Abstract

Copper salts find widespread use in Pd-catalyzed oxidation reactions, and they are typically used as oxidants or redox-active cocatalysts. Here, we probe the origin of a dramatic acceleration effect of Cu(OTf)2 in the C–H/C–H aerobic oxidative coupling of o-xylene. NMR spectroscopic analysis of the PdII catalyst in the presence of Cu(OTf)2, together with other experimental and DFT computational studies of the catalytic reaction show that Cu(OTf)2 activates the PdII catalyst for C–H activation via a non-redox pathway and has negligible impact on catalyst reoxidation. These observations led to the testing of other metal triflate salts as cocatalysts, the results of which show that Fe(OTf)3 is even more effective than Cu(OTf)2.

Graphical abstract

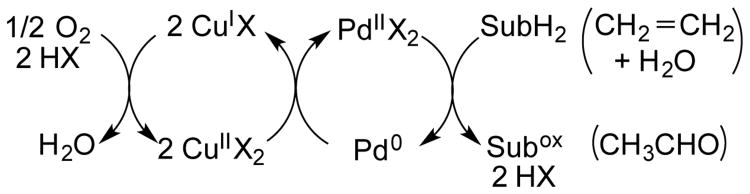

Copper(II) salts are widely used as stoichiometric or cocatalytic oxidants in Pd-catalyzed oxidation reactions. This practice originated more than 50 years ago with the discovery of the Wacker process for oxidation of ethylene to acetaldehyde,1 wherein CuII mediates the aerobic oxidation of Pd0 to PdII (Scheme 1). Later studies of alkene oxidation reactions suggested that CuII could play other roles in the Pd-catalyzed oxidation reactions.2 For example, Murahashi and coworkers proposed that a bimetallic PdII-CuII species serves as the active species on the basis of optimal activity at a 1:1 Pd:Cu ratio,2a and they later isolated bimetallic Pd-Cu complexes from Wacker-type reaction conditions.3,4 Stoichiometric or catalytic CuII salts are also commonly used in Pd-catalyzed C–H oxidation methods,5 and the CuII is typically assumed to serve as an oxidant or redox-active cocatalyst. Pd-catalyzed C–H/C–H oxidative coupling of (hetero)arenes represents a particularly important class of reactions.6 Many of these reactions require (super)stoichiometric quantities of CuII, Ag+, or related oxidants to afford product in good yield. We have been interested in developing and gaining a mechanistic understanding of the C–H/C–H oxidative coupling reactions compatible with O2 as the oxidant. 7 The oxidative homocoupling of o-xylene is a reaction of commercial importance as a potential route to the biaryl monomer used to prepare Upilex, a high-performance polyimide resin.8 This reaction presents an ideal opportunity to probe the mechanism of aerobic C–H/C–H oxidative coupling. The present study analyzes the significant rate-acceleration observed when Cu(OTf)2 is used as a cocatalyst. Evidence that CuII does not play a redox role and observation of improved cocatalysis by non-traditional metal salts have important implications for the field of Pd oxidation catalysis.

Scheme 1. Classical Role of Cu Cocatalysts in Pd-Catalyzed Oxidation Reactions (cf. Wacker Process).

