Abstract

We present a unique case of a symptomatic adverse local tissue reaction in a patient with a ceramic-on-ceramic total hip bearing surface. To our knowledge, this pathological finding has not yet been described in a ceramic-on-ceramic articulation without a cobalt-chromium alloy trunnion or modular neck component as a source of metal wear. We conclude that despite its mechanical mostly benign wear characteristics, ceramic wear debris is not entirely inert and may lead to the development of adverse local tissue reaction.

Keywords: Ceramic-on-ceramic, Pseudotumor, ALTR, Revision total hip arthroplasty, THA

Introduction

Development of adverse local tissue reaction (ALTR) after contemporary total hip arthroplasty (THA) is uncommon outside of cobalt-chromium alloy articulations, but it remains significant complication. The term is used to describe a granulomatous or destructive cystic lesion which develops around a THA, and may have a pathologic appearance of predominantly granulomatous findings if the cause is particulate debris or necrosis [1], inflammatory exudate, and lymphocytes if the etiology is related to metal and/or corrosion debris [2]. The development of ALTR and pseudotumor formation is often related to patient discomfort and pain as the reaction causes not only a soft tissue mass, but also osteolysis, bone erosion, and significant damage to periarticular soft tissues, which can lead to total joint failure and instability.

It is well documented in the orthopaedic literature that ALTR may develop around metal-on-polyethylene implants due to taper corrosion [1], [3], [4] and more commonly, around metal-on-metal (MoM) bearing surfaces in THA [5], [6], [7], [8]. There have been a few case reports of ALTR associated with ceramic-on-polyethylene implants, but they attributed to corrosion at the modular metal neck [9] or from metal debris from the porous coating of the stem [10]. There is no reported case to our knowledge of a pseudotumor related to a ceramic-on-ceramic (CoC) THA. The purpose of this study was to present a unique case of a pseudotumor in a CoC THA.

Case history

In 2005, a 48-year-old woman underwent a left THA for idiopathic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Given the patient's young age, the treating surgeon selected a cementless arthroplasty with a CoC articulation. The patient received a Stryker Trident (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI) titanium acetabular component with a modular 32 mm alumina ceramic liner and 32 mm plus 0 alumina ceramic head. One titanium screw was placed for additional fixation of the cup. The ceramic liner is backed with a titanium alloy that is press fit into the titanium acetabular cup. The femoral component placed was a Stryker Secur-Fit HA (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI) size 6 stem. This is a titanium stem with a hydroxyapatite proximal coating. The patient's post-operative course was unremarkable, and reportedly without infectious complications. Postoperative radiographs showed both components were in acceptable position; however, with a cup abduction of 52°-55° as measured in an anteroposterior pelvis obtained in the supine position.

In January of 2014, then 54 years old, the patient presented for evaluation of a painful total hip. Medical history was significant for peptic ulcer disease, uterine fibroids, and prior episode of viral meningitis due to herpes zoster infection. She denied excessive alcohol use or exposure to steroids. Recent autoimmune workup was negative for any inflammatory conditions. She reported a feeling of “grinding” since implantation, and progressive discomfort and “fullness” since the time of implantation. Current radiographs when compared with immediate postoperative radiographs did not show any evidence of loosening or migration (Fig. 1). Physical examination revealed full extension with flexion of the hip to 110°, with a painful flexion arc beyond 60°. Patient was able to externally rotate to 30°, and internally rotate to 15° at 90° of flexion. A metal artifact reduction protocol magnetic resonance imaging showed a 5.3 × 4.4 × 2.4 cm heterogeneous fluid collection consistent with the appearance of a pseudotumor (Fig. 2). Blood tests showed a white blood cell count of 7.3, a normal differential, and otherwise were within normal limits. Chromium and cobalt levels were obtained, both were found to be normal at 0.2 and 0.2 ppb, respectively. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein were within normal limits. The patient denied constitutional symptoms and the wound showed no erythema, swelling, or drainage. The patient was followed up clinically for 10 months without improvement of her symptoms despite physical therapy and anti-inflammatory medications. After discussion of risks of the procedure, the patient elected to have the CoC articulation revised.

