Abstract

A series of 29 patients undergoing treatment for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1 infection with pegylated alpha-2a interferon plus ribavirin were studied for patterns of response to antiviral therapy and viral quasispecies evolution. All patients were treatment naive and had chronic inflammation and fibrosis on biopsy. As part of an analysis of pretreatment variables that might affect the outcome of treatment, genetic heterogeneity within the viral E1-E2 glycoprotein region (nucleotides 851 to 2280) was assessed by sequencing 10 to 15 quasispecies clones per patient from serum-derived PCR products. Genetic parameters were examined with respect to response to therapy based on serum viral RNA loads at 12 weeks (early viral response) and at 24 weeks posttreatment (sustained viral response). Nucleotide and amino acid quasispecies complexities of the hypervariable region 1 (HVR-1) were less in the responder group in comparison to the nonresponder group at 12 weeks, and genetic diversity was also less both within and outside of the HVR-1, with the difference being most pronounced for the non-HVR-1 region of E2. However, these genetic parameters did not distinguish responders from nonresponders for sustained viral responses. Follow-up studies of genetic heterogeneity based on the HVR-1 in selected responders and nonresponders while on therapy revealed greater evolutionary drift in the responder subgroup. The pretreatment population sequences for the NS5A interferon sensitivity determinant region were also analyzed for all patients, but no correlations were found between treatment response and any distinct genetic markers. These findings support previous studies indicating a high level of genetic heterogeneity among chronically infected HCV patients. One interpretation of these data is that early viral responses are governed to some extent by viral factors, whereas sustained responses may be more influenced by host factors, in addition to effects of viral complexity and diversity.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is responsible for at least 4 million cases of chronic active viral hepatitis in the United States and a worldwide burden of as many as 300 million cases (3, 4, 45). Infection with HCV is followed by the occurrence of persistent disease in the majority of cases, which is associated with a viremia that reflects productive replication of virus in the liver, estimated to yield as many as a trillion virus particles per day (28). Factors involved in either the spontaneous clearance of HCV or clearance associated with antiviral therapy have been partially elucidated and involve both viral and host determinants (8, 9, 43, 46). Among viral factors, it has been demonstrated that genetic heterogeneity of the virus at the level of quasispecies populations impacts on the evolution of chronic infection, with the development of more complex populations of virus associated with an inability to clear acute infection (8). Viral genetic heterogeneity has been reported in some but not all cases to correlate with the progression of liver disease caused by HCV (18, 23, 27, 47). An increase in genetic heterogeneity has also been linked to a poor response to antiviral therapy, including studies of patients with both genotype 1 and non-genotype 1 infections (9). The complexity and diversity of HCV isolates in such studies is based primarily on sequence differences within the hypervariable regions of the E2 protein. Viral variation, inherently generated by error-prone activity of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, is presumably further driven by immune pressures involving neutralizing antibody, cytotoxic lymphocytes, alpha/beta interferons, and perhaps other host factors that affect the efficiency of viral replication and allow selection of viral variants.

In the present study, we addressed the question of whether the extent of genetic heterogeneity of HCV genotype 1 isolates among patients with chronic infection bears any relationship to the response to antiviral therapy with the pegylated alpha-2a interferon. Although many studies have analyzed this question in the context of standard interferon therapy, there are not abundant data on the effects of the long-acting forms of alpha interferon. A total of 29 patients undergoing a 48-week treatment period with a combination of pegylated alpha-2a interferon and ribavirin were studied for their patterns of response based on viral RNA levels in serum. To determine whether viral factors affect the treatment response, we analyzed the pretreatment viral genetic heterogeneity using a segment of ca. 1,400 nucleotides from the E1/E2 region. We also followed up on a selected subset of patients in the responder and nonresponder groups to investigate whether the pattern of quasispecies evolution differed between these two groups while on therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical protocol.

All patients included in the present study were selected from the clinical service of the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the St. Louis University Health Sciences Center. Patients were enrolled under informed consent and in accordance with institutional guidelines for protection of human subjects as recommended by the University Institutional Review Board. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had chronic HCV infection (either genotype 1a or genotype 1b), with no history of prior alpha interferon therapy, and with evidence of chronic inflammation and fibrosis on liver biopsy obtained at time of entry or prior to referral for treatment and evidence of ongoing liver injury manifest by elevated liver enzymes. All patients received pegylated alpha-2a interferon (Pegasys, Roche) at 180 μg per week and ribavirin (1,000 to 1,200 mg/day) for 48 weeks and were monitored at the clinic at frequent intervals to determine HCV RNA in serum and routine clinical laboratory parameters. Patients were further monitored in the study for at least 24 weeks posttreatment as part of the study protocol. HCV RNA levels in serum were determined by using the Roche Monitor assay. Other clinical laboratory tests included determination of serum rheumatoid factor, serum cryoglobulins, and serum liver transaminases. Liver biopsy specimens were evaluated by experienced pathologists for inflammation and fibrosis by using standard grading scales (39).

Molecular cloning of E1/E2 and HVR-1.

Total RNA was extracted from 100 μl of serum as previously described (7). Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was performed to amplify a 1.37-kb fragment encompassing E1 and most of the E2 region. The contamination-prevention measures suggested by Kwok and Higuchi were adopted in all procedures (24). Briefly, 5 μl of extracted serum RNA was mixed with 1 μl of 50 mmol of MgCl2/liter, 2 μl of 10× PCR buffer, 1 μl of 100 mmol of dithiothreitol/liter, 0.3 μl of 100 μmol of deoxynucleoside triphosphates/liter, 0.2 μl of 100 μmol of reverse primer DPR1 (Table 1) /liter, 16 U of RNasin, and 80 U of SuperScript II (Gibco-BRL) in a total 20-μl reaction volume, followed by incubation at 42°C for 60 min in a thermal cycler DNA 480 (Perkin-Elmer-Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.). First-round PCR was performed by mixing 20 μl of RT reaction mixture with 30 μl of matrix containing 3 μl of 10× PCR buffer, 0.2 μl of 100 μmol of deoxynucleoside triphosphates/liter, 0.2 μl of 100 μmol of the indicated primers (Table 1)/liter, and 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer-Cetus). Files were programmed for 95°C for 4 min, followed by 5 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min, with a final 7-min extension at 72°C. Then, 5 μl of product from the first round was used as the template for second-round amplification as described above, except the concentration of MgCl2 was adjusted to 2.5 μmol/liter, and the primers were replaced by different inner sets for HCV genotype 1a or HCV genotype 1b (Table 1). Primer positions were according to HCV J4 strain (GenBank accession no. D10750), with degenerate bases matched to the standard International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) codes. For generation of short PCR fragments (494 bp) encompassing hypervariable region 1 (HVR-1), a second set of nested primers was used in conjunction with RT-PCR conditions similar to those described above for the 1,400-bp fragments, except that elongation times were restricted to 30 s. The primer sequences for the short product are shown in Table 1, with numbering according to HCV J4 strain (GenBank accession no. D10750).

TABLE 1.

Nested RT-PCR primers used for the amplification of HCV domains E1/E2, HVR-1, and NS5aa

| Domain and size (bp) | PCR | Primer | Polarity | Sequence (5′-3′) | Genotype(s) | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1/E2 (1,359) | RT | DPR1 | Antisense | AGCAGNAGTTTGGTGATGTC | 1a/1b | 3000-3019 |

| First round | CF1 | Sense | GACGGCGTGAACTATGCAACAGG | 1a/1b | 819-841 | |

| EAR1 | Antisense | TCCAGTTGCAGGCAGCWTCCAGCC | 1a | 2257-2280 | ||

| EBR1 | Antisense | TCCARTTGCATGCRGCATYGAGCC | 1b | 2257-2280 | ||

| Second round | CF2 | Sense | *GTACTGAATTCGGTACCGGTTGCTCTTTCTCTATCTTCC | 1a/1b | 851-873 | |

| EAR2 | Antisense | *ACTCGAAGCTTAGATCTTTGATGGTACAAGGRTAATGCC | 1a | 2188-2209 | ||

| EBR2 | Antisense | *ACTCGAAGCTTAGATCTTTGASRGTGCARGGGTAGTGCC | 1b | 2188-2209 | ||

| HVR-1 (496) | RT | RR1 | Antisense | TSCGGAARCARTCMGTGGGGCA | 1a/1b | 2082-2103 |