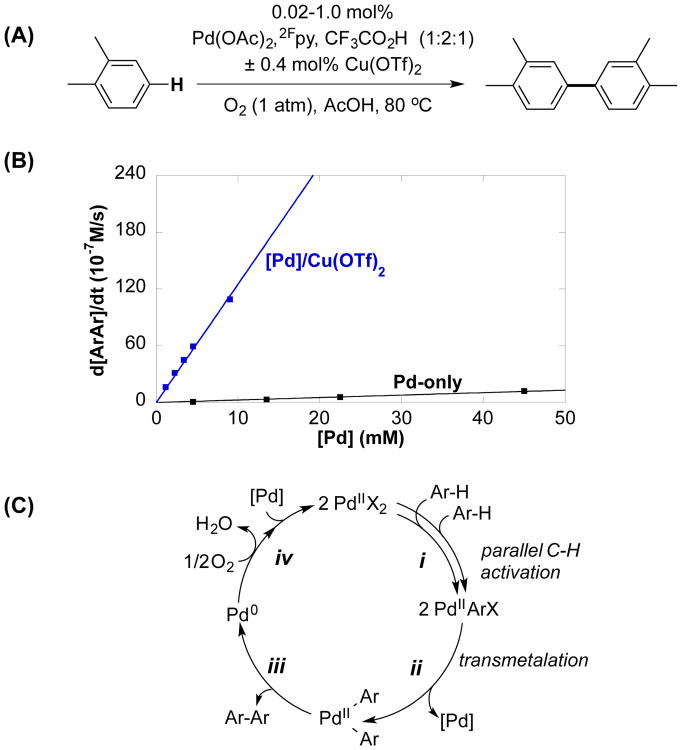

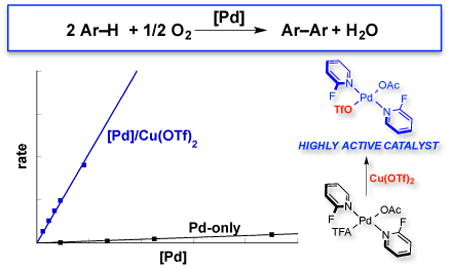

The combination of Pd(OAc)2, 2-fluoropyridine (2Fpy) and CF3CO2H (TFAH) in a 1:2:1 ratio, hereafter designated [Pd], was recently identified as a very effective catalyst for the oxidative coupling of o-xylene,7a and it exhibits high activity and regioselectivity for the formation of 3,3′,4,4′-tetramethylbiphenyl (Figure 1A). A number of different Cu salts were tested in an effort to further improve the catalyst performance (Figure S17). Whereas Cu(OAc)2, Cu(TFA)2, CuBr2 and Cu(BF4)2·6H2O had negligible effect or decreased the catalyst performance, Cu(OTf)2 (OTf = trifluoromethanesulfonate) had a very beneficial impact, increasing the rate by ≥45-fold (Figure 1B). These observations raised questions concerning the origin of the Cu(OTf)2-based rate acceleration. A recent mechanistic study of the same reaction with a Pd-only catalyst system (i.e., lacking the Cu(OTf)2 cocatalyst)7c revealed that the turnover-limiting step is PdII-mediated C–H activation or aryl transmetalation between two PdII–Ar species, depending on the reaction conditions (steps i or ii, Figure 1B). These observations suggest that the rate acceleration observed with Cu(OTf)2 arises from the influence of Cu(OTf)2 on these steps, neither of which is a redox process.

Figure 1.

Pd-catalyzed oxidative coupling of o-xylene promoted by Cu(OTf)2 (A, B) and considerations of the role of Cu in the catalytic mechanism (C). Reaction conditions: [o-xylene] = 4.5 M (4 mmol), AcOH (0.4 mL), O2 (1 atm), 80 °C, [Pd] = 0.9–9.0 mM ([Pd]/Cu) or 4.5–45 mM (Pd-only), [Cu(OTf)2] = 18.0 mM, [Pd] = Pd(OAc)2/2Fpy/CF3CO2H (1:2:1).

The kinetic data in Figure 1B show that biaryl coupling in the presence of Cu(OTf)2 exhibits a first-order dependence on [Pd] throughout the entire range of catalyst concentrations. This result contrasts previous observations with the Pd-only catalyst, which showed a second-order [Pd] dependence at very low [Pd], reflecting turnover-limiting transmetalation.7c Deuterium kinetic isotope effect (KIE) measurements obtained from the independent reaction rates of o-xylene and o-xylene-d10 reveals a primary KIE, kH/kD = 5.3 ± 0.2.9 These results suggest that, for the [Pd]/Cu(OTf)2 catalyst system, C–H activation is the sole turnover-limiting step under all conditions tested.