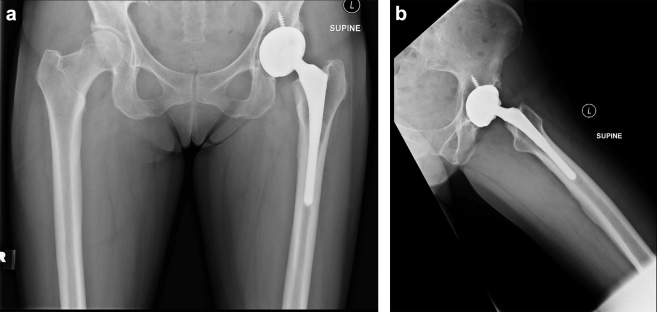

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior (AP) pelvis (a) and frog lateral (b) left hip at presentation showing no evidence of loosening, osteolysis, or apparent complication.

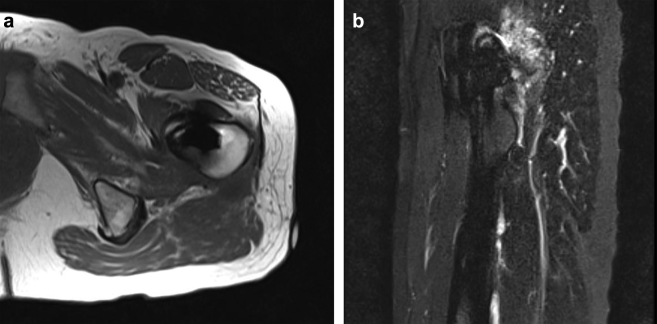

Figure 2.

Axial T2 (a) and sagittal short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequence (b) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing pseudotumor formation with communication with the hip.

A pseudotumor was found measuring 5 × 4 × 3 cm protruding from the joint space just inferior to the repaired piriformis tendon (Fig. 3). It contained caseous appearing material (Fig. 4), which was aspirated and sent for pathology. The stalk of the pseudotumor was then tied off and sent for pathology (Fig. 5). Cultures were obtained at the time of revision, including fungal and acid fast cultures, all of which returned as negative. No abnormal markings or discoloration were present on femoral head before initial dislocation; however, during the dislocation metal transfer from the acetabular cup did occur (Fig. 6). The femoral head was then removed, revealing an intact trunnion without evidence of wear or corrosion. The interior of the ceramic head was also intact without evidence of damage; no metal sleeve had been used in the index procedure. Examination of the neck of the prosthesis and rim of the acetabular shell did not reveal evidence of impingement. No stripe wear was noted on either the head or acetabular component. The ceramic acetabular component was inspected and found to be free from chipping or damage. Although not visibly scratched or marked, it was rough to the touch. No advanced analysis of the components was performed due to lack of availability at the institution. The modular ceramic liner was removed and no wear or corrosion of the metal rim was noted at the time of removal. Testing of the remaining acetabular and femoral components revealed both to be solidly fixed.