| First round | CF11 | Sense | CGGCGTGAACTATGCAACAGG | 1a/1b | 821-841 | |

| RR1 | Antisense | TSCGGAARCARTCMGTGGGGCA | 1a/1b | 2082-2103 | ||

| Second round | RAF2 | Sense | *GTACTGAATTCAACTGTTCACCTTCTCTCCCA | 1a | 1207-1227 | |

| 6AR1 | Antisense | *ACTCGAAGCTTTCGGGACAGCCTGAAGAGTTG | 1a | 1682-1702 | ||

| RBF2 | Sense | *GTACTGAATTCAGCTGTTCACCTTCTCGCCTC | 1b | 1207-1227 | ||

| 6BR1 | Antisense | *ACTCGAAGCTTTCYGGGCAYCCGGACGAGTTG | 1b | 1682-1702 | ||

| NS5a (251) | RT | NS5A1aR1 | Antisense | ACGGAGAYCTCCCGCTCRTCC | 1a | 7130-7150 |

| NS5A1bR1 | Antisense | ACGGATAYTTCCCTCTCATCC | 1b | 7130-7150 | ||

| First round | NS5A1aF1 | Sense | CCGTGTTGACGTCCATGCTCA | 1a | 6847-6867 | |

| NS5A1aR1 | Antisense | ACGGAGAYCTCCCGCTCRTCC | 1a | 7130-7150 | ||

| NS5A1bF1 | Sense | CAGTGCTCACTTCCATGCTCA | 1b | 6847-6867 | ||

| NS5A1bR1 | Antisense | ACGGATAYTTCCCTCTCATCC | 1b | 7130-7150 | ||

| Second round | NS5A1aF1 | Sense | *GTACTGAATTCATCCCTCCCATATAACAGCAG | 1a | 6871-6891 | |

| NS5A1aR1 | Antisense | *ACTCGAGATCTACAAG CGGAT CGAAG GAGTCCA | 1a | 7099-7121 | ||

| NS5A1bF1 | Sense | *GTACTGAATTCACCCCTCCCACATTACAGCAG | 1b | 6871-6891 | ||

| NS5A1bR1 | Antisense | *ACTCGAGATCTCGAAGCGGRTCGAAAGAGTCCA | 1b | 7099-7121 |

Primer position is indicated according to the HCV J4 strain (GenBank accession no. D10750). The HCV genotype specificity of primers is indicated. Primers containing restriction sites on their 5′ end are indicated by asterisks. Sizes of PCR products do not include sequences of restriction enzymes. Degenerate bases are matched with standard IUPAC codes.

Cloning and analysis of the NS5A interferon sensitivity region.

RT-PCR was also done to generate a 251-bp fragment encompassing the putative interferon sensitivity-determining region (ISDR) in the NS5A gene. The oligonucleotide primers for generating these fragments are shown in Table 1. Primer numbering is according to HCV J1 strain (GenBank accession no. D10749). The size of the PCR product was 273 bp. The PCR conditions were generally similar to those described for the other fragments, with elongation times restricted to 30 s. PCR fragments were isolated as described below and used directly for sequencing. The length of the sequence used for analysis was 206 bp, which does not include the primer sequences.

Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequencing of PCR fragments.

PCR fragments were isolated by electrophoresis on agarose gels and purified by using Qiagen DNA purification kits. The fragments were ligated into the pTOPO-TA cloning vector (Invitrogen) and Escherichia coli TOP-10 cells were used for transformation and recovery of plasmid clones. Miniprep DNAs were screened for inserts, and clones containing appropriate size inserts were used for nucleotide sequence analysis. Nucleotide sequencing reactions were done by using DTCS Quick Start Reagents (Beckman Coulter) and run on an Applied Biosystems DNA Sequenator.

GenBank accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers of nucleotide sequences analyzed in the present study are AY746598 to AY746942.

Analysis of genetic parameters.

The sequences were aligned with CLUSTAL W (version 1.74) (16). Sequence editing, multiple sequence comparisons were performed with matched programs in the Wisconsin GCG package (Oxford Molecular Group, Inc., version 10.0). The mean genetic distance (d), the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (dS), and the number of nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site (dN) were calculated with the Kimura two-parameter method (all sites) (21) in the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software package (MEGA; version 1.02) (22). Phylogenetic trees were constructed by using the neighbor-joining method (35) with a bootstrap test implanted in MEGA. The genetic complexity at both nucleotide and amino acid level was evaluated for each patient by calculating normalized entropy (Sn) as follows: Sn = S/lnN, where N is the total number of clones, and S = −Σi(pilnpi), where pi is the frequency of each clone in the viral quasispecies population.

Statistical tests.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Base 10.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Ill.). Independent means t tests were used to analyze differences between the genetic parameters of responders and nonresponders at various time points. To determine the relationships between patient characteristics and treatment response, t tests were used to compare age, weight, height, body mass index, inflammation, and fibrosis while Fisher exact tests were used for evaluating gender and race. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was calculated to determine the relationship between genetic heterogeneity and patient age, weight, height, body mass index, inflammation, and fibrosis. Independent means t tests were used to analyze differences between genetic parameters and patient gender and race.

RESULTS

Characterization of the study group.

A total of 29 patients were enrolled in the treatment protocol, 28 of whom completed treatment and follow-up through 24 weeks posttherapy (Table 2). The clinical and demographic characteristics of these patients have been previously reported (29). In brief, patients (17 males and 12 females) ranged in age from 18.6 to 71.3 years. A total of 23 patients were Caucasian, and 6 were African-American. Twenty-five patients had genotype 1a infection, and four had genotype 1b infection. All were treatment naive at the start of therapy. Treatment was initiated by randomization to pegylated alpha-2a interferon (180 μg/week) with or without ribavirin (1,000 to 1,200 mg/day). Subsequently, since combination therapy was recognized to be superior to peginterferon alone, all patients were switched to peginterferon plus ribavirin and treated with this combination for a total of 48 weeks. Thus, some patients received an additional month of peginterferon alone (before initiating combination treatment). Virologic treatment outcomes were determined for three time points: 12 weeks (early viral response [EVR]), 48 weeks (end of treatment response [ETR]), and 72 weeks (sustained viral response [SVR]). For the 12-week time point, response was defined as a >2-log decrease in viral RNA serum, a partial response was defined as a >1- but <2-log decrease in viral RNA, and nonresponse was defined as a <1-log decrease in viral RNA. Outcomes of treatment for the various endpoints are shown in Table 2 for the entire group. The total number of patients with an EVR was 18 of 29. The total number of patients with an ETR was 17 of 29, and the total number with an SVR was 10 of 28. One patient with an EVR did not complete follow-up to the 72-week time point. Of the remaining 17 patients who achieved an ETR, only 10 achieved an SVR. Failure to achieve an EVR occurred in 11 of 29 patients, 9 of whom had a nonresponse, and 2 of whom had a partial response. Failure to achieve an EVR essentially precluded the occurrence of and ETR and SVR in the present study.

TABLE 2.

Treatment outcomes based on virologic responsesa

| Response type | No./total no. of patients examined at:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| wk 12 | wk 48 | wk 72 | |

| CR | 18/29 | 17/29 | 10/28 |

| NR | 9/29 | 12/29 | 18/28 |

| PR | 2/29 | NA | NA |

CR (complete response) = ≥2-log decrease in viral RNA in serum; NR (nonresponse) = <1-log decrease in viral RNA in serum; PR (partial response) = >1- and <2-log decrease in viral RNA in serum. NA, not applicable.

The variation in RNA levels in serum at baseline for the entire group (responders and nonresponders) was in the range of 1.51 × 105 to 1.18 × 107 IU/ml. There was no significant difference between the pretreatment serum virus loads and the treatment outcome for the EVR endpoint (6.4 × 105 copies/ml [nonresponder] versus 4.4 × 105 copies/ml [responder], P = 0.15) or SVR endpoint (data not shown), thus eliminating viral load as a variable which affected treatment responses in this study group. Patterns of decrease in the serum RNA among the responders and nonresponders varied. Patients in the responder group exhibited variable decreases in serum RNA in the early treatment period, with the time to disappearance of viral RNA ranging from 8 to 142 days. Among those achieving an ETR, but not an EVR, the time to disappearance of viral RNA in serum ranged from ca. 16 to 28 weeks.

