Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

A growing literature suggests that missed nursing care is common in hospitals and may contribute to poor patient outcomes. There has been scant empirical evidence in pediatric populations. Our objectives were to describe the frequency and patterns of missed nursing care in inpatient pediatric settings and to determine whether missed nursing care is associated with unfavorable work environments and high nurse workloads.

METHODS:

A cross-sectional study using registered nurse survey data from 2006 to 2008 was conducted. Data from 2187 NICU, PICU, and general pediatric nurses in 223 hospitals in 4 US states were analyzed. For 12 nursing activities, nurses reported about necessary activities that were not done on their last shift because of time constraints. Nurses reported their patient assignment and rated their work environment.

RESULTS:

More than half of pediatric nurses had missed care on their previous shift. On average, pediatric nurses missed 1.5 necessary care activities. Missed care was more common in poor versus better work environments (1.9 vs 1.2; P < .01). For 9 of 12 nursing activities, the prevalence of missed care was significantly higher in the poor environments (P < .05). In regression models that controlled for nurse, nursing unit, and hospital characteristics, the odds that a nurse missed care were 40% lower in better environments and increased by 70% for each additional patient.

CONCLUSIONS:

Nurses in inpatient pediatric care settings that care for fewer patients each and practice in a professionally supportive work environment miss care less often, increasing quality of patient care.

Missed care is defined as “required patient care that is omitted or delayed in response to multiple demands or inadequate resources.”1 International evidence about missed nursing care, its antecedents, and consequences has been emerging.2,3 A review of 54 studies including data from 20 countries reported that missed care is prevalent; most nurses (55%–98%) reported missing ≥1 nursing activity. Teaching and emotional support were missed most frequently and physiologic needs least frequently. Organizational factors, including the work environment and staffing, were stronger predictors of missed care than nurse characteristics. In adult populations, missed care has been associated with poorer patient outcomes including satisfaction, adverse events, mortality, and readmission.4–7

Missed care is typically measured by self-report on a survey. Such self-reports are potentially biased (ie, underreported) because of the social undesirability of incomplete care. For this study, the missed care measure was worded as “activities necessary but left undone because you lacked the time to complete them.” This wording may lessen social undesirability and thereby yield more accurate reporting rather than underreporting. Both the definition and measure of missed care include the adjective required or necessary, which raises the question of whether there is nursing care that is not required. In both instances, we believe that the adjective is included to emphasize that something necessary was omitted.

Only 2 studies of missed nursing care have focused on pediatrics, specifically neonatal intensive care.8,9 One report on 9 NICUs in Quebec8 found that discharge planning, parental support and teaching, and comfort care were missed most frequently. Less care was missed in NICUs with better work environments. The second study reported on 230 certified NICU nurses.9 Half of the nurses reported missing care on their last shift. Nurses most frequently missed rounds, oral care, and educating and involving parents in care. The scant evidence from pediatrics undermines pediatric managerial efforts to address potential care lapses and related outcomes.

Missed care is theorized as a causal pathway linking poor work environments and staffing to poor clinical outcomes.10 The work environment has been defined as the organizational factors that influence professional nursing practice.11 Poor work environments undermine nurse effectiveness and efficiency. For example, poor collaboration between nurses and physicians may delay communication and care decisions. Nurses without sufficient resources or managerial support may not complete care or may rush care, and quality may be reduced. Without evidence that care is affected by poor work environments or staffing, it is difficult to garner sufficient support for improving these factors, given the challenges facing hospital leaders.

Work environments and nurse staffing in pediatrics have been studied rarely, in contrast to adult care. No studies have reported the frequency or patterns of missed nursing care in pediatrics generally, nor has the influence of work environment and staffing on missed care been analyzed. This study addresses these literature gaps.

The purpose of this article is to describe missed nursing care in pediatrics and to examine whether it differs across hospitals with better and poorer work environments and nurses with higher and lower workloads. We hypothesized that nurses with lower workloads or in hospitals with better environments would miss less care. These findings will inform practice to ensure that hospitalized children receive needed care.

