Abstract

Background

Major concerns about the safety of pretransplant amiodarone use have been raised. As a result of its long half-life, the cardiac allograft is exposed to amiodarone posing potential risks such as bradycardia, requirement for pacemaker implantation, or increased mortality after heart transplantation (HTX).

Objective

The aim of this study is to investigate the posttransplant outcomes of patients with no, acute, or chronic amiodarone use before HTX.

Methods

This retrospective single-center study included 530 adult patients who received HTX between 06/1989 and 12/2012. Patients were stratified by their amiodarone therapy before HTX: no continuous amiodarone use (≤90 days before HTX), acute amiodarone use (≤90 days before HTX), and chronic amiodarone use (>90 days before HTX). Differences between the 3 groups in demographics, posttransplant medication, echocardiographic features, heart rates including occurrences of bradycardia, permanent pacemaker implantation, atrial fibrillation (AF), and survival were analyzed.

Results

A total of 412 patients (77.7%) were in the “no amiodarone” group, 23 patients (4.4%) in the “acute amiodarone” group, and 95 patients (17.9%) in the “chronic amiodarone” group. Left ventricular ejection fraction (P=0.5819), heart rates including occurrence of bradycardia during posttransplant week 1 (P=0.0979 and P=0.2695), week 2 (P=0.1214 and P=0.8644), week 3 (P=0.1033 and P=0.8894), and week 4 (P=0.2892 and P=0.8644), permanent pacemaker implantation within 30-day (P=0.8644), or overall follow-up after HTX (P=0.8664) were not significant between groups. Patients with chronic pretransplant amiodarone therapy had the lowest rate of early posttransplant AF (P=0.0065). There was no statistically significant difference between groups in 30-day (P=0.8656), 1-year (P=1.0000), 2-year (P=0.8763), 5-year (P=0.5174), or overall posttransplant follow-up mortality (P=0.1936).

Conclusion

Administration of acute or chronic pretransplant amiodarone was not related to an increased occurrence of bradycardia, requirement for permanent pacemaker implantation, or mortality after HTX. Importantly, chronic amiodarone use effectively reduced early AF after HTX, whereas acute amiodarone use showed no such effect.

Keywords: amiodarone, atrial fibrillation, bradycardia, heart transplantation, pacemaker, survival

Introduction

Major concerns about the safety of pretransplant amiodarone use in patients with congestive heart failure have been raised.1 As a result of its long half-life, the cardiac allograft is exposed to amiodarone posing potential risks.2 Several studies reported an increased posttransplant mortality in patients with amiodarone therapy before heart transplantation (HTX),3–5 whereas others found no difference.6–9

Moreover, amiodarone use before HTX has been linked to bradycardia and conduction disturbances along with an increased requirement for permanent pacemaker implantation after HTX.10,11

Due to its slow distribution to tissue, amiodarone may take several weeks to months to reach steady-state tissue concentrations and exert optimal antiarrhythmic effects.12,13 Additionally, the reported half-life of amiodarone varies extremely, starting with a half-life of only a few hours in patients with a single dose, going up to a half-life of ~2 months in patients with short-term amiodarone use, and having the longest half-life of ~4 months in patients with long-term use of amiodarone.13–15 Therefore, meticulous differentiation between acute and chronic amiodarone use seems essential.

In a recent study, our group showed that long-term amiodarone therapy before HTX (≥12 months) was not related to an increased posttransplant mortality and significantly reduced early atrial fibrillation (AF) after HTX.9 However, the question whether short-term amiodarone therapy before HTX might be as safe and protective against AF after HTX as long-term amiodarone use before HTX remains unanswered as available data are inconclusive.1,16 Besides, there is insufficient information about the effects of acute and chronic amiodarone use before HTX on heart rates including occurrences of bradycardia and requirement for permanent pacemaker implantation after HTX.1,16

Hence, this study was designed to compare outcomes after HTX between patients with no, acute, or chronic pre-transplant amiodarone use with a focus on posttransplant medication, echocardiographic features, heart rates including bradycardia (heart rate <60 beats per minute [bpm]), requirement for permanent pacemaker implantation, early AF, and survival.

Materials and methods

Patients

This study was approved by the institutional review board (Ethikkommission der Medizinischen Fakultät Heidelberg). It was based upon the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). All adult patients at the Heidelberg University Hospital receiving HTX between 06/1989 and 12/2012 were included except for patients with repeated HTX. Data were taken from the clinical routine and analyzed in pseudonymized form. As only clinical routine data were used for this study, no additional written informed consent was required from the patients.9,17,18

Patients were stratified by their amiodarone therapy before HTX: subjects without continuous amiodarone use within 90 days before HTX were summarized in the “no amiodarone” (NA) group, those with continuous amiodarone use within 90 days before HTX were summarized in the “acute amiodarone” (AA) group, and patients with continuous amiodarone use for >90 days before HTX were summarized in the “chronic amiodarone” (CA) group. Patients with prior (terminated >90 days before HTX) or intermittent amiodarone use were added to the NA group.

Indications for pretransplant amiodarone use included the following 4 categories: ventricular fibrillation (VF), ventricular tachycardia (VT), Wolff–Parkinson–White (WPW) syndrome, and AF. Furthermore, daily dose (in mg) and duration (in days) of amiodarone therapy before HTX were assessed.

Patient characteristics covered recipient data, comorbidities, and principal diagnoses for HTX. Furthermore, donor data, transplant sex mismatch, and perioperative data were analyzed. Analysis of posttransplant outcomes included echocardiographic features, heart rates including occurrences of bradycardia, permanent pacemaker implantation, AF, and survival.

Follow-up

Posttransplant follow-up was performed according to the center standard. Early posttransplant heart rhythm assessment was based upon all available records (≤30 days after HTX). Continuous heart rhythm telemetry monitoring was applied during the initial hospital stay. We performed 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG) regularly and in case of any suspected arrhythmic disorder. Before discharge, 24-hour-holter-recording was performed.9,17,18

After discharge, patients were routinely followed up monthly within the first 6 months, thereafter bimonthly until 12 months after HTX, and then thrice annually. Follow-up appointments included taking of medical history, physical examination, ECG, and laboratory analysis including monitoring of immunosuppressive drug level. Moreover, endomyocardial biopsy and echocardiography were routinely done.9,17–20

Medication after HTX

According to the center standard, posttransplant medication including immunosuppressive regimen was administered. Laboratory analysis was used to routinely monitor immuno-suppressive drug target levels. The immunosuppressive drug regimen consisting of azathioprine (AZA) and cyclosporine A (CsA) was consecutively substituted by mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and CsA from 2001 onwards, and by MMF and tacrolimus (TAC) from 2006 onwards. Concurrently, steroids (prednisolone) were given in the initial posttrans-plant period.9,17,18

