Abstract

BACKGROUND

To understand the low modern contraceptive prevalence in Cameroon, we reviewed the methods chosen and determined their side effects among patients in an urban setting.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional study at the “Cameroon National Planning Association for Family Welfare (CAMNAFAW) Clinic” in Yaoundé. Data were processed by SPSS software version 20.0 for Windows, and all tests were considered statistically significant at P < .05.

RESULTS

Of the 1180 women sampled, the most chosen methods were as follows: depot medroxy progesterone acetate: 72.1% (787 of 1091), followed by oral combined contraceptives: 21.3% (232 of 1091), subcutaneous implants: 3.2% (35 of 1091), and intrauterine contraceptive devices: 1.9% (21 of 1091). A hundred and forty two (14.5%) of the 977 women received at least once (revisits) at the Center, reported at least one side effect. Irregular vaginal bleeding was the most frequent side effect: 44.6% (84 of 188 total documented side effects). Side effects were most common among users of subcutaneous implants: 28% (7 of the 25 implant users).

CONCLUSIONS

Prescription of contraceptives should reflect not only the desire of couples but also the side effects associated with each method. This would optimize observance and adherence, consequently decreasing the failure rate.

Keywords: Modern, contraceptive choice—side effects, women, family planning, Cameroon

Background

Birth control, also known as contraception and fertility control, is a method or device used to prevent pregnancy.1 Planning, making available, and use of birth control is called family planning (FP).2,3 The choice of contraceptive methods by couples is one of the key issues in reproductive rights and reproductive health. The International Conference on Population and Development held in Cairo in 1994 emphasized that reproductive health includes the right of men and women to be informed and to have access to safe, effective, affordable, and acceptable methods of FP of their choice, as well as other methods of their choice for regulation of fertility which are not against the law.4 Palmore and Bulatao in 1989 argued that at the top of the funnel, many methods are listed, and moving downward the relevant factors are divided into 4 groups: technology and cost, contraceptive supplies, sociocultural factors, and personal preferences including side effects.5

Modern contraceptive method is defined by Hubacher D and Trussell J as a product or medical procedure that interferes with reproduction from acts of sexual intercourse. The methods that do not fit under the definition of modern can alternatively be labeled as “nonmodern methods” (such as traditional, natural, physiological, and others).6

Several factors influence the choice of contraceptive method: mode of action, use, efficacy, reversibility, safety, side effects, cost and accessibility, and motivation of the method. According to the 2011 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) conducted in Cameroon, 94.4% of women knew about contraceptive methods. Among all women, the prevalence rate is 23.7% for all methods, 16.1% for modern methods, and 7.6% for traditional methods, whereas as concerns married women, the prevalence of modern methods is 14.4%.7 The Cameroon National Planning Association for Family Welfare (CAMNAFAW) provides a complete suite of sexual and reproductive health services since 1987: intrauterine devices (IUDs), implants (levonorgestrel [LNG]), depot medroxy progesterone acetate (DMPA) also called injectables, combined oral contraceptives (COC), progesterone-only contraceptives (POP), emergency contraceptive pills, and condoms. Condoms are given systematically to all users, and distributing machines for male condoms are available.

Given that few studies have evaluated the contraceptive choices in Cameroon, we conducted this study to review the contraception practice among patients attending the Yaoundé CAMNAFAW clinic. Specifically, we sought to determine the contraceptive methods chosen by the patients and to identify their side effects.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study at the CAMNAFAW health centre of Yaoundé (Republic of Cameroon) over a period of 6 months (November 1, 2010–April 30, 2011). Our study population was made up of files of the patients (men and women) who have used any FP method at CAMNAFAW from November 1, 2010 to April 30, 2011 (6 months). The files of all old and new patients (men and women) recorded at study site to have used FP services during that period were included, and we excluded files of all the patients with very incomplete data.

The sample size was calculated using the Lorenz formula N = p (1 − p) (Zα/d),2 where N = sample size, p = national prevalence of modern contraceptive use in Cameroon which is 16.1% (DHS 2011), Zα = the value of Z corresponding to α in a bilateral situation. Taking α to be 0.05, the Fisher and Yates tables give a Zα value of 1.96, d = degree of precision = 0.05. Using this formula, we got a minimal sample size of 207 patients but, to increase the power of our results, we used a sample size of 1180. The sampling was consecutive. Data were retrieved from the FP registers and files of the patients who have used any FP method during the study period and reported on a pretested data collection sheet. For statistical analysis, data were entered into an Excel sheet and later uploaded into SPSS version 20.0 for Windows. Prior to analyses, all continuous data were tested for normality using histogram plots and tests for skewness and kurtosis to justify use of parametric or nonparametric statistical tests. Univariate analyses of continuous variables were presented as frequencies, mean values, and standard deviations. χ2 tests were used to test for statistical significance as well as for differences between proportions. A difference between mean values of continuous variables when compared between groups was done with using multiple analyses of variance. All test statistics were 2-sided and considered statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

Of the 1183 participants, only 3 (0.25%) were men. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive patients represented 11 (1.0%) of the 1140 clients for who HIV tests were done. For further analysis, we excluded the 3 men seen at the Center were excluded and we considered only women (1180).

