Abstract

For broad protection against infection by viruses such as influenza or HIV, vaccines should elicit antibodies that bind conserved viral epitopes, such as the receptor-binding site (RBS). RBS-directed antibodies have been described for both HIV1–3 and influenza virus4–8, and the design of immunogens to elicit them is a goal of vaccine research in both fields. Residues in the RBS of influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) determine a preference for the avian or human receptor, α -2,3-linked sialic acid and α -2,6-linked sialic acid, respectively9,10. Transmission of an avian-origin virus between humans generally requires one or more mutations in the sequences encoding the influenza virus RBS to change the preferred receptor from avian to human9,11,12, but passage of a human-derived vaccine candidate in chicken eggs can select for reversion to avian receptor preference13–15. For example, the X-181 strain of the 2009 new pandemic H1N1 influenza virus, derived from the A/California/07/2009 isolate and used in essentially all vaccines since 2009, has arginine at position 226, a residue known to confer preference for an α -2,3 linkage in H1 subtype viruses13,14; the wild-type A/California/07/2009 isolate, like most circulating human H1N1 viruses, has glutamine at position 226. We describe, from three different individuals, RBS-directed antibodies that recognize the avian-adapted H1 strain in current influenza vaccines but not the circulating new pandemic 2009 virus; Arg226 in the vaccine-strain RBS accounts for the restriction. The polyclonal sera of the three donors also reflect this preference. Therefore, when vaccines produced from strains that are never passaged in avian cells become widely available, they may prove more capable of eliciting RBS-directed, broadly neutralizing antibodies than those produced from egg-adapted viruses, extending the established benefits of current seasonal influenza immunizations.

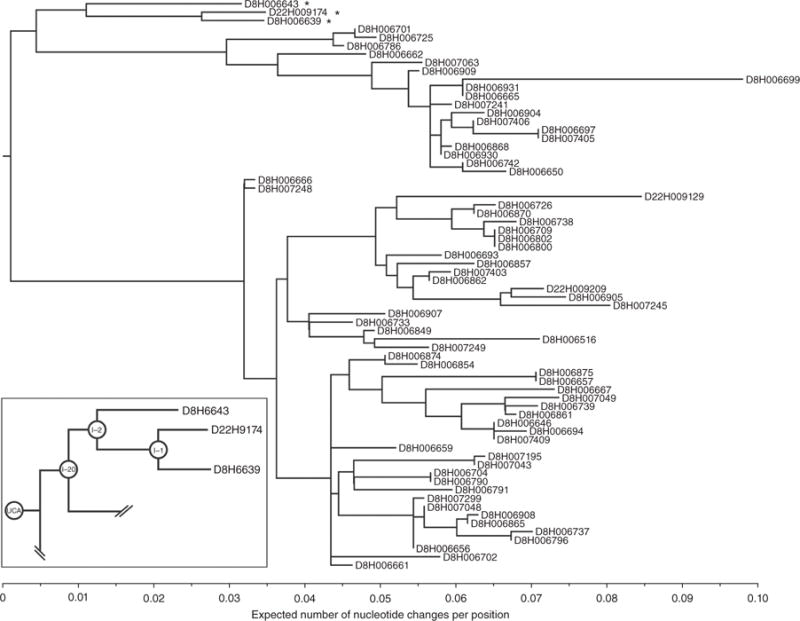

We studied a large B cell clonal lineage derived from single-cell sorting and paired-chain sequencing of plasmablasts from a participant (Siena patient 7) in a clinical trial of a pdm2009 vaccine produced at Novartis Vaccines16. Of the 217 paired-chain, HA-reactive antibody sequences from cells that were drawn 8 d after vaccination17, phylogenic analysis18,19 assigned 64 to a single clonal lineage, CL6515 (Fig. 1). Subsequent analysis of day 22, antigen-specific B cells yielded three additional lineage members (Fig. 1). We examined the course of affinity maturation leading to antibody (Ab) 6639, in the branch with common ancestor I-2 (Fig. 1, inset). The three antibodies in this branch, Ab6639 and Ab6643 from day 8 and Ab9174 from day 22, differ from I-2 by 11, 6 and 12 amino acid residues, respectively, and by 15, 10 and 16 residues from the unmutated common ancestor (UCA) of the lineage, as inferred from the phylogeny18,19. The variable (V)-domain sequences of the antibodies that we studied are in Supplementary Figure 1a, and the complementarity-determining region (CDR)-H3 sequences for a larger set from CL6515 are in Supplementary Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

B cell clonal lineage CL6515 from Siena patient 7. The tree was derived, using Clonalyst18,19, from single-cell, paired heavy- and light-chain sequences. The genes encoding the variable domains are: IGHV5-51, IGHJ6*02, IGKV3-20, IGKJ1*01. The antibodies are designated by heavy-chain sequence number, preceded by ‘D8’ or ‘D22’ for cells obtained either 8 or 22 d after vaccination, respectively. Inset: the subtree that includes Ab6639. Antibodies defining that subtree are marked with asterisks in the main figure.