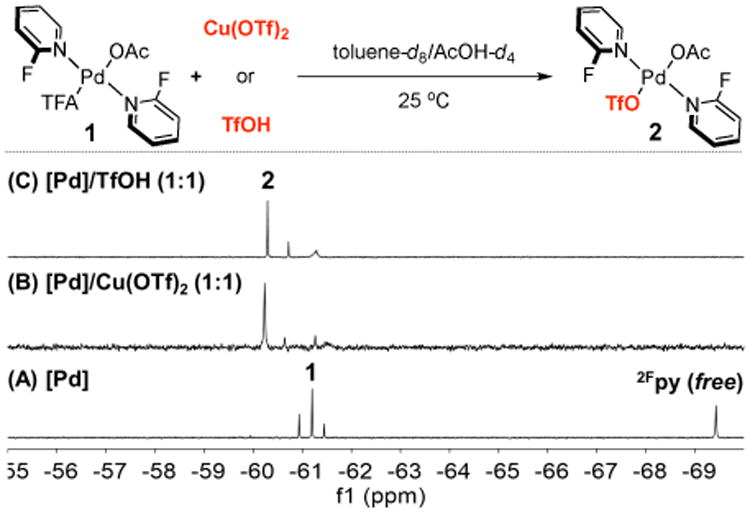

NMR spectroscopic studies were carried out to probe the effects of Cu(OTf)2 on catalyst speciation. Analysis of the [Pd] catalyst system in the absence of Cu(OTf)2 by 19F{1H}NMR spectroscopy reveals the presence of four peaks corresponding to free 2-fluoropyridine (2Fpy) and three PdII-coordinated 2Fpy peaks (Figure 2A).10 The latter correspond to three different (2Fpy)2PdX2 complexes, in which the two X ligands consist of two OAc, two TFA and mixed OAc/TFA.9 The mixed OAc/TFA complex 1 is the major species. Addition of Cu(OTf)2 to this solution results in the formation of a new major species 2, with a 19F chemical shift at −60.2 ppm that remains in a region consistent with 2Fpy coordination to PdII (Figure 2B).11 We speculated that the 2Fpy peak of 2 could arise from anionic ligand exchange between PdII and CuII. Addition of one equivalent of TfOH to a solution of the [Pd] catalyst in the absence of Cu(OTf)2 led to an 19F{1H}NMR spectrum (Figure 2C) nearly identical to that observed with the 1:1 mixture of [Pd]/Cu(OTf)2, and titration experiments reveal that the concentration of 2 maximizes at 2Fpy:Pd = 2:1 and TfOH:Pd = 1:1 (see Supporting Information, Figure S7 and S8).12 Collectively, these data indicate that both Cu(OTf)2 and TfOH lead to the same anionic ligand exchange at PdII to generate (2Fpy)2Pd(OTf)(OAc) (2) as the major species.

Figure 2.

19F{1H}NMR spectra of [Pd], [Pd]/Cu(OTf)2 (1:1) and [Pd]/TfOH (1:1) systems. NMR conditions: 5 mM [Pd], toluene-d8/AcOH-d4 (1:1), fluorobenzene as internal standard (δ = -113.40 ppm). For clarification, only the 2Fpy region of the spectra (-55 to -70 ppm) were shown. [Pd] = Pd(OAc)2/2Fpy/CF3CO2H (1:2:1).