Methods

Design, Data, and Sample

This cross-sectional study used registered nurse (RN) survey data from 2006 to 2008, representing acute care hospitals in California, Florida, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. A survey was fielded sequentially across these states. Surveys were sent to the home address of a random sample of licensed nurses. Two reminder postcards and 3 additional surveys were mailed to nonrespondents. No incentives were offered. Nurses indicated their place of employment from a hospital list. The response rate was 39%. No response rate was available for pediatric nurses because the sampling frame was state licensure rolls. A survey of nonrespondents, which achieved a 91% response rate with incentives, showed no bias in the data on key variables, including nurses’ evaluation of hospitals.12 The parent “Multi-State Nursing Care and Patient Safety Study” is described elsewhere.13 The university institutional review board granted approval.

Nurses included in this study provided direct patient care in a pediatric unit: NICU, PICU, or general pediatrics. Newborn nurseries were excluded to focus on care of sick children and for comparability with literature on missed care in adults. To retain only bedside care nurses, nurses who reported patient assignments of <1 or >7 were excluded.14 Hospitals with <3 respondents were excluded to obtain reliable estimates of the aggregate (hospital-level) work environment measure. Three respondents yielded acceptable intraclass correlation coefficients, as reported below.15 Our sample included general hospitals, freestanding children’s hospitals, and children’s hospitals within general hospitals.

Measures

The missed care questions were developed by survey methodologists and nurse researchers to capture essential nursing care activities. This measure has been used in 5 international samples10,16–19 and has exhibited predictive validity to patient satisfaction16,20 and readmissions.4 Nurses responded about whether 12 nursing care “activities were necessary, but left undone because you lacked the time to complete them” on the most recent shift worked. These activities ranged from adequate patient surveillance to comforting or talking with patients. The fractions of nurses who missed ≥1 activity and each activity were calculated. The number of activities missed was summed for each nurse.

Nurses also completed the 31-item Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI),11 a National Quality Forum–endorsed nursing performance measure.21 The PES-NWI has 5 subscales. After reliability and stability were established, data were aggregated to the hospital level. Hospital pediatric settings were classified into 3 subgroups, in accordance with earlier work.22 Hospitals with scores above the median for 4 or 5 subscales were classified as “better” environments, for 2 or 3 subscales as “mixed,” and for 0 or 1 subscale as “poor.”

Nurse workload was defined as the number of assigned patients on the last shift. Nurse characteristics included years of experience and whether the nurse held a bachelor of science degree in nursing (BSN). These characteristics were included as control variables in regression models because the nursing staff composition differs across pediatric hospital settings.23 Children’s hospitals have higher proportions of BSN-prepared RNs but less experienced RNs than pediatric RNs in general hospitals.23

Three characteristics from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey database24 were used to describe the sample and as controls in regression models. The number of acute care beds was categorized into 3 sizes. We used all beds rather than pediatric beds because this practice is conventional for describing the size distribution of hospital samples. Advanced technology capability was measured as capacity for open heart surgery or major organ transplant. Teaching status was classified into major, minor, and none, based on the medical resident-to-bed ratio. In regression models, controlling for these characteristics accounts partially for hospital financial resources that may influence work environments (more resources to support work environment improvement) and missed care (more resources to devote to improved operational efficiencies). Hospitals were classified as general, freestanding children’s, or children’s hospital within a hospital, based on state agency licensure information.23

