Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

The objective of this study is to evaluate the clinical efficacies of open versus endoscopic surgery in the treatment of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) and investigate the feasibility and safety of endoscopic surgery as an alternative to open surgery in these cases.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

A retrospective analysis was performed from June 2002 to February 2014. A total of 59 cases were attempted. The neonates were divided into either an endoscopic or open surgery group. The pre-, intra- and post-operative data on the neonates were analysed, and the surgery-related complications, survival rates and recurrence rates were compared between the two groups.

RESULTS:

Demographic characteristics were not significantly different between the two groups. Compared with open group, the hospital stay and post-operative mechanical ventilation time were significantly shorter, while surgery duration was significantly longer in the endoscopic surgery group. The recurrence rate was higher and the survival rate was lower in the endoscopic surgery group with no statistically significant and the recurrence rate has decreased over the past 5 years.

CONCLUSIONS:

We have demonstrated that the endoscopic surgery is safe and effective for repairing CDH. The endoscopic surgery is a minimally invasive procedure with fast post-operative recovery and a good cosmetic outcome.

Keywords: Diaphragmatic hernia, endoscopic surgery, laparoscope, neonate

INTRODUCTION

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a congenital disease that results in a series of pathophysiological changes and is results when the abdominal organs herniate into the chest cavity in patients with unilateral or bilateral defects in the diaphragm. Other defects, including cardiac and pulmonary hypoplasia, are also commonly found in the patients with CDH.

CDH is one of the most critical illnesses addressed in neonatal surgeries worldwide. The aetiologies and pathogeneses of CDH are still unclear, but the incidence rate is approximately 1:2500–1:5000.[1] Although the efficacies from the treatment of CDH have increased in recent years, debates are ongoing regarding which surgical methods to use – open surgery or endoscopic surgery – for this disease.[2] Here, we analysed the clinical data on CDH patients treated between June 2002 and February 2014, compared the effects of open versus endoscopic surgery on recovery and outcome, and explored the clinical efficacies and safety profiles of endoscopic surgery in treating CDH.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Clinical data

