Abstract

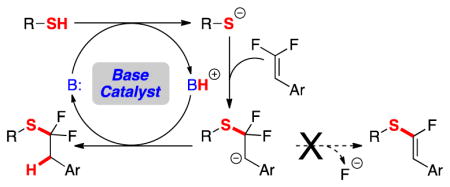

A nucleophilic addition reaction of aryl thiols to readily available β,β-difluorostyrenes provides α,α-difluoroalkylthioethers. The reaction proceeds through an unstable anionic intermediate, prone to eliminate fluoride and generate α-fluorovinylthioethers. However, the use of base-catalysis overcomes the facile β-fluoride elimination, generating α,α-difluoroalkylthioethers in excellent yields and selectivities.

Graphical Abstract

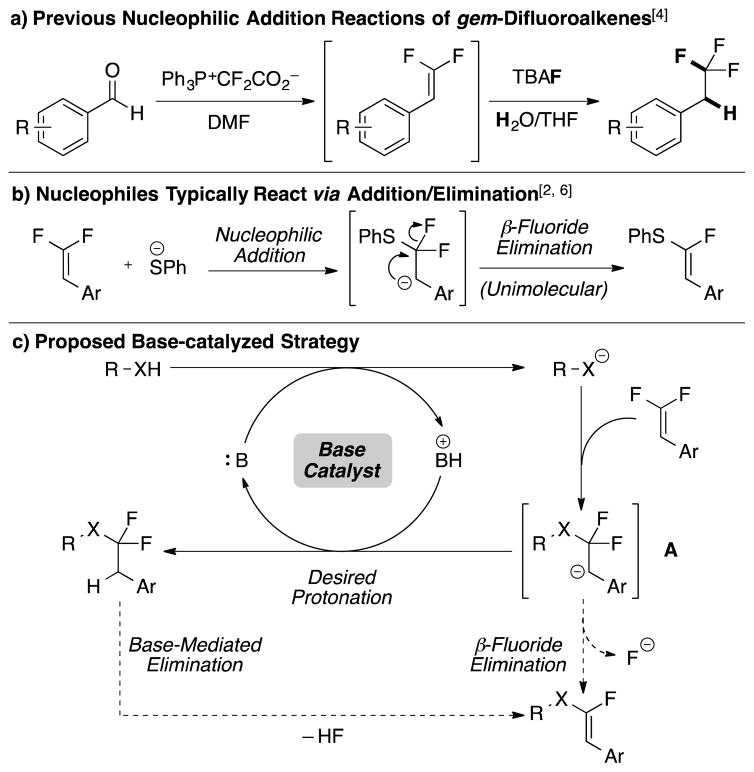

Functionalization reactions of alkenes are essential transformations for synthetic organic chemistry. Although many of these reactions occur via interactions of the alkene HOMO with electrophiles,1 alkenes also react with nucleophiles through the π* LUMO. To access the LUMO, alkenes typically require activation by a limited set of π-electron-withdrawing groups (EWG), such as carbonyl, nitrile, or nitro groups.1b Similar to these EWGs, fluorinated substituents also activate alkenes for nucleophilic attack.2 Unlike EWGs that activate the π bond through resonance and facilitate attack at the β-carbon,3 fluorination activates the alkene’s α-carbon for attack4 through σ-withdrawing inductive effects, while also deactivating the β-carbon through resonance effects.5 This activation of alkenes by fluorine has been utilized in nucleophilic hydrofluorination reactions to generate trifluoromethanes (Scheme 1a),4 and in various acid-promoted intramolecular or base-mediated intermolecular C–F functionalization reactions to deliver monofluorinated products.2, 6 However, nucleophilic hydrofunctionalization reactions of difluoroalkenes with alternate nucleophiles have not been generally developed.

Scheme 1.

Base Catalyst Enables Nucleophilic Addition to gem-Difluoroalkenes.

