126 (28) | 2.04 (1.46–2.84) | <0.0001 |

| Pregnancy‐related characteristics | ||||

| Parity | ||||

| 0 | 122 (53) | 200 (44) | 1 | |

| 1 or more | 108 (47) | 252 (56) | 0.7 (0.51–0.97) | 0.0299 |

| Previous caesarean section | ||||

| No | 179 (79) | 379 (84) | 1 | |

| Yes | 49 (21) | 72 (16) | 1.44 (0.96–2.16) | 0.0765 |

| Multiple pregnancy | ||||

| No | 189 (82) | 444 (98) | 1 | |

| Yes | 41 (18) | 10 (2) | 9.63 (4.73–19.63) | <0.0001 |

| Conceived following assisted conception | ||||

| No | 50 (22) | 425 (96) | 1 | |

| Yes | 176 (78) | 19 (4) | 78.74 (45.13–137.38) | <0.0001 |

Percentage of individuals with complete data unless missing category shown.

Table 2.

Comparison of the characteristics of older women identified by UKOSS with available national data on women giving birth at very advanced maternal age

| Characteristic | UKOSS number (%)a of older women (n = 233) | National datab on number (%)a of older women (n = 384) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status | |||

| Married/civil partnership | 127 (55) | 246 (64) | |

| Single | 102 (29) | 138 (36) | 0.0754 |

| Number of previous live‐born children within marriage/civil partnership | |||

| 0 | 67 (53) | 94 (38) | |

| 1 or more | 60 (47) | 152 (62) | 0.0056 |

| Multiple pregnancy | |||

| No | 189 (82) | 332 (86) | |

| Yes | 41 (18) | 52 (14) | 0.185 |

| Age of mother (years) | |||

| 48 | 73 (31) | 139 (36) | 0.2041 |

| 49 | 55 (24) | 100 (26) | 0.5793 |

| ≥50 | 105 (45) | 145 (38) | 0.0861 |

Percentage of individuals with complete data.

Data for maternities in England and Wales 2013, Office of National Statistics ad hoc data and analysis 2015.

Older women were significantly more likely than the comparison women to have a plan at booking for more than the recommended number of antenatal visits for low‐risk women 82% (185/226) versus 30% (133/447), P < 0.001). Maternal age was the commonest reason given for older women having more antenatal visits (82%, 152/185), followed by underlying medical condition/previous obstetric history (32%, 60/185). The proportion of older women who received care at their usual hospital for their place of residence was not significantly different from the proportion seen in the comparison women (86%, 197/228, versus 91%, 409/451, P = 0.089). Of the older women who did not have their care at their usual hospital, reasons included patient preference (n = 20), referral to a tertiary centre because of underlying medical conditions (n = 4) and maternal age (n = 2). Eighty‐seven percent of older women (196/225) had antenatal screening; 74% had a nuchal translucency test, 57% had serum screening, 1% had chorionic villus sampling, 5% had amniocentesis and 77% had an 18‐ to 20‐week anomaly scan. The proportions seen in the comparison women were comparable with the exception of amniocentesis, which was significantly less likely in the comparison women, occurring in just 1% (P = 0.009). Older women were also more likely than the comparison women to have a third‐trimester ultrasound performed (87%, 199/228 versus 50%, 222/445, P < 0.001). Reasons for a third‐trimester ultrasound included concerns about the fetus, e.g. fetal growth (n = 113), routine diabetic monitoring (n = 15), other maternal condition (n = 9), abnormal presentation (n = 5) and pregnancy complication (n = 17).

