Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To demonstrate experimentally that an assistive technology (AT) intervention improves older AT users’ activity performance and satisfaction with activity performance, and decreases their caregivers’ sense of burden.

DESIGN

A delayed intervention, randomized control trial. Baseline data were collected on 44 community-dwelling, AT user-caregiver dyads in Vancouver, British Columbia, and Montreal, Quebec. The primary outcome measures for AT users were the satisfaction and accomplishment scales from the Assessment of Life Habits. The primary outcome measure for caregivers was the Caregiver Assistive Technology Outcome Measure which assessed burden associated with dyad-identified problematic activities.

RESULTS

Compared to the delayed intervention group, assistance users in the immediate intervention group reported significantly increased satisfaction with activity performance (p<.001), and improved accomplishment scores (p =.014). Informal caregivers in the immediate intervention group experienced significantly decreased burden with the dyad-identified, problematic activity (p=.013). Participants in the delayed intervention group experienced similar benefits following the intervention.

CONCLUSIONS

This is the first experimental study to demonstrate that the provision of AT decreases caregiver burden. If confirmed and extended by subsequent research, the findings have significant policy and practice implications and may enable health-care providers to advocate for improved access to AT provision and the related follow-up services.

Keywords: assistive technology, informal caregiving, older adults, community dwelling

Almost two-thirds of Americans who are over the age of 65 and have an activity of daily living disability use assistive technology.1 Assistive technology (AT) includes “any item, piece of equipment, or product system, whether acquired commercially, modified or customized, that is used to increase, maintain, or improve functional capabilities of individuals with disabilities.”2 Not surprisingly, AT use increases with age, almost doubling each decade after the age of 65.3

A principal reason for prescribing AT for older people is that it improves their ability to perform activities of daily living. Although high quality evidence is limited, two experimental studies have demonstrated that the provision of problem-specific AT and environmental modifications can attenuate functional decline.4,5

Another primary, yet largely unexamined justification for providing AT is that it reduces users’ dependence on human assistance, especially assistance from informal caregivers – i.e., friends, family, and community members who provide unpaid assistance to recipients who are ill or disabled. Informal caregivers provide four times as much assistance as formal ones.6 Their replacement value has been estimated to be $450 billion annually in the United States.7 A recent systematic review found no experimental evidence demonstrating the impact of AT on users’ caregivers8; however, several studies in this review with cross-sectional or pre-post designs suggested that AT use may decrease caregivers’ physical and psychological (e.g., stress, anxiety etc.) burden.

Given the limited research on the impact of AT on users and their informal caregivers, we conducted a preliminary experimental study to examine the effectiveness of a novel AT updating and tune-up intervention on user-caregiver dyads. The study had two main hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 1

Following an intervention that increases the appropriateness of existing AT (i.e., an AT “tune-up”) or provides new AT (i.e., “updating”), older community dwelling AT users will report increased accomplishment and satisfaction with performance of dyad-identified, problematic activities.

-

Hypothesis 2

Following the intervention, informal caregivers will report decreased caregiving burden.

METHODS

This exploratory, multi-site study used an open-label, delayed intervention, randomized control design. This design was selected because of a concern about ethical equipoise. Given evidence suggesting that AT inventions are beneficial to assistance users and caregivers, we felt it would be untenable to use a control group that was denied the intervention. The study was approved by the ethics boards at each site and registered with clinicaltrials.gov (registration number NCT00927706).

Participants

The study occurred in the residences of participants living in non-institutional environments in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada and in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Enrolled assistance users needed to have a physical disability, be over 65 years of age, and receive more than 2 hours of care per week from an informal caregiver. Assistance users with cognitive impairments that prevented them from responding to the questionnaires and providing informed consent were excluded from the study. Informal caregivers included relatives, friends, neighbors, and community members, but excluded individuals working as volunteers for care provision organizations.

