Abstract

HIV disproportionately affects racial/ethnic minorities and individuals living in the southern United States, and missed clinic visits account for much of this disparity. We sought to evaluate: (1) predictors of missed initial HIV medical visits, (2) time to initial visit, and (3) the association between initial visit attendance and retention in HIV care. Chart reviews were conducted for 200 consecutive HIV-infected patients (100 in Dallas, 100 in San Antonio) completing case management (CM) intake. Of these, 52 (26%) missed their initial visit, with 22 (11%) never presenting for care. Mean age was 40 years, 85% were men, >70% were of minority race/ethnicity, and 28% had a new HIV diagnosis. Unemployment (OR [95% CI] = 2.33 [1.04–5.24], p = 0.04) and lower attendance of CM visits (OR = 3.08 [1.43–6.66], p = 0.004) were associated with missing the initial medical visit. A shorter time to visit completion was associated with CD4 ≤ 200 (HR 1.90 [1.25–2.88], p = 0.003), Dallas study site (HR = 1.48 [1.03–2.14], p = 0.04), and recent hospitalization (HR = 2.18 [1.38–3.43], p < 0.001). Patients who did not complete their initial medical visit within 90 days of intake were unlikely to engage in care. Initial medical visit attendance was associated with higher proportion of visits attended (p = 0.04) and fewer gaps in care (p = 0.01). Missed medical visits were common among HIV patients initiating or reinitiating care in Texas. Employment and CM involvement predicted initial medical visit attendance, which was associated with retention in care. New, early engagement strategies are needed to decrease missed visits and reduce HIV health disparities.

Keywords: : HIV, missed visits, linkage to care, retention in care

Introduction

Despite remarkable developments in HIV treatment over the past several decades, the majority of patients with HIV in the United States do not benefit from these advances because they have stalled along the HIV care cascade.1 The largest declines in the HIV care cascade are from diagnosis (86%) to linkage to care (69%) to retention in care (40%).2 Even larger gaps in the HIV care cascade have been identified among racial/ethnic minorities (African Americans, Latinos), younger patients, and those living in the South.1,3 Attending a medical appointment with an HIV provider is a critical step for progression along the HIV care cascade, and missed HIV clinic visits may account for much of the disparity in HIV virologic suppression among minority groups.4,5 In two large safety-net clinics in Dallas and San Antonio, Texas, serving majority African American and Latino populations, respectively, 34–41% of initial HIV medical visits were missed.6

Missed initial medical visits are associated with higher rates of hospitalization and increased mortality for people living with HIV, and represent a significant failure in the quality of care.7–11 Missed visits place the patient at risk for AIDS and death and the public health at risk because the benefits of HIV transmission risk reduction from antiretroviral therapy (ART) are lost.12,13 In addition, when a patient misses an appointment, it results in inefficient utilization of clinic resources by occupying a valuable time slot which could have been used for other patients. Multiple patient, provider, and system-level factors have been associated with poor linkage to and retention in medical care among HIV patients, including illness severity, mental illness, homelessness, patient–provider interactions, long wait for provider appointments, and complex system navigation.14,15

However, given the magnitude of the problem of engagement in HIV care, there are relatively few interventions that show a significant impact on missed visits (either initial or follow-up visits).16–22 and it is unknown which populations benefit most from which strategies. In addition, little is known about the impact of missed initial visits on long-term retention in the care of patients. Giordano et al. found that of 404 patients establishing care after completion of an intake visit, 11% of patients never attended a visit in the 8-month study window, 37% attended a visit but then had a 6-month or greater gap in care, and 53% established and remained in care. Injection drug use, current alcohol, and former drug use were associated with difficulty establishing care, whereas older age was protective; however, this study did not examine retention beyond the 8-month study window.23 Similarly, although it did not examine missed visits, a study by Ulett et al. among individuals who had linked to care, found that 2-year retention in HIV care was worse in those with high CD4 counts and substance use and better among older patients and those with an affective mental illness.24 More data are needed to understand the association between attendance of initial medical visits, timing of linkage to HIV care, and subsequent retention in care.

Given the ongoing high rates of missed initial medical visits, their role in health disparities, and uncertainty about which existing or new strategies will be most effective in reducing missed visits, we sought to examine this issue in more detail in two large Southern HIV clinics that predominantly serve racial and ethnic minorities. In this study, we sought to (1) determine predictors of missed initial HIV medical visits, (2) determine predictors of time to attendance of any HIV medical visit, and (3) define the association between initial HIV medical visit attendance and subsequent retention in care.

