Abstract

Background

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is a clinical syndrome that has been associated with changes in the extracellular matrix. The purpose of this study was to determine whether profibrotic biomarkers accurately reflect the presence and severity of disease and underlying pathophysiology and modify response to therapy in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

Methods and Results

Four biomarkers, soluble form of ST2 (an interleukin-1 receptor family member), galectin-3, matrix metalloproteinase-2, and collagen III N-terminal propeptide were measured in the Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ARB on Management of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (PARAMOUNT) trial at baseline, 12 and 36 weeks after randomization to valsartan or LCZ696. We examined the relationship between baseline biomarkers, demographic and echocardiographic characteristics, change in primary (change in N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide) and secondary (change in left atrial volume) end points. The median (interquartile range) value for soluble form of ST2 (33 [24.6–48.1] ng/mL) and galectin 3 (17.8 [14.1–22.8] ng/mL) were higher, and for matrix metalloproteinase-2 (188 [155.5–230.6] ng/mL) lower, than in previously published referent controls; collagen III N-terminal propeptide (5.6 [4.3–6.9] ng/mL) was similar to referent control values. All 4 biomarkers correlated with severity of disease as indicated by N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide, E/E′, and left atrial volume. Baseline biomarkers did not modify the response to LCZ696 for lowering N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; however, left atrial volume reduction varied by baseline level of soluble form of ST2 and galectin 3; patients with values less than the observed median (<33 ng/mL soluble form of ST2 and <17.8 ng/mL galectin 3) had reduction in left atrial volume, those above median did not. Although LCZ696 reduced N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide, levels of the other 4 biomarkers were not affected over time.

Conclusions

In patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, biomarkers that reflect collagen homeostasis correlated with the presence and severity of disease and underlying pathophysiology, and may modify the structural response to treatment.

Keywords: biomarkers, extracellular matrix, heart failure, homeostasis, pathophysiology

Several novel circulating biomarkers have been used to characterize the molecular and cellular changes that occur during the development of myocardial disease.1–4 In heart failure (HF), these include biomarkers that reflect hemodynamic status (such as natriuretic peptides), inflammation (such as interleukins), and collagen homeostasis (such as collagen peptides and interstitial proteases).2 The profiles of these biomarkers seem to differ significantly in patients with HF with a reduced ejection fraction (EF) versus HF with a preserved EF (HFpEF.5–7 The nature and extent to which biomarkers change in HFpEF as a function of disease severity, degree of left ventricular (LV) structural and functional abnormalities and demographics and comorbid conditions have not been fully defined. In addition, whether baseline biomarkers can modify the response to treatment in HFpEF has not been examined. One potential mechanism hypothesized to play a pivotal role in the development of HFpEF is a change in collagen homeostasis that results in extracellular matrix fibrosis and the development of abnormal diastolic function.8–12 Several molecular and cellular signaling pathways that result in a profibrotic milieu have been identified in previous studies but have not been specifically examined in randomized clinical trials in HFpEF.2,6,7

Patients enrolled in the Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ARB on Management of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction trial (PARAMOUNT) had the clinical syndrome of heart failure and evidence of increased LV filling pressures (symptoms and signs of volume overload and increased N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide [NT-proBNP]).13 We hypothesized that if changes in extracellular matrix fibrillar collagen content lead to abnormal diastolic function, these patients should have changes in biomarkers reflecting this. The purpose of this study was to examine a selected portfolio of postulated profibrotic biomarkers in a defined population of HFpEF, relate these biomarkers to demographic characteristics, changes in LV structure and function, severity of disease and response to treatment. Given the post hoc nature of this analysis and its modest sample size, this study was envisioned as hypothesis generating providing provocative evidence that would lead to additional, larger, and more definitive studies.

Methods

Study Design

PARAMOUNT was a randomized, double-blind, parallel group, active control trial described in detail in previous publications.13 Briefly, men and women aged ≥40 years old with an LVEF ≥45% and a documented history of heart failure with associated signs or symptoms (dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, paroxysmal dyspnea, and peripheral edema) were eligible. Patients were required to have NT-proBNP >400 pg/mL at screening, be on diuretic therapy, and have a systolic blood pressure <140 or ≤160 mm Hg, or less if on ≥3 blood pressure drugs at randomization, have an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of at least 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 at screening, and a potassium concentration of no >5.2 mmol/L. Patients were excluded if they had previous LVEF <45% at any time, isolated right heart failure because of pulmonary disease, dyspnea because of noncardiac causes, such as pulmonary disease, anemia, or severe obesity, primary valvular or myocardial diseases, or coronary artery or cerebrovascular disease needing revascularization within 3 months of screening or likely to need revascularization during the trial. The number of patients enrolled with atrial fibrillation on ECG at screening was limited to roughly 25% of the total. The study protocol was submitted to individual sites’ institutional review boards or ethics committees and all enrolled patients provided written informed consent. A data safety monitoring committee oversaw the program and reviewed trial data for patient safety at regular intervals.

Biomarkers

Plasma and serum were obtained for biomarker determination at baseline, 12, and 36 weeks after randomization. The baseline measurements were made at randomization after a placebo run-in phase. Measurements after randomization to valsartan or LCZ696 were made in 12 and 36 weeks. NT-proBNP and matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) were measured in plasma and collagen III N-terminal propeptide (PIIINP) was measured in serum at Quest Diagnostics (Valencia, CA) using the Elecsys proBNP immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), the Quantikine MMP-2 immunoassay (R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and the UniQ PIIINP radioimmunoassay (Orion Diagnostics, Espoo, Finland). The soluble form of ST-2 (sST-2, an interleukin-1 receptor family member) was measured in serum at Critical Diagnostics (San Diego, CA) using their Presage immunoassay, and Galectin 3 (Gal-3) was measured in serum at Clinical Reference Laboratories (Lenexa, KS) using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (BG Medicine, Waltham, MA).

