Abstract

The cellular prion protein (PrPC) has been extensively studied because of its pivotal role in prion diseases; however, its functions remain incompletely understood. A unique line of goats has been identified that carries a nonsense mutation that abolishes synthesis of PrPC. In these animals, the PrP-encoding mRNA is rapidly degraded. Goats without PrPC are valuable in re-addressing loss-of-function phenotypes observed in Prnp knockout mice. As PrPC has been ascribed various roles in immune cells, we analyzed transcriptomic responses to loss of PrPC in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from normal goat kids (n = 8, PRNP+/+) and goat kids without PrPC (n = 8, PRNPTer/Ter) by mRNA sequencing. PBMCs normally express moderate levels of PrPC. The vast majority of genes were similarly expressed in the two groups. However, a curated list of 86 differentially expressed genes delineated the two genotypes. About 70% of these were classified as interferon-responsive genes. In goats without PrPC, the majority of type I interferon-responsive genes were in a primed, modestly upregulated state, with fold changes ranging from 1.4 to 3.7. Among these were ISG15, DDX58 (RIG-1), MX1, MX2, OAS1, OAS2 and DRAM1, all of which have important roles in pathogen defense, cell proliferation, apoptosis, immunomodulation and DNA damage response. Our data suggest that PrPC contributes to the fine-tuning of resting state PBMCs expression level of type I interferon-responsive genes. The molecular mechanism by which this is achieved will be an important topic for further research into PrPC physiology.

Introduction

The cellular prion protein (PrPC) can misfold into disease-provoking conformers (PrP scrapie; PrPSc) that give rise to several neurodegenerative prion diseases, such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) in humans, scrapie in sheep and goats, and bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cattle [1]. The seeding of PrPSc in brain tissue acts as a template for further misfolding of PrPC, ultimately leading to severe neurodegeneration and neuronal death [1].

PrPC is abundant throughout the nervous system, and, albeit at lower levels, in most other tissues of the body [2]. The protein is conserved in mammalian species [3, 4] and expressed already during early embryonal stages [5]. It was therefore surprising that Prnp0/0 mice developed normally and revealed no major phenotypes besides being prion-disease resistant [6–8]. Interestingly, in four Prnp0/0 mouse models (Ngsk, Rcm0, ZrchII, and Rikn), ablation of the Prnp gene induced severe degeneration of cerebellar Purkinje neurons [9–12]. This was, however, subsequently shown to be caused by ectopic expression of the prion-like protein Doppel (Dpl) in the brain, as a side-effect of the transgenic protocols [10]. Two additional Prnp-ablated mouse lines (ZrchI and Npu) displayed no neurodegeneration [7, 8]. Furthermore, other experiments have shown that a polymorphism in another Prnp flanking gene, Sirp-alpha, could significantly influence the interpretation of data that concerns the roles for PrPC in phagocytosis [13]. Despite these inherent challenges with Prnp-null models [14], collectively known as the flanking-gene problem, the Prnp0/0 lines have proven extremely valuable in exploring PrPC physiology. They have provided clues regarding maintenance of axonal myelin [15–17], modulation of circadian rhythms [18], and neuronal excitability [19], in addition to protective roles in severe stress such as ischemia [20] and hypoxic brain damage [21].

A more general problem is the gap between mice and human physiologies [22–24]. The two species diverged about 65 million years ago, and differ substantially in both size and life span. Mice have evolved into short-lived animals relying on massive reproductive capacity, whereas humans reside at the other end of the spectrum, with low reproduction rates and life spans of approximately 80 years. This is of particular significance in modeling chronic human diseases that take decades to develop, and often involve subtle immunological imbalances [22]. In addition, translation to human medicine has proven challenging.

Recently, we identified what seems to be a unique line of dairy goats carrying a nonsense mutation that completely abolishes synthesis of PrPC [25]. This spontaneous, non-transgenic model, is referred to as PRNPTer/Ter. Approximately 10 percent of the Norwegian dairy goat population carries the mutated allele. These animals appear to have normal fertility and behavior in all aspects of standard husbandry. We have no data to suggest that they are over-represented in disease statistics or otherwise failing in production performance. Careful analysis of hematological and blood biochemical parameters, as well as basic immunological features, did not reveal any abnormalities [26]. It was, however, noted that goats without PrPC had slightly elevated numbers of red blood cells, identical to an observation in transgenic cattle without PrPC [27], suggesting that this is a true biological loss-of-function phenotype, at least in ruminants.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) express moderate, but dynamic, levels of PrPC [28]. We observed that goats heterozygous for the mutation (PRNP+/Ter) express half the amount of cell surface PrPC on PBMCs [26]; however, a 50 percent reduction in levels compared to PBMCs from PRNP+/+ goats did not stimulate compensatory expression from the normal allele. Intrigued by this, and the fact that many reports have pointed to putative functions for PrPC in immune cells (reviewed in [29], [30, 31]), mRNA sequencing of PBMCs derived from normal goats and goats without PrPC was performed. The main goal of this study was to evaluate whether the loss of PrPC elicits a transcriptional response in PBMCs that could reveal biological processes involving PrPC. Our findings show that in the absence of PrPC, a subtle, but highly significant change in the transcriptional profile of PBMCs is seen, dominated by upregulation in the expression of type I interferon-responsive genes.

Results

RNA-seq data quality control

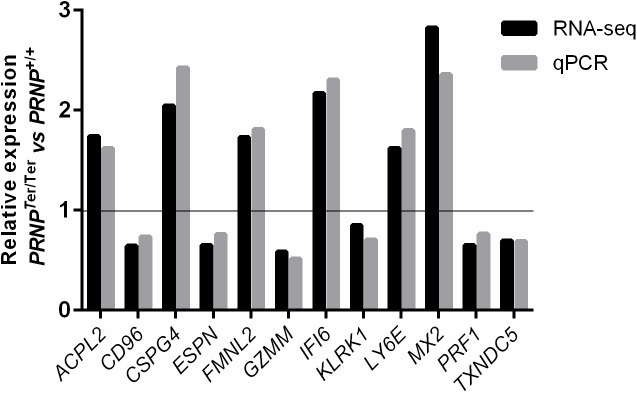

High quality RNA sequencing data (FASTQ) were derived from Beijing Genome Institute (BGI), with an average total reads of 58,806,319 per sample, average total mapped reads of 42,168,758, and average uniquely mapped reads of 38,253,898 per sample (S1 Fig). To validate the sequencing data, primers (S1 Table) were designed for 12 randomly selected differentially expressed genes (DEGs), using reverse transcription (RT) quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) on the original RNA. As shown in Fig 1, qPCR analysis of mRNA levels correlated well with the RNA-seq analysis (r = 0.9616, p < 0.0001, Pearson correlation). Minor discrepancies could be due to sample variations, as RNA from only six goats per group were used for qPCR validation, compared with eight goats per group for RNA-seq analysis.