For other patient variables examined in relationship to treatment response, patient age was significantly lower for early viral responders versus nonresponders (42.9 years versus 51.4 years, respectively; P < 0.05) but not significantly different for sustained viral responders versus nonresponders (45 versus 46.8 years, respectively). For pretreatment liver fibrosis scores, the mean scores were lower for early viral responders versus nonresponders (1.78 versus 2.50, respectively; P < 0.05). The mean scores were also lower for sustained viral responders versus nonresponders (1.73 versus 2.24, respectively), even though this difference was not significant. There was no relationship between treatment responses and either race or genotype (1a versus 1b), respectively.

Phylogeny of pretreatment viral quasispecies.

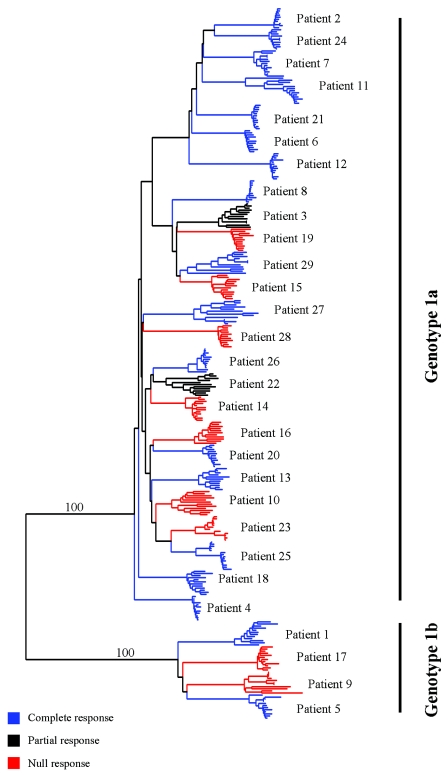

To begin characterization of the genetic variation within and between patient groups as a pretreatment variable, serum RNA was used for RT-PCR to generate 1.36-kb amplicons that encompassed the region from the beginning of E1 to nucleotide position 2280 in the E2 region. Between 10 and 15 individual clones for each patient were sequenced. Evaluation of evolutionary relationships of quasispecies variants within pretreatment serum RNA specimens and analysis for clustering of the evolutionary patterns with respect to treatment outcome were done by constructing a phylogenetic tree for the sequences of the E1-E2 region, as shown in Fig. 1. Each collection of patient-specific quasispecies showed limited genetic evolution at the pretreatment time point. The extent of evolution of the viral populations among different patient samples was also limited. In particular, there was no evidence for a significant difference in evolution between populations from those patients with a complete response to antiviral therapy and those with a nonresponse at the EVR time point. To further screen the E1-E2 region for existence of possible genetic differences that might discriminate responders from nonresponders, a series of trees was constructed based on consensus sequences for each quasispecies population, with consecutive lengths of ca. 150 nucleotides. HVR-1 showed the greatest extent of evolution within a given sample. However, there was no obvious correlation of either HVR-1 or of any region outside of HVR-1 with treatment response (data not shown). This is consistent with the phylogenetic tree shown in Fig. 1. We did not include the putative interferon sensitivity region of E2 (38, 41) in our study for technical reasons which precluded PCR amplification of this portion of E2. Thus, the possible effects of this determinant in influencing treatment responses or in contributing to genetic heterogeneity cannot be evaluated at this time.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of pretreatment viral clones. A neighbor-joining tree was constructed as described in Materials and Methods. The tree depicts evolutionary relationships for responders (blue) and nonresponders (red) or partial responders (black) based on the 12-week endpoint.

HCV genetic parameters at baseline.

To further assess the genetic variation in this patient cohort, complexity and diversity within the E1-E2 region were then analyzed. A summary of the genetic data is shown in Tables 3 and 4, wherein complexity and diversity are analyzed as a function of treatment responses for the 12- and 72-week time points, respectively. Genetic complexity was compared with respect to both nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences for HVR-1. For the subgroup that exhibited no response or only a partial response at 12 weeks, the mean complexity values for nucleotides and amino acids were 0.717 ± 0.037 and 0.627 ± 0.041, respectively. In comparison, the mean values for the group that exhibited a response were 0.563 ± 0.056 and 0.447 ± 0.068, respectively. Although the nonresponder group exhibited greater nucleotide and amino acid complexity than the responder group, only the difference for amino acids was significant (P < 0.05). Genetic diversity was compared between the two treatment response groups separately for the E1, the HVR-1, and the non-HVR-1 regions of E2 (Table 3). For both treatment groups, the mean genetic distances and synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions were highest for the HVR-1 and lowest for the E1 region. For the E1 region, the mean genetic distance for nonresponders was higher than for responders (21.36 versus 13.61, respectively), but the difference was not significant. Synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions in E1 were also more frequent in the nonresponder group, with synonymous substitutions significantly more frequent in nonresponders than responders (P < 0.021). For the HVR-1, mean genetic distances within the nonresponder and responder groups were 121.36 and 81.1 (P = 0.237). Synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions in HVR-1 were also greater for the nonresponder versus the responder group, but the differences were not significant. The mean genetic distance for the remainder of the E2 region was 30.09 for the nonresponder versus 18.44 for the responder group (P < 0.05). Both synonymous and nonsynonymous mutations in this region were significantly greater in the nonresponder than the responder group (P = 0.009 and 0.029, respectively).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of genetic parameters between two groups: early viral response

| Group or P value | No. of patients | Genetic parameter (SD)

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic complexity

|

Genetic diversity (103)

|

||||||||||||

| E1

|

HVR-1

|

E2 without HVR-1

|

|||||||||||

| Nucleotide | Amino acid | d | dS | dN | d | dS | dN | dN/dS | d | dS | dN | ||

| 1 (partial + non) | 11 | 0.717 (0.0369) | 0.627 (0.0415) | 21.364 (2.983) | 52 | 7.818 (1.127) | 121.364 (23.481) | 95.273 (21.467) | 133.818 (25.431) | 1.522 (0.217) | 30.091 (3.967) | 63.364 (9.236) | 21 |

| 2 (complete) | 18 | 0.563 (0.0564) | 0.447 (0.0608) | 13.611 (2.658) | 26 | 6.722 (0.990) | 81.111 (21.647) | 54.278 (16.089) | 96.722 (26.564) | 1.440 (0.345) | 18.444 (3.393) | 35.333 (5.384) | 7 |

| P | 0.059* | 0.043* | 0.071* | 0.021** | 0.484* | 0.237* | 0.134* | 0.356* | 0.865* | 0.038* | 0.009* | 0.029** | |

*, As determined by Student t test; **, as determined by Mann-Whitney rank sum test.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of genetic parameters between two groups: sustained viral response

| Group or P value | No. of patients | Genetic parameter (SD)

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic complexity

|

Genetic Diversity (103)

|

||||||||||||

| E1

|

HVR-1

|

E2 without HVR-1

|

|||||||||||

| Nucleotide | Amino acid | d | dS | dN | d | dS | dN | dN/dS | d | dS | dN | ||

| 1 (partial + non) | 11 | 0.665 (0.0426) | 0.548 (0.0457) | 17.333 (2.229) | 44.611 (6.979) | 6.5 | 103.667 (18.458) | 66 | 114.722 (20.838) | 1.36 | 24.056 (3.130) | 51.778 (6.885) | 9.5 |

| 2 (complete) | 18 | 0.551 (0.0762) | 0.460 (0.0879) | 15.273 (4.161) | 35.273 (11.260) | 5.0 | 84.455 (31.382) | 17 | 104.364 (38.478) | 1.23 | 20.909 (5.321) | 36.455 (8.261) | 8.0 |

| P | 0.167 | 0.333 | 0.641 | 0.462 | 0.893 | 0.576 | 0.045 | 0.798 | 0.770 | 0.589 | 0.172 | 0.653 | |

The same baseline genetic parameters were compared for the treatment outcome groups with respect to sustained viral responses (Table 4). In this case, the genetic complexities were higher for the nonresponder than for the responder group, but the differences were not significant. For genetic distance parameters, there was again a hierarchy of values in both treatment groups in the following order: HVR-1 > non-HVR-1 E2 > E1. All values in these groups were greater for nonresponders than for responders, although the differences were not significant, with the exception of the number of synonymous substitutions in the HVR-1 (P = 0.045). Taken together, the data from these analyses indicate that a greater pretreatment level of amino acid complexity in the HVR-1 region and a greater nucleotide and amino acid diversity in the E2 region outside of HVR-1 are significantly associated with a higher likelihood of nonresponse at the early viral response time point in this patient population. However, these baseline parameters do not distinguish responders from nonresponders with regard to achievement of a sustained viral response, even though a trend toward higher genetic complexity and diversity occurred among nonresponders.

Pretreatment viral genetic parameters were also compared to determine whether the subgroup of seven patients who exhibited an EVR and ETR but later relapsed and failed to achieve an SVR (EVR “escapers”) could be distinguished from the other EVRs. As shown in Table 5, there were no significant differences in the nucleotide and amino acid complexities of HVR-1 or in the diversity of the E1 and non-HVR-1 regions of E2 between these two groups of early viral responders.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of genetic parameters between EVR escape and nonescape groups

| Group or P value | No. of patients | Genetic parameter (SD)

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic complexity

|

Genetic diversity (103)

|

||||||||||||

| E1

|

HVR-1

|

E2 without HVR-1

|

|||||||||||

| Nucleotide | Amino acid | d | dS | dN | d | dS | dN | dN/dS | d | dS | dN | ||

| 1 (nonescape) | 11 | 0.551 (0.1387) | 0.460 (0.1601) | 15.273 (7.5772) | 35.273 (20.506) | 7.6364 (2.7375) | 84.455 (57.152) | 50.182 (44.629) | 104.36 (70.075) | 1.5855 (0.9709) | 20.909 (9.691) | 36.455 (15.044) | 20.182 (14.342) |

| 2 (escape) | 7 | 0.583 (0.144) | 0.425 (0.132) | 11 (3.3673) | 26.714 (10.353) | 5.2857 (1.3145) | 75.857 (46.784) | 60.714 (28.253) | 84.714 (56.913) | 1.2114 (0.5411) | 14.571 (6.2678) | 33.571 (9.1454) | 6.5714 (1.9067) |

| P | 0.787 | 0.792 | 0.45 | 0.579 | 0.259 | 0.853 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.613 | 0.378 | 0.237 | 0.193 | |

Genetic heterogeneity parameters were also examined in relationship to pretreatment liver fibrosis scores based on the observation that these scores were lower in the case of both early and sustained viral responders compared to nonresponders, as mentioned above. The correlations between fibrosis scores and nucleotide and amino acid complexities of the HVR-1 were consistently stronger for patients who did not achieve an EVR or SVR compared to those who did and for patients who escaped from an EVR versus those who did not (data not shown). In no case, however, were these correlations statistically significant relationships. Similar but less strong trends were observed between fibrosis scores and genetic distance parameters among the same treatment response groups, although again no significant correlations could be established.

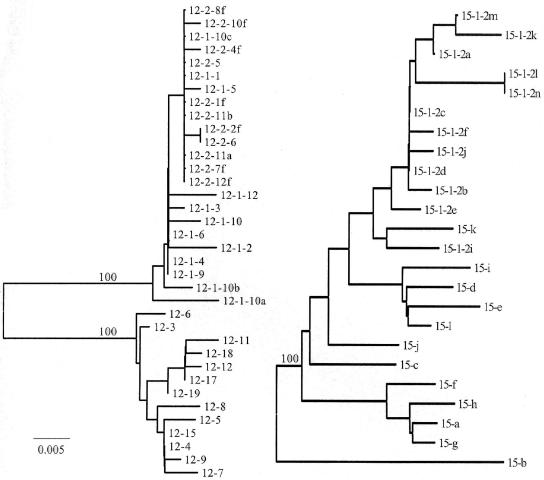

Genetic parameters during treatment in patients with different therapeutic responses.

To determine whether differences evolved in quasispecies complexity and diversity between early viral responders and nonresponders while they received antiviral therapy, several patients from these two respective groups were selected for further analysis. Quasispecies characterization was done on serial RNA samples for three nonresponders and four responders (based on the 12-week time point). A region of 494 nucleotides encompassing the HVR-1, part of E1 and part of E2 outside of HVR-1 was chosen for analysis, because the baseline genetic distance parameters were greatest for HVR-1 in both treatment groups, and this region was therefore expected to be most sensitive to evolutionary changes in response to antiviral therapy. The results of this analysis are shown in Table 6. For the nonresponder group (patients 14, 15, and 16), there was no significant change in the viral RNA load in serum from baseline to the time that the subsequent samples were collected between 90 and 270 days after initiation of therapy. The mean nucleotide complexities for this group at baseline versus the final follow-up sample were 0.737 and 0.604, respectively. The mean amino acid complexities for these same samples were 0.692 and 0.331, respectively. The mean diversities at baseline and follow-up ranged from 0.063 to 0.114 and 0.01 to 0.131, respectively. Comparison of the diversities of baseline and follow-up samples for these patients showed either no marked change (patient 14) or a decrease (patients 15 and 16) with similar trends for both synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Comparison of the genetic diversity of the baseline samples alone versus the composite of baseline plus follow-up samples revealed either no change (patient 15 [0.063 versus 0.063]) or a slight increase in genetic distance (patients 14 [0.110 versus 138] and 16 [0.114 versus 0.177]). Quasispecies evolution was analyzed for one patient (patient 15 [see below and Fig. 2 ]), which revealed a monophyletic pattern of variants, a finding consistent with the lack of significant genetic diversity in this interferon-resistant population. In each of the individual nonresponders, several quasispecies variants were present at baseline and showed different patterns of change (data not shown). In one case these were replaced by several new quasispecies, none of which was dominant (patient 14); in another case, one subdominant clone present at baseline became dominant at follow-up (patient 15); in the third case, a dominant quasispecies was present at follow-up but was not present at baseline or day 90 (patient 16). Genetic diversity increased in one of the three cases (patient 14) between baseline and follow-up, and the dN/dS ratio increased in only this case as well.

TABLE 6.

HVR-1 genetic parameters on treatment in patients with different therapeutic responses

| Sample | Genotype | Daya | RNA | No. | Complexity

|

Intersample analysisb (SD)

|

Intrasample analysisc

|

Responsed

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide | Amino acid | d | dS | dN | dN/dS | d | dS | dN | dN/dS | EVR | SVR | |||||

| LIV14 | 1a | −30 | 3.79E+05 | 12 | 0.697 | 0.635 | 0.110 (0.027) | 0.043 (0.027) | 0.141 (0.033) | 3.28 | 0.110 | 0.043 | 0.141 | 3.28 | N | N |

| 150 | 4.76E+05 | 13 | 0.693 | 0.693 | 0.131 (0.029) | 0.026 (0.017) | 0.177 (0.046) | 6.81 | 0.138 | 0.039 | 0.181 | 4.64 | ||||

| LIV15 | 1a | −30 | 4.16E+05 | 12 | 0.779 | 0.703 | 0.063 (0.017) | 0.044 (0.020) | 0.071 (0.023) | 1.61 | 0.063 | 0.044 | 0.071 | 1.61 | N | N |

| 150 | 2.50E+05 | 12 | 0.450 | 0.000 | 0.010 (0.006) | 0.043 (0.026) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.00 | 0.063 | 0.142 | 0.040 | 0.28 | ||||

| LIV16 | 1a | −30 | 3.67E+05 | 11 | 0.737 | 0.737 | 0.114 (0.024) | 0.087 (0.034) | 0.126 (0.034) | 1.45 | 0.114 | 0.087 | 0.126 | 1.45 | N | N |

| 90 | 5.70E+05 | 14 | 0.376 | 0.376 | 0.027 (0.011) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.037 (0.016) | NAe | 0.095 | 0.057 | 0.109 | 1.91 | ||||

| 270 | 5.57E+05 | 12 | 0.668 | 0.331 | 0.033 (0.013) | 0.054 (0.027) | 0.026 (0.014) | 0.48 | 0.177 | 0.213 | 0.165 | 0.77 | ||||

| LIV18 | 1a | −30 | 3.72E+05 | 12 | 0.796 | 0.607 | 0.076 (0.021) | 0.078 (0.041) | 0.075 (0.027) | 0.96 | 0.076 | 0.078 | 0.075 | 0.96 | C | N |

| 29 | 3.30E+04 | 10 | 0.473 | 0.473 | 0.133 (0.031) | 0.150 (0.058) | 0.128 (0.042) | 0.85 | 0.129 | 0.153 | 0.123 | 0.80 | ||||

| 60 | 3.34E+02 | 12 | 0.432 | 0.432 | 0.123 (0.032) | 0.175 (0.082) | 0.106 (0.028) | 0.61 | 0.163 | 0.256 | 0.135 | 0.53 | ||||

| LIV04 | 1a | −30 | 5.70E+05 | 12 | 0.115 | 0.115 | 0.004 (0.003) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.006 (0.004) | NA | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.006 | NA | C | C |

| 15 | 1.38E+03 | 13 | 0.917 | 0.761 | 0.050 (0.016) | 0.033 (0.019) | 0.058 (0.020) | 1.76 | 0.035 | 0.017 | 0.043 | 2.53 | ||||

| LIV12 | 1a | −30 | 2.44E+05 | 13 | 0.592 | 0.592 | 0.018 (0.008) | 0.007 (0.007) | 0.023 (0.012) | 3.29 | 0.018 | 0.007 | 0.023 | 3.29 | C | C |

| 1 | 2.50E+04 | 12 | 0.442 | 0.115 | 0.010 (0.005) | 0.025 (0.014) | 0.006 (0.004) | 0.24 | 0.228 | 0.065 | 0.296 | 4.55 | ||||

| 7 | 1.49E+02 | 11 | 0.127 | 0.127 | 0.002 (0.002) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.003 (0.003) | NA | 0.225 | 0.053 | 0.298 | 5.63 | ||||

| LIV02 | 1a | −30 | 1.40E+05 | 10 | 0.141 | 0.000 | 0.002 (0.003) | 0.011 (0.012) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.00 | 0.002 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.00 | C | N |

| 3 | 3.62E+04 | 13 | 0.308 | 0.308 | 0.147 (0.032) | 0.061 (0.045) | 0.181 (0.060) | 2.97 | 0.094 | 0.045 | 0.113 | 2.51 | ||||

| 29 | 8.46E+02 | 13 | 0.309 | 0.209 | 0.007 (0.005) | 0.014 (0.017) | 0.005 (0.004) | 0.36 | 0.356 | 0.166 | 0.430 | 2.59 | ||||

Day indicates treatment day when the serum sample for RNA load and quasispecies testing was drawn.

Values for individual baseline and follow-up samples.

Values for composite of baseline and follow-up samples.

C, a response was achieved; N, a response was not achieved.

NA, not applicable.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic trees for baseline and follow-up sequences of the HVR-1 for representative patients within the early viral responder and nonresponder subgroups. Trees were constructed with the neighbor-joining method, and the reliability of tree topology confirmed with 100 bootstrap replicates at the major branch points. The left panel shows the tree for responder patient 12 (baseline samples are indicated by 12-3, 12-6, 12-9, etc.; follow-up samples are indicated by 12-1-4, 12-1-9, etc., and 12-2-6, 12-2-10f, etc. [see Table 5]). The right panel shows the tree for nonresponder patient 15 (baseline and follow-up samples are indicated as described for patient 12).

Among the responding patients selected for further study, samples were obtained when serum RNA had fallen by 2 to 3 logs (patients 2, 4, 12, and 18). The mean nucleotide complexities for this group at baseline and final follow-up were 0.411 and 0.446, respectively. The mean amino acid complexities at baseline and follow-up were 0.329 and 0.382, respectively. Comparison of genetic diversity of baseline samples versus that of the composite of baseline and follow-up samples revealed increases in all four cases (patient 18 [0.076 versus 0.163], patient 4 [0.004 versus 0.035], patient 12 [0.018 versus 0.225], and patient 2 [0.002 versus 0.356]). One patient (patient 12) was analyzed for quasispecies evolution, which revealed two distinct lineages (see below and Fig. 2), which is consistent with the findings described above. The responder patients exhibited two patterns in terms of amino acid complexities during the period when RNA levels were falling (data not shown). In three cases (patients 2, 12, and 18) either a dominant quasispecies or several subdominant variants were present at baseline, and these were replaced by a new dominant variant. In another case (patient 4) a dominant variant was present at baseline but became only a minor variant, and no quasispecies was dominant. The increased genetic distance in the responder subgroup involved both synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions, with the dN/dS ratio increasing in three of the four cases, suggesting an increase in amino acid diversity during response to treatment over a period of up to 29 days, during which PCR products were recoverable from the serum (patients 4, 12, and 2). Comparison of changes in diversity between baseline and follow-up samples for responders and nonresponder groups revealed an overall greater increase in diversity over time in the former group compared to the latter.

Phylogenetic trees for representative patients in the responder and nonresponder groups are shown in Fig. 2. Responding patient 12 exhibited two distinct evolutionary clusters when baseline and follow-up samples were compared. One was composed of baseline variants, and the other was composed of variants appearing on days 1 and 7, which showed intermingling of variants (Fig. 2, left). This patient went on to achieve a sustained viral response. Nonresponding patient 15 showed little evolution among quasispecies variants when baseline and follow-up samples were compared (Fig. 2, right), with intermingling of viruses from the baseline and subsequent time points. This suggests a relative evolutionary stasis of the quasispecies population in response to interferon compared to the pattern observed for patient 12.

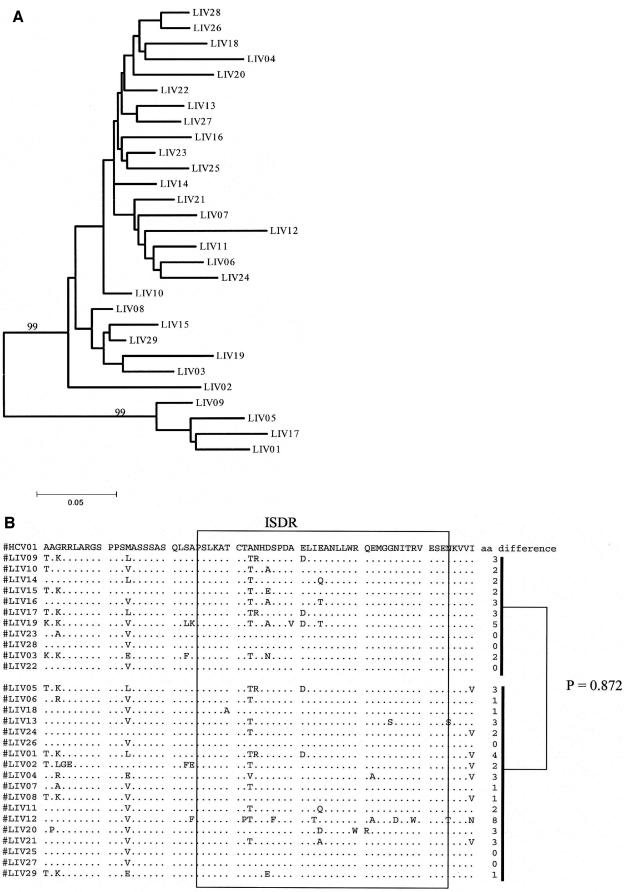

Analysis of NS5A sequence heterogeneity.

