Abstract

Background:

Results of endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EUBD) are unknown in case of proximal stricture. The aim is to assess clinical outcomes of EUBD in patients with malignant hilar obstruction.

Methods:

Patients undergoing EUBD with hilar strictures were prospectively included. Primary outcome was clinical success at 7 and 30 days (defined by 50% bilirubin decrease). Secondary outcomes were technical success, procedure-related complications, length of hospital stay, reintervention rate, survival and chemotherapy administration.

Results:

Eighteen patients with a mean age of 68.8 years were included. On 15 classable stenosis, 7 (47%) were noted Bismuth I–II, 7 (47%) Bismuth III, and 1 (6.7%) Bismuth IV. Reasons for EUBD were surgically modified anatomy in 10 patients (55.6%), impassable stricture at ERCP in 7 (38.9%) and duodenal obstruction in 1 (5.6%). Only hepaticogastrostomy was performed. Clinical success was at day 7 and 30 respectively 72.2% and 68.8%. Technical success was 94%. Complications occurred in 3 (16.7%) patients. Median (range) length of hospital stay was 10 (6–35) days. Reintervention rate was 16.7%. Median (range) survival was 79 (5–390) days. Chemotherapy was possible in 10 (55.6%) patients.

Conclusions:

EUBD is feasible for hilar obstruction for surgically altered anatomy or after ERCP failure. Clinical outcome is satisfactory when considering underlying advanced disease, allowing chemotherapy.

Keywords: bridge-trans-hilar stenting, endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage, endoscopic ultrasound hepaticogastrostomy, hilar strictures, modified anatomy

Introduction

Transpapillary bile duct cannulation by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is the technique of choice for palliative as well as pre-operative drainage of distally obstructive jaundice. ERCP can be impossible when previous surgery or proximal digestive obstruction has made the papilla inaccessible. In such cases, endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EUBD), a recent development of interventional endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), can be offered as an alternative to more conventional instrumental (percutaneous transhepatic) or surgical drainage methods. Because EUBD is generally proposed in the case of distal biliary obstruction, there has been no systematic report of the results of EUBD in the case of proximal hilar biliary obstruction. Moreover, ERCP in non-operable hilar stenosis is more challenging than distal obstruction, with a failure rate of up to 27%, and lower clinical efficacy, even after successful stenting.1 For these reasons, we decided to study the outcomes of patients treated by EUBD for proximal malignant biliary obstruction.

Patients and methods

Study design

This is an observational cohort study including consecutive patients with a mostly prospective collection of data. Out of a prospectively maintained and incremented database of EUS-guided interventional procedures starting in November 2013, consecutive patients undergoing EUBD who presented hilar bile duct obstruction were extracted over a period of 2 years, ending in November 2015. Inclusion criteria were: age >18, histologically proven malignant obstruction involving the main biliary confluence (as assessed from MRI) with no access to the papilla or a previous failure to achieve retrograde endoscopic drainage. Exclusion criteria included severe coagulation disorders not amenable to rapid and sustainable correction, large volume ascites (a small amount of ascites was considered acceptable), previous left hepatectomy, CT-scan or MRI showing severe atrophy or massive tumor involvement of the left liver lobe, and non-dilated bile ducts. The study received IRB approval and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Baseline data

Baseline demographic and biological data, information on the patients’ clinical history and current condition were collected prospectively on inclusion. Most short-term follow-up data were also obtained prospectively on patient discharge or from referring physicians. Additional data, both clinical and biological, were obtained when necessary by a retrospective review of medical records. Endoscopic procedure details were immediately recorded. Clinical data included World Health Organization (WHO) status at inclusion, underlying neoplasia, surgical history, previous interventional procedures, significant clinical events, length of hospital stay, medical decisions made after EUBD (chemotherapy, care limitation), clinical events during the first 3 months following EUBD (such as procedure-related complications and reinterventions – whether endoscopic or not) and survival time. Biological data included only total serum bilirubin level (mg/dl) before drainage, 7 days and 30 days after drainage. Patients were followed until death or date of transfer to a palliative care unit.