Fig 1. Validation of RNA sequencing data with quantitative PCR.

Validation of 12 randomly chosen, differentially expressed genes was performed with qPCR using the original RNA. Expression data from the two methods are presented as relative expression between PRNPTer/Ter and PRNP+/+ animals (RNA-seq data n = 8, qPCR n = 6; r = 0.9616, p < 0.0001, Pearson correlation).

Lack of PrPC subtly alters the transcriptome in immune cells

A high correlation was observed between averaged PRNP+/+ and PRNPTer/Ter normalized gene expression data (r = 0.99, Pearson correlation). However, we found that not all PRNP+/+ and PRNPTer/Ter goats could be clearly separated from each other, probably reflecting the phenotypic diversity of the goats (S2 Fig). Despite this, using edgeR [32] and a p-value cut-off < 0.05, 735 genes were differentially expressed between the two genotypes (S1 File). Further filtration of the gene list using cut offs for fold change (log2 FC ± 0.5) and mean number of reads (> 100 reads in one of the groups) generated a high-confidence gene list of 127 DEGs, of which 67 were upregulated and 60 were downregulated in the PRNPTer/Ter genotype (S2 Table). Of note, as we have previously shown that the PBMC cell populations, mainly T cells, B cells and monocytes, are stable between the two genotypes compared in our study [26], the DEGs result from real genotype-associated shifts in gene expression, not shifts in the cell populations. Reassuringly, the PRNP gene was among the DEGs, with very few reads mapping to this locus in the mutant. The chromosomal distribution of the DEGs is found in S3 Fig. The PRNP gene is located on chromosome 13 in goats. Only 1 (SIGLEC1) of the 86 annotated DEGs also maps to chromosome 13. This gene is expressed at a low level and is irrelevant for the findings in our study.

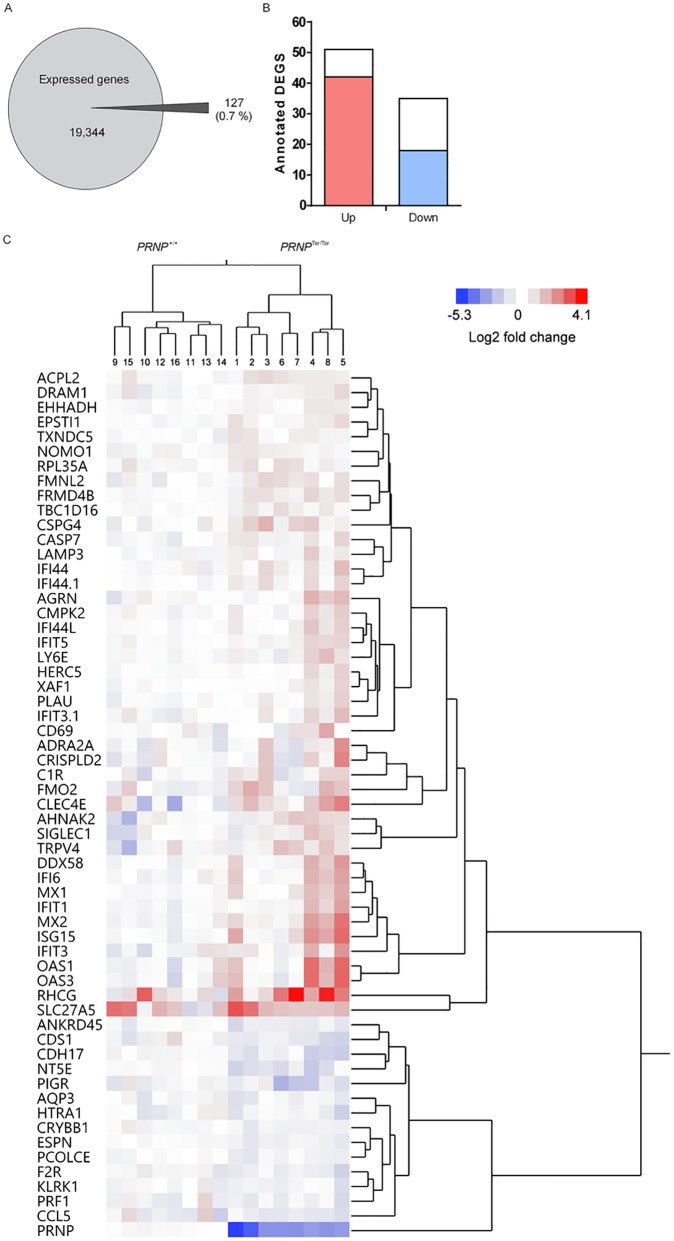

Of the average total number of genes expressed in PBMCs from both genotypes, only 0.7 percent of the genes were altered upon loss of PrPC (Fig 2A). Using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA), of the 127 high-confidence DEGs, 86 genes were functionally annotated. Interestingly, 22 of these genes were categorized as “Viral infection” (p-value = 3.27x10-5), and additional genes were related to other anti-virus-associated terms. The majority of these genes were upregulated in the PRNPTer/Ter genotype compared with the PRNP+/+ genotype. Of the top canonical pathways, “Interferon signaling” was by far the most affected (p-value = 8.92x10-6). Due to these findings, we performed further analyses of the annotated DEGs using the Interferome database [33]. Strikingly, 60 of the 86 annotated DEGs were interferon-responsive genes (Fig 2B). Of these, 42 were upregulated (red bar) and 18 downregulated (blue bar) in the PRNPTer/Ter genotype. Fig 2C shows the inter-individual variation in gene expression of all samples represented in a heatmap, and hierarchical clustering analysis of the 60 interferon-responsive genes revealed a clustering of downregulated and upregulated genes between the PRNP+/+ and PRNPTer/Ter genotypes.

