Abstract

Objective:

We explored the concept of design quality in relation to healthcare environments. In addition, we present a taxonomy that illustrates the wide range of terms used in connection with design quality in healthcare.

Background:

High-quality physical environments can promote health and well-being. Developments in healthcare technology and methodology put high demands on the design quality of care environments, coupled with increasing expectations and demands from patients and staff that care environments be person centered, welcoming, and accessible while also supporting privacy and security. In addition, there are demands that decisions about the design of healthcare architecture be based on the best available information from credible research and the evaluation of existing building projects.

Method:

The basic principles of Arksey and O’Malley’s model of scoping review design were used. Data were derived from literature searches in scientific databases. A total of 18 articles and books were found that referred to design quality in a healthcare context.

Results:

Design quality of physical healthcare environments involves three different themes: (i) environmental sustainability and ecological values, (ii) social and cultural interactions and values, and (iii) resilience of the engineering and building construction. Design quality was clarified herein with a definition.

Conclusions:

Awareness of what is considered design quality in relation to healthcare architecture could help to design healthcare environments based on evidence. To operationalize the concept, its definition must be clear and explicit and able to meet the complex needs of the stakeholders in a healthcare context, including patients, staff, and significant others.

Keywords: design quality, evidence-based design, healthcare architecture, hospital design and construction, physical environment

Background

Architecture to promote health and well-being is now considered as an important part of creating a health service of high quality (Clancy, 2008; Sadler et al., 2011). Developments in healthcare technology and methodology put high demands on the design quality of care environments (Bromley, 2012) coupled with increasing expectations and demands from patients and staff that the environments should be person centered, welcoming, and accessible while also supporting privacy and security (Vischer, 2008; Volker, Lauche, Heintz, & de Jonge, 2008). In addition, there are demands that decisions about the design of the healthcare architecture be based on the best available information from credible research and evaluations of existing building projects (Hamilton, 2003; Stankos & Schwarz, 2007; Ulrich, Berry, Quan, & Parish, 2010). Evidence-based design is now an established concept as an approach for quality improvements in the design process of new healthcare architecture (Hamilton & Watkins, 2009). Consequently, it is essential to develop a clear conceptual framework to enable communication and operationalization of what good design stands for and how it can contribute to results in healthcare, rather than relying solely on subjective values about quality. Thus, the concept of design quality has never been so important to emphasize as today. In this article, we explore the concept of design quality in relation to healthcare architecture. In addition, we present a taxonomy based on a scoping review that illustrates the wide range of terms used in connection with design quality of healthcare environments.

Consequently, it is essential to develop a clear conceptual framework to enable communication and operationalization of what good design stands for and how it can contribute to results in healthcare, rather than relying solely on subjective values about quality.

Dictionaries outline design quality as a standard to compare buildings or how good or bad something is rated for it to be considered of good, bad, or top quality. Furthermore, design quality could be a measure of a high standard and the intention of the design (Hornby, Deuter, Bradbery, & Turnbull, 2015; McIntosh, 2013). In architecture, the concept of design quality has been the subject of long-standing theoretical discussion (Volker et al., 2008). From the Roman architect Vitruvius to contemporary design, quality encompasses tangible and intangible properties such as utility, durability, and beauty with a focus on the architect’s own artistic expression (Vitruvius, Dalgren, & Mårtelius, 2009). The concept is multifaceted in that it is linked to both aesthetics and political ideology and more pragmatic requirements such as commissioning specifications and resource limits, while simultaneously subject to the technological and commercial fashions of the day and subjective opinions of what good design should be (Bromley, 2012). Design quality has previously been described as difficult to define and evaluate precisely because it is an imprecise concept that depends on different perspectives and users (Dewulf & Van Meel, 2004; Heylighen & Bianchin, 2013; Volker et al., 2008). One main critique has been that design quality often has been considered from the perspective of the architectural profession (cf. the selection for architectural awards or publications in architectural journals) instead of from the perspectives of those who use the buildings and spaces (Cuff, 1989).

That design quality is difficult to define is often discussed in relation to the observation that a design project can be considered to be a “wicked problem” (Rittel & Webber, 1973); solutions to such problems are neither accurate nor inaccurate; instead, they are good or bad, and better or worse, depending on the perspective from which they are evaluated (Rittel & Webber, 1973). The concept is loaded with philosophical meaning but at the same time is important for the performance of post-occupancy evaluations of new healthcare environments (Gann & Whyte, 2003; Macmillan, 2004). Thus, with the current progress in evidence-based design, there are new demands on the concept to be more precisely defined and communicated to a wide group of interests.

Thus, with the current progress in evidence-based design, there are new demands on the concept to be more precisely defined and communicated to a wide group of interests.

