Abstract

Objectives

To explore the perceptions of palliative care (PC) needs in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and their caregivers.

Background

IPF carries a poor prognosis with most patients succumbing to their illness at a rate comparable to aggressive cancers. No prior studies have comprehensively explored perceptions of PC needs from those currently living with the disease, caring for someone living with the disease, and who cared for a deceased family member.

Methods

Thematic analysis of focus group content was obtained from thirteen participants.

Results

Four themes described frustration with the diagnostic process and education received, overwhelming symptom burden, hesitance to engage in advance care planning, and comfort in receiving care from pulmonary specialty center because of resources.

Conclusions

Findings support that patients and caregivers have informational needs and high symptom burden, but limited understanding of the potential benefits of PC. Future studies are needed to identify optimal ways to introduce early PC.

Keywords: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Caregivers, Palliative care, Symptom burden, Advance care planning

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive fibro-proliferative lung disease that affects approximately 128,000 individuals in the US annually.1 The prognosis of IPF is poor, with most patients succumbing to their illness at a rate comparable to aggressive cancers.2 Median survival from diagnosis is 3.8 years; however, patients may succumb to a rapid death within 6 months.3,4 Although transplantation is an effective surgical therapy,5,6 less than 20% of patients ever receive a lung transplant.4 The remaining 80% have few treatment options. As fibrosis advances and lung function deteriorates, patients experience a progressive increase in shortness of breath, cough and fatigue. These symptoms are distressing to patients and family caregivers and present a challenge in maintaining quality of life as the disease relentlessly progresses.7,8 Despite the fatal prognosis, patients and caregivers often fail to understand the poor prognosis.9

An extensive literature review supports that discussion of palliative care by clinicians who manage the care of patients with advanced lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, occurs less frequently than for other life-limiting conditions, such as cancer.9–12 Patients with IPF represent a group of individuals with a chronic respiratory disease who are without disease-reversing treatment options and, absent lung transplantation, inevitably face progressive decline and death.1 Prior work supports that location of death too frequently occurs in an acute care setting, without the benefit of support available through advance care planning including the introduction of palliative care.13–15 Prior studies have detailed the impact of IPF on quality of life,16 advocated for early introduction of palliative care as a means to reduce symptom burden,10,13,17 and explored patient perceptions of needs.18 However, no prior studies have explored patient/family caregiver perceptions of palliative care needs from the viewpoint of those currently living with the disease, caring for someone living with the disease, and who cared for a deceased family member.

The aim of this study was to explore the perceptions of patients with IPF and their family caregivers regarding their learning and supportive care needs, frequency of conversations about advance care planning, and familiarity with palliative care. Findings from this study will provide preliminary information about potential barriers and means to address these from the patient/family caregiver perspective.

Methods

Design

Thematic analysis19,20 of focus group content obtained from interviews with patients with IPF and their family caregivers.

Setting

The University of Pittsburgh Dorothy P. and Richard P. Simmons Center for Interstitial Lung Disease at UPMC, a multidisciplinary center devoted to research and treatment of interstitial lung disease with a focus on IPF. The University of Pittsburgh Dorothy P. and Richard P. Simmons Center for Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD) at UPMC, setting for this study, was established in 2001 as a multidisciplinary center devoted to research and treatment of interstitial lung disease with a focus on IPF. The Simmons Center for ILD is one of forty designated Care Centers in the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation Care Center Network. Care Centers are dedicated to improving the clinical care of those living with pulmonary fibrosis and utilize a best practices model to achieve this goal. http://www.pulmonaryfibrosis.org/medical-community/pff-care-center-network. The Center evaluates over 15–20 new patients with ILD monthly; of those 6–10 have a newly confirmed diagnosis of IPF. The center has seen more than 4500 patients with interstitial lung disease (>1000 with IPF). UPMC is also an internationally recognized transplant center with an annual range of 68–109 lung transplants over the past 5 years (2010–2015). Although transplantation is an effective surgical therapy,5,6 we reported that 43% of our patients at our center were referred for lung transplant evaluation, but only 13% of patients ever receive a lung transplant due to several factors including later referral, appropriate candidacy, and disease course variability.4