Methods

A retrospective detailed chart review was performed at two separate clinics—Amelia Court HIV Clinic (part of Parkland Health and Hospital System) in Dallas, Texas and the Family-Focused AIDS Clinical Treatment Services (FFACTS) Clinic (part of the University Health System) in San Antonio, Texas. Data were collected through electronic medical record and case management (CM) record review. This project was determined to be exempt by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Electronic medical record data were reviewed for 200 consecutive HIV-infected patients (100 in Dallas, 100 in San Antonio) who were scheduled for a new patient medical visit after January 1, 2014. Individuals ≥18 years of age, with confirmed HIV infection, and who had completed CM intake were included. Patients are scheduled for new patient medical visits if they are newly diagnosed with HIV and this is their initial medical visit, if they have been out of care for over 12 months and are returning to care, or if they are transferring their HIV care from an outside facility. All patients must complete a CM intake appointment before being assigned a medical visit. This intake appointment occurs on site at the medical clinic and involves confirming eligibilty to receive services (photo ID, proof of residence, etc.) and completing a needs assessment (housing, dental, substance use, mental health, transportation, financial support, and care coordination) with referrals to appropriate services. Individuals may be scheduled for additional CM appointments (on site in the HIV clinic) after intake based on identified needs. Retention in care data were collected 1 year after the initial data collection, with the study period ending April 5, 2016. The sources from which data were abstracted were Epic (Epic, Verona, WI) and CM records in Dallas and from Allscripts® Sunrise™ Enterprise Release 15.3 (Allscripts, Chicago, IL), AIDS Regional Information and Evaluation System (ARIES), a collaborative program with the States of Texas and California, and Centricity® Framework IDXWeb (powered by General Electric Company) in San Antonio.

The following variables were collected for all subjects: demographic variables (age, race, ethnicity, HIV risk factor, insurance coverage, highest education, housing, employment, income, primary language, and country of origin), type of referral for intake (new diagnosis, out of care, or transitioning from an outside facility), appointment details (time of month, day of week, time of day scheduled, and time interval between intake and medical appointment), attendance of CM appointments (dichotomized into high vs. low attendance based on median for each site), clinical status (CD4, viral load, on ART), years living with HIV, and number of emergency department visits and hospitalizations in preceding 6 months. In addition, data on comorbidities were abstracted from CM intake assessment forms, which incorporated internal and external records if available at the time of intake. These included substance use (self-reported current or former crack/cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, prescription opiates, or alcohol use), mental health diagnoses (depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder based on ICD-9/10 codes and problem list), and additional needs identified during the needs assessment component of CM intake (housing, transportation, financial, social support, and adherence counseling).

The primary outcome was dichotomous attendance status at the initial scheduled medical visit: missed versus attended. Time to first medical visit was the secondary outcome, which was defined as the interval between the completion of CM intake and the first attended medical visit within the study period. If the initial scheduled visit was rescheduled to a different date (e.g., an earlier date for illness severity), then the rescheduled date was counted as the first medical visit. If the initial scheduled visit was missed, but a follow-up scheduled visit was attended, the time to first medical visit was computed using the date of this attended visit. Individuals were censored at the date of attended provider visit, the end of observation period or death, whichever occurred first.

For the retention in care analyses, a second phase chart review was completed 1 year later in the same study population to collect the number of medical visits scheduled and attended in the interim. Retention in care was examined among those who were not known to have transferred their HIV care to a different clinic (n = 155) using the following methods as (1) having at least one visit in each 6-month interval, with visits at least >60 days apart [Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) metric], (2) no visit in the past 6 months (gap in care), (3) count of missed visits, and (4) proportion of all scheduled visits that were missed.

Statistical analyses

Variables were combined from both sites for data analyses. Baseline characteristics were summarized using appropriate descriptive statistics and were compared between the patients who did and did not attend their initial scheduled medical visit using Fischer exact for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Multiple logistic regression was performed to determine predictors of missing the initial scheduled medical visit. A backward elimination model was used and the predictors remained in the final model were those who either had a p value of <0.1 or had a significant univariate/unadjusted association with the outcome of interest (i.e., p < 0.05).

Time to first medical visit attendance was first examined using Kaplan–Meier curve for all patients. Cox proportional hazards model was used to evaluate the impact of potential confounding variables on time to first medical visit. Predictors included in the Cox model were determined by clinical judgment and data availability. For retention in care, summary statistics were used to describe the outcome measures of interest among subjects who attended the initial scheduled medical provider visit versus those who did not. The differences between these two groups were examined using Fisher's exact test for categorical measures and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous measures. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of 200 patients scheduled for an initial medical visit, 52 (26%) missed the scheduled visit, with 22 (11%) never presenting for care during the study period. Overall, mean age was 40 years, 85% were men, over 70% were of minority race/ethnicity (35% black, 37% Hispanic), 29% white. More than half were men who have sex with men (MSM, 61%), unemployed (51%), and receiving charity care (including Ryan White funding and county subsidies) (63%). New HIV diagnoses represented 28%; 46% were returning to care after >12 months and 26% were transferring into clinic. In addition, 39% had a mental health diagnosis, 48% reported current substance use (including alcohol), and 27% had a CD4 < 200 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Individuals Who Attended Versus Missed the Initial HIV Medical Provider Visit

