Abstract

Median survival for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer (MPC) treated with combination chemotherapeutic agents such as gemcitabine-based regimens and FOLFIRINOX is currently less than 12 months. This highlights the need for more efficacious first-line, as well as second-line therapies. Nanoliposomal irinotecan, in combination with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)/folinic acid has recently been assessed as second-line therapy after initial gemcitabine-based therapy. It is the first, second-line treatment approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat patients with MPC based on results of the NAnoliPOsomaL Irinotecan (NAPOLI-1) study, which showed that this regimen significantly prolonged progression-free survival (3.1 months versus 1.5 months) and overall survival (6.2 months versus 4.1 months) compared with 5-FU/folinic acid alone. In addition, this study also represented an important step forward in improving the efficacy of previously used chemotherapeutic agents by using nanoformulation to extend pharmacokinetic advantages such as slow clearance, low steady-state volume of distribution, and longer half-life. However, certain adverse effects that are seen more frequently with nanoliposomal irinotecan and 5-FU/folinic acid, compared with 5-FU/folinic acid alone, include neutropenia, fatigue, diarrhea, and nausea/vomiting. This merits close monitoring of patients who are on this combination, since these adverse events may necessitate dose reductions and growth factor support. It is imperative to check UGT1A1 gene status in all patients being considered for treatment with nanoliposomal irinotecan. Patients found to be homozygous for the UGT1A1*28 gene need to be started on a lower initial dose. As we gain more data with clinical use, we anticipate further characterization of the aforementioned toxicities in patients with UGT1A1 gene polymorphisms and other genetic variants.

Keywords: gemcitabine, irinotecan liposome injection, nanoliposomal irinotecan, pancreatic cancer

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is currently the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the USA. This is second only to colorectal cancer as a cause of gastrointestinal cancer-related death [Fernandez-del Castillo et al. 2016]. Overall, pancreatic cancer represents the eighth leading cause of cancer-related mortality in men (138,100 deaths annually) and the ninth in women (127,900 deaths annually) in the world [Jemal et al. 2011]. Its incidence in the general population is estimated to be 8.8 per 100,000, however, the disease is rarely seen in patients younger than 45 years [Ries et al. 2002]. In the USA, approximately 53,070 patients are diagnosed with pancreatic cancer annually, and almost all unfortunately are expected to die from the disease [Siegel et al. 2016]. In general, the ethnicities with the highest incidence of pancreatic cancer include Maoris, native Hawaiians, and African-American populations, while people living in India and Nigeria have the lowest reported incidence [Hariharan et al. 2008].

Incidence and death rates vary by gender and race [Zhang et al. 2008]. The incidence is greater in men than women (male-to-female ratio 1.3:1), and in blacks (14.8 per 100,000 in black males compared with 8.8 per 100,000 in the general population) [Ries et al. 2002]. However, more recently, data suggest that these ethnic differences may be decreasing [Ma et al. 2013].

Surgical resection is a potentially curative treatment, but unfortunately, only 20% of patients with malignancy limited to the pancreas are candidates for pancreatectomy. In 80% of patients, there is regional tumor extension or distant metastasis at presentation, thus chemotherapy is the primary treatment [Ma et al. 2016]. Chemotherapy remains the mainstay of treatment for patients diagnosed with metastatic pancreatic cancer and provides benefit in terms of symptomatic relief and survival [Oettle et al. 2014].

First-line treatment of metastatic pancreatic carcinoma: a historical perspective

Chemotherapy remains the mainstay of treatment for patients diagnosed with metastatic pancreatic carcinoma (MPC). The first randomized controlled trial which showed a survival advantage in patients with unresectable pancreatic carcinoma used 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), methotrexate, vincristine, and cyclophosphamide which resulted in overall survival of 44 weeks compared with 9 weeks with best supportive care (BSC) [Mallinson et al. 1980]. Palliative chemotherapy with 5-FU has been a historical benchmark in the treatment of MPC and studies reveal a radiographic objective response rate of 0–9% and a rise in a median survival of 2.5–6 months [Crown et al. 1991; DeCaprio et al. 1991; Van Rijswijk et al. 2004]. However despite attempts to utilize additional agents including doxorubicin, actinomycin-D, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and vincristine, either alone or in combination with 5-FU, none of those regimens increased survival beyond 6 months [Schein et al. 1978; Kelsen et al. 1991; Cullinan et al. 1990].

In 1997, gemcitabine was established as a new standard of care showing superiority over 5-FU after the results published by Burris and colleagues. In this randomized controlled trial, gemcitabine was compared with 5-FU in 126 patients. The study did not show significant differences in objective response rate. However, it demonstrated improvement in median overall survival (5.65 months versus 4.41 months) and 1-year survival rates (18% versus 2%). It also showed improvement in quality-of-life measures, that is, clinical benefit response (23.8% versus 4.8%), which was a composite measure of pain, Karnofsky performance status, and weight [Burris et al. 1997].