Fig 2. Interferon-responsive genes dominate among the differentially expressed genes in goats lacking PrPC.

Graphical presentation of (A) the total number and percentage of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the two genotypes, compared to the average total number of genes expressed in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from both genotypes, and (B) the total number of upregulated and downregulated annotated DEGs. The fraction of upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) interferon-responsive genes among the DEGs are also shown. (C) Hierarchical clustering of the interferon-responsive genes among the DEGs and expression data from all individual goats of both genotypes. Hierarchical clustering was performed using the ward algorithm on log2-normalized fold changes.

Since the observed data could be due to altered expression levels of interferons or components in type I interferon signaling, we analyzed expression levels of a number of genes that could affect the expression of interferon-responsive genes. However, differences between the genotypes were not detected (Table 1), except for IFNB2-like, which was slightly downregulated in the PRNPTer/Ter genotype (p-value = 0.025).

Table 1. Mean unique reads of genes related to Interferon signaling from PRNP+/+ (n = 8, ± SEM) and PRNPTer/Ter (n = 8, ± SEM) goats.

| Gene symbol | Transcript ID | PRNP+/+ | PRNPTer/Ter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interferons | |||

| IFNA-H-like | XM_005683618.1 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| IFNB2-like | XM_005702021.1 | 63.0 ± 5.3 | 43.4 ± 4.2 * |

| IFNK | XM_005683589.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| IFNO1-like | XM_005683620.1 | 26.5 ± 6.8 | 19.1 ± 4.9 |

| IFNT2A | XM_005683606.1 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.5 |

| IFNG | XM_005680208.1 | 38.4 ± 10.9 | 27.8 ± 4.5 |

| IFNL3 | XM_005692539.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| IFNL4-like | XM_005692540.1 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.2 |

| Interferon receptors | |||

| IFNAR1 | XM_005674742.1 | 11565.5 ± 613.5 | 11818.3 ± 683.0 |

| IFNAR2 | XM_005674684.1 | 3484.1 ± 245.4 | 3664.9 ± 188.7 |

| IFNGR1 | XM_005684807.1 | 3056.4 ± 268.9 | 3772.4 ± 252.6 |

| IFNGR2 | XM_005674741.1 | 7492.8 ± 179.1 | 8209.5 ± 408.9 |

| IFNLR1 | XM_005677011.1 | 95.5 ± 10.8 | 122.4 ± 22.4 |

| Interferon signaling components | |||

| JAK1 | XM_005678310.1 | 31579.9 ± 920.9 | 31909.0 ± 908.7 |

| JAK2 | XM_005683698.1 | 2399.1 ± 109.3 | 2587.5 ± 84.7 |

| JAK3 | XM_005682189.1 | 11636.9 ± 600.5 | 9816.8 ± 603.9 |

| TYK2 | XM_005682457.1 | 4528.3 ± 205.6 | 4775.3 ± 328.4 |

| STAT1 | XM_005676277.1 | 26477.4 ± 2414.9 | 28314.6 ± 1119.4 |

| STAT2 | XM_005680347.1 | 5548.9 ± 332.1 | 6363.6 ± 408.4 |

| STAT3 | XM_005693850.1 | 98.5 ± 10.5 | 92.5 ± 8.2 |

| STAT4 | XM_005676278.1 | 2101.9 ± 158.6 | 1949.5 ± 120.6 |

| STAT5A | XM_005693847.1 | 5250.6 ± 172.7 | 5365.3 ± 194.9 |

| STAT5B | XM_005693846.1 | 4604.1 ± 137.3 | 4511.0 ± 155.2 |

| STAT6 | XM_005680308.1 | 15197.3 ± 704.8 | 15596.6 ± 692.7 |

| IRF1 | XM_005682621.1 | 12308.6 ± 1155.2 | 10936.5 ± 1329.5 |

| IRF2 | XM_005698710.1 | 624.5 ± 26.6 | 663.4 ± 17.1 |

| IRF3 | XM_005692726.1 | 1073.9 ± 74.3 | 1169.1 ± 60.4 |

| IRF4 | XM_005696935.1 | 1482.5 ± 157.3 | 1379.5 ± 140.9 |

| IRF5 | XM_005679456.1 | 764.9 ± 61.4 | 811.8 ± 65.6 |

| IRF6 | XM_005691036.1 | 7.3 ± 2.2 | 5.4 ± 1.9 |

| IRF8 | XM_005691907.1 | 3565.8 ± 219.0 | 3824.8 ± 210.8 |

| IRF9 | XM_005685224.1 | 205.8 ± 16.7 | 234.5 ± 28.2 |

| Inhibitors and enhancers | |||

| IRF2BP-like | XM_005686182.1 | 2686.3 ± 135.5 | 2794.5 ± 123.7 |

| IRF2BP1 | XM_005692789.1 | 1265.3 ± 33.0 | 1232.4 ± 32.3 |

| IRF2BP2 | XM_005699013.1 | 8090.8 ± 600.5 | 8588.9 ± 793.4 |

| PIAS1 | XM_005685148.1 | 1266.8 ± 66.9 | 1320.0 ± 86.4 |

| PIAS2 | XM_005697179.1 | 390.6 ± 16.9 | 405.0 ± 19.2 |

| PIAS3 | XM_005677741.1 | 99.1 ± 7.8 | 99.5 ± 8.1 |

| PIAS4 | XM_005682570.1 | 39.4 ± 2.7 | 40.0 ± 4.8 |

| SOCS2 | XM_005679820.1 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.6 |