Participants

Participants were a convenience sample of patients and family caregivers recruited between November 2014 and February 2015 from our IPF clinic and support group. Because perceptions may differ in those currently living with the disease, those caring for these individuals, and those who lost a family member to the disease, participants were assigned to one of three groups, defined by their role. Groups were stratified by participant role to capitalize upon shared identity within groups. Based on literature identifying appropriate group size, the target enrollment was 3–5 participants per group (Table 1). The groups consisted of: (1) current patients with IPF (n = 5); (2) family caregivers of current patients (n = 5); and (3) family caregivers of decedent IPF patients (n = 3). Potentially eligible patients and family caregivers were identified during clinic visits and support group meetings and informed about the study, its risks and benefits; we obtained written informed consent from participants. Participants were provided with lunch and parking vouchers. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (PRO14090433) approved the study.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical information.

| Participant | Age | M/F | CG relationship | Since Dx (yrs) | Most recent FVC% | Most recent DLCO% | Oxygen | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P | 68 | M | 3 | 125 | 26 | Y | |

| 2 | P | 69 | M | 1 | 81 | 70 | Y | |

| 3 | P | 85 | M | 9 | 98 | 63 | Y | |

| 4 | P | 71 | M | 11 | 65 | 50 | N | |

| 5 | P | 64 | M | 4 | 66 | 67 | N | |

| 6 | CG | F | S | |||||

| 7 | CG | F | S | |||||

| 8 | CG | F | D | |||||

| 9 | CG | F | S | |||||

| 10 | CG | F | S | |||||

| 11 | CG (D) | F | S | |||||

| 12 | CG (D) | F | D | |||||

| 13 | CG (D) | M | S |

P, patient; CG, caregiver; D, decedent; S, spouse; D, daughter; FVC, forced vital capacity; DLCO, diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; O2, supplemental oxygen.

Data collection

Focus groups were conducted in a private conference room by facilitators; both of whom are experienced qualitative researchers, and have previous experience in facilitating focus groups regarding palliative care content: [Nurse faculty (MRQ) and palliative care PhD prepared researcher (DK)]. They had no direct or indirect involvement with patient care of these research participants to maintain objectivity. There were four note takers; the note takers were one palliative care nurse practitioner, one PhD nursing student and two research coordinators from the Simmons Center. We chose focus groups (as opposed to individual interviews), given that this methodology allows for participants to describe their experiences in an environment that promotes reflection and synergy with other participants, resulting in a shared voice that represents the experiences of several individuals with a common characteristic (i.e., a diagnosis of IPF).21 Participants were asked to introduce themselves and respond to the Focus Group Guide that served as opened ended prompts to promote discussion (Table 2). The focus group guide was developed by the authors (KOL, MQR, and DK) following a review of the literature to identify evidence gaps regarding knowledge, attitudes, and preferences advance care planning and palliative care in individuals with serious pulmonary disease. Each session lasted approximately 1.5 h. Comments were recorded on a digital tape recorder and transcribed to an encrypted flash drive.

Table 2.

Focus group guide.

|

Data analysis

A thematic analysis conducted by experienced qualitative analysts at the University of Pittsburgh Quality Data Analysis Program (QDAP) was used to develop a codebook that identified major conceptual categories. Initially, two coders and the project manager read through two of the three focus group transcripts and independently identified the major concepts. The codebooks were then consolidated into a single codebook by the project manager. Using ATLAS.ti 7, a qualitative data analysis software program that enables multi-coder projects, the two coders then independently applied these codes to the third, remaining transcript as a means of testing the codebook. Following discussion of the results, the QDAP project manager modified the codebook to clarify code names and their respective definitions. The coders then tested this modification against transcripts used for initial codebook development. This modification minimized disagreement, the initial coding was revised and ATLAS.ti 7 was used to generate a list of quotations for each individual code in the codebook.