Echocardiographic Study

Baseline echocardiograms were analyzed in the cardiovascular imaging core laboratory at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA. All measurements were made in triplicate in accordance with the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography.14 LV volumes, mass, relative wall thickness, mitral flow velocities, tissue Doppler velocities, LAV, and LVEF were calculated according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography.14 Left atrial strain and LV global longitudinal strain were measured using vendor-independent 2-dimensional speckle tracking software.15

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were summarized by quartiles of each bio-marker using counts and percentages for binary variables and means and SDs for continuous variables, with the exception of NT-proBNP, which is summarized via median (interquartile range [IQR]) because of skewness. Tests for trend across quartiles were conducted via χ2 trend tests, linear regression, and Cuzick nonparametric trend test, as appropriate. Biomarker data were presented as mean±SEM, geometric mean, and median (IQR) at baseline. Baseline biomarker data were compared with data measured at 12 and 36 weeks after randomization presented as median (IQR) for the entire study group and then divided according to treatment group (valsartan versus LCZ696).

Baseline biomarker data were compared qualitatively with referent control values. Referent control values were presented for comparison as median (IQR). Median (IQR) referent control data for PIIINP and MMP-2 were taken from a previously published study in which 241 subjects of age, sex, and race distribution similar to this study population were examined.5 However, these well-characterized subjects had no clinical, serological, or cardiac structural/functional abnormalities as evidenced by a normal echocardiography and 6-minute hall walk distance. Median (IQR) referent control data for Gal-3 were taken from a previously published study in which 1092 subjects of age, sex, and race distribution similar to this study population were examined.16 Median (IQR) referent control data for sST-2 were aggregated from 3 previously published study (including the Framingham study) in which subjects of age, sex, and race distribution similar to this study population were examined.17–20 Although small differences between men and women have been seen in the biomarkers described above, because the populations of both this study and the referent control populations are roughly 50% female, the referent control values listed in Table 1 represent the total population examined. In addition, biomarker data from this study of patients with HFpEF were compared with previously published groups of patients with HFpEF.5,21–24 Finally, Gal-3 and sST-2 data in this study were compared with Food and Drug Administration approved partition values for risk stratification; these partition values were not specifically designed for risk stratification in HFpEF but were targeted to overall risk in generalized populations.

Table 1.

Biomarker Data

| PARAMOUNT-HF HFpEF Patients

|

Referent Controls

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Geo Mean | Median (IQR) | Median* | |

| sST2, ng/mL | 39.6 (24.7) | 34.7 | 33.0 (24.6–48.1) | 20 (17–26) |

| Galectin-3, ng/mL | 19.0 (6.9) | 17.9 | 17.8 (14.1–22.8) | 12 (9–15) |

| MMP-2, ng/mL | 198 (73) | 184 | 188 (156–231) | 335 (323–443) |

| PIIINP, ng/mL | 6.1 (3.5) | 5.5 | 5.6 (4.3–6.9) | 6.5 (6.1–8.2) |

HFpEF indicates heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; IQR, interquartile range; MMPs, matrix metaloproteinases; PARAMOUNT, Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ARB on Management of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction; PIIINP, collagen III N-terminal propeptide; and sST2, soluble form of ST2 (an Interleukin-1 receptor family member).

Correlations between biomarkers and demographic and echocardiographic data were performed using Spearman correlation. Values for sST-2, Gal-3, and NT-proBNP were log transformed because they were noticeably right skewed. In a multivariable regression model that included age, sex, New York Heart Association class, history of atrial fibrillation, diastolic blood pressure, eGFR, log NT-pro BNP, LV transmitral early diastolic filling velocity/LV early diastolic myocardial velocity (E/E′), and LA volume, we examined which factors were independently associated with baseline levels of biomarkers. Variables included were on the basis of low numbers of missing values and clinical knowledge. To examine the interaction between treatment with LCZ696 and baseline biomarker levels on levels of NT-proBNP at 12 weeks and LA volume at 36 weeks, we used a regression model that included the effect of LCZ696, an interaction term between treatment and baseline biomarker values and stratification variables of region and previous angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor or ARB use as well as baseline NT-proBNP and LA volume, respectively. Where an interaction was found this was explored further by dividing the cohort into values above and below the observed median value of the biomarker and stratified models of the effect of treatment on NT-proBNP and LA volume examined. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 12 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). For interaction tests a P<0.1 was considered suggestive of an interaction, and for all other test a P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and Echocardiographic Data

Data from the 301 randomized patients were included in this study, 149 randomized to LCZ696 and 152 to valsartan. The demographic and echocardiographic data were typical of a stable outpatient HFpEF population29,30; elderly, female, and NYHA class II dominant, receiving multidrug treatment, expected comorbidities, and evidence of abnormal diastolic function with increased NT-proBNP, E/E′, and LA volume. Baseline data are presented for each individual biomarker examined by quartiles (Tables I–IV in the Data Supplement).

Baseline Biomarker Data

In these patients with HFpEF, the baseline median values for Gal-3 and sST-2, summarized in Table 1, were ≈50% higher than the median values from previously published referent control subjects.16–24 In these patients with HFpEF, the median values for MMP-2 were ≈50% lower and PIIINP were similar to previously published referent control subjects.5,31

There were significant correlations between baseline biomarkers and demographic and echocardiographic variables (Table 2). Gal-3, sST-2, and PIIINP increased and MMP-2 decreased in association with an increase in NT-proBNP, and decreased eGFR (Figure 1A). sST-2 increased and MMP-2 decreased in association with an increase in E/E and LA volume (Figure 1B). There was also a direct relationship between sST-2 and Gal-3 (r=0.24, P<0.001; Figure 1C).

