Abstract

Background

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a common disease with a high mortality. Many animal models have been developed to further understand the pathogenesis of the disease, but no large animal model has been developed to investigate the autoimmune aspect of AAA formation. The aim of this study was to develop a large animal model for abdominal aortic aneurysm induction through autoimmunity by performing sheep-to-pig xenotransplantation.

Methods

Six pigs underwent a xenotransplantation procedure where the infrarenal porcine aorta was replaced by a decellularized sheep aorta. In the following 47 days, the AP-diameter of the xenografts was measured using ultrasound once a week. All xenografts were harvested for histological analyses.

Results

All the xenografts formed aneurysms with a mean increase in AP-diameter of 80.98 ± 30.20% (p < 0.005). The ultrasound measurements demonstrated a progressive aneurysmal expansion with no sign of halting towards the end of the follow-up period. Histology showed destruction of tunica media and the elastic tissue, neointimal hyperplasia, adventitial thickening with neovascularization, infiltration of lymphocytes and granulocytes, and in some cases intramural haemorrhaging.

Conclusion

We developed a novel large animal AAA model by infrarenal aortic sheep-to-pig xenograph transplantation resulting in autoimmune AAA induction with continuously progressive aneurysmal growth. This model can be used to provide a better understand the autoimmune aspect of AAA formation in large animals.

Keywords: Abdominal aortic aneurysm, Porcine model, Sheep-to-pig xenotransplantation, Autoimmunity

Highlights

-

•

An Experimental study of decellularized aortic xenografts from sheeps implanted into the abdominal aorta in pigs.

-

•

The study shows that it’s possible to induce autoimmune AAA with progressive expansion in pigs.

-

•

The induced autoimmune AAAs in pigs where presence already at day 28.

-

•

Intraluminal mural thrombus development also occurred in this study.

-

•

The study also examined the efficiency of SDS with DNase-I as decellularizing detergents on sheep aorta.

1. Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is an irreversible dilatation of the abdominal aorta with an anteroposterior diameter of at least 30 mm in adult humans. AAAs are often asymptomatic and discovered as incidental findings by computer tomography imaging for unrelated health problems, or when the AAA ruptures leading to a surgical emergency with a mortality of 50–80% [1], [2].

Autoimmunity appears to play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of AAA as a result of systemic autoimmune responses [1]. Hallmark features of autoimmunity in AAAs are the presence of Russell bodies, chronic inflammation with infiltration of oligoclonal T and B cells, elevated cytokines, increased levels of autoantibodies, and an association with HLA molecules [2], [3], [4]. Presumed autoantigens have been identified in the aortic wall, such as microfibrillar protein called aortic aneurysm-associated protein-40 (AAAP-40) [2], [3]. Several microorganisms that share sequence similarities with AAAP-40 have also been linked to aneurysm development [2], [3], [4]. By molecular mimicry, cross-reactivity of epitopes has been suggested to be the mechanism behind the T-cell inflammatory response and the autoimmune induction of AAA. In support, anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs have already been tested in both animal models and human observational studies, revealing a reduced expansion of AAAs [2], [3]. However, the specific targets are still unknown, and further investigation is needed before medical therapy of AAAs can be marketed. Although there are many well established rodent models of AAA [5] the current techniques to induce experimental AAAs in large animals include chemical induction with elastase alone or in combination with collagenase or calcium chloride, mechanical induction with balloon dilatation and surgical induction with stenotic banding or vein patching, or combinations of these [6], [7], [8]. These models seem to come to a halt at 75–100% increased dilatations as a sign of healing [7], [9]. Based on the hypothesis about the formation of AAA mediated by autoimmunity, the aim of this study was to develop a novel autoimmune AAA model by performing a sheep-to-pig xenotransplantation. Thus, introducing an immune rejection response following implantation of tissue from a foreign animal species [6]; however, the xenograft was decellularized upon implantation to minimize the risk of acute rejection.

