Abstract

The myasthenogenic peptides p195–212 and p259–271 are sequences of the human acetylcholine receptor and were shown to induce myasthenia gravis-associated immune responses in mice. A dual altered peptide ligand (APL) composed of the two APLs of the myasthenogenic peptides inhibited, in vitro and in vivo, those responses. The aims of this study were to elucidate the events that follow the in vivo treatment with the dual APL and to characterize the cell population that is induced by the latter. We demonstrate here that s.c. administration of the dual APL up-regulates CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells that are characterized by up-regulated expression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, intracellular and membranal TGF-β, and Foxp3. Administration of the dual APL to mice concomitant with the immunization with either of the myasthenogenic peptides resulted also in the up-regulation of c-Jun-NH2-terminal kinase activity and of Fas signaling pathway molecules as determined by measuring Fas, Fas ligand, and caspase 8. Thus, our results suggest that the suppression of myasthenia gravis-associated T cell responses exerted by the dual APL is mediated by the CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cell function via TGF-β or cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, which further stimulate a cascade of events that up-regulates apoptosis.

Keywords: immunomodulation, myasthenia gravis, regulatory T cells

Myasthenia gravis (MG) and its experimental animal model, experimental autoimmune MG (EAMG), are immune disorders that are characterized by circulating antibodies and lymphocyte autoreactivity to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AChR), leading to reduced numbers of AChR molecules at the postsynaptic end plates. Weakness and fatigability of voluntary muscles characterize the disease (1, 2).

Two peptides representing sequences of the human AChR α-subunit, namely p195–212 and p259–271, were able to stimulate peripheral blood lymphocytes of patients with MG and were shown to be immunodominant T cell epitopes of SJL and BALB/c mice, respectively (3, 4). A dual altered peptide ligand (APL) composed of the tandemly arranged two single amino acid analogs of the two above peptides was synthesized and tested for its ability to immunomodulate a broader range of MG-associated autoimmune responses. The dual APL was effective in inhibiting the in vivo priming of lymph node (LN) cells to either myasthenogenic peptide (p195–212 or p259–271) and in down-regulating the clinical manifestations of an ongoing EAMG (5, 6). The beneficial effects on the clinical EAMG correlated with a reduced production of anti-AChR antibody, as well as with a decrease in the secretion of IL-2 and, more dramatically, IFN-γ in response to AChR triggering (6). In short-term experiments, the dual APL down-regulated IL-2 and IFN-γ and up-regulated the secretion of IL-10 and the immunosuppressive cytokine TGF-β (7). The dual APL was also found to interfere with both the migratory potential (P/E selectins) and the adhesiveness of LN-derived T cells to vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 of the autoreactive T cells and, furthermore, with the activation of phospholipase C-γ1 and with the secreted levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (7, 8). Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of the dual APL could be adoptively transferred by splenocytes of mice treated with the dual APL, to p195–212 or to Torpedo AChR-immunized mice, as determined by the inhibition of the in vivo priming of LN cells of mice immunized with p195–212 (9).

Administration of the dual APL was also found to increase the CD4+CD25+ T cell population in LN of SJL immunized mice, although the mechanism by which these cells exert their suppressive effects was not elucidated (10). The CD4+CD25+ are regulatory T cells that were first described by Sakaguchi et al. (11). These regulatory T cells, which function in vivo and in vitro, are CD4+ and constitutively express CD25 (IL-2 receptor α chain) on their cell surface. The function of these cells is a complex process, tightly regulated by multiple factors such as Foxp3 that has been recently shown to convert CD4+CD25– T cells into CD4+CD25+ cells with regulatory properties (12). Another molecule that mediates the suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells is cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), a negative costimulatory molecule for T cell activation, constitutively expressed on CD4+CD25+ T cells (13). CTLA-4 can induce TGF-β production, an event that may account at least partially for the CTLA-4 negative regulation (14).

TGF-β is a critical factor in regulation of T cell-mediated immune responses and in the induction of immune tolerance (15). TGF-β signals through a dense network of pathways, one of which is the c-Jun-NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway. TGF-β has been reported to increase the activity of AP-1 (Jun-Fos complexes) through phosphorylation of JNK. Furthermore, the transcription factors that mediate TGF-β signals (and are termed SMADs) have been reported to be phosphorylated by JNK (15). One of the effector systems involved in intracellular transmission of T cell receptor signals are serine/threonine kinase cascades of the mitogen-activated protein kinase type. The JNKs were recently found to commit T cells to stress-induced apoptosis through Fas ligand (FasL) expression and Fas-mediated activation of caspases. Subsequently, caspases stimulate JNK to further up-regulate FasL expression (16).