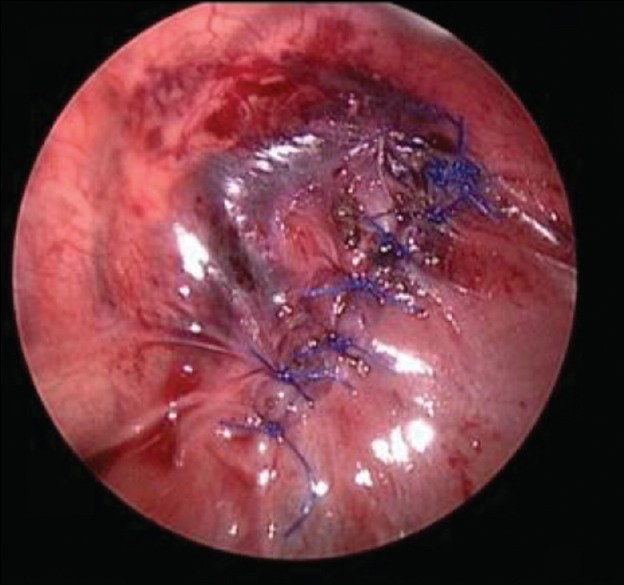

From June 2002 to February 2014, 64 neonatal CDH neonatal patients were treated at our hospital (The capital institute of pediatrics, Beijing). All patients were <30 days old. Three patients refused treatment, and the patients were discharged without further medical advice. Two patients, including one who underwent thoracoscopic and one who underwent laparoscopic surgery, converted to open surgery because of the relatively large defects of their diaphragms. These five cases were not included in the present study. All 59 remaining patients underwent surgery and were categorised into either endoscopic surgery (n = 19) or open surgery (n = 40) groups according to the surgical method. Among the 19 patients in the endoscopic surgery group, 10 underwent thoracoscopic surgery and 9 underwent laparoscopic surgery. Of the 59 patients, 26 were boys; the mean age of the 59 patients was 3.8 ± 0.3 days at the time of surgery. Fifty-two patients had CDH on the left side, and 7 had CDH on the right side. The mean gestational age of these patients was 38.6 ± 0.3 weeks, and the mean body weight was 3.4 ± 0.2 kg at the birth. Thirty-two patients were prenatally diagnosed with CDH, and tracheal intubation was performed on all of them immediately after birth; all were then transferred to our hospital. The remaining patients had symptoms after the birth of mainly shortness of breath and wheezing. The mean Apgar score of these patients was 6.3 ± 0.4 at 1.0 min after birth and 8.2 ± 0.3 at 5.0 min after birth. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all patients. The general characteristics of the patients were not significantly different between the two groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 59 neonates undergoing congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair

Pre-operative examination

A gastric tube was used on each patient before surgery and CDH was confirmed by chest X-ray. Computed tomography scanning was also performed for patients who could not be diagnosed using chest X-ray. The conditions of the organs in the thoracic cavity were also determined by imaging. Echocardiography was performed before surgery to evaluate cardiac function and identify any pulmonary hypertension and cardiac defects.

Treatment methods

All effort was made to correct any electrolyte and acid-base imbalances, control any pulmonary infection and improve the nutritional status of all patients before surgery. After all patients fasted for the appropriate amount of time before surgery, a gastric tube was inserted and intestinal lavage was performed. Either open surgery or endoscopic surgery was performed on the patients as follows.

Open surgery

The thoracic cavity of the neonates who underwent open surgery was accessed by thoracic or abdominal incision. The hernial contents were placed in the normal position, the defects of the diaphragm were completely exposed, and an interrupted mattress suture was performed at the margins of the defects. In neonates having a hernial sac, the sac was removed and a drainage tube was retained, if necessary.