General characteristics of study sample

The general characteristics of our population are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics by patient type (new or old).

| VARIABLE | NEW PATIENTS | OLD PATIENTS (REVISITS) | P VALUE | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Total | 153 (13.3) | 998 (86.7) | 1151 (100) | |

| Age, y | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 27.94 ± 6.55 | 30.18 ± 7.00 | <.001 | 29.89 ± 6.99 |

| Age | ||||

| 10–19 | 8 (5.2) | 36 (3.6) | .001 | 44 (3.8) |

| 20–25 | 59 (38.6) | 239 (24.0) | 298 (26.0) | |

| 26–44 | 83 (54.2) | 686 (68.9) | 769 (67.0) | |

| ⩾45 | 3 (2.0) | 34 (3.4) | 37 (3.2) |

Note. Data on patient type (old/new case) missing for 32 cases (2.7%). Data on patient type missing for 185 women.

The ages of the patients varied from 14 to 58 years with a mean of 29.89 ± 6.99 years. The age group from 26 to 44 years was the most represented with 67% (769 of 1151 whose ages were report) of cases.

FP methods used

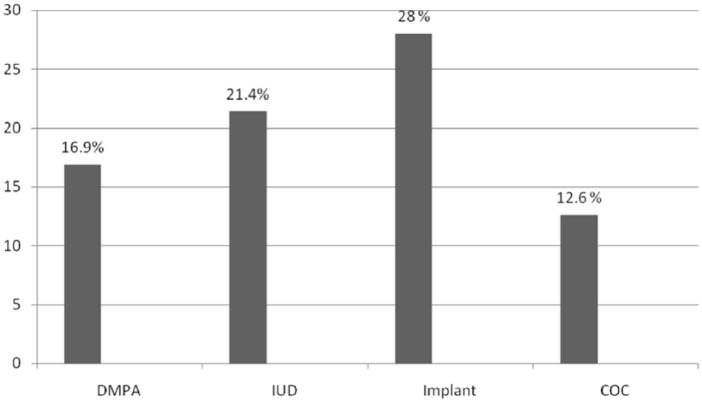

The different FP methods used are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methods of family planning used by the clients (n = 1091). COC indicates combined oral contraceptives; DMPA, depot medroxy progesterone acetate; ECP, emergency contraceptive pills; IUD, intrauterine device; POP, progesterone-only contraceptives.

The most chosen methods were DMPA, COC, and implants (Jadelle or Norplant), with, respectively, 72.1%, 21.3%, and 3.2% respectively.

Distribution of participants following age and type of FP method

The choice of contraceptive method with respect to age group is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of participants following age and type of family planning methods.

| AGE, Y | TOTAL | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13–19 | 20–25 | 26–44 | ⩾45 | ||||

| Methods | IUD | n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 19 (2.6) | 1 (3.0) | 21 (1.9) |

| DMPA | n (%) | 32 (78.0) | 223 (77.4) | 510 (70.0) | 22 (66.7) | 787 (72.1) | |

| Implants | n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) | 31 (4.3) | 2 (6.1) | 35 (3.2) | |

| COC | n (%) | 8 (19.5) | 59 (20.5) | 157 (21.5) | 8 (24.2) | 232 (21.3) | |

| POP | n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) | 4 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.5) | |

| ECP | n (%) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.6) | |

| Others | n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.3) | |

| Total | N (%) | 41 (100.0) | 288 (100.0) | 729 (100.0) | 33 (100.0) | 1091 (100.0) | |

Abbreviations: COC, combined oral contraceptives; DMPA, depot medroxy progesterone acetate; ECP, emergency contraceptive pills; IUD, intrauterine device; POP, progesterone-only contraceptives.

Adolescents in our sample mainly used DMPA which is an injectable progesterone. Young adults (20-25 years old) as well preferred injectables. Adults aged 26 to 44 years preferred rather IUDs and implants.