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics described the nurse respondents and hospitals, nurse staffing, and work environments. Analysis of variance procedures compared differences in nurse-level missed care by work environment subgroups. The work environments of ICU and acute pediatrics were compared to assess whether they differed significantly. The frequency of missed care was averaged within each pediatric subgroup and graphed. Unadjusted and adjusted regression models estimated the association of the independent variables, work environment and nurse workload, to the dependent variable, nurse-level missed care. The “poor” work environment category was the referent. Logistic regression models assessed whether any care or particular activities were missed. Linear and negative binomial regression models assessed the sum of missed care. Negative binomial models are suited to skewed dependent variables such as the positively skewed sum of care activities missed. Given the consistent findings, the linear regression results were reported. The adjusted models controlled for nurse education and experience, nursing unit type, hospital characteristics, and hospital pediatric setting and accounted for nurse clustering within hospitals. To explore whether the effect of workload on missed care varied across work environment subgroups, an interaction term was tested. To explore whether the results were influenced by hospitals with NICU nurses only, we estimated models in a subsample with general pediatrics and PICU RNs. A final sensitivity analysis tested pediatric nurse staffing aggregated to the hospital. Statistical significance was set at P < .05 for a 2-tailed test. Analyses were conducted in Stata version 12.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

Results

The criteria yielded a sample of 2187 pediatric nurses in 223 hospitals. Most hospitals were >250-bed general hospitals with a teaching mission and advanced technology capability (Table 1). There were on average 9.8 respondents per hospital (range 3–68). On average nurses cared for 4 patients in general pediatrics versus 2 or 3 in intensive care. Nearly all nurses were female, and half were BSN-prepared. The nurses were very experienced, having worked 10 years on their unit. More than half the sample were NICU nurses, followed by general pediatrics, then PICU. We evaluated sample representativeness by generating percentages of NICU/PICU and general pediatrics nurses, using American Hospital Association data on numbers of NICU, PICU, and general pediatrics beds and our respective patients-per-nurse values. The sample distribution was similar to the national estimate, indicating sample representativeness of pediatric nurses in US hospitals.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Hospitals and Nurses

| Characteristics | n | % | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital characteristic (n = 223) | ||||

| Bed size | ||||

| ≤100 beds | 4 | 1.8 | — | — |

| >100 and ≤250 beds | 65 | 29.2 | — | — |

| >251 beds | 154 | 69.1 | — | — |

| Teaching hospital | ||||

| Major | 36 | 16.1 | — | — |

| Minor | 101 | 45.3 | — | — |

| Neither | 86 | 38.6 | — | — |

| High technology | 137 | 61.4 | — | — |

| Child hospital type | ||||

| General | 181 | 81.2 | — | — |

| Freestanding | 13 | 5.8 | — | — |

| Nested | 29 | 13.0 | — | — |

| State | ||||

| California | 99 | 44.4 | — | — |

| Pennsylvania | 45 | 20.2 | — | — |

| Florida | 44 | 19.7 | — | — |

| New Jersey | 35 | 15.7 | — | — |

| Patients per nurse | ||||

| Overall | — | — | 2.8 | 1.2 |

| Pediatric | — | — | 3.8 | 1.2 |

| PICU | — | — | 2.0 | 0.9 |

| NICU | — | — | 2.5 | 0.9 |

| Nurse characteristica | ||||

| Female | 2120 | 97.6 | — | — |

| Age | 2164 | — | 42.9 | 11.0 |

| Bachelor of science or higher degree in nursing | 1114 | 50.1 | — | — |

| Years of experience | ||||

| As an RN | 2164 | — | 16.5 | 11.0 |

| In hospital | 2097 | — | 11.8 | 9.6 |

| On unit | 2064 | — | 10.0 | 8.8 |

| Type of unit | ||||

| Pediatric | 613 | 28.0 | — | — |

| PICU | 342 | 15.6 | — | — |

| NICU | 1232 | 56.3 | — | — |

N ranged from 2064 to 2187 because of missing data.

Work environment measure statistics are listed in Table 2. All subscales had high internal consistency; 4 subscales exceeded conventional standards for hospital-level aggregation, that is, intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC[1,k]) of 0.60.15 The fifth subscale’s ICC was 0.51. The PES-NWI composite was 2.88, approaching the response of “agree” (3 on a scale of 1–4). The PES-NWI composite was identical for ICU and acute settings. The average hospital-level subscale SD was 0.37, representing an eighth of the scale range (0.37/3 = 0.12). This degree of typical variation demonstrates that pediatric environments vary across hospitals and have the potential to be modified.