Endoscopic surgery

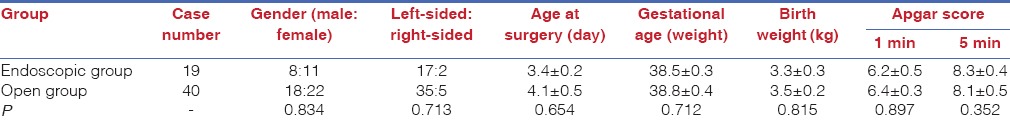

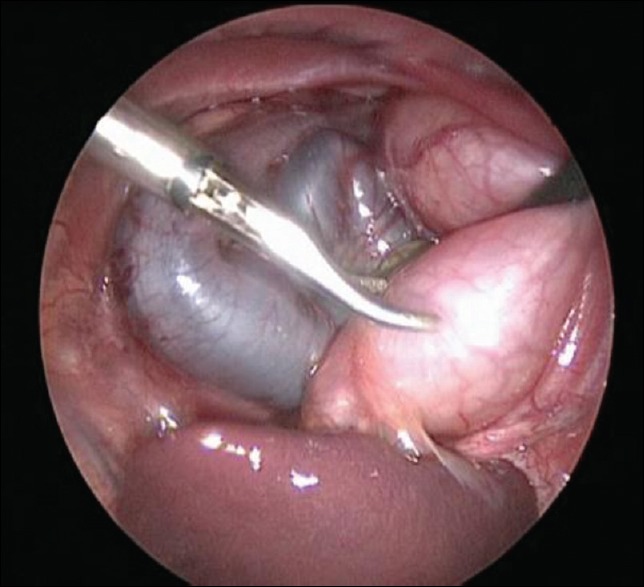

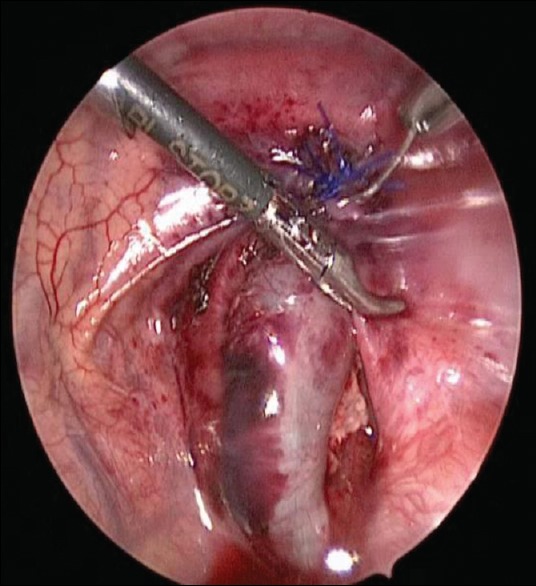

The neonates who underwent thoracoscopic surgery were placed in a lateral position, given general anaesthesia and intubated. Standard sterility protocols were used to disinfect and drape the surgery and surrounding areas. A trocar was inserted at the intersection between the median axillary line and fifth intercostal, anterior axillary line and sixth intercostal and posterior axillary line and sixth intercostal. After the surgery platform was established, the hernia contents were placed in the normal position in the abdominal cavity using forceps with the assistance of pneumothorax [Figure 1]. The defects of the diaphragm were exposed and observed. The peritoneum at the margin of the hernial sac was incised by electrocautery to expose the muscle tissues. An interrupted suture using 2–0 Prolene thread was used to close the diaphragmatic hiatus from the interior to the exterior along the longitudinal axis (left–right direction) of the hernial ring [Figure 2]. The forceps were then removed, and the incisions were closed [Figure 3]. After recovering from anaesthesia, the tracheal tube was removed after the disease was stable.

Figure 1.

Hernia contents

Figure 2.

The lateral suture diaphragm

Figure 3.

Consequence of suture

The patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery were placed in a dorsal-elevated position, given general anaesthesia and intubated. A trocar was inserted through the umbilicus, left upper quadrant of the abdomen and the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. Surgical forceps were placed through the trocas and the type, position, severity and complications of the diaphragm defects were observed. The round liver ligament, falciform ligament, coronary ligament and deltoid ligament were resected to sufficiently expose the affected diaphragm. Atraumatic forceps were used to place the hernial contents (such as spleen and intestine) back into the abdominal cavity, and scissors were used to cut the peritoneum at the internal layer of the hernial sac at the sac neck, after which it was separated and resected. A needle with 2–0 thread inserted through the abdominal wall into the abdominal cavity, leaving part of the thread outside the abdominal cavity to help with traction after the incisions were closed. Either continuous full-layer suturing or interrupted suturing was performed from left anterior to right posterior for the diaphragmatic hiatus, with 0.8 cm between the sutures; no closed thoracic drainage was used. After the neonate recovered from anaesthesia, the tracheal tube was removed after the disease was stable. All neonates were on routine mechanical ventilation after surgery. Adjuvant therapies, including fluid infusion, oxygen and anti-infection medication, were applied, and food intake was allowed after the intestinal functions had recovered.

Follow-up

All the patients were followed up in the outpatient department at 1.0, 3.0, 6.0 and 12 months after surgery every 6.0 months. Clinical data of age at the surgery, surgery duration, hospital stay and complications were analysed.