Previous research has implicitly indicated what good design is and how it can be measured. High-quality physical environments can be a therapeutic resource for promoting health and well-being (Evans & McCoy, 1998; Gesler, Bell, Curtis, Hubbard, & Francis, 2004; Nightingale & Goldie, 1997) and as support for the care and treatment of patients (Bromley, 2012; Huisman, Morales, van Hoof, & Kort, 2012; Janssen et al., 2014; R. Ulrich et al., 2008). A well-designed environment with a higher degree of exposure to daylight was found to reduce depression and the treatment time for depressed patients (Benedetti, Colombo, Barbini, Campori, & Smeraldi, 2001). Patients visually exposed to actual or simulated nature may experience relief from pain and have a lower intake of pain-reducing drugs (Malenbaum, Keefe, Williams, Ulrich, & Somers, 2008). Currently, the physical environment is also considered as an integral part of person-centered care defined as thermal comfort, acoustic comfort, and visual comfort for the individual person (Nimlyat & Kandar, 2015; Salonen et al., 2013).

During the last decade, there have also been attempts to develop instruments for assessing design quality, for example, the design quality indicator (DQI; Gann & Whyte, 2003), which focuses on evaluating the complete design and planning phase of new healthcare buildings; the housing quality indicator (Gann, Salter, & Whyte, 2003; Macmillan, 2004), which evaluates housing schemes on the basis of quality; and the Sheffield care environment assessment matrix (Parker et al., 2004) with focus on a comprehensive assessment of the physical environment of residential care facilities. According to the instrument (DQI) developed by Gann and colleagues (2003), design quality can only be achieved when the following three quality domains work together: functionality, building quality, and impact. The three domains identify key aspects of design including access, use, and space, outlined as functionality, and building quality refers to performance and engineering. The impact domain is focused on urban and social integration, the internal environment, form, and materials. Vischer (2008) suggests that the quality of the design should be assessed based not only on users’ (i.e., patients’, significant others’, and staff’s) experiences but also on predetermined quality standards of how the physical healthcare environment should support the target users and activities. However, the quality of physical environments is still evaluated insufficiently because the definitions, attributes, and characteristics of good quality have not been fully understood and communicated (Elf, Engström, & Wijk, 2012).

Inevitably, the question remains How can design quality be defined in relation to healthcare environments? It is an important and timely question that affects decisions about design and also how far the development of research can apply to healthcare environments. Therefore, at a time when evidence-based design efforts increasingly seek out new theories, a better understanding of the concept of design quality is important. The aim of this scoping review was to explore the concept of design quality related to healthcare environments. An additional aim was to discuss the concept of design quality and its relation to evidence-based design.

Method

Design

The basic principles of Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) model for a scoping review design were used. Scoping studies aim to map or summarize a research area, examine the nature of a topic, or identify research gaps in the existing literature where a subject or research area is complex and underexplored. In this review, the purpose was to summarize how a concept (design quality) is understood and used in a particular area (physical healthcare environment e.g. architecture and built environment). Based on the review, we developed a taxonomy that illustrates the wide range of terms used in relation to design quality in healthcare.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To fulfil the purpose of this review, the included literature was required to (i) address the concept design quality, (ii) describe design quality in the context of the healthcare sector, and (iii) be published in English or a Nordic language. To evaluate all uses of the concept, all types of peer review papers and articles were included (theoretical, editorial, original articles, discussion drafts, and reviews). Furthermore, to widen data collection, the study included gray literature (such as thesis and book chapters) to find all uses of design quality in healthcare contexts.

Search Strategy

An extensive systematic literature search was conducted, reflecting all uses of the concept of design quality in a healthcare context. A systematic database search of peer-reviewed papers was conducted in the Avery Index to Architectural Periodicals, CINAHL, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science combining key words pertaining to healthcare, physical environment, and design quality (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key Words Used in the Literature Search.

| All Words Related to Design | All Words Related to Physical Environment | All Words Related to Healthcare |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Data Extraction and Critical Appraisal

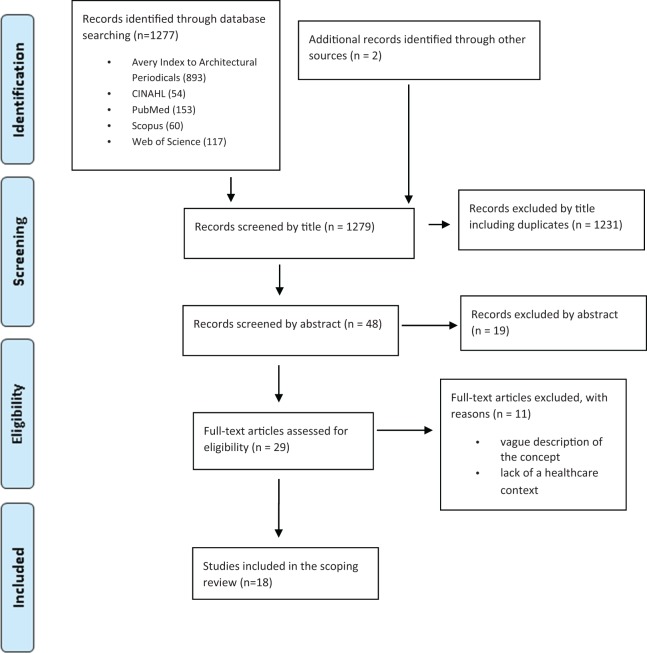

The database search resulted in 1,279 titles, including gray literature from Libris (the Swedish libraries search service). All titles were screened, and 48 abstracts were identified in the initial review. After the abstracts had been read, it was determined that 29 full-text articles would be assessed for eligibility. Eleven articles were excluded because they failed to meet the inclusion criteria specified above. Eighteen studies were included in the review. A flowchart of the search is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow diagram of the screening process of the literature.