Ab6639 neutralized the egg-adapted vaccine strain, X-181, with a concentration of half-maximal inhibition (IC50) of ~0.007 μg/ml, but it neutralized the wild-type pdm2009 strain with an IC50 ~3.6 μg/ml, thus showing nearly three orders of magnitude less potency for the circulating virus (Table 1). This vaccine-strain specificity was found throughout the CL6515 lineage (unpublished data; see legend for Supplementary Fig. 1b). Three mutations in HA (Asn133Asp, Lys212Thr and Gln226Arg) occurred during the generation of the X-181 vaccine virus (Supplementary Fig. 1c). The antigen-binding fragment (Fab) of antibody 6639 bound the X-181 HA with a Kd ~ 3 μM, but it had no detectable binding to the HA of the wild-type isolate (Table 1 and Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). We could restore affinity to the latter by mutating Gln226 to arginine (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3). This result shows that Arg226 in the HA RBS is crucial for Ab6639 binding to pdm2009. Arg226 is not the sole determinant of binding, however, as Fab6639 failed to bind the HA of the vaccine strain derived from A/Solomon Islands/03/2006, an H1N1 isolate that preceded the emergence of pdm2009 in humans; similarly to X-181, the vaccine strain from that isolate acquired arginine at position 226 (Supplementary Fig. 1c).

Table 1.

HA binding KD (10−6 M) and neutralization IC50 (μg/ml)

| CL6515 (Fab) (Siena cohort) |

A/California/07/2009 (wild-type)

|

X-181

|

Q226R

|

A/USSR/92/1977

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd | IC50 | Kd | IC50 | Kd | Kd | IC50 | |

| UCA | >50 | >25 | >50 | 12 | – | 15 ± 2.8 | >25 |

| I-2 | – | 6.5 | 8.9 ± 2.7 | 0.028 | – | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 0.012 |

| I-1 | – | 1.2 | 9.7 ± 3.1 | 0.009 | – | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 0.011 |

| Ab6639 | >50 | 3.6 | 3.6 ± 1.4 | 0.007 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 0.031 |

| Ab9174 | – | 1.2 | – | 0.001 | – | – | 0.028 |

| Donor 1 (Fab) (2011–12 cohort) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| H1–2 | >100 | >25 | 0.83 ± 0.24 | 0.01 | 0.31 ± 0.06 | – | – |

| H1–12 | >100 | >25 | 1.7 ± 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | – | – |

| H1–53 | >100 | >25 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 0.8 | 12.6 ± 1.1 | – | – |

| Donor 2 (Fab) (2011–12 cohort) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| H1–45 | – | 8 | – | 0.02 | – | – | – |

X-181, HA of the vaccine strain derived from A/California/07/2009; Q226R, HA of A/California/07/2009 with Gln226 mutated to arginine (but no change in the other two residues mutated in X-181).

We also found a preference for X-181 in the hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) strength and neutralization titer of polyclonal sera from Siena patient 7. For example, at day 22, the HAI titer for X-181 was fourfold higher than it was for wild-type A/California/07/2009; the neutralization titers had essentially the same ratio (Supplementary Table 1). The vaccine strain preference was still evident in serum drawn at day 202. The vaccine-induced titers for the wild-type strain were also substantial; at least part of this reactivity was probably due to antibodies recognizing epitopes other than the RBS.