2. Materials and methods

The experimental animal study was approved by The Danish Animal Experiments Inspectorate (license no. 2015-15-0201-00523). The experiments were conducted on six female Danish Landrace pigs weighing about 40 kg (range 39.5–41.5 kg).

Infrarenal aortas from female sheep about 180 days old and weighing approximately 40 kg were obtained from a Danish slaughterhouse using semi-sterile conditions, and stored in sterile 0.9% NaCl solution with penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/mL, life technologies) at 4 °C until further processing.

All pigs used were from a specific-pathogen-free herd and evaluated as healthy by a veterinarian prior to inclusion. A special focus on infections diseases were given as this could alter the immunological process after the transplantation, and the donating sheep were similarly inspected and declared healthy by a veterinarian before being euthanized. Moreover, no vascular pathologies were observed during surgery or by histological evaluation of the removed infrarenal aortas”.

2.1. Graft preparation

The sheep aortic xenografts were treated in 0.5% SDS with 0.2 mg/mL DNase-I in Tris-EDTA buffer (TE buffer) at room temperature for 24 h with continuous shaking, and then rinsed with sterile 0.9% NaCl. The xenografts were stored in 0.9% NaCl with penicillin-streptomycin at 4 °C until transplantation.

2.2. AAA induction by sheep-to-pig decellularized infrarenal aortic xenotransplantation

The pigs were selected randomly from different litters for surgery by the animal keepers blinded from the kind of study and the selected decellularized sheep graft, which was selected 2–3 days before the transplantation by author MA.

The pigs were anaesthetized as previously described [10]. Preoperatively, a single dose of cefuroxime 1.5 g was administered intravenously.

Through a midline laparotomy the infrarenal aorta was exposed and dissected free from surrounding connective tissue. The lumbar artery closest to the renal arteries was preserved to prevent spinal cord ischaemia. (Fig. 1A). After 5000 IU of unfractionated heparin sodium was administered intravenously, the infrarenal aorta was clamped. An appropriate length of the infrarenal porcine aorta was removed (Fig. 1B) and replaced with the decellularized xenograft by end-to-end anastomosis using 5-0 Prolene sutures (Ethicon LLC, USA) (Fig. 1C and D). Transabdominal ultrasonography (USG) of the xenograft was performed in the longitudinal plane to measure the baseline anteroposterior systolic diameter (AP-0). Finally, the retroperitoneum and laparotomy were closed.

Fig. 1.

The transplantation process. (A) The porcine aorta dissected from the renal arteries (right side) to the trifurcation (left side). (B–D) Orthotopic replacement of the infrarenal porcine aorta by the sheep xenograft with end-to-end parachute anastomosis.

2.3. Postoperative care

Intramuscular injections of Streptocillin (Boehringer Ingelheim, Denmark) 1 mL/10 kg BW, flunixin 100 mg, and buprenorphine 1.8 mg was administered for the first three days as infection prophylaxis and pain relief, respectively.

2.4. Data collection

On postoperative day 8, 13, 22, 28, 35 and 47, the pigs were sedated in order to determine AP-diameter by USG performed by 4 observers. An AAA was defined as an infrarenal aortic AP-diameter of more than 1.5 times larger than AP-0. On postoperative day 47, blood samples were drawn in addition to USG measurements, thereafter the pigs were euthanized with a lethal dose of i.v. pentobarbital 300 mg/mL and the aortic xenografts including some of the porcine native aorta in both ends were harvested for histological and immunohistochemical analyses. Haematological parameters were analysed from the blood samples and compared with 12 healthy age- and sex-matched control pigs as previously described [8].