In the present study, we attempted the characterization of the immunoregulatory T cells that are induced by the dual APL and followed the downstream end result of their function. We demonstrate here that s.c. administration of the dual APL increases CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells that are characterized by elevated expression of CTLA-4, Foxp3, and TGF-β in SJL and BALB/c mice. Furthermore, we determined an up-regulation in JNK activity in T cells of mice that were treated with the dual APL. The latter is associated with an elevation in Fas- and FasL-expressing cells and an elevation in the expression of the caspase 8 gene.

Materials and Methods

Mice. Female mice of the inbred strains SJL (The Jackson Laboratory) and BALB/c (Harlan, Jerusalem) were used at the age of 8–12 weeks. The study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Weizmann Institute of Science.

Synthetic Myasthenogenic Peptides and Dual APL. The synthetic peptides p259–271 (VIVELIPSTSSAV) and p195–212 (DTPYLDITYHFVMQRLPL) were synthesized and characterized as described (5). The dual APL 262Lys-207Ala (VIVKLIPSTSSAVDTPYLDITYHFVAQRLPL) was designed as described (5) and synthesized (97% purity) by UCB-Bioproducts.

Immunization and Treatment of Mice. SJL and BALB/c mice were immunized with 10 μg of p195–212 and p259–271 per mouse, respectively, in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) and were injected either concomitantly or 7 days later with the dual APL (s.c. 200 μg per mouse) in PBS.

Proliferative Responses of LN Cells. Popliteal LN cells (0.5 × 106 per well) obtained from mice 10 days after their immunization were cultured in enriched RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 1% normal mouse serum in the presence of various concentrations of p195–212 for 96 h. [3H]Thymidine [0.5 μCi (1 Ci = 37 GBq) of 5 Ci/mmol (Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences)] was then added, and, 16 h later, plates were harvested onto filter paper and radioactivity was counted.

Secretion and Detection of IFN-γ. LN cells (5 × 106 per ml) of the tested mice were stimulated with p195–212 (5 μM) for 48 h. Supernatants were collected and analyzed for IFN-γ levels by ELISA by using standard, capture, and detecting antibodies for IFN-γ (OptEIA set, Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Antibodies. The following antibodies were used for fluorescence staining: anti-CD25/IL-2R-FITC antibody (clone 7D4), hamster anti-mouse CD152/CTLA-4-phycoerythrin (PE) and their matched isotype controls (Southern Biotechnology Associates), anti-TGF-β-PE (clone TB21) and its matched isotype control (IQ Products, Groningen, The Netherlands), biotinylated chicken anti-TGF-β1 (R & D Systems) and streptavidin-PE (eBioscience, San Diego), hamster anti-mouse-Fas-PE (clone Jo2), hamster anti-mouse CD178 (FasL, CD95 ligand)-PE (clone MFL3) and rat anti-mouse CD4-allophycocyanin (L3T3) antibody (clone 1B8) and their matched isotype controls (Pharmingen). The antibodies that were used for Western blots were anti-JNK2 (Serotec) and antiphosphorylated-JNK, p-JNK (Serotec), as well as anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase and anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories).

Fluorescence Staining of LN Cells. Spleen and LN cells (5–10 × 105 cells per sample) were washed with 5% FCS/PBS, incubated with the relevant antibody, washed again, and analyzed by FACS. For intracellular staining, the cells were incubated with a fixation solution, washed, and resuspended in permeabilization solution (Serotec).

Isolation of T Cells. Petri dishes were coated with 5 ml of goat anti-mouse Ig (15 μg/ml in PBS) overnight at 4°C and washed three times. Cell suspensions of popliteal LNs (50 × 106 per 5 ml in RPMI medium 1640/10% FCS) obtained from the various mouse groups were incubated on the coated plates for 70 min at 4°C. The nonadherent cells, which were mainly T cells (95% as assessed by FACS analysis), were collected, washed in RPMI medium 1640, counted, and used.

Preparation of Cell Lysates. LN cells or purified T cells were incubated for 10 min on ice in the presence of cold lysis buffer (50 × 106 per ml) containing 50 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1% EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mM Na-orthovanadate, 30 mM Na-pyrophosphate, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin (pH 7.2). Lysed cells were then centrifuged for 5 min to remove the DNA. Concentrations of protein were determined by Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad).

Western Blot Analysis. Lysates were boiled in the presence of sample buffer. Equal amounts of proteins were separated on SDS/PAGE by using 10% polyacrylamide and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking, the membrane was reacted with the relevant antibodies. The membrane was further incubated with the second antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase. Detection was carried out by the enhanced chemiluminescence method. Protein expression was determined by photodensitometry using the nih image program.