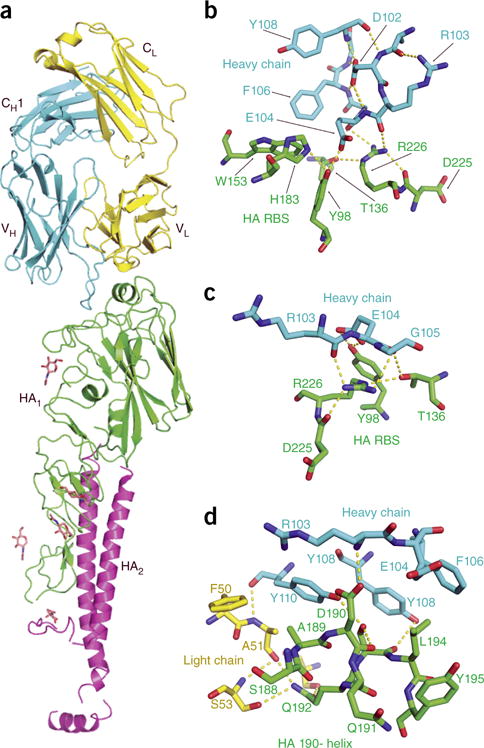

We crystallized the monomeric X-181 HA (Supplementary Fig. 4) in complex with Fab6639 and determined its structure (Fig. 2). As predicted by the effect of the Gln226Arg mutation, Ab6639 contacts the RBS. The two complexes in the asymmetric unit were nearly identical but allowed for two independent views of the molecular interactions between the Fab and HA. Ab6639 engages the HA RBS primarily through its CDR-H3 loop, with additional hydrogen bonds with CDR-L2 and CDR-L3. Although a glutamic acid residue (Glu104) on CDR-H3 projects into the sialic acid pocket, it does not interact with Thr136, as do the aspartic acid residues on those heavy chains that more closely mimic receptor contacts7,8. It instead receives hydrogen bonds from His183 and from the phenolic oxygen of Tyr98, the end point of a conserved chain of hydrogen bonds lining the base of the receptor site from Trp153 to Tyr195 to His183 to Tyr98 (ref. 20) (Fig. 2b,c). A van der Waals contact with Leu194 further fixes its position (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

Structure of Fab 6639 bound with uncleaved HA (HA0) of the X-181 vaccine strain. (a) Ribbon representation of the structure. The HA trimer dissociates after removal of the C-terminal foldon tag, causing part of the stem of the HA0 monomer to become disordered; the complex that crystallizes contains one Fab bound with one HA0 monomer. CDR-H3 of the Fab projects into the RBS on the ‘head’ of the HA molecule. Fab heavy chain is in blue; Fab light chain is in yellow; the HA1 (receptor-binding) part of the HA0 chain is in green; and the HA2 (fusogenic) part is in magenta. The initial N-acetylglucosamine of five glycans, shown in stick representation, were visible in the density map. (b) Contacts between residues at the tip of CDR-H3 and residues in the RBS, showing the role of Arg226. The view is roughly 90° (clockwise about a vertical axis) from the view in a. Hydrogen bonds are yellow dashed lines. The hydrogen bonds that buttress the Arg226 side chain position it to donate two hydrogen bonds to carbonyls on the CDR-H3 loop of the Fab. (c) View 180° from the view in b. (d) Contacts with residues in the 190-helix. View direction is from ‘below’ in a.

An adjacent polar network centers on Arg226, the critical mutated residue (Fig. 2b,c). Hydrogen bonds with Oγ of Thr136 and the main-chain carbonyl of Asp225, as well as stacking of its aliphatic segment on Tyr98, buttress the Arg226 side chain, positioning it to donate hydrogen bonds to the carbonyl group of heavy-chain residue 103. The guanidinium group stacks on the peptide bond between heavy-chain residues 104 and 105; its positive charge may contribute to stabilization of the carboxylate of Glu103, which loses solvent accessibility when the antibody binds HA.

The various contacts just described can explain the specificity of this antibody for the egg-adapted strain and its low affinity for pdm2009. Gln226 would lack most or all of the interactions with CDR-H3 that seem to contribute to binding; model building does not suggest any compensatory contacts. Interactions with the 190-helix (Fig. 2d) can account for the failure to bind the A/Solomon Islands/03/2006 HA, even with arginine at position 226. HAs from other egg-adapted seasonal strains with Arg226 might, however, have detectable affinity for Ab6639 or a precursor in the lineage, as H1 isolates show considerable variability of the contacting 190-helix residues.

The phylogenetic tree of CL6515 indicates that the day 8 plasma cells correspond to a recall response. The extent of somatic hypermutation (SHM) for many of the day 8 antibodies in the ‘lower’ part of the tree in Figure 1 is about 7%, larger than estimates for the outcome of a primary response (generally considered to be no greater than about 2.5%; refs. 21–23); the subtree from which Ab6639 arose has about 3% SHM. The day 22 antibodies do not have a greater extent of SHM than that of their close siblings in the lineage (Fig. 1). We conclude, as also inferred from kinetics of the serological response16, that despite no prior exposure of the vaccine recipient to the pdm2009 HA, immunization with X-181 elicited a recall from memory— presumably of a previous exposure to seasonal HAs (either by infection or vaccination).

CL6515 might have arisen from vaccination with a previous, egg-adapted HA or from infection by a much earlier H1 strain. We examined a series of historical isolates to determine whether the inferred UCA of the lineage has detectable affinity for the head of any of the corresponding HAs. The UCA bound the HA of A/USSR/92/1977 (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 5); this strain, which reintroduced H1N1 viruses into human circulation after displacement by H2N2 in 1957 (refs. 24–26), has a glutamine at HA position 226. Ab6639 and Ab9174 also neutralized A/USSR/92/1977, although the UCA of the lineage, which bound less tightly than its affinity-matured progeny, did not (Table 1). Siena patient 7 was born in 1975; the 1977 virus or a related strain is the first H1 subtype to which that person could have been exposed.