2.5. Histology

One middle and one distal section from each xenograft were fixed in 10% NBF and embedded in paraffin, along with both proximal and distal sections of the transplant area belonging to the porcine native aorta. The specimens were sliced in 5 μm sections and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (HE), Masson's trichrome (MT, Sigma), Miller's elastic counterstained with Van Gieson (EVG, Atom Scientific), and toluidine blue according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sigma). For immunohistochemistry, the specimens were stained with anti-α smooth muscle actin antibody (α-SMA) (Abcam, UK), and anti-mast cell tryptase antibody (Abcam, UK). All samples were compared to control sections from either the infrarenal sheep aorta prior to decellularization or the infrarenal porcine aorta removed during the transplantation procedure.

2.6. Sample size and statistical analyses

The sample size was based upon a power calculation based using paired t-test to be able detect a difference of 50% using the Kloster Study baseline data [8]. The paired two-sample t-test was used to compare the mean aortic AP-diameter at AP-0 with postoperative day 8, 13, 22, 28, 35 and 47. The unpaired two-sample t-test was used to compare haematology parameters between the experimental animals and controls. We carried out the analyses using Stata 13.0, StataCorp LP, USA. Results are presented as means ± SD, and p-values < 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

3. Results

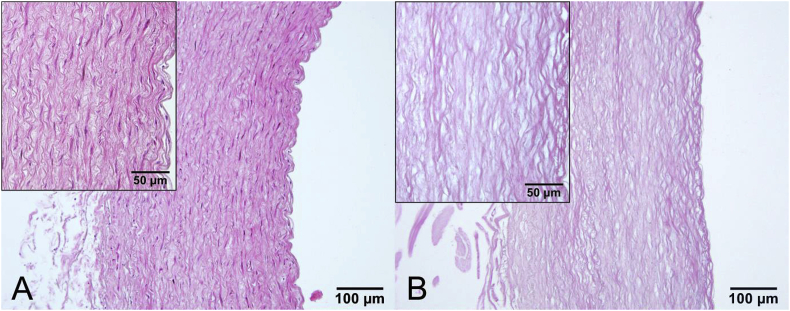

3.1. Decellularizing procedure

The effectiveness of the decellularization procedure using 0.5% SDS is shown in Fig. 2. Histologically, the xenografts were cell-free from all three layers of the arterial wall after SDS treatment. The elastic fibres remained mostly intact. No additive effects were seen after 48 h or with presence of DNase (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

The effect of decellularizing detergents on sheep aortas. No nuclei were detected in SDS decellularized xenografts (B) Non-decellularized controls (A). The specimens are stained with HE.

3.2. Macroscopic studies

All six pigs survived the 47-day study period. The mean preoperative weight was 40.2 ± 0.9 kg, and the mean aortic clamping time was 61.5 ± 10.3 min. The pigs recovered quickly after surgery, and no immediate postoperative complications were present. Normal appetite and weight gain was observed in all animals.

After 28 days, an abdominal hernia had developed in four of six pigs, but this did not affect the welfare of the animals. At postmortem examination two pigs had adhesions between the intestines and the abdominal wall, one pig had a hydroureter, and two pigs had a formation like a pseudoaneurysm or possibly a contained ruptured aneurysm. All pigs showed moderate to severe fibrosis surrounding the infrarenal aorta, as well as lymphatic formation encircling the area of the xenotransplantation.

All xenografts formed aneurysms with a significant diameter increase after 13 days compared to AP-0 and mean values of manifest AAA was present after 28 days according to our definition (55.42 ± 17.82%) (Table 1).The USG results demonstrated a progressive aneurysmal expansion that did not slow markedly at the end of the follow-up period day 47, although there was a large variation between the pigs (Fig. 3). At postoperative day 47, one pig had to be excluded from the results because of technical immeasurability, and one pig had to be scanned in the transverse plane in a lateral recumbent position.

Table 1.