Real-Time PCR. Levels of mRNA of caspase 8 and Foxp3 were analyzed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR by using LightCycler (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Total RNA was isolated from LN cells, and then the RNA was reverse-transcribed to prepare cDNA by using Moloney's murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega). The resultant cDNA was subjected to real-time PCR according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 20 μl of reaction volume contained 3 mM MgCl2, LightCycler HotStart DNA SYBR Green I mix (Roche), specific primer pairs, and 5 μl of cDNA. PCR conditions were as follows: 10 min at 95°C followed by 35–50 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C, 15 sec at 60°C, and 15 sec at 72°C. Primer sequences (forward and reverse, respectively) were used as follows: caspase 8, 5′-acataacccaactccgaa-3′ and 5′-gtgggataggatacagcaga-3′; Foxp3, 5′-taccacaatatgcgaccc-3′ and 5′-ctcaaattcatctacggtcc-3′; β-actin, 5′-gacgttgacatccgtaaag-3′ and 5′-ggccggactcatcgta-3′.

Results

Inhibition of Proliferation and IFN-γ Production by the Dual APL Is via the Up-Regulation of CD4+CD25+ Cells That Express CTLA-4, Foxp-3, and TGF-β. Fig. 1 demonstrates the ability of the dual APL to inhibit the in vivo priming of LN cells and to down-regulate the secretion of the pathogenic cytokine IFN-γ. Thus, SJL mice were immunized with p195–212 and concomitantly treated with the dual APL. Ten days later, the LN cells were taken for proliferation (Fig. 1A) or tested for IFN-γ secretion (Fig. 1B). Fig. 1A demonstrates that the dual APL inhibited >90% of the proliferative capacity to p195–212. Similarly, Fig. 1B shows that the secretion of IFN-γ by LN cells of the p195–212-immunized SJL mice was down-regulated significantly after administration of the dual APL.

Fig. 1.

The dual APL inhibits the in vivo priming of LN cells and down-regulates the secretion of IFN-γ. SJL mice were immunized with p195–212 in CFA (open bars) and concomitantly treated with the dual APL (200 μg per mouse s.c. in PBS; filled bars). Mice were killed at day 10, and LN cells were taken for proliferation assay (A) or for cytokine secretion (B) as described in Materials and Methods. Results are representative of three experiments performed.

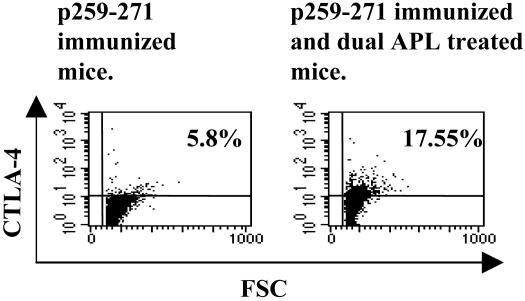

To characterize the population of cells that is up-regulated by the dual APL and is responsible for its suppressive effects, we first determined changes in CTLA-4 expression in the dual APL-treated mice compared with the nontreated mice. To this end, we immunized BALB/c mice with p259–271 and divided them into groups that were injected with the dual APL at day 7, 8, or 9 after the immunization, a stage at which the T cells are already activated by the immunizing peptide. Ten days after the immunization with the peptide, mice were killed and their LN cells were stained intracellularly with anti-CTLA-4-PE. The results of this experiment indicated that, whereas only a slight increase in CTLA-4 expression could be observed 24 h after the administration of the dual APL, a significant increase of 6.2% could be observed at 48 h after administration of the dual APL in comparison to cells of untreated mice. At 72 h after administration of the dual APL, the increase in CTLA-4 staining reached 11.75%. Fig. 2 shows a representative staining of CTLA-4 in cells of mice that were treated with the dual APL at day 7 after immunization, as compared to cells of nontreated mice. These results were reproducible in three different experiments. Therefore, in further experiments the dual APL was injected at day 7 after immunization with the myasthenogenic peptides.

Fig. 2.

CTLA-4 expression in LN cells of BALB/c mice that were treated with the dual APL. BALB/c mice were immunized with p259–271 and treated with the dual APL at day 7 after immunization. Mice were killed at day 10, and their LN cells were stained with anti-CTLA-4-PE and analyzed by FACS. The results presented are after reduction of background staining with the matched isotype control, and they represent one experiment of three performed.

