Abstract

Open reading frame 11 (ORF11) is a conserved gammaherpesvirus gene that remains undefined. We identified the product of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV-68) ORF11, p43, as a virion component with a predominantly perinuclear distribution in infected cells. MHV-68 lacking p43 grew normally in vitro but showed reduced lytic replication in vivo and a delay in seeding to the spleen. Subsequent latency amplification was normal. Thus, MHV-68 ORF11 encoded a virion component that was important for in vivo lytic replication but dispensable for the establishment of latency.

The gammaherpesviruses have probably colonized every mammalian species (11) and offer an object lesson in how to persist and remain infectious in a mammalian host. Gammaherpesvirus latency genes, particularly those of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), have been analyzed in some detail. However, latency genes represent only a small fraction of each viral genome, most of which is devoted to lytic replication. The functions of many gammaherpesvirus-specific lytic genes are completely unknown. This is an important gap in our knowledge, since viral transmission depends on lytic gene expression, and without understanding transmission, it is difficult to develop optimal strategies of infection control.

The human gammaherpesviruses, EBV and the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), do not readily enter the lytic cycle in vitro and exhibit very narrow species tropisms in vivo. These limitations upon analysis have made murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV-68), a gammaherpesvirus isolated from free-living rodents (3), a key experimental tool for understanding in vivo gammaherpesvirus gene functions (12, 13, 15). MHV-68 is closely related to KSHV (7, 16). Moreover, despite genetic divergence in latency genes among MHV-68, KSHV, and EBV, many lytic cycle genes show a high level of conservation among all three viruses. Consequently, the study of MHV-68 lytic genes has the potential to define features of in vivo pathogenesis that are broadly relevant to both human pathogens. Here we have addressed the role of MHV-68 open reading frame 11 (ORF11), which has homologs in both KSHV (ORF11) and EBV (Raji LF2).

MHV-68 ORF11 is a late gene (2, 6, 10). KSHV ORF11 has been placed in the kinetic class of primary lytic genes (8). We identified p43, the MHV-68 ORF11 gene product, as a component of virions, both as native protein and when fused to cyan-fluorescent protein (CFP). ORF11 was dispensable for viral lytic replication in vitro but contributed to lytic replication in vivo, implying a host interaction function. It was not required for the establishment of latency, consistent with the idea that this process is essentially independent of lytic replication.

Generation of ORF11-deficient viruses.