Inspired by the use of gem-difluoroalkenes as mechanism-based inhibitors,7 we envisioned that alternate heteroatom-based nucleophiles, such as thiols, might undergo analogous hydrofunctionalization reactions by nucleophilic addition followed by protonation. However, prior attempts to add thiols across gem-difluoroalkenes afforded α-fluorovinylthioether products through an addition / elimination process (Scheme 1b).2, 6b, 8 To avoid the elimination of F−, we present a mild, base-catalyzed reaction to furnish α,α-difluoroalkylthioethers in high yield and selectivity (Scheme 1c), which complements earlier methods to access the α,α-difluoroalkylthioether group, including: 1) nucleophilic substitution reactions of silyated9 or halogenated10 difluoroalkyl intermediates that require multi-step preparations; 2) radical processes with limited functional group compatibility;10b, 10c, 11 or 3) oxidative methods that utilize harsh fluorinating reagents.12 In contrast, the present reaction uses only catalytic quantities of a mild base, enabling access to products bearing many sensitive functional groups. Thus, this reaction should facilitate access to bioactive compounds bearing α,α-difluoroalkylthioethers, including anti-cancer13 and anti-inflammatory14 agents and agrichemicals.15

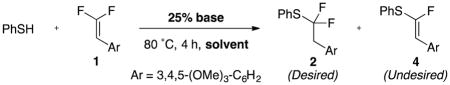

After extensive optimization, we identified a general base-catalyzed protocol for adding aryl thiols to β,β-difluorostyrenes. We selected a styrene-based substrate to stabilize the proposed intermediate anion (A) through resonance. Initial attempts to functionalize difluorostyrene 1 with thiophenol involved catalytic amounts of inorganic bases, which either generated non-fluorinated disubstituted alkene 3 (likely arising from sequential C–F functionalizations),8a, 8b or which did not react (Figure 1). When higher quantities of inorganic base were employed, large amounts of α-fluorovinylthioethers formed. In contrast, catalytic quantities of organic bases generated the desired α,α-difluoroalkylthioether in modest to excellent yield and selectivity. Of the bases evaluated 1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine (TMG) provided the best yield and selectivity for product 2 over product 4 (entries 1–4). Notably, the use of preformed PhSNa as a base only formed small amounts of eliminated product 4 (entry 5), which suggests that ArSH might not serve as the H+ donor, but rather TMG–H+. Subsequent evaluation of solvents revealed that chlorinated solvents provided the best yield and selectivity, with 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE) proving optimal (entries 1, 5–11).

Figure 1.

Undesired Reactivity with Inorganic Bases.

Several experiments support the proposed addition / protonation pathway over a mechanism involving S-based radicals. First, the reaction ran smoothly in the absence of light and O2, which are known radical initiators. Second, although the reaction utilizes TMG (which can have inorganic impurities that can oxidize a thiolate)16, other amine bases that lack such impurities (e.g. purified Et3N) are competent base catalysts (Table 1, entry 2). Third, when running the reaction in CD2Cl2 (which can transfer •D)17 D was, not incorporated into the product. Fourth, reactions run in presence of radical traps (e.g. 1,4-dicyanobenzene and BHT) proceed to full conversion and comparable yields. In contrast, reactions run in the presence of TEMPO, both with and without TMG, gave no desired product and generated (PhS)2, presumably by transfer of H• from PhSH to TEMPO and subsequent homocoupling of the resulting PhS•. Thus under our conditions, S-based radicals are not likely reactive intermediates.

Table 1.

Optimization of the Reaction Conditions.[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | base | solvent | conv/yield [%][b] | 2:4[b] |

| 1 | TMG | DCE | >99/96 | >25:1 |

| 2 | Et3N | DCE | >99/82 | >25:1 |

| 3 | DMAP | DCE | >99/67 | >25:1[e] |

| 4 | TBD | DCE | >99/77 | >25:1 |

| 5[c] | PhSNa | DCE | 15/<1 | N/A |

| 6 | TMG | PhNO2 | 94/60 | 4:1 |

| 7 | TMG | DMF | >99/36 | 1:1.2 |

| 8 | TMG | PhMe | 56/8 | >25:1 |

| 9 | TMG | MeCN | 83/15 | 1:3.5 |

| 10[d] | TMG | DCM | >99/88 | >25:1 |

| 11[c] | TMG | DCE | >99/91 | >25:1 |

Standard conditions: 1 (1.0 equiv), PhSH (2.0 equiv), solvent (0.50 M), base (25 mol %), 80 °C, 4 h.

Determined by 19F NMR standardized with PhCF3 (1.0 equiv).

Solvent (0.25 M), base (5.0 mol %), 70 °C, 0.5 h.

40 °C.

Reaction generated a sulfoxide side product. TBD = 1,5,7-triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene.