Contraceptive Side Effects

Side effects experienced by the patients

Side effects experienced by the patients are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Side effects reported by the patients.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Presence of side effects | |

| Yes | 142 (14.53) |

| No | 835 (85.47) |

| Total | 977 (100) |

| Type of side effectsa | |

| Irregular vaginal bleeding | 84 (44.6) |

| Amenorrhea | 41 (22.8 |

| Lower abdominal pain | 19 (10.6) |

| Weight gain | 18 (10.0) |

| Headache | 10 (5.6) |

| Nausea | 3 (1.7) |

| Change in sex drive | 2 (1.1) |

| Breast pain | 1 (0.6) |

| Mood changes | 1 (0.6) |

| Raised blood pressure | 1 (0.6) |

Some patients had more than 1 type of side effects. In all 188 side effects were reported.

Of 977 patients, 142 (14.53%) had at least one side effect.

Irregular vaginal bleeding, amenorrhea, lower abdominal pain, weight gain, and headache in order of decreasing frequency were the most frequent of all reported side effects, respectively in, 84 (44.6%), 41 (22.8%), 19 (10.6%), 18 (10%), and 10 (5.6%) of the 188 side effects reported in all.

Prevalence of side effects with respect to choice of contraceptive

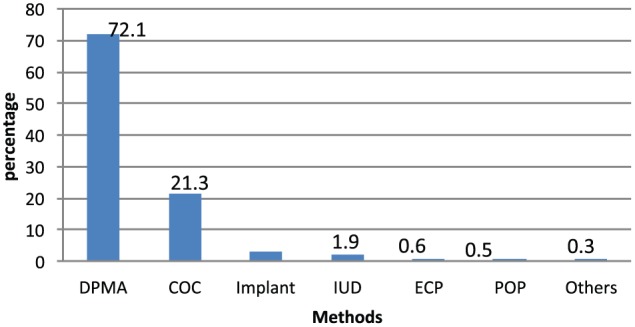

The prevalence of side effects with respect to choice of contraceptive is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of side effects with respect to choice of contraceptive. COC indicates combined oral contraceptives; DMPA, depot medroxy progesterone acetate; IUD, intrauterine device; implant, levonorgestrel.

Reported Side effects were most reported with use of implant (28.0%) followed by IUD (21.4%) and injectable contracetive (16.9%) and least in the patients using POP and emergency contraceptive pills.

Side effects with respect to method of FP

Side effects with respect to the method of FP used are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Side effects with respect to method of family planning.

| SIDE EFFECTS | METHOD | ENTIRE STUDY SAMPLE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMPA | IUD | IMPLANT | COC | POP | ECP | |||

| Irregular bleeding | n (%) | 56 (50.5) | 1 (33.3) | 3 (42.9) | 6 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 66 (46.5) |

| Weight gain | n (%) | 9 (8.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (10.6) |

| Headache | n (%) | 3 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 4 (19.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (5.6) |

| Nausea | n (%) | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.1) |

| Amenorrhea | n (%) | 27 (24.3) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 30 (21.1) |

| Breast pain | n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Lower abdominal pain | n (%) | 12 (10.8) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (11.3) |

| Mood changes | n (%) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Change in sex drive | n (%) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4)) |

| Total | N (%) | 111 (78.2) | 3 (2.1) | 7 (4.9) | 21 (14.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 142 (100.0) |

Abbreviations: COC, combined oral contraceptives; DMPA, depot medroxy progesterone acetate; ECP, emergency contraceptive pills; IUD, intrauterine device; POP, progesterone-only contraceptives.

Irregular bleeding, amenorrhea, lower abdominal pain, and weight gain were the most frequent side effects. They were found, respectively, in 66 (46.6%), 30 (21.1%), 16 (11.3%), and 15 (10.6%) patients of 142.

The most frequent reported side effects in DMPA users were: irregular bleeding: 56 (50.5%), amenorrhea: 27 (24.3%), lower abdominal pain: 12 (10.8%), and weight gain: 9 (8.1%).

The most frequent reported side effects in COC users were: irregular bleeding: 7 (28.6%), weight gain: 7 (28.6%), headache: 4 (19.0%), and amenorrhea: 2 (9.5%).

As for implants, the most frequent reported side effects were: irregular bleeding: 3 (42.9%) and lower abdominal pain: 2 (28.6%).

The most frequent side effects with IUD use were irregular bleeding 1: (33.3%), amenorrhea: 1 (33.3%), and lower abdominal pain: 1 (33.3%). No side effect was reported at the time of the study, by patients who used POP or emergency pills.