Results

Patient participants were exclusively male (100%), white (100%) and aged 71.4 ± 7.2 years (Table 1). Time since diagnosis of IPF ranged from 1 to 11 years. Family caregivers were primarily female (87.5%), white (100%), and the spouse of a patient (75%). Time since death of the patient ranged from 35 to 66 months.

Interview themes

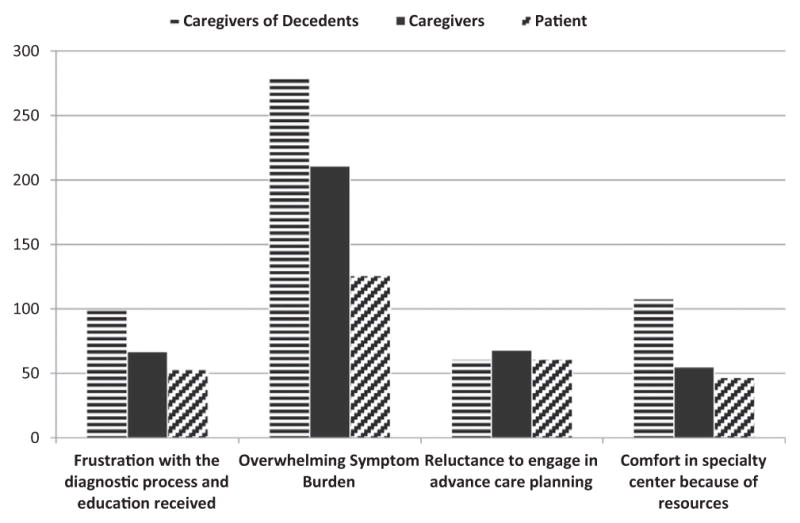

We identified several themes: (1) frustration with the diagnostic process and education received, (2) overwhelming symptom burden, (3) reluctance to engage in advance care planning, and (4) comfort in the specialty center because of resources. We captured the different perspectives of the patient, caregiver, and caregiver of the decedents during the focus groups. Fig. 1 illustrates the number of times that the theme was mentioned by the particular group.

Fig. 1.

Number of times theme was referenced in focus groups by group.

Theme 1: Frustration with the diagnostic process and education received

Patients and caregivers expressed frustration with limited knowledge of the disease within their communities. It was interesting to see that the caregivers of decedents shared their frustration with the diagnostic process and education received more than patients and caregivers of patients still alive (Fig. 1). They described challenges finding answers to explain their symptoms and delay in referral to a specialty center. As related by one patient:

“…my primary care physician kept hearing that crackling in my lungs. So we took an x-ray that first year at my annual physical. A year later, another physical, he says, “Oh, I still hear that crackling. I don’t like that. Let’s get an x-ray.” So we took another x-ray. Initially he thought that perhaps I had some kind of scarring from pneumonia, but the second year, second annual physical, we went to a pulmonologist – and he requested that I do the biopsy…”

A caregiver of a deceased patient related:

“When my wife first found out it, she kept coughing and I kept telling her to go to the MD. She had a biopsy and the report said IPF. I “googled” it and what I read wasn’t what I wanted to read. We asked if we could go to the specialty center and were told that she wasn’t sick enough. She died the next month.”

Even when presented with a description of their disease, patients were challenged to understand its implications:

One patient reported:

“I don’t understand it near as well, as I feel I need to. I was never sick my whole life, and up to just about two years ago. I started having problems and – short of breath, didn’t understand why, and not until my personal physician took an x-ray of my chest and he says, you need to go to a specialist.” … I don’t really totally understand what I have. I know what they tell me I got, but and they’ve explained a lot, but … I still don’t understand.”

Another patient reported:

“I was so relieved that it wasn’t lung cancer. I wasn’t sure what IPF was, but I thought it can’t be as bad as lung cancer.”