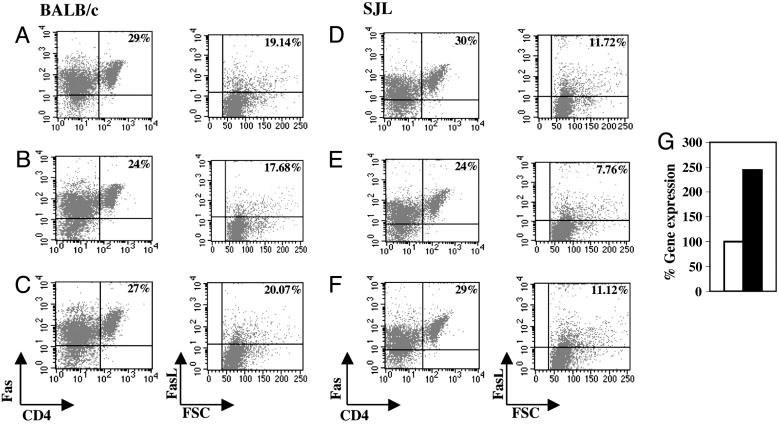

To further characterize the cells that are up-regulated after treatment with the dual APL, we immunized and treated BALB/c mice as described above. Fig. 3 A–C demonstrates the results of LN cells staining for CD4+, CD25+, and CTLA-4+. As can be seen, there is an elevation of 1.6% in the CD4+CD25+ cell population in LN cells of the dual APL-treated mice compared with the nontreated mice. In addition, CD4+ T cells that were also CTLA4+ were up-regulated by 1.8% in the treated mice. When the CD4+CD25+ gated population was also stained for CTLA-4, an elevation of 8.4% could be observed in cells of dual APL-treated mice compared with cells of untreated mice (Fig. 3C). These results were reproducible in all four experiments performed.

Fig. 3.

The effect of treatment with the dual APL on the expression of CD4+CD25+CTLA4+ T cells and on Foxp3 gene expression in BALB/c and SJL mice. BALB/c (A–C) and SJL (D–G) mice were immunized with p259–271 and p195–212, respectively. Seven days after immunization, the mice were treated with the dual APL, and their LN cells were harvested 3 days later. LN cells of BALB/c(A–C) and SJL (D–F) mice were stained for CD4+, CD25+, and CTLA-4. A–F Left demonstrates LN cell staining of mice that were immunized with the myasthenogenic peptides, and A–F Right shows staining of LN cells of mice that were treated with the dual APL in addition to their immunization. CD4+CD25+-gated cells that were also stained for CTLA-4 are shown in C and F. (G) Total RNA was isolated, reverse-transcribed as described in Materials and Methods, and further subjected to real-time PCR of the Foxp3 gene. p195–212-immunized mice (open bar) and dual APL-treated mice (filled bar) are presented. Results are of a representative experiment of four performed.

The same experiments were performed in SJL mice. As can be seen in Fig. 3 D–F, a similar elevation was measured in the CD4+CD25+ T cell population as well as in the CD4+ cells that were also positive for CTLA4 in the dual APL-treated mice compared with the nontreated mice. Moreover, an elevation of 14.35% was observed in the dual APL-treated mice compared with the nontreated mice in the CD4+CD25+ gated population that was also CTLA-4+. For further characterization of the cells induced by the treatment with the dual APL, Foxp3 gene expression was determined in LN cells of immunized and dual APL-treated SJL mice. The results shown in Fig. 3G represent gene expression levels of Foxp3 normalized to β-actin and are presented as a percentage of the levels in the p195–212-immunized group (accounted as 100%). Fig. 3G demonstrates an elevation of 74% in Foxp3 expression in the dual APL-treated mice compared with mice that were immunized only with the peptide. Thus, CD4+CD25+ cells are up-regulated upon treatment with the dual APL as determined by the characteristic markers CTLA-4 and Foxp3.

Because CD4+CD25+ T cells that express CTLA4 were reported to exert at least part of their inhibitory effects by up-regulating TGF-β (17), we measured the expression of intracellular and membranal TGF-β in mice that were immunized with the myasthenogenic peptides and were either treated or not treated with the dual APL. LN cells of BALB/c mice were stained for CD4, CD25, and intracellular TGF-β. Fig. 4 shows an up-regulation in the CD4+CD25+ cell population after treatment with the dual APL. In addition, CD4+ cells that were also positively stained for intracellular TGF-β were up-regulated in the LN cells of dual APL-treated mice by 2.89% compared with the untreated mice (Fig. 4 A and B). Fig. 4 also shows an elevation of 12% in the CD4+CD25+ gated population that was stained for intracellular TGF-β in the dual APL-treated LN cells compared with the nontreated mice (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

The effect of the dual APL on the expression of intracellular and membranal TGF-β in CD4+CD25+ T cells from LN cells of BALB/c and SJL mice. BALB/c (A–C) and SJL (D–G) mice were immunized with p259–271 and p195–212, respectively, and treated with the dual APL 7 days later. LN cells of BALB/c were stained for CD4+, CD25+, and intracellular and membranal TGF-β. Left demonstrates LN cell staining of mice that were immunized with the myasthenogenic peptide alone, and Right shows LN cell staining of mice that were immunized and treated with the dual APL. C and F represent CD4+CD25+-gated cells that were also stained for intracellular TGF-β.(G) CD4+CD25+-gated cells that were also stained for membranal TGF-β. Results are of one experiment of three performed.