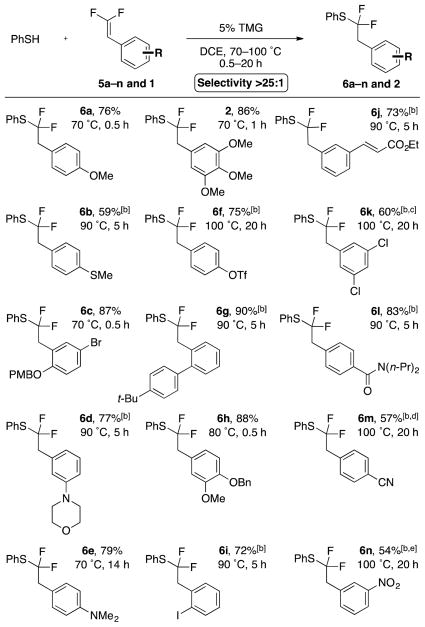

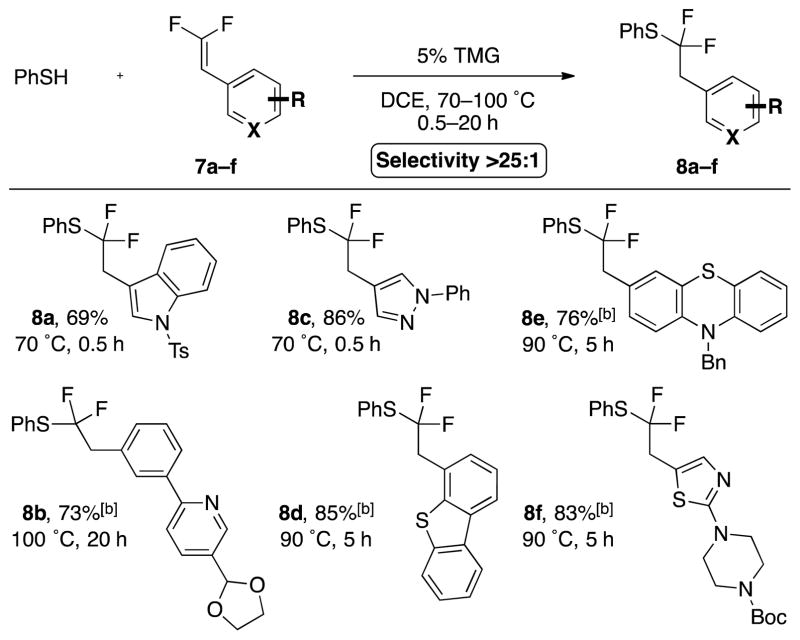

The optimized reaction conditions enabled coupling between thiophenol and a broad spectrum of functionalized β,β-difluorostyrenes (5a–n and 1), with selectivity generally exceeding 25:1 (Scheme 2). The reaction tolerated many useful functional groups on the β,β-difluorostyrene, such as halides (6c, 6i, 6k), ethers (2, 6a–c, 6h), thioethers (6b), and nitrogenous functional groups (6d, 6e, 6l–n). Ortho-substituted β,β-difluorostyrenes required higher reaction temperatures (6c, 6g, 6i). Carbonyl-containing compounds were also tolerated (6j, 6l), and notably a substrate bearing an α,β-unsaturated ester reacted exclusively at the fluorinated position, with no evidence of irreversible Michael addition (6j). Electron-rich and -neutral β̇,β-difluorostyrenes generally provided high yields and selectivities, and required low temperatures and short reaction times (2, 6a–e, 6h). In contrast, under standard reaction conditions, electron-deficient substrates reacted sluggishly, affording products in modest yields and selectivities. To reach full conversion, these reactions required higher temperatures and longer times (6k–n). However, these harsher conditions afforded more α-fluorovinylthioether side product (6.6:1–13:1).

Scheme 2. Scope of Distinct β,β-Difluorostyrenes[a].

[a] Standard conditions: 5a–n (1.0 equiv), PhSH (2.0 equiv), TMG (5.0 mol %), DCE (0.25 M), temperature and time as indicated. Selectivity >25:1 as determined by 19F NMR analysis of the reaction mixture, unless otherwise indicated. Yields represent an average of two runs. [b] PhSH (3.0 equiv). [c] Selectivity = 13:1. [d] Selectivity = 6.6:1. [e] Selectivity = 8:1. PMB = 4-methoxybenzyl, Tf = trifluoromethylsulfonate.

To determine whether the reduced selectivity arose from the instability of the product or of the anionic intermediate A, purified products 2, 6d, and 6n were resubjected to the reaction conditions (Scheme 3a). 19F NMR analysis of the reaction mixtures showed no evidence of degradation, suggesting that β-fluoride elimination from A occurs more rapidly for electron-deficient species than for electron-rich or -neutral species (Scheme 3b).