We have previously shown that the UCAs of six different, RBS-directed antibody lineages from a participant in a 2008 US study bind relatively strongly to the HAs of the seasonal strains that were circulating when that person was an infant6. Binding of the UCA of CL6515 to the 1977 virus suggests that, in this case as well, an initial exposure produced memory recall in response to vaccination many years later. The result further suggests that a vaccine with Arg226 can subvert a response to a Gln226-containing circulating virus, by inducing affinity maturation that generates selectivity for the vaccine strain. Previous vaccination of the donor with seasonal vaccines that included an H1N1 HA with Arg226 might already have selected for the switch in specificity.

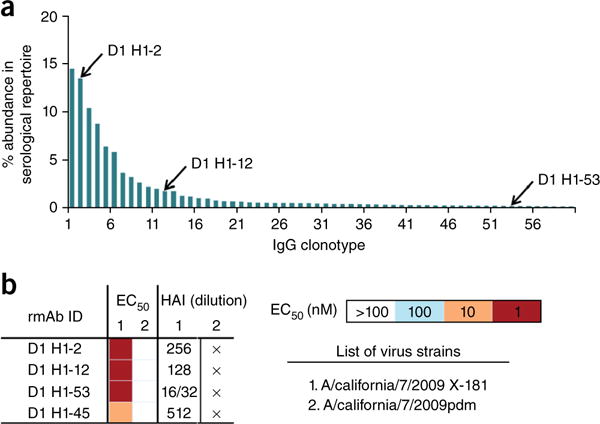

We could extend the conclusions just described by analyzing antibodies specific for the X-181 vaccine strain found in studies of the serum-antibody repertoires of two US donors who had received a 2011–2012 trivalent vaccine (ref. 27 and Online Methods). Figure 3a shows the relative abundances of anti-H1 IgG CDR-H3 clonotypes detected in the day 28 serum of donor 1 following enrichment by affinity chromatography with an immobilized H1 vaccine component (ref. 27 and Online Methods). We selected at random three antibodies representing clones with high (D1 H1–2), medium (D1 H1–12) and low (D1 H1–53) abundance in the serological repertoire, respectively. We found that all three were specific for X-181 (Fig. 3b); we did not detect any of the three in our analysis of the pre-immunization samples. All three antibodies bound HA from X-181, which has arginine at position 226, but none bound the circulating-strain HA, which has glutamine at 226 (Table 1). Their neutralization profiles were also X-181 specific (Table 1). Another antibody, D2 H1–45, from a second donor (one of three antibodies selected for expression at random from that donor’s serum antibody repertoire; the other two had a different epitope specificity) also potently neutralized the X-181 virus and neutralized the circulating strain only weakly (Table 1). Table 1 shows the affinities of Fabs from the donor 1 antibodies for the X-181 and wild-type pdm2009 HAs and for the latter with a Gln226Arg mutation. The pattern of affinities matches that of Fab6639, and the sensitivity to the mutation at position 226 shows that the antibodies are RBS directed. The aligned sequences of the four heavy- and light-chain variable domains are in Supplementary Figure 6. The prevalence of antibodies specific for X-181 suggests that they may be a major component of the serum response to vaccination. Indeed, the polyclonal serum response at days 7 and 28, as monitored by HAI assays, was also stronger for X-181 than for wild-type pdm2009 (Supplementary Table 1). The extent of SHM (overall nucleotide changes of 5.8%, 3.8%, 4.5% and 4.5%, respectively, in the heavy-chain variable domain) indicates that these antibodies, like Ab6639, are part of a secondary response. Neither donor reported a history of pdm2009 exposure, and the antibodies we have studied, similarly to the lineage from the Siena participant16, probably illustrate ‘redirecting’ of a previous, seasonal response.

Figure 3.

Serum antibody repertoire and analysis of three antibodies from donor 1 of the 2011–12 cohort. (a) Abundance of individual antibody clonotypes in the anti-H1 repertoire, as determined from mass spectrometric analysis of serum 28 d after vaccination. Each bar denotes a unique antibody clonotype, and the three antibodies analyzed represent high-, moderate- and low-abundance clonotypes (second, twelfth, and fifty-third ranked, respectively). (b) Characterization of the three antibodies with HA from X-181 and pdm2009. HAI, hemagglutination inhibition assayed with the virus strains listed; cross (×) indicates no activity even at the lowest dilution. IC50 values were determined by ELISA with the HAs from the listed strains.