| SOCS3 | XM_005694412.1 | 372.0 ± 48.8 | 346.4 ± 47.5 |

| SOCS4 | XM_005685884.1 | 845.4 ± 24.5 | 823.3 ± 28.0 |

| SOCS5 | XM_005686570.1 | 1748.9 ± 82.0 | 1737.6 ± 75.8 |

| SOCS6 | XM_005709580.1 | 137.5 ± 14.4 | 144.6 ± 14.0 |

| SOCS7 | XM_005709575.1 | 2286.3 ± 193.8 | 2144.5 ± 198.7 |

| IL18 | XM_005689450.1 | 21.3 ± 4.5 | 18.9 ± 3.6 |

| PTK2 | XM_005688815.1 | 82.4 ± 11.4 | 92.1 ± 7.4 |

| PTK2B | XM_005684041.1 | 99.3 ± 11.6 | 114.5 ± 17.5 |

*: p = 0.025

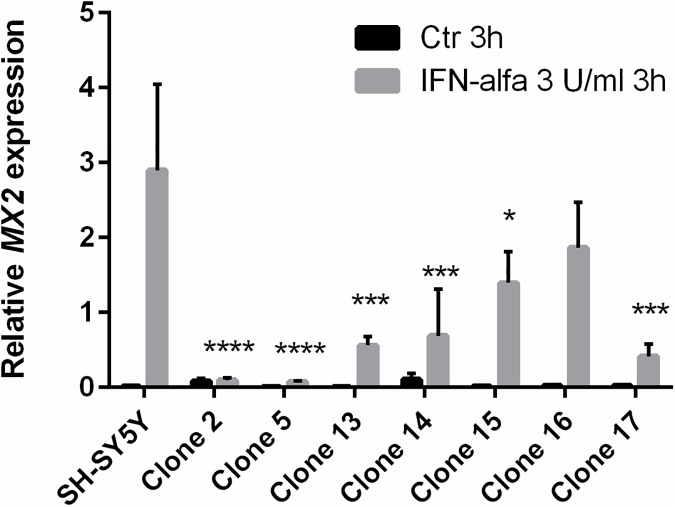

Introduction of PRNP inhibited MX2 gene expression in SH-SY5Y cells

To test whether PrPC could influence IFN-α responsiveness in a cell culture system with a different genetic makeup, we used human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells, which normally express extremely low levels of PrPC. SH-SY5Y clones stably expressing human PrPC were generated (SH-SY5Y PrPhigh) and assessed with regard to glycosylation and proteolytic processing to ensure physiological post-translational modification and trafficking of PrPC (S4 Fig). Eight clones stably expressing PrPC as well as untransfected SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to 3 U/ml IFN-α for 3h. One of the transfected clones showed aberrantly high MX2 gene expression levels and was excluded from the analysis. Of the seven clones included in the experiment, six displayed a significantly reduced response to IFN- α, as assessed by the interferon-responsive gene MX2 expression levels, compared with the untransfected SH-SY5Y cells, using Dunnett’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons (Fig 3) (n = 4, mean ± SEM). The levels of PrPC expression did not directly correlate with the degree of MX2 expression-level inhibition; however, this was not expected due to the complexity of the interferon signaling pathway, and the possible distance between PrPC interference and MX2 gene expression. On average, the clones showed a significantly inhibited response to IFN- α (p-value = 0.0001) compared with the untransfected SH-SY5Y cells, using a two-way ANOVA.

Fig 3. PrPC suppresses upregulation of MX2 gene expression upon INF-α stimulation in SH-SY5Y cells.

Untransfected human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells and seven different clones transfected with a plasmid containing human PRNP to produce SH-SY5Y clones expressing human PrPC, were stimulated for 3h with IFN-α (3 U/ml) (mean ± SEM, n = 4), and MX2 gene expression was assessed. Six out of seven clones displayed a significantly lower response to IFN-α compared with the untransfected SH-SY5Y cells, using Dunnett’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

Increased interferon-responsive gene expression in blood leukocytes devoid of PrPC after LPS challenge

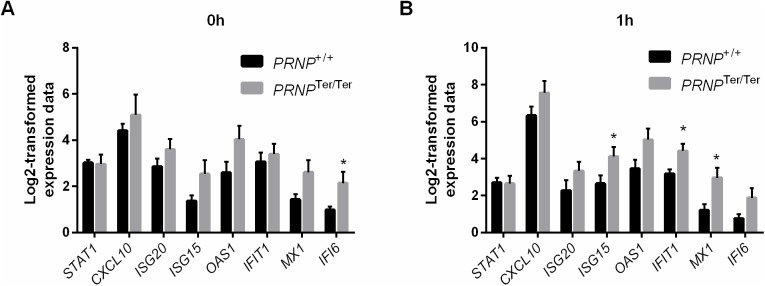

In an independent, parallel study [34, 35], goats were challenged intravenously with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), thereby indirectly stimulating interferon pathways. RNA was extracted from circulating blood leukocytes, and gene expression of interferon-responsive genes was assessed by FLUIDIGM qPCR. As shown in Fig 4A, basal level expression (0h) of several interferon-responsive genes was slightly higher in the PRNPTer/Ter (n = 13) genotype than in the PRNP+/+ (n = 12) genotype, albeit being significantly different for only IFI6 (p-value = 0.037). Moreover, STAT1 mRNA expression levels did not differ between the genotypes. One hour after LPS challenge, the mRNA expression level of interferon-responsive genes increased slightly and the difference between the two genotypes was more pronounced (Fig 4B), with three genes showing a statistically significant difference in expression level (ISG15 (p-value = 0.049), IFIT1 (p-value = 0.02), and MX1 (p-value = 0.019), assessed by multiple t-tests).

Fig 4. Expression of interferon-responsive genes in blood leukocytes after in vivo lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge in goats without PrPC.

RNA was extracted from circulating blood leukocytes from both genotypes, and gene expression was analyzed by FLUIDIGM qPCR. (A) Basal expression level (0 h) of selected interferon-responsive genes and STAT1 in PRNP+/+ (n = 12) and PRNPTer/Ter (n = 13) animals. (B) Gene expression of interferon-responsive genes and STAT1 after in vivo LPS challenge (1 h) from PRNP+/+ (n = 7) and PRNPTer/Ter (n = 8) animals. Values are mean ± SEM. Statistical significance is indicated by *, p-value < 0.05, as assessed by multiple t-tests.