| Characteristic | Attended (N = 148) | Missed (N = 52) | All subjects (N = 200) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, n (%) | 0.17a | |||

| 18–24 | 11 (7.4) | 8 (15.4) | 19 (9.5) | |

| 25–49 | 100 (67.6) | 35 (67.3) | 135 (67.5) | |

| 50+ | 37 (25) | 9 (17.3) | 46 (23) | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.04a | |||

| Women | 26 (17.6) | 3 (5.8) | 29 (14.5) | |

| Men | 122 (82.4) | 49 (94.2) | 171 (85.5) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | 0.009a | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 42 (29) | 14 (27.5) | 56 (28.6) | |

| Hispanic | 45 (31) | 27 (52.9) | 72 (36.7) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 58 (40) | 10 (19.6) | 68 (34.7) | |

| HIV risk factor, n (%) | 0.28a | |||

| IDU | 10 (8.9) | 4 (7.8) | 14 (7.2) | |

| MSM/IDU | 10 (8.9) | 2 (3.9) | 12 (6.2) | |

| MSM | 75 (52.1) | 34 (66.7) | 109 (55.9) | |

| Heterosexual | 49 (34) | 11 (21.6) | 60 (30.8) | |

| Referral type, n (%) | 0.98a | |||

| New diagnosis | 40 (27) | 15 (28.8) | 55 (27.5) | |

| New to clinic | 40 (27) | 13 (25) | 53 (26.5) | |

| Out of care | 68 (45.9) | 24 (46.2) | 92 (46) | |

| Years living with HIV (median [Q1, Q3]) | 7.5 [2, 13] | 7 [2, 11.5] | 7 [2, 13] | 0.34b |

| Primary language, n (%) | 1a | |||

| English | 133 (89.9) | 47 (90.4) | 180 (90) | |

| Spanish/other | 15 (10.1) | 5 (9.6) | 20 (10) | |

| Highest education, n (%) | 0.76a | |||

| <HS | 33 (22.6) | 10 (19.2) | 43 (21.7) | |

| HS/GED | 53 (36.3) | 23 (44.2) | 76 (38.4) | |

| Associates degree | 37 (25.3) | 13 (25) | 50 (25.3) | |

| College degree | 23 (15.8) | 6 (11.5) | 29 (14.6) | |

| Employment, n (%) | 0.09a | |||

| Employed | 55 (37.4) | 19 (37.3) | 74 (37.4) | |

| Unemployed | 70 (47.6) | 30 (58.8) | 100 (50.5) | |

| Disabled | 22 (15) | 2 (3.9) | 24 (12.1) | |

| Monthly household income (median, [Q1, Q3]) | 721 [0, 1300] | 721 [0, 1212] | 721 [0, 1299] | 0.88b |

| Primary insurance, n (%) | 0.94a | |||

| Private | 17 (11.5) | 7 (13.7) | 24 (12.1) | |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 37 (25) | 12 (23.5) | 49 (24.6) | |

| Charity care | 94 (63.5) | 32 (62.7) | 126 (63.3) | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Site, n (%) | <0.001a | |||