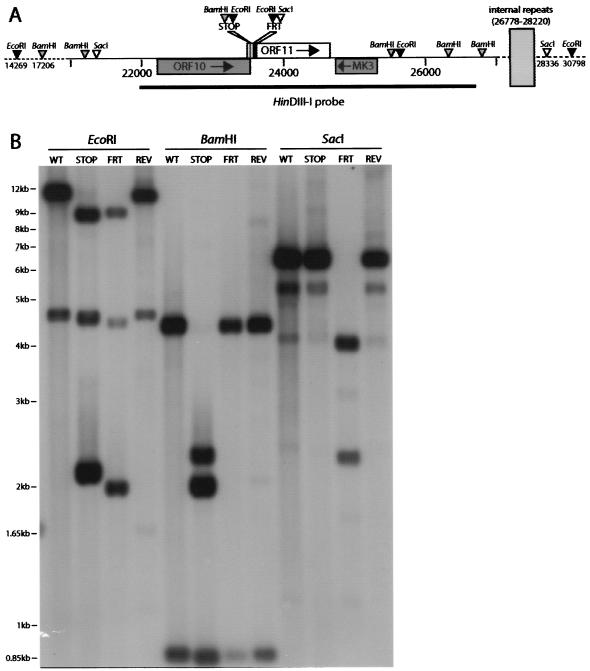

We generated two ORF11 mutants using an MHV-68 bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) (1) (Fig. 1A). First, we ligated the complementary oligonucleotides 5′GAGTGGCAGACCCTCTAGCTAGGATCCGAATTC and 5′GAATTCGGATCCTAGCTAGAGGGTCTGCCACTC into a blunted NcoI site (genomic coordinate 23503) in a HinDIII-I genomic clone (7). This ligation maintained the overlapping 3′ end of ORF10 and introduced a translational stop site as the 14th amino acid residue of ORF11, as well as diagnostic EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites (underlined). The correct insert orientation was identified by DNA sequencing. Mutant ORF11 (ORF11−STOP) was subcloned into the pST76K-SR shuttle plasmid and recombined into MHV-68 BAC by established protocols (1). We caused the mutant BAC to revert (mutant REV) in a similar way, repairing the ORF11 locus with an unmutated HinDIII-I genomic clone. To make an independent mutant, we used RecE/T recombination to replace genomic coordinates 23548 to 23699 of the MHV-68 BAC with a kanamycin resistance gene (Kanr gene) flanked by flp recombinase target (FRT) sites. The Kanr gene was then excised by transient flp recombinase expression, to leave a single FRT site plus short, flanking plasmid sequences (166 bp in all). The residual insert included diagnostic EcoRI and SacI restriction sites and terminated normal ORF11 translation after 20 amino acid residues (ORF11−FRT). Southern blots (Fig. 1B) confirmed the predicted genomic structure of each virus.

FIG. 1.

Generation of ORF11-disrupted viruses. (A) ORF11 was disrupted near its N terminus, just downstream of the overlapping ORF10 stop codon. In the ORF11−STOP mutant (STOP), an oligonucleotide was inserted into an NcoI site just within ORF10 but was designed so as to reconstitute the ORF10 C terminus and then halt ORF11 translation after 13 amino acid residues (16). The oligonucleotide also introduced diagnostic BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites. In the ORF11−FRT mutant (FRT), a 166-bp insert, incorporating diagnostic EcoRI and SacI restriction sites, replaced 150 bp of the ORF11 coding sequence, changed amino acid residues 21 to 29, and introduced a stop codon as the 30th residue. These mutations were nonoverlapping. (B) Southern blots confirmed the predicted structure of the ORF11−STOP (STOP) and ORF11−FRT (FRT) mutants plus a revertant (REV) of the ORF11−STOP mutant. Viral DNA was digested with EcoRI, BamHI, or SacI as indicated, electrophoresed, and hybridized with a 32P-labeled HinDIII-I probe (genomic coordinates 21965 to 26711) according to standard protocols (4). The predicted EcoRI bands for wild-type (WT) virus were 11,370 plus 5,159 bp. In the ORF11−STOP mutant, the 11,370-bp band was cut into 9,234- plus 2,136-bp fragments; in the ORF11−FRT mutant, the 1,1370-bp band was cut into 9,429- plus 1,939-bp fragments. The 5,159-bp band incorporates the left-hand internal repeats, which are variably lost in the BAC without obvious consequence for viral fitness (1). Thus, this band lies between 5,159 and 4,300 bp in BAC-derived viruses. The predicted BamHI bands for wild-type virus were 4,295 plus 845 bp. In the ORF11−STOP mutant, the 4,295-bp band was cut into 2,304- plus 1,911-bp fragments. The predicted SacI band for wild-type virus was 6,953 bp. Again, this band was somewhat smaller because of some loss of internal-repeat copies. In the ORF11−FRT mutant, the 6,953-bp SacI fragment was cut into 4,636-bp (this band incorporates the internal repeats and so was somewhat smaller) plus 2,315-bp fragments.

Replication of ORF11-deficient viruses.