TABLE 2.

Descriptive and Psychometric Statistics for the Practice Environment Scale of the PES-NWI

| Subscale | Mean | SD | α | ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staffing and resource adequacy | 2.80 | 0.70 | .85 | 0.60 |

| Nurse manager ability, leadership, and support of nurses | 2.65 | 0.81 | .87 | 0.62 |

| Nursing foundations for quality of care | 3.10 | 0.52 | .84 | 0.59 |

| Nurse participation in hospital affairs | 2.74 | 0.63 | .87 | 0.68 |

| Collegial nurse–physician relations | 3.11 | 0.68 | .87 | 0.51 |

| Composite | 2.88 | 0.54 | .86 | 0.61 |

n = 2149 nurses.

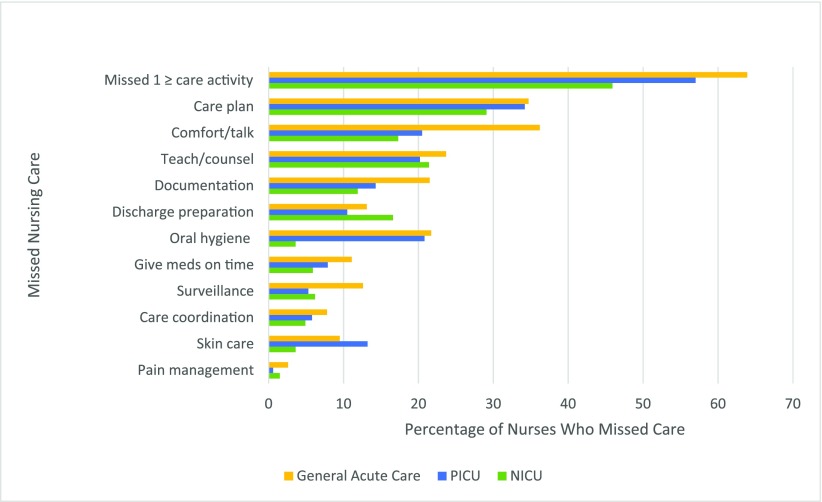

More than half the nurses left ≥1 care activity undone (Table 3). This percentage varied widely across activities, from 2% to 32%. Nurses missed a mean of 1.5 care activities (SD of 2.0). Care planning, comforting or talking, and teaching or counseling were missed most frequently. Pain management, treatments, and procedures were missed rarely. The pattern of missed care was similar across the 3 pediatric subgroups (Fig 1). In general, higher percentages of acute pediatrics nurses missed care, followed by PICU then NICU.

TABLE 3.

Distributions of Missed Nursing Care in Hospital Pediatric Settings, by Quality of Nurses’ Work Environment

| Work Environment Quality | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Poora | Mixedb | Betterc | Pd | |

| Variable | |||||

| No. hospitals | 223 | 84 | 62 | 77 | — |

| Percentage of hospitals | 100 | 37.7 | 27.8 | 34.5 | — |

| PES-NWI compositee | 2.86 | 2.58 | 2.88 | 3.15 | — |

| No. missed care activitiese | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.2 | .00 |

| Missed nursing care activitye | Prevalencef | ||||

| ≥1 activities | 52.7 | 61.3 | 52.1 | 45.6 | .00 |

| Develop or update care plans | 31.5 | 35.3 | 30.6 | 28.7 | .02 |

| Comfort or talk with patients | 23.1 | 30.4 | 24.6 | 15.8 | .00 |

| Teach or counsel patients and family | 21.9 | 25.9 | 21.9 | 18.4 | .00 |

| Adequately document nursing care | 15.0 | 18.3 | 15.7 | 11.7 | .00 |

| Prepare patients and families for discharge | 14.7 | 18.4 | 14.8 | 11.4 | .00 |