Table 3 shows the pregnancy complications experienced by the older and comparison women. Unadjusted analysis suggests that older women were more likely than comparison women to have a range of complications including gestational hypertensive disorders, gestational diabetes, postpartum haemorrhage, caesarean delivery, iatrogenic and spontaneous preterm delivery and intensive therapy unit (ITU) admission. With the exception of gestational diabetes, caesarean delivery and ITU admission, however, these effects were attenuated and became nonsignificant largely after adjustment for pregnancy‐related characteristics. For effects that became nonsignificant after adjustment for pregnancy‐related characteristics, further analysis was performed in which adjustment was made for sociodemographic factors, previous medical history and relevant pregnancy‐related factors one at a time (Table S1); while parity and previous caesarean section, where relevant, had little impact, all of the effects became nonsignificant after adjustment for how the woman conceived and some became nonsignificant following adjustment for multiple pregnancy. An analysis including just singleton pregnancies (Model 4, Table 3) reflected very similar results with the exception of postpartum haemorrhage, which remained significant even after full adjustment. There was evidence of significant interaction between caesarean delivery and parity: the raised odds of having a caesarean delivery were only apparent in nulliparous older women (adjusted OR [aOR] 9.90, 95% CI 3.64–26.92 in nulliparous women; aOR 0.71, 95% CI 0.31–1.66 in parous women). No other significant interactions were found. Among the older women who had a caesarean delivery, maternal age was the primary indication for 21% (36/175). Other indications included fetal compromise (19%, 33/175), maternal compromise (14%, 25/175), failure to progress (14%, 24/175), abnormal presentation (10%, 18/175), previous caesarean section (9%, 16/175) and maternal request (5%, 9/175).

Table 3.

Pregnancy complications of older and comparison women in all women and in women with singleton pregnancies only

| Number (%)a of older women (n = 233) | Number (%)a of comparison women (n = 454) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P‐value | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P‐value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P‐value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P‐value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P‐value | |||||

| Any gestational hypertensive disorder | ||||||||||||

| No | 196 (85) | 430 (95) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 34 (15) | 24 (5) | 3.11 (1.79–5.38) | <0.0001 | 2.88 (1.63–5.09) | 0.0003 | 2.84 (1.60–5.06) | 0.0004 | 2.13 (0.75–6.02) | 0.1535 | 1.82 (0.56–5.99) | 0.3221 |

| Any gestational hypertensive disorder managed by early delivery | ||||||||||||

| No | 219 (95) | 442 (97) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 11 (5) | 12 (3) | 1.85 (0.80–4.26) | 0.1482 | 1.72 (0.74–4.01) | 0.2078 | 1.8 (0.77–4.22) | 0.1783 | 1.28 (0.27–6.01) | 0.7536 | 1.49 (0.27–8.28) | 0.6462 |

| Pregnancy induced hypertension | ||||||||||||

| No | 209 (91) | 440 (97) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 21 (9) | 14 (3) | 3.16 (1.57–6.33) | 0.0012 | 2.85 (1.38–5.88) | 0.0046 | 2.81 (1.35–5.84) | 0.0058 | 2.82 (0.79–10.05) | 0.1093 | 2.53 (0.63–10.21) | 0.1912 |

| Preeclampsia | ||||||||||||

| No | 217 (94) | 444 (98) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 13 (6) | 10 (2) | 2.66 (1.15–6.16) | 0.0225 | 2.55 (1.07–6.07) | 0.0346 | 2.53 (1.05–6.09) | 0.0379 | 1.16 (0.22–6.09) | 0.8577 | 0.82 (0.10–6.44) | 0.8483 |

| Gestational diabetes | ||||||||||||

| No | 188 (82) | 436 (96) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 42 (18) | 18 (4) | 5.41 (3.04–9.65) | <0.0001 | 4.97 (2.73–9.04) | <0.0001 | 4.78 (2.61–8.77) | <0.0001 | 4.81 (1.93–12.00) | 0.0007 | 3.41 (1.27–9.19) | 0.0151 |

| Gestational diabetes requiring insulin | ||||||||||||

| No | 221 (96) | 452 (100) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 9 (4) | 2 (0) | 9.2 (1.97–42.96) | 0.0047 | 8.12 (1.72–38.31) | 0.0081 | 7.54 (1.57–36.17) | 0.0115 | 3.64 (0.50–26.55) | 0.2033 | 3.85 (0.49–30.18) | 0.1999 |

| Placenta praevia | ||||||||||||

| No | 222 (97) | 453 (100) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 8 (3) | 0 (0) | ||||||||||

| Placental abruption | ||||||||||||

| No | 226 (99) | 451 (100) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 3 (1) | 2 (0) | 2.99 (0.50–18.04) | 0.2316 | 4.7 (0.65–34.09) | 0.1258 | 4.31 (0.60–30.89)¥ | 0.1456 | 1.2 (0.08–19.02)# | 0.8963 | 1.11 (0.07–18.70)¥,# | 0.941 |