A similar experiment was performed in SJL mice and is also presented in Fig. 4. Fig. 4 D and E shows that CD4+ T cells that are also stained for intracellular TGF-β were up-regulated in the dual APL-treated mice compared with the nontreated mice by 2.49%. The CD4+CD25+ gated population that was stained for intracellular TGF-β was elevated by 18% in the dual APL-treated mice compared with the nontreated mice (Fig. 4F). Fig. 4G further demonstrates an up-regulation of 11.9% in the CD4+CD25+ gated population that was also stained for membranal TGF-β after treatment with the dual APL.

The Dual APL Up-Regulates JNK Activity in BALB/c and SJL Immunized Mice. Because T cell activation that culminates in cytokine production, cellular proliferation, and acquisition of effector functions is initiated by the combination of intracellular signals, we studied the possible involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinases in the mechanism of action of the dual APL. To this end, we focused on JNK, which is associated with downstream apoptotic pathways. SJL and BALB/c mice were immunized and concomitantly treated with the dual APL. Whole LN cell lysates or LN-derived purified T cell lysates were prepared and assayed for JNK activity. Fig. 4 shows the blots of the phosphorylated JNK and the total JNK-reacted membranes as well as their quantified densitometry, presented in columns. As can be seen in the blots of Fig. 4, JNK activity in total LN cells (Fig. 5 A and C) and purified T cells (Fig. 5 B and D) was up-regulated after treatment with the dual APL compared with mice that were immunized with the myasthenogenic peptide only. This up-regulation in JNK activity was also seen in spleen cells of dual APL-treated SJL and BALB/c mice (data not shown). The densitometry results demonstrated an elevation of 45% and 70% in JNK activity in total LN cells of SJL and BALB/c mice, respectively. The results with purified T cells indicated an increase of 34% for both SJL and BALB/c mice, suggesting that the elevation in pJNK can be attributed at least in part to T cells. The latter results were reproducible in four experiments.

Fig. 5.

The effect of the dual APL on JNK activity in SJL and BALB/c mice. BALB/c(A and B) and SJL (C and D) mice were immunized with p259–271 and p195–212, respectively (open bars in Top), and concomitantly treated with the dual APL (filled bars in Top). LN cells were harvested 10 days later, and lysates were prepared from total LN cell populations (A and C) or from purified T cells (B and D). Samples (100 μg of protein per lane) were separated on SDS/PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Anti-JNK2 (total JNK; Bottom) or anti-pJNK (Middle) antibodies were applied to the membranes. Protein expression was determined by photodensitometry using the nih image program. Data are from a representative experiment of four performed.

Fas Signaling Pathway Is Enhanced After Treatment with the Dual APL. To further assess the involvement of pathways of apoptosis in the mechanism of action of the dual APL, we looked for changes in the Fas receptor, in its ligand, FasL, and in caspase 8, a protease that acts on downstream proteins in the Fas/FasL signaling cascade. Thus, BALB/c and SJL mice were immunized and treated with the dual APL. Mice that were immunized with PBS in CFA served as controls. The LN and spleen cells were stained for Fas, FasL, and CD4+. Fig. 6 A–F presents dot plots of spleen cell staining of BALB/c and SJL mice. The dot plots in Fig. 6 A–F Left represent the Fas staining on CD4+ T cells, and the dot plots in Fig. 6 A–F Right demonstrate the FasL staining on total spleen cells. A decrease in Fas staining and FasL staining could be observed in the peptide-immunized group compared with the PBS/CFA-immunized group of both strains. The decrease in the percentage of Fas+CD4+ cells in BALB/c and SJL mice immunized with the myasthenogenic peptides was calculated to be 17% and 20% (compared with PBS-immunized mice, accounted as 100%), respectively. However, as can be seen in Fig. 6 C and F, injection with the dual APL up-regulated Fas-expressing CD4 T cells of BALB/c and SJL mice by 12% and 20%, to levels close to those seen in PBS-immunized controls. Similar results were observed when LN cells were stained for Fas-expressing CD4+ cells; however, the differences were less prominent (data not shown). The percentage of FasL-stained cells of BALB/c and SJL mice immunized with the myasthenogenic peptides was down-regulated in comparison with the control immunized mice (considered as 100%), and treating with the dual APL up-regulated FasL-expressing cells to levels close to those seen in the PBS injected controls (Fig. 6 C and F).