Schematic presentation of mean weight, mean AP-diameter and mean increase over the course of the experiment.

| Day 0 | Day 8 | Day 13 | Day 22 | Day 28 | Day 35 | Day 47 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean weight ± SD (kg) | 40.2 ± 0.88 | 44.4 ± 1.11 | 47.3 ± 0.84 | 56.3 ± 1.14 | 59.7 ± 0.70 | 64.9 ± 0.73 | 75.5 ± 1.35 |

| Mean AP-diameter ± SD (mm) | 10.13 ± 0.64 | 10.50 ± 0.18 | 12.37 ± 1.47 | 14.22 ± 1.27 | 15.67 ± 1.02 | 17.27 ± 1.15 | 18.02 ± 1.89 |

| p-value | 0.25 | <0.05 | <0.005 | <0.0005 | <0.0005 | <0.002 | |

| Mean increase ± SD (%)a | 4.01 ± 7.77 | 23.03 ± 21.81 | 41.16 ± 19.31 | 55.42 ± 17.82 | 71.53 ± 22.40 | 80.98 ± 30.20 | |

| p-value | 0.26 | <0.05 | <0.005 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.005 |

Mean increase ± SD (%) with respect to AP-0.

Fig. 3.

Mean increase ± SD in AP-diameter. A progressive aneurysm expansion of the xenografts could be seen from baseline (AP-0) to postoperative day 47.

3.3. Haematology parameters

At postoperative day 47, plasma levels of myeloid and lymphoid cell line was significantly depressed in the pigs when compared to healthy controls (Table 2). They also displayed anaemia, leukopenia, and reticulocytopenia, while platelet counts were normal (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of haematology paratameters.

| Hgb (g/L) | RET (g/L) | PLT (g/L) | WBC (g/L) | Nent (g/L) | Lymph (g/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental animals | 94.7 ± 6.65 | 23.28 ± 7.06 | 398.17 ± 111.91 | 13.82 ± 0.82 | 4.15 ± 0.73 | 8.95 ± 1.10 |

| Controls | 116.8 ± 6.76 | 89.01 ± 37.84 | 355.50 ± 177.24 | 19.67 ± 3.37 | 6.12 ± 2.62 | 11.86 ± 2.11 |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.54 | <0.0001 | <0.03 | <0.002 |

Blood samples displaying depressed haematology parameters in the experimental animals compared to healthy controls.

Hgb = haemoglobin, RET = reticulocytes, PLT = platelet count, WBC = white blood cell count, Neut = neutrophils, Lymph = lymphocytes.

3.4. Morphological analyses of AAA

Histologic assessment of the decellularized xenografts before transplantation confirmed no nuclei in the specimen with HE staining. Based on Masson trichrome staining elastic fibers and collagen deposition appeared to be preserved. α-SMA staining confirmed that the xenografts were devoid of SMCs.

At removal, the arterial wall of the xenografts was macroscopically thickened. Nevertheless, light microscopic examination revealed largely no cell-invasion of the xenograft itself, whereas cells from the native porcine aorta had migrated to the inner and outer part of the xenograft and formed both massive neointimal hyperplasia and adventitial thickening when compared to control sheep aorta (Fig. 4). The thickening of tunica intima and adventitia consisted of SMCs, collagen deposition and inflammatory cells. Lymphocytes were arranged in germinal centers in tunica adventitia (Fig. 4B and D), while they were more spread in tunica intima along with granulocytes. Mast cell tryptase positive cells were mainly present in tunica adventitia, but some mast cells were also found along tunica intima of the xenograft (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Postmortem histological specimens. (A–B) Masson Trichrome staining of control sheep aorta (A) and postmortem aneurysm specimen (B). Collagen and reticular fibres are coloured blue, cytoplasm and SMCs are dark pink and nuclei are purple. Millers Verhoef van Gieson staining of control sheep aorta (C) and postmortem aneurysm specimen (D). Elastic fibres are purple/black, collagen is dark pink and cytoplasm and SMCs are yellow. Postmortem aneurysm specimens (B) and (D) show the xenograft (red arrow) surrounded by intimal and adventitial hyperplasia, and lymphocytes arranged in germinal centers in tunica adventitia (black arrows). Enlargement of D are shown in (E and F) displaying severe destruction of elastic fibers and thinning of tunica media of the decellarized xenograft. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Although barely any cells were present in the xenografts, structural remodelling was evident with prominent elastin destruction in tunica media, stretching of the elastic fibres and elastin rupture had occurred in all xenografts (Fig. 4E and F). In several of the specimens, inflammation and intramural haemorrhaging occurred in areas with elastin rupture, and some specimens had formed an intraluminal thrombus.