Statistical analysis

SAS (Version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. Data were displayed as absolute number (n) with percentage (%) or as mean ± standard deviation. Continuous variables were analyzed with Student’s t-test or analysis of variance, whereas categorical variables were analyzed with chi-squared test. Log-rank tests (Kaplan–Meier estimator) were applied for analyzing survival after HTX. Statistical significance was defined as a P-value of <0.0500.9,17,18

Results

Indications for acute and chronic amiodarone use

Acute amiodarone use indications prior to HTX were AF in 1 patient (4.3%), VF in 2 patients (8.7%), and VT in 20 patients (87.0%). Indications for chronic amiodarone use before HTX covered WPW syndrome in 1 patient (1.1%), VF in 8 patients (8.4%), AF in 13 patients (13.7%), and VT in 73 patients (76.8%).

Daily dose and duration of amiodarone

Patients with acute amiodarone use before HTX had a mean intake duration of 34.7±23.1 days, ranging from 3 to 77 days. Mean daily dose was 282.6±225.8 mg, spanning from 200.0 to 1,000.0 mg daily. Mean duration of chronic amiodarone use prior to HTX was 798.2±774.1 days, ranging from 101 to 5,124 days. Mean daily dose was 225.3±78.1 mg, ranging from 100.0 to 600.0 mg per day.

Patients requiring amiodarone therapy initially received a loading dose of ~1,000.0 mg daily until a total amount of 10.0 g was achieved. Due to the differences in intake duration in patients with acute amiodarone use before HTX, not all patients received full loading dose.

Demographics

This study included 530 patients receiving HTX. A total of 412 patients were in the NA group, 23 patients were in the AA group, and 95 patients were in the CA group. Patients in the NA group had a mean age of 51.6±10.8 years at HTX, a mean body mass index (BMI) of 24.7±3.9 kg/m2, and 317 of 412 (76.9%) were male. The mean posttransplant follow-up time in the NA group was 6.8±6.1 years. In the AA group, mean recipient age was 51.5±9.2 years, mean BMI was 24.4±3.5 kg/m2, and 19 of 23 (82.6%) were male. The mean posttransplant follow-up time covered 6.2±5.7 years. The CA group had a mean age of 52.6±9.0 years at HTX, a mean BMI of 25.3±3.6 kg/m2, and 76 of 95 (80.0%) were male. The mean posttransplant follow-up time was 7.3±6.6 years.

Regarding recipient comorbidities, there were no statistically significant differences between the 3 groups in terms of coronary artery disease (P=0.6071), arterial hypertension (P=0.4473), dyslipidemia (P=0.2305), diabetes mellitus (P=0.9445), and renal insufficiency (P=0.3118). Donor data including age (P=0.6796), percentage of male sex (P=0.7114), and BMI (P=0.4124) indicated no statistically significant differences.

Concerning the principal diagnosis for HTX, significantly fewer patients with valvular heart disease (NA group: 6.8%, AA group: 4.4%, and CA group: 0.0%, P=0.0309) and cardiac amyloidosis (NA group: 8.2%, AA group: 4.4%, and CA group: 1.1%, P=0.0379) were found in the CA group.

There was no statistically significant difference in nonischemic cardiomyopathy (CMP; P=0.1650) or ischemic CMP (P=0.8233) as principal diagnosis for HTX. Additionally, we could not detect relevant differences in terms of biatrial HTX (P=0.3605), bicaval HTX (P=0.2434), total orthotopic HTX (P=0.0613), transplant sex mismatch (P=0.6602), ischemic time (P=0.7482), prolonged ischemic time ≥240 min (P=0.8160), or length of initial hospital stay (P=0.1475). Demographics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Parameter | No use of amiodarone before HTX (n=412) | Acute use of amiodarone before HTX (n=23) | Chronic use of amiodarone before HTX (n=95) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient data | ||||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 51.6±10.8 | 51.5±9.2 | 52.6±9.0 | 0.7037 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 317 (76.9%) | 19 (82.6%) | 76 (80.0%) | 0.6883 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 24.7±3.9 | 24.4±3.5 | 25.3±3.6 | 0.3807 |

| CAD, n (%) | 168 (40.8%) | 10 (43.5%) | 44 (46.3%) | 0.6071 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 218 (52.9%) | 13 (56.5%) | 57 (60.0%) | 0.4473 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 257 (62.4%) | 14 (60.9%) | 68 (71.6%) | 0.2305 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 140 (34.0%) | 8 (34.7%) | 34 (35.8%) | 0.9445 |

| Renal insufficiency,^ n (%) | 230 (55.8%) | 14 (60.9%) | 61 (64.2%) | 0.3118 |

| Principal diagnosis for HTX | ||||

| Nonischemic CMP, n (%) | 212 (51.5%) | 13 (56.5%) | 59 (62.1%) | 0.1650 |

| Ischemic CMP, n (%) | 138 (33.5%) | 8 (34.7%) | 35 (36.8%) | 0.8233 |

| Valvular heart disease, n (%) | 28 (6.8%) | 1 (4.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0309* |

| Cardiac amyloidosis, n (%) | 34 (8.2%) | 1 (4.4%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0.0379* |

| Donor data | ||||

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 39.5±13.4 | 42.0±12.1 | 39.6±12.8 | 0.6796 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 187 (45.4%) | 11 (47.8%) | 39 (41.1%) | 0.7114 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 24.5±4.0 | 24.0±1.8 | 25.0±4.2 | 0.4124 |

| Transplant sex mismatch | ||||

| Mismatch, n (%) | 174 (42.2%) | 10 (43.5%) | 45 (47.4%) | 0.6602 |

| Donor (m) to recipient (f), n (%) | 22 (5.3%) | 1 (4.4%) | 4 (4.2%) | 0.8908 |

| Donor (f) to recipient (m), n (%) | 152 (36.9%) | 9 (39.1%) | 41 (43.2%) | 0.5233 |

| Perioperative data | ||||

| Biatrial HTX, n (%) | 129 (31.3%) | 4 (17.4%) | 28 (29.5%) | 0.3605 |

| Bicaval HTX, n (%) | 96 (23.3%) | 4 (17.4%) | 15 (15.8%) | 0.2434 |

| Total orthotopic HTX, n (%) | 187 (45.4%) | 15 (65.2%) | 52 (54.7%) | 0.0613 |

| Ischemic time, (min), mean ± SD | 212.2±64.8 | 215.9±66.8 | 207.1±66.6 | 0.7482 |

| Ischemic time ≥240 min, n (%) | 135 (32.8%) | 9 (39.1%) | 31 (32.6%) | 0.8160 |

| LOS (days), mean ± SD | 42.0±21.4 | 47.7±27.0 | 46.3±26.0 | 0.1475 |

Notes:

Glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Statistically significant (P<0.05).