Fig. 6.

The effect of the dual APL on Fas/FasL protein expression and on caspase 8 gene expression in BALB/c and SJL mice. BALB/c(A–C) and SJL (D–G) mice were immunized with p259–271 and p195–212, respectively, and concomitantly treated with the dual APL. Mice immunized with PBS in CFA served as controls. Spleen cells were harvested 10 days later and taken for staining of CD4, Fas, and FasL. Alternatively, LN cells were taken for real-time PCR to determine expression of the caspase 8 gene (G). (A and D) Spleen cells of PBS in CFA-injected mice. (B and E) Spleen cells of mice immunized with the myasthenogenic peptide alone. (C and F) Spleen cells of immunized and dual APL-treated mice. (G) Total RNA was isolated and reverse-transcribed to prepare cDNA, which was further subjected to real-time PCR of the caspase 8 gene. p195–212-immunized mice (open bar) and dual APL-treated mice (filled bar) are presented. Results are of a representative experiment of three performed.

We have further determined caspase 8 gene expression on the LN cells of SJL mice that were immunized with p195–212 and either treated or not treated with the dual APL. Fig. 6G demonstrates the levels of the gene expression, normalized to β-actin and presented as a percentage of the levels in the nontreated group (considered as 100%). A significant increase (2.4-fold) was measured after treatment with the dual APL. Thus, the elevation in all of the tested parameters of the Fas signaling pathway, namely, Fas, FasL, and caspase 8, leads eventually to activation-induced cell death (AICD).

Discussion

The main findings of the present study are that the dual APL up-regulates the expression of CD4+CD25+ cells that express elevated levels of characteristic markers such as CTLA-4, intracellular and membrane-bound TGF-β, and the Foxp3 gene. In addition, treatment of SJL and BALB/c mice with the dual APL up-regulates Fas, FasL, and caspase 8, which leads to AICD. The up-regulated JNK activity in the dual APL-treated mice supports the presence of apoptotic downstream signaling.

We demonstrate here that treatment of SJL and BALB/c mice with the dual APL resulted in elevated levels of the CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory cells that are characterized by the CTLA-4, TGF-β, and Foxp3 markers. Most of the reports on CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells are of studies that were performed with naïve animals. Nevertheless, recently a growing number of studies demonstrated that these cells can be induced as well (18–21). Furthermore, purified antigen-specific regulatory T cells could be expanded and suppress effector T cell functions both in vitro and in vivo (21). The CD4+CD25+ cells share characteristics with the naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells, as determined by similarities in the phenotypes and function of these cells (e.g., CTLA-4 and Foxp3 up-regulation). The dual APL up-regulated the CD4+CD25+ cells in association with the up-regulation of CTLA-4 on these cells, as well as of other markers (such as TGF-β) and of Foxp3 (Figs. 3 and 4). Importantly, unlike immunoregulatory T cell markers such as CD25+, glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor, and CTLA-4, Foxp3 transcription has not been found to be induced in conventional CD4+CD25– T cells upon T cell receptor stimulation, indicating that Foxp3 expression is not a mere consequence of T cell activation (22, 23). The finding that peripheral CD4+CD25– T cells can be fully converted toward immunoregulatory T cells upon Foxp3 transduction indicates that peripheral naïve T cells are not intrinsically refractory to induction of immunoregulatory T cell activities (24). Moreover, a recent report demonstrated that peripheral CD4+CD25– T cells that were stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies in the presence of TGF-β acquired Foxp3 expression and regulatory function (24).

CTLA-4, which is up-regulated by the dual APL, has been reported to induce TGF-β production, an event that may account for aspects of CTLA-4 negative regulation (25).

TGF-β is a cytokine with known suppressor functions and involvement in the regulation of growth inhibition, apoptosis, and differentiation of multiple cell types (26–28). The immunosuppressive effects of the dual APL were shown to correlate with the up-regulated secretion of TGF-β. Moreover, anti-TGF-β neutralizing antibodies abrogated the inhibitory effects of the dual APL, supporting the important role of this cytokine in the inhibitory effects of the dual APL (9). TGF-β has been demonstrated in the present study to be up-regulated in CD4+CD25+ T cells after treatment with the dual APL (Fig. 4). In a previous study we demonstrated that, after treatment with the dual APL, there was an up-regulated secretion of TGF-β that was abolished when CD4+CD25+ T cells were depleted (10). In agreement, it has been reported that anti-TGF-β antibody can reverse the suppression by CD4+CD25+ T cells in a dose-dependent manner (14, 29). A key to understanding the cell contact-dependent immunosuppression by the suppressor T cells was the recognition that these cells express surface membrane-bound TGF-β (29). Whether contact-inhibited by CD4+CD25+ T cells that express surface-bound TGF-β or inhibited by the secreted TGF-β from these immunoregulatory T cells, neighboring T cell activity is suppressed by TGF-β. One of the pathways by which TGF-β transmits its downstream signals is the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4/JNK signaling pathway, which was reported to enhance the activity of Jun and ATF2 transcription factors, which may cooperate with SMADs through direct physical contacts (15). Furthermore, SMADs have been reported to be phosphorylated by JNK (15).