However, reactions differed among caregivers who verbalized understanding tempered by hope that consequences would be different. As one caregiver related:

“… We all understand. I think we’re all in denial. As far as I’m concerned, there’s nothing wrong with him, but that’s not true. And I’m just glad that he came out of that depression that he was in and comes to the meetings [Support Group] and everything, you know? So we all just do the best we can.”

Another caregiver related:

“And I saw a different side of my husband when this all happened, because I am in awe of the fact that he is just … took it all in, it was a little bit tough at first. And I wouldn’t say denial because if he were sitting here, he’d tell you “I want to know every gory detail. I want to know how to prepare myself, I want to understand it.” And he used that word, “gory detail.”

Theme 2: Overwhelming symptom burden

There was overwhelming symptom burden for patients and caregivers, both physical and psychological. Caregivers, especially those of decedents reported the most mentions of overwhelming symptom burden, greater than the patients. Cough was the most frequently mentioned symptom, affecting both the patient and the caregiver, as described by a caregiver of a deceased member:

“Coughing! Coughing! People would ask why didn’t you go to a different bedroom so you didn’t have to hear the cough, but I would feel bad, I couldn’t tell him. I was going to work on 2–3 hours of sleep.”

Another caregiver related:

“The coughing fits are so draining on him, he’ll be in the middle of something, start coughing and have to sit down and catch his breath.”

The need to use oxygen and its implications related to mobility, stigma, and convenience was also a major source of concern:

“Well, and that’s just like using oxygen, getting into a wheelchair, you know, the whole pride. It impacts that person’s identity and their version of what strength is. And so like resistance to using the oxygen or taking it out in public … oh, what a fight that was.”

Uncertainty around the terminal point of the disease’s progression seemed to magnify concern about symptoms. As one patient related:

“I was first told 50/50 chance of making five years … I guess just knowing how fast your air’s going to be gone when you get that point is. – Are you going to … what do we do? Do we just suffocate to death? I don’t know.”

Financial impact was also a major source of concern:

“The biggest thing for me has been the change … to lose out on being able to work … to be totally honest with you … the finances. I’ve been a worker all my life. Do I need to sell my home? It’s hard to see my wife take care of me.”

Another caregiver mentioned concerns about the cost of newly available medications:

“… If its $300 or $400 a month, they can’t get it lower – down to where I can afford that. I don’t have any – I don’t have the money to pay that kind of stuff.”

Theme 3: Reluctance to engage in palliative care and advance care planning

To explore perceptions, interview questions specifically asked patients and caregivers’ understanding of palliative care including advance care planning. Both patients and caregivers expressed hesitance to engage in advance care planning, also seen in Fig. 1:

“So the only preparation I’ve done has been financial to make sure that life insurance is up to date, the will’s done, that kind of stuff.”

Another patient related:

“As far as the will, I don’t have any kind of a will made up. We’ve talked about it. We – things as far as what you want done towards resuscitate, not resuscitate. We kinda talked about that.”

Another caregiver said:

“I’m afraid if we talk about the future, he will think that I know that he is going to die.”

There was confusion about the goals of palliative care and how this care option differenced from hospice. One caregiver said:

“Well, with hospice you’re going to die. Right soon, within six months, usually. That’s what I understand. And palliative is just to help make you be comfortable. But we know that you die with this disease, so what is the difference? Is it a longer time you can be on palliative care? Or people help you deal with the disease? I don’t know. I’m just guessing.

A caregiver of a patient became upset with the palliative care question:

“… I didn’t know this [focus group] had anything to do with palliative care, and I do have a problem focusing on the fatality.” [rolled seat back away from group] in answer to your question, YES I would rather focus on the positive. You hear its terminal once; you don’t need to hear it again. So …if there are positives, you focus on that. The fact that you hear there’s research and new treatment, even if we’re not a candidate, is really important. It really is about [looks into the distance] … how do I just … [quiet] you want to keep on.”