The most notable conclusion from this study is that many vaccine-elicited antibodies fail to bind or neutralize the corresponding circulating strain, because of their specificity for a mutation that adapted the vaccine strain for growth in chicken eggs. Of the three altered amino acid residues in HA of the X-181 egg-grown vaccine strain, only Arg226, a well-documented mutational adaptation to the avian receptor, affected binding of the antibodies we have characterized. Our finding reinforces concerns, raised by early comparisons of egg-grown and mammalian-cell-grown viruses13, that general use of egg-adapted viruses for vaccine production might misdirect part of the response. Even influenza vaccines currently produced in mammalian cell culture mostly derive from candidate vaccine viruses that were propagated in eggs.

A second conclusion is that the very large B cell clonal lineage from the Siena cohort participant, CL6515, and the serum antibodies from the US 2011–12 cohort, come from recall responses, rather than from primary responses to the pdm2009 vaccine. The UCA of CL6515 binds the 1977 USSR strain that reintroduced H1N1 viruses into circulation. That virus, or a related strain from the late 1970s or early 1980s, is the first H1N1 virus that the participant would have encountered as an infection.

RBS-directed antibodies can afford broad serological responses to H1N1 strains7. Because of possible changes in the RBS when potential vaccine strains are passaged in eggs, conventional influenza virus vaccines may elicit such antibodies less effectively than those that are produced, from initial virus isolation to antigen production, exclusively in mammalian cells.

METHODS

Methods, including statements of data availability and any associated accession codes and references are available in the online version of the paper.

ONLINE METHODS

Samples

Plasmacytes were sorted from an individual who was administered an experimental vaccine (developed by Novartis16) for pandemic 2009 H1N1; blood was drawn before vaccination, and at days 8, 22 and 202 after vaccination, immediately followed by isolation and cryopreservation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki; the protocol and all documents related to the study were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the ‘Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese’ (see ref. 16 for a complete description of procedures and for statement of Ethics Committee approval and informed consent). Subsequent steps were carried out at the Duke Human Vaccine Institute, following published protocols17. PBMCs were sorted to isolate plasmablasts (from the sample taken 8 d after immunization) and antigen-specific B cells (from the remaining samples). Gating for plasmablasts was as described28. Antigen-specific sorting was performed as described29 using X-181 protein aliquots separately labeled with two fluorochrome colors; antigen-specific memory B cells were sorted as viable singlet events gated as CD3−CD14−CD16−CD235a−CD19+ surface IgD− that were positive for binding both differentially labeled X-181 proteins (sample plots for antigen-specific sorting are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7). Plasmablast sorting yielded 415 paired-chain sequences, of which 76 bound with the HA in the immunogen. The vaccine strain, X181, had acquired three mutations in the HA ectodomain, N133D, K212T and Q226R, during passage through chicken eggs. Blood was drawn 8 d post vaccination, immediately followed by isolation and cryopreservation of PBMCs. Subsequent steps were carried out at the Duke Human Vaccine Institute, following published protocols17.

X-181-specific antibodies were identified from the sera of two donors following vaccination with the 2011–12 trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (Fluzone; Sanofi-Pasteur) as described29. Briefly, serum antibodies were affinity-purified on immobilized, inactivated-virus vaccine protein (H1 component of the vaccine), and CDR-H3 peptides were identified and quantified by LC–MS/MS as described previously30. Paired VH:VL gene repertoire databases from peripheral B cells of the same individuals were determined by single-cell emulsion overlap extension PCR and NextGen sequencing31 and were used to determine the sequences of the full-length antibodies that contained the proteomically detected the CDR-H3 peptides.

Cloning, expression and purification of Fabs

Variable and constant domains of the heavy and light chains of Fab regions of monoclonal antibodies were amplified from expression vector pcDNA 3.1 and cloned into the modified pVRC8400 expression vector, between a tissue plasminogen activation signal sequence and a C-terminal noncleavable 6× histidine (6×His) tag. Fabs were produced by transient transfection of 293T cells that have been adapted for suspension culture, using polyethylenimine (PEI) as the transfection reagent. The supernatant was harvested 6 d after transfection and clarified from cellular debris by centrifugation at 4,200 r.p.m. for 20 min. Fabs were purified using Ni–NTA agarose followed by gel filtration chromatography on a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare). Purified Fabs were concentrated to >15 mg/ml and stored at 4 °C until needed.