| San Antonio | 63 (42.6) | 37 (71.2) | 100 (50) | |

| Dallas | 85 (57.4) | 15 (28.8) | 100 (50) | |

| On ART at intake, n (%) | 63 (42.6) | 15 (28.8) | 78 (39) | 0.1a |

| CD4 count at intake ±180 days, n (%) | 0.3a | |||

| ≤200 | 41 (29.5) | 6 (16.7) | 47 (26.9) | |

| 201–499 | 50 (36) | 16 (44.4) | 66 (37.7) | |

| ≥500 | 48 (34.5) | 14 (38.9) | 62 (35.4) | |

| Viral load at intake, n (%) | N = 103 | N = 20 | N = 123 | 0.42a |

| Undetectable | 30 (29.1) | 7 (35) | 37 (30.1) | |

| 21–10,000 | 21 (20.4) | 1 (5) | 22 (17.9) | |

| 10,001–100,000 | 26 (25.2) | 6 (30) | 32 (26) | |

| >100,000 | 26 (25.2) | 6 (30) | 32 (26) | |

| ED visits 6 months before intake, n (%) | 0.84a | |||

| 0 | 117 (80.1) | 43 (82.7) | 160 (80.8) | |

| 1+ | 29 (19.9) | 9 (17.3) | 38 (19.2) | |

| Hospitalizations 6 months before intake, n (%) | 0.04a | |||

| 0 | 120 (82.2) | 49 (94.2) | 169 (85.4) | |

| 1–2 | 26 (17.8) | 3 (5.8) | 29 (14.6) | |

| CM visit attendance, n (%) | 0.02a | |||

| Low | 43 (29.1) | 25 (48.1) | 68 (34) | |

| High | 105 (70.9) | 27 (51.9) | 132 (66) | |

| Comorbidities/additional needs | ||||

| Substance abuse, n (%) | 0.62a | |||

| Current | 74 (50) | 22 (42.3) | 96 (48) | |

| Former | 19 (12.8) | 7 (13.5) | 26 (13) | |

| None | 55 (37.2) | 23 (44.2) | 78 (39) | |

| Mental health diagnosis, n (%) | 59 (41.3) | 16 (32) | 75 (38.9) | 0.31a |

| Additional needs, n (%) | ||||

| Transportation | 23 (15.5) | 7 (13.5) | 30 (15) | 0.82a |

| Income/funding | 45 (30.4) | 9 (17.3) | 54 (27) | 0.07a |

| Social support | 15 (10.1) | 5 (9.6) | 20 (10) | 1a |

| Adherence | 22 (14.9) | 3 (5.8) | 25 (12.5) | 0.14a |

| Mental health | 28 (18.9) | 12 (23.1) | 40 (20) | 0.55a |

| Other medical condition | 44 (29.7) | 9 (17.3) | 53 (26.5) | 0.1a |

| Substance abuse | 14 (9.5) | 6 (11.5) | 20 (10) | 0.79a |

p value Fisher Exact test.

p value Mann–Whitney U test.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; CM, case management; ED, emergency department; GED, general education development; HS, high school; IDU, injection drug use.

Predictors of missed initial scheduled medical visit

Without adjustment, patients who missed the initial scheduled visit were more likely to be Hispanic, from the San Antonio site, have no hospitalization 6 months before the intake, and have low CM visit attendance (Table 1). After adjustment, unemployment (OR [95% CI] = 2.33 [1.04–5.24] vs. employed, p = 0.04), lower attendance of CM visits (OR = 3.08 [1.43–6.66], p = 0.004), and younger age (OR = 0.96 [0.93–0.996], p = 0.03) were significantly associated with missing the initial scheduled medical visit (Table 2). Missing the initial scheduled medical visit was not associated with the care status of the patient (new diagnosis vs. returning to care), mental health diagnoses, or substance use.

Table 2.

Predictors of Missed Initial Scheduled HIV Medical Visit

| Variable | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| >7 days to provider visit | 6.92 (0.81–58.99) | 0.08 |

| Age, years | 0.96 (0.93–0.996) | 0.03 |

| Male gender | 3.30 (0.82–13.26) | 0.09 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | Ref | — |

| Hispanic | 1.44 (0.59–3.53) | 0.43 |

| Black | 0.57 (0.19–1.65) | 0.30 |

| Employment | ||

| Employed | Ref | — |

| Disabled | 0.77 (0.14–4.22) | 0.76 |

| Unemployed | 2.33 (1.04–5.24) | 0.04 |

| Dallas site | 0.52 (0.22–1.24) | 0.14 |

| Fewer CM visits | 3.08 (1.43–6.66) | 0.004 |

| Hospitalized 6 months before intake | 0.49 (0.12–1.95) | 0.31 |

CM, case management.

Time to complete the initial medical visit

Fifty percent of the patients had their first medical visit at 36 days after the CM intake [95% CI 32–41]. After adjusting for age, gender, race/ethnicity, employment status, and CM visit attendance, a shorter time to completing a medical visit was significantly associated with Dallas study site (HR = 1.48 [1.03–2.14], p = 0.04), recent hospitalization (HR = 2.18 [1.38–3.43], p ≤ 0.001), and low CD4 count (HR = 1.9 [1.25–2.88] ≤200 vs. ≥500, p = 0.003) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Predictors of Time to First Medical Visit

| Variable | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 | 0.07 |

| Female gender | 1.26 | 0.79–2.02 | 0.33 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | Ref | — | |

| Hispanic | 1.09 | 0.71–1.66 | 0.71 |

| Black | 1.31 | 0.86–2.02 | 0.21 |

| Employment | |||

| Unemployed | Ref | — | |

| Employed | 1.30 | 0.91–1.86 | 0.15 |

| Disabled | 1.59 | 0.94–2.68 | 0.08 |

| Dallas site | 1.48 | 1.03–2.14 | 0.04 |

| High CM visit frequency | 1.03 | 0.71–1.49 | 0.88 |

| Hospitalization in past 6 months | 2.18 | 1.38–3.43 | <0.001 |

| CD4 count | |||

| ≥500 | Ref | — | |

| 201–499 | 1.14 | 0.76, 1.70 | 0.53 |

| ≤200 | 1.90 | 1.25, 2.88 | 0.003 |

CM, case management.

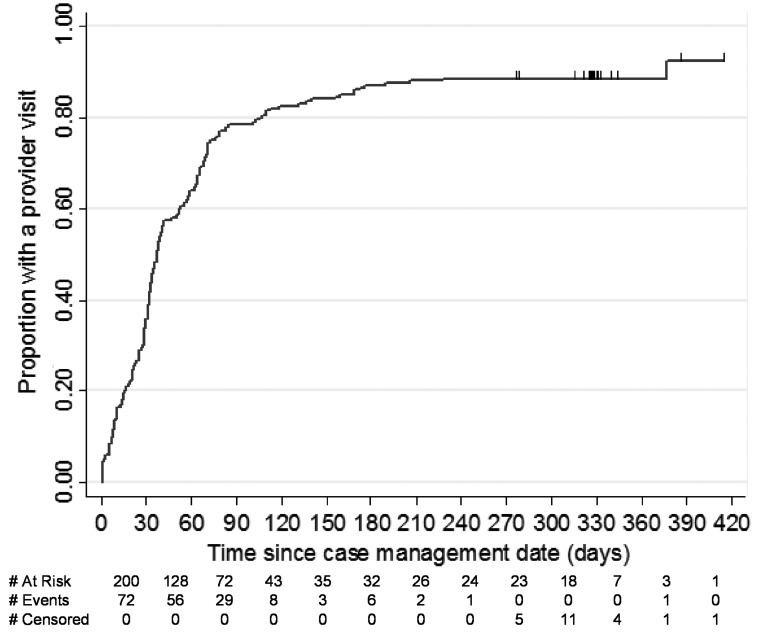

In this cohort, patients who failed to complete their initial medical visit within 90 days of intake were unlikely to engage in care (Fig. 1). Overall, 157/200 (78.5%) presented for care within 90 days. An additional 21 individuals (10.5%) completed an initial medical visit after 90 days. Of the 22 who never had a clinic visit in the study period, 12 were later determined to have transferred their care. No individuals were censored due to death of the 11 patients who died in this study cohort, 10 attended a medical visit before death, and one died after the observation period.

FIG. 1.

Proportion of patients attending initial HIV medical provider visit by time since case management intake visit.

Retention in care

Among patients who were not known to have transferred their HIV care to a different clinic (n = 155), those who attended their initial medical visit were more likely to be retained in care (by HRSA metric, 40% vs. 14%, p < 0.01) than those who missed their initial visit. They were less likely to have a gap in care (10% vs. 28% had no visit in the past 6 months, p = 0.01) and had a lower proportion of scheduled visits that were missed (median 33% vs. 50% missed, p = 0.04). Both groups had a similar number of absolute missed visits (median 1 vs. 1.5, p = 0.71) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Healthcare Utilization and Retention in HIV Care Among Individuals Who Attended Versus Those Who Missed the Initial Scheduled Medical Provider Visit

| Variable | Attended provider visit (N = 119), n (%) | Missed provider visit (N = 36), n (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number ED visits, n (%) | 0.51a | ||

| 0 | 72 (61) | 24 (67) | |

| 1 | 18 (15) | 7 (19) | |

| 2 | 12 (10) | 1 (3) | |

| 3 | 8 (7) | 1 (3) | |

| 4 | 2 (2) | 1 (3) | |

| 8 | 3 (3) | 1 (3) | |

| ED visits, n (%) | |||

| Any | 47 (40) | 12 (33) | 0.56a |

| Hospitalizations, n (%) | |||

| Any | 29 (24) | 8 (22) | 1a |

| Death | 9 (8) | 2 (6) | 1a |

| Total number of visits scheduled, median [Q1, Q3] | 5 [4, 8] | 5 [2, 7] | 0.04b |

| Total number of visits attended, median [Q1, Q3] | 4 [2, 5] | 2 [1, 4] | <0.01b |

| Total number of visits missed, median [Q1, Q3] | 1[1, 3] | 1.5 [1, 3.5] | 0.71 |

| HRSA retention, n (%) (visit every 6 months with 60 days in between visits) | 48 (40) | 5 (14) | <0.01a |

| Gap in care, n (%) (no visit in past 6 months) | 12 (10) | 10 (28) | 0.01a |

| Percentage of scheduled visits missedc, median [Q1, Q3] | 33.3 [12.5, 50] | 50 [25, 66.7] | 0.04b |

p value Fisher Exact test.

p value Mann–Whitney test.

Seven had either missed IMV and/or 0 visits scheduled after IMV.

ED, emergency department; HRSA, Health Resources and Services Administration; IMV, initial medical visit.

Discussion

Missed initial medical visits were common among HIV patients initiating or reinitiating care in outpatient clinics in Dallas and San Antonio, Texas. Employment and engagement in CM predicted attendance of the initial medical visit. There was a trend toward improved attendance of medical visits that were scheduled within 7 days of completion of the CM appointment, but this did not reach statistical significance. Longer time to engage in care was seen in younger patients, those with a CD4 > 200, who had not been recently hospitalized or who were accessing care in San Antonio.

In addition, patients who failed to engage in medical care within 90 days were at high risk for nonengagement. Conversely, patients who attended their initial medical visit attended more visits overall and were more likely to have sustained retention in care. However, both groups (those who attended and those who missed their initial medical visit) had high rates (35–47%) of missing scheduled follow-up visits during the study period.

There are several important implications of this study. Unemployment and low engagement in CM were associated with missed visits. Other studies have found that employment predicts positive HIV-related outcomes25,26 and employment could facilitate clinic visit attendance through access to transportation, or as a marker of education, organizational skills, and self-efficacy, as well as fewer medical comorbidities. However, limited data exist on interventions for improving employment for individuals living with HIV and its potential impact on outcomes.27 Unemployment is interconnected with other social determinants of health, including poverty, education, and insurance, and it is likely that the larger socioeconomic context contributes to ongoing health disparities in HIV outcomes.28 Due to these social support needs, engagement in CM has been shown to improve linkage to care for newly diagnosed HIV patients16 and CM continues to be a critical component of comprehensive HIV care. Interestingly, substance use and mental illness were not associated with missing the initial medical visit, despite their high prevalence in this cohort and an established association between these factors and poor engagement in HIV care.29,30 This may be due to combining multiple types of substances (including alcohol) and various types of mental illness into summary variables and thereby potentially obscuring associations between certain specific variables (e.g., crack cocaine use, depression) with visit attendance.

Time to engage in care has been monitored with more intensity over recent years by researchers, HIV clinics, and health departments, as this interval may predict long-term outcomes, including retention in care and virologic suppression.31 In our study, longer time to appointment was seen in patients who had higher CD4 counts and were not recently hospitalized, which is likely due to the Dallas Clinic Policy of expediting appointments for patients with AIDS and both sites' focus on rapid follow-up for those who were recently discharged from the hospital. The finding that younger patients take longer to engage in care is consistent with national data, although some studies report that younger individuals have similar timing of linkage to HIV care, but poorer retention in HIV care than their older counterparts.32–35 Additional factors associated with delayed linkage to care have been described in other quantitative and qualitative studies, including recent release from incarceration,36 required HIV testing,37 latino ethnicity,38 lack of trust in physicians,39 fear, psychological distress, and lack of information.40

Recent domestic and international studies have evaluated rapid linkage to care, including same-day initiation of ART after HIV has been diagnosed, which has been shown to improve ART uptake, result in a more rapid decline in HIV viral load, and increase virologic suppression rates.41,42 Other innovative approaches to encouraging linkage to and retention in care include mobile health text messaging43 and youth-friendly structures of care.44 Expedited linkage to care may decrease the number of separate times an individual needs to visit the clinic, laboratory and pharmacy, and it's possible that this sense of urgency and focus on the patient may reinforce not only the importance of engagement in HIV care and ART, but also that the individual and his/her health are valued. The updated National HIV/AIDS Strategy reflects this change toward accelerated engagement in care, defining linkage to care goals for 2020 as within 30 days of HIV diagnosis.45

Not only is early engagement in care beneficial, but also delayed linkage to care is associated with poor retention.46 The traditional definition of linkage to care is attending a medical visit within 90 days of being diagnosed with HIV, and we found that after this critical time window of 90 days after CM intake, patients were unlikely to engage in care at all (only 11% attended the initial visit after 90 days). However, many in our cohort were reengaging in care rather than linking to care for the first time, and most “lost to care” initiatives typically require 6 months or more without any clinical visits for an individual to be considered “out of care” and eligible for outreach efforts.47 Our data suggest that waiting until 6 months is not necessary and that efforts to contact and locate those who have missed visits should be implemented sooner. Although some patients (23%) were later determined to have transferred their HIV care elsewhere, collaboration with regional health departments, such as in recent “data to care” initiatives (where surveillance data are used to identify out-of-care HIV-infected individuals)47 could help with real-time identification of those not engaged in HIV care elsewhere and more efficiently focus outreach efforts.