Table 2.

Correlations Between Biomarker and Demographic/Echocardiographic Data

| ST2

|

Galectin

|

MMP2

|

PIIINP

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P | R | P | R | P | R | P | |

| NT-proBNP | 0.19 | 0.002 | 0.17 | 0.004 | 0.31 | <0.001 | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| eGFR | −0.16 | 0.005 | −0.50 | <0.001 | −0.19 | 0.002 | −0.14 | 0.07 |

| SBP | −0.03 | 0.64 | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.01 | 0.92 | −0.04 | 0.60 |

| E′ | 0.07 | 0.31 | −0.04 | 0.51 | 0.07 | 0.31 | 0.07 | 0.38 |

| E/A | 0.12 | 0.11 | −0.04 | 0.57 | 0.24 | 0.003 | −0.02 | 0.84 |

| E/E′ | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.70 |

| LA volume | 0.25 | <0.001 | −0.01 | 0.87 | 0.14 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.65 |

A indicates atrial contraction induced diastolic filling velocity wave; E, early diastolic filling velocity; E′, early diastolic myocardial velocity; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LA, left atrium; MMPs, matrix metaloproteinases, NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; PIIINP, collagen III N-terminal propeptide; SBP, systolic blood pressure; and sST-2, soluble form of ST2 (an interleukin-1 receptor family member).

Figure 1.

A, Relationship between ln(sST-2) and ln(NT-proBNP) in patients with heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction; Spearman correlation r=0.19, P=0.002. B, Relationship between ln(sST2) and left atrial volume (LAV) in patients with heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction; correlation r=0.25, P=0.002. C, Relationship between ln(sST2) and ln(Gal-3) in patients with heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction; correlation r=0.23, P<0.0001. ; Gal-3 indicates galectin 3; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; and sST-2, soluble suppressor of tumorigenicity-2.

In a multivariable model after adjusting for age, sex, NYHA class, history of atrial fibrillation, diastolic blood pressure, eGFR, log NT-proBNP, E/E′, and LA volume, only female sex (coefficient, −0.27 [95% CI, −0.40 to −0.14]; P<0.001), NYHA class (coefficient, 0.24 [0.09 to 0.39]; P=0.002), and LA volume (coefficient, 0.003 [0.0004 to 0.005]; P=0.02) were statistically significantly associated with higher sST2. Only female sex (coefficient, 0.168 [0.004–0.332]; P=0.04) and log NT-proBNP (coefficient, 0.10 [0.01–0.19]; P=0.03) were associated with baseline PIIINP. Lower diastolic blood pressure was associated with higher MMP-2 levels at baseline (coefficient, −0.014 [−0.023 to −0.006]; P=0.001), whereas lower eGFR was associated with higher Gal-3 (coefficient, −0.008 [−0.011 to −0.006]; P<0.001).

Relationship Between Biomarkers and LCZ696 Treatment

The relationship between biomarkers and the effects of LCZ696 on the primary study end point (change in NT-proBNP after 12 weeks of treatment) and the secondary study end point (change LA volume from baseline after 36 weeks of treatment) were examined. There were no treatment interactions between LCZ696 and changes in NT-proBNP at 12 weeks (primary end point) for any of the 4 biomarkers: MMP-2 (interaction P=0.40), PIIINP (interaction P=0.14), Gal-3 (interaction P=0.32), or sST2 (interaction P=0.63). In addition, there were no treatment interactions between LCZ696 and changes in NT-proBNP at 36 weeks for any of the 4 biomarkers: MMP-2 (interaction P=0.09), PIIINP (interaction P=0.5), Gal-3 (interaction P=0.2), or sST2 (interaction P=0.99). However, there was an interaction between the response to treatment with LCZ696 compared with valsartan on change in LA volume at 36 weeks and baseline values of sST-2 (interaction P=0.07) and Gal-3 (interaction P=0.04). There was no interaction with PIIINP levels (interaction P=0.79) or MMP2 (interaction P=0.61).

We further explored the interaction with sST-2 and Gal-3 by dividing patients into 2 groups, for those above and below the observed baseline median value of sST-2 (≥33.0 versus <33.0 ng/mL) or Gal-3 (≥17.8 versus <17.8 ng/mL). The effect on change in LA volume from baseline differed between LCZ696 and valsartan (Figure 2). In patients with a baseline value of sST-2 above the median, 36 weeks of treatment with LCZ696 did not result in a significant change in LA volume from baseline compared with valsartan (difference, −1.5; 95% CI, −7.8 to 4.8; P=0.6). Similarly in patients with a baseline value of Gal-3 above the median, treatment with LCZ696 did not result in a significant change in LA volume from baseline compared with valsartan (difference, −1.8, 95% CI, −7.6 to 4.0; P=0.5). In patients with a baseline value of sST-2 or Gal-3 below the median, 36 weeks of treatment with LCZ696 resulted in a statistically significantly larger change from baseline in LA volume compared with valsartan (in those with sST-2 values below median, the difference in treatment effect between LCZ696 versus valsartan was −9.9; 95% CI, −15.1 to −4.8; P<0.0001, in those with Gal-3 values below the median treatment effect between LCZ696 versus valsartan was median difference −10.3; 95% CI, −15.6 to −5.0; P<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Change from baseline in left atrial volume (LAV) produced by treatment with LCZ696 vs valsartan in those with a baseline value of soluble form of ST2 (sST-2) and galectin 3 (Gal-3) above and below the median. When patients were divided into 2 groups, above and below the baseline median value of sST-2 or Gal-3, the effect on change in LA volume produced LCZ696 vs valsartan differed; in patients with a baseline value of sST-2 or Gal-3 above the median, treatment with LCZ696 did not result in a significant change in LA volume; in patients with a baseline value of sST-2 or Gal-3 below the median, treatment with LCZ696 resulted in a decrease in LA volume after 36 weeks of treatment compared with baseline.

