Abstract

Background

Adrenal myelolipoma is an uncommon, benign, and hormonally non-functioning tumor that is composed of mature adipose tissue and normal hematopoietic tissue. Most cases to date are asymptomatic or have epigastric pain. Acute hemorrhage is the most dramatic manifestation of adrenal myelolipoma; though, it is a rare entity. Hemorrhagic shock due to adrenal myelolipoma, to our knowledge, was much less mentioned so far. Persistent bleeding and uncontrollable hypotension are considered to be absolute indications for immediate surgical operation.

Case presentation

Herein we presented a 32-year-old male patient with initial symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and epigastric pain progressing to altered consciousness and hypotension during ER course. Hemorrhagic shock due to a giant adrenal myelolipoma, R’t was diagnosed. Emergent exploratory laparotomy was executed, and en bloc excision of tumor was done.

Conclusion

Adrenal myelolipoma might be diagnosed as a adjunction to other main causes of illness; furthermore, adrenal myelolipoma could be asymptomatic in lifetime. In our case, however, manifesting as hemorrhage shock was challenging to diagnose step by step; instead, maintaining vital organs perfusion and identifying bleeding sources were to be done. Management of myelolipoma should be done on a case-to-case basis.

Background

Myelolipoma is a uncommon benign tumor of mesenchymal origin which consists of mature adipose tissue and normal hematopoietic cells. It occurs most often in adrenal gland [1] while extraadrenal (most often in the retroperitoneum) myelolipomas are also reported [2]. To date, most cases are asymptomatic or have epigastric pain. Acute hemorrhage is the most dramatic manifestation of adrenal myelolipoma; though, it is a rare entity. Hemorrhagic shock due to adrenal myelolipoma, to our knowledge, was far less mentioned so far. Myelolipoma accompanied by acute hemorrhage and calcification can complicate making the image-based diagnosis. Computed tomography frequently demonstrates large amounts of fat with areas of interspersed higher-attenuation tissue [3]. It is difficult to differentiate giant adrenal or extraadrenal myelolipomas from other fat-containing soft-tissue masses such as lipoma, liposarcoma, myolipoma, teratoma and an exophytic angioliposarcoma of the kidney [4].

Case presentation

A 32-year-old male patient has history of peptic ulcer disease under medication for a few months, and he presented to emergency department with 1-day duration of nausea, vomiting, and epigastric pain. Abdomen in ovoid shape, tenderness over RUQ of abdomen without rebounding pain, and normoactive bowel sound were found in physical exam. ECG showed sinus tachycardia. Initially, intravenous antacids was administered under tentative diagnosis of exacerbation of peptic ulcer disease; whereas, such illness persisted. On further inquiry, the abdominal pain was irrelevant to trauma, body posture, or food intake. Laboratory data were normal except leukocytosis with white blood cell count of 19,100/uL and neutrophil predominance: 91.2%. KUB showed a huge hypodense lesion over right upper region (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

KUB showed a hypodense lesion over right upper quodrant of abdomen

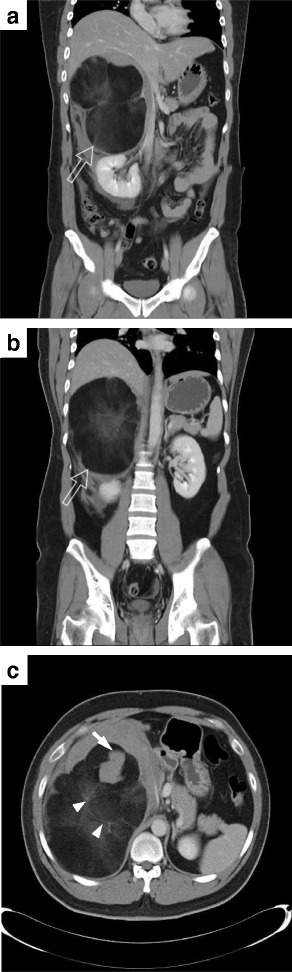

Sudden onset of altered consciousness with downhill of blood pressure was noted when awaiting the exam of CT(computerized tomography) of abdomen. He was resuscitated with intravenous fluid hydration and blood transfusion then. And CT of abdomen revealed a huge retroperitoneal majorly fat-content mass with ruptured hemorrhage (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

CT of abdomen with contrast showed a huge retroperitoneal majorly fat-content mass (open arrow) over right suprarenal (a & b) with ruptured hemorrhage (arrow), and interspersed with enhancing soft tissue components, as smoky appearance (arrowhead) (c)