However, patients also voiced appreciation of education focused on best approaches to living with IPF:

“I kind of get a feeling that even just coming to support group is part of palliative care because we’re learning every aspect of the body and how to live better and they talk about how to get through this.”

Theme 4: Comfort in specialty center because of resources

Patients and caregivers noted a number of benefits to being part of a specialty center. They felt that their concerns were being addressed by physicians who were truthful about the future, but also provided positive encouragement. Caregivers of decedents reported the most comfort in specialty center during the focus group (Fig. 1). As one caregiver related:

“I think that the information here at this place is handed out differently than the information other places.”

Patients and caregivers especially appreciated the ability to participate in a support group.

“… [The support group] was a high priority in our lives because my husband was able to talk with other people who were suffering with what he was suffering with … They learned that they might be in a room with 30 people – this person has never had oxygen, this person has been oxygen since day one, you know, everybody’s case is different. So you know, you can’t say, ‘I have IPF and you don’t need oxygen.’ They learned why, you know, different people progress at different rates and you know … how the disease affects other people differently.”

Patients also commented positively on the ability to participate in research:

“I wanted to participate in research about this disease. I would like to have been able to go through more, but my age caught up with me, and I became too old to get into a research project.”

The availability of transplant was also valued even when patients experienced complications. As one caregiver of a deceased patients noted:

And on June 1st, they found lungs and flew them. My dad got another three years of quality life with his family and especially his grandkids.”

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study to explore patient/family caregiver perceptions of their needs from the viewpoint of current patients, current caregivers and caregivers of a deceased family member. Four major findings were present among all groups: (1) frustration with the diagnostic process and education received, (2) overwhelming symptom burden, (3) hesitance to engage in advance care planning, and (4) comfort in receiving care from pulmonary specialty center because of resources. As shown in Fig. 1, caregivers of decedents reported more mentions of 3 of the 4 themes (Frustration with diagnostic process and education received, overwhelming symptom burden, and comfort in specialty center) during the focus groups. This could be related to process of grief and closure or the desire to put their loved one’s illness and death in perspective, rather than spending time on the immediacy of the illness.

Although patients reported receiving information relating to the disease from their clinicians and the Internet, the first theme to emerge was that patients did not find that their informational needs were fully addressed. This perception was especially evident when symptoms first manifested. Later, after confirmation of the diagnosis, denial was common as noted by individual patient reflection on course of the disease. Because IPF often occurs in those “previously healthy” and symptoms resemble those of other lung diseases, patients with IPF may not realize the gravity of the diagnosis.22 Some patients seek second and third opinions.23 When told of their diagnosis, patients commonly express relief when they learn they do not have lung cancer. However, the two diagnoses have a very similar prognosis.24 Inability to establish the diagnosis may lead to a delay in seeking care at a specialty center. A delay of 2 years from onset of symptoms to a confirmed diagnosis and care at a specialty care center is common. This finding was initially reported in 2001,25 again in 2011,26 and more recently in 2015.13 The importance of evaluation at a specialty center relates to availability of resources including a support group, potential for research participation and evaluation for transplant. Sampson and colleagues reported that patients diagnosed with IPF were aware of their prognosis, but had little understanding of the different ways their disease might progress and be managed. Therefore, they continued to seek specific information about treatment options, symptom management and care at the end-of-life.27