Abbreviations: HTX, heart transplantation; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CMP, cardiomyopathy; m, male; f, female; LOS, length of initial hospital stay; SD, standard deviation.

Initial medication after HTX

The administration of CsA (P=0.0630) or TAC (P=0.0630) did not differ significantly. Furthermore, we could not find a statistically significant difference in the initial immunosuppressive drug therapy between the 3 groups considering AZA (P=0.2598) or MMF (P=0.2598).

Comparison of the initial posttransplant medication revealed no differences in terms of acetylsalicylic acid (P=0.6711), beta blocker (P=0.2560), ivabradine (P=0.8067), calcium channel blocker (P=0.7071), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/sartan (P=0.2964), or statin (P=0.6976). The initial medication after HTX is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Initial medication after HTX

| Parameter | No use of amiodarone before HTX (n=412) | Acute use of amiodarone before HTX (n=23) | Chronic use of amiodarone before HTX (n=95) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclosporine A, n (%) | 275 (66.7%) | 12 (52.2%) | 53 (55.8%) | 0.0630 |

| Tacrolimus, n (%) | 137 (33.3%) | 11 (47.8%) | 42 (44.2%) | 0.0630 |

| Azathioprine, n (%) | 215 (52.2%) | 9 (39.1%) | 43 (45.3%) | 0.2598 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil, n (%) | 197 (47.8%) | 14 (60.9%) | 52 (54.7%) | 0.2598 |

| Steroids, n (%) | 412 (100.0%) | 23 (100.0%) | 95 (100.0%) | NA |

| Acetylsalicylic acid, n (%) | 31 (7.5%) | 1 (4.3%) | 9 (9.5%) | 0.6711 |

| Beta blocker, n (%) | 66 (16.0%) | 4 (17.4%) | 9 (9.5%) | 0.2560 |

| Ivabradine, n (%) | 23 (5.6%) | 2 (8.7%) | 5 (5.3%) | 0.8067 |

| Calcium channel blocker, n (%) | 103 (25.0%) | 6 (26.1%) | 20 (21.1%) | 0.7071 |

| Dihydropyridine, n (%) | 43 (10.4%) | 2 (8.7%) | 6 (6.3%) | 0.4650 |

| Non-dihydropyridine, n (%) | 60 (14.6%) | 4 (17.4%) | 14 (14.8%) | 0.9329 |

| ACE inhibitor/sartan, n (%) | 194 (47.1%) | 9 (39.1%) | 37 (38.9%) | 0.2964 |

| Diuretic, n (%) | 412 (100.0%) | 23 (100.0%) | 95 (100.0%) | NA |

| Statin, n (%) | 146 (35.4%) | 7 (30.4%) | 37 (38.9%) | 0.6976 |

| Gastric protection (PPI/H2 blocker), n (%) | 412 (100.0%) | 23 (100.0%) | 95 (100.0%) | NA |

Abbreviations: HTX, heart transplantation; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; H2, histamine receptor; NA, not applicable.

Early posttransplant echocardiographic features

Echocardiographic features within 30 days after HTX showed no statistically significant differences between the 3 groups, such as diastolic diameter in the right atrium (P=0.8042), the left atrium (P=0.4523), the right ventricle (P=0.2782), or the left ventricle (P=0.4604). Furthermore, there were no statistically significant differences in terms of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF; P=0.5819), mitral regurgitation (P=0.9560), or tricuspid regurgitation (P=0.6044). Echocardiographic features within 30 days after HTX are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Echocardiographic features within 30 days after HTX

| Parameter | No use of amiodarone before HTX (n=412) | Acute use of amiodarone before HTX (n=23) | Chronic use of amiodarone before HTX (n=95) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| End-diastolic diameter | ||||

| Normal RA (<35 mm), n (%) | 222 (53.9%) | 14 (60.9%) | 52 (54.7%) | 0.8042 |

| Normal LA (<40 mm), n (%) | 191 (46.4%) | 13 (56.5%) | 49 (51.6%) | 0.4523 |

| Normal RV (<30 mm), n (%) | 345 (83.7%) | 17 (73.9%) | 83 (87.4%) | 0.2782 |

| Normal LV (<55 mm), n (%) | 380 (92.2%) | 21 (91.3%) | 91 (95.8%) | 0.4604 |

| LVEF | ||||

| ≥55%, n (%) | 372 (90.3%) | 21 (91.3%) | 89 (93.7%) | 0.5819 |

| <55%, n (%) | 40 (9.7%) | 2 (8.7%) | 6 (6.3%) | |

| 45%–54%, n (%) | 10 (2.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.1%) | |

| 30%–44%, n (%) | 7 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| <30%, n (%) | 23 (5.6%) | 2 (8.7%) | 4 (4.2%) | |

| Mitral regurgitation | ||||

| No, n (%) | 315 (76.5%) | 17 (73.9%) | 72 (75.8%) | 0.9560 |

| Yes, n (%) | 97 (23.5%) | 6 (26.1%) | 23 (24.2%) | |

| Mild, n (%) | 95 (23.0%) | 5 (21.7%) | 23 (24.2%) | |

| Moderate, n (%) | 2 (0.5%) | 1 (4.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Severe, n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | ||||

| No, n (%) | 259 (62.9%) | 16 (69.6%) | 64 (67.4%) | 0.6044 |

| Yes, n (%) | 153 (37.1%) | 7 (30.4%) | 31 (32.6%) | |

| Mild, n (%) | 89 (21.6%) | 1 (4.3%) | 22 (23.1%) | |

| Moderate, n (%) | 41 (9.9%) | 4 (17.4%) | 7 (7.4%) | |

| Severe, n (%) | 23 (5.6%) | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (2.1%) |

Abbreviations: HTX, heart transplantation; RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