| Diagnosed postpartum haemorrhage | ||||||||||||

| No | 169 (74) | 385 (85) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 59 (26) | 69 (15) | 1.95 (1.32–2.88) | 0.0009 | 1.89 (1.26–2.84) | 0.0022 | 1.74 (1.13–2.66)¥ | 0.0114 | 2.03 (0.97–4.27)# | 0.0603 | 2.45 (1.10–5.44)¥,# | 0.0279 |

| Diagnosed postpartum haemorrhage requring blood transfusion | ||||||||||||

| No | 210 (94) | 441 (98) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 14 (6) | 8 (2) | 3.67 (1.52–8.90) | 0.0039 | 3.53 (1.39–8.92) | 0.0077 | 2.30 (0.87–6.05)¥ | 0.0916 | 4.33 (0.94–19.96)# | 0.06 | 6.39 (1.19–34.42)¥,# | 0.0308 |

| Thrombotic event | ||||||||||||

| No | 229 (100) | 453 (100) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | ||||||||||

| Labour induced | ||||||||||||

| No | 156 (69) | 321 (71) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 71 (31) | 133 (29) | 1.1 (0.78–1.55) | 0.5945 | 1.18 (0.82–1.69) | 0.3711 | 1.1 (0.75–1.61)¥ | 0.6235 | 1.91 (1.03–3.54)# | 0.0401 | 1.9 (0.98–3.65)¥,# | 0.056 |

| Caesarean delivery | ||||||||||||

| No | 50 (22) | 305 (67) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 178 (78) | 149 (33) | 7.29 (5.03–10.55) | <0.0001 | 6.41 (4.39–9.37) | <0.0001 | 5.9 (3.98–8.75)¥ | <0.0001 | 2.78 (1.44–5.37)# | 0.0024 | 2.98 (1.47–6.05)¥,# | 0.0024 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | ||||||||||||

| Term (37+ weeks) | 176 (78) | 420 (93) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Iatrogenic preterm (<37 weeks) | 32 (14) | 17 (4) | 4.49 (2.43–8.30) | <0.0001 | 4.49 (2.39–8.43) | <0.0001 | 4.23 (2.19–8.18)¥ | <0.0001 | 1.01 (0.30–3.45)# | 0.9845 | 1.72 (0.40–7.34) ¥,# | 0.4671 |

| Spontaneous preterm (<37 weeks) | 18 (8) | 17 (4) | 2.53 (1.27–5.02) | 0.0081 | 2.44 (1.17–5.09) | 0.0169 | 2.34 (1.09–5.00)¥ | 0.0287 | 1.11 (0.28–4.45)# | 0.8832 | 0.75 (0.14–4.15) ¥,# | 0.7431 |

| Admitted to ITU | ||||||||||||

| No | 224 (97) | 453 (100) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 6 (3) | 1 (0) | 12.13 (1.45–101.40) | 0.0212 | 10.98 (1.28–94.01) | 0.0288 | 10.96 (1.28–94.17) | 0.0291 | 33.53 (2.73–412.24) | 0.0061 | 37.53 (2.98–472.18) | 0.005 |

| In nulliparous women | ||||||||||||

| Caesarean delivery | ||||||||||||

| No | 1 | |||||||||||

| Yes | 9.90 (3.64–26.92) | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| In women parity 1+ | ||||||||||||

| Caesarean delivery | ||||||||||||

| No | 1 | |||||||||||

| Yes | 0.71 (0.31–1.66) | 0.431 | ||||||||||

Model 1: Adjusted for socio‐demographic factors (Ethnic group, marital status, socio‐economic group, body mass index and smoking status).

Model 2: Adjusted for variables included in model 1 plus previous medical history (previous uterine surgery not including previous caesarean section and previous or preexisting medical conditions where ¥ is shown, or just previous or preexisting medical conditions where ¥ is not shown).

Model 3: Adjusted for variables included in model 2 plus pregnancy related factors (parity, multiple pregnancy, how conceived and previous caesarean delivery where # is shown, or just parity, multiple pregnancy and how conceived if # is not shown.

Model 4: Women with singleton pregnacies only, adjusted for socio‐demographic factors (Ethnic group, marital status, socio‐economic group, body mass index and smoking status) plus previous medical history (previous uterine surgery not including previous caesarean section and previous or preexisting medical conditions where ¥ is shown, or just previous or preexisting medical conditions where ¥ is not shown) plus pregnancy related factors (parity, how conceived and previous caesarean delivery where # is shown, or just parity and how conceived if # not shown).