Genetic studies reveal that pancreatic cancers often express epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs). Therefore, the addition of molecular-targeted therapy (against EGFRs) to gemcitabine was evaluated [Bruns et al. 2000]. In 2007, gemcitabine was compared with gemcitabine plus erlotinib, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor that binds to the EGFR [Moore et al. 2007]. There were no significant differences in objective response rate. However, the gemcitabine plus erlotinib group exhibited an improvement in median overall survival (6.24 months versus 5.91 months) and 1-year survival rates (23% versus 17%). Despite approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the use of erlotinib has not been widely practiced due to its modest incremental survival benefit when added to gemcitabine (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.81) for overall survival and substantial toxicities. In 2010, gemcitabine was compared with gemcitabine plus cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody against EGFRs. This study did not demonstrate significant differences in median overall survival, progression-free survival, and objective response rate [Philip et al. 2010].

The ACCORD trial used FOLFIRINOX, a multidrug combination agent consisting of bolus plus infusional 5-FU, folinic acid, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin administered on a biweekly dosing schedule to single-agent gemcitabine in patients with previously untreated MPC and intact functional status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–1) [Conroy et al. 2011]. The study established FOLFIRINOX as a first-line therapy for patients with MPC and good performance status. The FOLFIRINOX group had improvements in objective response rate (31.6% versus 9%, p < 0.001), median progression-free survival (6.4 months versus 3.3 months; p < 0.001), and overall survival (11.1 months versus 6.8 months). However, the superiority of FOLFIRINOX was at the cost of greater toxicities and only feasible in a subset of patients who were able to tolerate aggressive chemotherapy [Ur Rehman et al. 2016; Ko, 2016].

Based on the MPACT trial, a combination chemotherapy regimen of gemcitabine and 130 nm albumin-bound formulation of paclitaxel particles (nab-paclitaxel, Celgene, Summit, NJ, USA) has recently been approved by the FDA for advanced pancreatic cancer. In this trial 861 patients with MPC were randomized to receive gemcitabine alone or in combination with nab-paclitaxel [Von Hoff et al. 2013]. Patients receiving nab-paclitaxel had superior outcomes compared with those receiving gemcitabine alone. These included a significantly improved median overall survival (8.5 months versus 6.7 months,p < 0.001), progression-free survival (5.5 months versus 3.7 months, p < 0.001), and tumor response rate (23% versus 7%; p < 0.001, respectively), thus leading to FDA approval of nab-paclitaxel for this indication in 2014 [Ko, 2016; Von Hoff et al. 2013].

Second-line treatment of MPC

Although standard of care for treatment of pancreatic cancer has been established in the first-line setting since 1997, there are limited data to support standard of care for second-line chemotherapy in MPC. Since the recent FDA approval of nanoliposomal irinotecan (Onivyde) as a second-line agent for MPC, the landscape of treatment may change.

What is nanoliposomal irinotecan and what is its role in MPC?

Nanoliposomal irinotecan (OnivydeTM, Merrimack Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA, USA) was approved by the FDA in October 2015, in combination with 5-FU and folinic acid (leucovorin), for the treatment of patients with MPC after disease progression following gemcitabine-based therapy [Oettle et al. 2014].

Nanoliposomal irinotecan inhibits the activity of topoisomerase I resulting in DNA damage and subsequent apoptosis [Oettle et al. 2014]. Following administration, nanoliposomal irinotecan remains 95% encapsulated within a lipid bilayer vesicle. The liposomal bilayer protects irinotecan from conversion to its active metabolite (SN-38) in the circulation, thereby increasing intratumoral levels of both irinotecan and SN-38. Local metabolic activation increases its therapeutic window and potentially minimizes toxicity [Wang-Gillam et al. 2016; Carnivale and Ko, 2016]. The metabolism of the nanoliposomal irinotecan formulation has not been thoroughly evaluated. However, following intravenous administration, standard irinotecan undergoes metabolism via esterases to SN-38. This metabolite is subsequently activated by uridine diphosphate glucuronosyl transferase (UGT1A1). Patients homozygous for the UGT1A1*28 allele achieve higher levels of SN-38. Therefore, these individuals may require lower dosages of irinotecan [Chang et al. 2015; Drummond et al. 2006].

The initial starting dose of the nanoliposomal irinotecan base is 70 mg/m2. The dose is infused over 90 min, every 2 weeks prior to folinic acid and FU. In patients, homozygous for the UGT1A1*28 allele, the starting dose is reduced to 50 mg/m2 administered by intravenous infusion over 90 min. The dose may be increased up to 70 mg/m2 as tolerated in subsequent cycles.