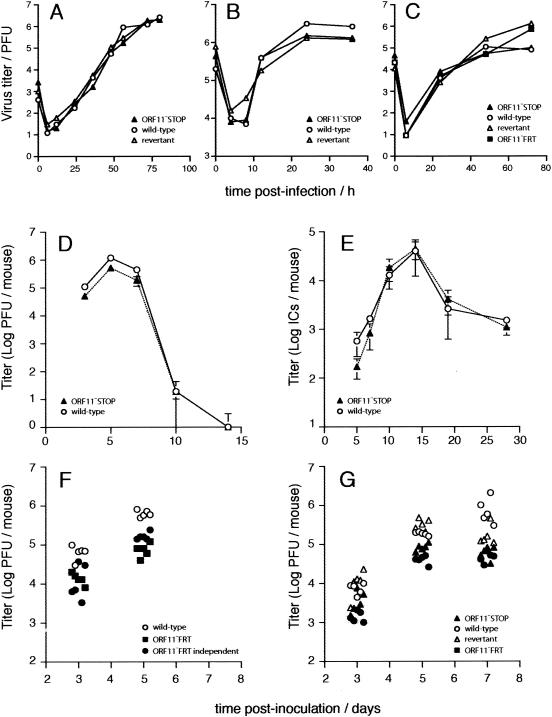

Neither the ORF11−STOP nor the ORF11−FRT mutant showed an in vitro growth deficit (Fig. 2A to C). Thus, ORF11 was dispensable for viral lytic replication in both BHK-21 cells and murine embryo fibroblasts. In contrast, there was a small but significant lytic replication deficit after intranasal infection of mice (Fig. 2D). The initial seeding of latent virus to the spleen was also reduced (Fig. 2E, days 5 and 7), consistent with less lytic replication. However, latency amplification was unimpaired (Fig. 2E). This lack of impairment compensated for the seeding deficit and allowed the virus to achieve a normal latent load by day 10 of infection. The in vivo lytic replication deficit of the ORF11−STOP mutant was reproduced with two independently derived ORF11−FRT mutants (Fig. 2F) and in both C57BL/6J and BALB/c mice (Fig. 2G). A revertant of the ORF11−STOP mutant showed no significant replication deficit compared to the replication of the wild type (Fig. 2G).

FIG. 2.

Growth of ORF11-disrupted viruses in vitro and in vivo. (A) BHK-21 cells were infected at a low multiplicity of infection (0.01 PFU/cell) with wild-type, ORF11−STOP, or revertant virus as indicated. The growth of virus with time was monitored by plaque assay on BHK-21 cells. (B) Growth in BHK-21 cells after a high multiplicity of infection (5 PFU/cell) was monitored by plaque assay as described for panel A. (C) Growth in murine embryo fibroblasts after a low multiplicity of infection (0.01 PFU/cell). Again, the titer of virus was determined by plaque assay on BHK-21 cells. We also assayed the ORF11−FRT mutant. (D) Six- to 8-week-old female BALB/c mice were infected intranasally with 2 × 104 PFU of virus as previously described (12). The titers of infectious virus in lung homogenates were determined by plaque assay on mouse embryonic fibroblasts (5). Each bar shows mean titers ± standard errors of the means of results for five individual mice. ORF11−STOP virus titers were significantly reduced compared to those of the wild type at days 3, 5 (P < 0.005 by Student's t test), and 7 (P < 0.03) postinfection. (E) Latent virus in spleens was measured by infectious center assay (5). Preformed infectious virus, measured by infectious-center assay of freeze-thawed samples, was always <0.1% of the infectious center titer (data not shown). The ORF11−STOP virus showed significantly reduced initial seeding to the spleen at days 5 and 7 (P < 0.02). Titers thereafter were equivalent to that of the wild type. Again, each point shows the mean ± standard error of the mean of results for five mice per group. ICs, infectious centers. (F) Infectious virus titers in lungs were measured by plaque assay after intranasal infection of BALB/c mice with two independently derived ORF11−FRT mutants. Each point represents the result for one mouse. Both mutants showed a significant reduction in titers compared to those of the wild-type virus at days 3 and 5 (P < 0.005). (G) C57BL/6Jmice were infected intranasally with 2 × 104 PFU of ORF11−STOP, the revertant, ORF11−FRT or wild-type MHV-68 as indicated. Infectious virus in lung homogenates was measured by plaque assay. Each point represents the result for one mouse. Both ORF11 mutants showed a significant reduction in titer compared to that of the wild-type virus (P < 0.05 at each time point), whereas the revertant did not.

Characterization of the ORF11 gene product.

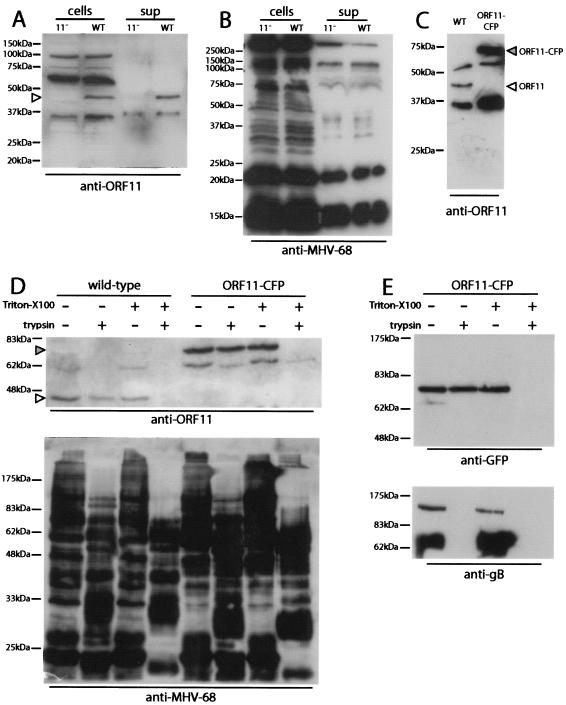

An ORF11-specific polyclonal serum was raised (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) by immunizing rabbits with amino acid residues 137 to 308 of ORF11 fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST). Immunoblotting of infected cell lysates with this serum identified a 43-kDa ORF11-specific band (p43) (Fig. 3A). The size of the band was consistent with the predicted size of the ORF11 gene product (42.5 kDa). We also tagged ORF11 in situ with CFP to give a predicted 70-kDa fusion protein. To do this, we used PCR to generate 1.2-kb genomic recombination flanks on either side of the 3′ end of ORF11, inserting EcoRI and SalI restriction sites immediately upstream of the ORF11 stop codon. The CFP coding sequence was then cloned into these sites, thereby fusing CFP to the C-terminal lysine residue of ORF11 via a short linker. The ORF11-CFP fusion construct was recombined into a wild-type MHV-68 BAC by using the pST76K-SR shuttle plasmid, as described above. The ORF11-CFP virus showed no growth deficit in vitro (data not shown). Its BAC cassette GFP-coding sequence (1) was removed by viral passage through 3T3-CRE cells (14). Native and CFP-tagged p43 proteins were detectable in purified wild-type and ORF11-CFP virions, respectively (Fig. 3B). Since p43 is not predicted to be a component of the viral capsid and lacks a transmembrane domain, it is most likely to be a component of the MHV-68 tegument.

FIG. 3.

Identification of the ORF11 gene product. (A) Cell-associated (cells) and supernatant (sup) stocks of ORF11−STOP (11−) and wild-type (WT) MHV-68 were immunoblotted with rabbit anti-ORF11-GST serum. The ORF11-specific product of approximately 43 kDa is indicated by an arrowhead. The predicted size of the ORF11 gene product is 42.5 kDa. (B) The same virus stocks were immunoblotted with rabbit anti-MHV-68 serum as a loading control. This process did not detect an ORF11-specific band. (C) Purified virions were immunoblotted with rabbit anti-ORF11-GST serum as described for panel A. Virions were recovered from supernatants of virus-infected cells by high-speed centrifugation (38,000 × g, 90 min) and then resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline, sonicated, layered over 5 to 15% Ficoll gradients, centrifuged again (30,000 × g, 90 min), recovered as a distinct band, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and stored at −70°C. In the ORF11-CFP virus, ORF11 is tagged in situ with CFP at its C terminus. The predicted size of the ORF11-CFP fusion protein is 70 kDa. (D) Purified virions were lysed or not lysed by adding Triton X-100 to a final concentration of 1% and incubating the virions on ice for 30 min. All samples were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C with or without 20 μg of trypsin per ml. Digestion was stopped by adding protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics) and returning the samples to ice. The samples were then boiled in Laemmli's buffer, resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and immunoblotted with anti-ORF11 or anti-MHV-68 rabbit sera as indicated. The open arrowhead indicates the native ORF11 band; the filled arrowhead indicates the ORF11-CFP fusion band. (E) ORF11-CFP virions were treated as described for panel D but immunoblotted with either an anti-GFP rabbit serum (Molecular Probes) to detect the ORF11-CFP fusion protein or the anti-gB monoclonal antibody T7H9 (9). gB in virions is predominantly cleaved from a 120-kDa precursor, and T7H9 recognizes the 65-kDa C-terminal fragment (9).

We confirmed that ORF11 lies within the virion envelope by trypsin digestion of purified virions (Fig. 3D and E). Wild-type and ORF11-CFP virions were treated or not treated with Triton X-100 to dissolve the virion membrane and then digested or not digested with trypsin. The virions were then immunoblotted for ORF11 or with an anti-MHV-68 serum (Fig. 3D). The anti-MHV-68 serum showed a substantial digestion of virion proteins by trypsin with or without Triton X-100, whereas ORF11 and ORF11-CFP were digested only when Triton X-100 was present. We then repeated this experiment with the ORF11-CFP virus and used an anti-GFP serum to detect ORF11. This process confirmed that ORF11-CFP was resistant to trypsin unless the virion membrane was first removed, whereas glycoprotein B (9) was digested regardless of whether the virion membrane was present or not.

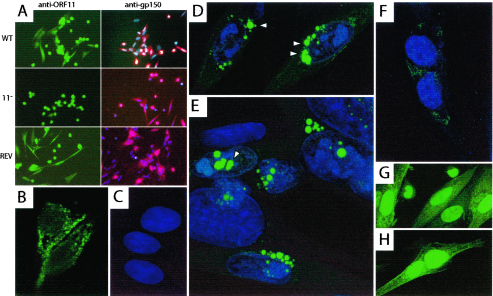

Immunofluorescence with the anti-p43 serum showed ORF11-specific cytoplasmic staining (Fig. 4A and B). There was also nonspecific staining of some dead and dying cell nuclei (Fig. 4A). We used the ORF11-CFP virus as an independent means of localizing p43, without the complication of background staining (Fig. 4C to F). Unmodified GFP, expressed from the MHV-68 BAC cassette (1), showed a predominantly nuclear localization in infected cells (Fig. 4G and H). In contrast, ORF11-CFP was perinuclear. At 24 h postinfection, cyan fluorescence was concentrated in perinuclear spots (Fig. 4D and E). This appearance was consistent with the immunofluorescence data and presumably reflected p43 accumulating at sites of virion assembly. There was weaker cyan fluorescence on infected-cell surfaces, probably from p43 in mature virions that were attached to the outer surface of the plasma membrane (Fig. 4D). CFP spots that appeared to be within the nucleus (Fig. 4D) appeared to be within protrusions of the perinuclear space rather than the nuclear substance itself. The cyan fluorescence at 6 h postinfection (Fig. 4F) was relatively weak, consistent with ORF11 being a late gene of MHV-68, but was again perinuclear in distribution.

FIG. 4.

p43 localization in MHV-68-infected cells. (A) BHK-21 cells were infected overnight with the wild type (WT), ORF11−STOP (11−), or REV as indicated. After fixation in methanol (−20°C, 5 min) and permeabilization with 0.1% Tween 20, the cells were stained with rabbit anti-ORF11 serum plus Alexa488-coupled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) serum (green) or a gp150-specific monoclonal antibody plus Alexa594-coupled goat anti-mouse IgG serum (red). The nuclei of gp150-stained cells were counterstained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (blue). Fluorescence was visualized on an Olympus microscope with a Hamamatsu digital camera. The anti-ORF11 serum stained the nuclei of some dead or dying cells nonspecifically but showed ORF11-specific cytoplasmic staining. (B) Perinuclear fluorescence in cells infected with wild-type virus and stained with anti-ORF11 serum plus Alexa488-coupled goat anti-rabbit IgG serum, visualized on a Leica confocal microscope. (C) Uninfected BHK-21 cells whose nuclei are stained with with DRAQ-5 (blue). (D) BHK-21 cells 24 h after infection with the ORF11-CFP virus, with cyan fluorescence (green) concentrated in perinuclear spots (arrowheads). (E) ORF11-CFP-infected BHK-21 cells as described for panel D. Arrowheads indicate CFP spots that appeared to be intranuclear but were probably infoldings of the perinuclear space. (F) BHK-21 cells 6 h after infection with ORF11-CFP virus. (G) BHK-21 cells 6 h after infection with wild-type MHV-68 expressing unconjugated GFP under the control of a human cytomegalovirus IE1 promoter as part of the left-end BAC cassette. (H) BHK-21 cells infected with GFP+ virus as described for panel G but after 24 h.

Speculation on p43 function.