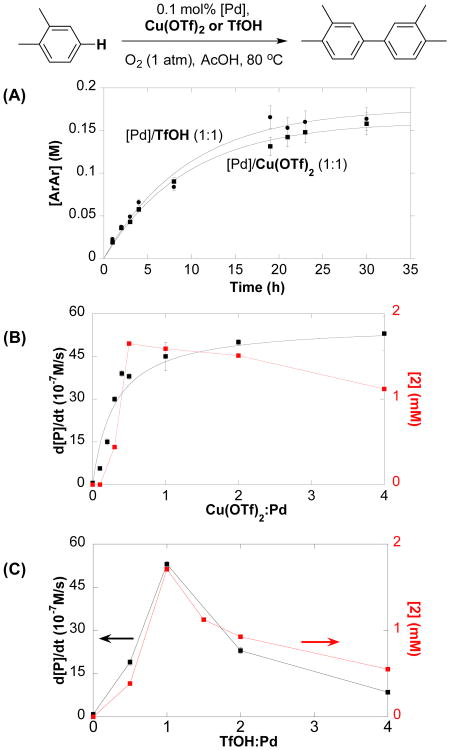

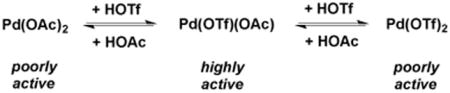

These Pd-speciation studies were then complemented by assessment of the effect of Cu(OTf)2 and TfOH on the catalytic reaction (Figure 3). Time-course data for the oxidative coupling of o-xylene show that [Pd]/Cu(OTf)2 (1:1) and [Pd]/TfOH (1:1) catalyst systems exhibit nearly identical performance (Figure 3A). Addition of >1 equiv Cu(OTf)2 exhibit saturation behavior with respect to the catalytic rate (Figure 3B, black data), whereas TfOH shows a maximum rate at Pd:TfOH = 1:1 (Figure 3C; black data). The catalytic rates observed at different [Cu(OTf)2] and [TfOH] closely correlate with the concentration of species 2 detected by 19F NMR spectroscopy under the analogous conditions (Figures 3B and 3C, red data). These observations suggest that the mixed-anion Pd(OTf)(OAc) species 2 is much more active than PdII species bearing other combinations of OAc, TFA, OTf anionic ligands, and the different profiles observed for Cu(OTf)2 and TfOH in Figures 3B and 3C are attributed to the different anion-exchange equilibria associated with these additives (e.g., eq 1). This proposal is consistent with NMR data showing that higher concentrations TfOH, more so than Cu(OTf)2, deplete the Pd(OTf)(OAc) species, thereby accounting for the inhibition observed at elevated [TfOH]. This anionic ligand exchange hypothesis and evidence for the high activity of the Pd(OTf)(OAc) species 2 accounts for the lack of rate enhancement with other CuII additives, such as Cu(OAc)2, CuBr2 and Cu(BF4)2 (see above).

Figure 3.

(A) Reaction profiles of catalytic oxidative biaryl coupling with [Pd]/Cu(OTf)2 and [Pd]/TfOH systems. (B) and (C): Dependences of initial rates and concentration of species 2 (19F NMR) on [Cu(OTf)2] and [TfOH]. Reaction conditions: [o-xylene] = 4.5 M (4 mmol), [Pd] = 4.5 mM (0.004 mmol), [Cu(OTf)2] = 0–45 mM (0–0.04 mmol), [TfOH] = 0–18 mM (0–0.016 mmol). AcOH (0.4 mL), O2 (1 atm), 80 °C, 0–4 h for initial rate studies. NMR conditions: [Pd] = 5 mM, [Cu(OTf)2] = 0–20 mM, [TfOH] = 0–20 mM, toluene-d8/AcOH-d4 (1:1).