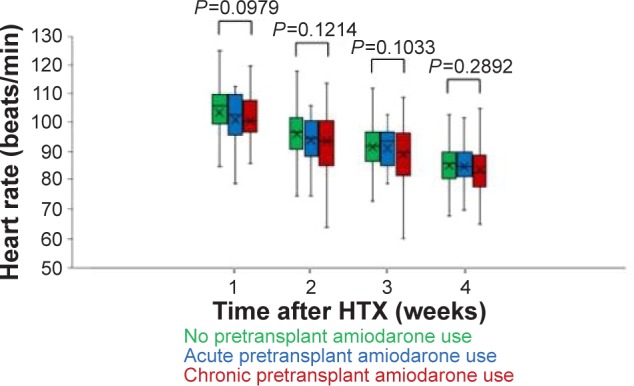

Early posttransplant heart rates

Comparison of heart rates after HTX showed no statistically significant differences between groups during post-transplant week 1 (NA group: 103.8±13.0 bpm, AA group: 101.3±9.9 bpm, and CA group: 100.9±10.2 bpm, P=0.0979), week 2 (NA group: 96.3±10.3 bpm, AA group: 94.1±8.2 bpm, and CA group: 94.0±11.1 bpm, P=0.1214), week 3 (NA group: 91.7±9.3 bpm, AA group: 91.3±6.7 bpm, and CA group: 89.4±9.5 bpm, P=0.1033), or week 4 (NA group: 85.6±8.6 bpm, AA group: 85.2±6.9 bpm, and CA group: 84.0±8.0 bpm, P=0.2892). Heart rates during weeks 1–4 after HTX are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Heart rates during weeks 1–4 after HTX.

Note: Comparison of posttransplant mean weekly heart rate between patients without amiodarone therapy before HTX, with acute amiodarone therapy before HTX, and with chronic amiodarone therapy before HTX.

Abbreviation: HTX, heart transplantation.

Bradycardia and permanent pacemaker implantation after HTX

There were no statistically significant differences between groups regarding bradycardia (heart rate <60 bpm) during posttransplant week 1 (P=0.2695), week 2 (P=0.8644), week 3 (P=0.8894), or week 4 (P=0.8644). A total of 22 patients (4.2%) required a permanent pacemaker implantation during overall follow-up (excluding patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator or cardiac resynchronization therapy devices).

Groups did not differ significantly in terms of permanent pacemaker implantation within 30-day (NA group: 3 of 412 [0.7%], AA group: 0 of 23 [0.0%], and CA group: 1 of 95 [1.1%], P=0.8644), 1-year (NA group: 5 of 405 [1.2%], AA group: 0 of 23 [0.0%], and CA group: 1 of 92 [1.1%], P=0.8628), 2-year (NA group: 8 of 401 [2.0%], AA group: 0 of 23 [0.0%], and CA group: 2 of 90 [2.2%], P=0.7797), 5-year (NA group: 10 of 348 [2.9%], AA group: 0 of 20 [0.0%], and CA group: 2 of 78 [2.6%], P=0.7400), or overall follow-up (NA group: 18 of 412 [4.4%], AA group: 1 of 23 [4.3%], and CA group: 3 of 95 [3.2%], P=0.8664). Data regarding bradycardia and permanent pacemaker implantation are provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Bradycardia, permanent pacemaker implantation, atrial fibrillation, and mortality after HTX

| Parameter | No use of amiodarone before HTX (n=412) | Acute use of amiodarone before HTX (n=23) | Chronic use of amiodarone before HTX (n=95) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradycardia,^ week 1 after HTX | 9 of 412 (2.2%) | 0 of 23 (0.0%) | 0 of 95 (0.0%) | 0.2695 |

| Bradycardia,^ week 2 after HTX | 3 of 412 (0.7%) | 0 of 23 (0.0%) | 1 of 95 (1.1%) | 0.8644 |

| Bradycardia,^ week 3 after HTX | 4 of 412 (1.0%) | 0 of 23 (0.0%) | 1 of 95 (1.1%) | 0.8894 |

| Bradycardia,^ week 4 after HTX | 3 of 412 (0.7%) | 0 of 23 (0.0%) | 1 of 95 (1.1%) | 0.8644 |

| 30-Day follow-up PPM implantation | 3 of 412 (0.7%) | 0 of 23 (0.0%) | 1 of 95 (1.1%) | 0.8644 |

| 30-Day follow-up occurrence of AF | 56 of 412 (13.6%) | 3 of 23 (13.0%) | 2 of 95 (2.1%) | 0.0065* |

| 30-Day follow-up mortality | 40 of 412 (9.7%) | 3 of 23 (13.0%) | 9 of 95 (9.5%) | 0.8656 |

| 1-Year follow-up PPM implantation | 5 of 405 (1.2%) | 0 of 23 (0.0%) | 1 of 92 (1.1%) | 0.8628 |

| 1-Year follow-up mortality | 88 of 405 (21.7%) | 5 of 23 (21.7%) | 20 of 92 (21.7%) | 1.0000 |

| 2-Year follow-up PPM implantation | 8 of 401 (2.0%) | 0 of 23 (0.0%) | 2 of 90 (2.2%) | 0.7797 |

| 2-Year follow-up mortality | 104 of 401 (25.9%) | 5 of 23 (21.7%) | 22 of 90 (24.4%) | 0.8763 |

| 5-Year follow-up PPM implantation | 10 of 348 (2.9%) | 0 of 20 (0.0%) | 2 of 78 (2.6%) | 0.7400 |

| 5-Year follow-up mortality | 130 of 348 (37.4%) | 8 of 20 (40.0%) | 24 of 78 (30.8%) | 0.5174 |

| Overall follow-up PPM implantation | 18 of 412 (4.4%) | 1 of 23 (4.3%) | 3 of 95 (3.2%) | 0.8664 |

| Overall follow-up mortality | 206 of 412 (50.0%) | 10 of 23 (43.5%) | 38 of 95 (40.0%) | 0.1936 |

Notes:

Bradycardia defined as mean weekly heart rate <60 beats per minute.

Statistically significant (P<0.05).

Abbreviations: HTX, heart transplantation; PPM, permanent pacemaker; AF, atrial fibrillation.

Early posttransplant AF

Within 30 days after HTX, 61 of 530 patients (11.5%) had AF. Patients in the CA group had a significantly lower rate of AF compared to the other 2 groups (NA group: 56 of 412 [13.6%], AA group: 3 of 23 [13.0%], and CA group: 2 of 95 [2.1%], P=0.0065). The distribution of AF between the 3 groups is provided in Table 4.