Statistically significant values are bolded.

Percentage of individuals with complete data.

Two of the older women had fetal reduction, one from three to two fetuses and the other from three to one fetus. Five of the older women were known to initially have twin pregnancies but two spontaneously lost one twin in the first trimester, two spontaneously lost one twin in the second trimester before 24 weeks of gestation, and one lost both twins in the second trimester. Three other older women experienced spontaneous loss in the second trimester before 24 weeks: one woman initially had a triplet pregnancy but spontaneously lost one of the triplets in the second trimester before 24 weeks, and the other two were singleton pregnancies. Among the older women, this effectively left a total of 268 fetuses surviving beyond 24 weeks of gestation (35 sets of twins, three sets of triplets and 189 singletons). Of these 268 fetuses, three were stillborn antepartum: one was a set of twins where both twins were stillborn. A further two of the fetuses died shortly after birth following very preterm delivery (<28 weeks of gestation), equating to an overall perinatal mortality rate of 18.7 per 1000 (95% CI 6.1–42.9). This was more than three times the national rate of 5.5 per 100011 (relative risk 3.33, 95% CI 1.40–7.93). The perinatal mortality rate among singletons was 15.9 per 1000 (95% CI 3.3–45.7), also statistically significantly higher than the national perinatal mortality rate among singletons of 5.2 per 100011 (relative risk 3.03, 95% CI 0.99–9.33, P = 0.043).

The proportion of fetuses surviving beyond 24 weeks of gestation that had a congenital anomaly was similar between the older women and the comparison women (1.9%, 5/263 versus 1.5%, 7/460, P = 0.702), as was the proportion that had other major complications such as respiratory distress syndrome and severe infection (2%, 4/205 versus 3.8%, 13/344, P = 0.240). The proportion of fetuses that had a low birthweight (<2500 g) was higher among those born to older women compared with comparison women (32%, 85/267 versus 8%, 38/463, P < 0.001), although this difference disappeared after controlling for gestational age at delivery.

Discussion

Main findings

This study suggests that women giving birth at very advanced maternal age have a higher risk of having a range of pregnancy complications including gestational hypertensive disorders, gestational diabetes, postpartum haemorrhage, caesarean delivery, iatrogenic and spontaneous preterm delivery and ITU admission. With the exception of gestational diabetes, caesarean delivery and ITU admission, these increased risks appear to be largely explained by the higher rate of multiple pregnancy or use of assisted conception observed in the older women.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of our study is its prospective population‐based national design, which reduces the possibility of bias associated with hospital‐based studies. We also had the advantage of not relying on coded data from routine hospital administrative systems, which has been shown to have a number of limitations.12 Despite the active monthly nature of the UKOSS data collection system and the presence of several reporting clinicians in each hospital, comparison with the most recent national birth data, which does not cover the entire study period, suggests that we have under‐ascertained women giving birth at very advanced maternal age by up to 30%. Comparison of the characteristics of women giving birth at very advanced maternal age in our study with the available national data for England and Wales on women giving birth at very advanced maternal age suggested that our study may have under‐ascertained parous older women, although other characteristics are comparable. However, adjustment of our results for parity did not have a meaningful impact, suggesting that this is unlikely to have had a substantive effect.

Interpretation (in light of other evidence)

Our finding that women giving birth aged 48 years and older have a higher risk of having a range of pregnancy complications is comparable to the limited number of studies that have assessed outcomes in high‐income countries in relation to very advanced maternal age (≥45 years).7, 13 Of particular note is the fact that the odds of the majority of these complications were attenuated or disappeared after adjustment for mode of conception and multiple pregnancy, which has important implications for counselling and practice in assisted reproduction services. Half of the women who had double embryo transfer went on to have a multiple pregnancy, which is higher than the rate of 29% reported in a meta‐analysis of trials of double embryo transfer,14 potentially due to the use of ovum donation in these women. It cannot therefore be assumed that multiple pregnancy is less likely in this population than in women of younger ages undergoing assisted reproduction. Recommendations regarding assisted conception including egg donation in older mothers, as well as single embryo transfer should take these findings into account.