|

(1) |

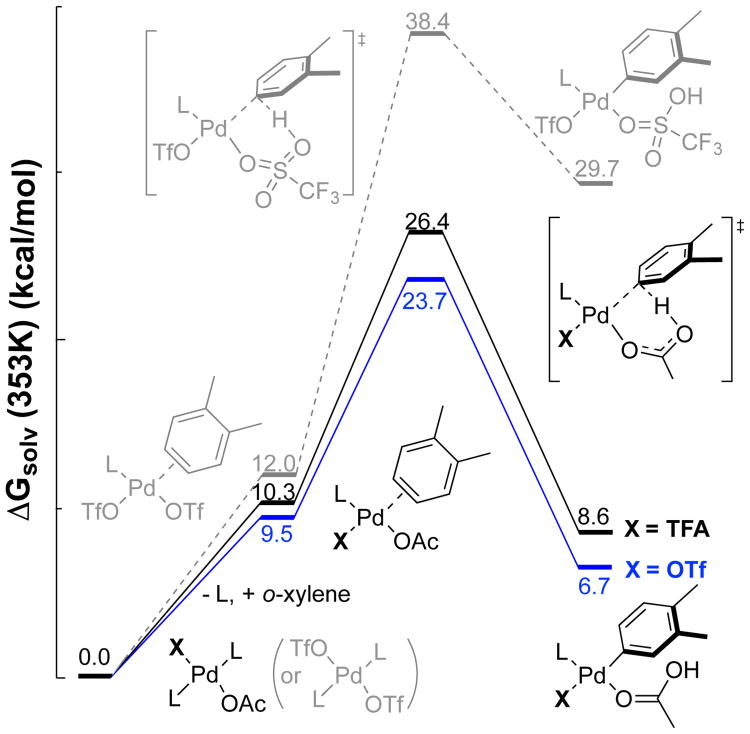

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations provided insight into the origin of anionic ligand effects (Figure 4).9 Analysis focused on the turnover-limiting C–H activation step, starting from resting-state (2Fpy)2PdX2 species (X = OAc, TFA, OTf) and free o-xylene. The results show that the mixed OAc/OTf complex has a significantly lower C–H activation barrier, relative to the OAc/TFA species present under the Pd-only conditions and the bis-OTf complex that forms in the presence of elevated TfOH.13 The free energies of activation determined for the OAc/TFA and OAc/OTf species reveal a ΔΔG‡ of 2.7 kcal/mol (26.4 vs 23.7 kcal/mol). This value aligns with the 45-fold difference in rate observed between the Pd-only and [Pd]/Cu(OTf)2 catalyst systems (cf Figure 1B), for which Pd(TFA)(OAc) and Pd(OTf)(OAc) species are proposed as the active catalyst. These relative barriers for the different PdX2 species may be rationalized on the basis of a “concerted-metalation-deprotonation” mechanism for C–H activation,14,15 which benefits from the synergistic combination of a weakly coordinating anion to enhance the electrophilicity of the PdII center, and a basic carboxylate to deprotonate the coordinated arene en route to a PdII–aryl species.16

Figure 4. DFT computation on the C–H activation step of o-xylene from a Pd(TFA)(OAc) center (black), Pd(OTf)(OAc) center (blue) and Pd(OTf)2 center (gray); see Supporting Information for additional details.