Nanoliposomal irinotecan, in combination with folinic acid and 5-FU, is emerging as an acceptable second-line option in patients with MPC previously treated with gemcitabine-based therapy. This regimen is more expensive than FOLFOX, another second-line treatment regimen. Compared with the irinotecan base (100 mg/5 ml), which costs US$470.70, one vial (10 ml of 4.3 g/ml) of liposomal irinotecan costs US$1704.56. Despite its higher cost, it may represent a possible alternative in patients with disease regression who may not be able to tolerate FOLFOX therapy [Oettle et al. 2014].

Second-line treatment in MPC: clinical trials in perspective

Pancreatic cancer that demonstrates disease progression after gemcitabine-based regimens poses a serious challenge to patient management. Pelzer and colleagues initiated a phase III multicenter study comparing oxaliplatin, folinic acid, and 5-FU (OFF) versus BSC in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer progressing while on gemcitabine therapy [Pelzer et al. 2011]. After the inclusion of 46 patients, the trial was terminated due to lack of acceptance of BSC by patients and physicians. Median overall survival for the patients allocated to OFF was 9.09 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 6.97–11.21) compared with 7.90 months (95% CI: 4.95–10.84) for patients in the BSC arm (0.50 [95% CI: 0.27–0.95]; p = 0.031). Despite its premature termination, this randomized trial provided evidence for the benefit of second-line chemotherapy compared with BSC alone for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

Subsequently, a phase III, open-label randomized controlled trial including 168 patients was performed (CONKO-003). During this study, the OFF regimen was compared with folinic acid and fluorouracil (FF) alone [Oettle et al. 2014]. Median overall survival was significantly better in the OFF regimen compared with FF (5.9 months and 3.3 months, respectively, HR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.48–0.91; p = 0.01). The most frequent adverse effects in the group receiving the OFF regimen were grade 1–2 paresthesia (38.2%) and grade 3 paresthesia (4.0%).

To date, there are no prospective trials for FOLFIRINOX as second-line therapy (short-term infusional 5-FU, folinic acid, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin) in patients treated initially with gemcitabine-based therapy. In a retrospective single-center study including 27 patients, this combination was found to be associated with a median time to tumor progression of 5.4 months, while the median overall survival in this patient group was 8.5 months. Grade 3–4 neutropenia occurred in 15 out of 27 patients [Assaf et al. 2011].

Nanoliposomal irinotecan as monotherapy for the treatment of gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer was first evaluated in a phase II study in 2013 [Ko et al. 2013]. A total of 40 patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma, Karnofsky performance status of 70 or greater, with documented progression following gemcitabine-based therapy were eligible. A dose of 120 mg/m2 of nanoliposomal irinotecan (PEP02) was administered every 3 weeks. The primary endpoint used in this study was 3-month survival. Results revealed that 30 patients (75%) survived at 3 months. Further analysis showed median progression-free survival and overall survival of 2.4 months and 5.2 months, respectively. The most common severe adverse events included neutropenia, abdominal pain, asthenia, and diarrhea.

Role of nanoliposomal irinotecan in other gastrointestinal malignancies

The PEPCOL (PEP02 in colorectal cancer) study was undertaken to evaluate therapy for second-line metastatic colorectal cancer. It revealed that the partial response rate for folinic acid/5-FU/nanoliposomal irinotecan was 14.3% and progression-free survival was 5.0 months. These response rates were comparable with those in the mFOLFIRI-3 (modified 5-FU/folinic acid and irinotecan) arm of that study [Chibaudel et al. 2016].

In a phase II study for the second-line treatment of gastric and esophagogastric junction cancers, nanoliposomal irinotecan was comparable with irinotecan or docetaxel, with the overall response rate of 13.6% versus 15.9% observed with docetaxel [Roy et al. 2013]. These studies subsequently paved the way for the phase III NAPOLI-1 trial.

NAPOLI-1 trial

The phase III NAPOLI-1 study was an open-label, randomized controlled trial at 76 sites in 14 countries involving patients with metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma who demonstrated disease progression after previous gemcitabine-based therapy in a neoadjuvant, adjuvant, locally advanced, or metastatic setting [Wang-Gillam et al. 2016]. Important inclusion criteria were: (a) Karnofsky performance status score ≥ 70; (b) adequate hematological (including absolute neutrophil count >1.5 × 109 cells/L); (c) adequate hepatic function (including normal serum total bilirubin, according to local institutional standards, and albumin levels ≥ 30 g/L); (d) adequate renal function. Randomization was made on the basis of baseline albumin levels (≥ 40 g/L versus < 40 g/L), Karnofsky performance status (70 and 80 versus ≥ 90), and ethnic origin (white versus East Asian versus all others).