In the Vancouver area, participants were recruited via letters of invitation sent by the local homecare provider (Vancouver Coast Health), newspaper and newsletter advertisements, and presentations at local caregiving conferences. In the Montreal region, participants were recruited through Health and Social Services Centers (Centres de santé et de services sociaux). Recruitment occurred from June 2009 until March 2011.

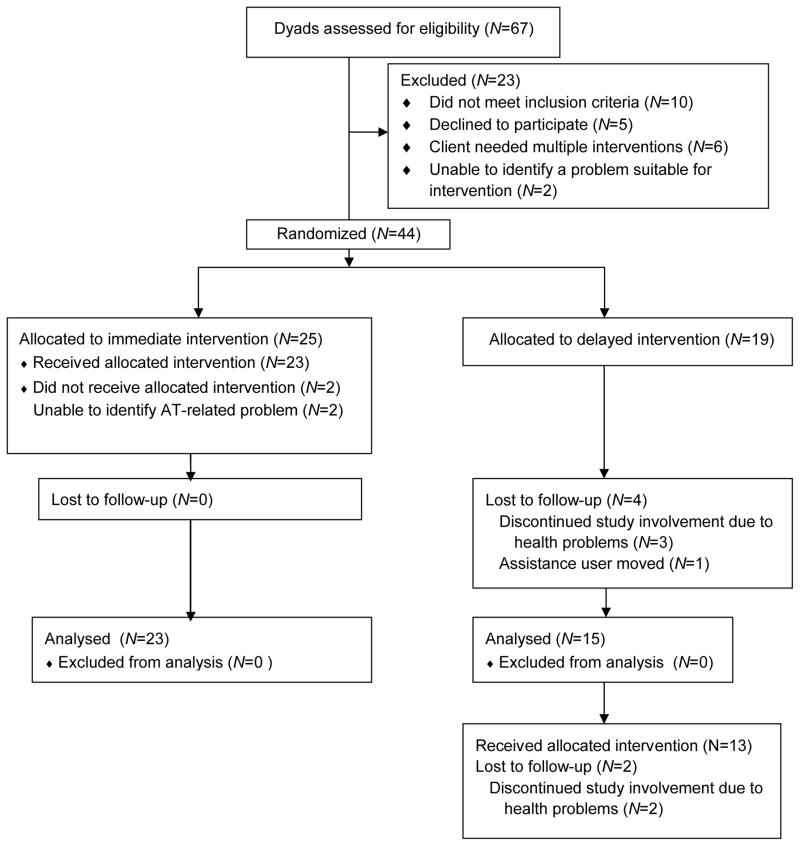

As noted in Figure 1, 67 dyads were screened for eligibility, and 44 were randomized to either the immediate intervention group (N=25) or the delayed intervention group (N=19) using a web-based random number generator (www.random.org). At six weeks, 38 dyads remained in the study, 23 in the immediate intervention group and 15 in the delayed intervention group. Thirteen dyads in the delayed group received the intervention.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram

Intervention

This 6-week long intervention included four components:

A detailed home assessment that reviewed the forms of assistance, technological and human, currently being used;

Identification of a dyad-selected activity that was perceived to be physically or psychologically problematic by both the assistance user and informal caregiver and was amenable to AT intervention;

Recommendations for possible changes in the care recipient’s AT; and

Negotiation of an AT updating and tune-up intervention plan jointly with the care recipient and his or her caregiver. This could include provision of new AT (i.e., “AT updating”), as well as additional training with current AT or repair of existing AT (i.e., “an AT tune-up”). The treatment protocol included a detailed description of each component and was operationalized into 20 discrete steps (available upon request).

To ensure the AT updating and tune-up intervention was safe, feasible, and relevant to the targeted individuals, we developed it using an iterative process involving consultation with clinicians, assistance users, and caregivers. The final version was pretested with two dyads.

The intervention was delivered by three registered occupational therapists who were trained by the Montreal study coordinator to deliver the intervention. Each of the therapists had over 20 years of clinical experience. To encourage consistent administration of the intervention (i.e., treatment fidelity), therapists documented the provision of each component and recorded the corresponding completion date. Adverse events were also documented.

As depicted in Figure 1, the intervention was provided to the immediate intervention group following the administration of the outcome measures. It was provided 6 weeks later to the delayed intervention group, which received the intervention following a second administration of the baseline measures. The outcome measures were re-administered to both groups 22 weeks after provision of the intervention.

Outcome Measures for Assistance Users

Two primary outcome measures were chosen for assistance users. Both were derived from the Assessment of Life Habits (Life H).9 The first uses a 5-point scale to capture the self-rated satisfaction with performance of the dyad-selected activity; the second uses a 10-point personal care/accomplishment sub-scale to capture the self-rated level of accomplishment for that activity as seen in table 1. For example, a score of 6 indicates it is performed with difficulty with AT or adaptation and a score of 7 indicates the activity is performed with difficulty, but with no assistance. This sub-scale of the Life-H, which contains items that are most similar to the dyad-identified activities in the current study, has a high test-retest reliability (Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) = .95).9

Table 1.

Life-H Accomplishment Scale Scoring

| Score | Difficulty | Assistance |

|---|---|---|

| 9 | No difficulty | No help |

| 8 | No difficulty | Technical aids or adaptations |

| 7 | With difficulty | No help |

| 6 | With difficulty | Technical aids or adaptations |

| 5 | No difficulty | Human assistance |

| 4 | No difficulty | Human assistance and aids or adaptations |

| 3 | With difficulty | Human Assistance |

| 2 | With difficulty | Human assistance and aids or adaptations |

| 1 | Accomplished by substitute | |

| 0 | Too difficult to perform |

The Individually Prioritized Problem Assessment (IPPA)10,11 was used as a secondary outcome measure for assistance users. The IPPA captures self-rated task difficulty using a 5-point rating scale, in which 5 equals too much difficulty and 1 equals no difficulty at all. The IPPA has been reported to be more sensitive to change following provision of AT than the Sickness Impact Profile and EuroQol.12

Outcome Measures for Caregivers

The primary outcome for caregivers was the frequency of physical and psychological burden associated with the dyad-identified activity. This was measured using the activity-specific portion of the Caregiver Assistive Technology Outcome Measure (CATOM).13 The CATOM is based on a conceptual model of outcomes for caregivers of AT use.14 Its activity-specific section includes questions about physical assistance, verbal cuing, caregiver pain, and worry about the possibility of user or caregiver injury. This activity-specific section contains 14 items that are each rated on a 5-point response scale. The item ratings are summed to produce a total section score, with higher scores indicating decreased perceived burden. In the current study, the internal consistency of this section of the measure was a=.733.

The overall burden section of CATOM was used as a secondary outcome measure. This section of CATOM includes 4 items that are rated using the same 5-point response scale. The scores for these items are summed to produce a total section score. In the current study, the internal consistency of this section CATOM was a=.778.

The ranges of standardized measures are presented in the first column Table 1. Unless otherwise noted, higher scores on the measures indicate increasing amounts of the construct measured. All measures were available in French and English.

Socio-demographic and Clinical Variables

We collected socio-demographic data about participants’ age; sex; level of education; relationship between members of the dyad; e.g., spouse or parent-child; cohabitation; assistance user diagnosis; and amount of informal caregiving received. The assistance user’s cognitive status was measured using the Mini-Mental State Exam, a widely used cognitive screening test with good reliability (mean Kappa value across all items =0.97).15 The assistance user’s attitudes toward technology was measured using the Attitudes Toward Assistive Device Scale, which has an internal consistency of 0.61.16 The assistance user’s level of independence with mobility, self-care, communication, cognition, and instrumental activities of daily living was assessed using the Functional Autonomy Measure (FAM), a 29- item measure (ICC=0.95).17 Caregivers’ and users’ health statuses were measured using the visual analogue scale from the EuroQol (ICC=0.90).18

Data Collection

Trained raters collected the study data. Measures were administered to both groups at baseline and 6 weeks and to the delayed intervention group at 12 weeks.

Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as means and categorical variables were described as proportions. To assess baseline similarity between groups, we compared the experimental and delayed groups using t-tests for continuous data and Chi-square for nominal data. To quantify treatment fidelity, we calculated the percentage of steps in the treatment protocol that were completed. Given the exploratory nature of the research and funding limitations, we hoped to recruit 60 dyads into the study.

Scores on the outcome measures were compared between treatment groups over time (time * group) using an intention to treat analysis. We performed a repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) to analyze baseline and week 6 outcome data, with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction to address issues of sphericity. Paired t-tests were used to examine changes in outcome measures following the intervention in the delayed intervention group. Diagnostic procedures were used to ensure that statistical assumptions were not violated beyond the tolerance of the test. Statistical analyses were performed using Predictive Analytics Software 18.0. An alpha value of .05 was selected for primary and secondary outcomes.

We conducted an analysis to determine if the effect of the intervention varied across sites. For this analysis, results of the immediate intervention and delayed intervention groups were combined, and a RM-ANOVA was performed using site as a between-subjects factor.

To explore the relationship between caregiver and assistance user outcomes we calculated correlations between change scores for activity specific burden (CATOM items 1–14) and both the assistance user IPPA and Life-H scores using the combined file.

RESULTS

Table 2 describes the baseline characteristics for the delayed intervention and immediate intervention groups. There were no significant differences between the groups at baseline. Participants in the delayed intervention and immediate intervention groups had a mean age of 83 years and 82 years, respectively. Osteoarthritis was the most common primary diagnosis in both groups. In both groups, most caregivers were women and most were spouses.

Table 2.

Assistance Users’ and Caregivers’ Background Characteristics and Outcome Measures at Baseline (N=44)

| Assistance user background characteristics (range) | Delayed Group | Immediate Group | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| mean ±SD or number (%) | mean ±SD or number (%) | ||

| Age | 83.1±6.4 | 82.1±7.4 | .634 |

| Sex (female) | 11(58) | 12(48) | .515 |

| Years of education | 10.9±4.8 | 10.2±5.1 | .695 |

| Primary Diagnosis | .925 | ||

| Osteoarthritis | 11(58) | 15(60) | |

| Cardiorespiratory | 1(5) | 2(8) | |

| Neurological | 6(31) | 6(25) | |

| Other | 1(5) | 2(8) | |

| MMSE (0–30) | 26.6±3.3 | 26.3±4.5 | .845 |

| Function (FAM) (−87–0) | −24.9±10.1 | −22.5±10.5 | .459 |

| Perceived Health (EuroQOL (0–100) | 52.1±23.5 | 56.3±18.6 | .523 |

| Attitudes towards Assistive Devices (12–60) | 40.5±4.7 | 40.6±5.6 | .930 |

| Assistance user outcomes | |||

| Difficulty (1–5) | 3.6±0.8 | 3.5±1.1 | .785 |

| Satisfaction (1–5) | 2.7±1.0 | 2.4±1.1 | .327 |

| Accomplishment (0–9) | 3.5±2.2 | 4.1±2.4 | .450 |

| Caregiver Background Characteristics | |||

| Age | 74.4±13.5 | 67.6±12.3 | .089 |

| Sex (female) | 11(58) | 19(76) | .202 |

| Relationship | .218 | ||

| Spouse | 15(79) | 14(56) | |

| Child | 3(16) | 10(40) | |

| Other | 1(5) | 1(4) | |

| Cohabitation with assistance user | 16(84) | 19(76) | .504 |

| Years of education | 12.2±3.0 | 13.8±3.4 | .099 |

| Hours of care provision | 11.6±12.9 | 18.1±22.4 | .265 |

| Perceived Health (0–100) | 63.9±44.1 | 80±16.6 | .117 |

| Caregiver outcomes | |||

| CATOM items 1–14 (14–70) | 54.7±8.2 | 51.7±11.3 | .351 |

| CATOM items 15–18 (4–20) | 16.8±3.3 | 15.0±4.3 | .158 |

Note: EuroQOL= FAM= Functional Autonomy Measure, MMSE=Mini Mental Status Exam, CATOM=Caregiver Assistive Technology Outcome Measure, SD=standard deviation

The dyad selected activities targeted for intervention included bathing (N=12, 29%), indoor/outdoor mobility (N=11, 27%), transferring (N=4, 10%), dressing (N=3, 7%), toileting (N=3, 7%), meal preparation/eating (N=3, 7%) and other (N=5, 12%).

Table 3 describes the results of the RM-ANOVA comparing the findings between baseline and six weeks. Compared to assistance users in the delayed intervention group, those in the immediate intervention group experienced significantly improved accomplishment (partial Eta Sq2=.155) and satisfaction with performance (partial Eta Sq2=.354) and significantly decreased difficulty with their dyad-selected activities (partial Eta Sq2=.217) over the first 6 weeks. Caregivers experienced significantly decreased burden with the dyad-selected activities (partial Eta Sq2=.160), but not with their overall burden.

Table 3.

Comparisons of Outcomes for Participants in the Immediate and Delayed Intervention Groups between Baseline and 6 weeks (N=38)

| Construct | Group | Baseline (Mean±SD) | 6 weeks (Mean±SD) | Time*Group (T*S): F(sig) | T*S Partial Eta Sq2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| User difficulty | I | 3.5±1.2 | 2.1±.8 | 9.7(.004) | .217 |

| D | 3.5±.7 | 3.3±1.0 | |||

| User satisfaction | I | 2.4±1.1 | 4.1±1.1 | 19.7(<.001) | .354 |

| D | 2.6±1.0 | 2.5±1.1 | |||

| User accomplishment | I | 4.0±2.3 | 5.4±2.3 | 6.6 (.014) | .155 |

| D | 3.7±2.3 | 3.5±2.2 | |||

| Caregiver activity specific burden | I | 51.6±11.6 | 61.3±7.2 | 6.8 (.013) | .160 |

| D | 55.1±8.7 | 55.3±8.8 | |||

| Overall caregiver burden | I | 14.8±4.2 | 15.3±4.4 | 0(.995) | 0 |

| D | 17.0±2.8 | 17.4±2.6 |

Note: CATOM= Caregiver Assistive Technology Outcome Measure, D=delayed, I= Immediate, SD=standard deviation, Sig=significance, Sq2=squared

Table 4 displays the paired t-test scores comparing pre-post changes in outcome measures for the delayed intervention group. That group experienced significantly improved satisfaction with performance and accomplishment with the dyad-selected activities. Difficulty scores exhibited nearly significant improvement (p=.051). Caregivers experienced significantly decrease burden with the dyad-selected activities, but not with their overall caregiving burden.

Table 4.

Changes in Outcomes for the Delayed Intervention Group (N=13)

| Pre-Tx | Post-Tx | Mean change | Standard Deviation | t | Sig. (2- tailed) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assistance Users | ||||||

| Difficulty | 3.2 | 2.4 | −.8 | 1.4 | 2.2 | .051 |

| Accomplishment | 3.7 | 5.8 | 2.1 | 2.9 | −2.6 | .024 |

| Satisfaction | 2.5 | 3.6 | 1.1 | 1.6 | −2.3 | .041 |

| Caregivers | ||||||

| CATOM (items 1–14) | 57.2 | 61.5 | 4.3 | 3.7 | −4.2 | .001 |

| CATOM (items 15–18) | 17.1 | 16.9 | −.2 | 2.3 | .2 | .817 |

Sig=significance, Tx=intervention

Effects of the intervention on the outcome measures did not vary significantly across sites. For users the interaction terms were not significant for perceived difficulty (F=.003, p= .960), accomplishment (F=.122, p=.729), and satisfaction (F=.185, p=.670). Nor were the interaction terms significant for the caregivers’ activity specific burden (F=1.466, p=.234) and overall burden (F=.713, p=.404).

Examining correlations of change scores before and after the intervention (when results from the delayed and immediate intervention groups were combined) indicated that changes in activity specific caregiver burden were moderately correlated with changes in assistance user outcomes. Caregiver’s activity-specific burden (CATOM items 1–14) decreased significantly as users’ perceived difficulty (IPPA) decreased (r=−.405, p=.016) and users’ accomplishment (Life-H) increased (r=.402 p=.015). Changes in satisfaction with activity performance (Life-H) approached significance (r=.325, p=.056).

On average, 89% of the 20 steps comprising the AT intervention were completed for participants. Completion of individuals steps ranged from 78% to 100% except for step 3 (i.e., perform baseline assessment), which was completed by 62% of therapists. This omission generally occurred for participants who already had a pre-existing baseline assessment as part of their medical charts. No adverse events were reported.

DISCUSSION

This is the first experimental study to examine the impact of an AT-focused intervention on both assistance users and their informal caregivers. The results indicate that the AT-focused intervention had a tangible, substantive impact on device users and their informal caregivers. As hypothesized, assistance users in the immediate and delayed intervention groups both evinced significantly greater satisfaction and increased accomplishment performing the dyad-selected activity. Perceived task difficulty was significantly diminished for the immediate intervention group and approached significance for the delayed intervention group, the non-significance of the latter perhaps owing to its underpowered sample size. These results are in keeping with other experimental studies indicating that AT interventions can improve functional outcomes for users.4,5

As hypothesized, caregivers in both the immediate- and delayed-intervention groups experienced significant decreases in their activity-specific caregiving burden. The immediate- and delayed-intervention groups did not exhibit pre-post differences in overall burden. The latter findings are unsurprising given the targeted nature of the AT intervention, which focused on a single caregiving-related activity.

These results are consistent with those of non-experimental studies suggesting that AT provision can make caregiving tasks easier, safer, and less time consuming.8 The data provide empirical support for the interdependence of caregiver and assistance user outcomes. Specifically, decreases in activity-specific caregiver burden were associated with increases in assistance-user accomplishment and decreases in assistance user difficulty. In addition, the correlation between changes in caregiver burden and changes in assistance-user satisfaction approached statistical significance. It seems likely that increased accomplishment and decreased difficulty scores reflect the extent to and manner in which the device is being used to perform the targeted activity. This may simultaneously lead to decreasing caregivers’ psychological and physical burden. Thus, users may be motivated to use AT to 1) decrease their own task performance difficulty and increase their accomplishment, 2) decrease caregiver burden, or 3) improve outcomes simultaneously for both. Caregivers may encourage device use for similar reasons.

The findings suggest that the scope of cost-benefit analyses of AT impact should be expanded to include the “costs” of caregiver burden that are mitigated by practitioner-recommended AT. Given the enormous contributions of informal caregivers6,7 and concerns about potential burnout19 and a rapidly aging population,20 this cost-benefit consideration is not inconsequential.

The data also provide nascent support for the validity of the CATOM tool. The CATOM’s internal consistency values (Cronbach’s alpha=0.733 and 0.778) are not unexpected for a tool that seeks to measure an inherently broad-based construct such as caregiver burden. Given the activity-specific nature of the AT intervention, the pre-post changes in activity-specific burden and pre-post consistency of overall burden both support CATOM’s construct validity. The statistical significance of the former and the statistical non-significance of the latter suggest that both sections of CATOM are measuring what they were designed to measure. Lastly, the statistically significant correlations between caregiver and user-reported outcomes suggest convergent validity with existing measures of constructs that are logically linked.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be noted. Randomization of participants into the immediate and delayed intervention groups was based on a larger sample size estimate. As we were unable to meet our recruitment targets, there were unequal numbers of participants in immediate and delayed intervention groups. Despite this limitation, however, there were no significant differences between the groups at baseline. Multiple comparisons increased the likelihood of a Type I error, and small sample sizes may have led to Type II errors for some comparisons. Additionally, the lack of blinding and the subjective nature of the outcome measures may have increased the likelihood of a social desirability bias.21 The current study design did not allow us to ascertain the contribution made by each component of the AT intervention (e.g., systematic encouragement of both care recipient and caregiver involvement in goal selection, AT provision, or training) to the measured outcomes. Perhaps including caregivers as active partners in the AT provision process may have a direct effect on the burden they perceive. Unknown as well is how the present results might differ from the outcomes of customary care that may or may not include the informal caregiver in the intervention process. It seems likely that a more comprehensive, holistic intervention might have a stronger effect on both user and caregiver outcomes than the single-activity focus of the present intervention.

Future Research

This research can inform future studies in at least three respects. First, use of a delayed intervention control group made participant recruitment especially challenging. It meant that dyads assigned to that group had to wait 6 weeks before receiving the intervention. Subsequent studies might benefit from using other designs, e.g., one in which the control group receives services in accord with contemporary standards of care. Second, additional research is needed to identify the active ingredients that contributed to the success of the intervention, which in the current study included the timely provision of free AT, explicit involvement of the informal caregiver throughout the intervention process, and use of a formalized AT provision treatment protocol. Finally, there is also a question about what factors predict caregivers’ degree of benefit. Is it based primarily on users’ motivation for using the AT or how they actually perform with it?

CONCLUSION

This is the first experimental study to demonstrate the impact that an AT updating and tune-up intervention on users and their informal caregivers. The results support the provision of AT to help reduce caregivers’ perceptions of task-specific burden, which is important in light of the stress that they experience. If these findings are confirmed by future research, they will suggest changes in the way that AT is prescribed and funded.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The United States National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research supported this work via a grant to the Consortium on Assistive Technology Outcomes Research (CATOR, http://www.outcomes.org/, grant #H133A060062). The Canadian Institutes of Health Research provided financial support for Dr. Mortenson’s participation. Support was also provided to Dr. Demers by the Fonds de recherche en santé du Québec. We would like to acknowledge Michelle Plante, Denise McCabe, and Louise Roy for their help with participant recruitment.

Footnotes

- Demers L, Mortenson W, Plante M, Raymond M-H & CATOR. Impacts des aides techniques auprès des usagers et de leurs proches-aidants: Résultats préliminaires. Congrès International Francophone de Gériatrie et Gérontologie, Nice, France, October 19–21, 2010.

- Mortenson WB, Demers L, Roy L, Lenker J, Jutai J, Fuhrer M, DeRuyter F. Efficacy of a user-caregiver assistive technology intervention: Preliminary results. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists National Conference, May 26–29, 2010.

- Mortenson, W.B., Demers, L., Jutai, J., Fuhrer, M.J., Lenker, J. & DeRuyter, F. How assistive technology use by older individuals with disabilities impacts their informal caregivers. International Federation on Ageing. 11th Global Conference on Ageing. Prague, Czech Republic, May 28 − June 1, 2012.

Disclosures:

Financial disclosure statements have been obtained, and no conflicts of interest have been reported by the authors or by any individuals in control of the content of this article.

Sources of Support: This work was supported by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (grant # H133A060062) and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (grant # 232262-1). Personal financial support for Dr. Mortenson was provided by a CIHR post-doctoral fellowship in the area of Aging and Mobility from the Institute of Aging.

Financial disclosure: We certify that no party having a direct interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer any benefit on us or on any organization with which we are associated. We certify that all financial and material support for this research are clearly identified in the title page of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Agree EM, Freedman VA. Incorporating assistive devices into community-based long-term care: An analysis of the potential for substitution and supplementation. J Aging Health. 2000;12:426–450. doi: 10.1177/089826430001200307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assistive Technology Act of 1998. Pub.L. 105–394, 112 Stat. 3627, S. 2432, enacted November 13, 1998.

- 3.Cornman JC, Freedman VA, Agree EM. Measurement of assistive device use: Implications for estimates of device use and disability in late life. Gerontologist. 2005;45:347. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson DJ, Mitchell JM, Kemp BJ, Adkins RH, Mann W. Effects of assistive technology on functional decline in people aging with a disability. Assist Technol. 2009;21:208–217. doi: 10.1080/10400430903246068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mann WC, Ottenbacher KJ, Fraas L, Tomita M, Granger CV. Effectiveness of assistive technology and environmental interventions in maintaining independence and reducing home care costs for the frail elderly. A randomized controlled trial. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:210–217. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agree EM, Freedman VA, Sengupta M. Factors influencing the use of mobility technology in community-based long-term care. J Aging Health. 2004;16:267–307. doi: 10.1177/0898264303262623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feinberg L, Reinhard SC, Houser A, Choula R. Valuing the invaluable: 2011 Update –The growing contributions and costs of family caregiving. Washington, DC: American Association of Retired Persons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mortenson WB, Demers L, Fuhrer M, Jutai J, Lenker J, DeRuyter F. How Assistive Technology Use by Individuals with Disabilities Impacts their Caregivers: A Systematic Review of the Research Evidence. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318269eceb. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noreau L, Desrosiers J, Robichard L, Fougeyrollas P, Rochette A, Viscogliosi C. Measuring social participation: reliability of the LIFE-H in older adults with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:346–352. doi: 10.1080/09638280410001658649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wessels R, de Witte L, Andrich R, Ferrario M, Persson J, Oberg B, Oortwijn W, VanBeekum T, Lorentsen O. IPPA, a user-centred approach to assess effectiveness of assistive technology provision. Technol Disabil. 2000;13:105–115. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wessels R, Persson J, Lorentsen O, Andrich R, Ferrario M, Oortwijn W, VanBeekum T, Brodin H, de Witte L. IPPA: Individually Prioritised Problem Assessment. Technol Disabil. 2002;14:141–145. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Persson J. An overview of the Effectiveness of Assistive Technology Services project: effectiveness of assistive technology and services. In: Anogianakis G, Bühler C, Soede M, editors. Advancement of Assistive Technology. Amerstam, Netherlands: IOS Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Depa M, Demers L, Fuhrer M, Jutai J, Lenker J, DeRuyter F. A tool for measuring assistive technology outcomes as experienced by caregivers. Can J Occup Ther (Conf Supplement) 2009;76:54. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demers L, Fuhrer MJ, Jutai J, Lenker J, Depa M, De Ruyter F. A conceptual framework of outcomes for caregivers of assistive technology users. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88:645–655. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181ae0e70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connor DW, Pollitt PA, Hyde JB, et al. The reliability and validity of the mini-mental state in a British community survey. J Psychiatr Res. 1989;23:87–96. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(89)90021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roelands M, Van Oost P, Stevens V, Depoorter AM, Buysse A. Clinical practice guidelines to improve shared decision-making about assistive device use in home care: A pilot intervention study. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55:252–264. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desrosiers J, Bravo G, Hebert R, Dubuc N. Reliability of the revised functional autonomy measurement system (SMAF) for epidemiological research. Age Ageing. 1995;24:402–406. doi: 10.1093/ageing/24.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Badia X, Monserrat S, Roset M, Herdman M. Feasibility, validity and test–retest reliability of scaling methods for health states: The visual analogue scale and the time trade-off. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:303–310. doi: 10.1023/a:1008952423122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egbert N, Dellmann-Jenkins M, Smith GC, Coeling H, Johnson RJ. The emotional needs of care recipients and the psychological well-being of informal caregivers: Implications for home care clinicians. Home Healthc Nurse. 2008;26:50–57. doi: 10.1097/01.NHH.0000305557.29918.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shrestha LB, Heisler EJ. The changing demographic profile of the United States. Congressional Research Service. :7–5700. RL32701. Downloaded May 15, 2012 from http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL32701.pdf.

- 21.Fisher RJ, Katz JE. Social-desirability bias and the validity of self-reported values. Psychology Marketin. 2000;17(2):105–120. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.