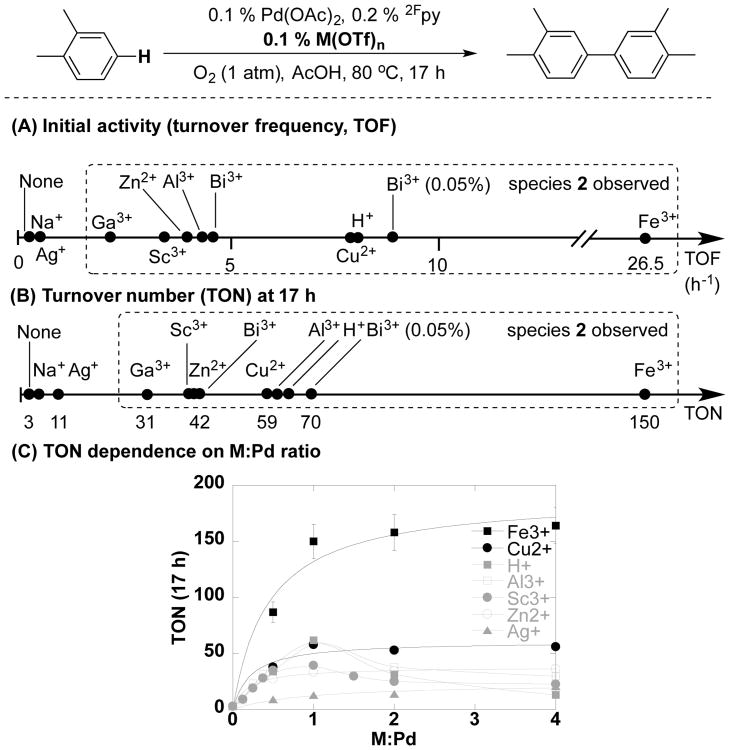

The above studies, in particular, the nearly identical effect of 1 equiv of Cu(OTf)2 and TfOH evident in Figure 3A, demonstrate that the Cu(OTf)2 cocatalyst is primarily playing a non-redox role in the catalytic reaction. The different concentration effects Cu(OTf)2 and TfOH in Figures 3B and 3C, however, prompted us to conduct an empirical test of other metal triflates, with different cation charge and redox properties (Figure 5). The different additives/cocatalysts were compared with respect to their effect on the rate and the turnover number at extended reaction times (17 h) (Figures 5A and 5B). Consistent with the proposed non-redox role of Cu(OTf)2, several of the most effective triflate salts have non-redox-active cations (e.g., Zn2+, Al3+, Bi3+), and in several cases exhibit an effect nearly identical to that of Cu(OTf)2 and TfOH (Figure 5B). The Lewis acidity of the cation appears to be important, as monovalent cations such as Ag+ and Na+ are considerably less effective than di- and trivalent metal cations. 19F NMR analysis of solutions of the Pd catalyst with the different salts show that only the di- and trivalent metal salts lead to the formation of species 2; this species is not formed in solution with AgOTf or NaOTf (cf. Figure S10). And, more details analysis of the effect of Al(OTf)3 show that catalytic activity at different [Al(OTf)3] roughly correlates with amount of 2 present in solution (Figure S19). These observations provide additional support for the role of partial anion exchange at PdII as the basis for enhancement of catalytic activity.

Figure 5.

Pd-catalyzed oxidative biaryl coupling with various metal triflate additives. Reaction conditions: [o-xylene] = 4.5 M (4 mmol), [Pd(OAc)2] = 4.5 mM (0.004 mmol), [2Fpy] = 9.0 mM (0.008 mmol), [M(OTf)n] = 0–18 mM (0–0.016 mmol), AcOH (0.4 mL), O2 (1 atm), 80 °C, 2 h (TOF) or 17 h (TON).

Among the cocatalysts tested, Fe(OTf)3 proved to be an unexpected outlier, leading to a significant enhancement in catalytic rate and turnover numbers relative to Cu(OTf)2 and the other cocatalysts. Iron salts have been used previously in Pd-catalyzed oxidation reactions,17 but their use is rare relative to CuII salts. The Fe(OTf)3 effects are not readily rationalized solely on the basis of the anionic-ligand-exchange hypothesis that explains the role of the other triflate sources in Figure 5. NMR analysis of the catalyst system containing Fe(OTf)3 reveals that the concentration of 2 is less than half that observed with Cu(OTf)2 as the cocatalyst. So, a species other than 2 could be contributing to the enhanced activity when Fe(OTf)3 is present. Alternatively, the improvements could arise from enhanced Pd-catalyst stability. Further studies will be needed to elucidate the mechanistic basis for the Fe(OTf)3 effect; however, the empirical results have important implications for Pd oxidation catalysis because they begin to address the challenges of low catalyst activity and stability, which plague many Pd-catalyzed oxidation reactions.