Analysis Method

Thematic synthesis was performed according to the method described by Gough, Oliver, and Thomas (2012). Thematic synthesis has two stages: (i) coding text and (ii) developing descriptive themes. For this review, the publications were sorted based on the way they used the concept of design quality. To structure and gather how publications used the concept of design quality, selected texts reflecting the views and descriptions of the concept of design quality in a healthcare context were organized in a matrix in which the texts were grouped together and coded (Table 2). General characteristics of the included literature organized into descriptive themes are outlined in Table 3. The focus of the analysis was to identify and describe codes that reflected how the concept was described in the literature. Thus, the purpose of encoding was to bring out the essence of the texts that illustrated the use of the concept of design quality. The codes were put into a taxonomic structure grouped into three different descriptive themes (Figure 2). The hierarchy of the taxonomy was that the strongest and most prominent attribute (1, 2, 3) to each theme came first, followed by secondary attributes (a, b, c).

Table 2.

Examples of Quotations from the Text, Codes, and Themes.

| Literature | Quotations | Codes | Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orr (1994) Design quality; designing for the human side of healthcare. | “the influence of building design quality on the people using it is irreducible from the social context of that environment” | Participation Social value | Social and cultural interactions and values |

| Giddings, Sharma, Jones, and Jensen (2013) An evaluation tool for design quality: PFI sheltered housing | “design categories e.g. building forms, scale, arrangement, volumes, corridors, acoustics” | Scale Usability | Resilience of engineering and building construction |

Note. PFI = private finance initiative.

Table 3.

General Characteristics of the Included Literature Organized in Descriptive Themes.

| Themes | Literature | Quotations From Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental sustainability and ecological values Social and cultural interactions and values Resilience of engineering and building construction | Castro, Mateus, and Braganca. (2013a). Improving sustainability in healthcare with better space design quality, Boca Raton, CRC Press–Taylor & Francis Group Delaney and Burnett. (1994). Design quality: Landscape design—improving the quality of healthcare. Journal of healthcare design Bilec et al. (2009). Analysis of the design process of green children’s hospitals. Journal of Green Building Orr. (1994). The nature of design; ecology, culture and human intention Stern et al. (2003). Understanding the consumer perspective to improve design quality. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research Orr. (1994). Design quality; designing for the human side of healthcare. Journal of healthcare design Watson, Evans, Karvonen, & Whitley. (2014). Re-conceiving building design quality: A review of building users in their social context. Indoor and Built Environment Fornara, Bonaiuto, and Bonnes. (2006). Perceived hospital environment quality indicators: A study of orthopaedic units. Journal of Environmental Psychology Thomson, O’Keeffe, and Dainty. (2011). Beyond scoring: Facilitating enhanced evaluation of the design quality of National Health Service (NHS) healthcare buildings Bobrow and Van Gelder. (1980). The well-being of design quality in the health-care world. Architectural Record Castro et al. (2013c). Indoor and outdoor spaces design quality and its contribution to sustainable hospital buildings. Green Design, Materials and Manufacturing Processes Battles. (2006). Quality and safety by design. Quality and Safety in Health Care Giddings, Sharma, Jones, and Jensen. (2013). An evaluation tool for design quality: PFI sheltered housing Freihoefer, Nyberg, & Vickery. (2013). clinic exam room design: Present and future. HERD | “Eco-humanism in architecture is about having an equal concerns for human and ecological wellbeing” “A window wall creates an opportunity for patients to view the garden./---/ the sights of the garden can be brought indoors in the atrium or the winter garden.” “protecting the health of the surrounding community, protecting the health of the larger global community” “Ecological design is an art by which we aim to restore and maintain the wholeness of the entire fabric of life” “design should be a symbol of a culture of healing, health, caring, and compassion” “the influence of building design quality on the people using it is irreducible from the social context of that environment” “more human designs are important contributors to patient psychological and physical health” “to understand the social interactions of the projects stakeholders whilst they use the prescribed instruments” “the concerns about the quality of space and about a buildings relationship to its context and community have become stronger” “the design is definitely becoming, not less patient-centered. The concerns about a building's relationship to its context and community have become stronger” “so it is important to encourage the architects to incorporate these concerns in their projects, avoiding solving future problems with the addition of equipment or other solutions that increase energy consumption, water, or other resources” “the care delivery system must be resilient enough to prevent human errors or system failures to have an adverse impact on patient /---/effective, timely, efficient, and equitable” “design categories e.g building forms, scale, arrangement, volumes, corridors, acoustics” “Specific design qualities discussed include overall size, location of doors and privacy curtains, positioning of exam tables, influence of technology in the consultation area, types of seating, and placement of sink and hand sanitizing dispensers.” |

| Overlapping Literature; Environmental Sustainability and Values, Social and Cultural Values, and Resilience of Engineering and Building Construction | ||