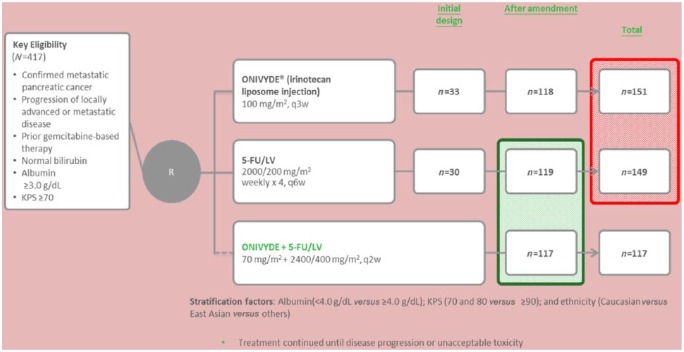

A total of 417 patients were included in this study. These patients were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive nanoliposomal irinotecan monotherapy (120 mg/m2 every 3 weeks, equivalent to 100 mg/m2 of irinotecan base) (n = 151), 5-FU and folinic acid (n = 149), or nanoliposomal irinotecan (80 mg/m2, equivalent to 70 mg/m2 of irinotecan base) with FU and folinic acid every 2 weeks (n = 117) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schema of the NAPOLI-1 study. FU, fluorouracil; KPS, Karnofsky performance status; LV, leucovorin.

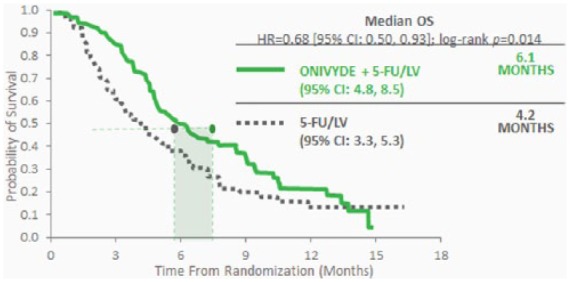

The primary endpoint utilized in this trial was overall survival, assessed in the intention-to-treat population. Median overall survival in patients assigned to nanoliposomal irinotecan plus 5-FU and folinic acid was better compared with 5-FU and folinic acid, that is, 6.1 months (95% CI: 4.8–8.9) versus 4.2 months (3.3–5.3) (HR: 0.67, 95% CI: 0.49–0.92; p = 0.012) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Median survival in the NAPOLI-1 study. CI, confidence interval; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; HR, hazard ratio; LV, leucovorin; OS, overall survival.

No difference in median overall survival was observed between patients assigned to nanoliposomal irinotecan monotherapy and those allocated to 5-FU and folinic acid (4.9 months [4.2–5.6] versus 4.2 months [3.6–4.9]; 0.99, 0.77–1.28; p = 0.94). Notably with respect to overall survival, the control arm in NAPOLI-1 performed better than the historical control observed in CONKO-003 (3.3 months in CONKO-003 versus 4.2 months in NAPOLI-1). However, the same dose and schedule of 5-FU and folinic acid were used as control in both of these studies. A total of 19 (16%) patients assigned to nanoliposomal irinotecan plus 5-FU and folinic acid achieved an objective response compared with 1 patient (1%) allocated to 5-FU and folinic acid (p < 0.0001). A total of 9 (6%) patients randomized to monotherapy with nanoliposomal irinotecan achieved an objective response compared with 1 (1%) of 149 patients assigned to FU and folinic acid (p = 0.02). Factors associated with improved overall survival in patients who were assigned nanoliposomal irinotecan plus 5-FU and folinic acid versus 5-FU and folinic acid alone included: (a) Karnofsky performance score < 90; (b) a concentration of albumin < 40 g/L, (c) CA19-9 antigens > 40 IU/ml; (d) renal function.

This landmark trial led to approval of nanoliposomal irinotecan in combination with 5-FU and folinic acid by the FDA in October 2015 to treat patients with MPC previously treated with gemcitabine-based chemotherapy (http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm468654.htm; accessed 25 September 2015) [Ma et al. 2016].

Genetic polymorphisms

In today’s era of personalized oncology, it is vitally important to identify germline genetic variations that can lead to pharmacokinetic variability of chemotherapeutic agents. This information also finds application in genotype-driven dosing in each individual. Since liposomal irinotecan has recently been approved, pharmacogenomic data on nanoliposomal irinotecan are not available. Therefore, the accuracy with which pharmacogenomic data of free irinotecan base can be extrapolated to nanoliposomal irinotecan is undetermined.