In summary, the results described herein show that the cocatalytic effect of Cu(OTf)2 in Pd-catalyzed oxidative biaryl coupling arises from a non-redox role, involving anionic ligand exchange to generate a Pd(OTf)(OAc) species that is highly active for C–H activation. Subsequent tests showed that other metal triflate salts, including those with redox inactive metal ions, can be equally effective cocatalysts. Even more significantly, Fe(OTf)3 was identified as a uniquely effective cocatalyst that far surpassing the beneficial effect of Cu(OTf)2 and other metal triflates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Desiree M. Bates and Scott D. McCann for helpful suggestion on DFT computation. This project was initiated with financial support from the NIH (R01 GM67173) and completed with support from the NSF through the CCI Center for Selective C–H Functionalization (CHE-1205646). NMR spectroscopy facilities were provided by the NSF (CHE-1048642) and a generous gift from Paul J. Bender. Computational resources were supported in part by the NSF (CHE-0840494).

Footnotes

Supporting Information: Experimental procedures, additional NMR spectroscopic data, reaction time courses, and computational data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Smidt J, Hafner W, Jira R, Sedlmeier J, Sieber R, Rüttinger R, Kojer H. Angew Chem. 1959;71:176. [Google Scholar]

- 2.For leading references, see: Hosokawa T, Uno T, Inui S, Murahashi SI. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:2318.Hosokawa T, Takano M, Murahashi SI. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:3990.Gonçalves JA, da Silva MJ, Piló-Veloso D, Howarth OW, Gusevskaya EV. J Organomet Chem. 2005;690:2996.Anderson BJ, Keith JA, Sigman MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11872. doi: 10.1021/ja1057218.

- 3.Hosokawa T, Nomura T, Murahashi SI. J Organomet Chem. 1998;551:387. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bimetallic catalysts have been proposed in a number of other Pd-catalyzed reactions (e.g., with Ag+, Sc3+, TiIV): Yang YF, Cheng GJ, Liu P, Leow D, Sun TY, Chen P, Zhang X, Yu JQ, Wu YD, Houk KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:344. doi: 10.1021/ja410485g.Anand M, Sunoj RB, Schaefer HF., III J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:5535. doi: 10.1021/ja412770h.Qin S, Dong L, Chen Z, Zhang S, Yin G. Dalton Trans. 2015;44:17508. doi: 10.1039/c5dt02612a.Walker WK, Kay BM, Michaelis SA, Anderson DL, Smith SJ, Ess DH, Michaelis DJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:7371. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b02428.Zhang S, Chen Z, Qin S, Lou C, Senan MA, Liao RZ, Yin G. Org Biomol Chem. 2016;14:4146. doi: 10.1039/c6ob00401f.

- 5.For representative examples, see: Chen X, Li JJ, Hao XS, Goodhue CE, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:78. doi: 10.1021/ja0570943.Stuart DR, Fagnou K. Science. 2007;316:1172. doi: 10.1126/science.1141956.Shi Z, Li B, Wan X, Cheng J, Fang Z, Cao B, Qin C, Wang Y. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:5554. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700590.Dwight TA, Rue NR, Charyk D, Josselyn R, DeBoef B. Org Lett. 2007;9:3137. doi: 10.1021/ol071308z.Wasa M, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14058. doi: 10.1021/ja807129e.Xi P, Yang F, Qin S, Zhao D, Lan J, Gao G, Hu C, You J. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1822. doi: 10.1021/ja909807f.Wei Y, Su W. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:16377. doi: 10.1021/ja109383e.McNally A, Haffemayer B, Collins BSL, Gaunt MJ. Nature. 2014;510:129. doi: 10.1038/nature13389.Shi R, Zhang H, Lu L, Gan P, Sha Y, Zhang H, Liu Q, Beller M, Lei A. Chem Commun. 2015;51:3247. doi: 10.1039/c4cc08925a.Zhang C, Santiago CB, Crawford JM, Sigman MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:15668. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11335.Yang Y, Qiu X, Zhao Y, Mu Y, Shi Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:495. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11569.