Outcomes measures

The main outcome measure was clinical success defined by a decrease of total serum bilirubin level to less than half the pre-operative level within 7 (early success) and 30 days (sustained success) of procedure.

Secondary outcome measures included technical success (defined by the possibility of puncturing biliary ducts and inserting a stent between the biliary tree and the stomach or the duodenum), procedure-related complications (within 30 days) and overall complications (within 3 months), administration of chemotherapy, length of hospital stays, reintervention rate and overall survival.

Procedure

All procedures were performed in supine position under monitored general anesthesia with airway intubation. Prophylactic antibiotics were administered before all procedures. One endoscopist (FP) with expertise in ERCP, EUS and EUS-BD performed all procedures.

By using a large-channel curved linear array echo-endoscope (GF-UCT140/180, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), the left hepatic duct was identified from the proximal gastric body and punctured with a 19-gauge needle (EUSN-19A; Cook Endoscopy, Winston-Salem, NC, USA). Color Doppler was used to detect any intervening vessel. After confirming bile aspiration, contrast was injected to obtain a cholangiogram (Figure 1). A 0.035-inch guidewire (Jagwire; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) was then advanced into the intrahepatic biliary ducts. The needle was removed, and the track was coagulated by using a 6 Fr cystostome (Endoflex, Belgium) to facilitate the insertion of a 10 mm large fully covered self-expandable metal stent (FCSEMS) (WallFlex; Boston Scientific or Hanarostent, MI-Tech, Life Partners Europe, Bagnolet, France), generally 80 mm in length, in the left hepatic duct. When the right liver bile ducts appeared to be accessible from the left ducts, an uncovered SEMS bridging the confluence (Zilverstent; Cook Medical) was inserted after guidewire cannulation and balloon dilation if necessary, and before FCSEMS transgastric placement (Figures 2 and 3). A single hemostatic clip was generally used to secure the gastric stent end and reduce the risk of stent migration.

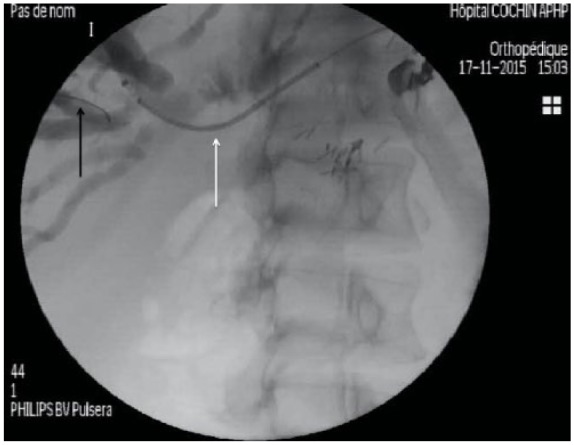

Figure 1.

Opacification of left and right biliary ducts under fluoroscopy (black arrows) that are dilated secondary to Klatskin Bismuth III cholangiocarcinoma. No contrast opacification is seen in the main bile duct (white arrow).

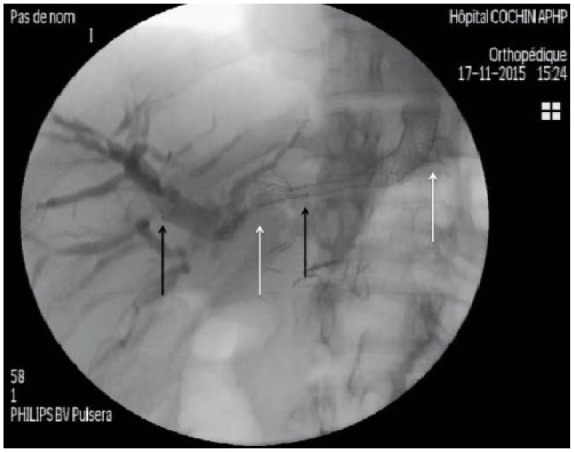

Figure 2.