With reference to irinotecan, certain genetic polymorphisms have a significant impact on the circulating level of its active metabolite SN-38, and hence on the estimation of maximum tolerated dose and prediction of dose-limiting toxicities. UGT1A1 is an enzyme involved in the glucuronidation of SN-38 to the inactive metabolite SN-38G [Wang-Gillam et al. 2016]. The homozygous variant of UGT1A1*28 allele (occasionally the heterozygous variant as well) has an association with diminished SN-38 glucuronidation. This leads to increased exposure to the active irinotecan metabolite SN-38, and a substantially increased risk of irinotecan-related toxicity, especially with regards to grade 3–4 neutropenia and diarrhea [Toffoli et al. 2006; Han et al. 2006; Phelps and Sparreboom, 2014; Liu et al. 2014]. Heterozygous or homozygous polymorphisms in the UGT1A1*6 variant (alone or combined with UGT1A1*28 heterozygous polymorphism) have been associated with an increased incidence of severe neutropenia in patients receiving irinotecan [Onoue et al. 2009; Cheng et al. 2014].

The phase II study on the role of liposomal irinotecan in metastatic gastric cancer demonstrated that heterozygosity for the UGT1A1*6 enzyme was associated with increased frequency of grade 3–4 neutropenia compared with wild type [Cheng et al. 2014]. However, in the phase II study carried out by Ko and colleagues no correlation between UGT1A1 genetic polymorphisms and toxicities of nanoliposomal irinotecan was found [Ko et al. 2013]. In the NAPOLI-1 study, 14 recipients of nanoliposomal irinotecan were homozygous for UGT1A1*28 [Wang-Gillam et al. 2016]. One of those 14 patients discontinued therapy due to grade 3 vomiting while another patient required further dose reduction to 40 mg/m2. Three out of seven homozygous patients for UGT1A1*28 in the combination regimen group were able to escalate back to the standard initial dose.

Due to the paucity of data on the pharmacogenomics of patients undergoing treatment with nanoliposomal irinotecan, further studies are warranted to elucidate changes in dosage needed with specific polymorphisms. However, until such studies are available, FDA recommends testing for UGT1A1 polymorphisms and dose reducing by 20 mg/m2 initially, with subsequent dose increase in the absence of drug-related toxicities.

Toxicity of liposomal irinotecan

The NAPOLI 1 study is the largest study to date involving liposomal irinotecan [Wang-Gillam et al. 2016]. Table 1 shows a comparison of toxicities observed in the three treatment arms in that study. The most common adverse events of all grades in patients whose treatment included nanoliposomal irinotecan were neutropenia, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Adverse events that resulted in a dose reduction occurred in 39 (33%) patients in the nanoliposomal irinotecan/5-FU/folinic acid group, 46 (31%) patients in the nanoliposomal irinotecan monotherapy group, and 5 (4%) patients who received 5-FU and folinic acid alone. Grade 3–4 neutropenic sepsis was observed in nine (9%) patients who received nanoliposomal irinotecan (either in combination or as monotherapy) with no events reported in the control group. The need to administer granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was observed in 20 (17%) patients receiving nanoliposomal irinotecan/5-FU/folinic acid compared with 17 (12%) patients in the nanoliposomal irinotecan monotherapy arm and 1 (1%) patient in the FU and folinic acid group.

Table 1.

Grade 3–4 adverse reactions.

| Toxicity | Nanoliposomal irinotecan + 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin (n = 117) |

5-fluorouracil/leucovorin

(n = 134) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grades 3–4 | Any grade | Grades 3–4 | |

| Diarrhea | 69 (59) | 15 (13) | 35 (26) | 6 (4) |

| Vomiting | 61 (52) | 13 (11) | 35 (26) | 4 (3) |

| Nausea | 60 (51) | 9 (8) | 46 (34) | 4 (3) |

| Fatigue | 47 (40) | 16 (14) | 37 (28) | 5 (4) |

| Neutropenia† | 46 (39) | 32 (27) | 7 (5) | 2 (1) |

| Anemia | 44 (38) | 11 (9) | 31 (23) | 9 (7) |

Out of 47 patients who died during the study or within 30 days of the last dose of study drug, 5 had their death attributed directly to the treatment. The most common treatment-attributable adverse events that led to mortality included gastrointestinal toxic effects (nanoliposomal irinotecan monotherapy), infectious enterocolitis (nanoliposomal irinotecan monotherapy), septic shock (nanoliposomal irinotecan plus 5-FU and folinic acid), and disseminated intravascular coagulation with pulmonary embolism (nanoliposomal irinotecan monotherapy).