- 6.For reviews, see: Ashenhurst JA. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:540. doi: 10.1039/b907809f.Yeung CS, Dong VM. Chem Rev. 2011;111:1215. doi: 10.1021/cr100280d.Liu C, Yuan J, Gao M, Tang S, Li W, Shi R, Lei A. Chem Rev. 2015;115:12138. doi: 10.1021/cr500431s.

- 7.(a) Izawa Y, Stahl SS. Adv Synth Catal. 2010;352:3223. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201000771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Campbell AN, Meyer EB, Stahl SS. Chem Commun. 2011;47:10257. doi: 10.1039/c1cc13632a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang D, Izawa Y, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9914. doi: 10.1021/ja505405u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Shiotani A, Itatani H, Inagaki T. J Mol Catal. 1986;34:57. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kreuz JA, Edman JR. Adv Mater. 1998;10:1229. [Google Scholar]; (c) Alsters PL. Process for the Production of Biaryl Compounds. 2016 Jan 21; WO 2016/008931 A1. [Google Scholar]

- 9.See Supporting Information for details.

- 10.In addition, there are three TFA peaks, corresponding to 2Fpy-ligated Pd(TFA)(OAc), Pd(TFA)2 and TFAH (see Figure S5b). The NMR solvent mixture, toluene-d8/AcOH-d4 (1:1), mimics the catalytic solvent. AcOH is crucial to solubilize Cu(OTf)2 and TfOH.

- 11.Control experiments show that 2Fpy coordination to Cu(OTf)2 results in a broad peak at −71 ppm (see Figure S6). The 2Fpy/PdII peaks remain sharp and exhibit reproducible integrations at [Cu(OTf)2] ≤ 20 mM (see Figure S9).

- 12.Control experiments show that the major peaks in these spectra do not arise from protonation of 2Fpy by TfOH (which exhibits a peak at –74 ppm) and that the TFAH component of the [Pd] catalyst system is not needed to form 2 (see Supporting Information, Figure S6b).

- 13.C–H activation by a Pd(OTf)(TFA) species also exhibits a higher barrier (∼30 kcal/mol; see Figure S20). The lack of effect of[TFAH] on the catalytic reaction rate and turnover numbers provides further evidence that a Pd(OTf)(TFA) species is not involved.

- 14.For leading references, see: Davies DL, Donald SMA, Macgregor SA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13754. doi: 10.1021/ja052047w.García-Cuadrado D, Braga AAC, Maseras F, Echavarren AM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1066. doi: 10.1021/ja056165v.Gorelsky SI, Lapointe D, Fagnou K. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10848. doi: 10.1021/ja802533u.

- 15.Waymouth and coworkers have noted analogous mixed-ligand benefits in oxidation of alcohols by [(neocuproine)Pd(OAc)](OTf): Conley NR, Labios LA, Pearson DM, McCrory CCL, Waymouth RM. Organometallics. 2007;26:5447.

- 16.For comparison, oxidative biaryl coupling has been observed to be promoted under super-acidic conditions, e.g., in TfOH as the solvent. Xu BQ, Sood D, Iretskii AV, White MG. J Catal. 1999;187:358.Iretskii AV, Sherman SC, White MG, Kevin JC, Schiraldi DA. J Catal. 2000;193:49.Liu Y, Wang X, Cai X, Chen G, Li J, Zhou Y, Wang J. ChemCatChem. 2016;8:448.

- 17.See, for example: Larsson EM, Åkermark B. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:2523.Kim D, Ham K, Hong S. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:7305. doi: 10.1039/c2ob26061a.Tanaka Y, Tahahara JP, Setoyama T, Lempers HEB. In: Liquid Phase Aerobic Oxidation Catalysis. Stahl SS, Alsters PL, editors. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co KGaA; Weinheim, Germany: 2016. p. 173.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.