Statistical analyses

SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Incorporated, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analyses. Quantitative data were compared using the t-test or rank-sum test, and qualitative data were compared using the Chi-squared test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Surgical data and complications

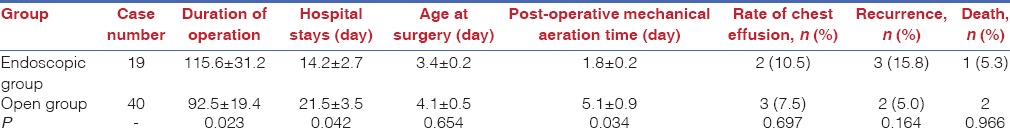

Data comprising surgery duration, incidence of pleural effusion, duration of hospital stay and post-operative mechanical ventilation time were compared between the two groups. The mean surgery duration was significantly longer in the endoscopic surgery group than in the open surgery group (115.6 ± 31.2 vs. 92.5 ± 19.4 min, respectively; P < 0.05). The mean hospital stay (14.2 ± 2.7 vs. 21.5 ± 3.5 days, respectively; P = 0.042) and post-operative mechanical ventilation time (1.8 ± 0.2 vs. 5.1 ± 0.9 days, respectively; P = 0.034) was significantly shorter in the endoscopic surgery group than in the open surgery group. The post-operative 24-h PCO2 (47.8 ± 1.8 vs. 48.6 ± 1.5 mmHg, respectively; P = 0.163) and incidence of pleural effusion (10.5 vs. 7.5%, respectively; P = 0.697) was not significantly different between the two groups [Table 2]. All patients were followed up for 1.0–140 months, and the growth and development of each were similar to that of neonates of the same age.

Table 2.

Post-operative charactoeristics

Survival and recurrence rates

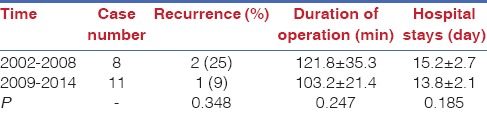

Among the 59 patients, 3 died after surgery, yielding an overall survival rate of 94.9% (56/69). Among the 19 patients who underwent endoscopic surgery, 1 died after surgery, yielding a survival rate of 94.7% (18/19); among the 40 patients who underwent open surgery, 2 died after surgery, yielding a survival rate of 95.0% (38/40). The survival rate was not significantly different between the two groups (P > 0.05). The overall recurrence rate in the patients was 8.5% (5/59) in the present study. The recurrence rate in the endoscopic surgery group (15.8%, 3/19) was higher than that in the open surgery group (5.0%, 2/40), but the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Current recurrent rates (9 vs. 25%, respectively; P = 0.348), surgery duration (103.2 ± 21.4 vs. 121.8 ± 35.3 min, respectively; P = 0.247) and hospital stay (13.8 ± 2.1 vs. 15.2 ± 2.7 days, respectively; P = 0.185) decreased within the past 5 years compared with those of previous procedures, but the differences were not statistically significant [Table 3]. In addition, the hospital stay (13.8 ± 2.1 vs. 21.5 ± 3.5 days, respectively; P = 0.039) was shorter, the surgery duration (103.2 ± 21.4 vs. 92.5 ± 19.4 min, respectively; P = 0.046) was longer, and the recurrence rate (9.0 vs. 5.0%, respectively; P = 0.327) was higher in the patients who underwent endoscopic surgery within the past 5 years compared with those of the open surgery group, but the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes of 2002-2008 versus 2009-2014

DISCUSSION

The surgical spaces are generally small in neonates and there is a high risk of damaging surrounding vital organs when performing these procedures. In addition, neonates cannot tolerate pneumoperitoneum well; therefore, it is very diffiult to perform endoscopic diaphragmatic hernia-repairing surgery on these patients. Since the first case of using minimally invasive surgery to repair neonatal CDH was reported in 2003,[3] doctors at more and more centres[4,5] have performed endoscopic surgery to treat the condition. The present study compared the clinical efficacies of endoscopic versus open surgery in treating neonatal CDH, and found that although using endoscopic surgery to repair the hernia involved a relatively longer operation, the hospital stay was significantly shorter than that after open surgery. Although the recurrence rate after endoscopic surgery was higher than that after open surgery, the difference was not significant. Endoscopic surgery has several advantages, such as minimal invasion, fast post-operative recovery and good cosmetic outcome.