The 0.035-inch guidewire is placed until the right liver bile ducts (black arrow). A 6 Fr cystostome is used for coagulation to facilitate introduction of FCSEMS (white arrow).

Figure 3.

Bridge-trans-hilar stenting with uncovered metallic stent (black arrows delimiting distal and proximal extremities in right and left bile ducts respectively) and left FCSEMS (white arrows delimiting distal and proximal extremities in left bile ducts and stomach).

Statistical analysis

Only descriptive statistics have been used. Patient characteristics and main results are expressed in this report as proportions. Age, survival and length of hospital stay in days are expressed as mean (± SD) and median (range), whereas bilirubin levels are expressed as mean (± SD).

Results

Patients

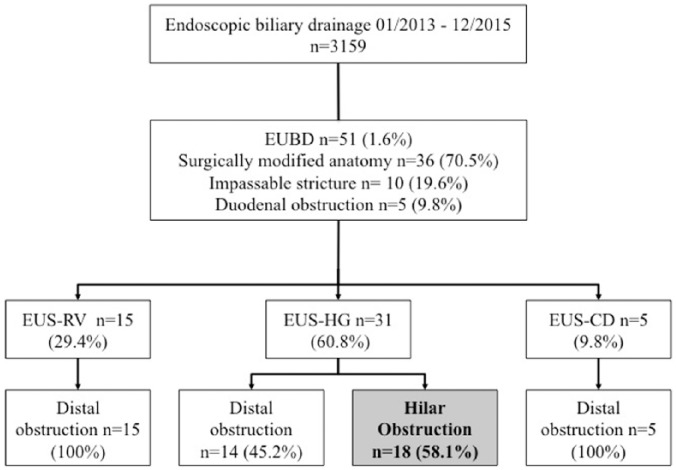

During the study period, 18 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria, out of 52 undergoing EUBD and 3159 referred to our center for ERCP. All 18 patients had EUBD by the transgastric route. A flow chart displays patient selection (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Flow chart with patient selection and distribution. Only patients with proximal biliary obstruction were studied.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. All patients had clinical jaundice at the time of EUBD, but general condition remained good or fair in most patients. The main cause of biliary obstruction was loco-regional recurrence of previously resected biliary (n = 2), gastric (n = 1), and pancreatic (n = 3) adenocarcinoma in six patients (33.3%) followed by hepatic hilar metastases in four patients (22.2%) from colorectal adenocarcinoma (n = 3) and pancreatic adenocarcinoma (n = 1). Pancreatic mass from metastatic adenocarcinoma (n = 3, 16.7%), primary hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Klatskin’s tumor) (n = 3,16.7%) and peritoneal carcinomatosis in two patients (7.6%) from gastric (n = 1) and pancreatic cancers (n = 1) represented following causes of obstruction. Because of previous hepatectomy, only 15 patients presented classable stenosis on Bismuth Classification. Thus, we had seven (47%) patients with Bismuth I–II stenosis, seven (47%) patients with Bismuth III stenosis and one (6.7%) with Bismuth IV stenosis. ERCP was not achievable in 10 patients (55.6%) as a consequence of a modified anatomy after total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y oeso-jejunal anastomosis (n = 3), duodenopancreatectomy with Roux-en Y gastro-jejunal anastomosis (n = 4), or palliative Roux-en-Y reconstruction (n = 3). Other reasons for failure or preclusion of transpapillary drainage were impassable hilar stricture in seven cases (38.9%) and duodenal obstruction caused by pancreatic head carcinoma in one case (5.6%)

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics (n = 18).

| EUBD (n = 18) | |

|---|---|

| Sex, male/female, ratio (%) | 11/7 (61.1) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 68.8 (16.4) |

| median (range) | 74 (35.4–94.4) |

| WHO status, mean (SD) | 2.1 (0.5) |

| Cancer primary: | |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, n (%) | 8 (44.4) |

| Hilar cholangiocarcinoma, n (%) | 5 (27.8) |

| Colorectal adenocarcinoma, n (%) | 3 (16.7) |

| Gastric adenocarcinoma,n (%) | 2 (11.1) |

| Ascites, n (%) | 5 (27.8) |

| Septic cholangitis, n (%) | 9 (50) |

| Total bilirubin, mean (SD), mg/dl | 12.2 (7.3) |

| Hilar obstruction, n (%) | |

| Local recurrence | 6 (33.3) |

| Hepatic metastases | 4 (22.2) |

| Pancreatic mass | 3 (16.7) |

| Hilar cholangiocarcinoma | 3 (16.7) |

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis nodule | 2 (7.1) |

| Reasons for failure or preclusion of transpapillary drainage (%) | |

| Surgically modified anatomy | 10 (55.6) |

| Impassable stricture at ERCP | 7 (38.9) |

| Duodenal obstruction | 1 (5.6) |

| Bismuth Classificationa | |

| I–II | 7 (47.7) |

| III | 7 (47.7) |

| IV | 1 (6.7) |

Exclusion of three patients who presented unclassable hilar stenosis (hepatic surgery) in the Bismuth Classification.

Three patients (16.7%) presented with tissular infiltration of a hepatico-jejunal anastomosis after right hepatectomy involving the hilum; the other 15 (83.3%) had an advanced hilar stricture. A clip was used to avoid migration in seven patients (38.9%).

Outcome of endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage

Outcome results are shown in Table 2. EUBD was technically successful in 17 patients (technical success rate = 94%).

Table 2.

EUBD results of malignant proximal biliary obstruction.

| EUBD (n = 18) | |

|---|---|

| Technical success of hepaticogastrostomy, n (%) | 17 (94) |

| Technical success of bridge-trans-hilar stenting, n (%)a | 3 (50) |

| Clinical success, n (%) | |

| Early (at 7 days) | 13 (72.2) |

| Sustained (at 30 days) b | 11 (68.8) |

| Total bilirubin, mean (SD), mg/dl | |

| 1 week | 6.5 (5) |

| 1 month | 3.8 (5.8) |

| Reintervention rate, n (%) | 3 (16.7) |

| Hospitalization length, days median (range) | 10 (6–35) |

| Complication rates at 3 months, n (%) | 3 (16.7) |

| Procedure-related mortality <1 week n (%) | 1 (5.6) |

| Overall survival, days, median (range) | 79 (5–390) |

| Chemotherapy administration, n (%) | 10 (55.6) |

| Overall survival of patients with chemotherapy, days, median (range) | 210 (32–390) |

Six attempts to put bridge-trans-hilar prosthesis in five patients.

Two patients excluded because of early death with no connection to drainage.

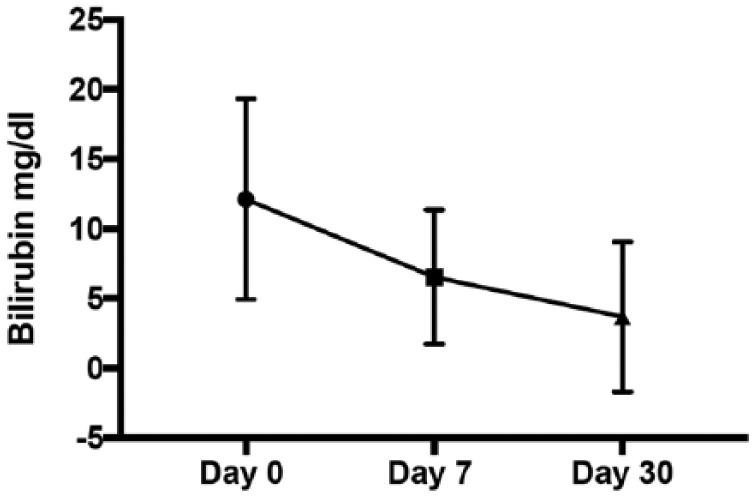

Early clinical success (within seven days of EUBD procedure) was observed in 13 out of 18 patients (72.2%). Two patients died of advanced cancer, but without biliary complications at 10 and 11 days. Sustained clinical success at 30 days was observed in 11 of the 16 remaining patients (68.8%). Total bilirubin mean (±SD) serum level declined from 12.1 (±7.2) mg/dl to 6.5(±5) mg/dl at 1 week and 3.8 (±5.8) mg/dl at 1 month, a decrease of respectively 46.3% and 68.6% from baseline, as represented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Total bilirubin mean before drainage, at day 7 and day 30.

Attempts to bridge-stent the main confluence were successful in three out of six procedures (50%) for five patients (three unsuccessful attempts in two patients for tight hilar strictures). Among those patients with attempted bridge-trans-hilar stenting, specific early and sustained clinical success was 60% (3/5).

When advanced strictures were considered (>Bismuth II) regarding eight patients, early and sustained success was observed in five patients (62.5%) for whom four bridge-stent hilar stenting were attempted in three patients and all achieved.

Reinterventions were needed in three patients (16.7%) after one case of migration of the hepatico-gastric stent and two failure cases of bridge-trans-hilar stenting. Median and mean lengths of hospital stay after EUBD were respectively 10 (6–35) and 12.8 (±7.8) days, and median and mean overall survivals were respectively 93 (5–410) and 133.8 (127.7) days. Three procedure-related complications were observed (16.7%). One patient developed a severe hemorrhage at the point of gastro-hepatic puncture 5 days after EUBD, causing the only procedure-related death of the study. One jaundice observed 60 days after EUBD was deemed secondary to the transgastric FCSEMS clogging, but no attempt at stent desobstruction was undertaken after collegial decision to limit care in a patient with a terminal-stage pancreatic cancer. The third complication observed was a stent migration 2 months after procedure, treated with a new procedure. No case of peritoneal bile leak was observed. Within 30 days of EUBD, chemotherapy was resumed in 10 (55.6%) patients for an overall survival of 210 (32–390) days. Among patients who could not receive cytotoxic drugs, four patients had too high bilirubin rates, one patient presented a WHO score >2, two patients died of cancer without biliary complications, and one patient died of biliary complication.

Discussion

This observational study is dedicated to the outcome of EUBD in case of proximal biliary obstruction. Many reports have recently shown that EUBD is an interesting technique when ERCP is not possible, whether due to a surgically altered anatomy or to a proximal gastroduodenal obstruction.2–5 However, since the right liver accounts for approximately 60–70% of the hepatocellular mass and EUBD gives access in most cases to the left ducts (except, but randomly, in case of transduodenal EUBD), this technique tends to be limited to distal obstruction, in which all EUBD approaches (transduodenal, transgastric and by transhepatic rendezvous) are in theory equally valid.4,6,7 The common approach to cases of hilar obstruction after ERCP failure or when access to the major papilla is barred is to refer the patient to the interventional radiologist for a percutaneous transhepatic drainage, in which case left and right liver accesses are available and multiple stenting is possible even for advanced strictures. However, percutaneous drainage is associated with higher morbidity than ERCP and is not recommended in case of ascites and massive one-sided tumor involvement, thus sometimes restricting available access routes.8–10 The other alternative interventional option of enteroscopy-guided retrograde drainage is poorly attractive since papillary access is successful in only 60–70% of patients, is very time-consuming and has few drainage options for advanced strictures as a consequence of small scope working channel and fewer ancillary devices to conduct complex procedures.4 It was therefore interesting to investigate to what extent EUBD could provide jaundice relief even when limited to the left liver lobe, with the knowledge acquired from ERCP studies showing that in selected cases one-sided ERCP drainage of advanced hilar strictures could be efficient.1,11 Our study shows that EUBD in such patients has a high technical success rate (94%), which was expected, but also a satisfactory rate of clinical success (around 70%), allowing patients to receive additional chemotherapy (55.6%) otherwise precluded by obstructive jaundice, and a low rate of complications (16.7%).