Adjustment for medical co‐morbidities had little impact on the odds ratios we observed, suggesting that the increased risk of pregnancy complications is unlikely to be solely due to the population of women who undergo assisted reproduction being less healthy than those who conceive spontaneously. Nearly one in six women giving birth at very advanced maternal age in our study developed a gestational hypertensive disorder with nearly 1 in 10 developing pregnancy‐induced hypertension and just over 1 in 20 developing pre‐eclampsia. Although these rates were around three‐fold higher than in the comparison women, they are in the lower range of the rates reported for women aged ≥45 years,7, 13 but generally higher than rates quoted in contemporary studies for women of more modest advanced maternal age (≥35 or ≥40 years).15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Nearly one in five women giving birth at very advanced maternal age in our study developed gestational diabetes, around five‐fold higher than the rate in the comparison group with differences persisting after adjustment for potential confounding and mediating factors. This rate is in the higher range of the rates that have been reported.7, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Our rate of postpartum haemorrhage, diagnosed in just over one‐quarter of women of very advanced maternal age, was also higher than those quoted.13, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21 These differences may reflect disparities in estimating and defining postpartum haemorrhage.22

A recent systematic review identified a higher risk of caesarean section among women of advanced maternal age (mainly ≥35 years), although the heterogeneity among the included studies precluded a pooled estimate of the risk.23 Our caesarean section rate is at the higher end of the range of those reported for women aged ≥45 years,7, 13 and may reflect a tendency for clinicians to offer caesarean delivery in this extreme age group. Indeed, advanced maternal age was the commonest indication, recorded as the primary reason for around one‐fifth of the caesarean deliveries.

Just over one in five women of very advanced maternal age in our study delivered preterm, with the rates of both iatrogenic and spontaneous preterm delivery higher than in the comparison women, differences that appear to be largely explained by differences in pregnancy‐related characteristics. Most of the previous literature has reported an association between advanced maternal age and preterm delivery without separating out type of preterm delivery; our estimated rate of preterm delivery is in the higher range of the rates reported for women aged ≥45 years7, 13 and is generally higher than in studies examining women of more modestly advanced maternal age.15, 18, 19, 24, 25 Except for the higher rate of low birthweight infants, which appears to be largely linked to the high preterm delivery rate, other infant outcomes were comparable between the older and comparison women in our study. However, the perinatal mortality rate was significantly raised in the older women in comparison to the national rate. Other studies have reported an increase in the risk of perinatal mortality among women of advanced maternal age, although the absolute increase in risk appears to be small.7, 13, 25, 26

Conclusion

Although having a baby at very advanced maternal age is currently uncommon in the UK, developments in artificial reproductive technologies are contributing to an increasing incidence of pregnancies in women outside of the normal reproductive age. Women giving birth at very advanced maternal age have a higher risk of having a range of pregnancy complications in comparison to younger women, including a higher risk of gestational hypertensive disorders, gestational diabetes, postpartum haemorrhage, caesarean delivery, iatrogenic and spontaneous preterm delivery and ITU admission. With the exception of gestational diabetes, caesarean delivery and ITU admission, these increased risks appear to be largely explained by the higher rate of multiple pregnancy or the use of assisted conception observed in the older women, all of which are inextricably inter‐related to older maternal age, with older age leading to a need for IVF if conception is to occur and age itself and IVF leading to an increased risk of multiple birth. These findings should be considered when counselling and managing women of very advanced maternal age. They also show the implications for maternity services of having a baby at very advanced maternal age. There may be a place for considering fetal reduction in women of very advanced age with multiple pregnancies although the long‐term effect of fetal reduction on surviving infants is unclear and this needs further research. Recommendations regarding assisted conception including egg donation in older mothers, as well as single embryo transfer, should take these findings into account.

Disclosure of interests

None declared. Completed disclosure of interests form available to view online as supporting information.

Contribution to authorship

KEF designed the study, coded the data, carried out the analysis and wrote the manuscript. DT and JJK assisted with the design of the study and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. MK conceived and designed the study and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. MK will act as guarantor.

Details of ethical approval

The North London Research Ethics Committee 1 approved the study (reference 10/H0717/20) on 06/04/2010.

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under the ‘Beyond maternal death: improving the quality of maternity care through national studies of “near‐miss” maternal morbidity’ programme (programme grant RP‐PG‐0608‐10038). Marian Knight is funded by an NIHR Research Professorship. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s), and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NHIR or the Department of Health. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the article.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Case reporting and completeness of data collection.