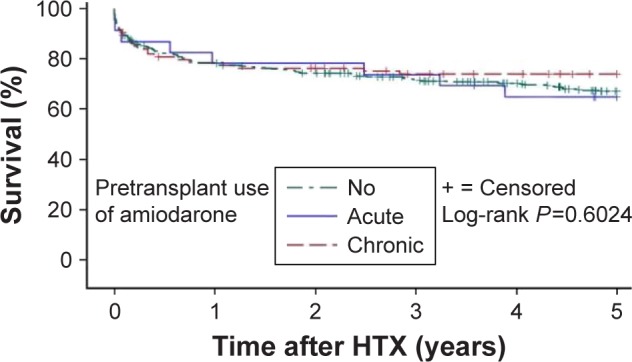

Mortality after HTX

During overall follow-up, 254 patients (47.9%) deceased. We could not discover significant differences between the 3 groups in 30-day (NA group: 40 of 412 [9.7%], AA group: 3 of 23 [13.0%], and CA group: 9 of 95 [9.5%], P=0.8656), 1-year (NA group: 88 of 405 [21.7%], AA group: 5 of 23 [21.7%], and CA group: 20 of 92 [21.7%], P=1.0000), 2-year (NA group: 104 of 401 [25.9%], AA group: 5 of 23 [21.7%], and CA group: 22 of 90 [24.4%], P=0.8763), 5-year (NA group: 130 of 348 [37.4%], AA group: 8 of 20 [40.0%], and CA group: 24 of 78 [30.8%], P=0.5174), or overall posttransplant follow-up mortality (NA group: 206 of 412 [50.0%], AA group: 10 of 23 [43.5%], and CA group: 38 of 95 [40.0%], P=0.1936). The rate of mortality after HTX is shown in Table 4. Furthermore, we could not find a relevant difference in 5-year posttransplant follow-up survival (P=0.6024) in the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. The Kaplan–Meier analysis of 5-year follow-up survival after HTX is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Five-year follow-up survival after HTX (Kaplan–Meier estimator).

Notes: Five-year follow-up survival after HTX of patients without amiodarone therapy before HTX, with acute amiodarone therapy before HTX, and with chronic amiodarone therapy before HTX.

Abbreviation: HTX, heart transplantation.

Discussion

Impact of daily dose and duration of amiodarone on posttransplant survival

The mortality associated with pretransplant amiodarone use has been controversially discussed in the scientific community. Some studies stated an elevated posttransplant mortality,3–5 while others found no difference.6–9

The divergent outcomes regarding pretransplant amiodarone use and mortality may result from differences in daily amiodarone dose. In this study, patients with acute amiodarone use had a mean daily dose of 282.6 mg, and patients with chronic amiodarone therapy a mean daily dose of 225.3 mg. In both groups, no elevated posttransplant mortality was observed. Similarly, Macdonald et al7 found no impaired posttransplant survival in patients with a daily amiodarone dose of 247.0 mg before HTX.

Chin et al16 reported an elevated mortality after HTX in patients with a daily amiodarone dose of 327.0 mg indicating that a higher daily amiodarone dose could be associated with impaired posttransplant survival.

Also, the duration of amiodarone use before HTX might have an impact on posttransplant survival as the duration of amiodarone intake can influence the achievement of steady state as well as its half-life.12,13

Regarding short-term amiodarone use, Chin et al16 divided 38 patients according to the pretransplant duration of amiodarone therapy and found a higher intrahospital mortality rate in patients with amiodarone therapy longer than 4 weeks before HTX.

In contrast, Sanchez-Lazaro et al6 did not find a relevant difference regarding mortality between 371 patients without amiodarone therapy before HTX and 25 patients with a minimum amiodarone therapy of 30 days before HTX.

In the field between acute and chronic amiodarone therapy, Macdonald et al7 detected no statistically significant difference in 1-month mortality between 19 patients with a minimum amiodarone use of 1.5 months before HTX (mean therapy duration of 9 months) and 31 control patients. Regarding chronic amiodarone therapy, Chelimsky-Fallick et al8 reported a comparable 30-day mortality after HTX between 29 patients with a mean pretransplant amiodarone therapy of 11 months and 29 matched patients without amiodarone use before HTX.

The previously mentioned studies focused on short-term mortality after HTX, whereas Blomberg et al4 conducted a 5-year posttransplant survival analysis of patients receiving amiodarone therapy within 3 months before HTX. They found a statistically significant increased mortality in 20 patients receiving amiodarone therapy within 3 months prior to HTX compared to 65 patients without amiodarone use before HTX.4

However, in a recent large amiodarone study of our group,9 we found no increased 5-year mortality after HTX in 74 patients with long-term amiodarone therapy before HTX (≥12 months) compared to 456 patients without long-term amiodarone use before HTX. Additionally, in the current study which focuses on mortality of patients with acute and chronic pretransplant amiodarone use, we found the administration of acute or chronic amiodarone therapy in patients prior to HTX not to be linked to impaired posttransplant survival. There was no statistically significant difference between patients in the NA group, the AA group, and the CA group concerning 30-day, 1-year, 2-year, 5-year, or overall posttransplant follow-up mortality.

Demographics, medication, and echocardiographic features after HTX

Several risk factors may affect mortality after HTX. To mini-mize potential confounders, patients in the NA group were compared to those in the AA group and the CA group. We found no statistically significant differences in recipient data, donor data, transplant sex mismatch, or perioperative data.

However, in terms of principal diagnosis for HTX, significantly fewer patients with cardiac amyloidosis and valvular heart disease were seen in the CA group.

In this study, patients with valvular heart disease were rather young as this group included patients with congenital heart defect such as tetralogy of Fallot or transposition of the great vessels. Especially in younger patients requiring antiarrhythmic treatment, the benefits of amiodarone have to be balanced against potential side effects resulting in fewer prescriptions.21

The limited use of amiodarone in patients with cardiac amyloidosis might result from the little evidence for the safety and benefit of amiodarone against arrhythmias in this cohort.22,23 Additionally, amiodarone therapy due to VT or VF is less frequent as those patients often do not survive the initial arrhythmic disorder and sudden cardiac death is found to be a result of electromechanical dissociation.24,25

Acute rejection episodes have been shown to be associated with impaired survival and to be a risk factor for allograft vasculopathy.26,27 As the occurrence of acute rejection episodes can be affected by the underlying immunosuppressive drug regimen,19,28 we conducted a comparison of the immu-nosuppressive therapy after HTX. There were no statistically significant differences between the 3 groups. Moreover, we could not detect a statistically significant difference between the 3 groups regarding the rate of rejection episodes in the early posttransplant period. Additionally, we analyzed the medication within 30 days after HTX focusing on antiarrhythmic drugs as those can have an impact on heart rate and episodes of bradycardia. Here, we could not find statistically significant differences within the groups regarding beta blocker, calcium channel blocker, or ivabradine reducing the likelihood of potential bias.