Cloning, expression and purification of hemagglutinin

Codon-optimized cDNA—encoding the ectodomain of pdm2009 HA, containing a human rhinovirus protease 3C cleavage site, a trimerization domain from T4 fibritin (foldon) and a C-terminal 6×His tag, and synthesized by GenScript—was sub-cloned into a pFastBac vector modified for ligation-independent cloning (LIC). The construct encoding HA from strain X181 was produced by site-directed mutagenesis of three residues in the wild-type plasmid. Trichoplusia ni (Hi5) cells were infected with a high-titer P3 stock of recombinant baculovirus. 72 h after infection, the supernatant was harvested, clarified by centrifugation and loaded onto Ni–NTA sepharose resin (Qiagen). The bound protein was washed with 20 column volumes of PBS supplemented with 20 mM imidazole before elution with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 500 mM imidazole. The eluted protein was dialyzed into PBS and incubated overnight with PreScission protease at a ratio of 1 unit to 100 μg of HA to remove the foldon trimerization and 6×His tags. HA was repurified by orthogonal Ni–NTA agarose chromatography followed by gel-filtration chromatography using a Superdex 200 column. The purified protein was concentrated to >10 mg/ml and stored at 4 °C until needed. Production of globular ‘head’ versions of HA is described elsewhere32. The purified HA0 was not further processed to HA1 and HA2.

Hemagglutination-inhibition assay

Hemagglutination and HAI assays were performed according to standard World Health Organization methods33. Four HA units (HAU) of H1N1 were tested using a 0.5% suspension of turkey red blood cells in 1× PBS. HAI titers were reciprocals of the highest dilutions of sera that inhibited hemagglutination. Post infection human plasma was treated with receptor-destroying enzyme (II) from Denka Seiken Co.

Microneutralization assay

Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were cultured in suspension in a proprietary medium with shaking at 37 °C. Prior to the assay, cells were pelleted and resuspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Lonza, 12-604F) with 10% FBS and penicillin–streptomycin (Lonza, 17-602E). A half-area microtiter plate (Corning, 3696) was seeded with 2 × 104 cells and incubated for 6 h at 37 °C. Antibodies were normalized to a concentration of 100 μg/ml in DPBS (Lonza, 17-512F). Fourfold serial dilutions of the antibodies were performed in DMEM with 1% bovine serum albumin (Rockland, BSA-30) and penicillin–streptomycin starting at a concentration of 25 μg/ml. Antibody dilutions were incubated with virus for 2 h at 37 °C and added to cells after replacing the medium with DMEM–BSA–penicillin–streptomycin. After overnight incubation at 37 °C, the supernatant was aspirated, and the cells were fixed with a 1:1 mixture of acetone (Sigma, 320110) and methanol (Sigma, 179957) for 1 h at −20 °C. Plates were washed with DPBS with 0.05% Tween-20 (Sigma, P1379), blocked with DPBS with 2% BSA, and stained using anti–influenza A nucleoprotein (Millipore, MAB8251) followed by Alexa-Fluor-488-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG (H+L) Ab (Invitrogen, A11001). Stained foci were counted with an ImmunoSpot Analyzer (CTL). Results were summarized as the ratio (×100) of infected cells present in a given sample to the average in the control wells without antibody for that plate (% infectivity). Table 1 reports the concentration of antibody at which the percentage of infectivity fell to 50. All neutralization assays were carried out with a minimum of three replicates.

Crystallization, data collection and structure determination for Fabs of Ab6652 and the UCA of CL6515

The heavy chain of Ab6652 is identical to those of antibodies 6709, 6800 and 6802; an ambiguity in the paired light-chain sequence caused Ab6652 to be omitted from Figure 1. Ab6652 probably represents its three immediate siblings quite accurately. We include the structure determination here, because it was used for molecular replacement (MR) in determining the structure of the X-181:Fab6639 complex. Fab6652 crystallized in space group P21 from 0.1 M sodium citrate pH 5.6, 20% PEG 4000, 20% isopropanol and 10% glycerol as a cryoprotectant. We determined the structure by MR with Phaser using a hybrid Fab from PDB 4HP0 and 4FQL. Statistics for the diffraction intensities and model refinement are in Supplementary Table 2. The UCA of the lineage crystallized in space group P212121 from 0.5 M NaCl, 0.05 M Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 22% PEG 4000 and 20% glycerol as a cryoprotectant. We determined the structure by MR with the Fab6652 coordinates; statistics for the diffraction intensities and model refinement are in Supplementary Table 2.

Crystallization of X-181:Fab6639 complex

We incubated Fab of Ab6639 with X-181 HA ectodomain at a molar ratio of 1.3:1, separated the complexes from excess Fab by gel filtration and concentrated the protein to 13 mg/ml. Crystals of the complex grew in 3 d, by hanging-drop vapor diffusion at 20 °C, from a 1:1 mixture of the concentrated complex and reservoir solution containing 12% (wt/vol) PEG 8000, 10% (wt/vol) 2-methyl-2,4-pentancediol and 25 mM KH2PO4. The crystals were cryoprotected by soaking for 5 s in a reservoir solution augmented with 25% glycerol, harvested into loops and flashed-cooled by plunging into liquid N2.