The diagnosis of CDH mainly relies on prenatal ultrasound examinations, postnatal symptoms and X-ray imaging.[6] Previous studies have shown that ~60% of CDH cases can be diagnosed using prenatal ultrasound examinations.[7] The diagnosis of CDH before birth can help pregnant women choose the methods and sites for delivery of their babies, and help guide the rapid transfer of the neonates to the neonatal surgical centre for further treatment. In the present study, 54.2% (32/59) of the cases were prenatally diagnosed, which was similar to levels reported in previous studies.

Currently, the surgical methods for the treatment of CDH comprise open surgery (thoracotomy and laparotomy) and endoscopic surgery (laparoscopy and thoracoscopy). The open surgery mainly uses the transabdominal approach, although some might also use the transthoracic approach. Using the transabdominal approach could well expose the defects at the posterior wall of the diaphragm, which could facilitate suturing and help treat the complicated gastrointestinal anomalies. The transthoracic approach can better expose the defects of the diaphragm after the hernial contents are put back into the abdominal cavity, and thus the repair can be more easily performed.[8] The most important advantages of endoscopic surgery are that it is minimally invasive and post-operative recovery is rapid. In recent years, several studies have shown that improved surgeon skills, advances in equipment, gains in experience and improved cooperation among staff has reduced the duration of endoscopic surgery, the incidence of excessive intraoperative bleeding, the length of time for post-operative recovery.[9] A multicentre study in Europe showed that the rate of conversion to open surgery was higher in those who underwent laparoscopic surgery than in those who underwent thoracoscopic surgery to repair CDH;[10] however, the rate of conversion to open surgery was not statistically different among the subgroups who underwent different types of endoscopic surgeries, and thus the operators could choose the suitable surgical method according to the disease conditions and their own experience and preferences.

With the advancement and widespread application of endoscopic technology, the differences in the outcomes between endoscopic and open surgeries have been observed more and more. Most studies that compared the efficacies between these two surgical methods focused mainly on the following two aspects:

Effects of CO2

Previous studies[11] have shown that compared with open surgery, the CO2 used in endoscopic surgery can induce a significant increase in pulmonary artery pressure in neonates and subsequently increase the mortality rate; therefore, medical staff should be very careful when choosing endoscopic surgery to treat neonatal CDH. Neonates might be more sensitive to CO2 than older children; therefore, they should be placed in a dorsal elevated position to allow the liver, spleen and intestines to fall naturally so that the regions below the diaphragm can be clearly observed with relatively low-pressure pneumoperitoneum, which would reduce the risks from using CO2. We speculated that the pneumoperitoneum pressure during surgery should be relatively low and maintained at a level just high enough to allow the operators to correctly evaluate the development of the diaphragm and suture accordingly. The operators should also press the abdomen gently after surgery to help completely expel CO2 before the trocars are removed to reduce CO2 absorption, which is very important for restoration of gastrointestinal functions and to reduce the risk of abdominal discomfort. In addition, the neonates should be kept warm during surgery and efforts should be made to prevent the development of scleredema after surgery.

Recurrence rate

Compared with the open surgery group, the recurrence rate in the endoscopic surgery group was higher, which is considered to be one of the disadvantages of the latter. Previous studies have shown that the recurrence rate after thoracoscopic surgery is ~5.0%–25%.[12] In a retrospective study by Lansdale et al.,[13] the results showed that the recurrence rate was significantly higher in those who undergo endoscopic surgeries than in those who undergo open surgeries (7.9 vs. 2.7%, respectively; P < 0.05). Gander et al.[14] also compared the clinical efficacies between thoracoscopic and open CDH repair and found that the recurrence rate in the thoracoscopic surgery group was significantly higher than that in the open surgery group. In the present study, we also found that the recurrence rate in the endoscopic surgery group was higher than that in the open surgery group (15.8 vs. 5%, respectively; P > 0.05), but the difference was not statistically significant. We further compared the recurrence rate after endoscopic surgery between CDH repair over the recent 5 years and all neonates, and found that the recurrence rate in the recent 5 years had decreased, but the difference was not statistically significant (9.0 vs. 15.8%, respectively; P > 0.05). In addition, we found that surgery duration and duration of hospital stay in the recent 5 years also decreased. We speculated that the relatively high recurrence rate in the endoscopic surgery group could be associated with the fact that suturing diaphragm defects is very difficult and could result in insufficient separation of the posterior margin of the diaphragm, or the high tension during the suturing. Both the recurrence rate and surgery duration decreased with the gain in experience and an increase in surgical skills although the treatment efficacies are comparable with those of the open surgery group.