To determine whether there was a relationship between early viral response and genetic determinants within the NS5A region, pretreatment serum RNAs were used for derivation of a 251-bp PCR product that encompassed the ISDR, and nucleotides 6892 to 7098 were then used for comparison of the population sequences among patients. A phylogenetic tree constructed for these consensus sequences showed a very similar amount of evolutionary drift for this region when responders and nonresponders were compared based on the 12-week time point (Fig. 3A), suggesting there was no overall dramatic difference in sequence heterogeneity between these two groups. To further analyze the relationship of these two groups, the sequences from the responders and nonresponders were compared for differences in nucleotide and amino acid substitutions. Within the ISDR, the mean and range of amino acid substitutions for nonresponders were 2 and 0 to 5, respectively, whereas among responders quasispecies diversity was greater (mean of 2.1 substitutions, [range, 0 to 8]). Responders also exhibited substitutions at more codon positions than nonresponders (16 versus 6, respectively). Both groups exhibited some common substitutions (alanine to threonine at codon 2217, asparagine to arginine at codon 2218, and glutamic acid to aspartic acid at codon 2225). Comparison of each collection of NS5A sequences was made relative to a reference consensus sequence, derived from a set of available genotype 1a isolates as described in Materials and Methods. The number of amino acid differences between the ISDR regions of responders and the reference sequence, as well as the number of amino acid differences between the nonresponders and the reference sequence, showed no significant differences (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that the pretreatment sequences of the NS5A ISDR do not correlate with the response to pegylated interferon.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of NS5A sequences and relationship to treatment response. (A) Phylogenetic relationship of population sequences for the 206 nucleotide sequence from baseline serum samples of all 29 patients in the study, together with HCV01 (HCV genotype 1a prototype [M62321]). (B) Genetic comparison of NS5A sequences for nonresponders (top) and responders (bottom) with respect to the 1a prototype sequence. The reference sequence is indicated on the top line. The P value refers to the comparison of genetic distances of responders and HCV01 versus nonresponders and HCV01.

DISCUSSION

In the cohort of patients included in this study, we attempted to represent patients with well-established chronic HCV infection who had not undergone any prior treatment with interferon and had substantial viral loads based on viral RNA levels in serum. In this group, combination therapy with pegylated alpha interferon and ribavirin resulted in an early viral response rate of 62%, an end of treatment response rate of 55%, and a sustained viral response rate of ca. 38%. Overall, the percentage of sustained viral responses is lower than the results of larger studies of pegylated alpha-2a interferon, upon which the NIH consensus for antiviral therapy is based. In these studies, SVR rates of 46 to 51% and an EVR of up to 85% were reported for patients with genotype 1 infection receiving comparable doses of peginterferon and ribavirin as the patients in our study (10, 14). The lower rates observed in the study reported here may result from the small numbers of patients under analysis. However, the results are generally representative of those of the larger studies, and thus we believe serve as a suitable group for analysis of genetic parameters in relationship to this form of antiviral therapy with long-acting interferon.

RNA loads in response to treatment showed differences in the kinetics of decline among both responders and nonresponders, indicating heterogeneity in the pattern of response to this form of antiviral therapy, although pretreatment RNA levels in serum were not predictive of treatment responses. Age and liver fibrosis were related to early viral response, since responders were significantly younger and exhibited significantly lower fibrosis scores than nonresponders. Age was not a distinguishing factor for sustained viral responders versus nonresponders, although liver fibrosis scores were again lower among the responders. Taken together, these data indicate a more favorable treatment response in the context of less severe pretreatment liver fibrosis. The relationship of fibrosis to viral genetic parameters is discussed further below.

In terms of the hypothesis that the degree of genetic variation of HCV is a factor which affects the response to treatment, we observed a relationship between genetic complexity at both the nucleotide and the amino acid level of HVR-1 and the virologic outcome after 12 weeks of antiviral therapy. The nucleotide complexity was lower in the responder group, and the amino acid complexity for this region was significantly lower. Analysis of the genetic diversity with respect to the 12-week treatment outcome also showed differences between responders and nonresponders. For the E1 region, a lower nucleotide diversity was apparent among the responders and was associated with a lower rate of synonymous but not nonsynonymous substitutions. For E2, the genetic diversity and number of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions were all lower among responders than nonresponders, but the differences were significant for the non-HVR-1 region of E2 but not that of HVR-1. These differences were associated with a lower rate of both synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions. The data for the E1 region suggest that although there is greater evolution of this region among nonresponders than responders, this does not seem to be driven by immune pressure, since the amino acid diversity was not greater in conjunction with this differences in nucleotide complexity. This may reflect that the E1 protein is less involved in immune selection than E2. For the HVR-1, the greater genetic distances among nonresponders also suggest greater evolution of viruses in the latter group. The lack of a significant difference compared to responders suggests that in the cohort of patients studied here, the HVR-1 is highly evolved as a result of chronic infection and immune pressure and is not a particularly sensitive indicator of whether a response will occur at the 12-week time point. The region of E2 outside of HVR-1 exhibited the greatest differences in genetic distances between responders and nonresponders. This suggests that, like HVR-1, the non-HVR-1 region of the E2 protein may also be subject to immune pressure, with a greater degree of baseline genetic distance in it being a factor involved in poor treatment outcome at the 12-week time point. At the present time, we cannot distinguish whether the differences in non-HVR-1 regions of E2 are simply markers for viral variation that are related to poor treatment response through other mechanisms unrelated to the E2 region. Specific regions of E2 might be involved in the genetic diversity differences between responders and nonresponders and reflect differences in amino acid complexity between these two groups, resulting from immune selection on E2 outside of the HVR-1. This could, for instance, involve HVR-2, where sequence heterogeneity has been observed (34). It is also not known whether the putative interferon-sensitive region of E2 (38, 41) could also contribute any effect, since that region was not included in our analysis.

Pretreatment fibrosis score appeared to be a predictor of antiviral response, at least for early viral responders, although its relationship to viral genetic parameters needs to be further investigated, since higher fibrosis scores and increased genetic heterogeneity of the E1-E2 region were related as trends, but no significant correlations could actually be shown. Although subjects with an early viral response were younger and exhibited lower fibrosis scores than those without a response, these characteristics did not therefore clearly explain the predictive value of the viral genetic complexity of the HVR-1 for this response. A possible relationship could have been obscured by the relatively small numbers of subjects examined in the present study or, alternatively, the lack of a large enough range in the fibrosis scores to demonstrate such an effect. Thus, our data do not allow a conclusion that lesser fibrosis, as might be observed in younger patients with a shorter duration of infection, was necessarily driven by a lower degree of viral genetic heterogeneity.

In contrast to these findings for the early viral response, there was no significant correlation between sustained viral response and genetic complexity and diversity for the E1-E2 region, although the HVR-1 showed substantial differences for these two groups in genetic distance parameters compared to either E1 or the non-HVR-1 region of E2. This phenomenon is likely explained by the fact that there was crossover of some patients who had an early viral response into the group that did not have a sustained viral response (7 of the 18 early viral responders, Table 2). We interpret this to mean that viral parameters are determinants of the early response to pegylated interferon-ribavirin therapy, with less viral quasispecies complexity and diversity favoring a treatment response. However, these parameters appear to be less important as determinants of response over the remaining treatment period. Presumably, host factors such as T-cell effector functions and virus-specific antibodies presumably operate to control and eliminate HCV variants that are becoming resistant to interferon over time. Failure of these adaptive defenses may be related to mutations that render viral variants able to escape from cytotoxic T cells and neutralizing antibodies. This could contribute to the inability to maintain a virologic response between 12 and 72 weeks and may be involved in the nonresponding patients studied here, since the crossovers into the nonresponse group occurred after the end-of-treatment time point. We must, however, acknowledge that there are other interpretations of these data as well.

Our data are generally consistent with some other studies that have examined genetic parameters as predictors of response to antiviral therapy. Among patients with genotype 1b infection treated with either peginterferon or alpha interferon in combination with ribavirin, pretreatment viral genetic heterogeneity, as indicated by nucleotide complexity of the HVR-1, was lower in those exhibiting a short-term response to therapy (6 months of treatment), but this was not predictive of a sustained viral response (1, 2). In a group of patients of genotypes 1, 2, or 3 for whom genetic complexity and diversity were analyzed in relationship to interferon monotherapy, the pretreatment genetic complexity and diversity of a 558-nucleotide region encompassing the HVR-1 did not correlate with achieving a sustained response (9). However, decreases in these parameters during the initial few weeks of therapy occurred in the group of patients who ultimately achieved a sustained response. The rate of early viral responses were not reported in that study, and only a small number of responding patients were in the genotype 1 category. Similar conclusions about the relationship of pretreatment genetic parameters to sustained viral response were observed in another study (36), where immune pressure, reflected by a high ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitutions in HVR-1, was observed in the context of virus eradication. This suggests that host rather than viral factors are more important in this process. Other studies have also reported changes in viral quasispecies complexity and diversity in response to interferon therapy, and it is apparent that some patients appear to exhibit viral evolution, whereas others do not, when HVR-1 is used as an indicator (32). The factors responsible for this variation are not known, and these may be responsible in part for conflicting data obtained in small studies of HCV genetic variation and treatment outcomes, where nucleotide sequence analysis and/or SSCP have been used for analysis of genetic diversity (13, 15, 17, 19, 31, 42, 44).