The second theme that emerged was overwhelming symptom burden, with cough being a particularly debilitating symptom. Frustration with the need to use oxygen therapy and worry about finances and the cost of medications were additional concerns. In patients with IPF, the etiology of cough is unknown, but can be very bothersome to the patient and caregiver.28 A variety of therapies, including cough suppressants and opioids can be used to diminish this symptom. The effectiveness of these approaches varies, necessitating an approach tailored to the patient’s response.29 Supplemental oxygen may be beneficial, but comes with its own burden8 because of the equipment involved to provide the proper prescription. Provision of palliative care could be extremely helpful in this situation, as it could serve as a means to encourage patients to seek treatment for cough and use opioids or request prescription of these drugs for cough suppression. The need to use oxygen results from lung fibrosis, which limits gas exchange. Here also, palliative care could be extremely helpful, as the benefits of oxygen in enabling a more active life could be shared and efforts made to ensure the delivery system meets patient needs. Others have reported findings similar to ours from interviews conducted with patients and caregivers. Bajwah and colleagues interviewed 18 patients with IPF and their family caregivers and reported the profound impact of this disease both physically and psychologically.14 Belkin and colleagues conducted a study capturing caregiver perspectives on the effects of IPF and reported that caregivers experienced hardships throughout the disease course including dealing with the emotional issues as well as the physical limitations confounded by the demanding effects of use of supplemental oxygen.30

The third theme to emerge was hesitance to engage in advance care planning. Care planning was recognized as a need, but avoided because it was perceived as loss of hope. Caregivers of the patients living with the disease were vocal about only wanting positive options, including research opportunities. Patients appeared to lack understanding about the scope of support offered through palliative care, e.g., reducing symptom burden. In addition, there was confusion with hospice. Prior qualitative studies have reported that even when patients and caregivers understood the terminal nature of the disease, they did not appreciate that symptoms could escalate rapidly, resulting in death.27,31 Palliative care, in this situation, would be especially helpful as the need to consider options could be introduced over several meetings and patients could have symptom burden addressed and encouraged to discuss end-of-life planning. Onset of acute respiratory deterioration carries an extremely high morality in patients admitted to an intensive care unit.32,33 As found in other studies addressing patient wishes,18,34,35 palliative care would therefore seem particularly beneficial in addressing symptom burden and encouraging advance care planning. Notably, no randomized control trials have tested the benefits of early introduction of palliative care in this population. Findings were highly positive when this approach was tested in patients with advanced cancer in both inpatient and outpatient settings.36–38 Lack of evidence regarding benefits in this population may hinder patient acceptance and prompt clinicians to not advocate palliative care as an option.

The fourth theme to emerge was comfort in pulmonary specialty center care. Specialty center resources were valued in regard to support group participation, ability to participate in research studies, and the potential for transplantation. Patients and their caregivers found the specialist IPF clinic to be a trustworthy source of information. These centers promote a patient and caregiver centered, supportive approach coordinated by a multi-disciplinary team with an appropriate skill mix.27 With the lack of available treatment options, the ability to participate in clinical trials offers hope of personal benefit and giving to others. Support groups have been found to provide assistance in understanding disease management, decrease perceptions of symptom burden, and the ability to associate with patients and caregivers with similar needs.7

Palliative care has been successful in improving the quality of life of patients with lung cancer.36 IPF is a similar life-limiting lung disease but, as with other advanced lung diseases, our experience, and that of others, supports that referral to palliative care occurs infrequently and late.11–13,15 Progression of IPF may occur rapidly, at a slow but relatively consistent pace, or there can be long periods with no or limited progression.28 The unpredictable nature of the disease course makes it difficult for patients and family caregivers to appreciate that IPF is life limiting. However, inevitably, patients experience a decline in lung function that causes an increase in symptom burden (physical function, anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep quality, satisfaction with social role and pain), stress and negatively impacts quality of life.

Findings from this study provide new insights regarding patient and family caregiver understanding and preparedness. In the context of this disease, timing is viewed as a critical factor as acute exacerbation may result onset of acute respiratory failure, an outcome associated with extremely high mortality.32,33 Conversely, early introduction of palliative care may be interpreted by the patients and families as a sign of diminished hope. The challenge is to identify ways to operationalize and individualize palliative care and create models that best meet the needs of patients and family caregivers.