Scheme 3.

Decomposition of Anionic Intermediate A Reduces the Selectivity for e--Deficient Substrates.

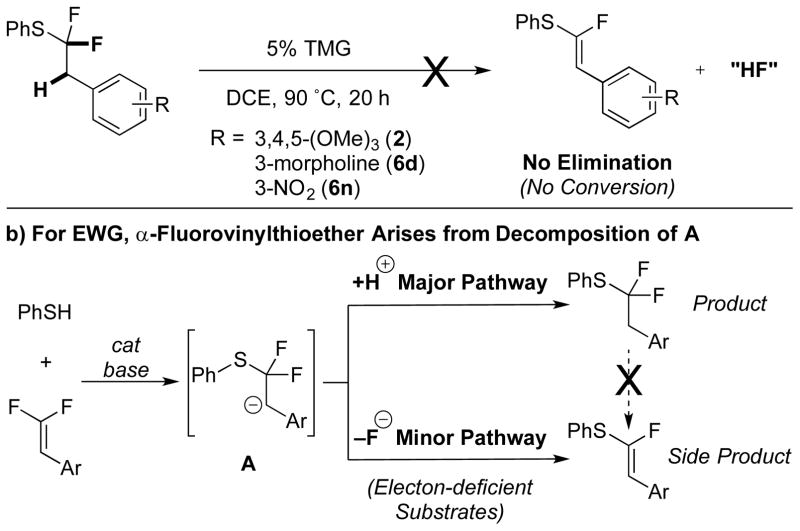

Further, under the optimized conditions heteroaromatic gem-difluoroalkenes reacted smoothly (Scheme 4). Electron-rich and -deficient N-based heterocycles (indole 8a, pyridine 8b, pyrrole 8c), and S-based heterocycles (benzothiophene 8d, phenothiazine 8e, thiazole 8f) all provided good yield and selectivity, suggesting that the reaction conditions should apply to a broad spectrum of biologically relevant heteroaromatic compounds.

Scheme 4.

Scope of Heteroaromatic β,β-Difluorostyrenes.[a]

[a] Standard conditions: 7a–n (1.0 equiv), PhSH (2.0 equiv), TMG (5.0 mol %), DCE (0.25 M), temperature and time as indicated. Selectivity >25:1 as determined by 19F NMR analysis of the reaction mixture. Yields represent an average of two runs. [b] PhSH (3.0 equiv). Ts = 4-toluenesulfonyl.

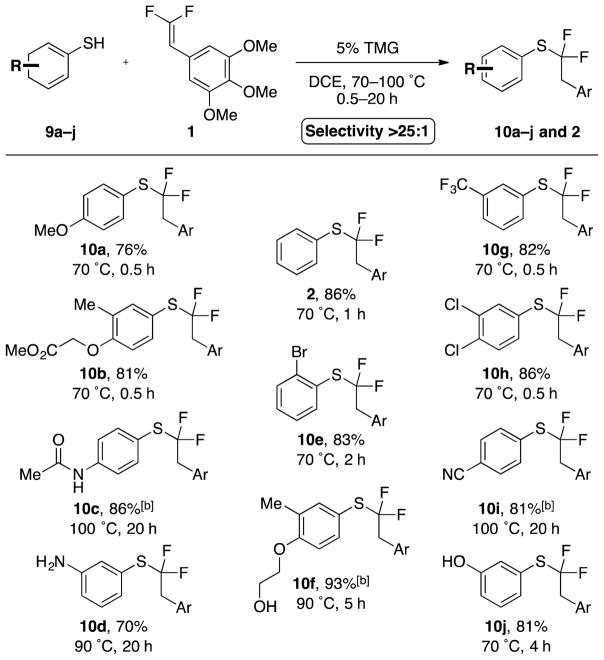

A broad scope of functionalized aryl thiol nucleophiles were also tolerated (Scheme 5). Aryl thiols bearing halides (10h, 10e), ethers (10a, 10b, 10f), trifluoromethane (10g), carbonyl groups (10b), and even a secondary amide (10c) afforded α,α-difluoroalkylthioether products, confirming that electron-rich, -neutral, and -weakly-deficient aryl thiols generally reacted smoothly. Thiols bearing strong electron-withdrawing groups (e.g. nitrile 10i) required higher temperatures and extended reaction times. Notably, all reactions demonstrated excellent selectivity (>25:1) regardless of the nature of the nucleophile. Finally, the mild conditions tolerated many useful protecting groups, including a Ts-protected indole (8a), an acetal (8b), a Boc-protected amine (8f), benzyl- and p-methoxylbenzyl-protected alcohols and amines (6c, 6h, 8e), and an acetyl-protected amine (10c), all potentially useful in multistep synthetic sequences.