We also conducted analysis of genetic parameters on a subset of responders and nonresponders using serum samples obtained while on treatment. This included patients who exhibited virus reduction on the order of 3 logs over a period of 7 to 60 days. The HVR-1 region was selected for this analysis because this region is presumed to undergo immune selection during the course of chronic infection, and published data support the hypothesis that this region exhibits a decrease in the genetic complexity and diversity in response to interferon therapy (9). There was no significant decrease in the viral RNA load among the nonresponders chosen in our analysis. The overall trend among nonresponders was a slight decrease in quasispecies complexity and diversity with time, which is consistent with the preservation of interferon-resistant virus clones, although there is no formal proof of this based on our available data. Among responders there was either a slight increase or decrease in quasispecies complexity over time, accompanied by increases or decreases in genetic distance parameters, respectively. This contrasts with the finding that quasispecies diversity uniformly decreases among interferon-responsive patients (9) and suggests that genotype 1 infections may in fact exhibit more varied patterns of quasispecies evolution during successful short-term eradication of viral infection, although it is conceivable that this difference is also related to an effect of long-acting interferon in driving viral evolution. Although another study of quasispecies viral evolution during peginterferon plus ribavirin therapy has shown a decline in genetic complexity and diversity of HVR-1 among responding patients (2), some of the subjects in that study exhibited an increase in these parameters despite a decline in viral RNA levels in serum, a result similar to the phenomenon we observed. Further evaluation of larger numbers of treatment responders is needed to ascertain the basis for the variable response in quasispecies evolution while on antiviral therapy.

The NS5A region contains a putative interferon sensitivity determinant that has been the subject of numerous investigations which have generated conflicting data on the relationship of genetic variations in this region to responsiveness to interferon (5, 6, 12, 20, 25, 26, 30, 33, 37, 40, 48). We did not observe that the NS5A ISDR region contained any genetic markers that allowed a distinction of responders from nonresponders. This issue has remained controversial since the original report of sequence heterogeneity within the ISDR correlating with response to interferon and subsequent studies that failed to substantiate this observation. We also did not examine regions flanking the ISDR that have been implicated in binding to PKR (11) and thus cannot exclude the possibility that determinants in such regions could play a role in modulating the response to pegylated interferon in the patient population studied here.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the NIH (DK-98017 and DK-04917) and by support from Roche Laboratories.

We are grateful to Janice Strinko for managing the clinical protocol.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbate, I., G. Cappiello, O. Lo Iacono, R. Longo, D. Ferraro, G. Antonucci, V. Di Marco, R. Di Stefano, A. Craxi, M. C. Solmone, A. Spano, G. Ippolito, and M. R. Capobianchi. 2003. Heterogeneity of HVR-1 quasispecies is predictive of early but not sustained virological response in genotype 1b-infected patients undergoing combined treatment with PEG- or STD-IFN plus RBV. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 17:162-165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbate, I., O. Lo Iacono, R. Di Stefano, G. Cappiello, E. Girardi, R. Longo, D. Ferraro, G. Antonucci, V. Di Marco, M. Solmone, A. Craxi, G. Ippolito, and M. R. Capobianchi. 2004. HVR-1 quasispecies modifications occur early and are correlated to initial but not sustained response in HCV-infected patients treated with pegylated- or standard-interferon and ribavirin. J. Hepatol. 40:831-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alter, M. J., D. Kruszon-Moran, O. V. Nainan, G. M. McQuillan, F. Gao, L. A. Moyer, R. A. Kaslow, and H. S. Margolis. 1999. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:556-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, R. S., Jr., and P. J. Gaglio. 2003. Scope of worldwide hepatitis C problem. Liver Transpl. 11:S10-S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chayama, K., A. Tsubota, M. Kobayashi, K. Okamoto, M. Hashimoto, Y. Miyano, H. Koike, M. Kobayashi, I. Koida, Y. Arase, S. Saitoh, Y. Suzuki, N. Murashima, K. Ikeda, and H. Kumada. 1997. Pretreatment virus load and multiple amino acid substitutions in the interferon sensitivity-determining region predict the outcome of interferon treatment in patients with chronic genotype 1b hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 25:745-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enomoto, N., I. Sakuma, Y. Asahina, M. Kurosaki, T. Murakami, C. Yamamoto, Y. Ogura, N. Izumi, F. Marumo, and C. Sato. 1996. Mutations in the nonstructural protein 5A gene and response to interferon in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus 1b infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 334:77-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan, X., H. Solomon, J. E. Poulos, B. A. Neuschwander-Tetri, and A. M. Di Bisceglie. 1999. Comparison of genetic heterogeneity of hepatitis C viral RNA in liver tissue and serum. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 94:1347-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farci, P., A. Shimoda, A. Coiana, G. Diaz, G. Peddis, J. C. Melpolder, A. Strazzera, D. Y. Chien, S. J. Munoz, A. Balestrieri, R. H. Purcell, and H. J. Alter. 2000. The outcome of acute hepatitis C predicted by the evolution of the viral quasispecies. Science 288:339-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farci, P., R. Strazerra, H. J. Alter, S. Farci, D. Degloannis, A. Colana, G. Peddis, F. Usai, G. Serra, L. Chessa, G. Diaz, A. Balestrieri, and R. H. Purcell. 2002. Early changes in hepatitis C viral quasispecies during interferon therapy predict the therapeutic outcome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3081-3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fried, M. W., M. L. Shiffman, K. R. Reddy, C. Smith, G. Marinos, F. L. Goncales, Jr., D. Haussinger, M. Diago, G. Carosi, D. Dhumeaux, A. Craxi, A. Lin, J. Hoffman, and J. Yu. 2002. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:975-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gale, M., Jr., C. M. Blakely, B. Kwieciszewski, S. L. Tan, M. Dossett, N. M. Tang, M. J. Korth, S. J. Polyak, D. R. Gretch, and M. G. Katze. 1998. Control of PKR protein kinase by hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A protein: molecular mechanisms of kinase regulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:5208-5218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerotto, M., F. Dal Pero, D. G. Sullivan, L. Chemello, L. Cavalletto, S. J. Polyak, P. Pontisso, D. R. Gretch, and A. Alberti. 1999. Evidence for sequence selection within the nonstructural 5A gene of hepatitis C virus type 1b during unsuccessful treatment with interferon-alpha. J. Viral Hepat. 6:367-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez-Peralta, R. P., K. Qian, J. Y. She, G. L. Davis, T. Ohno, M. Mizokami, and J. Y. Lau. 1996. Clinical implications of viral quasispecies heterogeneity in chronic hepatitis C. J. Med. Virol. 49:242-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hadziyannis, S. J., H. Sette, Jr., T. R. Morgan, V. Balan, M. Diago, P. Marcellin, G. Ramadori, H. Bodenheimer, Jr., D. Bernstein, M. Rizzetto, S. Zeuzem, P. J. Pockros, A. Lin, A. M. Ackrill, and the PEGASYS International Study Group. 2004. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann. Intern. Med. 140:346-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassoba, H. M., N. Bzowej, M. Berenguer, M. Kim, S. Zhou, Y. Phung, R. Grant, M. G. Pessoa, and T. L. Wright. 1999. Evolution of viral quasispecies in interferon-treated patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J. Hepatol. 31:618-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins, D. G., and P. M. Sharp. 1988. CLUSTAL: a package for performing multiple sequence alignment on a microcomputer. Gene 73:237-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hino, K., Y. Yamaguchi, D. Fujiwara, Y. Katoh, M. Korenaga, M. Okazaki, M. Okuda, and K. Okita. 2000. Hepatitis C virus quasispecies and response to interferon therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C: a prospective study. J. Viral Hepat. 7:36-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honda, M., S. Kaneko, A. Sakai, M. Unoura, S. Murakami, and K. Kobayashi. 1994. Degree of diversity of hepatitis C virus quasispecies and progression of liver disease. Hepatology 20:1144-1151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanazawa, Y., N. Hayashi, E. Mita, T. Li, H. Hagiwara, A. Kasahara, H. Fusamoto, and T. Kamada. 1994. Influence of viral quasispecies on effectiveness of interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis C patients. Hepatology 20:1121-1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khorsi, H., S. Castelain, A. Wyseur, J. Izopet, V. Canva, A. Rombout, D. Capron, J. P. Capron, F. Lunel, L. Stuyver, and G. Duverlie. 1997. Mutations of hepatitis C virus 1b NS5A 2209-2248 amino acid sequence do not predict the response to recombinant interferon-alfa therapy in French patients. J. Hepatol. 27:72-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura, M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimura, S., K. Tamura, and M. Nei. 1993. MEGA: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis, version 1.0. Pennsylvania State University, Philadelphia.

- 23.Koizumi, K., N. Enomoto, M. Kurosaki, T. Murakami, N. Izumi, F. Marumo, and C. Sato. 1995. Diversity of quasispecies in various disease stages of chronic hepatitis C virus infection and its significance in interferon treatment. Hepatology 22:30-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwok, S., and R. Higuchi. 1989. Avoiding false positives with PCR. Nature 339:327-328. (Erratum, 339:490.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurosaki, M., N. Enomoto, T. Murakami, I. Sakuma, Y. Asahina, C. Yamamoto, T. Ikeda, S. Tozuka, N. Izumi, F. Marumo, and C. Sato. 1997. Analysis of genotypes and amino acid residues 2209 to 2248 of the NS5A region of hepatitis C virus in relation to the response to interferon-beta therapy. Hepatology 25:750-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mangoni, E. D., D. M. Forton, G. Ruggiero, and P. Karayiannis. 2003. Hepatitis C virus E2 and NS5A region variability during sequential treatment with two interferon-alpha preparations. J. Med. Virol. 70:62-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naito, M., N. Hayashi, T. Moribe, E. H. Hagiwara, Mita, Y. Kanazawa, A. Kasahara, H. Fusamoto, and T. Kamada. 1995. Hepatitis C viral quasispecies in hepatitis C virus carriers with normal liver enzymes and patients with type C chronic liver disease. Hepatology 22:407-412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neumann, A. U., N. P. Lam, H. Dahari, D. R. Gretch, T. E. Wiley, T. J. Layden, and A. S. Perelson. 1998. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science 282:103-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ni, J., E. Hembrador, A. M. Di Bisceglie, I. M. Jacobson, A. H. Talal, D. Butera, C. M. Rice, T. J. Chambers, and L. B. Dustin. 2003. Accumulation of B lymphocytes with a naive, resting phenotype in a subset of hepatitis C patients. J. Immunol. 170:3429-3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pawlotsky, J. M., G. Germanidis, A. U. Neumann, M. Pellerin, P. O. Frainais, and D. Dhumeaux. 1998. Interferon resistance of hepatitis C virus genotype 1b: relationship to nonstructural 5A gene quasispecies mutations. J. Virol. 72:2795-2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pawlotsky, J. M., M. Pellerin, M. Bouvier, F. Roudot-Thoraval, G. Germanidis, A. Bastie, F. Darthuy, J. Remire, C. J. Soussy, and D. Dhumeaux. 1998. Genetic complexity of the hypervariable region 1 (HVR1) of hepatitis C virus (HCV): influence on the characteristics of the infection and responses to interferon alfa therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J. Med. Virol. 54:256-264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pawlotsky, J. M., G. Germanidis, P. O. Frainais, M. Bouvier, A. Soulier, M. Pellerin, and D. Dhumeaux. 1999. Evolution of the hepatitis C virus second envelope protein hypervariable region in chronically infected patients receiving alpha interferon therapy. J. Virol. 73:6490-6499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polyak, S. J., S. McArdle, S. L. Liu, D. G. Sullivan, M. Chung, W. T. Hofgartner, R. L. Carithers, Jr., B. J. McMahon, J. I. Mullins, L. Corey, and D. R. Gretch. 1998. Evolution of hepatitis C virus quasispecies in hypervariable region 1 and the putative interferon sensitivity-determining region during interferon therapy and natural infection. J. Virol. 72:4288-4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roggendorf, M., M. Lu, K. Fuchs, G. Ernst, M. Hohne, and E. Schreier. 1993. Variability of the envelope regions of HCV in European isolates and its significance for diagnostic tools. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 7:27-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandres, K., M. Dubois, C. Pasquier, J. L. Payen, L. Alric, M. Duffaut, J. P. Vinel, J. P. Pascal, J. Puel, and J. Izopet. 2000. Genetic heterogeneity of hypervariable region 1 of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) genome and sensitivity of HCV to alpha interferon therapy. J. Virol. 74:661-668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarrazin, C., T. Berg, J. H. Lee, B. Ruster, B. Kronenberger, W. K. Roth, and S. Zeuzem. 2000. Mutations in the protein kinase-binding domain of the NS5A protein in patients infected with hepatitis C virus type 1a are associated with treatment response. J. Infect. Dis. 181:432-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarrazin, C., M. Bruckner, E. Herrmann, B. Ruster, K. Bruch, W. K. Roth, and S. Zeuzem. 2001. Quasispecies heterogeneity of the carboxy-terminal part of the E2 gene including the PePHD and sensitivity of hepatitis C virus 1b isolates to antiviral therapy. Virology 289:150-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scheuer, P. J., R. A. Standish, and A. P. Dhillon. 2002. Scoring of chronic hepatitis. Clin. Liver Dis. 6:335-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Squadrito, G., F. Leone, M. Sartori, B. Nalpas, P. Berthelot, G. Raimondo, S. Pol, and C. Brechot. 1997. Mutations in the nonstructural 5A region of hepatitis C virus and response of chronic hepatitis C to interferon alfa. Gastroenterology 113:567-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor, D. R., S. T. Shi, P. R. Romano, G. N. Barber, and M. M. Lai. 1999. Inhibition of the interferon-inducible protein kinase PKR by HCV E2 protein. Science 285:107-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thelu, M. A., M. Baud, V. Leroy, J. M. Seigneurin, and J. P. Zarski. 2001. Dynamics of viral quasispecies during interferon therapy in nonresponder chronic hepatitis C patients. J. Clin. Virol. 22:125-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thimme, R., J. Bukh, H. C. Spangenberg, S. Wieland, J. Pemberton, C. Steiger, S. Govindarajan, R. H. Purcell, and F. V. Chisari. 2002. Viral and immunological determinants of hepatitis C virus clearance, persistence, and disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:15661-15668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toyoda, H., T. Kumada, S. Nakano, I. Takeda, K. Sugiyama, T. Osada, S. Kiriyama, Y. Sone, M. Kinoshita, and T. Hadama. 1997. Quasispecies nature of hepatitis C virus and response to alpha interferon: significance as a predictor of direct response to interferon. J. Hepatol. 26:6-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wasley, A., and M. J. Alter. 2000. Epidemiology of hepatitis C: geographic differences and temporal trends. Semin. Liver Dis. 20:1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeh, B. I., K. H. Han, H. W. Lee, J. H. Sohn, W. S. Ryu, D. J. Yoon, J. Yoon, H. W. Kim, I. D. Kong, S. J. Chang, and J. W. Choi. 2002. Factors predictive of response to interferon-alpha therapy in hepatitis C virus type 1b infection. J. Med. Virol. 66:481-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yuki, N., N. Hayashi, T. Moribe, Y. Matsushita, T. Tabata, T. Inoue, Y. Kanazawa, K. Ohkawa, A. Kasahara, H. Fusamoto, and T. Kamada. 1997. Relation of disease activity during chronic hepatitis C infection to complexity of hypervariable region 1 quasispecies. Hepatology 25:439-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeuzem, S., J. H. Lee, and W. K. Roth. 1997. Mutations in the nonstructural 5A gene of European hepatitis C virus isolates and response to interferon alfa. Hepatology 25:740-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]