Discussion

Of the 1183 participants, only 3 were men and 1180 were women. The 2 possible reasons explaining this could be that either FP is conceived by Cameroonians as a woman’s responsibility or our FP units are not men friendly. However, CAMNAFAW has distributing machines for male condoms, and this may explain why many men do not come for counseling as they just stop outside to collect their condoms from the machines and no records are kept on those using condoms.

The HIV-positive patients represented just 1.00% of all the clients. These may reflect the poor access and adherence of HIV-positive patients to FP services.

General characteristics of study sample

The ages of the patients varied from 14 to 58 years with a mean of 29.89 ± 6.99 (Table 1). The age group between 26 and 44 was the most represented with 67% (769 of 1151) of cases (Table 1). This age group in Cameroon is mostly made up of working class sexually active women who want to avoid pregnancy and be professionally productive. Adolescents (from 10 to 19 years) were the third most represented group with 3.8% (45 of 1151) of the participants (Table 1). These results tie with findings of the 2011 DHS which showed a very low contraceptive use in this age group and high fertility rate (15% for both age groups).7

FP methods used

Considering the FP methods used, we found that CAMNAFAW does not provide all modern FP methods. However, they do counsel the patients on all modern methods of FP, and for those that cannot be offered at the clinic, patients are referred to competent services.

The most chosen methods were injectables (DMPA), COC, and implants, with, respectively, 72.1% (787 of 1091), 21.3% (232 of 1091), and 3.2% (35 of 1091) of all methods (Figure 1). In total, 21 of 1091 (1.9%) patients used IUDs; 7 (0.6%) used emergency contraceptive pills; whereas 0.5% (6 of 1091) used progesterone-only pills. A similar trend was observed in the 2011 DHS.7 A similar study of a smaller study sample of 123 clients in Nigeria in 2007,8 found different results with 26 clients (21.1%) on pills, 19 (15.5%) used IUD, 17 (13.8%) used injectables, and 35 (28.5%) used condom. The general trend in the developed world is the usage of more pills, whereas in sub-Saharan Africa, the trend puts injectables ahead.9,10 The work by Thembelihle11 2010 in a South African population had a predominance of injectables (58%). One of the reasons for high proportion of injectables use is that it is an “invisible” method12,13 of contraception that can be used secretly without male partners finding out. This emanates from unequal power dynamics between men and women in Cameroon. Women can use injectables without having to negotiate contraceptive use with their male partners.

Distribution of participants following age and type of FP method

Adolescents in our sample mainly used DMPA which is the injectable progesterone (Table 2). Findings from the 2011 DHS were similar.7 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends long-acting reversible contraceptive methods for adolescents (IUDs and implants in association with condoms for double protection) saying that they are safe and appropriate.14,15

Young adults (20-25 years old) used more injectable contraceptives compared with other methods. The DHS 2011 report confirms our findings.7

Adults aged 26 to 44 years also preferred injectables. This is similar to the findings of the DHS 2011 which shows that this age group uses more injectables.7

Contraceptive side effects

Side effects experienced by the patients

The overall prevalence of side effects was 14.53%: 142 patients of 977 had at least one side effect (Table 3). Irregular vaginal bleeding, amenorrhea, lower abdominal pain, weight gain, and headache were the most frequent side effects with, respectively, 84 (44.6%), 41 (22.8%), 19 (10.6%), 18 (10%), and 10 (5.6%) of all 188 total side effects reported.

Prevalence of side effects with respect to choice of contraceptive

Side effects were most reported prevalent with use of implant (28.0%) followed by IUD (21.4%) and least in the patients using POP and emergency contraceptive pills. Depot medroxy progesterone acetate had the third most common complaints (16.9%) (Figure 2).

Side effects with respect to method of FP

Irregular bleeding, amenorrhea, lower abdominal pain, and weight gain were the most frequent side effects. They were found, respectively, in 66 (46.6%), 30 (21.1%), 16 (11.3%), and 15 (10.6%) patients of 142 (Table 4).

The most frequent reported side effects with DMPA use were as follows: irregular bleeding: 56 (50.5%), amenorrhea: 27 (24.3%), lower abdominal pain: 12 (10.8%), and weight gain: 9 (8.1%).

COC reported irregular bleeding (28.6%) followed by, weight gain (28.6%), headache (19.0%) and amenorrhea (9.5%).

No side effect was noticed for the patients who used POP or emergency pills.