4. Discussion

This study has shown the feasibility of inducing autoimmune AAAs in pigs through decellularized aortic xenograft transplantation, with the presence of AAA already at day 28 (55.42 ± 17.82%) that continued to progress throughout the study period to a mean increase in AP-diameter of 80.98 ± 30.20% after 47 days. This substantial AP-diameter increase is far beyond what can be attributed to normal increase in body weight of the pigs as shown by the control pigs in our recent study by Kloster et al. [8] This study was performed at the same institution using pigs from the same herd and at the same age as in our study. Kloster et al. found an increased from 10.37 ± 0.19 mm to 11.33 ± 0.13 mm in the control pigs after 28 days, corresponding to an increase of 9.27 ± 1.37%, which is about a sixth of the increase in our experimental animals after 28 days.

The histological findings of the xenografts showed both destruction of tunica media and the elastic tissue, neovascularization, and infiltration of lymphocytes; all key histological aneurysm characteristics seen in humans [1], [3], [11], [12]. In addition, intraluminal mural thrombus development also occurred, just like in human AAAs [13], but not seen in many experimental animal models [5]. Inducing AAAs with a similar model has successfully been done in rodents [14], [15], but has never before been carried out in larger animals. Our model demonstrates a progressive aneurysmal expansion over time with no sign of halting; an important model feature in which previous chemically and mechanically induced porcine AAA models have failed [7], [9]. This model could be an alternative to the previously described pig AAA model by Kloster et al. [8] combining elastase infusion and stenotic banding to induce AAA with progressive expansion over time.

All animals survived the experimental period, and only minor complications were seen, none of which affected the animal's well-being. Four pigs developed an abdominal hernia. The hydroureter found in one of the pigs was probably a result of a partial ureteral stenosis as a complication to the surgical procedure.

The range of the AP-diameters varied greatly at postoperative day 47, which may be due to biological variation, variable immune responses, varying tension on the xenografts, the dimensional relationship between the porcine aortas and the xenografts, or stenosis of the anastomosis. Also, the variable USG results might have partly been a result of both intra- and interobserver variability considering four different people have performed the USG during the experimental period. This problem has previously been observed by Grondal et al. when systolic AP-diameter was measured in AAA patients [16]. They found an interobserver variability between two observers to be 1.52 mm, and an intraobserver variability of 0.94 mm. MRI or CT would most likely have provided more accurate estimates of the AP-diameter, but this was not feasible at our institution.

This model is applicable in many different animal species [6], although pigs are well suited because of their human resemblance in arterial morphology [6] the developed aneurysms imitate and share several characteristics with human AAAs. However, concerns have been raised about the xenograft models due to heterogenic formation of aneurysms and the lack of vessel rupture [17]. Nevertheless, our histological findings indicate an ongoing process which could lead to rupture, and actually two potential contained ruptures were observed. As for the study design, we note some limitations related to the small number of animals, the rather large SD in AP-diameter increase, and no strict randomization protocol. Furthermore, due to the feasibility purpose of the study a control group was not included and thus unblinded assessment of the aortic diameter, may have increased the risk of information bias. However, the mean changes in diameter of 8 mm is so marked that an unintended tendency to overestimate the diameter within the known intraobserver variability of ultrasound based measurements of aortic diameters of 2–3 mm makes it very unlikely, that such bias could have driven the significant finding.