| Castro et al. (2013b). Space design quality and its importance to sustainable construction: The case of hospital buildings. Portugal SB13-contribution of sustainable building to meet EU 20-20-20 targets. “The proposal is to divide criteria in three dimensions (environmental, social and functional, and economical) and incorporate the indoor and outdoor spaces design quality especially in the sociocultural and functional quality category” | ||

| Design Quality Indicator for Health. (2015). Construction Industry Council, London. “Design quality outlined as build quality (construction, engineering), functionality (access, space, use), and impact (form, materials, urban and social integration.” | ||

| Gesler et al. (2004). Therapy by design: Evaluating the UK hospital building program. Health and Place. “Environments must be considered as physical environments (both natural and built), social environments and symbolic environments” | ||

| Phiri. (2014). Health Building Note 00-01 General design guidance for healthcare buildings. Department of Health, UK gov. “excellence design quality /---/ integrate functionality (use, access and space), impact (character and innovation, form and materials, patient environment, urban and social integration) and build quality (performance, engineering and construction)” | ||

Figure 2.

The taxonomy of codes pertaining to design quality in the context of healthcare.

|

A. ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY AND ECOLOGICAL VALUES

B. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL INTERACTIONS AND VALUES

C. RESILIENCE OF ENGINEERING AND BUILDING CONSTRUCTION

|

|

|

Results

Based on the analysis of the selected literature, the usage of the concept of design quality in a healthcare context can be characterized by three different descriptive themes: (i) environmental sustainability and ecological values, (ii) social and cultural interactions and values, and (iii) resilience of engineering and building construction. These three themes are all part of how the current literature uses the concept in a healthcare perspective. The three themes are not isolated from each other; rather, they interlink and reflect the broad usage of the concept design quality. These themes are detailed and presented in a taxonomic structure (Figure 2). The themes are presented and discussed below using quotations from the literature illustrating the taxonomy of codes pertaining to design quality in the context of healthcare.

Environmental Sustainability and Ecological Values

The first identified theme relates to environmental sustainability and ecological values. This theme incorporates concepts such as sustainable design, “green” design, and green principles (Figure 2). These quality aspects mostly relate to the room’s ability to connect people in the building with the environment beyond the physical walls. For example, a sustainable environment should be related to the surrounding community while simultaneously bringing the occupants closer to the natural elements (Delaney & Burnett, 1994; Phiri, 2014).

The included literature also discussed design quality in relation to ecological values. For example, Castro, Mateus, and Braganca (2013a) highlight eco-humanism in architecture and propose that architecture must be equally concerned with human and ecological well-being, a responsibility that is 2-fold. According to Orr (1994) and Bilec et al. (2009), design quality is a question of how the environment influences and is related to the immediately surrounding community and also a wider global ecological perspective. The authors stated that when designing a healthcare environment, the designer is constantly responsible to the immediate society as well as to a larger global community. Ecological responsibility means that healthcare buildings need to be designed with respect for nature. Furthermore, the results of the review showed that nature is seen to play an equally important part in human needs and desires, and as a consequence, architects or designers planning a new healthcare environment need to be aware of both people and nature when designing a healthcare building: “Eco-humanism in architecture is about having an equal concern for human and ecological wellbeing” (Castro et al., 2013a, p. 4).

Another concept that was included in the taxonomy was green design (Figure 2). Green design is an expression of the desire to create a hospital that addresses the necessity of creating healing healthcare environments, and the building materials must be based on renewable materials and environmentally friendly energy, such as solar panels on the roof, which is becoming an increasingly important aspect of design quality (Bilec et al., 2009; Castro et al., 2013a; Design Quality Indicator for Health, 2015).

Social and Cultural Interactions and Values

The second identified theme concerns social and cultural interactions and values (Figure 2). This theme includes social responsibility. Castro et al. (2013b) propose “to divide criteria in three dimensions (environmental, social and functional, and economical) and incorporate the indoor and outdoor space design quality especially in sociocultural and functional quality category” (Castro et al., 2013b. p. 419). In healthcare contexts, social responsibility includes both the patient and the professional: “The influence of building design quality on the people using it is irreducible from the social context of building users” (Watson, Evans, Karvonen, & Whitley, 2014, p. 2) and “addresses the impact of hospital and ward design on the healthcare professionals working in the space” (Watson et al., 2014, p. 6).

Several of the included publications argue that new physical healthcare environments outline accountability toward humans and their social contexts as central when using the concept of design quality. Accountability considers the different cultural aspects of a country, such as religion and ethical values, as well as those created in a social context that architects or designers must relate to when designing a healthcare environment (Orr, 1994; Stern et al., 2003).

To illustrate this further, several of the included publications describe the core concern for design quality as the ability to support human needs and underline that the architecture should incorporate signs that show an awareness of social values, for example, respect, dignity, and humanization. Several of the included articles refer to social interactions as a bridge from the healthcare environment to the surrounding community (Castro et al., 2013b; Thomson, O’Keeffe, & Dainty, 2011; Watson et al., 2014).