Due to the adverse effects mentioned above, the recommendations for patients who experience grade 3–4 adverse toxicities are to stop nanoliposomal irinotecan for that treatment [Passero et al. 2016]. It is recommended that complete blood cell count be monitored on days 1 and 8 of every cycle, or more frequently if clinically indicated. It is also recommended to withhold liposomal irinotecan if the absolute neutrophil count drops below 1500/mm3 or the patient develops febrile neutropenia. Liposomal irinotecan should also be withheld in the setting of grade 2–4 diarrhea. Loperamide or subcutaneous atropine (0.25–1 mg) is recommended for late or early onset diarrhea of any severity, respectively. Once there is recovery to grade 1 diarrhea, liposomal irinotecan can be resumed at a reduced dose. Since liposomal irinotecan can lead to severe interstitial lung disease, it is recommended to withhold it in patients with new or progressive dyspnea, cough, and fever, pending diagnostic evaluation (http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/207793lbl.pdf).

Reduction in dose of nanoliposomal irinotecan is recommended in patients without UGT1A1*28 homozygosity who demonstrate recovery to at least grade 1 toxicity following a grade 3–4 adverse event. The dose reduction should be from 70 mg/m2 to 50 mg/m2 after the first occurrence and from 50 mg/m2 to 43 mg/m2 after the second occurrence. For homozygous patients without previous dose increment to 70 mg/m2, the recommended dose reductions in the case of grade 3–4 toxicities is from 50 mg/m2 to 43 mg/m2, and to 35 mg/m2 in the case of first and second adverse events, respectively [Passero et al. 2016].

Future of treatment

As the first second-line agent approved by FDA when given in combination with 5-FU and folinic acid, nanoliposomal irinotecan offers a new avenue in the second-line treatment of pancreatic cancer for patients who have previously failed gemcitabine. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) immediately added nanoliposomal irinotecan (Onivyde) to the treatment algorithm for pancreatic cancer after its approval as evidence level 1 (http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/207793lbl.pdf). Ongoing clinical trials utilizing irinotecan in second-line treatment for patients with recurrent pancreatic cancer are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Ongoing clinical trials in recurrent pancreatic cancer utilizing irinotecan.

| Number | Name | Phase | Type | Status | Age | Trial IDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A Study of BBI608 (Napabucasin) in Combination With Standard Chemotherapies in Adult Patients With Advanced Gastrointestinal Cancer | Phase II Phase I | Biomarker/laboratory analysis Treatment |

Active | 18 and over | BBI608-246 NCI-2015-00892 NCT02024607 |

| 2 | Bispecific Antibody Armed Activated T-cells With Aldesleukin and Sargramostim in Treating Patients With Locally Advanced or Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer | Phase II Phase I | Biomarker/laboratory analysis Treatment |

Temporarily closed | 18 and over | 2015-100 NCI-2015-01942 1510014428 NCT02620865 |

| 3 | Combination Chemotherapy With or Without Ramucirumab in Treating Patients With Metastatic or Recurrent Pancreatic Cancer | Phase II | Treatment | Active | 18 and over | HCRNGI14-198 NCI-2016-00206 IRB00086601 Winship3142-16 NCT02581215 |

| 4 | FOLFIRI or Modified FOLFIRI and Veliparib as Second-line Therapy in Treating Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer | Phase II | Treatment | Active | 18 and over | S1513 NCI-2015-02248 NCT02890355 |

| 5 | 6,8-bis[benzylthio]octanoic Acid and Combination Chemotherapy in Treating Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer | Phase I | Biomarker/laboratory analysis Tissue collection/repositor Treatment |

Active | 18 and over | CCCWFU #57112 NCI-2013-00674 NCT01835041 |

| 6 | Study of Pembrolizumab With Reolysin® and Chemotherapy in Patients With Advanced Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma | Phase I | Treatment | Active | 18 and over | REO 024 NCI-2015-02218 NCT02620423 |

| 7 | Ascorbic Acid and Combination Chemotherapy in Treating Patients With Locally Advanced or Recurrent Pancreatic Cancer That Cannot Be Removed by Surgery | No phase specified | Treatment | Temporarily closed | 18–75 | 16D.347 NCI-2016-01319 NCT02896907 |

Since irinotecan is a component of FOLFIRINOX, this study can pave the way for its replacement with nanoliposomal irinotecan. However, in light of its expense compared with irinotecan base, liposomal irinotecan/5-FU/folinic acid needs to be compared against established regimens such as FOLFIRI or FOLFIRINOX in the future. Despite the encouraging results seen in NAPOLI-1, the overall survival in MPC continues to remain dismal. From a clinical standpoint, a deeper understanding of pancreatic biology is needed to identify potential molecular targets. Therefore, this remains the mainstay of clinical research in pancreatic cancer.