| Oral hygiene | 11.3 | 14.0 | 11.7 | 8.8 | .00 |

| Adequate patient surveillance | 7.8 | 12.1 | 6.5 | 4.9 | .00 |

| Administer medications on time | 7.7 | 11.5 | 6.2 | 5.4 | .00 |

| Coordinate patient care | 5.9 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 4.0 | .01 |

| Skin care | 6.8 | 8.5 | 6.5 | 5.4 | .04 |

| Treatments and procedures | 2.3 | 3.5 | 1.9 | 1.6 | .04 |

| Pain management | 1.7 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 1.2 | .14 |

Poor = 0 or 1 subscale above sample median.

Mixed = 2 or 3 subscales above sample median.

Better = 4 or 5 subscales above sample median.

Results were considered statistically significant at P < .05 for a 2-tailed test for a comparison of the frequency of care missed in the better versus the poor environment.

Values are means.

The prevalence of each missed nursing care activity is the proportion of nurses who reported that the required care was not done.

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of missed care by pediatric nurse subgroup.

The percentages of hospitals with poor, mixed, and better environments were 38%, 28%, and 35%. The work environment composite varied widely, from 3.15 in the better group to 2.58 in the poor group. In better environments, 46% of nurses missed care, whereas in poor environments, 61% missed care. The number of missed care activities differed significantly: 1.2 in better environments, 1.9 in poor. Likewise, for 11 of 12 activities, significantly more nurses in the poor environments missed the activity.

Results of the models regressing missed care on work environment categories and nurse workload, unadjusted and controlling for nurse, unit, and hospital characteristics, are listed in Table 4. Given the similarity in results, those of adjusted models are described. For missing any care, and for 9 of the 12 activities (results of individual activities not shown), the odds of missed care were significantly lower in better environments, almost half the odds (mean odds ratio [OR] across significant care activities was 0.58) of the poor environments. The largest work environment effects were observed for the timely administration of medications and patient surveillance (OR = 0.47). The remaining significant activities were comforting or talking to patients, teaching, care documentation, discharge preparation, oral hygiene, care coordination, and treatments or procedures. The sum of missed activities was 0.53 lower in better environments.

TABLE 4.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Logistic and Linear Regression Models With Results Displaying the Relationships Between Nurse Workload, the Quality of the Nurse Work Environment, and Missed Nursing Care

| Unadjusted Joint Model (n = 2187) | Joint Model Adjusting for Nurse and Hospital Characteristics (n = 2163) | |

|---|---|---|

| Any missed care | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Nurse workload | 1.56*** (1.43 to 1.70) | 1.70*** (1.51 to 1.90) |

| Mixed environment | 0.67** (0.51 to 0.89) | 0.64*** (0.50 to 0.82) |

| Better environment | 0.59*** (0.44 to 0.78) | 0.59*** (0.46 to 0.76) |

| Sum of missed care activities | Estimate (95% CI) | Estimate (95% CI) |

| Nurse workload | 0.44*** (0.36 to 0.52) | 0.50*** (0.41 to 0.60) |

| Mixed environment | −0.38** (−0.65 to −0.11) | −0.40*** (−0.62 to −0.18) |

| Better environment | −0.55*** (−0.78 to −0.32) | −0.53*** (−0.74 to −0.33) |

Models control for nurse characteristics (BSN or higher degree; years of RN experience) and hospital characteristics (bed size, technology status, teaching status, type of children’s hospital). Work environment variables are hospital level. Nurse workload is nurse level. The dependent variable is nurse level. For the work environment, the reference group is the “poor” work environment subgroup of hospitals with 0 or 1 subscale above the sample median. Results were considered statistically significant at P < .05 for a 2-tailed test. CI, confidence interval.

P < .01, ***P < .001.

Nurse workload was significantly associated with missing any care (OR = 1.70) and for 11 of 12 activities (results of individual activities not shown) (average OR of significant activities = 1.49, P = .00). An additional patient per nurse (∼1 SD) increased the odds of missing any care by 70%. An additional patient increased the sum of missed activities by 0.50 (about 0.25 SD).

In the subsample of 182 hospitals with general pediatric and PICU nurses, the results were almost identical. Only 6 activities were significant, probably because of the smaller sample. The interaction between work environment and nurse workload was insignificant. Hospital-level staffing was independently associated with a nurse missing any activity and with less than half of the particular activities.

Discussion

This is the first study to quantify missed nursing care in all pediatric hospital settings and show its relationship to hospital work environments and nurses’ patient load. Missed care, defined as not completing required nursing care, is common in inpatient pediatrics. In this large sample comprising 2187 pediatric nurses in 223 hospitals, more than half of pediatric nurses reported missing care on their last shift. Missed care in pediatrics is of particular concern, given the vulnerability of children, who may not be able to express their symptoms or get needed attention, especially when families are not present. Missed care happens in the most fundamental nurse responsibilities that probably affect patient outcomes, such as surveillance, pain management, and preparing patients for discharge.

Our results shed light on 3 important aspects of missed care in pediatrics: what is missed, how often, and why. The most commonly missed activities were care planning, comforting, and teaching. Overall, 15% of nurses missed discharge planning, a number that rose to 20% in poor environments. Missing teaching and discharge preparation may increase costly and unnecessary readmissions.25

Some activities missed infrequently may pose risks for patients. Although surveillance was rarely missed, notably 1 in 8 nurses working in poor environments reported not having the time to provide adequate surveillance. Acutely ill babies and children can deteriorate quickly, and inadequate surveillance may delay response to early clinical signs of distress and permanent harm.26

Our results documenting that nurses miss certain kinds of care more frequently, such as comfort, and others infrequently, such as pain management, are consistent with research about nurses making clinical decisions based on care hierarchies. Nurses prioritize imminent clinical concerns ahead of providing interpersonal teaching and support,27 but omitting interpersonal interventions can also have serious consequences. Compared with evidence from nurses caring for adults, we found that fewer pediatric nurses miss care (53% of pediatric nurses vs 73% of adult nurses), but the pattern of activities missed is similar.20

This article presents compelling data that the quality of the nurse work environment and staffing levels are associated with missed care. The multivariate results, controlling for hospital, unit type, and nurse factors, demonstrated that for nearly all activities, nurses with a lower patient load or in better environments were significantly less likely to miss care. An additional patient per nurse increased the odds 70% that the nurse missed any care. Nurses were 40% less likely to miss care in better environments. Our findings are consistent with evidence from 9 Quebec NICUs linking work environments to missed nursing care.8 An alternative interpretation of the association is that nurses exhausted by never finishing their work lead to a poor work environment. However, our work environment measure relies on nurse assessment of the presence of 31 organizational characteristics, none of which pertain to the completion of work. Aggregation of this measure to the hospital provides an organizational perspective that is unlikely to be driven by individual nurses’ likelihood of missing care.

Improving the work environment may be a useful strategy to reduce missed care. The American Nurses Credentialing Center’s Magnet Recognition Program provides an evidence-based blueprint for improving nurse work environments.28–31 Magnet recognition does not require a specific nurse staffing ratio but does require a guideline-based process of establishing safe staffing levels. The Magnet Recognition Program standard is designed “to ensure that RN assignments meet the needs of the patient population.”32 Our results demonstrating that care is missed imply that, when this happens, the needs of the patient population are not met. Missed care has been recommended as a dashboard measure to serve as an early warning that work environment and staffing are potentially inadequate and affecting care.33 Our results provide managers with work environment benchmarks to gauge the likely frequency of care missed on their units.

One may question whether missed care is necessarily harmful. Particular instances of missed care may not cause harm in the immediate moment, but care missed over an inpatient stay probably has a cumulative, detrimental impact. Delayed feedings in the NICU, for example, have been linked to longer lengths of stay.34 Some impacts of missed care may be evident only after discharge and reflected in readmission, as was documented in a large study of patients with heart failure.4 Research is needed exploring the effect of missed nursing care on pediatric outcomes.

Our cross-sectional design prevents causal inference. However, it is unlikely that missed nursing care creates poor work environments or increased patient loads. The age of the data is a limitation. However, these were the only data available on missed care by pediatric nurses. The parent data set uniquely comprises a representative sample of hospitals and nurses in 4 large states, accounting for 25% of US hospitalizations. Given the ongoing resource constraints in health care, the introduction of electronic health records necessitating more nurse time for documentation, and no obvious basis for shifting care hierarchies, there is no evidence to suggest that missed nursing care is not an important current problem.

The validity evidence supporting this missed care measure is limited. Nearly all research on missed care has relied on self-reports, whose reliability may be questioned. This article focuses on missed nursing care, yet the question refers to “activities left undone.” These semantic differences are likely to influence responses. However, if nurses are reluctant to report missed care, our findings may underestimate its actual prevalence.

Conclusions

Acutely ill children needing hospitalization are vulnerable to poor outcomes that could compromise their long-term well-being. Reducing missed care for hospitalized children by improving care environments and nurse staffing is feasible and necessary.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr Tim Cheney and Ms Myra Eckenhoff for their contributions to the manuscript.

Footnotes

Dr Lake provided statistical expertise, administrative, technical, and material support, and overall study supervision, obtained funding, designed and conceptualized the study, drafted the initial manuscript and revised it critically for important intellectual content; Dr de Cordova and Ms Singh designed and conceptualized the study and drafted the initial manuscript; Dr Barton was responsible for obtaining funding for this study, designed and conceptualized the study, and drafted the initial manuscript; Dr. Ely and Ms Roberts conceptualized the study and revised it critically for important intellectual content; Dr Aiken was responsible for acquiring the data used in this study, obtained funding, designed and conceptualized the study, and drafted the initial manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by grants to the Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research from the National Institute of Nursing Research (T32-NR-007104 and R01-NR-014855, L. Aiken, principal investigator) and from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Kalisch BJ, Landstrom GL, Hinshaw AS. Missed nursing care: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(7):1509–1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papastavrou E, Andreou P, Efstathiou G. Rationing of nursing care and nurse–patient outcomes: a systematic review of quantitative studies. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2014;29(1):3–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones TL, Hamilton P, Murry N. Unfinished nursing care, missed care, and implicitly rationed care: state of the science review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(6):1121–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carthon JM, Lasater KB, Sloane DM, Kutney-Lee A. The quality of hospital work environments and missed nursing care is linked to heart failure readmissions: a cross-sectional study of US hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(4):255–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalisch BJ, Xie B, Dabney BW. Patient-reported missed nursing care correlated with adverse events. Am J Med Qual. 2014;29(5):415–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schubert M, Clarke SP, Aiken LH, de Geest S. Associations between rationing of nursing care and inpatient mortality in Swiss hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(3):230–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schubert M, Glass TR, Clarke SP, et al. Rationing of nursing care and its relationship to patient outcomes: the Swiss extension of the International Hospital Outcomes Study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20(4):227–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rochefort CM, Clarke SP. Nurses’ work environments, care rationing, job outcomes, and quality of care on neonatal units. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(10):2213–2224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tubbs‐Cooley HL, Pickler RH, Younger JB, Mark BA. A descriptive study of nurse‐reported missed care in neonatal intensive care units. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(4):813–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ausserhofer D, Zander B, Busse R, et al. Prevalence, patterns and predictors of nursing care left undone in European hospitals: results from the multicountry cross-sectional RN4CAST study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(2):126–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lake ET. Development of the practice environment scale of the Nursing Work Index. Res Nurs Health. 2002;25(3):176–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith HL. A double sample to minimize bias due to nonresponse in a mail survey. Population Studies Center Working Papers. Available at: http://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1013&context=psc_working_papers. Accessed August 3, 2015

- 13.Aiken LH, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, Smith HL, Flynn L, Neff DF. Effects of nurse staffing and nurse education on patient deaths in hospitals with different nurse work environments. Med Care. 2011;49(12):1047–1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly DM, Kutney-Lee A, McHugh MD, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. Impact of critical care nursing on 30-day mortality of mechanically ventilated older adults. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1089–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glick WH. Conceptualizing and measuring organizational and psychological climate: pitfalls in multilevel research. Acad Manage Rev. 1985;10(3):601–616 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Kandari F, Thomas D. Factors contributing to nursing task incompletion as perceived by nurses working in Kuwait general hospitals. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(24):3430–3440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ball JE, Murrells T, Rafferty AM, Marrow E, Griffiths P. “Care left undone” during nursing shifts: associations with workload and perceived quality of care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(2):116–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Bruyneel L, Van den Heede K, Sermeus W; RN4CAST Consortium. Nurses’ reports of working conditions and hospital quality of care in 12 countries in Europe. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(2):143–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu XW, You LM, Zheng J, et al. Nurse staffing levels make a difference on patient outcomes: a multisite study in Chinese hospitals. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;44(3):266–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lake ET, Germack HD, Viscardi MK. Missed nursing care is linked to patient satisfaction: a cross-sectional study of US hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(7):535–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Quality Forum. Practice Environment Scale–Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI) (composite and five subscales). Available at: www.qualityforum.org/QPS/0206. Accessed April 15, 2016

- 22.Liu K, You L-M, Chen S-X, et al. The relationship between hospital work environment and nurse outcomes in Guangdong, China: a nurse questionnaire survey. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(9–10):1476–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cimiotti JP, Barton SJ, Chavanu Gorman KE, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. Nurse reports on resource adequacy in hospitals that care for acutely ill children. J Healthc Qual. 2014;36(2):25–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Hospital Association. AHA Annual Survey Database 2008 Edition. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss M, Johnson NL, Malin S, Jerofke T, Lang C, Sherburne E. Readiness for discharge in parents of hospitalized children. J Pediatr Nurs. 2008;23(4):282–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akre M, Finkelstein M, Erickson M, Liu M, Vanderbilt L, Billman G. Sensitivity of the Pediatric Early Warning Score to identify patient deterioration. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/125/4/e763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patterson ES, Ebright PR, Saleem JJ. Investigating stacking: how do registered nurses prioritize their activities in real-time? Int J Ind Ergon. 2011;41(4):389–393 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Upenieks VV, Sitterding M. Achieving magnet redesignation: a framework for cultural change. J Nurs Adm. 2008;38(10):419–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McHugh MD, Kelly LA, Smith HL, Wu ES, Vanak JM, Aiken LH. Lower mortality in magnet hospitals. Med Care. 2013;51(5):382–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drafahl B, Beyer L, Chow C. Do you know the way to excellence? Nurs Manage. 2012;43(7):15–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kutney-Lee A, Stimpfel AW, Sloane DM, Cimiotti JP, Quinn LW, Aiken LH. Changes in patient and nurse outcomes associated with magnet hospital recognition. Med Care. 2015;53(6):550–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Nurses Credentialing Center. Application Manual: Magnet Recognition Program. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Credentialing Center; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 33.VanFosson CA, Jones TL, Yoder LH. Unfinished nursing care: an important performance measure for nursing care systems. Nurs Outlook. 2016;64(2):124–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tubbs-Cooley HL, Pickler RH, Meinzen-Derr JK. Missed oral feeding opportunities and preterm infants’ time to achieve full oral feedings and neonatal intensive care unit discharge. Am J Perinatol. 2015;32(1):1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]