Discussion

Similar to observations in transgenic mice [6], goats [36], and cattle [27] with knockout (KO) of PRNP, the PRNPTer/Ter goats display no obvious loss-of-function phenotype [25, 26]. Consequently, only subtle transcriptomic alterations were expected, corroborating data from KO mouse models [37–41]. Accordingly, this study revealed subtle expression differences affecting less than a percent of the expressed genes. However, analysis of the annotated DEGs using the Interferome database [33], identified a distinct expression profile, with 70 percent of the DEGs being classified as interferon responsive, of which several were among the top upregulated genes. Importantly, animals were age-matched and derived from the same research flock. The health status of this herd is frequently monitored and considered excellent. Prior to sampling, animals were assessed clinically by a veterinarian and found healthy, which was also confirmed by hematological analysis in an accompanying study [26]. Furthermore, we were unable to detect any differences in gene expression levels of neither interferons nor IFN signaling components. A flanking gene problem will also be present in the PRNPTer/Ter goats; however, preliminary data indicate that this is very limited compared to inbred knockout mouse models. In the absence of alternative explanations, we consider the observed gene expression profile to be a true signature of PrPC loss-of-function. It is likely that this profile, which is evident at rest in the outbred and immunocompetent goats, might be even weaker or absent in inbred transgenic mice, housed in pathogen-depleted environments. It is, however, interesting to note that studies of prion disease in mice have revealed a gene expression profile similar to that observed in PrPC-deficient goats. Analysis of transcripts from mouse whole brain throughout the course of experimental CJD revealed an upregulation of several interferon-responsive genes, e.g. OAS, ISG15, and IRF-family members. Importantly, the upregulation of these genes occurred very early in the course of the disease, approximately 50 days before the onset of neuropathological signs and detection of PrPSc [42]. Similar findings were recently reported in another study of prion-infected mice [43]. In a hamster model of scrapie, several interferon-responsive genes, including those encoding OAS and Mx protein, were upregulated during development of scrapie [44]. In addition, three interferon-responsive genes, assessed by qPCR studies, were moderately upregulated in a hamster model and different mouse models inoculated with scrapie strains [45]. Recently, transcriptomic data from cerebellar organotypic cultured slices infected with prions showed that a slight upregulation of several interferon-responsive genes was evident at 38 and 45 days post infection [46]. It is tempting to speculate that some of the observed gene expression alterations at very early stages of prion disease could, at least partly, reflect induced loss-of-PrPC function, and, thus, explain the similarity with the expression profile reported here. Further investigations are clearly needed to test this hypothesis.

Studies of human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells transfected with human PRNP displayed a significantly dampened response (MX2 expression) to a low-level IFN-α stimulation, compared with untransfected cells that are virtually devoid of PrPC. Furthermore, in an independent, parallel study involving older goat kids than those recruited for the RNA seq study, animals were challenged with LPS, which is a potent pro-inflammatory compound. In contrast to mice, which are relatively tolerant towards LPS, goats have a similar sensitivity as humans [34, 35]. In line with data from the present RNA sequencing study, resting state expression levels of interferon-responsive genes in leukocytes were slightly elevated in the PRNPTer/Ter genotype. Interestingly, the expression differences between the genotypes were increased one hour after LPS injection. Apparently, leukocytes without the expression of PrPC upregulated interferon-responsive genes more rapidly than their PrPC-expressing counterparts. The regulation of interferon-responsive genes expression level is multifaceted and tightly controlled at several levels [47, 48], involving receptor downregulation, upregulation of a plethora of inhibitors as well as epigenetic modifications.

Taken together, our data suggest that PrPC contributes to dampening of type I interferon signaling at rest and that loss of PrPC induces a primed state of interferon-responsive genes. Accordingly, direct or indirect stimulation of type I IFN signaling, elicits a somewhat stronger immediate response when PrPC is absent. These data do not conflict with roles acclaimed to the prion protein. Indeed, they might strengthen previous observations and provide mechanistic hints of PrPC physiology.

Material and methods

Animals

The animals (FOTS approval number ID 8058) included in the study were of the Norwegian Dairy Goat Breed obtained from a research herd of approximately 100 winter-fed goats at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences. Based on health surveillance through membership in the Goat health monitoring service and The Norwegian Association of Sheep and Goat Farmers and daily monitoring, the general health status of the herd is considered to be good. The entire flock was previously genotyped [25] concerning PRNP genotypes, and through selective breeding, goat kids with the two genotypes PRNP+/+ (n = 8; 4 female and 4 male) and PRNPTer/Ter (n = 8; 4 female and 4 male) were retrieved. Prior to inclusion in the experiment, all goat kids were examined clinically and found to be healthy.

Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Blood was sampled from the jugular vein into EDTA tubes at 2–3 months of age. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep®, Axis-Shield, Dundee, Scotland) at 1760 x g without brake, and washed with PBS supplemented with EDTA (2 mM). Red blood cells were lysed by brief exposure to sterile water, and washed with PBS supplemented with EDTA (2 mM) prior to counting and trypan blue viability assessment using a Countess® Automated Cell Counter (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Cell culture studies

Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck, Kenilworth, NJ) were cultured in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium and Ham’s F12 (1:1) (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), glutamine and antibiotics (1% streptomycin and penicillin) (all from Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and cultivated in T25 flasks at 37°C with 5% (v/v) CO2 at saturated humidity. SH-SY5Y cells were stably transfected with a plasmid construct, pCI-neo (Promega, Madison, WI) encoding human PRNP, using jetPRIME (Polyplus, Illkirch, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transfected cells were grown under selection pressure of Geneticin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and nine different single clones with variable levels of PrPC (SH-SY5Y PrPhigh) were isolated (S4 Fig). Clone no. 8 showed an abnormal phenotype, and was excluded from the studies.