Lastly, we found that attending the initial medical visit (regardless of timing) was associated with fewer gaps in care, a lower proportion of scheduled visits that were missed and better retention in HIV care. It is possible that those attending their initial visit were more motivated to access HIV treatment and, therefore, more adherent to appointments. However, it is also possible that those attending the initial visit started medical treatment sooner, avoiding HIV-related and other health complications, and were able to access other needed services—social support, mental health, housing, dental—and that these services facilitated ongoing engagement in care. To truly improve and sustain the steps of the HIV care cascade, future interventions will need to simultaneously focus on linkage to and retention in care. Specifically, a missed initial medical visit should trigger early outreach interventions from the clinic and regardless of initial visit attendance, retention in care efforts should continue into the first year of (re)engagement in HIV care.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small, although detailed chart reviews were performed on all 200 individuals and the study cohort is representative of two diverse clinics. Second, this study is observational and retrospective; however, it does reflect real-world clinical practices and provides relevant data to inform future interventions in similar HIV clinic settings. Lastly, these data, although detailed, are strictly quantitative and therefore do not provide information about the “why” of missed clinic visits, including patient and provider perspectives. However, this project is a part of a mixed methods study, and forthcoming qualitative data from these two clinics will help inform future patient-centered interventions.

In sum, we have found that missed initial medical visits at two large safety-net HIV clinics in the South were common, were more frequent among the unemployed and those attending fewer CM visits, and were associated with poor retention in care. The Southern United States is the current epicenter of the US HIV epidemic, and findings from these two large, public hospitals serving majority–minority populations may have implications for engagement in care throughout the region. We found that certain groups (younger, healthier individuals) were likely to have delayed engagement in care and that if individuals did not attend a medical visit within 3 months, they were very unlikely to engage in care at all. Although it has been demonstrated that missed HIV clinic visits are as strong a predictor of mortality as having a low CD4+ cell count,9 a missed clinic visit is not typically treated with the same clinical importance and urgency as a patient who has a CD4+ cell count less than 200 cells/μL. A potential implication of our study is that more rapid linkage to and reengagement in HIV care, and a more urgent and coordinated response to missed visits with increased CM attention, may result in better attendance of initial medical visits, which may in turn improve retention in care and long-term clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge research funding from the University of Texas Patient Safety and Research Award (A.E.N., B.S.T.) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [K23 AI112477 (A.E.N.) and K23 AI081538 (B.S.T.)].

Author Disclosure Statement

A.E.N. receives research funding from Gilead Sciences.

References

- 1.Bradley H, Hall HI, Wolitski RJ, et al. . Vital signs: HIV diagnosis, care, and treatment among persons living with HIV—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:1113–1117 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen SM, Van Handel MM, Branson BM, et al. . Vital signs: HIV prevention through care and treatment—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:1618–1623 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reif SS, Whetten K, Wilson ER, et al. . HIV/AIDS in the Southern USA: A disproportionate epidemic. AIDS Care 2014;26:351–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zinski A, Westfall AO, Gardner LI, et al. . The contribution of missed clinic visits to disparities in HIV viral load outcomes. Am J Public Health 2015;105:2068–2075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Allison JJ, et al. . Racial disparities in HIV virologic failure: Do missed visits matter? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;50:100–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nijhawan ALY, Vysyaraju K, Muñoz J, et al. . Predictors of Missed Initial Medical Visits in Two Urban HIV Clinics in the South. Paper presented at Academy Health, Boston, MA, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horberg MA, Hurley LB, Silverberg MJ, et al. . Missed office visits and risk of mortality among HIV-infected subjects in a large healthcare system in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:442–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, Moore RD, et al. . Establishment, retention, and loss to follow-up in outpatient HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;60:249–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Willig JH, et al. . Missed visits and mortality among patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment. Clin Infect Dis 2009;48:248–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiwuwa-Muyingo S, Oja H, Walker AS, et al. . Dynamic logistic regression model and population attributable fraction to investigate the association between adherence, missed visits and mortality: A study of HIV-infected adults surviving the first year of ART. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walburn A, Swindells S, Fisher C, et al. . Missed visits and decline in CD4 cell count among HIV-infected patients: A mixed method study. Int J Infect Dis 2012;16:e779–e785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Westfall AO, et al. . Early retention in HIV care and viral load suppression: Implications for a test and treat approach to HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;59:86–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. . Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:493–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauman LJ, Braunstein S, Calderon Y, et al. . Barriers and facilitators of linkage to HIV primary care in New York City. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;64 Suppl 1:S20–S26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toth M, Messer LC, Quinlivan EB. Barriers to HIV care for women of color living in the Southeastern US are associated with physical symptoms, social environment, and self-determination. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:613–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, et al. . Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS 2005;19:423–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wohl DA, Scheyett A, Golin CE, et al. . Intensive case management before and after prison release is no more effective than comprehensive pre-release discharge planning in linking HIV-infected prisoners to care: A randomized trial. AIDS Behav 2011;15:356–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner LI, Marks G, Craw JA, et al. . A low-effort, clinic-wide intervention improves attendance for HIV primary care. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55:1124–1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner LI, Giordano TP, Marks G, et al. . Enhanced personal contact with HIV patients improves retention in primary care: A randomized trial in 6 US HIV clinics. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:725–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naar-King S, Outlaw A, Green-Jones M, et al. . Motivational interviewing by peer outreach workers: A pilot randomized clinical trial to retain adolescents and young adults in HIV care. AIDS Care 2009;21:868–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mugavero MJ. Improving engagement in HIV care: What can we do? Top HIV Med 2008;16:156–161 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perron NJ, Dao MD, Kossovsky MP, et al. . Reduction of missed appointments at an urban primary care clinic: A randomised controlled study. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giordano TP, Visnegarwala F, White AC Jr, et al. . Patients referred to an urban HIV clinic frequently fail to establish care: Factors predicting failure. AIDS Care 2005;17:773–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ulett KB, Willig JH, Lin HY, et al. . The therapeutic implications of timely linkage and early retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2009;23:41–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalichman SC, Washington C, Grebler T, et al. . Medication adherence and health outcomes of people living with HIV who are food insecure and prescribed antiretrovirals that should be taken with food. Infect Dis Ther 2015;4:79–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shacham E, Nurutdinova D, Onen N, et al. . The interplay of sociodemographic factors on virologic suppression among a U.S. outpatient HIV clinic population. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2010;24:229–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson R, Okpo E, Mngoma N. Interventions for improving employment outcomes for workers with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;5:CD010090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beer L, Mattson CL, Bradley H, et al. . Understanding cross-sectional racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in antiretroviral use and viral suppression among HIV patients in the United States. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, et al. . Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet 2010;376:367–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, et al. . Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: A review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011;58:181–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Philbin MM, Tanner AE, DuVal A, et al. . Factors affecting linkage to care and engagement in care for newly diagnosed HIV-positive adolescents within fifteen adolescent medicine clinics in the United States. AIDS Behav 2014;18:1501–1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsu LC, Chen M, Kali J, et al. . Assessing receipt of medical care and disparity among persons with HIV/AIDS in San Francisco, 2006–2007. AIDS Care 2011;23:383–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horberg MA, Hurley LB, Klein DB, et al. . The HIV care cascade measured over time and by age, sex, and race in a large national integrated care system. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2015;29:582–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rana AI, Liu T, Gillani FS, et al. . Multiple gaps in care common among newly diagnosed HIV patients. AIDS Care 2015;27:679–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.(CDC) CfDCaP. Key Graphics from CDC Analysis Showing Proportion of People Engaged in Each of the Five Main Stages of HIV Care. 2012. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2012/continuum-of-care-graphics.html (Last accessed December6, 2016)