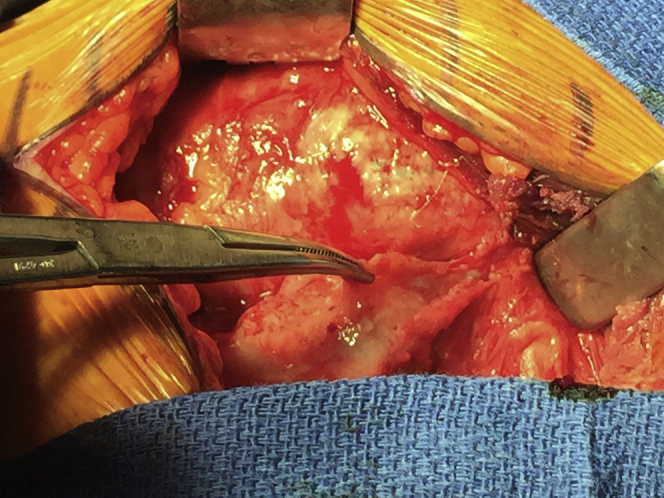

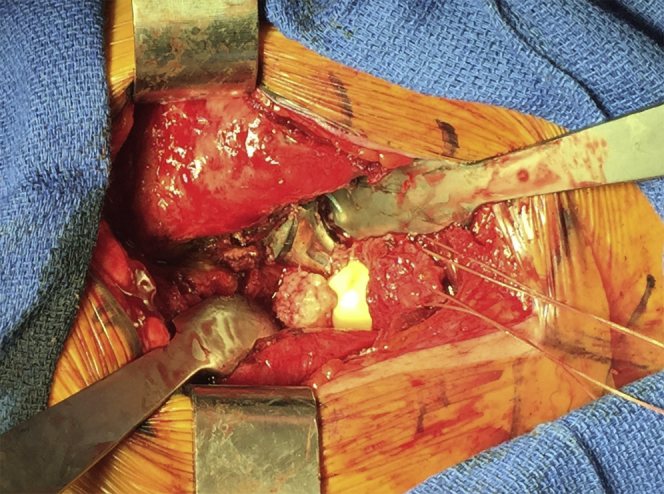

Figure 3.

Intraoperative photograph showing a pseudocyst protruding from the joint capsule, lying on the abductors.

Figure 4.

Intraoperative photograph showing the caseous appearing contents of the cyst in communication with the joint.

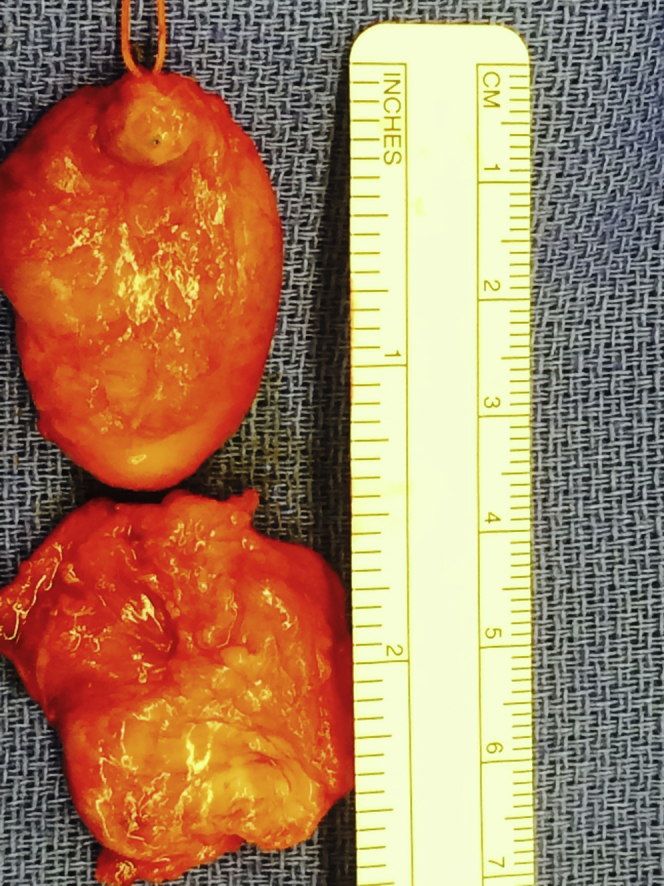

Figure 5.

Photograph of gross specimens removed.

Figure 6.

Photograph of removed ceramic components without obvious defects or stripe wear. The “lead pencil” mark was a result of intraoperative dislocation and not present before dislocation.

After thorough irrigation, a Stryker Trident polyethylene liner (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI) was placed in the acetabular component and a 32-mm chrome cobalt head (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI) was placed on the femoral trunnion. Range of motion testing was performed, and the patient hip was found to be stable.