Western blotting

Untransfected SH-SY5Y cells and transfected SH-SY5Y PrPhigh clones were lysed in homogenizer buffer (Tris HCl 50 uM, NaCl 150 mM, EDTA 1 mM, DOC 0.25%, NP40 1%) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche complete, Roche Holding AG, Basel, Switzerland). Protein concentrations were measured using Protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). To obtain deglycosylated protein, 20 μg of total protein were incubated overnight with PNGase-F (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Fifty μg of protein or the deglycosylated samples were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (12% Criterion™ XT Bis-Tris, Bio-Rad), and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). After incubation with blocking buffer (5% non-fat milk in TBS-Tween) for 90 minutes at room temperature, samples were incubated in 1% non-fat milk in TBS-Tween containing mouse anti-PrPC primary antibody diluted 1:4000 (6H4, Prionics, Thermo Fischer Scientific) over-night at 4°C. Subsequently, the membrane was washed and incubated for 90 minutes in 1% non-fat milk containing Alkaline Phosphatase (AP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG diluted 1:4000 (Novex, Life Technologies, Thermo Fischer Scientific). Membrane was developed using EFC™ substrate (GE Healthcare) and visualized with Typhoon 9200 (Amersham Bioscience, GE Healthcare).

Isolation and sequencing of RNA

Total RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy mini plus kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and purity was analyzed using NanoDrop-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments Inc, Winooski, VT), and quality was assessed before RNA sequencing using RNA Nano Chips on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (both from Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). RNA was stored at -80°C. Individual RNA samples of high quality (RIN ≥ 9.8) were sequenced by mRNA poly-A-tail, paired-end sequencing (Illumina HiSeq 2000) with 91 bp read-lengths (Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI), Hong Kong), retrieving a minimum depth of 5G clean data per sample. In detail, after the total RNA extraction and DNase I treatment, magnetic beads with Oligo (dT) were used to isolate mRNA. Mixed with the fragmentation buffer, the mRNA was fragmented into short fragments, and cDNA was synthesized using the mRNA fragments as templates. Short fragments were purified and resolved with EB buffer for end reparation and single nucleotide A (adenine) addition. The short fragments were connected with adapters. After agarose gel electrophoresis, the suitable fragments were selected for the PCR amplification as templates. During the QC steps, Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System were used in quantification and qualification of the sample library.

For the IFN-studies, RNA quality was assessed by TAE/formamide RNA gel electrophoresis. RNA samples were mixed with formamide (50% v/v, Sigma) and orange loading dye (New England Biolabs), denatured by heating for 5 min at 65°C, put on ice, and loaded on 1% agarose gel containing 1xTAE buffer (0.04 M Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA) and visualized with SYBR™ Safe (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Analysis of RNA sequencing data

Reads were mapped to the goat genome assembly (CHIR_1.0) using SOAP2 [49]. Reads per gene were obtained using SOAP2 and the goat genome annotation (RefSeq, CHIR_1.0). Read counts were normalized to reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) [50]. Testing for differentially expressed genes was performed using the function exactTest in edgeR [32].

Expression analysis by reverse transcription (RT) quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis

cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase, RNase Out, dNTP mix and Random Primers (all from Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at the following conditions: 5 min at 65°C, >1 min on ice, 5 min at 25°C, 1 h at 50°C and 15 min at 70°C.

For the RNA sequencing validation study, qPCR was conducted with LightCycler 480 Sybr Green I Master mix (Roche). cDNA corresponding to 2.5 ng RNA was used per reaction. The samples were run in duplicates in a total volume of 20 μl on a LightCycler 96 System (Roche). Conditions: 5 min at 95°C; 40 cycles of 10 sec at 95°C, 10 sec at 60°C and 10 sec at 72°C; and melting curve with 5 sec at 95°C, 1 min at 65°C and 97°C. Relative expression levels were calculated using a standard curve generated from one randomly selected animal, run in triplicate, with GAPDH as a reference gene, and one randomly selected animal as a positive control. The average of six PRNPTer/Ter animals was divided by the average of six PRNP+/+ animals, and compared relative to RNA sequencing data.

For the interferon-treatment studies using SH-SY5Y cells, qPCR was conducted with LightCycler 480 Sybr Green I Master mix (Roche). cDNA corresponding to 10 ng RNA was used per reaction. The samples were run in triplicate in a total volume of 10 μl on a LightCycler 96 System (Roche). Conditions: 5 min at 95°C; 40 cycles of 10 sec at 95°C, 10 sec at 60°C and 10 sec at 72°C; and melting curve with 5 sec at 95°C, 1 min at 65°C and 97°C. Relative expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCt method. ActB was used as a reference gene. An inter-run calibrator was included on every plate as a positive control. The qPCR-amplified sample was run on a 1% agarose gel, and visualized using SYBR™ Safe (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

LPS challenge and FLUIDIGM qPCR of whole blood leukocyte interferon-responsive genes

An intravenous LPS challenge was performed (0.1 μg/kg, Escherichia coli O26:B6) in 16 Norwegian dairy goats age 6–7 months (8 PRNP+/+ (female) and 8 PRNPTer/Ter (7 female, 1 castrated male)) (FOTS approval number IDs 5827, 6903, and 7881), and 10 controls were included (5 of each genotype). In brief, blood samples were collected in PAX-gene blood RNA tubes before (0 h) and after LPS challenge (1 h). High quality RNA (RIN 9.0 ± 0.34) was extracted using the PAXgene Blood miRNA kit, and cDNA synthesis was performed in two replicates (QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit). The relative expression of ISGs in circulating leukocytes was assessed after qPCR on the Fluidigm Biomark HD platform and data analysis using GenEx5 software (MultiD, Sweden). The full study protocol, method description, and primer sequences can be found in [34, 35].

Statistical analysis

Multiple t-tests or two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons were used for statistical analysis of the data using Graph Pad Prism v. 6.07 (Graphpad, La Jolla, CA). For correlation analysis, the Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated. Mean values are presented ± SEM.

Ethics statement

The animal experiments were performed in compliance with ethical guidelines, and approved by the Norwegian Animal Research Authority (FOTS approval number IDs 8058, 5827, 6903, and 7881) with reference to the Norwegian regulation on animal experimentation (FOR-2015-06-18-761).

Supporting information

Total reads, total mapped reads and uniquely mapped reads across all samples, n = 16, 8 of each genotype.

(TIF)

Hierarchical clustering dendrogram of all genes after normalization of expression data (RPKM) using Euclidean distance and complete linkage.