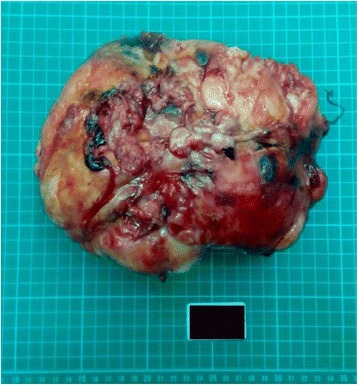

General surgery specialist performed emergent exploratory laparotomy immediately. En bloc excision of tumor was done. During operation, blood clots in abdominal cavity up to 1100 ml, and a huge retroperitoneal tumor with active bleeding, sized about 22x16x18 cm3 were found. Total blood loss was 3500 ml. The tumor weighed 1450 g (Fig. 3). Pathology microphotograph revealed numerous mature adipocytes surrounded by myeloid cells in adrenal gland indicating myelolipoma (Fig. 4) The patient led an uneventful postoperative hospital course.

Fig. 3.

Photograph of gross pathologic specimen shows encapsulated soft and yellow solid mass, measuring 22x16x18 cm3, weighed 1450 g

Fig. 4.

Microphotograph (a) (Hematoxylin & eosin, ×100) showed adrenal gland with intraparenchymal myelolipoma. b (Hematoxylin & eosin, ×200) showed zone fasciculata of adrenal gland, and zone reticulata was occupied by adipocytes. Numerous myeloid cells and immature red blood cell along with some megakaryocytes can be seen in (c) (Hematoxylin & eosin, ×400)

Discussion

Adrenal myelolipoma was first introduced in 1905 by Gierke, and following given the name myelolipoma by Oberling. It consists of lipoid and hematopoietic elements, and the reticulum is present only in the fatty areas [5]. The incidence of myelolipoma is 0.2% in the general population in reported autopsy studies. Acute hemorrhage is the most significant complication especially in large myelolipomas, and it can be manifested with local pain in the back, epigastrium, or flanks, accompanied with nausea, vomiting, hypotension and anemia [2].

It must be distinguished from extramedullary hematopoietic tumors, which are as below: 1.) more often multiple than solitary, 2.)frequently associated with splenomegaly and hepatomegaly, 3.)secondary to severe anemia (thalassemia, hereditary spherocytosis), various myeloproliferative diseases, myelosclerosis, and skeletal disorders [6].

In image study, computed tomography usually shows well-marginated, heterogeneous masses with macroscopic fat. Interestingly, a smoky appearance with attenuation values around 20-30HU could be found in some area of myelolipoma due to admixture of adipose and hematopoietic cells [2]. If non-invasive studies could not yield definite diagnosis, fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy should be considered [7–9]. Also in cases where expectant management is being considered, FNA can definitively rule out malignancy [9, 10].

Retroperitoneal hemorrhage due to spontaneous rupture of adrenal myelolipoma is very rare, and surgical resection is recommended [11–13]. Persistent bleeding with symptoms of hemorrhagic hypovolemia like refractory hypotension and altered consciousness are considered to be absolute indications for immediate surgical intervention [14]. The CT findings of the lesions with bleeding are not easy to identify. The most important is the difference in size with most bleeding lesions being greater than 10 cm. Sizes have been variably ranging from microscopic lesions to giant masses as big as 31 cm [15].

Though several theories have been proposed, the etiology of myelolipoma remains obscure. Theories include remnants of fetal bone marrow, embolism of bone marrow cells, and hyperplasia of heterotopic reticulum cells [16, 17]. Chang et al. described a case of adrenal myelolipoma with a translocation t(3;21)(q25;p11). A similar change, t(3;21)(q26;p11), is found in hematopoietic neoplasms, such as myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) indicating that myelolipoma is a derivative from misplaced hematopoietic cells [18]. Bishop et al. proposed a theory that X-chromosome inactivation in both fat and hematopoietic elements could be the clonal origin of myelolipoma [19]. The relationship between high-energy trauma and the development of adrenal myelolipoma has also been proposed [20], and significant changes in bone marrow hematopoiesis after severe trauma were shown in some studies [21, 22].

Management of myelolipoma should be done on a case-to-case basis. Patients with lesions <10 cm defined as myelolipoma on imaging procedures, should be observed closely for 1–2 years. If patient is asymptomatic and there is no tumor growth then the follow-up can be done at increasing time intervals, however the follow-up will be life-long because interval growth has been reported previously [23, 24].

Conclusion

For the symptoms and signs of adrenal myelolipoma are nonspecific, it might be diagnosed as a adjunction to other main causes of illness; furthermore, adrenal myelolipoma could be asymptomatic in lifetime. In our case, however, manifesting as hemorrhage shock was challenging to diagnose step by step; instead, maintaining vital organ perfusion and identifying bleeding sources were top priorities. Management of myelolipoma should be done on a case-to-case basis.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

HL and WC participated in the surgery of this case. HL and WC drafted the manuscript. SC, CH, YW, WK, CS, and PL read and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent form is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CT

Computerized tomography

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- FNA

Fine-needle aspiration

- IV

Intravenous

- KUB

Kidney, Ureter, Bladder

- RUQ

Right upper quadrant

Contributor Information

Hui-Pu Liu, Email: m1040970@gmail.com.