Furthermore, as more data about specific biomarkers come along in the prediction of treatment response and potential toxicity, we should be able to make evidence-based decisions about its use in more chemotherapeutic regimens. As cancer chemotherapy takes rapid strides in its evolution, this study reiterates the scientific rationale to develop efficient liposome-based drugs. This in turn calls for its trial in the first-line setting of malignancies including but not limited to pancreatic and colorectal cancer. This study also underlines the importance of developing not only more efficacious first-line, but also second-line therapies in MPC. UGT1A1 testing is needed prior to initiation of treatment with nanoliposomal irinotecan since it has a significant impact on dosage modification. As mentioned above, it is recommended that the initial dose be reduced in patients homozygous for the UGT1A1*28 enzyme. In the coming years, further elaboration of nanoliposomal irinotecan toxicities in patients with UGT1A1 gene polymorphisms and other genetic variants is warranted. Moreover, the efficacy of nanoliposomal irinotecan as a component of first-line regimens for advanced pancreatic cancer and in patients previously treated with nongemcitabine-based regimens remains to be assessed.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: MWS has received a grant from Merrimack Pharmaceuticals for research funding. In addition, he has been selected for the Speaker bureau. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Contributor Information

FNU Asad ur Rahman, Internal Medicine Residency, Florida Hospital Orlando, Orlando, FL, USA.

Saeed Ali, Internal Medicine Residency, Florida Hospital Orlando, Orlando, FL, USA.

Muhammad Wasif Saif, Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Oncology and Experimental Therapeutics, Tufts Cancer Center – Tufts Medical Center, 800 Washington Street, Box 245, Boston, MA 02111, USA.

References

- Assaf E., Verlinde-Carvalho M., Delbaldo C., Grenier J., Sellam Z., Pouessel D., et al. (2011) 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin combined with irinotecan and oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX) as second-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Oncology 80: 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns C., Solorzano C., Harbison M., Ozawa S., Tsan R., Fan D., et al. (2000) Blockade of the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling by a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor leads to apoptosis of endothelial cells and therapy of human pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Res 60: 2926–2935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris H., Moore M., Andersen J., Green M., Rothenberg M., Modiano M., et al. (1997) Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 15: 2403–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale J., Ko A. (2016) MM-398 (nanoliposomal irinotecan): emergence of a novel therapy for the treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer. Future Oncol 12: 453–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T., Shiah H., Yang C., Yeh K., Cheng A., Shen B., et al. (2015) Phase I study of nanoliposomal irinotecan (PEP02) in advanced solid tumor patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 75: 579–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L., Li M., Hu J., Ren W., Xie L., Sun Z., et al. (2014) UGT1A1* 6 polymorphisms are correlated with irinotecan-induced toxicity: a system review and meta-analysis in Asians. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 73: 551–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibaudel B., Maindrault-Gœbel F., Bachet J., Louvet C., Khalil A., Dupuis O., et al. (2016) PEPCOL: a GERCOR randomized phase II study of nanoliposomal irinotecan PEP02 (MM-398) or irinotecan with leucovorin/5-fluorouracil as second-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Med 5: 676–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy T., Desseigne F., Ychou M., Bouché O., Guimbaud R., Bécouarn Y., et al. (2011) FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 364: 1817–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crown J., Casper E., Botet J., Murray P., Kelsen D. (1991) Lack of efficacy of high-dose leucovorin and fluorouracil in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 9: 1682–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan S., Moertel C., Wieand H., Schutt A., Krook J., Foley J., et al. (1990) A phase III trial on the therapy of advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Evaluations of the Mallinson regimen and combined 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cisplatin. Cancer 65: 2207–2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCaprio J., Mayer R., Gonin R., Arbuck S. (1991) Fluorouracil and high-dose leucovorin in previously untreated patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: results of a phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 9: 2128–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond D., Noble C., Guo Z., Hong K., Park J., Kirpotin D. (2006) Development of a highly active nanoliposomal irinotecan using a novel intraliposomal stabilization strategy. Cancer Res 66: 3271–3277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-del Castillo C., Tanabe K., Howell D., Director P., Savarese D. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and staging of exocrine pancreatic cancer. 2013. UpToDate (2016) Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and staging of exocrine pancreatic cancer. [http://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-and-nonfamilial-risk-factors-for-exocrine-pancreatic-cancer; accessed 1 November 2016].