(TIF)

(A) Frequency of differentially expressed genes (735 genes) per chromosome. Total number of genes per chromosome were obtained from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), based on the Capra hircus CHIR_1.0-Primary Assembly. (B) Chromosomal distribution of annotated differentially expressed genes (86 genes).

(TIF)

Protein expression of PrPC for untreated and PNGase-F-treated untransfected human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells and SH-SY5Y clones transfected with human PRNP (n = 8), determined by Western Blot analysis using 6H4 mouse anti-PrPC as the primary antibody. Protein bands correspond to glycosylated PrPC, deglycosylated PrPC and PrPC C1 fragment as indicated.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Skogtvedt Røed and Berit Christophersen for skillful laboratory work, Agnes Klouman and the staff at the Animal Production Experimental Centre, and Dag Inge Våge and Torfinn Nome for technical help with the sequencing data. The authors acknowledge Lucy Robertson for proofreading the manuscript, and Ingrid Olsaker for use of the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software.

Data Availability

All FASTQ files are available from the SRA database (SRA study accession number SRP102642).

Funding Statement

MAT received funding from the Norwegian Research Council, Grant number 227386/E40 (http://www.forskningsradet.no/no/Forsiden/1173185591033). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Prusiner SB. Prions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1998;95(23):13363–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linden R, Martins VR, Prado MAM, Cammarota M, Izquierdo I, Brentani RR. Physiology of the prion protein. Physiological Reviews. 2008;88(2):673–728. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wopfner F, Weidenhöfer G, Schneider R, von Brunn A, Gilch S, Schwarz TF, et al. Analysis of 27 mammalian and 9 avian PrPs reveals high conservation of flexible regions of the prion protein. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1999;289(5):1163–78. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.1999.2831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rongyan Z, Xianglong L, Lanhui L, Xiangyun L, Fujun F. Evolution and differentiation of the prion protein gene (PRNP) among species. Journal of Heredity. 2008;99(6):647–52. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esn073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peralta OA, Huckle WR, Eyestone WH. Developmental expression of the cellular prion protein (PrPC) in bovine embryos. Molecular Reproduction and Development. 2012;79(7):488–98. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bueler H, Fischer M, Lang Y, Bluethmann H, Lipp H-P, DeArmond SJ, et al. Normal development and behaviour of mice lacking the neuronal cell-surface PrP protein. Nature. 1992;356(6370):577–82. doi: 10.1038/356577a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manson JC, Clarke AR, Hooper ML, Aitchison L, McConnell I, Hope J. 129/Ola mice carrying a null mutation in PrP that abolishes mRNA production are developmentally normal. Mol Neurobiol. 1994;8(2–3):121–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02780662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Büeler H, Aguzzi A, Sailer A, Greiner RA, Autenried P, Aguet M, et al. Mice devoid of PrP are resistant to scrapie. Cell. 1993;73(7):1339–47. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(93)90360-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakaguchi S, Katamine S, Nishida N, Moriuchi R, Shigematsu K, Sugimoto T, et al. Loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells in aged mice homozygous for a disrupted PrP gene. Nature. 1996;380(6574):528–31. doi: 10.1038/380528a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore RC, Mastrangelo P, Bouzamondo E, Heinrich C, Legname G, Prusiner SB, et al. Doppel-induced cerebellar degeneration in transgenic mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(26):15288–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251550798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossi D, Cozzio A, Flechsig E, Klein MA, Rülicke T, Aguzzi A, et al. Onset of ataxia and Purkinje cell loss in PrP null mice inversely correlated with Dpl level in brain. Journal Article. 2001;20(4):694–702. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yokoyama T, Kimura KM, Ushiki Y, Yamada S, Morooka A, Nakashiba T, et al. In vivo conversion of cellular prion protein to pathogenic isoforms, as monitored by conformation-specific antibodies. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(14):11265–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008734200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nuvolone M, Kana V, Hutter G, Sakata D, Mortin-Toth SM, Russo G, et al. SIRPα polymorphisms, but not the prion protein, control phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2013;210(12):2539–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steele AD, Lindquist S, Aguzzi A. The prion protein knockout mouse: A phenotype under challenge. Prion. 2007;1(2):83–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baumann F, Tolnay M, Brabeck C, Pahnke J, Kloz U, Niemann HH, et al. Lethal recessive myelin toxicity of prion protein lacking its central domain. Journal Article. 2007;26(2):538–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bremer J, Baumann F, Tiberi C, Wessig C, Fischer H, Schwarz P, et al. Axonal prion protein is required for peripheral myelin maintenance. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(3):310–8. http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/v13/n3/suppinfo/nn.2483_S1.html. doi: 10.1038/nn.2483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nuvolone M, Hermann M, Sorce S, Russo G, Tiberi C, Schwarz P, et al. Strictly co-isogenic C57BL/6J-Prnp−/− mice: A rigorous resource for prion science. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2016;213(3):313–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tobler I, Gaus SE, Deboer T, Achermann P, Fischer M, Rulicke T, et al. Altered circadian activity rhythms and sleep in mice devoid of prion protein. Nature. 1996;380(6575):639–42. doi: 10.1038/380639a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walz R, Amaral OB, Rockenbach IC, Roesler R, Izquierdo I, Cavalheiro EA, et al. Increased sensitivity to seizures in mice lacking cellular prion protein. Epilepsia. 1999;40(12):1679–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb01583.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spudich A, Frigg R, Kilic E, Kilic Ü, Oesch B, Raeber A, et al. Aggravation of ischemic brain injury by prion protein deficiency: Role of ERK-1/-2 and STAT-1. Neurobiology of Disease. 2005;20(2):442–9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2005.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLennan NF, Brennan PM, McNeill A, Davies I, Fotheringham A, Rennison KA, et al. Prion protein accumulation and neuroprotection in hypoxic brain damage. The American Journal of Pathology. 2004;165(1):227–35. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63291-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mestas J, Hughes CCW. Of mice and not men: Differences between mouse and human immunology. The Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(5):2731–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis MM. A prescription for human immunology. Immunity. 2008;29(6):835–8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolker J. Model organisms: There's more to life than rats and flies. Nature. 2012;491(7422):31–3. doi: 10.1038/491031a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benestad S, Austbo L, Tranulis M, Espenes A, Olsaker I. Healthy goats naturally devoid of prion protein. Veterinary Research. 