As impaired LVEF can cause an increased posttransplant mortality and chronic amiodarone use in patients with congestive heart failure (200 mg per day) has been shown to improve ventricular function,29 echocardiographic features within 30 days after HTX were investigated between the 3 groups. We could not detect any statistically significant differences within the 3 groups (end-diastolic diameters, LVEF, mitral regurgitation, tricuspid regurgitation).

In summary, we could not find larger differences indicating that the 3 groups solely differed statistically in terms of amiodarone use before HTX.

Posttransplant outcomes

Amiodarone therapy can be applied for the management of supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias.30–32 Negative side effects of amiodarone include depression of cardiac chronotropic and dromotropic function including bradycardia, conduction disturbances, and requirement for permanent pacemaker implantation.10,11

Macdonald et al7 observed significantly lower heart rates in posttransplant weeks 1 and 4 along with longer requirement for temporary pacing in patients who had received amiodarone before transplantation. Nevertheless, at 8 weeks after HTX, this difference in heart rates was no further significant, and there was no significant difference in permanent pacemaker implantation (only 1 patient in the control group).7 Similar findings were reported by Chelimsky-Fallick et al.8 Here, patients with pretransplant amiodarone use required more often temporary pacing, and their heart rate was lower at discharge within 1 month after HTX (75±18 vs 86±11 bpm). Again, there was no significant difference in permanent pacemaker implantation (only 1 patient in the amiodarone group).8

Additionally, Chin et al16 observed a significantly lower mean heart rate in the early posttransplant period (103±19 vs 111±15 bpm) in patients with pretransplant amiodarone therapy, although they found no relationship between lower heart rate and mortality. Furthermore, Goldstein et al11 observed a higher percentage of bradycardia during posttransplant week 1 in patients with amiodarone therapy prior to HTX. However, the definition of bradycardia (heart rate <80 bpm) was rather unusual by design, and differences in heart rate were no longer statistically significant between groups during posttransplant week 3.

In contrast to the aforementioned studies, Montero et al33 discovered no significant difference in the percentage of patients with or without bradycardia receiving pretransplant amiodarone therapy. This is in line with a report by Bertolet et al34 finding no association between pretransplant use of amiodarone and a higher incidence of bradycardia after HTX.

Blomberg et al4 found no significant difference between patients with and without pretransplant amiodarone use in terms of temporary pacing or the need for permanent pacemaker implantation. These findings were supported by Sanchez-Lazaro et al6 reporting no statistically significant difference in permanent pacemaker implantation between patients with pretransplant amiodarone use and control patients.

Zieroth et al35 divided patients with amiodarone therapy before HTX into 3 groups depending on their duration of amiodarone intake (<6, 6–12, >12 months). They found no statistically significant association between pretransplant amiodarone use and the requirement for permanent pacemaker implantation after HTX.35

Finally, Woo et al36 found in a large study the underlying surgical technique to be a major predictor of permanent pacemaker implantation after HTX as patients with biatrial anastomosis had a statistically higher likelihood for permanent pacemaker implantation in comparison to patients with bicaval anastomosis. Furthermore, they discovered no significant association between pretransplant amiodarone use and posttransplant permanent pacemaker implantation.36

In the current study, we could not find significant differences between no, acute, and chronic pretransplant amiodarone use regarding heart rates or episodes of bradycardia during posttransplant weeks 1–4. Moreover, requirement for permanent pacemaker implantation did not differ in the short or the long term after HTX between groups.

Hence, given the above-mentioned studies and our own, there seems to be no risk for relevant posttransplant bradycardia or permanent pacemaker implantation in patients with acute or chronic amiodarone exposure before HTX. There are several more reliable causes for rhythm disorders in patients after HTX than pretransplant amiodarone use including sinoatrial node dysfunction due to surgical technique (biatrial HTX technique), cardiac denervation of the allograft with regulatory imbalances (tachycardia/bradycardia), reperfusion injury due to prolonged ischemic time, or the use of additional antiarrhythmic drugs (beta blocker, calcium channel blocker, or ivabradine).1,9,17,35,36

Regarding potential positive effects, pretransplant amiodarone use might be protective against early AF after HTX due to its long half-life.9 Patients suffering from AF are at higher risk for thromboembolic complications such as stroke.37 In addition, patients with early posttransplant AF suffer from reduced survival in comparison to patients with sinus rhythm.17

Several studies have evaluated the effects of prophylactic amiodarone use against AF after cardiac surgery.38–48 Some of them reported a reduced occurrence of AF,38–44 whereas others found no statistically significant differences.45–48 These differences in outcomes might be due to inconsistencies in dosing and administration strategies as some used intravenous amiodarone,38,40,48 others applied oral amiodarone,39,41,43,46,47 and still others used a combination of intravenous and oral amiodarone.42,44,45 However, out comes of prophylactic amiodarone use differed even within administration groups.38–48 Additionally, there seemed to be no difference as to whether prophylactic amiodarone treatment was started preoperatively39,41,43,44,46,47 or peri-/postoperatively.38,40,42,45,48 Hence, data regarding the benefits of prophylactic amiodarone use are inconclusive.

As the above-mentioned studies focused on coronary artery bypass surgery and/or valvular surgery, these results can only be partly adapted to patients after HTX. In our study, patients in the CA group had a significantly lower rate of AF than patients in the NA group or AA group. We could not detect a relevant difference in early posttransplant AF between patients in the NA group or AA group. These results indicate that acute or short-term use of amiodarone before HTX is not sufficient to be protective against early posttransplant AF. Chronic amiodarone use before HTX (>90 days before HTX) only seems to be able to reduce the occurrence of AF after HTX effectively.

Acute and chronic pretransplant amiodarone use

Amiodarone shows multiple pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug–drug interactions.1,32,49,50 Pharmacokinetic interactions may result from interference in the metabolization of one drug by another drug, whereas pharmacodynamic interactions describe the additive or subtractive pharmacological effects of 2 drugs.49

In terms of immunosuppressive drug therapy, amiodarone can cause an increase of calcineurin inhibitors (CsA or TAC) by inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A4 which is responsible for the metabolization of CsA and TAC.1,32 Consequently, close monitoring of calcineurin inhibitor drug trough levels is required in the early posttransplant period. Moreover, amiodarone is also an inhibitor of cytochrome P450 1A2, cytochrome P450 2C9, and cytochrome P450 2D6.1,32,49,50 As a result of these interactions, elevated serum levels of concomitantly administered antiarrhythmic drugs such as digoxin, flecainide, propafenone, phenytoin, procainamide, and quinidine can cause monomorphic or polymorphic VT (torsades de pointes).1,32,49,50 However, though some patients with amiodarone therapy have a prolonged QT interval, severe amiodarone-induced arrhythmias are rather rare.49

Amiodarone is a very lipophilic drug with an extended volume of distribution and a slow clearance rate.2,13–15 Its half-life ranges from only a few hours in patients with a single dose, over a half-life of ~2 months in patients with short-term use, to a half-life of ~4 months in patients with long-term use.13–15 Therefore, even with initial oral loading doses of ~1,000 mg per day and/or intravenous administration, amiodarone may take several weeks to exert its optimal antiarrhythmic effects.9,12,13 Therefore, in patients with pretransplant amiodarone use, the cardiac allograft is exposed to amiodarone to a certain degree due to the above-mentioned properties.1,2 As the amount of amiodarone exposure depends on the duration of its therapy before HTX, this study focused on potential differences in posttransplant outcomes between patients with acute and chronic amiodarone use before HTX.

There were no statistically significant differences between groups in posttransplant medication including the immuno-suppressive regimen, echocardiographic features, heart rates including episodes of bradycardia, or permanent pacemaker implantation. Chronic amiodarone use before HTX was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the occurrence of early posttransplant AF (P=0.0065). In contrast, this effect was not observed in patients with acute amiodarone use before HTX. Hence, these findings suggest that a minimum amiodarone therapy of ~3 months prior to HTX is required to achieve an optimal steady state which can protect the transplanted heart against early posttransplant AF. In terms of mortality after HTX, we discovered no statistically significant differences between groups in 30-day (P=0.8656), 1-year (P=1.0000), 2-year (P=0.8763), 5-year (P=0.5174), or overall posttransplant follow-up mortality (P=0.1936).

In summary, based upon these results and our previous findings of posttransplant outcomes in patients with pre-transplant amiodarone use,9 we could not find an association between impaired survival after HTX and pretransplant amiodarone use regardless of whether acute or chronic amiodarone therapy was administered.

Study limitations

This was a single-center study. Nevertheless, as this study included 530 patients, data are comparable in participant numbers to multicenter studies. Furthermore, contrary to multicenter studies, potential confounders and bias could be minimized by using a similar pre-, peri-, and posttransplant protocol. Secondly, sample sizes were different between the 3 groups which potentially has an influence on results (412 patients were appointed to the NA group, 23 patients to the AA group, and 95 patients to the CA group). However, as there are little data regarding the effects of acute and chronic amiodarone use before HTX on posttransplant outcomes and sample size is limited due to the available number of patients with HTX, even studies covering groups of small sample sizes are of clinical importance. Thirdly, although data were collected prospectively, analysis and evaluation of data were performed retrospectively. Lastly, due to the long follow-up, a potential era effect cannot entirely be excluded.9,17–20

Conclusion

Major concerns about the safety of amiodarone therapy in patients before HTX have been raised.1 Hence, this study was performed to investigate posttransplant outcomes in patients with no, acute, or chronic amiodarone use before HTX.

We found no statistically significant differences between the 3 groups in posttransplant medication including the immunosuppressive regimen, echocardiographic features, heart rates including episodes of bradycardia, or permanent pacemaker implantation. Of notice, only chronic amiodarone use was able to effectively reduce the occurrence of early AF after HTX, whereas acute amiodarone therapy showed no such effect (P=0.0065).

Most importantly, we could not detect relevant differences between the 3 groups in 30-day (P=0.8656), 1-year (P=1.0000), 2-year (P=0.8763), 5-year (P=0.5174), or overall posttransplant follow-up mortality (P=0.1936). Accordingly, based upon these results and our previous findings of posttransplant outcomes in patients with pretransplant amiodarone use,9 there seems to be no association between increased mortality after HTX and pretransplant amiodarone use regardless of whether acute or chronic amiodarone therapy was applied.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG – German Research Foundation) and the University of Heidelberg within the funding program “Open Access Publishing”. We thank Gerda Baumann, Viola Deneke, and Berthold Klein for their assistance and advice.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Jennings DL, Martinez B, Montalvo S, Lanfear DE. Impact of pre-implant amiodarone exposure on outcomes in cardiac transplant recipients. Heart Fail Rev. 2015;20(5):573–578. doi: 10.1007/s10741-015-9490-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giardina EG, Schneider M, Barr ML. Myocardial amiodarone and desethylamiodarone concentrations in patients undergoing cardiac transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;16(4):943–947. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80346-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konertz W, Weyand M, Deiwick M, Scheld HH. Is pretransplant anti-arrhythmic drug therapy a risk factor? Transplant Proc. 1992;24(6):2677–2678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blomberg PJ, Feingold AD, Denofrio D, et al. Comparison of survival and other complications after heart transplantation in patients taking amiodarone before surgery versus those not taking amiodarone. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(3):379–381. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yerebakan H, Naka Y, Sorabella R, et al. Amiodarone treatment prior to heart transplantation is associated with acute graft dysfunction and early mortality: a propensity-matched comparison. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(4 Suppl):S105. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez-Lazaro IJ, Almenar L, Martinez-Dolz L, et al. Does amiodarone influence early mortality in heart transplantation? Transplant Proc. 2006;38(8):2537–2538. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macdonald P, Hackworthy R, Keogh A, Sivathasan C, Chang V, Spratt P. The effect of chronic amiodarone therapy before transplantation on early cardiac allograft function. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1991;10:743–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chelimsky-Fallick C, Middlekauff HR, Stevenson WG, et al. Amiodarone therapy does not compromise subsequent heart transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20(7):1556–1561. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90450-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rivinius R, Helmschrott M, Ruhparwar A, et al. Long-term use of amiodarone before heart transplantation reduces significantly early post-transplant atrial fibrillation and is not associated with increased mortality after heart transplantation. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:677–686. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S96126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bacal F, Bocchi EA, Vieira ML, et al. Permanent and temporary pacemaker implantation after orthotopic heart transplantation. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2000;74(1):9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein DR, Coffey CS, Benza RL, Nanda NC, Bourge RC. Relative perioperative bradycardia does not lead to adverse outcomes after cardiac transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2003;3(4):484–491. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connolly SJ. Evidence-based analysis of amiodarone efficacy and safety. Circulation. 1999;100(19):2025–2034. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.19.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Somani P. Basic and clinical pharmacology of amiodarone: relationship of antiarrhythmic effects, dose and drug concentrations to intracellular inclusion bodies. J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;29(5):405–412. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1989.tb03352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Latini R, Tognoni G, Kates RE. Clinical pharmacokinetics of amiodarone. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1984;9(2):136–156. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198409020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zipes DP, Prystowsky EN, Heger JJ. Amiodarone: electrophysiologic actions, pharmacokinetics and clinical effects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1984;3(4):1059–1071. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(84)80367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chin C, Feindel C, Cheng D. Duration of preoperative amiodarone treatment may be associated with postoperative hospital mortality in patients undergoing heart transplantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1999;13(5):562–566. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(99)90008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivinius R, Helmschrott M, Ruhparwar A, et al. The influence of surgical technique on early posttransplant atrial fibrillation – comparison of biatrial, bicaval, and total orthotopic heart transplantation. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;13:287–297. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S126869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rivinius R, Helmschrott M, Ruhparwar A, et al. Analysis of malignancies in patients after heart transplantation with subsequent immunosuppressive therapy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;9:93–102. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S75464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helmschrott M, Beckendorf J, Akyol C, et al. Superior rejection profile during the first 24 months after heart transplantation under tacrolimus as baseline immunosuppressive regimen. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:1307–1314. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S68542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helmschrott M, Rivinius R, Ruhparwar A, et al. Advantageous effects of immunosuppression with tacrolimus in comparison with cyclosporine A regarding renal function in patients after heart transplantation. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:1217–1224. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S79343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darby AE, Dimarco JP. Management of atrial fibrillation in patients with structural heart disease. Circulation. 2012;125(7):945–957. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.019935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubrey SW. An update on treatments for amyloid heart disease. Br J Cardiol. 2013;20(3):107. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alkindi S, Almasoud A, Younes A, et al. Increased risk of heart block in patients with cardiac amyloidosis on amiodarone. J Cardiac Fail. 2015;21(8 Suppl):S125. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falk RH. Diagnosis and management of the cardiac amyloidoses. Circulation. 2005;112(13):2047–2060. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.489187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kristen AV, Dengler TJ, Hegenbart U, et al. Prophylactic implantation of cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with severe cardiac amyloidosis and high risk for sudden cardiac death. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5(2):235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radovancevic B, Konuralp C, Vrtovec B, et al. Factors predicting 10-year survival after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24(2):156–159. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.11.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamani MH, Yousufuddin M, Starling RC, et al. Does acute cellular rejection correlate with cardiac allograft vasculopathy? J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23(3):272–276. doi: 10.1016/S1053-2498(03)00189-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grimm M, Rinaldi M, Yonan NA, et al. Superior prevention of acute rejection by tacrolimus vs. cyclosporine in heart transplant recipients – a large European trial. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(6):1387–1397. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamer AW, Arkles LB, Johns JA. Beneficial effects of low dose amiodarone in patients with congestive cardiac failure: a placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14(7):1768–1774. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(21):1–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedersen CT, Kay GN, Kalman J, et al. EHRA/HRS/APHRS expert consensus on ventricular arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11(10):166–196. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siddoway LA. Amiodarone: guidelines for use and monitoring. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(11):2189–2196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montero JA, Anguita M, Concha M, et al. Pacing requirements after orthotopic heart transplantation: incidence and related factors. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1992;11(4 Pt 1):799–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bertolet BD, Eagle DA, Conti JB, Mills RM, Belardinelli L. Bradycardia after heart transplantation: reversal with theophylline. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28(2):396–399. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zieroth S, Ross H, Rao V, et al. Permanent pacing after cardiac transplantation in the era of extended donors. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25(9):1142–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woo GW, Schofield RS, Pauly DF, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of cardiac pacing after cardiac transplantation: an 11-year retrospective analysis. Transplantation. 2008;85(8):1216–1218. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816b677c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hohnloser SH, Pajitnev D, Pogue J, et al. Incidence of stroke in paroxysmal versus sustained atrial fibrillation in patients taking oral anticoagulation or combined antiplatelet therapy: an ACTIVE W Substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(22):2156–2161. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hohnloser SH, Meinertz T, Dammbacher T, et al. Electrocardiographic and antiarrhythmic effects of intravenous amiodarone: results of a prospective, placebo-controlled study. Am Heart J. 1991;121(1 Pt 1):89–95. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90960-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daoud EG, Strickberger SA, Man KC, et al. Preoperative amiodarone as prophylaxis against atrial fibrillation after heart surgery. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(25):1785–1791. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712183372501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guarnieri T, Nolan S, Gottlieb SO, Dudek A, Lowry DR. Intravenous amiodarone for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after open heart surgery: the Amiodarone Reduction in Coronary Heart (ARCH) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34(2):343–347. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giri S, White CM, Dunn AB, et al. Oral amiodarone for prevention of atrial fibrillation after open heart surgery, the Atrial Fibrillation Suppression Trial (AFIST): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;357(9259):830–836. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.White CM, Caron MF, Kalus JS, et al. Intravenous plus oral amiodarone, atrial septal pacing, or both strategies to prevent post-cardiothoracic surgery atrial fibrillation: the Atrial Fibrillation Suppression Trial II (AFIST II) Circulation. 2003;108(Suppl 1):II200–II206. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000087445.59819.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitchell LB, Exner DV, Wyse DG, et al. Prophylactic oral amiodarone for the prevention of arrhythmias that begin early after revascularization, valve replacement, or repair: PAPABEAR: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294(24):3093–3100. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.24.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Budeus M, Hennersdorf M, Perings S, et al. Amiodarone prophylaxis for atrial fibrillation of high-risk patients after coronary bypass grafting: a prospective, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(13):1584–1591. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Butler J, Harriss DR, Sinclair M, Westaby S. Amiodarone prophylaxis for tachycardias after coronary artery surgery: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Br Heart J. 1993;70(1):56–60. doi: 10.1136/hrt.70.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Redle JD, Khurana S, Marzan R, et al. Prophylactic oral amiodarone compared with placebo for prevention of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery. Am Heart J. 1999;138(1 Pt 1):144–150. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maras D, Bosković SD, Popović Z, et al. Single-day loading dose of oral amiodarone for the prevention of new-onset atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery. Am Heart J. 2001;141(5):E8. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.114201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beaulieu Y, Denault AY, Couture P, et al. Perioperative intravenous amiodarone does not reduce the burden of atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing cardiac valvular surgery. Anesthesiology. 2010;112(1):128–137. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c61b28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamreudeewong W, DeBisschop M, Martin LG, Lower DL. Potentially significant drug interactions of class III antiarrhythmic drugs. Drug Saf. 2003;26(6):421–438. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200326060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freitag D, Bebee R, Sunderland B. Digoxin-quinidine and digoxin- amiodarone interactions: frequency of occurrence and monitoring in Australian repatriation hospitals. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1995;20(3):179–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.1995.tb00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]