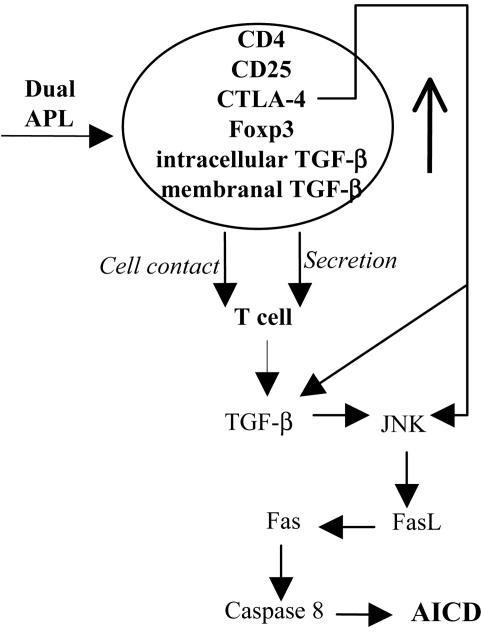

CTLA-4 ligation was found to up-regulate and sustain JNK activation (30). In the present study, JNK has been demonstrated to be up-regulated upon treatment with the dual APL, as determined in total LN cells and purified T cells (Fig. 5). It is possible that the less prominent effect observed in the purified T cells is due to a decline in the JNK signals that occurs during the purification procedure. In any case, the pJNK was up-regulated in purified T cells of both strains after treatment with the dual APL. Recent evidence indicates that JNK may commit T cells to stress-induced apoptosis through FasL expression (31, 32). Most importantly, AICD in T cells is significantly impaired in JNK1- and JNK2-deficient mice (33, 34), suggesting that JNK is actively involved in the regulation of AICD in primary T cells. Moreover, JNK activation was reported to require caspase 8 activity (16). Fas, which induces cell apoptosis by both activating a caspase cascade and altering mitochondria, is involved in switching off the immune responses and the cell-mediated cytotoxicity. In humans, genetic defects decreasing Fas function cause the autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, where autoimmunity is associated with accumulation of polyclonal lymphocytes in the secondary lymphoid tissues and expansion of T cells lacking both CD4 and CD8 (35). We report here that Fas, FasL, and caspase 8, which together take part in the Fas signaling pathway that leads to AICD, were up-regulated after treatment with the dual APL (Fig. 6). Based on the accumulating reported data and on the results presented in this study, we propose a cascade of events demonstrated in Fig. 7 that occurs in the presence of the dual APL and leads to the inhibition of autoreactive T cell function. Thus, treatment with the dual APL up-regulates the CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory cells that express CTLA-4 and Foxp3 transcription factors, as well as elevated levels of intracellular and membranal TGF-β. The CD4+CD25+ cells affect neighboring T cells through cell contact or by secretion of TGF-β to produce up-regulated levels of TGF-β to the intercellular space. The latter results in the elevation of JNK. JNK phosphorylates transcription factors that can activate the transcription of the FasL gene. When FasL is up-regulated, the Fas signaling pathway is enhanced, as determined by elevated caspase 8 levels, and T cells are subjected to apoptosis and inhibition of proliferation. Finally, although the similar results for the two mouse strains using two myasthenogenic peptides are of short-term experiments, we have previously shown that the dual APL was capable of ameliorating an established EAMG (6). The latter occurs most likely by means of a mechanism that is similar to the one proposed here.

Fig. 7.

The cascade of events leading to the down-regulating effect of the dual APL.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by DeveloGen (Rehovot, Israel), a drug discovery company focused on treatments for metabolic diseases.

Author contributions: H.B.-D. performed research; H.B.-D. analyzed data; H.B.-D. and E.M. wrote the paper; E.M. designed research; and M.S. was instrumental in the discussions.

Abbreviations: AChR, acetylcholine receptor; AICD, activation-induced cell death; APL, altered peptide ligand; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4; MG, myasthenia gravis; EAMG, experimental autoimmune MG; JNK, c-Jun-NH2-terminal kinase; LN, lymph node; FasL, Fas ligand; PE, phycoerythrin; CFA, complete Freund's adjuvant.