In contrast to settings involving patients with metastatic cancer where the benefits of palliative care are well established and accepted by patients and clinicians, exploration of reasons that explain late or infrequent referral in patients with IPF and other lung diseases is in its infancy. Brown and colleagues10 in an opinion essay identified five clinician-related barriers: (1) uncertainty regarding prognosis; (2) lack of knowledge and expertise; (3) concerns regarding prescription of opiates; (4) fear of diminishing hope; and (5) bias toward those whose lung disease is perceived to be smoking related. To overcome these barriers, they suggested palliative care be automatically initiated following diagnosis without consideration of disease severity. They also suggested policy or system based incentives or reminders to prompt initiation. While important, these initiatives do not address barriers from the patient/caregiver perspective identified in this study. There appeared to be great reluctance to accept initiatives that suggested a terminal diagnosis. In patients with cancer, changing the term palliative care to “supportive care” has been associated with better understanding and more favorable impressions and this approach might encourage greater willingness to accept this referral.39

Limitations

This study has several limitations. It was conducted in one center and is therefore reflective of its approach. All patients were male and Caucasian. All caregivers were Caucasian, predominantly female and spouses. Their perceptions may not be reflective of the general IPF population. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with prior studies that reported the negative effects and high symptom burden associated with IPF and limited understanding of the potential benefits of palliative care. An effort was made to recruit more participants, especially caregivers of decedents, but efforts to increase numbers proved unsuccessful. In addition, interviews were conducted at one point in time. It would be interesting to have been able to interview participants over time, to determine if their perceptions or needs change as they experience different levels of disease progression.

Conclusion

Extensive literature supports benefits of palliative care in patients with life-limiting illness. Our findings support that patients and family caregivers have informational needs and high symptom burden, but limited understanding of the potential benefits of palliative care. Both patients and caregivers valued referral to a specialty lung center because of the resources this offered, including the potential to participate in support group, research studies and evaluation for lung transplant. Future studies are needed to identify optimal ways to introduce this benefit to patients and family caregivers.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Leslie A. Hoffman Acute Care Endowed Research Award, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing. Dr. Kavalieratos receives research support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K12HS022989), the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (PILEWS14QI0), as well as a Junior Faculty Career Development Award from the National Palliative Care Research Center.