Virion tegument proteins such as p43 allow herpesviruses to modulate immediately the state of the newly infected host cell, before the viral genome reaches the nucleus. This modulation is crucial to the outcome of infection. The range of documented tegument protein functions is consequently extensive, and it is as yet unclear where p43 fits into this scheme. In vivo lytic replication, where ORF11 was important, clearly represents a more stringent test of viral fitness than replication in immortalized cell lines, where ORF11 was redundant. The in vitro-in vivo discrepancy suggested that p43 might have a host interaction function; possibilities include immune evasion, apoptosis inhibition, and promotion of DNA replication in quiescent cells. The importance of the last in viral pathogenesis is seen with MHV-68 thymidine kinase mutants, which show normal in vitro replication and a gross deficiency in in vivo replication (4).

A three- to fivefold decrease in lytic replication might seem rather insignificant for viral fitness, particularly with normal latency establishment. However, the key role for lytic replication probably lies not in primary infection but in reactivation from latency and transmission to new hosts. Despite viral immune evasion, host immunity leaves only a limited window for productive reactivation, so even a threefold reduction in lytic replication would severely reduce long-term infectivity. We are only just beginning to uncover the many host functions that complex viruses such as MHV-68 modulate to maximize the infectious particle yield.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Medical Research Council grants G108/462 and G9800903 and project grant 059601 from the Wellcome Trust. P.G.S. is an MRC/Academy of Medical Sciences Clinician Scientist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler, H., M. Messerle, M. Wagner, and U. H. Koszinowski. 2000. Cloning and mutagenesis of the murine gammaherpesvirus 68 genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome. J. Virol. 74:6964-6974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn, J. W., K. L. Powell, P. Kellam, and D. G. Alber. 2002. Gammaherpesvirus lytic gene expression as characterized by DNA array. J. Virol. 76:6244-6256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaskovic, D., M. Stancekova, J. Svobodova, and J. Mistrikova. 1980. Isolation of five strains of herpesviruses from two species of free living small rodents. Acta Virol. 24:468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman, H. M., B. de Lima, V. Morton, and P. G. Stevenson. 2003. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 lacking thymidine kinase shows severe attenuation of lytic cycle replication in vivo but still establishes latency. J. Virol. 77:2410-2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Lima, B. D., J. S. May, and P. G. Stevenson. 2004. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 lacking gp150 shows defective virion release but establishes normal latency in vivo. J. Virol. 78:5103-5112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebrahimi, B., B. M. Dutia, K. L. Roberts, J. J. Garcia-Ramirez, P. Dickinson, J. P. Stewart, P. Ghazal, D. J. Roy, and A. A. Nash. 2003. Transcriptome profile of murine gammaherpesvirus-68 lytic infection. J. Gen. Virol. 84:99-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Efstathiou, S., Y. M. Ho, and A. C. Minson. 1990. Cloning and molecular characterization of the murine herpesvirus 68 genome. J. Gen. Virol. 71:1355-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenner, R. G., M. M. Alba, C. Boshoff, and P. Kellam. 2001. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent and lytic gene expression as revealed by DNA arrays. J. Virol. 75:891-902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopes, F. B., S. Colaco, J. S. May, and P. G. Stevenson. 2004. Characterization of the MHV-68 glycoprotein B. J. Virol. 78:13370-13375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez-Guzman, D., T. Rickabaugh, T. T. Wu, H. Brown, S. Cole, M. J. Song, L. Tong, and R. Sun. 2003. Transcription program of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 77:10488-10503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGeoch, D. J. 2001. Molecular evolution of the gamma-Herpesvirinae. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 356:421-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nash, A. A., and N. P. Sunil-Chandra. 1994. Interactions of the murine gammaherpesvirus with the immune system. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 6:560-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Speck, S. H., and H. W. Virgin. 1999. Host and viral genetics of chronic infection: a mouse model of gamma-herpesvirus pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:403-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevenson, P. G., J. S. May, X. G. Smith, S. Marques, H. Adler, U. H. Koszinowski, J. P. Simas, and S. Efstathiou. 2002. K3-mediated evasion of CD8(+) T cells aids amplification of a latent gamma-herpesvirus. Nat. Immunol. 3:733-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevenson, P. G., J. M. Boname, B. de Lima, and S. Efstathiou. 2002. A battle for survival: immune control and immune evasion in murine gamma-herpesvirus-68 infection. Microbes Infect. 4:1177-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Virgin, H. W., P. Latreille, P. Wamsley, K. Hallsworth, K. E. Weck, A. J. Dal Canto, and S. H. Speck. 1997. Complete sequence and genomic analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 71:5894-5904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]