Table S1. Further analysis of pregnancy complications, adjusting for sociodemographic factors, previous medical history and relevant pregnancy‐related factors one at a time.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) reporting clinicians who notified cases and completed the data‐collection forms, without whose contribution it would not have been possible to carry out this study.

Fitzpatrick KE, Tuffnell D, Kurinczuk JJ, Knight M. Pregnancy at very advanced maternal age: a UK population‐based cohort study. BJOG 2016;124:1097–1106.

References

- 1. Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. Mean age of mother, 1970–2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2002;51:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Breart G. Delayed childbearing. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1997;75:71–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Office for National Statistics . Live Births In England and Wales by Characteristics of Mother 1, 2013. London: Office for National Statistics, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balasch J, Gratacos E. Delayed childbearing: effects on fertility and the outcome of pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2012;24:187–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Montan S. Increased risk in the elderly parturient. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2007;19:110–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hansen JP. Older maternal age and pregnancy outcome: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1986;41:726–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carolan M. Maternal age ≥45 years and maternal and perinatal outcomes: a review of the evidence. Midwifery 2013;29:479–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Knight M, Kurinczuk JJ, Tuffnell D, Brocklehurst P. The UK obstetric surveillance system for rare disorders of pregnancy. BJOG 2005;112:263–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. General Register Office for Scotland . Vital Events Reference Tables 2013. Edinburgh: General Register Office for Scotland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency . Registrar General Annual Report 2013. Belfast: Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Manktelow BM, Smith LK, Evans TA, Hyman‐Taylor P, Kurinczuk JJ, Field DJ, et al. Perinatal Mortality Surveillance Report UK Perinatal Deaths for births from January to December 2013. Leicester: The Infant Mortality and Morbidity Group, Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Knight M. Studies using routine data versus specific data collection: what can we learn about the epidemiology of eclampsia and the impact of changes in management of gestational hypertensive disorders? Pregnancy Hypertens 2011;1:109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carolan MC, Davey MA, Biro M, Kealy M. Very advanced maternal age and morbidity in Victoria, Australia: a population based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McLernon DJ, Harrild K, Bergh C, Davies MJ, de Neubourg D, Dumoulin JC, et al. Clinical effectiveness of elective single versus double embryo transfer: meta‐analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. BMJ 2010;341:c6945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ciancimino L, Lagana AS, Chiofalo B, Granese R, Grasso R, Triolo O. Would it be too late? A retrospective case–control analysis to evaluate maternal–fetal outcomes in advanced maternal age. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014;290:1109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khalil A, Syngelaki A, Maiz N, Zinevich Y, Nicolaides KH. Maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcome: a cohort study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013;42:634–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Biro MA, Davey MA, Carolan M, Kealy M. Advanced maternal age and obstetric morbidity for women giving birth in Victoria, Australia: a population‐based study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2012;52:229–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yogev Y, Melamed N, Bardin R, Tenenbaum‐Gavish K, Ben‐Shitrit G, Ben‐Haroush A. Pregnancy outcome at extremely advanced maternal age. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;203:558 e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cleary‐Goldman J, Malone FD, Vidaver J, Ball RH, Nyberg DA, Comstock CH, et al. Impact of maternal age on obstetric outcome. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:983–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carolan M, Davey MA, Biro MA, Kealy M. Older maternal age and intervention in labor: a population‐based study comparing older and younger first‐time mothers in Victoria, Australia. Birth 2011;38:24–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Callaway LK, Lust K, McIntyre HD. Pregnancy outcomes in women of very advanced maternal age. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2005;45:12–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rath WH. Postpartum hemorrhage – update on problems of definitions and diagnosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011;90:421–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bayrampour H, Heaman M. Advanced maternal age and the risk of cesarean birth: a systematic review. Birth 2010;37:219–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kenny LC, Lavender T, McNamee R, O'Neill SM, Mills T, Khashan AS. Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcome: evidence from a large contemporary cohort. PLoS One 2013;8:e56583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carolan M, Frankowska D. Advanced maternal age and adverse perinatal outcome: a review of the evidence. Midwifery 2011;27:793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang L, Sauve R, Birkett N, Fergusson D, van Walraven C. Maternal age and risk of stillbirth: a systematic review. CMAJ 2008;178:165–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Case reporting and completeness of data collection.

Table S1. Further analysis of pregnancy complications, adjusting for sociodemographic factors, previous medical history and relevant pregnancy‐related factors one at a time.