For both patients with an NT-proBNP less than the median (difference, −4.1; 95% CI, −9.0 to 0.7; P=0.09) and patients with an NT-proBNP greater than the median (difference, −6.0; 95% CI, −12.0 to 0.1; P=0.053), treatment with LCZ696 resulted in a numerically greater reduction in LA volume from baseline compared with valsartan. A formal test of the interaction between randomized treatment and baseline NT-proBNP was not statistically significant (P for interaction=0.12). For patients with an eGFR less than the median (difference, −2.8; 95% CI, −7.7 to 2.1; P=0.26) and patients with an eGFR greater than the median (difference, −8.8; 95% CI, −15.0 to −2.6; P=0.006), treatment with LCZ696 resulted in a numerically greater reduction in LA volume from baseline compared with valsartan. This change was statistically significant for the group with an eGFR greater than the median. However, a formal test of interaction between randomized treatment and baseline eGFR was not statistically significant (P for interaction=0.58).

Interactions between LCZ696 and all other echocardiographic measurements of cardiac structure and function for the 4 biomarkers examined in this study were not performed because they were not listed as a priori end points and because our previous published studies showed that LCZ696 did not result in a change in any of these other echocardiographic parameters.13

There were no significant differences in any of the 4 biomarker values (sST-2, Gal-3, MMP-2, or PIIINP) between patients treated with valsartan versus LCZ696 at baseline or after 12 or 36 weeks of treatment (Table 3). This was true for the patient group as a whole and for subgroups with baseline sST-2 and Gal-3 above and below the observed median values. Comparing baseline biomarker values to after treatment values, MMP-2 increased significantly in both valsartan- and LCZ696-treated patients at week 36 versus baseline (P<0.001); there were no significant changes in the other 3 biomarkers comparing baseline with after treatment values.

Table 3.

Serial Measurements of Plasma Biomarkers

| sST2 | Galectin-3 | MMP-2 | PIIINP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| Sample Size | 296 | 294 | 247 | 178 |

| All | 33.0 (24.6–48.1) | 17.8 (14.1–22.8) | 188 (156–231) | 5.6 (4.3–6.9) |

| Valsartan | 33.8 (25.2–48.1) | 16.9 (14.0–22.4) | 188 (156–244) | 5.6 (4.3–6.8) |

| LCZ696 | 32.2 (24.3–47.8) | 18.9 (14.4–23.3) | 187 (150–225) | 5.5 (4.4–7.2) |

| 12 wk | ||||

| Sample Size | 262 | 250 | 244 | |

| All | 30.7 (23.4–44.7) | 17.0 (13.9–22.1) | 191 (155–234) | |

| Valsartan | 31.0 (23.9–44.4) | 17.1 (13.9–21.2) | 194 (150–243) | |

| LCZ696 | 29.8 (23.3–45.8) | 16.9 (14.2–22.2) | 189 (158–222) | |

| 36 wk | ||||

| Sample Size | 211 | 214 | 241 | 182 |

| All | 33.4 (23.5–48.4) | 16.8 (13.8–21.9) | 253 (208–318) | 5.3 (4.2–7.1) |

| Valsartan | 35.2 (23.6–45.1) | 16.8 (13.8–21.2) | 261 (212–334) | 5.4 (4.1–7.0) |

| LCZ696 | 31.4 (23.5–50.4) | 17.0 (13.8–22.2) | 248 (206–303) | 5.3 (4.2–7.2) |

All data are median (interquartile range) and in units of ng/mL. MMPs indicates matrix metaloproteinases; PIIINP, collagen III N-terminal propeptide; and sST-2, soluble form of ST2 (an interleukin-1 receptor family member).

History of atrial fibrillation was not associated with change in LA volume at 36 weeks P=0.12 and there was no interaction between randomized treatment and history of atrial fibrillation on change in LA volume P=0.44. In addition, for subjects with AF on ECG at baseline, the respective P values were also nonsignificant at 0.39 and 0.52.