Data collection and structure determination

Diffraction data were collected at 100 °K on NECAT 24-ID-C at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory (Argonne, IL). Diffraction images were indexed, integrated and scaled using XDS34. Models of pdm2009 (PDB 4EDA), separated into head and stem, and Fab6652 were used as MR probes in PHASER35. Density modification with DM36 and model rebuilding to fit the modified map with O37 yielded coordinates that we refined using BUSTER (Global Phasing Ltd., Cambridge, UK) with twofold noncrystallographic symmetry (NCS) restraints and translation-libration-screw (TLS) parameterization of molecular motion. We used PyMOL (Schrödinger, New York, NY) to align structures and generate figures. Statistics for data and refinement are in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

Biolayer interferometry experiments and affinity analysis

We measured affinities by biolayer interferometry (BLI) on a QKe instrument (ForteBIO, Pall Corporation). We used 96-well black, half-area microplates (Greiner Bio-one), immobilized purified 6×His-tagged Fab on a Ni–NTA biosensor, and plunged each biosensor into a well containing 150 μl of serial dilutions of untagged purified HA ectodomain or the globular ‘head’ construct until saturation. All experiments were done with controls using no Fab or no HA. We obtained equilibrium dissociation constants by fitting saturation data with a nonlinear least-squares regression to BLI = Bmax × [HA]/(Kd + [HA]) in Prism (version 6.0d, GraphPad), where Bmax is BLI signal at maximal binding in nanometers, Kd is the dissociation constant, and [HA] is the concentration of HA ectodomain. Traces and fits with binding curves are in Supplementary Figures 2, 3 and 5.

Statistical analysis

Statistics for crystallographic data and refinement for Figure 2 are in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. In Table 1, Kd measurements were carried out by fitting binding curves from eight concentrations, for CL6515 Fabs, as shown in Supplementary Figures 2, 3 and 5, and from six concentrations for Donor 1 Fabs; s.d. are from the nonlinear least-squares fit described in the subsection on BLI experiments and affinity analysis. In Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1, microneutralization assays were carried out with at least four replicates in at least two separate experiments.

Data availability

Diffraction data are included in the Protein Data Bank depositions. Antibody sequences were deposited in GenBank. Plasmids for protein expression are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank C.L. Dekker (Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University) and S.R. Quake (Department of Bioengineering and Applied Physics, Stanford University) for the serum samples analyzed in Supplementary Table 1, and the staff members at Advanced Photon Source sector 24 (NE-CAT) and Advanced Light Source beamline 8.2.2 for assistance with X-ray data collection. The NE-CAT beamlines are funded by NIH grant P41 GM103403, and the APS is operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. The research in the authors’ laboratories was supported by NIH grants P01 AI089618 (S.C.H.) and 5U19 AI057234 (G.G.), DTRA contract HDTRA 1-12-C-0105 (G.G.), and the Clayton Foundation for Research (G.G.). S.C.H. is an Investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Accession codes. Protein Data Bank (PDB): coordinates and diffraction data have been deposited under accession codes 5IBL (for X-181 with Fab6639), 5IBT (UCA) and 5IBU (Fab 6652). GenBank: gene sequences encoding the antibodies described in Supplementary Figure 1 have been deposited under accession codes KU948663 through KU948678.

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.D.R., S.M.S., J.L., J.F., G.B., K.T.D., M.J.E., P.S. and M.A.M. performed experiments and analyzed data; E.C.S., G.G., T.B.K., H.-X.L., A.G.S. and S.C.H. analyzed data; and D.D.R., S.M.S., J.L., J.F., G.B., E.C.S., P.R.D., G.D.G., O.F., T.H.K., G.C.I., G.G., T.B.K., B.F.H., M.A.M., H.-X.L., A.G.S. and S.C.H. wrote, edited or commented on the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare competing financial interests: details are available in the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Wu X, et al. Rational design of envelope identifies broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to HIV-1. Science. 2010;329:856–861. doi: 10.1126/science.1187659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu X, et al. Maturation and diversity of the VRC01 antibody lineage over 15 years of chronic HIV-1 infection. Cell. 2015;161:470–485. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou T, et al. Structural basis for broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 by antibody VRC01. Science. 2010;329:811–817. doi: 10.1126/science.1192819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekiert DC, et al. Cross-neutralization of influenza A viruses mediated by a single antibody loop. Nature. 2012;489:526–532. doi: 10.1038/nature11414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong M, et al. Antibody recognition of the pandemic H1N1 influenza virus hemagglutinin receptor-binding site. J Virol. 2013;87:12471–12480. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01388-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt AG, et al. immunogenic stimulus for germline precursors of antibodies that engage the influenza hemagglutinin receptor-binding site. Cell Rep. 2015;13:2842–2850. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.11.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt AG, et al. Viral receptor-binding site antibodies with diverse germline origins. Cell. 2015;161:1026–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whittle JR, et al. Broadly neutralizing human antibody that recognizes the receptor-binding pocket of influenza virus hemagglutinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14216–14221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111497108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:531–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers GN, Paulson JC. Receptor determinants of human and animal influenza virus isolates: differences in receptor specificity of the H3 hemagglutinin based on species of origin. Virology. 1983;127:361–373. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ha Y, Stevens DJ, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. X-ray structure of the hemagglutinin of a potential H3 avian progenitor of the 1968 Hong Kong pandemic influenza virus. Virology. 2003;309:209–218. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shinya K, et al. Avian flu: influenza virus receptors in the human airway. Nature. 2006;440:435–436. doi: 10.1038/440435a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robertson JS, et al. Structural changes in the hemagglutinin which accompany egg adaptation of an influenza A (H1N1) virus. Virology. 1987;160:31–37. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito T, et al. Differences in sialic acid–galactose linkages in the chicken egg amnion and allantois influence human influenza virus receptor specificity and variant selection. J Virol. 1997;71:3357–3362. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3357-3362.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Q, Wang W, Cheng X, Zengel J, Jin H. Influenza H1N1 A/Solomon Island/3/06 virus receptor-binding specificity correlates with virus pathogenicity, antigenicity and immunogenicity in ferrets. J Virol. 2010;84:4936–4945. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02489-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faenzi E, et al. One dose of an MF59-adjuvanted pandemic A/H1N1 vaccine recruits pre-existing immune memory and induces the rapid rise of neutralizing antibodies. Vaccine. 2012;30:4086–4094. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moody MA, et al. H3N2 influenza infection elicits more cross-reactive and less clonally expanded anti-hemagglutinin antibodies than influenza vaccination. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kepler TB, et al. Reconstructing a B cell clonal lineage. II. Mutation, selection and affinity maturation. Front Immunol. 2014;5:170. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kepler TB. Reconstructing a B cell clonal lineage. I. Statistical inference of unobserved ancestors. F1000Res. 2013;2:103. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.2-103.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weis W, et al. Structure of the influenza virus hemagglutinin complexed with its receptor, sialic acid. Nature. 1988;333:426–431. doi: 10.1038/333426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson KJ, et al. Human responses to influenza vaccination show seroconversion signatures and convergent antibody rearrangements. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan YC, et al. High-throughput sequencing of natively paired antibody chains provides evidence for original antigenic sin shaping the antibody response to influenza vaccination. Clin Immunol. 2014;151:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wrammert J, et al. Broadly cross-reactive antibodies dominate the human B cell response against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection. J Exp Med. 2011;208:181–193. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scholtissek C, von Hoyningen V, Rott R. Genetic relatedness between the new 1977 epidemic strains (H1N1) of influenza and human influenza strains isolated between 1947 and 1957 (H1N1) Virology. 1978;89:613–617. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakajima K, Desselberger U, Palese P. Recent human influenza A (H1N1) viruses are closely related genetically to strains isolated in 1950. Nature. 1978;274:334–339. doi: 10.1038/274334a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozlov JV, et al. On the origin of the H1N1 (A/USSR/90/77) influenza virus. J Gen Virol. 1981;56:437–440. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-56-2-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J, et al. Molecular-level analysis of the serum antibody repertoire in young adults before and after seasonal influenza vaccination. Nat Med. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nm.4224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nm.4224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Liao HX, et al. High-throughput isolation of immunoglobulin genes from single human B cells and expression as monoclonal antibodies. J Virol Methods. 2009;158:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moody MA, et al. HIV-1 gp120 vaccine induces affinity maturation in both new and persistent antibody clonal lineages. J Virol. 2012;86:7496–7507. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00426-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavinder JJ, et al. Identification and characterization of the constituent human serum antibodies elicited by vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:2259–2264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317793111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeKosky BJ, et al. In-depth determination and analysis of the human paired heavy- and light-chain antibody repertoire. Nat Med. 2015;21:86–91. doi: 10.1038/nm.3743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmidt AG, et al. Preconfiguration of the antigen-binding site during affinity maturation of a broadly neutralizing influenza virus antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:264–269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218256109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization Global Influenza Surveillance Network. Manual for the Laboratory Diagnosis and Virological Surveillance of Influenza. World Health Organization Press; Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cowtan K, Main P. Miscellaneous algorithms for density modification. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:487–493. doi: 10.1107/s0907444997011980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Diffraction data are included in the Protein Data Bank depositions. Antibody sequences were deposited in GenBank. Plasmids for protein expression are available upon request.