Although the selection was not strictly randomized by numbers, selection bias seems unlikely. The same breeder, the same health check, and acclimatization procedure before surgery gave the pigs the same selection. Furthermore, the paired design takes the advantage of using itself just before transplantation as control excluding risk of confounding. Finally, we recognize that an extended follow-up period would be preferable, but the extensive weight gain in conventional pigs complicates long-term studies using this model.

5. Conclusion

We have shown that it is possible to induce autoimmune AAA with progressive expansion in pigs. This model may be useful in further investigations of the autoimmune aspect in aneurysm formation, and for preclinical testing of medical therapy directed against aneurysmal expansion or even reversal.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not necessary.

Animal study, The experimental animal study was approved by The Danish Animal Experiments Inspectorate, and performed in accordance with animal welfare legislations.

Sources of funding

Financial support was provided by Arvid Nilssons Fund. The funding source had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data or in the writing of this article.

Author contribution

All authors have more or less contributed to study design, data collection, data analysis and writing.

Contributed: We thank Brian Kloster for helping out with the USG. Furthermore, we thank the personnel at the Danish Centre for Food and Agriculture for animal care.

Conflicts of interest

None conflicts of interest.

Guarantor

Sara Schødt Riber and Jes Sanddal Lindholt take full responsibility for the work.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Not necessary, animal study.

Acknowledgements

We thank Brian Kloster for helping out with the USG. Furthermore, we thank the personnel at the Danish Centre for Food and Agriculture for animal care.

References

- 1.Kuivaniemi H. Update on abdominal aortic aneurysm research: from clinical to genetic studies. Sci. (Cairo) 2014;2014:564734. doi: 10.1155/2014/564734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jagadesham V.P., Scott D.J., Carding S.R. Abdominal aortic aneurysms: an autoimmune disease? Trends Mol. Med. 2008;14(12):522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindholt J.S., Shi G.P. Chronic inflammation, immune response, and infection in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2006;31(5):453–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu S. Aneurysmal lesions of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm contain clonally expanded T cells. J. Immunol. 2014;192(10):4897–4912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lysgaard Poulsen J., Stubbe J., Lindholt J.S. Animal models used to explore abdominal aortic aneurysms: a systematic review. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2016;52(4):487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trollope A. Animal models of abdominal aortic aneurysm and their role in furthering management of human disease. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2011;20(2):114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czerski A. Experimental methods of abdominal aortic aneurysm creation in swine as a large animal model. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2013;64(2):185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kloster B.O., Lund L., Lindholt J.S. Induction of continuous expanding infrarenal aortic aneurysms in a large porcine animal model. Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond) 2015;4(1):30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hynecek R.L. The creation of an infrarenal aneurysm within the native abdominal aorta of swine. Surgery. 2007;142(2):143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao H. Rifampicin-soaked silver polyester versus expanded polytetrafluoro-ethylene grafts for in situ replacement of infected grafts in a porcine randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2012;43(5):582–587. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hellenthal F.A. Histological features of human abdominal aortic aneurysm are not related to clinical characteristics. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2009;18(5):286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rouer M. Rapamycin limits the growth of established experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2014;47(5):493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michel J.B. Novel aspects of the pathogenesis of aneurysms of the abdominal aorta in humans. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011;90(1):18–27. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allaire E. Cell-free arterial grafts: morphologic characteristics of aortic isografts, allografts, and xenografts in rats. J. Vasc. Surg. 1994;19(3):446–456. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(94)70071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allaire E. The immunogenicity of the extracellular matrix in arterial xenografts. Surgery. 1997;122(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grondal N. The cardiac cycle is a major contributor to variability in size measurements of abdominal aortic aneurysms by ultrasound. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2012;43(1):30–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaragoza C. Animal models of cardiovascular diseases. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011;2011:497841. doi: 10.1155/2011/497841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]