Pathology was examined on low, intermediate, and high power stained with hematoxylin-eosin to evaluate the pseudotumor and its subsynovial structures that included cytologic, vascular, and cellular components. Low power showed a large, synovial-lined cyst-like structure with flattened to papillary hypertrophic neosynovium with variable regions of synovial layer loss (Fig. 7a-c). High power revealed a subsynovial layer of histiocytes and lymphocytes in a loose, perivascular stroma consistent with mild to moderate long-term inflammation with an occasional eosinophil. Just deep to this histiocytic and/or lymphocytic layer, there were pigmented, laden macrophages juxtaposed to a dense fibrovascular stroma.

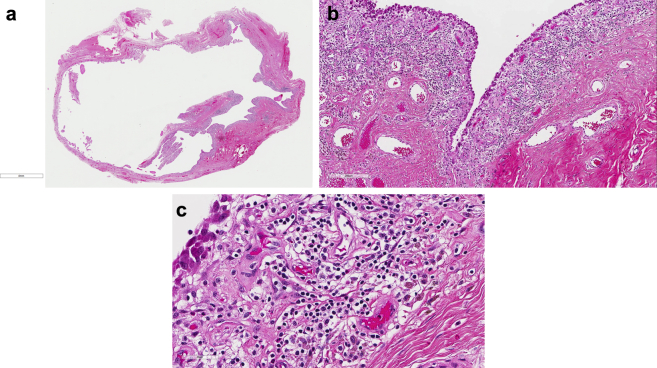

Figure 7.

Low power histology of pseudocyst, displaying synovial lined cyst-like structure (a). Histology of the pseudocyst at 10× (b) and 40× (c) magnification showing the pseudosynovial lined cyst with abundant histiocyte and lymphocyte infiltration.

The patient's postoperative course was unremarkable, and the patient was mobilized with physical therapy on postoperative day 1 and discharged home on postoperative day 4. Patient had no complications and did well with her rehabilitation; she was walking without ambulatory aids by her 8-week follow-up and asymptomatic. She remained free of symptoms at last follow-up 9 months postoperatively and has had no further complications.

Discussion

ALTR and pseudotumor formation, although uncommon in metal-on-polyethylene THA, are well described in MoM bearing surfaces. There is, however, no consensus on the exact cause of the process; and histological appearances vary widely. These processes may represent a delayed type hypersensitivity reaction to the wear products of the MoM articulations [11]. More recently, mechanically assisted crevice corrosion has been implicated as contributing to the formation of ALTR [2], [3]. Other authors theorize that ALTR and pseudotumor formation may be partially related to high wear rates, and not solely to metal sensitivity, and that both may contribute to the clinical condition. In a study of 32 revisions of MoM articulation, Campbell et al found that those patients who had the highest histological scoring of aseptic lymphocyte-dominated vasculitis-associated lesion as described by Doorn et al, had lower wear rate of removed implants, whereas those with the lowest histological aseptic lymphocyte-dominated vasculitis-associated lesion scores showed higher wear rates of removed implants. In addition, those with the higher wear rates showed a greater degree of macrophage response with phagocytized metal debris and a lower degree of lymphocytic response [12].

The formation of pseudotumors and ALTR in MoM articulations was initially quoted to be as low as 1%-4% [8], [11]; however, new data show a prevalence of 36%-61% in well-functioning hips [13], [14]. Pseudotumors are not all symptomatic and not all require immediate treatment; however, their presence is concerning and should be followed closely both clinically and radiographically. Case studies of the natural history of pseudotumor formation as assessed by ultrasound in a cohort of 10 patients showed that only 6 patients had an increase in size at 2-year follow-up. The remaining 4 pseudotumors decreased in size or resolved over the same period [13]. In addition, some authors have found that the incidence of pseudotumor formation to not differ significantly in symptomatic vs asymptomatic MoM hips [14]. Magnetic resonance imaging studies of symptomatic and asymptomatic THA in 174 patients showed that the presence and the size of a pseudotumor did not correlate with pain, but found that the presence of bone marrow edema and tearing of the abductor tendon were associated with pain [15].

Concerns with CoC articulations mostly center around fracture of the ceramic head or liner. Improved manufacturing processes and testing have mitigated some of the risk associated with earlier generation ceramics [16]; however, it remains a significant concern. Although fracture of a ceramic head is an uncommon occurrence, quoted to be as low as 0.01%-0.15% [17], [18], its occurrence sets the stage for massive third body wear after revision, with 5-year survival quoted as low as 63% [19]. In addition, given their low ductility, CoC articulations are less tolerant of component malplacement. This can lead to posterior edge loading and increased wear rates seen in cups placed in too much abduction [18]. Stripe wear, a localized wear crescent of wear on the ceramic head, is another example of wear related to low ductility. It is theorized that there is microseparation of the head from the acetabular cup during the swing phase of gait with return of the head in contact with the rim. This has been shown in multiple retrieval analyses, and may be a cause of concern for long-term wear [18], although this was not present in the above-reported case.

Despite its mostly benign characteristics, ceramic wear debris is not entirely inert. In examination of biopsies of revised CoC articulations, Mochida et al noted a predominantly macrophage response to ceramic debris, which was confirmed with immunohistochemical staining [20]. In vitro studies have shown macrophage injection of ceramic debris will increase proinflammatory cytokine production. In addition, macrophage apoptosis was earlier and more extensive after alumina particle ingestion compared with polyethylene particles of the same size [21]. Ceramic articulations, however, generate several thousand times less wear debris as compared with polyethylene articulations leading to less response [22].

Histologic patterns of ALTR have been well described in previous studies and encompasses a broad range of histologic findings commonly classified by the inflammatory pattern including macrophagic and lymphocytic variability with or without sarcoid-like granulomas. The histology in this case revealed pseudocyst formation with papillary neosynovium with regional synovial layer loss with mixed macrophagic and lymphocytic pattern. This pattern is associated with vascular proliferation that lacked germinal centers, granulomas, or significant plasmacytic and/or eosinophilic features. The histologic findings seen in this case are consistent with the most common patterns described previously in patients with ALTR.

Although pseudotumor formation has been reported in ceramic-on-polyethylene articulations [9], this was in the setting of elevated metal ion levels, and ultimately attributed to modular neck wear. Numerous reports exist of pseudotumor and ALTR reactions in non-MoM articulations in THA, identifying trunnion wear as a source of metal ions [3], [23], [24]. Whitehouse et al reported a similar case of pseudotumor associated with trunnion wear in a hip hemiarthroplasty [25]. Still other case reports exist, proposing exposure and microabradement of porous coating as a source of titanium metal debris as a source of pseudotumor [10].

To the authors' knowledge, this is the first case of such an ALTR pseudotumor seen in a CoC articulation with the absence of a CoCr stem, femoral head, sleeve, or source of Co ions or Co alloy corrosion debris. In addition, there was no obvious trunnion corrosion or particulate debris from impingement. In the absence of any metal articulation, lack of elevated Co or Cr ions, and lack of exposed porous coating, it is reasonable to assume that the ALTR and pseudotumor was in reaction to wear debris from the CoC articulation.