2012;43(1):87 doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-43-87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reiten MR, Bakkebø MK, Brun-Hansen H, Lewandowska-Sabat AM, Olsaker I, Tranulis MA, et al. Hematological shift in goat kids naturally devoid of prion protein. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2015;3:44 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2015.00044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richt JA, Kasinathan P, Hamir AN, Castilla J, Sathiyaseelan T, Vargas F, et al. Production of cattle lacking prion protein. Nature biotechnology. 2007;25(1):132 doi: 10.1038/nbt1271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dürig J, Giese A, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Rosenthal C, Schmücker U, Bieschke J, et al. Differential constitutive and activation-dependent expression of prion protein in human peripheral blood leucocytes. British Journal of Haematology. 2000;108(3):488–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01881.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isaacs JD, Jackson GS, Altmann DM. The role of the cellular prion protein in the immune system. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2006;146(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03194.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isaacs JD, Garden OA, Kaur G, Collinge J, Jackson GS, Altmann DM. The cellular prion protein is preferentially expressed by CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Immunology. 2008;125(3):313–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02853.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mariante RM, Nóbrega A, Martins RAP, Areal RB, Bellio M, Linden R. Neuroimmunoendocrine regulation of the prion protein in neutrophils. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287(42):35506–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.394924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rusinova I, Forster S, Yu S, Kannan A, Masse M, Cumming H, et al. INTERFEROME v2.0: an updated database of annotated interferon-regulated genes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;41(Database issue):D1040–D6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salvesen Ø, Reiten MR, Heegaard PMH, Tranulis MA, Espenes A, Skovgaard K, et al. Activation of innate immune genes in caprine blood leukocytes after systemic endotoxin challenge. BMC Veterinary Research. 2016;12:241 doi: 10.1186/s12917-016-0870-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salvesen Ø, Reiten MR, Espenes A, Bakkebø MK, Tranulis MA, Ersdal C. LPS-induced systemic inflammation reveals an immunomodulatory role for the prion protein at the blood-brain interface. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:106 doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0879-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu G, Chen J, Xu Y, Zhu C, Yu H, Liu S, et al. Generation of goats lacking prion protein. Molecular Reproduction and Development. 2009;76(1):3–. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benvegnù S, Roncaglia P, Agostini F, Casalone C, Corona C, Gustincich S, et al. Developmental influence of the cellular prion protein on the gene expression profile in mouse hippocampus. Physiol Genomics. 2011;43(12):711–25. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00205.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Satoh J-i, Kuroda Y, Katamine S. Gene expression profile in prion protein-deficient fibroblasts in culture. The American Journal of Pathology. 2000;157(1):59–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramljak S, Asif AR, Armstrong VW, Wrede A, Groschup MH, Buschmann A, et al. Physiological role of the cellular prion protein (PrPc): Protein profiling study in two cell culture systems. Journal of Proteome Research. 2008;7(7):2681–95. doi: 10.1021/pr7007187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chadi S, Young R, Le Guillou S, Tilly G, Bitton F, Martin-Magniette M-L, et al. Brain transcriptional stability upon prion protein-encoding gene invalidation in zygotic or adult mouse. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:448–. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crecelius AC, Helmstetter D, Strangmann J, Mitteregger G, Fröhlich T, Arnold GJ, et al. The brain proteome profile is highly conserved between Prnp−/− and Prnp+/+ mice. NeuroReport. 2008;19(10):1027–31. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283046157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baker CA, Lu ZY, Manuelidis L. Early induction of interferon-responsive mRNAs in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Journal of NeuroVirology. 2004;10:29–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carroll JA, Striebel JF, Race B, Phillips K, Chesebro B. Prion infection of mouse brain reveals multiple new upregulated genes involved in neuroinflammation or signal transduction. Journal of Virology. 2015;89(4):2388–404. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02952-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riemer C, Queck I, Simon D, Kurth R, Baier M. Identification of upregulated genes in scrapie-infected brain tissue. Journal of Virology. 2000;74(21):10245–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stobart MJ, Parchaliuk D, Simon SLR, LeMaistre J, Lazar J, Rubenstein R, et al. Differential expression of interferon responsive genes in rodent models of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy disease. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2007;2:5–. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-2-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herrmann US, Sonati T, Falsig J, Reimann RR, Dametto P, O’Connor T, et al. Prion infections and anti-PrP antibodies trigger converging neurotoxic pathways. PLoS Pathogens. 2015;11(2):e1004662 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ivashkiv LB, Donlin LT. Regulation of type I interferon responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(1):36–49. doi: 10.1038/nri3581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Porritt RA, Hertzog PJ. Dynamic control of type I IFN signalling by an integrated network of negative regulators. Trends in Immunology. 2015;36(3):150–60. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li R, Yu C, Li Y, Lam T-W, Yiu S-M, Kristiansen K, et al. SOAP2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(15):1966–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Meth. 2008;5(7):621–8. http://www.nature.com/nmeth/journal/v5/n7/suppinfo/nmeth.1226_S1.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Total reads, total mapped reads and uniquely mapped reads across all samples, n = 16, 8 of each genotype.

(TIF)

Hierarchical clustering dendrogram of all genes after normalization of expression data (RPKM) using Euclidean distance and complete linkage.

(TIF)

(A) Frequency of differentially expressed genes (735 genes) per chromosome. Total number of genes per chromosome were obtained from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), based on the Capra hircus CHIR_1.0-Primary Assembly. (B) Chromosomal distribution of annotated differentially expressed genes (86 genes).

(TIF)

Protein expression of PrPC for untreated and PNGase-F-treated untransfected human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells and SH-SY5Y clones transfected with human PRNP (n = 8), determined by Western Blot analysis using 6H4 mouse anti-PrPC as the primary antibody. Protein bands correspond to glycosylated PrPC, deglycosylated PrPC and PrPC C1 fragment as indicated.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All FASTQ files are available from the SRA database (SRA study accession number SRP102642).