Scheme 5.

Scope of Distinct Aryl Thiols.[a]

[a] Standard conditions: 1 (1.0 equiv), ArSH 9a–j (2.0 equiv), TMG (5.0 mol %), DCE (0.25 M), temperature and time as indicated. Selectivity >25:1 as determined by 19F NMR analysis of the reaction mixtures. Yields represent an average of two runs. [b] ArSH (3.0 equiv).

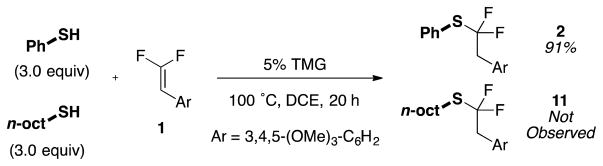

While aryl thiol nucleophiles reacted efficiently, alkyl thiols reacted poorly, giving mainly addition / elimination products, presumably due to a mismatched thiol-base pair. To assess whether a dual nucleophile system could avoid this undesired reactivity of alkyl thiols, an aryl thiol was reacted with 1 in the presence of an alkyl thiol under the harshest conditions explored (Figure 2). Under these conditions, the aryl thiol selectively coupled to form aryl thioether 2 with <1% formation of alkyl thioether 11, likely because the increased acidity of the aryl thiol allows preferential deprotonation, and the resulting thiolate is more nucleophilic than the neutral thiol. Further, attempts to use the present conditions for reactions of alcohol and N-heterocycle nucleophiles proved ineffective. To address this limitation, we are currently optimizing alternate conditions for these nucleophiles.

Figure 2.

Coupling of Aryl Thiol over Alkyl Thiol.

In summary, we developed a new base-catalyzed strategy to generate α,α-difluoroalkylthioethers by directly adding aryl thiol nucleophiles to β,β-difluorostyrenes. This reaction proceeds via an unstable anionic intermediate that is prone to eliminate F−; however, the mild conditions avoid this undesired unimolecular elimination. The catalytic reaction enables access to a variety of functionalized α,α-difluoroalkylthioethers in high yield and selectivity versus the α-fluorovinylthioether. Combined with direct preparations of β,β-difluorostyrenes2 by olefination18 and cross coupling19 chemistry, the present reaction should facilitate access to this underutilized functional group in medicinal and agrichemistry.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the donors of the Herman Frasch Foundation for Chemical Research (701-HF12), and the Madison and Lila Self Graduate Fellowship (D.L.O.) for supporting this work. NMR Instrumentation was provided by NIH Shared Instrumentation Grants S10OD016360 and S10RR024664, NSF Major Research Instrumentation Grants 9977422 and 0320648, and NIH Center Grant P20GM103418. We thank Ms. Caitlin N. Kent of The University of Kansas Department of Medicinal Chemistry for preparing compound 7d.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Experimental procedures, spectroscopic data for new compounds and mechanistic experiments (PDF)

References

- 1.(a) Carey FA, Sundberg RJ. Advanced Organic Chemistry Part B: Reactions and Synthesis. 5. Springer Science & Business Media; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]; (b) Anslyn EV, Dougherty DA. Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. University Science Books; 2006. pp. 545–568. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang X, Cao S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017;58(5):375–392. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Sung HJ, Mang JY, Kim DY. J Fluorine Chem. 2015;178:40–6. [Google Scholar]; (b) Phelan JP, Ellman JA. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2016;12:1203–28. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.12.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Qiao Y, Si T, Yang MH, Altman RA. J Org Chem. 2014;79(15):7122–31. doi: 10.1021/jo501289v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhu L, Li Y, Zhao Y, Hu J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51(47):6150–2. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee CC, Lin ST. J Chem Res. 2000;(3):142–4. [Google Scholar]; (d) Nguyen BV, Burton DJ. J Org Chem. 1997;62:7758–64. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uneyama K. Organofluorine Chemistry. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; New Dehli, India: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Suda M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:2555–2556. [Google Scholar]; (b) Amii H, Uneyama K. Chem Rev. 2009;109:2119–2183. doi: 10.1021/cr800388c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Rogawski MA. Epilepsy Res. 2006;69(3):273–94. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Moore WR, Schatzman GL, Jarvi ET, Gross RS, McCarthy JR. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:360–1. [Google Scholar]; (c) Pan Y, Qiu J, Silverman RB. J Med Chem. 2003;46:5292–3. doi: 10.1021/jm034162s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Fluorine in Pharmaceutical and Medicinal Chemistry: From Biophysical Aspects to Clinical Applications. Imperial College Press; London: 2012. [Google Scholar]; (e) Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology. Wiley-Blackwell; West Sussex, UK: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Timperley CM, Waters MJ, Greenall JA. J Fluorine Chem. 2006;127(2):249–56. [Google Scholar]; (b) Timperley CM. J Fluorine Chem. 2004;125(5):685–93. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kim MS, Jeong IH. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46(20):3545–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Pohmakotr M, Boonkitpattarakul K, Ieawsuwan W, Jarussophon S, Duangdee N, Tuchinda P, Reutrakul V. Tetrahedron. 2006;62(25):5973–85. [Google Scholar]; (b) Li Y, Hu J. J Fluorine Chem. 2008;129(5):382–5. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kosobokov MD, Dilman AD, Struchkova MI, Belyakov PA, Hu J. J Org Chem. 2012;77(4):2080–6. doi: 10.1021/jo202669w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Li Y, Hu J. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46(14):2489–92. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Betterley NM, Surawatanawong P, Prabpai S, Kongsaeree P, Kuhakarn C, Pohmakotr M, Reutrakul V. Org Lett. 2013;15(22):5666–9. doi: 10.1021/ol402631t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang X, Fang X, Yang X, Zhao M, Han Y, Shen Y, Wu F. Tetrahedron. 2008;64(9):2259–69. [Google Scholar]; (c) Choi Y, Yu C, Kim JS, Cho EJ. Org Lett. 2016;18(13):3246–9. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suda M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22(25):2395–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Brigaud T, Laurent E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31(16):2287–90. [Google Scholar]; (b) Furuta S, Kuroboshi M, Hiyama T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36(45):8243–6. [Google Scholar]; (c) Gouault S, Guérin C, Lemoucheux L, Lequeux T, Pommelet JC. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:5061–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon DD, Grina J, Josey JA, Rizzi JP, Schlachter ST, Wallace EM, Wang B, Wehn P, Xu R, Yang H. Preparation of cyclic sulfone and sulfoximine analogs as HIF-2α inhibitors. 2015095048. WO. 2015

- 14.Chen W, Igboko EF, Lin X, Lu H, Ren F, Wren PB, Xu Z, Yang T, Zhu L. Preparation of 1-(cyclopent-2-en-1-yl)-3-(2-hydroxy-3-(arylsulfonyl)phenyl)urea derivatives as CXCR2 inhibitors. 2015181186. WO. 2015

- 15.(a) Kumamoto K, Miyazaki H. Preparation of sulfanylmethylpyrazole derivatives and analogs as pesticides. 2009028727. WO. 2009; (b) Dallimore JWP, El Qacemi M, Kozakiewicz AM, Longstaff A, Mclachlan MMW, Peace JE. Preparation of herbicidal isoxazoline derivatives. 2011033251. WO. 2011

- 16.We thank a reviewer for noting the potential of trace impurities in TMG to initiate a radical reaction.

- 17.Bohm A, Bach T. Chemistry. 2016;22(44):15921–15928. doi: 10.1002/chem.201603303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Zheng J, Lin JH, Cai J, Xiao JC. Chem Eur J. 2013;19(45):15261–6. doi: 10.1002/chem.201303248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zheng J, Cai J, Lin JH, Guo Y, Xiao JC. Chem Commun. 2013;49(68):7513–5. doi: 10.1039/c3cc44271c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Krishnamoorthy S, Kothandaraman J, Saldana J, Prakash GKS. Eur J Org Chem. 2016;2016(29):4965–9. [Google Scholar]; (d) Gao B, Zhao Y, Hu M, Ni C, Hu J. Chem Eur J. 2014;20(25):7803–10. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Hu M, Ni C, Li L, Han Y, Hu J. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(45):14496–501. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b09888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gogsis TM, Sobjerg LS, Lindhardt AT, Jensen KL, Skrydstrup T. J Org Chem. 2008;73:3404–10. doi: 10.1021/jo7027097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ichitsuka T, Takanohashi T, Fujita T, Ichikawa J. J Fluorine Chem. 2015;170:29–37. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.