References

- 1.Lindstrom, J., Shelton, D. & Fuji, Y. (1988) Adv. Immunol. 42, 233–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drachman, D. B. (1994) N. Engl. J. Med. 25, 1797–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brocke, S., Brautbar, C., Steinman, L., Abramsky, O., Rothbard, J., Neumann, D., Fuchs, S. & Mozes, E. (1988) J. Clin. Invest. 82, 1894–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brocke, S., Dayan, M., Rothbard, J., Fuchs, S. & Mozes, E. (1990) Immunology 69, 495–500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz-Levy, Y., Paas-Rozner, M., Kirshner, S., Dayan, M., Zisman, E., Fridkin, M., Wirguin, I., Sela, M. & Mozes, E. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 3200–3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paas-Rozner, M., Dayan, M., Paas, Y., Changeux, J. P., Wirguin, I., Sela, M. & Mozes, E. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 2168–2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faber-Elman, A., Grabovsky, V., Dayan, M., Sela, M., Alon, R. & Mozes, E. (2000) Int. Immunol. 12, 1651–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faber-Elman, A., Grabovsky, V., Dayan, M., Sela, M., Alon, R. & Mozes, E. (2001) FASEB J. 15, 187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paas-Rozner, M., Sela, M. & Mozes, E. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12642–12647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paas-Rosner, M., Sela, M. & Mozes, E. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 6676–6681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakaguchi, S., Sakaguchi, N., Asano, M., Itoh, M. & Toda, M. (1995) J. Immunol. 155, 1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massimo, C. F., Cristoph, B., Giovanni, M., Francesco, P., Peter, R.-G. & Markus, F. N. (2004) J. Immunol. 5149–5153.15100250

- 13.Salomon, B., Lenschow, D. J., Rhee, L., Ashourian, N., Singh, B., Sharpe, A. & Bluestone, J. A. (2000) Immunity 12, 431–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, W. (2002) FASEB J. 16, 763–769. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massague, J. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 1, 169–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang, J., Gao, J. X., Salojin, K., Shao, Q., Grattan, M., Meagher, C., Laird, D. W. & Delovitch, T. L. (2000) J. Exp. Med. 191, 1017–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen, W. & Wahl, S. M. (2003) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 14, 85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiner, H. L. (2001) Immunol. Rev. 182, 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthias, G. H. & Leonard, C. H. (2003) Immunology 3, 223–232.12658270 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundstedt, A., O'Neill, E. J., Nicolson, K. S. & Wraith, D. C. (2003) J. Immunol. 170, 1240–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang, Q., Henriksen, K. J., Bi, M., Finger, E. B., Szot, G., Ye, J., Masteller, E. L., McDevitt, H., Bonyhadi, M. & Bluestone, J. A. (2004) J. Exp. Med. 199, 1455–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nomura, H. T., Sakaguchi, S. (2003) Science 299, 1057–1061.12522256 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hori, S. & Sakaguchi, S. (2004) Microbes Infect. J. 6, 745–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen, W., Jin, W., Hardegan, N., Lei, K. J., Li, L., Marinos, N., McGrady, G. & Wahl, S. M. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 198, 1875–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen, W., Jin, W. & Wahl, S. M. (1998) J. Exp. Med. 188, 1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sporn, M. B. (1999) Microbes Infect. J. 1, 1251–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen, W. & Wahl, S. M. (2002) Curr. Directions Autoimmun. 5, 62–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorelik, L. & Flavell, R. A. (2002) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakamura, K., Kitani, A. & Strober, W. (2001) J. Exp. Med. 194, 629–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider, H., Mandelbrot, D. A., Greenwald, R. J., Ng, F., Lechler, R., Sharpe, A. H. & Rudd, C. E. (2002) J. Immunol. 169, 3475–3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faris, M., Latinis, K. M., Kempiak, S. J., Koretzky, G. A. & Nel, A. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 5414–5424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kasibhatla, S. T., Brunner, L., Genestier, F., Echeverri, A., Mahboubi, D. R. & Green, M. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 1, 543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dong, C., Yang, D. D., Wysk, M., Whitmarsh, A. J., Davis, R. J. & Flavell, R. A. (1998) Science 282, 2092–2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sabapathy, K., Hu, Y., Kallunki, T., Schreiber, M., David, J. P., Jochum, W., Wagner, E. F. & Karin, M. (1999) Curr. Biol. 11, 116–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dianzani, U., Chiocchetti, A. & Ramenghi, U. (2003) Life Sciences J. 72, 2803–2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]