- Han J., Lim H., Shin E., Yoo Y., Park Y., Lee J., et al. (2006) Comprehensive analysis of UGT1A polymorphisms predictive for pharmacokinetics and treatment outcome in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with irinotecan and cisplatin. J Clin Oncol 24: 2237–2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan D., Saied A., Kocher H. (2008). Analysis of mortality rates for pancreatic cancer across the world. HPB 10: 58–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A., Bray F., Center M., Ferlay J., Ward E., Forman D. (2011) Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 61: 69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsen D., Hudis C., Niedzwiecki D., Dougherty J., Casper E., Botet J., et al. (1991) A phase III comparison trial of streptozotocin, mitomycin, and 5-fluorouracil with cisplatin, cytosine arabinoside, and caffeine in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer 68: 965–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko A. (2016) Nanomedicine developments in the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer: focus on nanoliposomal irinotecan. Int J Nanomedicine 11: 1225–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko A., Tempero M., Shan Y., Su W., Lin Y., Dito E., et al. (2013) A multinational phase 2 study of nanoliposomal irinotecan sucrosofate (PEP02, MM-398) for patients with gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 109: 920–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Cheng D., Kuang Q., Liu G., Xu W. (2014) Association of UGT1A1* 28 polymorphisms with irinotecan-induced toxicities in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis in Caucasians. Pharmacogenomics J 14: 120–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Siegel R., Jemal A. (2013) Pancreatic cancer death rates by race among US men and women, 1970–2009. J Natl Cancer Inst 105: 1694–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Wang H., Yang Y., Logsdon C., Ullrich S., Hwu P., et al. (2016) Recent advancements in pancreatic cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res Front 2: 252–276. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson C., Rake M., Cocking J., Fox C., Cwynarski M., Diffey B., et al. (1980) Chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer: results of a controlled, prospective, randomised, multicentre trial. Br Med J 281: 1589–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M., Goldstein D., Hamm J., Figer A., Hecht J., Gallinger S., et al. (2007) Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol 25: 1960–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oettle H., Riess H., Stieler J., Heil G., Schwaner I., Seraphin J., et al. (2014) Second-line oxaliplatin, folinic acid, and fluorouracil versus folinic acid and fluorouracil alone for gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer: outcomes from the CONKO-003 trial. J Clin Oncol 32: 2423–2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoue M., Terada T., Kobayashi M., Katsura T., Matsumoto S., Yanagihara K., et al. (2009) UGT1A1* 6 polymorphism is most predictive of severe neutropenia induced by irinotecan in Japanese cancer patients. Int J Clin Oncol 14: 136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passero F., Jr, Grapsa D., Syrigos K., Saif M. (2016) The safety and efficacy of Onivyde (irinotecan liposome injection) for the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer following gemcitabine-based therapy. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 16: 697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelzer U., Schwaner I., Stieler J., Adler M., Seraphin J., Dörken B., et al. (2011) Best supportive care (BSC) versus oxaliplatin, folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil (OFF) plus BSC in patients for second-line advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III-study from the German CONKO-study group. Eur J Cancer 47: 1676–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps M., Sparreboom A. (2014) Irinotecan pharmacogenetics: a finished puzzle? J Clin Oncol 32: 2287–2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip P., Benedetti J., Corless C., Wong R., O’Reilly E., Flynn P., et al. (2010) Phase III study comparing gemcitabine plus cetuximab versus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Southwest Oncology Group-directed intergroup trial S0205. J Clin Oncol 28: 3605–3610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries L., Eisner M., Kosary C., Hankey B., Miller B., Clegg L, et al. (eds) (2002) SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2002. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; [http://seercancergov/Publications/CSR]. [Google Scholar]

- Roy A., Park S., Cunningham D., Kang Y., Chao Y., Chen L , et al. (2013) A randomized phase II study of PEP02 (MM-398), irinotecan or docetaxel as a second-line therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol 24: 1567–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schein P., Lavin P., Moertel C., Frytak S., Hahn R., O’Connell M., et al. (1978) Randomized phase II clinical trial of adriamycin, methotrexate, and actinomycin-D in advanced measurable pancreatic carcinoma: a Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group Report. Cancer 42: 19–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R., Miller K., Jemal A. (2016) Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 66: 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toffoli G., Cecchin E., Corona G., Russo A., Buonadonna A., D’Andrea M., et al. (2006) The role of UGT1A1*28 polymorphism in the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of irinotecan in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 24: 3061–3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ur Rehman S., Lim K., Wang-Gillam A. (2016) Nanoliposomal irinotecan plus fluorouracil and folinic acid: a new treatment option in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 16: 485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rijswijk R., Jeziorski K., Wagener D., Van Laethem J., Reuse S., Baron B., et al. (2004) Weekly high-dose 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid in metastatic pancreatic carcinoma: a phase II study of the EORTC GastroIntestinal Tract Cancer Cooperative Group. Eur J Cancer 40: 2077–2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Hoff D., Ervin T., Arena F., Chiorean E., Infante J., Moore M., et al. (2013) Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med 369: 1691–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang-Gillam A., Li C., Bodoky G., Dean A., Shan Y., Jameson G., et al. (2016) Nanoliposomal irinotecan with fluorouracil and folinic acid in metastatic pancreatic cancer after previous gemcitabine-based therapy (NAPOLI-1): a global, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 387: 545–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Dhakal I., Ning B., Kesteloot H. (2008) Patterns and trends of pancreatic cancer mortality rates in Arkansas, 1969–2002: a comparison with the US population. Eur J Cancer Prev 17: 18–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]