Wen-Yen Chang, Phone: +886-774-906-33, Email: wenyen85@yahoo.com.tw.

Shan-Tao Chien, Email: chienst@mail.802.org.tw.

Chin-Wen Hsu, Email: given_hsu@yahoo.com.tw.

Yu-Chiuan Wu, Email: ranger.wu1113@gmail.com.

Wen-Ching Kung, kung5437788@livemail.tw.

Chun-Min Su, Email: soajimmy@gmail.com.

Ping-Hung Liu, Email: dave700706@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Osborn M, et al. Adrenal myelolipoma - clinical, radiological and cytological findings: a case report. Cytopathology. 2002;13(4):242–246. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.2002.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenney PJ, et al. Myelolipoma: CT and pathologic features. Radiology. 1998;208(1):87–95. doi: 10.1148/radiology.208.1.9646797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin NY, et al. The differential imaging features of fat-containing tumors in the peritoneal cavity and retroperitoneum: the radiologic-pathologic correlation. Korean J Radiol. 2010;11(3):333–345. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2010.11.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar M, Duerinckx AJ. Bilateral extraadrenal perirenal myelolipomas: an imaging challenge. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(3):833–836. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.3.1830833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hakim A, Rozeik C. Adrenal and extra-adrenal myelolipomas - a comparative case report. J Radiol Case Rep. 2014;8(1):1–12. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v8i1.1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Remstein ED, Kurtin PJ, Nascimento AG. Sclerosing extramedullary hematopoietic tumor in chronic myeloproliferative disorders. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(1):51–55. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.deBlois GG, DeMay RM. Adrenal myelolipoma diagnosis by computed-tomography-guided fine-needle aspiration. A case report. Cancer. 1985;55(4):848–850. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850215)55:4<848::aid-cncr2820550423>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galli L, Gaboardi F. Adrenal myelolipoma: report of diagnosis by fine needle aspiration. J Urol. 1986;136(3):655–657. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaboardi F, et al. Adrenal incidentalomas: what is the role of fine needle biopsy? Int Urol Nephrol. 1991;23(3):197–207. doi: 10.1007/BF02550412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wadih GE, Nance KV, Silverman JF. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of the adrenal gland. Fifty biopsies in 48 patients. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1992;116(8):841–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldman HB, Howard RC, Patterson AL. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage from a giant adrenal myelolipoma. J Urol. 1996;155(2):639. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moran, R.E., et al., Genitourinary case of the day. Giant adrenal myelolipoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 1996. 167(1): p. 246, 248. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Hoeffel C. Rupture and growth of adrenal myelolipoma in two patients. Br J Radiol. 1998;71(846):693. doi: 10.1259/bjr.71.846.9849399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amano T, et al. Retroperitoneal hemorrhage due to spontaneous rupture of adrenal myelolipoma. Int J Urol. 1999;6(11):585–588. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.1999.611109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akamatsu H, et al. Giant adrenal myelolipoma: report of a case. Surg Today. 2004;34(3):283–285. doi: 10.1007/s00595-003-2682-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao B, et al. Mediastinal myelolipoma. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2002;10(2):189–190. doi: 10.1177/021849230201000227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karam AR, et al. Multifocal extra-adrenal myelolipoma arising in the greater omentum. J Radiol Case Rep. 2009;3(11):20–23. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v3i11.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang KC, et al. Adrenal myelolipoma with translocation (3;21)(q25;p11) Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2002;134(1):77–80. doi: 10.1016/S0165-4608(01)00592-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bishop E, et al. Adrenal myelolipomas show nonrandom X-chromosome inactivation in hematopoietic elements and fat: support for a clonal origin of myelolipomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(7):838–843. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000202044.05333.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zorgdrager M, et al. Giant adrenal myelolipoma: when trauma and oncology collide. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Livingston DH, et al. Bone marrow failure following severe injury in humans. Ann Surg. 2003;238(5):748–753. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094441.38807.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Francis WR, Bodger OG, Pallister I. Altered leucocyte progenitor profile in human bone marrow from patients with major trauma during the recovery phase. Br J Surg. 2012;99(11):1591–1599. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han M, et al. The natural history and treatment of adrenal myelolipoma. J Urol. 1997;157(4):1213–1216. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)64926-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhurgri A, Bhurgri Y, Khwaja IA. Adrenal myololipoma--a case report. J Pak Med Assoc. 2001;51(2):85–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.