References

- 1.Raghu G, Collard H, Egan JJ, et al. ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(6):788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vancheri C, Failla M, Crimi N, Raghu G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a disease with similarities and links to cancer biology. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:496–504. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00077309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raghu G, Chen SY, Yeh WS, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older: incidence, prevalence, and survival, 2001–11. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(7):566–572. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richards TJ, Kaminski N, Baribaud F, et al. Peripheral blood proteins predict mortality in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(1):67–76. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0058OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez FJ, Safrin S, Weycker D, et al. The clinical course of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(12 Pt 1):963–967. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-12_part_1-200506210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panos RJ, Mortenson RL, Niccoli SA, King TE., Jr Clinical deterioration in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: causes and assessment. Am J Med. 1990;88(4):396–404. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90495-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindell KO, Olshansky E, Song M, et al. Impact of a disease-management program on symptom burden and health-related quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and their care partners. Heart Lung J Acute Crit Care. 2010;39(4):302–313. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belkin A, Albright K, Swigris JJ. Interstitial lung disease – original article: a qualitative study of informal caregivers’ perspectives on the effects of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMJ Open Resp Res. 2014:1. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2013-000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rocker G, Simpson AC, Horton R. Palliative care in advanced lung disease: the challenge of integrating palliation into everyday care. Chest. 2015;148(3):801–809. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown C, Jecker NS, Curtis JR. Inadequate palliative care in chronic lung disease. AnnalsATS. 2016;13(3):311–316. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201510-666PS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beernaert K, Cohen J, Deliens L, et al. Referral to palliative care in COPD and other chronic diseases: a population-based study. Respir Med. 2013;107(11):1731–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown CE, Engelberg RA, Nielsen EL, Curtis JR. Palliative care for patients dying in the ICU with chronic lung disease compared to metastatic cancer. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(5) doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201510-667OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindell K, Liang Z, Hoffman L, et al. Palliative care and location of death in decedents with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2015;147(2):423–429. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bajwah S, Higginson IJ, Ross JR, et al. The palliative care needs for fibrotic interstitial lung disease: a qualitative study of patients, informal caregivers and health professionals. Palliat Med. 2013;27(9):869–876. doi: 10.1177/0269216313497226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wijsenbeek M, Erasmus MC, Bendstrup E, Ross J, Wells A. Cultural difference in palliative care in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2015;148(2) doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swigris JJ, Stewart AL, Gould MK, Wilson SR. Patients’ perspectives on how idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis affects the quality of their lives. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:61. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bajwah S, Higginson IJ, Ross JR, et al. Specialist palliative care is more than drugs: a retrospective study of ILD patients. Lung. 2012;190(2):215–220. doi: 10.1007/s00408-011-9355-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bajwah S, Koffman J, Higginson IJ, et al. “I wish i knew more…” the end-of-life planning and information needs for end-stage fibrotic interstitial lung disease: views of patients, carers, and health professionals. BMJ. 2013;3(1):84–90. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyatzis R. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.RAK . Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duck A, Spencer LG, Bailey S, Leonard C, Ormes J, Caress AL. Perceptions, experiences and needs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(5) doi: 10.1111/jan.12587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swigris JJ, Kuschner WG, Kelsey JL, Gould MK. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: challenges and opportunities for the clinician and investigator. Chest. 2005;127(1):275–283. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richeldi L. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: moving forward. BMC Med. 2015;13(231) doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0481-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King T, Jr, Tooze JA, Schwarz MI, Brown KR, Cherniack RM. Predicting survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: scoring system and survival model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1171–1181. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.7.2003140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamas DJ, Kawut SM, Bagiella E, et al. Delayed access and survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(7):842–847. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0668OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sampson C, Gill B, Harrison NK, Nelson A, Byrne A. The care needs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and their carers (CaNoPy): results of a qualitative study. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15(155) doi: 10.1186/s12890-015-0145-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egan JJ. Follow-up and nonpharmacological management of the idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patient. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20(120):114–117. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00001811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JS, McLaughlin S, Collard HR. Comprehensive care of the patient with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17(5):348–354. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328349721b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belkin A, Swigris J. Pulmonary fibrosis – original article: a qualitative study of informal caregivers’ perspectives on the effects of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMJ Open Resp Res. 2014 doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2013-000007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2013-000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Bajwah S, Ross JR, Wells AU, et al. Palliative care for patients with advanced fibrotic lung disease: a randomised controlled phase II and feasibility trial of a community case conference intervention. Thorax. 2015;70:830–839. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moua T, Westerly BD, Dulohery MM, Daniels CE, Ryu JH, Lim KG. Patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease hospitalized for acute respiratory worsening: a large cohort analysis. Chest. 2015;149(5) doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mallick S. Outcome of patients admitted to intensive care unit with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Resp Med. 2008;102:1355–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holland A, Fiore JF, Goh N, et al. Be honest and help me prepare for the future: what people with interstitial lung disease want from education in pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis. 2015;12(2):93–101. doi: 10.1177/1479972315571925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curtis J, Engelberg R, Young RP, et al. An approach to understand the interaction of hope and desire for explicit prognostic information among individuals with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:610–620. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blackhall L, Read P, Stukenborg G, et al. Care track for advanced cancer: impact and timing of an outpatient palliative care clinic. J Palliat Med. 2015;19(1) doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scibetta C, Kerr K, Mcguire J, Rabow MW. The costs of waiting implications of the timing of palliative care consultation among a cohort of decedents at a comprehensive care center. J Palliat Med. 2015;19(1) doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maciasz RM, Arnold RM, Chu E, et al. Does it matter what you call it? A randomized trial of language used to describe palliative care services. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:3411–3419. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1919-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]