Well-being and stress reduction are both social and cultural interpretations of what makes for an efficient and therapeutic healthcare setting (Bobrow & Van Gelder, 1980; Gesler et al., 2004). Fornara, Bonaiuto, and Bonnes (2006) describe supportive design as a way of promoting wellness and reducing stress and even as part of effective communication.

Resilience of Engineering and Building Construction

The last theme concerns the resilience of engineering and built construction. The central concepts in this theme are security, efficiency, scale, and usability (Figure 2). Some of the included literature argues that one of the main purposes of the physical healthcare environment is to be safe and secure. Additionally, air quality and ventilation, an optimized water system, and nonslippery floor coverings are some of the aspects architects and designers need to consider in the planning and design process (Battles, 2006; Gesler et al., 2004; Healthcare, 2015). Battles (2006) argues that a healthcare building must be effective and efficient to be considered to be of top quality. Furthermore, “The care delivery system must be resilient enough to prevent human errors or system failures to have an adverse impact on patient” (p. 1).

However, a central part of design quality is expressed as the building form, internal and external space, and architectural components such as building envelope, external doors and windows, use of space and adaptability, and influence of technology in the consultation area (Freihoefer, Nyberg, & Vickery, 2013; Giddings, Sharma, Jones, & Jensen, 2013).

As part of the taxonomy, an important aspect of design quality is the concept of flexibility. A future change in care activities should not automatically necessitate new construction, and a flexible design at an early stage reduces the need for further improvements and shall be reflected in all building documents in the form of built-in flexibility (Castro et al., 2013c; Phiri, 2014).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the first articles to explore the concept of design quality in relation to healthcare environments. The review resulted in a taxonomy that contains themes and a wide range of terms used in the literature that consider design quality in healthcare environments. These themes together provide a picture of how the concept of design quality is used in the literature. The themes are not necessarily isolated from each other; rather, they are all part of how researchers, architects, and designers within the field of healthcare architecture use the concept when they write about design quality. The results suggest that the concept covers three main themes: environmental sustainability and ecological values, social and cultural interaction and values, and the resilience of engineering and building construction (Figure 2).

It is not surprising that the environmental sustainability and ecological aspects of design quality are emphasized in the literature. Recently, sustainability has become one of the main goals of healthcare (Costello et al., 2009; Woodward et al., 2014), including sustainable healthcare buildings (Ryan-Fogarty, O’Regan, & Moles, 2016; Unger, Campion, Bilec, & Landis, 2016). The most basic sustainability concept adopts an ecological approach, which involves reducing the consumption of natural resources (Costanza & Daly, 1992), and development in healthcare should maintain an environment that does not harm the health of present or future generations (Anåker & Elf, 2014). Sustainable development must integrate not only environmental goals but also social and economic components (Brundtland et al., 1987). In the present review, sustainability in relation to design quality was approached in a holistic way, in which environmental considerations included the nearest community but also a global perspective (Delaney & Burnett, 1994; Orr, 1994). Although several studies included in the review used the concept of sustainability, it was mentioned in an abstract and in a nonspecific way. This will soon change because many new instruments, such as LEED, assess the sustainability of buildings (Azhar, Carlton, Olsen, & Ahmad, 2011) as a way of more closely defining design quality in relation to sustainability. A focus on sustainability in relation to healthcare architecture is a promising development, although still a new area of research with few published studies. Sustainable development must be integrated into all levels within a healthcare organization, including the physical environment (Costello et al., 2009; Woodward et al., 2014). Collaboration between representatives from healthcare organizations, planners, and architects, and also researchers, is required, and the concept of design quality in relation to sustainable healthcare environments must be made explicit.

Collaboration between representatives from healthcare organizations, planners, and architects, and also researchers, is required, and the concept of design quality in relation to sustainable healthcare environments must be made explicit.

Social and cultural interactions and values are other features of design quality mentioned in the literature. The argument in many articles was that quality can be obtained if the buildings are connected to the society, its culture, and its values. A common argument was that a care environment must be resistant to rapid change and must be able to manage the needs of various users (patients, relatives, and staff). This includes an environment that is humane, supports well-being, and has respect for different social and cultural values. The main idea is that the environment should be resilient to future changes while retaining essentially the same function, structure, and identity (Walker, Holling, Carpenter, & Kinzig, 2004; Weller, 2014). Walker (2004) described resilience as a persistent system able to absorb disruptions and reorganizations and the ability to cope with change. However, as mentioned above, social and cultural interactions and values need to be defined to communicate the meaning of these concepts.

Several articles included in the review used the concept of design quality in relation to engineering and the built structure. In these articles, the authors focused on the structure or environment, functionality, and technical design details. For example, important and common attributes mentioned include building safety, such as the shape of the windows, and also the function and structure of materials, such as the use of nonslippery floors. The technical and engineering aspects are indeed important, and this area seems to be the most complete in terms of defining quality, mainly because it is fairly easy and straightforward to objectively define and measure these aspects.