Summary

We present the case of a symptomatic adverse local tissue reaction in a patient with a ceramic-on-ceramic total hip bearing surface. This occurred in the absence of a source of metal debris and without elevation of either chromium or cobalt. The case illustrates that ceramic wear debris is not entirely inert and may lead to the development of adverse local tissue reaction and possible pseudotumor formation.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors of this paper have disclosed potential or pertinent conflicts of interest, which may include receipt of payment, either direct or indirect, institutional support, or association with an entity in the biomedical field which may be perceived to have potential conflict of interest with this work. For full disclosure statements refer to http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.artd.2016.11.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Harris W.H., Schiller A.L., Scholler J.M., Freiberg R.A., Scott R. Extensive localized bone resorption in the femur following total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(5):612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper H.J., Urban R.M., Wixson R.L., Meneghini R.M., Jacobs J.J. Adverse local tissue reaction arising from corrosion at the femoral neck-body junction in a dual-taper stem with a cobalt-chromium modular neck. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(10):865. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGrory B.J., MacKenzie J., Babikian G. A high prevalence of corrosion at the head–neck taper with contemporary Zimmer non-cemented femoral hip components. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(7):1265. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffiths H.J., Burke J., Bonfiglio T.A. Granulomatous pseudotumors in total joint replacement. Skeletal Radiol. 1987;16(2):146. doi: 10.1007/BF00367764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boardman D.R., Middleton F.R., Kavanagh T.G. A benign psoas mass following metal-on-metal resurfacing of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(3):402. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B3.16748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Counsell A., Heasley R., Arumilli B., Paul A. A groin mass caused by metal particle debris after hip resurfacing. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74(6):870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madan S., Jowett R.L., Goodwin M.I. Recurrent intrapelvic cyst complicating metal-on-metal cemented total hip arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120(9):508. doi: 10.1007/s004020000171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pandit H., Glyn-Jones P., McLardy-Smith R. Pseudotumours associated with metal-on-metal hip resurfacings. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(7):847. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B7.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu A.R., Gross C.E., Levine B.R. Pseudotumor from modular neck corrosion after ceramic-on-polyethylene total hip arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2012;41(9):422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McPherson E., Dipane M., Sherif S. Massive pseudotumor in a 28 mm ceramic-polyethylene revision THA: a case report. Reconstr Rev. 2014;4(1):11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon Y.M., Ostlere S.J., McLardy-Smith P. ‘Asymptomatic’ pseudotumors after metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty: prevalence and metal ion study. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(4):511. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell P., Ebramzadeh E., Nelson S. Histological features of pseudotumor-like tissues from metal-on-metal hips. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(9):2321. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1372-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Almousa S.A., Greidanus N.V., Masri B.A., Duncan C.P., Garbuz D.S. The natural history of inflammatory pseudotumors in asymptomatic patients after metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(12):3814. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2944-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart A.J., Satchithananda K., Liddle A.D. Pseudotumors in association with well-functioning metal-on-metal hip prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(4):317. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang E.Y., McAnally J.L., Van Horne J.R. Metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: do symptoms correlate with MR imaging findings? Radiology. 2012;265(3):848. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeffers J.R., Walter W.L. Ceramic-on-ceramic bearings in hip arthroplasty State of the art and the future. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(6):735. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B6.28801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esposito C.I., Walter W.L., Roques A. Wear in alumina-on-alumina ceramic total hip replacements: a retrieval analysis of edge loading. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(7):901. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B7.29115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrack R.L., Burak C., Skinner H.B. Concerns about ceramics in THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;429:73. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000150132.11142.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allain J., Roudot-Thoraval F., Delecrin J. Revision total hip arthroplasty performed after fracture of a ceramic femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(5):825. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200305000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mochida Y., Boehler M., Salzer M., Bauer T.W. Debris from failed ceramic-on-ceramic and ceramic-on-polyethylene hip prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;389:113. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200108000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petit A., Catelas I., Antoniou J., Zukor D.J., Huk O.L. Differential apoptotic response of J774 macrophages to alumina and ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene particles. J Orthop Res. 2002;20(1):9. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bohler M., Mochida Y., Bauer T.W., Plenk H., Jr., Salzer M. Wear debris from two different alumina-on-alumina total hip arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(6):901. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.82b6.9722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao X., Tay G.H., Godbolt D.B., Crawford R.W. Pseudotumor in a well-fixed metal-on-polyethylene uncemented hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(3):493.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bisseling P., Tan T., Lu Z., Campbell P.A., Van Susante J.L.C. The absence of a metal-on-metal bearing does not preclude the formation of a destructive pseudotumor in the hip—a case report. Acta Orthop. 2013;84(4):437. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.823590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitehouse M.R., Endo M., Masri B.A. Adverse local tissue reaction associated with a modular hip hemiarthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(12):4082. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3133-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.