Study limitations

As a retrospective study, the perioperative treatments for neonates in the two groups were different; therefore, randomised controlled trials using larger sample sizes are necessary to further compare the efficacies between endoscopic and open surgeries in repairing diaphragm defects, and evaluate whether endoscopic surgery could be the preferred method by which to treat CDH.

CONCLUSIONS

This study showed that endoscopic repair of CDH is safe and effective, and the clinical efficacies are comparable with those of open surgery. With the application of the endoscopy technology and a gain in surgical skills, endoscopic repairs of diaphragm defects could be the preferred method by which to treat CDH.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank those patients who supported our study and authors who provided us with the full-text.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Buys Roessingh AS, Dinh-Xuan AT. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: Current status and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:393–406. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0904-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badillo A, Gingalewski C. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: Treatment and outcomes. Semin Perinatol. 2014;38:92–6. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arca MJ, Barnhart DC, Lelli JL, Jr, Greenfeld J, Harmon CM, Hirschl RB, et al. Early experience with minimally invasive repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernias: Results and lessons learned. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1563–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(03)00564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang EY, Allmendinger N, Johnson SM, Chen C, Wilson JM, Fishman SJ. Neonatal thoracoscopic repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: Selection criteria for successful outcome. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1369–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shalaby R, Gabr K, Al-Saied G, Ibrahem M, Shams AM, Dorgham A, et al. Thoracoscopic repair of diaphragmatic hernia in neonates and children: A new simplified technique. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24:543–7. doi: 10.1007/s00383-008-2128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedrick HL. Management of prenatally diagnosed congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2013;22:37–43. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruano R, Takashi E, da Silva MM, Campos JA, Tannuri U, Zugaib M. Prediction and probability of neonatal outcome in isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia using multiple ultrasound parameters. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:42–9. doi: 10.1002/uog.10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka T, Okazaki T, Fukatsu Y, Okawada M, Koga H, Miyano G, et al. Surgical intervention for congenital diaphragmatic hernia: Open versus thoracoscopic surgery. Pediatr Surg Int. 2013;29:1183–6. doi: 10.1007/s00383-013-3382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nam SH, Cho MJ, Kim DY, Kim SC. Shifting from laparotomy to thoracoscopic repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in neonates: Early experience. World J Surg. 2013;37:2711–6. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomes Ferreira C, Reinberg O, Becmeur F, Allal H, De Lagausie P, Lardy H, et al. Neonatal minimally invasive surgery for congenital diaphragmatic hernias: A multicenter study using thoracoscopy or laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1650–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0334-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liem NT. Thoracoscopic approach in management of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatr Surg Int. 2013;29:1061–4. doi: 10.1007/s00383-013-3394-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho SD, Krishnaswami S, Mckee JC, Zallen G, Silen ML, Bliss DW. Analysis of 29 consecutive thoracoscopic repairs of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in neonates compared to historical controls. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:80–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lansdale N, Alam S, Losty PD, Jesudason EC. Neonatal endosurgical congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2010;252:20–6. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181dca0e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gander JW, Fisher JC, Gross ER, Reichstein AR, Cowles RA, Aspelund G, et al. Early recurrence of congenital diaphragmatic hernia is higher after thoracoscopic than open repair: A single institutional study. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:1303–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]