The least side effect noted was increase in blood pressure noted in one patient. Side effects were most reported with use of LNG implant (28.0%) followed by IUD (21.4%) and least in the patients using POP and emergency contraceptive pills. Depot medroxy progesterone acetate, the most used (in 72.3% of patients), had the third most common complaints (16.9%). This probably explains the high adherence by the patients to this method.

All these findings corroborate with findings in literature on side effects of hormonal contraception.16,17

These findings tie with documented side effects of OCPs and injectables18,19 where changes in libido are expected more with progesterone-containing contraceptives.

Conclusions

It follows from our findings that the most used methods of contraception by the patients of CAMNAFAW clinic are DMPA followed by pills, implants, and IUDs. We strongly recommend that FP programs should target adolescents separately because they are most at risk of unplanned pregnancies, and the use of contraceptives should reflect not only the desire of couples but also the side effects associated with each method. This would optimize the observance and adherence, consequently decreasing failure rate.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the administration of the study site (CAMNAFAW) as well as the staff of CAMNAFAW clinic for their support during data collection. They sincerely thank the reviewers of the article for their valuable contributions.

Footnotes

PEER REVIEW: Six peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 777 words, excluding any confidential comments to the academic editor.

FUNDING: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions

TTY conceived the study, participated in the study design, data collection, and drafting and editing of the manuscript. FYF and MEN participated in the study design, data collection and analyses, and drafting and editing of the manuscript. FN contributed to the design of the study and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures and Ethics

Ethical clearance and administrative authorization of the study were obtained from the management board of CAMNAFAW and its ethical committee. All the information obtained from the FP registers remained confidential. The authors have read and confirmed their agreement with the ICMJE authorship and conflict of interest criteria. The authors have also confirmed that this article is unique and is not under consideration or published in any other publication, and that they have permission from rights holders to reproduce any copyrighted material. The external blind peer reviewers report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Medical definition of birth control. MedicineNet. http://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=53351. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- 2.Oxford English Dictionary . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; Jun, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) Family planning. Health topics. WHO; http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/family_planning/en/. Retrieved March 28, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajeretnam T. Sociocultural determinants of contraceptive method choice in Goa and Kerala, India. J Fam Welfare. 2000;46:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rele JR, Kapour PN, Khan ME. Determinants of and consequences of contraceptive method choice in India. In: Butatao RA, Palmore JA, Wards SE, editors. Choosing a Contraceptive Method Choice in Asia and United States. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1995. pp. 192–211. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hubacher D, Trussell J. A definition of modern contraceptive methods. Contraception. 2015;92:420–421. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institut National de la Statistique (INS) et ICF. International . Enquête Démographique et de Santé et à Indicateurs Multiples du Cameroun 2011. Calverton, MD: INS et ICF International; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oyedokun AO. Determinants of contraceptive usage: lessons from women in Osun State, Nigeria. J Human Soc Sci. 2007;1:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Population Reference Bureau Family planning worldwide 2008 Data Sheet. http://www.prb.org/pdf08/fpds08.pdf.

- 10.World Health Organization Family planning/contraception. Fact sheet no. 351. [Accessed September 23, 2016]. http://who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs351/en/. Updated December 2016.

- 11.Thembelihle B. Factors Influencing Contraceptive Use and Unplanned Pregnancy in a South African Population [MpH thesis] Johannesburg, South Africa: University of Witwatersrand; 2010. p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Southern African Regional Poverty Issues in the financing of family planning Services in Sub-Saharan Africa. [Accessed September 20, 2010]. http://www.popline.org/node/522993.

- 13.Trussell J, Guthrie KA. Choosing a contraceptive: efficacy, safety, and personal considerations. In: Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates W, Kowal D, Policar M, editors. Contraceptive Technology. New York, NY: Ardent Media; 2007. pp. 19–47. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee opinion no. 539: adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:983–988. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182723b7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trussell J, Guthrie K. Lessons from the contraceptive CHOICE project: the Hull long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) initiative. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2015;41:60–63. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2014-100944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Family Planning. A Global Handbook for Providers. http://apps.who.int/iris/bit-stream/10665/44028/1/9780978856373_eng.pdf. Revised 2011 Update.

- 17.Bonny AE, Secic M, Cromer B. Early weight gain related to later weight gain in adolescents on depot medroxyprogesterone acetate. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:793–797. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820f387c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dinger J, Minh TD, Buttmann N, Bardenheuer K. Effectiveness of oral contraceptive pills in a large U.S. cohort comparing progestogen and regimen. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:33–40. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820095a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovalevsky G, Barnhart K. Norplant and other implantable contraceptives. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2001;44:92–100. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200103000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]