- 36.Montague BT, Rosen DL, Sammartino C, et al. . Systematic assessment of linkage to care for persons with HIV released from corrections facilities using existing datasets. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2016;30:84–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robertson M, Wei SC, Beer L, et al. . Delayed entry into HIV medical care in a nationally representative sample of HIV-infected adults receiving medical care in the USA. AIDS Care 2016;28:325–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dennis AM, Napravnik S, Sena AC, et al. . Late entry to HIV care among Latinos compared with non-Latinos in a southeastern US cohort. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53:480–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graham JL, Shahani L, Grimes RM, et al. . The influence of trust in physicians and trust in the healthcare system on linkage, retention, and adherence to HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2015;29:661–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sprague C, Simon SE. Understanding HIV care delays in the US South and the role of the social-level in HIV care engagement/retention: A qualitative study. Int J Equity Health 2014;13:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pilcher CD, Ospina-Norvell C, Dasgupta A, et al. . The effect of same-day observed initiation of antiretroviral therapy on HIV viral load and treatment outcomes in a US Public Health setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;74:44–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosen S, Fox MP, Larson BA, et al. . Accelerating the uptake and timing of antiretroviral therapy initiation in sub-Saharan Africa: An operations research agenda. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rana AI, van den Berg JJ, Lamy E, et al. . Using a mobile health intervention to support HIV treatment adherence and retention among patients at risk for disengaging with care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2016;30:178–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee L, Yehia BR, Gaur AH, et al. . The impact of youth-friendly structures of care on retention among HIV-infected youth. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2016;30:170–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White House Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States: Updated To 2020. 2015. Available at: www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/national_hiv_aids_strategy_update_2020.pdf (Last accessed January25, 2016)

- 46.Tripathi A, Youmans E, Gibson JJ, et al. . The impact of retention in early HIV medical care on viro-immunological parameters and survival: A statewide study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2011;27:751–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.(CDC) CfDCaP. Effective Interventions, HIgh Impact Prevention, Data to Care. Health Department Data to Care Program Examples 2015. Available at: https://effectiveinterventions.cdc.gov/en/HighImpactPrevention/PublicHealthStrategies/DatatoCare/HealthDepartmentDatatoCareProgramExamples.aspx (Last accessed December6, 2016)