There is still a need to define quality in relation to technology. For example, safety needs to be defined in relation to different contexts. A safe environment can have different meanings and different importance depending on whether the healthcare environment is, for example, a stroke care unit or a healthcare facility for older people. Health services designed with a great emphasis on safety may result in lower well-being of patients (Nimlyat & Kandar, 2015; Salonen et al., 2013). Thus, safety in a stroke care unit means that an interprofessional team can perform rigorous observations and assessments early in the stroke disease process (Langhorne, 2014). In a healthcare environment for older people, increased environmental safety can mean a reduction in autonomy as too much protection may prevent the older person from moving freely within the environment (Nordin, McKee, Wijk, & Elf, 2016).

We noticed that the concept of design quality continues to evolve and has shifted from exclusively a subject’s idea of what constitutes a beautiful building to a concept with many related terms and a whole literature base. However, there is still a tendency to use the term in a vague manner, and outcome measures are rare. In most cases, the term is only briefly described.

This is problematic because design quality is no longer a concept that can be isolated from the movement of evidence-based design. Rather, a better articulation of what we mean by design quality is needed for developing and maintaining evidence-based design. Because of the concept’s ambiguity and lack of clarity in healthcare architecture, it is impossible to operationalize aspects of design quality in a specific way. Without clear definitions and an understanding of design quality, it will be quite challenging to develop theories.

…design quality is no longer a concept that can be isolated from the movement of evidence-based design

How can we define the concept of design quality based on this review? The closest definition that can be formulated is as follows: “Design quality in a healthcare context can be defined from a set of core attributes, including environmental sustainability, social interaction, and cultural values. Additionally, resilience of engineering and building construction is fundamental to the design quality of healthcare environments. The implementation of design quality will contribute to resilient decision-making in the architecture of physical healthcare environments by the use of evidence-based design.” This definition is a first step to understanding how design quality can be considered in the design of new healthcare environments. The themes and taxonomy can be considered as a framework to guide the planning and design process and research. However, we have a long way to go before the terms in the presented taxonomy can be communicated, operationalized, and used in practice.

To be operationalized, the concept must be clear and explicit and able to meet the complex needs of the stakeholders in a healthcare context, including patients, staff, and significant others. In addition, this review showed that the descriptions and usage of design quality emphasize the social and cultural interaction and environmental sustainability. There seems to be a contradiction between how the concepts are used in the literature and the most common way to measure design quality in completed buildings, which often is focused on functional and technical aspects.

Strengths and Limitations

This scoping review is based on a wide variety of literature (theoretical, editorial, original articles, discussion drafts, and reviews) and searches in the most common health and architecture databases, which strengthens its validity (Gough, Oliver, & Thomas, 2012). To minimize the risk of bias in the analysis, the authors had ongoing discussions with each other and with colleagues in different research areas, such as nursing, architecture, and medical science. Although our search was systematic and allowed us to identify publications that address the concept of design quality in healthcare, there were some limitations to our approach. First, searching for publications in the “gray area” such as reference lists of already included publications and books might have precluded the inclusion of more recent articles in our scoping review. Nevertheless, we have included publications as recently as 2015. Second, we did not appraise the quality of the publications according to the method of a scoping review. Using a scoping review, we were able to identify the extent of the use of the concept of design quality to a wide range of aims and strategies.

Conclusion

Evidence-based design is an emerging concept in relation to healthcare facilities. In most studies, even when the concept of design quality is mentioned, only vague descriptions are used. However, the studies included in this review had a focus on environmental sustainability, social and cultural interactions, and resilient construction. Design quality is outlined as a core concept in the development of new healthcare environments. Therefore, we can assume that early awareness of what design quality is or can be in a healthcare context could help to design healthcare environments based on evidence.

…we can assume that early awareness of what design quality is or can be in a healthcare context could help to design healthcare environments based on evidence.

We need researchers to produce data about the construction of new healthcare environments and to ultimately provide important knowledge about how good design in the healthcare sector is defined. Further research must therefore evaluate sustainability, social or cultural values, and the feasible functionality of a physical healthcare environment with the aim of incorporating the new knowledge into the actual design of a healthcare building.

Implications for Practice

Explicit definitions of design quality could help to create a design that is evidence based.

To be useful, the concept of design quality needs to be connected to quality indicators of healthcare.

A clear and explicit definition and understanding of design quality could help stakeholders in healthcare contexts, including patients, staff, and significant others, to understand how good design could be manifested in a healthcare context.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, Design_Quality_in_the_Context_of_Healthcare_Environments for Design Quality in the Context of Healthcare Environments: A Scoping Review by Anna Anåker, Ann Heylighen, Susanna Nordin, Marie Elf in HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors would like to thank Dalarna University and the research area Health and Welfare for financial support.