Discussion

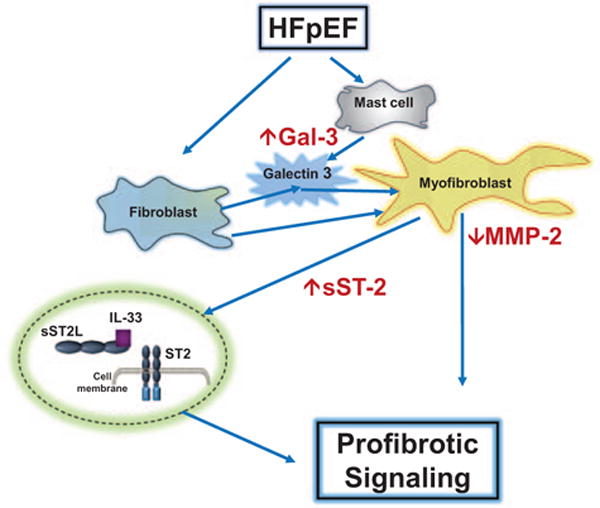

Data from this study support several novel and hypothesis generating findings. First, we found that patients with HFpEF had values of circulating biomarkers that may reflect a profibrotic state. Gal-3 and sST-2 were increased and MMP-2 was decreased. Gal-3 and sST-2 have been shown to increase collagen synthesis in cardiac fibroblasts and MMP-2 has been shown to cause collagen degradation2 (Figure 3). In aggregate, the directional changes in these biomarkers might be expected to be associated with an increase in myocardial collagen content. This study adds important, novel, clinically relevant data in a group of patients in which there is a large gap in knowledge. In particular, the panel of specific biomarkers used in this study has not been examined together in previous clinical studies or randomized clinic trials of patients with HFpEF. In addition, PARAMOUNT represents the only phase II randomized clinic trial of patients with HFpEF in which the prespecified primary end points have been positively improved by the therapy being tested. This provided a unique opportunity to examine the purposes proposed and test the hypotheses stated in this study.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of mechanisms suggested by changes in circulating biomarkers. Increased galectin 3 (gal-3) secreted by mast cells may contribute to transdifferentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. Increased soluble form of ST2 (sST-2) may contribute to ST-2 profibrotic signaling. Decreased matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) may contribute to less collagen degradation. In aggregate, these changes may contribute to increased myocardial extracellular matrix (ECM) collagen and fibrosis and may be reflected by the changes measured in circulating biomarkers. HFpEF indicates heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; and IL, interleukin.

The differences between biomarkers in the current HFpEF patients and referent controls are concordant with trends found in the limited number of other studies that included patients with HFpEF. For example, in studies including patients with HFpEF, sST-2 median values ranged from ≈25 to 30 ng/mL2,29–31 and Gal-3 median values ranged from ≈12 to 14 ng/mL.2,21,22,31 Variations in inclusion/exclusion criteria creating differences in population characteristics, comorbidity distribution, and severity of HF are likely responsible for small differences between studies.

For both sST-2 and Gal-3, there are Food and Drug Administration approved partition values that can be used in risk assessment analyses to predict morbid and mortal outcomes. When sST-2 is >35 ng/mL or Gal-3 is >17.8 ng/mL, there is an increase in risk. It should be noted; however, that both of these partition values were established from studies such as HF-ACTION and others in which patients with HFrEF were exclusively or dominantly the focus of study. It is fortuitous that the median values for these 2 biomarkers in this study are identical to or close to the Food and Drug Administration approved partition values. Therefore, these data lend credence to the important biomarker observations made in this study of patients with HFpEF in PARAMOUNT.

Second, we found that biomarker levels correlated with indices of disease severity. The presence of more severe HFpEF is generally indicated by higher levels of NT-proBNP, diastolic function (such as E/E′ and LAV) and decreased renal function.2,5,32–35 In this study, there was a direct relationship between sST-2 and each of these indices of disease severity; there was an inverse relationship with MMP-2. Thus, although each of the patients enrolled in PARAMOUNT had the clinical syndrome of HFpEF, those with the more severe disease had a biomarker pattern associated with a more profibrotic milieu. Although these interactions described in this study may have been expected, they have never been previously examined in a substantially sized study of patients with HFpEF. The interactions defined help to clarify signaling pathways that contribute to fibrosis-induced (and probably inflammation induced) abnormalities in structure and function in patients with HFpEF.

Third, the baseline pretreatment values of sST-2 and Gal-3 may have modified the response to LCZ696, specifically reduction in LA volume but not in NT-proBNP. Patients who had levels of sST-2 and Gal-3 below the observed median value showed a greater LA volume response to LCZ696 than those with sST-2 and Gal-3 above the median. These data are clearly not conclusive; however, they do allow the generation of important new hypotheses, particularly concerning the mechanisms underlying HFpEF and the effects of LCZ696 on these mechanisms. It is possible that patients with less severe myocardial fibrosis may be more responsive to treatment, particularly during a short period of treatment. Changes in LV structural remodeling may not be detectable until treatment has been continued for at least 12 months. Confirmation of these findings in a larger patient cohort and extension of treatment duration will clearly be needed in future studies to make more definitive conclusions. These kind of analyses are planned for Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ARB Global Outcomes in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (PARAGON-HF).

There are several possible factors that contribute to the fact that baseline biomarkers modified the response to LCZ696 on LAV but not to NT-proBNP. For example, changes in natriuretic peptides and changes in left atrial structure/function may reflect different but interdependent aspects of the pathophysiological mechanisms that underlie HFpEF. As presented in a previously published figure, LV diastolic filling pressures can be changed rapidly as a result of intravascular volume shifts and a change in operative compliance.2 This hemodynamic change may be best reflected by changes in natriuretic peptides. LV diastolic filling pressures can also be changed more slowly by progressive fibrosis and a change in overall chamber compliance.2 This structural change may be best reflected by changes in LAV. LCZ696 is likely to act on both of these mechanisms. Its direct diuretic, unloading, hemodynamic effect would be expected to rapidly reduce filling volume, operative compliance, and NT-proBNP and to do so without needed to also affect structural changes in myocardial extracellular matrix collagen or LAV. Therefore, the extent of fibrosis (as reflected by sST-2 or Gal-3) should not modify the effects of LCZ696 on changes in NT-proBNP. By contrast, the effects of LCZ696 on the regression of fibrosis would be expected to occur over longer time periods. Therefore, patients with less fibrosis (as reflected by lower values of sST-2 or Gal-3) may respond more quickly with a decrease in overall chamber compliance and a resultant decrease in LAV because there was simply less fibrosis to regress. Patients with more fibrosis may take longer than 6 to 9 months to respond to LCZ696; however, this finding does not necessarily signal the absence of a response. There are few studies that document the time course of regression of fibrosis in pathophysiological processes that undergo treatments that effectively correct the pathophysiological abnormalities. However, perhaps the best example is the effects of aortic valve replacement in patients with aortic valve stenosis. In these studies, the complete reversal of LV fibrosis was time dependent and progressive during a 2- to 4-year period after aortic valve replacement.36 Thus, the interplay between changes in hemodynamic and structural factors (and other factors) may contribute to the findings presented in this study.

Fourth, during the 36-week course of this study, sST-2, Gal-3, MMP-2, or PIIINP did not change in either the valsartan- or LCZ696-treated groups. The significance of this finding is not entirely clear. The same possible factors listed above may be applicable such as the length of the treatment period may be too short to see significant changes in these biomarkers. Conversely, it is possible that this particular set of biomarkers may have greater use as diagnostic, prognostic, and severity of illness indices rather than indices reflecting response to therapy.

Biomarkers Reflecting a Profibrotic State

Fibrillar collagen content can be altered by changes in the balance in the following processes: collagen synthesis, post-synthetic processing, and degradation. Biomarkers reflecting changes in these processes or their determinants were examined in PARAMOUNT.2,5–7 For example, Gal-3, a β-galactoside–binding lectin, secreted by macrophages, may act to increase fibroblast proliferation, activity, transformation into myofibroblast, and increase collagen synthesis.25–28,37–43 Likewise, soluble ST2, by acting as a decoy, prevents binding of IL-33 to membrane-bound ST2 and results in increased collagen synthesis (Figure 3). Therefore, both Gal-3 and sST2 induced increase in collagen synthesis would be expected to be reflected in an increase in levels of collagen propeptides, such as PIIINP (procollagen III N-terminal propeptide). However, in the presence of what seem to be profibrotic stimuli, we did not see changes in PIIINP. It is likely that the most important changes in myocardial collagen homeostasis involve a change in collagen I rather than collagen III, thus limiting the sensitivity of PIIINP versus measurements of collagen I propeptides. In addition to changes in synthesis, changes in degradation may affect collagen content. Insoluble collagen fibril degradation is caused by proteases such as MMPs, of which there are >29 known members.5–11 Only MMP-2 was measured in PARAMOUNT; lower values seen in patients with HFpEF suggests decreased degradation rates; however, measurement of this single MMP particularly without measurement of tissue inhibitors of MMPs does not fully characterize the stoichiometric balance of this enzyme system.

Study Limitations

We readily acknowledge that comparing biomarker data from this study with nonsimultaneous, historic, previously published referent controls imposes clear limitations. Although a referent control group was not included in the design of the PARAMOUNT study, the previously published referent control subjects used for comparison were taken from subjects with an age, sex, and race distribution similar to this study population but with no evidence of active cardiovascular disease. In addition, the methodologies used in this study to measure biomarkers were either identical to or equivalent to the methods used in previously published studies. The small differences in methodologies are not likely to impose significant differences between study analyses.

Measurements of circulating biomarkers are not direct measurements of myocardial collagen homeostasis. Our analysis assumes that biomarkers are representatively excreted in a manner measureable in the circulation and that their predominant source is the myocardium. PARAMOUNT was designed with exclusion criteria that limited comorbid conditions that would produce nonmyocardial sources of circulating biomarkers that reflect changes in collagen homeostasis, such as severe renal, pulmonary, or hepatic fibrosis.

Conclusions

In patients with HFpEF, biomarkers that reflect collagen homeostasis correlated with the presence and severity of disease and underlying pathophysiology, and may modify the structural response to treatment.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a clinical syndrome that has been associated with changes in the extracellular matrix. The purpose of this analysis was to examine a selected portfolio of postulated profibrotic biomarkers in a defined population of HFpEF, relate these biomarkers to demographic characteristics, changes in left ventricular structure and function, severity of disease, and response to treatment. Data from this analysis support several novel and hypothesis-generating findings. First, patients with HFpEF have circulating biomarkers that reflect a profibrotic state. Galectin 3 and soluble form of ST2 were increased and matrix metalloproteinase-2 was decreased. In aggregate, these directional changes in these biomarkers might be expected to be associated with an increase in myocardial collagen content. Second, biomarker levels correlate with indices of disease severity. Although each of the patients enrolled in the Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ARB on Management of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction trial (PARAMOUNT) had the clinical syndrome of HFpEF, those with the more severe disease had a biomarker pattern associated with a more profibrotic milieu. Third, the baseline pretreatment values of soluble form of ST2 and galectin 3 may have modified the response to LCZ696, specifically reduction in left atrial volume. Patients who had levels of soluble form of ST2 and galectin 3 below the observed median value showed a greater left atrial volume response to LCZ696 than those with soluble form of ST2 and galectin 3 above the median. In patients with HFpEF, biomarkers that reflect collagen homeostasis correlated with the presence and severity of disease and underlying pathophysiology, and may modify the structural response to treatment.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by Novartis.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration—URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT00887588.

Guest Editor for this article was W.H. Wilson Tang, MD.

The Data Supplement is available at http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002551/-/DC1.

Circ Heart Fail is available at http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org

Disclosures

Drs Zile, Solomon, Pieske, Voors, and McMurray have received research support and have consulted for Novartis. Dr Jhund has consulted for Novartis. Drs Shi, Prescott, and Lefkowitz are employees of Novartis. The other authors report no conflicts.

References

- 1.Ahmad T, Fiuzat M, Pencina MJ, Geller NL, Zannad F, Cleland JG, Snider JV, Blankenberg S, Adams KF, Redberg RF, Kim JB, Mascette A, Mentz RJ, O’Connor CM, Felker GM, Januzzi IL. Charting a roadmap for heart failure biomarker studies. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2:477–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zile MR, Baicu CF. Biomarkers of diastolic dysfunction and myocardial fibrosis: application to heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2013;6:501–515. doi: 10.1007/s12265-013-9472-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Kimmenade RR, Januzzi JL., Jr Emerging biomarkers in heart failure. Clin Chem. 2012;58:127–138. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.165720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braunwald E. Biomarkers in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2148–2159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zile MR, Desantis SM, Baicu CF, Stroud RE, Thompson SB, McClure CD, Mehurg SM, Spinale FG. Plasma biomarkers that reflect determinants of matrix composition identify the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:246–256. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.958199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spinale FG, Zile MR. Integrating the myocardial matrix into heart failure recognition and management. Circ Res. 2013;113:725–738. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spinale FG, Janicki JS, Zile MR. Membrane-associated matrix proteolysis and heart failure. Circ Res. 2013;112:195–208. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.266882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yarbrough WM, Baicu C, Mukherjee R, Van Laer A, Rivers WT, McKinney RA, Prescott CB, Stroud RE, Freels PD, Zellars KN, Zile MR, Spinale FG. Cardiac-restricted overexpression or deletion of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-4: differential effects on left ventricular structure and function following pressure overload-induced hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:H752–H761. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00063.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zile MR, Baicu CF, Stroud RE, Van Laer AO, Jones JA, Patel R, Mukherjee R, Spinale FG. Mechanistic relationship between membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase and the myocardial response to pressure overload. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:340–350. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baicu CF, Li J, Zhang Y, Kasiganesan H, Cooper G, IV, Zile MR, Bradshaw AD. Time course of right ventricular pressure-overload induced myocardial fibrosis: relationship to changes in fibroblast post-synthetic procollagen processing. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H1128–H1134. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00482.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zile MR, Baicu CF, Stroud RE, Van Laer A, Arroyo J, Mukherjee R, Jones JA, Spinale FG. Pressure overload-dependent membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase induction: relationship to LV remodeling and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1429–H1437. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00580.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butler J, Fonarow GC, Zile MR, Lam CS, Roessig L, Schelbert EB, Shah SJ, Ahmed A, Bonow RO, Cleland JG, Cody RJ, Chioncel O, Collins SP, Dunnmon P, Filippatos G, Lefkowitz MP, Marti CN, McMurray JJ, Misselwitz F, Nodari S, O’Connor C, Pfeffer MA, Pieske B, Pitt B, Rosano G, Sabbah HN, Senni M, Solomon SD, Stockbridge N, Teerlink JR, Georgiopoulou VV, Gheorghiade M. Developing therapies for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: current state and future directions. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2:97–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon SD, Zile M, Pieske B, Voors A, Shah A, Kraigher-Krainer E, Shi V, Bransford T, Takeuchi M, Gong J, Lefkowitz M, Packer M, McMurray JJ. Prospective comparison of ARNI with ARB on Management Of heart failUre with preserved ejectioN fracTion (PARAMOUNT) Investigators. The angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a phase 2 double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1387–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJ, Chamber Quantification Writing Group; American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee; European Association of Echocardiography Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraigher-Krainer E, Shah AM, Gupta DK, Santos A, Claggett B, Pieske B, Zile MR, Voors AA, Lefkowitz MP, Packer M, McMurray JJ, Solomon SD, PARAMOUNT Investigators Impaired systolic function by strain imaging in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christenson RH, Duh SH, Wu AH, Smith A, Abel G, deFilippi CR, Wang S, Adourian A, Adiletto C, Gardiner P. Multi-center determination of galectin-3 assay performance characteristics: anatomy of a novel assay for use in heart failure. Clin Biochem. 2010;43:683–690. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coglianese EE, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Ho JE, Ghorbani A, McCabe EL, Cheng S, Fradley MG, Kretschman D, Gao W, O’Connor G, Wang TJ, Januzzi JL. Distribution and clinical correlates of the interleukin receptor family member soluble ST2 in the Framingham Heart Study. Clin Chem. 2012;58:1673–1681. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.192153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dieplinger B, Januzzi JL, Jr, Steinmair M, Gabriel C, Poelz W, Haltmayer M, Mueller T. Analytical and clinical evaluation of a novel high-sensitivity assay for measurement of soluble ST2 in human plasma–the Presage ST2 assay. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;409:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu J, Snider JV, Grenache DG. Establishment of reference intervals for soluble ST2 from a United States population. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:1825–1826. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mueller T, Jaffe AS. Soluble ST2–analytical considerations. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(suppl 7):8B–21B. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edelmann F, Holzendorf V, Wachter R, Nolte K, Schmidt AG, Kraigher-Krainer E, Duvinage A, Unkelbach I, Düngen HD, Tschöpe C, Herrmann-Lingen C, Halle M, Hasenfuss G, Gelbrich G, Stough WG, Pieske BM. Galectin-3 in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: results from the Aldo-DHF trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:214–223. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.AbouEzzeddine OF, Haines P, Stevens S, Nativi-Nicolau J, Felker GM, Borlaug BA, Chen HH, Tracy RP, Braunwald E, Redfield MM. Galectin-3 in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. A RELAX trial substudy (Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibition to Improve Clinical Status and Exercise Capacity in Diastolic Heart Failure) JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manzano-Fernández S, Mueller T, Pascual-Figal D, Truong QA, Januzzi JL. Usefulness of soluble concentrations of interleukin family member ST2 as predictor of mortality in patients with acutely decompensated heart failure relative to left ventricular ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friões F, Lourenço P, Laszczynska O, Almeida PB, Guimarães JT, Januzzi JL, Azevedo A, Bettencourt P. Prognostic value of sST2 added to BNP in acute heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Clin Res Cardiol. 2015;104:491–499. doi: 10.1007/s00392-015-0811-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Motiwala SR, Szymonifka J, Belcher A, Weiner RB, Baggish AL, Gaggin HK, Bhardwaj A, Januzzi JL., Jr Measurement of novel biomarkers to predict chronic heart failure outcomes and left ventricular remodeling. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2014;7:250–261. doi: 10.1007/s12265-013-9522-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang YC, Yu CC, Chiu FC, Tsai CT, Lai LP, Hwang JJ, Lin JL. Soluble ST2 as a biomarker for detecting stable heart failure with a normal ejection fraction in hypertensive patients. J Card Fail. 2013;19:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhardwaj A, Januzzi JL., Jr ST2: a novel biomarker for heart failure. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2010;10:459–464. doi: 10.1586/erm.10.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah KB, Kop WJ, Christenson RH, Diercks DB, Henderson S, Hanson K, Li SY, deFilippi CR. Prognostic utility of ST2 in patients with acute dyspnea and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Clin Chem. 2011;57:874–882. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.159277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zile MR, Gottdiener JS, Hetzel SJ, McMurray JJ, Komajda M, McKelvie R, Baicu CF, Massie BM, Carson PE, I-PRESERVE Investigators Prevalence and significance of alterations in cardiac structure and function in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2011;124:2491–2501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.011031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah AM, Claggett B, Sweitzer NK, Shah SJ, Anand IS, O’Meara E, Desai AS, Heitner JF, Li G, Fang J, Rouleau J, Zile MR, Markov V, Ryabov V, Reis G, Assmann SF, McKinlay SM, Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD. Cardiac structure and function and prognosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: findings from the echocardiographic study of the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) Trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:740–751. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zile MR, Baicu CF, Ikonomidis JS, Stroud RE, Nietert PJ, Bradshaw AD, Slater R, Palmer BM, Van Buren P, Meyer M, Redfield MM, Bull DA, Granzier HL, LeWinter MM. Myocardial stiffness in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction: contributions of collagen and titin. Circulation. 2015;131:1247–1259. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, Claggett B, Clausell N, Desai AS, Diaz R, Fleg JL, Gordeev I, Harty B, Heitner JF, Kenwood CT, Lewis EF, O’Meara E, Probstfield JL, Shaburishvili T, Shah SJ, Solomon SD, Sweitzer NK, Yang S, McKinlay SM, TOPCAT Investigators Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1383–1392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uraizee I, Cheng S, Hung CL, Verma A, Thomas JD, Zile MR, Aurigemma GP, Solomon SD. Relation of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide with diastolic function in hypertensive heart disease. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26:1234–1241. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpt098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anand IS, Rector TS, Cleland JG, Kuskowski M, McKelvie RS, Persson H, McMurray JJ, Zile MR, Komajda M, Massie BM, Carson PE. Prognostic value of baseline plasma amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and its interactions with irbesartan treatment effects in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: findings from the I-PRESERVE trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:569–577. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.962654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKelvie RS, Komajda M, McMurray J, Zile M, Ptaszynska A, Donovan M, Carson P, Massie BM, I-Preserve Investigators Baseline plasma NT-proBNP and clinical characteristics: results from the irbesartan in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction trial. J Card Fail. 2010;16:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villari B, Vassalli G, Monrad ES, Chiariello M, Turina M, Hess OM. Normalization of diastolic dysfunction in aortic stenosis late after valve replacement. Circulation. 1995;91:2353–2358. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.9.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaggin HK, Szymonifka J, Bhardwaj A, Belcher A, De Berardinis B, Motiwala S, Wang TJ, Januzzi JL., Jr Head-to-head comparison of serial soluble ST2, growth differentiation factor-15, and highly-sensitive troponin T measurements in patients with chronic heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maisel A, Xue Y, van Veldhuisen DJ, Voors AA, Jaarsma T, Pang PS, Butler J, Pitt B, Clopton P, de Boer RA. Effect of spironolactone on 30-day death and heart failure rehospitalization (from the COACH Study) Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:737–742. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Boer RA, van der Velde AR, Mueller C, van Veldhuisen DJ, AAnker SD, Peacock WF, Adams KF, Maisel A. Galectin-3: a modifiable risk factor in heart failure. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2014;28:237–246. doi: 10.1007/s10557-014-6520-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Boer RA, Edelmann F, Cohen-Solal A, Mamas MA, Maisel A, Pieske B. Galectin-3 in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:1095–1101. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Velde AR, Gullestad L, Ueland T, Aukrust P, Guo Y, Adourian A, Muntendam P, van Veldhuisen DJ, de Boer RA. Prognostic value of changes in galectin-3 levels over time in patients with heart failure: data from CORONA and COACH. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:219–226. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu L, Ruifrok WP, Meissner M, Bos EM, van Goor H, Sanjabi B, van der Harst P, Pitt B, Goldstein IJ, Koerts JA, van Veldhuisen DJ, Bank RA, van Gilst WH, Silljé HH, de Boer RA. Genetic and pharmacological inhibition of galectin-3 prevents cardiac remodeling by interfering with myocardial fibrogenesis. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:107–117. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.971168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Boer RA, Lok DJ, Jaarsma T, van der Meer P, Voors AA, Hillege HL, van Veldhuisen DJ. Predictive value of plasma galectin-3 levels in heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. Ann Med. 2011;43:60–68. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.538080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.