Technical EUBD success rate was similar to other EUBD studies.12 In only one patient did the left duct puncture and stenting fail because bile ducts were not dilated. When comparing patients in this study with our experience of EUBD in patients with distal obstruction, we found a similar technical success rate (100%). It is important to note that all patients with proximal obstruction in our series had EUBD through the transgastric route. This approach has been preferred in our experience for its absence of significant infectious complications and possibly lower rate of bile leaks. Moreover, EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy is often the only available EUBD option, since the transduodenal route does not permit the puncture of intrahepatic ducts and the rendezvous technique is either impossible (previous surgery) or difficult for the same reasons that led to ERCP failure.12

Clinical success rates in the range of 75–100% have been reported after EUBD, but poorly defined criteria for clinical success and inclusion of mostly distal strictures may account for the difference, with a much higher chance of rapid jaundice relief in distal strictures.12 In our own experience of EUBD in distal biliary strictures, clinical success was 86%.13 Moreover, since it has been previously proven that draining >50% of the liver volume may be an important predictor of success (especially in advanced Bismuth III–IV hilar strictures), left lobe drainage could be sufficient in patients with a large left liver.1,11,14 However, clinical success was more rapid when bridging the obstructed main confluence with an uncovered stent when successfully attempted, although 3/5 such attempts failed. Such procedures can be very demanding and must probably be attempted in only some specific, carefully selected cases, when the right–left balance of functional liver mass suggests a particular advantage of draining at least part of the right lobe and provided that guidewire loops in the hilum can be avoided or reduced before reaching the right sectors.

Artifon and colleagues, in a single-center randomized study, did not find any difference after ERCP failure between EUS-choledochoduodenostomy and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) in terms of efficacy and safety, but only distal stenosis were studied (malignant involvement of the second portion of the duodenum and the major papilla).15 In a recent work of percutaneous transhepatic biliary metal stenting for malignant hilar obstruction looking at predictive factors for efficacy in 159 patients from a single center, Li and colleagues reported a technical success rate of 100% and a clinical success of 71.4%.16 These outcomes are similar to ours, except that clinical success in Li’s study was defined by a decrease of only 30% at 7 days. Morbidity results from Li’s study (26.4%) suggest more severe and more frequent complications than after EUBD. Direct comparisons with our results are not possible, but this indicates that EUBD and PTBD might have similar efficacies in hilar obstructions. Moreover, PTBD may need reinterventions especially when the most common two-step approach is chosen, with an external drain in place for a few days before stenting. As with Artifon and colleagues, a recent prospective study comparing EUBD in our center and PTBD by an expert interventional radiologist for proximal and distal biliary obstruction found similar success and adverse events rate but a lower number of reintervention and length of hospitalization favoring EUBD.

As long as a patient with non-curable malignant disease remains in fair condition and is willing to undergo additional treatments to extend survival and improve comfort, the current trend in clinical oncology is to offer chemotherapy whenever possible. Most chemotherapy requires good liver function and an effective biliary clearance. Effective biliary drainage is therefore a prerequisite, not only for the patient’s quality of life and nutritional stabilization, but also to allow chemotherapy to be administered. We found no published result of that kind in EUBD studies, but in a retrospective study of 71 patients with advanced solid malignancies and hilar biliary obstruction treated with PTBD, chemotherapy administration was possible in 55% of patients17 – that is, exactly the same rate as in the present study. Moreover, EUBD in this subgroup of patients who could receive chemotherapy allowed high overall survival at 210 (32–390) days.

The complication rate of 16.7% is lower than the 22% rate reported in Park’s meta-analysis,12 and can be deemed acceptable, but it must be noted that one of our patients died from severe bleeding a few days after EUBD. Bleeding and bile leak are the two most serious complications to be anticipated after EUBD and must be prevented as much as possible by a perfect correction of coagulation and an expert handling of the EUBD procedure.

The present work presented one main limitation, which was the small number of patients because EUBD after ERCP failure is not well known among oncologists, who still address patients for PTBD.

Conclusion

EUBD is a feasible and effective technique for proximal biliary obstruction after ERCP failure, as well as in patients with surgically altered anatomy. Bridge-trans-hilar stenting can be attempted in selected cases, with a lower feasibility rate but good clinical outcome when successful. EUBD can make chemotherapy feasible.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Frédérick Moryoussef, Department of Gastro-Enterology, La Pitié Salpetrière Teaching Hospital, AP-HP, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France.

Adrien Sportes, Department of Gastro-Enterology, Cochin Teaching Hospital, AP-HP, Université Paris Descartes, Sorbonne Paris Cite, Paris, France.

Sarah Leblanc, Department of Gastro-Enterology, Cochin Teaching Hospital, AP-HP, Université Paris Descartes, Sorbonne Paris Cite, Paris, France.

Jean Baptiste Bachet, Department of Gastro-Enterology, La Pitié Salpetrière Teaching Hospital, AP-HP, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France.

Stanislas Chaussade, Department of Gastro-Enterology, Cochin Teaching Hospital, AP-HP, Université Paris Descartes, Sorbonne Paris Cite, Paris, France.

Frédéric Prat, Department of Gastro-Enterology, Cochin Teaching Hospital, AP-HP, Université Paris Descartes, Sorbonne Paris Cite, Paris, France.

References

- 1. Park YJ, Kang DH. Endoscopic drainage in patients with inoperable hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Korean J Intern Med 2013; 28: 8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Giovannini M, Moutardier V, Pesenti C, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided bilioduodenal anastomosis: a new technique for biliary drainage. Endoscopy 2001; 33: 898–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Artifon ELA, Marson FP, Gaidhane M, et al. Hepaticogastrostomy or choledochoduodenostomy for distal malignant biliary obstruction after failed ERCP: is there any difference? Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 8: 950–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hara K, Yamao K, Mizuno N, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage: who, when, which, and how? World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22: 1297–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Park DH. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided hepaticogastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2012; 22: 271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ogura T, Sano T, Onda S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage for right hepatic bile duct obstruction: novel technical tips. Endoscopy 2015; 47: 72–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Park SJ, Choi J-H, Park DH, et al. Expanding indication: EUS-guided hepaticoduodenostomy for isolated right intrahepatic duct obstruction (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 78: 374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Inamdar S, Slattery E, Bhalla R, et al. Comparison of adverse events for endoscopic vs percutaneous biliary drainage in the treatment of malignant biliary tract obstruction in an inpatient national cohort. JAMA Oncol 2016; 2(1): 112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tsetis D, Krokidis M, Negru D, et al. Malignant biliary obstruction: the current role of interventional radiology. Ann Gastroenterol Q Publ Hell Soc Gastroenterol 2016; 29: 33–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Uberoi R, Das N, Moss J, et al. British Society of Interventional Radiology: Biliary Drainage and Stenting Registry (BDSR). Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2012; 35: 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vienne A, Hobeika E, Gouya H, et al. Prediction of drainage effectiveness during endoscopic stenting of malignant hilar strictures: the role of liver volume assessment. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72: 728–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Park DH. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage of hilar biliary obstruction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2015; 22: 664–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sportes A, Camus M, Greget M, et al. Comparative trial of EUS guided hepatico-gastrostomy and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage for malignant obstructive jaundice after failed ERCP. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bulajic M, Panic N, Radunovic M, et al. Clinical outcome in patients with hilar malignant strictures type II Bismuth-Corlette treated by minimally invasive unilateral versus bilateral endoscopic biliary drainage. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2012; 11: 209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Artifon ELA, Aparicio D, Paione JB, et al. Biliary drainage in patients with unresectable, malignant obstruction where ERCP fails: endoscopic ultrasonography-guided choledochoduodenostomy versus percutaneous drainage. J Clin Gastroenterol 2012; 46:768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li M, Bai M, Qi X, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary metal stent for malignant hilar obstruction: results and predictive factors for efficacy in 159 patients from a single center. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2015; 38:709–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crosara TM, Mak MP, Marques DF, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage in patients with advanced solid malignancies: prognostic factors and clinical outcomes. J Gastrointest Cancer 2013; 44: 398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]