References

- Anåker A., Elf M. (2014). Sustainability in nursing: a concept analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 28, 381–389. doi:10.1111/scs.12121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Azhar S., Carlton W. A., Olsen D., Ahmad I. (2011). Building information modeling for sustainable design and LEED® rating analysis. Automation in Construction, 20, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Battles J. B. (2006). Quality and safety by design. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 15, i1–i3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti F., Colombo C., Barbini B., Campori E., Smeraldi E. (2001). Morning sunlight reduces length of hospitalization in bipolar depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 62, 221–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilec M., Ries R., Needy K., Gokhan M., Phelps A., Enache-Pommer E.,…McGregor E. (2009). Analysis of the design process of green children’s hospitals: Focus on process modeling and lessons learned. Journal of Green Building, 4, 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bobrow M., Van Gelder P. (1980). The well-being of design quality in the health-care world. Architectural Record, 167, 107–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley E. (2012). Building patient-centeredness: Hospital design as an interpretive act. Social Science and Medicine, 75, 1057–1066. doi:doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland G., Khalid M., Agnelli S., Al-Athel S., Chidzero B., Fadika L.…Others A. (1987). Our common future (‘Brundtland report’). Our common future (‘Brundtland report’). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castro M., Mateus R., Braganca L. (2013. a). Improving sustainability in healthcare with better space design quality. Green Design, Materials and Manufacturing Processes, 2013, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Castro M., Mateus R., Braganca L. (2013. b). Space design quality and its importance to sustainable construction: The case of hospital buildings In Braganca L., Nateus R., Pinheiro M. (Eds.), Portugal SB13: Contribution of sustainable building to meet EU 20-20-20 targets (pp. 413–420). Braga, Portugal: Universidad do Minho. [Google Scholar]

- Castro M., Mateus R., Braganca L. (2013. c). Indoor and outdoors spaces design quality and its contribution to sustainable hospital buildings. Central Europe towards Sustainable Buildings, 2013, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Clancy C. M. (2008). Designing for safety: Evidence-based design and hospitals. American Journal of Medical Quality, 23, 66–69. doi:10.1177/1062860607311034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanza R., Daly H. E. (1992). Natural Capital and Sustainable Development. Conservation Biology, 6, 37–46. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1992.610037.x [Google Scholar]

- Costello A., Abbas M., Allen A., Ball S., Bell S., Bellamy R.,…Patterson C. (2009). Managing the health effects of climate change. The Lancet, 373, 1693–1733. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60935-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuff D. (1989). The social production of built form. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 7, 433–447. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney C., Burnett J. D. (1994). Design quality: Landscape design—Improving the quality of healthcare. Journal of Healthcare Design: Proceedings from The Symposium On Healthcare Design. Symposium on Healthcare Design, 6, 153–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Design Quality Indicator for Health. (2015). Retrieved from http://www.dqi.org.uk/case-studies/healthcare/

- Dewulf G., Van Meel J. (2004). Sense and nonsense of measuring design quality. Building Research & Information, 32, 247–250. [Google Scholar]

- Elf M., Engström M. S., Wijk H. (2012). Development of the Content and Quality in Briefs Instrument (CQB-I). Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 5(3), 74–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans G. W., McCoy J. M. (1998). When buildings don’t work: The role of architecture in human health. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 18, 85–94. doi:10.1006/jevp.1998.0089 [Google Scholar]

- Fornara F., Bonaiuto M., Bonnes M. (2006). Perceived hospital environment quality indicators: A study of orthopaedic units. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 26, 321–334. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.07.003 [Google Scholar]

- Freihoefer K., Nyberg G., Vickery C. (2013). Clinic exam room design: Present and future. Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 6(3), 138–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gann D., Salter A., Whyte J. (2003). Design quality indicator as a tool for thinking. Building Research & Information, 31, 318–333. doi:10.1080/0961321032000107564 [Google Scholar]

- Gann D., Whyte J. (2003). Design quality, its measurement and management in the built environment. Building Research & Information, 31, 314–317. [Google Scholar]

- Gesler W., Bell M., Curtis S., Hubbard p., Francis S. (2004). Therapy by design: Evaluating the UK hospital building program. Health Place, 10, 117–128. doi:10.1016/s1353-8292(03)00052-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giddings B., Sharma M., Jones P., Jensen P. (2013). An evaluation tool for design quality: PFI sheltered housing. Building Research & Information, 41, 690–705. [Google Scholar]

- Gough D., Oliver S., Thomas J. (2012). An introduction to systematic reviews. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton D. K. (2003). The four levels of evidence-based practice. Healthcare Design, 3, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton D. K., Watkins D. H. (2009). Evidence-based design for multiple building types. New York: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Heylighen A., Bianchin M. (2013). How does inclusive design relate to good design? Designing as a deliberative enterprise. Design Studies, 34, 93–110. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2012.05.002 [Google Scholar]

- Hornby A. S., Deuter M., Bradbery J., Turnbull J. (2015). Oxford advanced learner’s dictionary of current English. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huisman E. R. C. M., Morales E., van Hoof J., Kort H. S. M. (2012). Healing environment: A review of the impact of physical environmental factors on users. Building and Environment, 58, 70–80. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2012.06.016 [Google Scholar]

- Janssen H., Ada L., Bernhardt J., McElduff P., Pollack M., Nilsson M., Spratt N. J. (2014). An enriched environment increases activity in stroke patients undergoing rehabilitation in a mixed rehabilitation unit: A pilot non-randomized controlled trial. Disability & Rehabilitation, 36, 255–262. doi:10.3109/09638288.2013.788218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhorne P. (2014). Organized inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke. Stroke, 45, e14–e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan S. (2004). Designing better buildings: Quality and value in the built environment. London, England: Spon. [Google Scholar]

- Malenbaum S., Keefe F. J., Williams A., Ulrich R., Somers T. J. (2008). Pain in its environmental context: Implications for designing environments to enhance pain control. Pain, 134, 241–244. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2007.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh C. (2013). Cambridge advanced learner’s dictionary. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale F., Goldie S. M. (1997). Florence Nightingale: Letters from the Crimea 1854-1856. Manchester, England: Mandolin. [Google Scholar]

- Nimlyat P. S., Kandar M. Z. (2015). Appraisal of indoor environmental quality (IEQ) in healthcare facilities: A literature review. Sustainable Cities and Society, 17, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Nordin S., McKee K., Wijk H., Elf M. (2016). Exploring environmental variation in residential care facilities for older people. Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 10(2), 49–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr R. (1994). Design quality: Designing for the human side of healthcare. Journal of Healthcare Design: Proceedings From The Symposium on Healthcare Design. Symposium on Healthcare Design, 6, 163–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker C., Barnes S., McKee K., Morgan K., Torrington J., Tregenza P. (2004). Quality of life and building design in residential and nursing homes for older people. Ageing & Society, 24, 941–962. [Google Scholar]

- Phiri M. (2014). Health Building Note 00-01 General design guidance for healthcare buildings. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/316247/HBN_00-01-2.pdf

- Rittel H. W., Webber M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy sciences, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan-Fogarty Y., O’Regan B., Moles R. (2016). Greening healthcare: Systematic implementation of environmental programmes in a university teaching hospital. Journal of Cleaner Production, 126, 248–259. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.03.079 [Google Scholar]

- Sadler B. L., Berry L. L., Guenther R., Hamilton D. K., Hessler F. A., Merritt C., Parker D. (2011). Fable hospital 2.0: The business case for building better health care facilities. Hastings Center Report, 41, 13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonen H., Lahtinen M., Lappalainen S., Nevala N., Knibbs L. D., Morawska L., Reijula K. (2013). Design approaches for promoting beneficial indoor environments in healthcare facilities: A review. Intelligent Buildings International, 5, 26–50. [Google Scholar]

- Stankos M., Schwarz B. (2007). Evidence-based design in healthcare: A theoretical dilemma. Interdisciplinary Design and Research e-Journal, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Stern A. L., MacRae S., Gerteis M., Harrison T., Fowler E., Edgman-Levitan S.,…Ruga W. (2003). Understanding the consumer perspective to improve design quality. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 20, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson D. S., O’Keeffe D., Dainty A. R. (2011). Beyond scoring: Facilitating enhanced evaluation of the design quality of NHS healthcare buildings. In Proceedings of the 4th Annual Conference of the Health and Care Infrastructure Research and Innovation Centre, HaCIRC 2011. Global Health Infrastructure—Challenges for the next Decade, September 26–28, 2011, Manchester (pp. 66–82). London, UK: The Health and Care Infrastructure Research and Innovation Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich R. S., Berry L. L., Quan X., Parish J. T. (2010). A conceptual framework for the domain of evidence-based design. Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 4(1), 95–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich R. S., Zimring C., Zhu X., DuBose J., Seo H. B., Choi Y. S. (2008). A review of the research literature on evidence-based health-care design. Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 1(3), 61–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger S. R., Campion N., Bilec M. M., Landis A. E. (2016). Evaluating quantifiable metrics for hospital green checklists. Journal of Cleaner Production, 127, 134–142. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.03.167 [Google Scholar]

- Walker B., Holling C. S., Carpenter S. R., Kinzig A. (2004). Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecology and society, 9, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Watson K. J., Evans J., Karvonen A., Whitley T. (2014). Re-conceiving building design quality: A review of building users in their social context. Indoor and Built Environment, doi:1420326X14557550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller M. (2014). The battle for open: How openness won and why it doesn’t feel like victory. London, England: Ubiquity. [Google Scholar]

- Vischer. (2008). Towards an environmental psychology of workspace: how people are affected by environments for work. Architectural Science Review, 51, 97–108. doi:10.3763/asre.2008.5114 [Google Scholar]

- Vitruvius M., Dalgren B., Mårtelius J. (2009). Om arkitektur: tio böcker. Stockholm, Sweden: Dymling. [Google Scholar]

- Volker L., Lauche K., Heintz J. L., de Jonge H. (2008). Deciding about design quality: Design perception during a European tendering procedure. Design Studies, 29, 387–409. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2008.03.004 [Google Scholar]

- Walker B., Holling C. S., Carpenter S. R., Kinzig A. (2004). Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 9, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward A., Smith K. R., Campbell-Lendrum D., Chadee D. D., Honda Y., Liu Q.,…Haines A. (2014). Climate change and health: On the latest IPCC report. Lancet, 383, 1185–1189. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60576-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, Design_Quality_in_the_Context_of_Healthcare_Environments for Design Quality in the Context of Healthcare Environments: A Scoping Review by Anna Anåker, Ann Heylighen, Susanna Nordin, Marie Elf in HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal